11 Markets and consumer demand

MIFIRA Framework

Lecture 11

Markets and consumer demand

Chris Barrett and Erin Lentz

February 2012

Households and Consumption: Analysis of Demand

• Household consumption choices

– Access: How do households interact with markets?

– Preferences: Which transfer(s) do households prefer?

– Terms of trade (ToT)

– Elasticities

– Marginal propensities to consume (MPC)

– Commodities: Which commodities to analyze?

2

Q1. Are local markets functioning well?

• 1a. Are food insecure households well connected to local markets?

• 1b. How will local demand respond to transfers?

• 1e. Do food insecure households have a preference over the form/mix of aid they receive?

• 2b. Will agency purchases drive up food prices excessively in source markets?

3

Access

• Basic info: which markets, for what products, when?

• What constrains access?

– Community-level market access and inter-community constraints

• Distance, safety, costs, seasons

– Intra-community constraints

• Socio-cultural reasons (gender, caste, marital status, etc.), safety, OVCs, HIV+ households

• When are access constraints insurmountable?

4

Community-level access questions

• What types of markets can community members access?

– Are any markets currently inaccessible?

– Does this vary with seasons?

• How far away are the markets?

– Can households travel to a larger market if local market prices increase too much?

• Are there key products not locally produced unavailable in the market?

– Does this appear to be due to commercial supply disruptions, government trade bans, high prices, insufficient local demand, or some other reason? 5

Intra-community market access questions

• Does everyone within a community have equal access to local markets?

– How does market access differ for likely targeted recipients?

– How do households with limited access cope?

– Which household members use markets?

– Do households use cash, credit, or barter?

• What staples and substitutes do target populations buy from local markets?

6

Methods of understanding access

• Information sources:

– Expenditure data

– Rapid Appraisal

– Key Informants

– Household survey

– Focus group discussions

• by gender

• by target population

– Optimal ignorance, i.e., the fine art of asking questions

• Innovative delivery mechanisms may alleviate identified constraints

7

Preferences

• Eliciting preferences can identify not only preferred transfer but also issues and concerns of households or individuals

• When eliciting preferences, need to provide information on how transfers would most likely be delivered

• Will delivery location and timing for different transfers differ?

• Will cash transfers be inflation indexed?

• What shapes preferences?

8

Preferences

• Preferences across households may vary

– Income levels and sources, labor availability, frequency of market access…

• Preferences within households may vary

– Gender, age, resource control, labor availability…

• Preferences drive elasticities

9

Eliciting preferences

• Preferences can be sensitive: who is asked and where can shape findings

Source: Lentz (2009)

10

Income and Food Consumption

• Engel ’ s Law

– As income increases, the proportion of the budget spent on food decreases

– Poor households spend proportionally more on food than richer households

• Bennett ’ s Law

– As income increases, the proportion of the budget spent on ‘ starchy-staples ’ decreases

• Reflects desire for dietary diversity

• Sharper than Engel ’ s Law

• Price increases of starchy staples are most burdensome to poor households

11

Measures of Food Consumption

Relative to Household Income Level

(in Log form)

Source: Timmer et al. (1983). p. 57 12

Income and Consumption

• Normal goods

– Change in income changes demand for the normal good in the same direction.

– Income effect and substitution effect work in the same direction (combining effects)

– When the price of a normal good rises, households may substitute other goods for it.

13

Income and Consumption

• Inferior goods

– Increase in income results in a decrease in demand

– Income effect is in the opposite direction from the substitution effect (countervailing effects)

– For very poor households, demand for an inferior good can increase when prices rise (and no substitutes are available) or when income falls

• Households can no longer afford to buy more expensive foods and thus spend more on cheaper, lower quality calorie sources

14

Effects of a Food Price Increase

• All else equal, price increases for inferior goods with few substitutes harm consumers ’ welfare more than equivalent price increases for substitutable or normal goods

15

Income and Substitution Effects due to a Price Increase

16

Source: Timmer et al. 1983. P. 44.

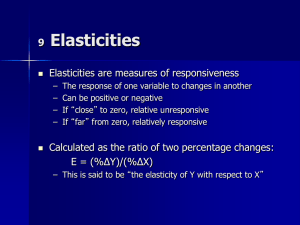

Elasticities

• General formula for elasticities: e ij

= (Percentage change in variable i) / (Percentage change in variable j)

• Own price elasticity e

0wn price

= Quantity 1 % change / Price % change in quantity 1

• Income elasticity e i

= % change in demand for variable i / % change in income

• Cross price elasticity

17

Elasticity of demand (FEWs, Lesson 1, p. 22)

18

What makes supply or demand elastic?

(FEWs, Lesson 1, p. 24)

19

What makes supply or demand elastic?

(FEWs, Lesson 1, p. 24)

20

Income and price elasticity for the bread and cereals food group by per capita GDP

Source: Sited in World Food Programme, (2008) “PDPE Market Analysis Tool: Price and income elasticities” p.6: USDA-ESR elasticities database, 1996, and GDP data from WDI 2006.

Note: Income and price elasticity estimates for the cereal and bread food groups are extracted from the USDA-ESR database collected in 1996. GDP/capita values are in constant 2000 USD for the year 2004. These values were extracted from the WDI 2006 database.

The number of countries for which data was available is 107.

21

Income elasticities

• Income elasticity of demand

– Another definition of Engels Law: the income elasticity of demand is less than one.

• Income elasticity of demand is closer to 1 for poorer households than for richer households

• Income elasticity of demand

• e i

= Percentage increase in demand expenditure / Percentage increase in income

• generally lies between 0 and 1

22

Example: Income Elasticity of Demand: Estimating increased volume demanded for food due to cash distribution

Source: Barrett et al. 2009

23

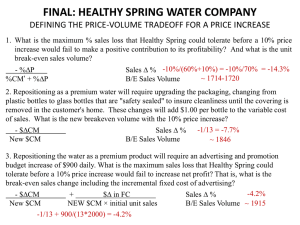

Price Elasticities

• A 1% increase in prices changes demand by x% e

0wn price

= % change in demand for Good A / % change in Price of Good A

• Price elasticities are generally below zero but for poor households and staple products, price elasticities may be above zero…why?

24

Price elasticities

• Use price elasticities to understand the affect of increasing prices on consumers ’ demand

• Also, use price elasticities to estimate the affect of increased food supply on prices

• Example: food aid increases supply by 1%

– Price elasticity = -0.2 implies food price falls by 5%:

(1%/ x% = -0.2)

– Price elasticity = -0.6 implies food price falls by

1.7%: ( 1% / x%= -0.6)

25

Using Elasticities: Inverse Price Elasticity of Demand:

Estimating % Change in Price due to a % Change in

Supply: High Estimate

Price elasticity of demand: Less elastic (closer to zero)

Inverse price elasticity of Demand: High estimate

Estimate food aid delivery volume (i.e., addition to local supply)

Estimated market supply pre-delivery

% Supply Expansion due to Food Aid Deliveries

Estimated Percentage change in prices: High estimate

Source: Barrett et al. 2009

-0.25

-4.00

25.00

500.00

0.05

-20.00% price elasticity = percent change in supply / percent change in price x=change in price

-0.25=0.05%/x, x = -20%

26

Using Elasticities: Inverse Price Elasticity of Demand:

Estimating % Change in Price due to a % Change in

Supply: Low Estimate

Price elasticity of demand: More elastic (further from zero)

Inverse price elasticity of Demand: Low estimate

Estimate food aid delivery volume (i.e., addition to local supply)

Estimated market supply pre-delivery

% Supply Expansion due to Food Aid Deliveries

Estimated Percentage change in prices: Low estimate

Source: Barrett et al. 2009

-0.80

-1.25

25.00

500.00

0.05

-6.25% price elasticity = percent change in supply / percent change in price

-1.25=0.05%/x, x = -6.25%

27

Limitations of Elasticities

• Rare to find elasticities for the populations of interest

– Try to find urban / rural and poor/non-poor

• Rare to find elasticities for the commodities of interest

– Use sub-group

• Always compute high / low estimates and be conservative

• Elasticities incorporate substitution effects between foods, but not other second-round coping mechanisms

28

Marginal Propensity to Consume

• As income increases by an amount, what is the amount that demand increase?

MPC = Change in consumption / Change in income

• Consider estimating an MPC in the field

– Where income elasticities are unavailable or unreliable

– Verify estimates

29

Computing MPCs in the field

• Ask likely recipient households how they would spend a one-time gift.

• Using proportional piling, households indicate what proportion of this gift would be spent on food (or for key each commodity).

• The denominator is the size of the one-time gift

• The numerator is the value of the gift that would be spent on a certain commodity.

MPC = Expenditure on good_1/ Value of transfer

30

Terms of Trade

• Terms of trade for good i and j is the ratio of prices for goods i and j.

ToT ij

= (Price of good i)/(Price of good j)

• Compute for target groups:

ToTwr*= (day wages) / (price of 1 kg of rice)

*Sometime called the “ net barter terms of trade ”

31

Terms of Trade

1. Who are the target groups or livelihood groups of interest?

2. What is/are the main cash income sources of these groups, such as the sale of a cash crop, livestock or daily labour?

3. What is/are the main staple foods consumed by these groups?

4. Which data is required and/or available?

Source: WFP PDPE

32

Terms of Trade: Guinea Bissau

WFP 2008. “ PDPE Market Analysis Tool: Terms of Trade ” p. 6.

33

Terms of Trade: Limitations

• Diverse livelihoods

• Diverse consumables

• Substitution effects

• Dynamic

• Local price data may differ from national data

34

Commodity Choice

• Choose commodities that are:

– Crucial for food security

• staples

• proteins

• fats

• other foods containing key micronutrients (e.g., iron)

– Consumed by the target population

• Assess whether seasonal consumption patterns differ

– Generally available on the market

• For example, corn-soy blend (CSB) is rarely available in large quantity on local markets

– Nutritional assessments may suggest particular products

• Fresh fruit and vegetables in refugee camps

35

Commodity Choice

• Compute budget shares

– Most concerned about commodities whose price changes are most likely to most impact the poor

» Focus on budget shares of the targeted populations

– A budget share is the ratio of the amount spent on one commodity for a given time-period divided by the amount of

(cash and non-cash) budget earned for the same time period

36

Commodity Characteristics

• Assess particularly staples and substitutes, but also key complementary goods and services, such as water, medicine, fuel, or shelter.

• Is each candidate commodity an inferior or normal good?

• What are the substitutes for these goods?

37

Commodity Choice

• The number of commodities to consider will depend on:

– Local consumption patterns

– Nutritional concerns

– Commodity characteristics (e.g., substitutability, dominance in diet)

– Timeliness

– Cost

• Keep in mind:

– Ask each trader about no more than 2-3 commodities (1-1.5 hours max)

– Commodity choice will inform the length of the supply chain (includes source and destination markets)

38