Guidelines for Sighting

advertisement

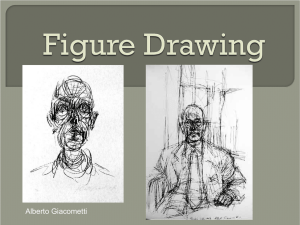

Guidelines for Sighting Drawing or representing a three-dimensional object on a two-dimensional surface requires in essence a language translation. You are translating a three-dimensional form into a language that will be effective on a twodimensional surface….Drawing paper. Some of you may feel like your drawings are much more successful when you draw from a photograph as a reference. That’s because the three-dimensional form has already been translated for you. *** A sighting stick is the basic tool for the process of sighting. A wooden dowel 1/8” in diameter and about 10” to 12” long is best. But whatever you use, it should be slender and straight. A pencil can suffice when nothing else is available. *** All of your sighting observations will take place in an imaginary two-dimensional plane that is parallel to your face. If you look downward, the imaginary plane remains parallel to your face. The same if you look upward. *** Always keep your arm fully extended and lock your elbow when sighting. This keeps a constant scale, which is especially important when you are sighting for relative or comparative proportional relationships. *** Never tip your stick forward or backward, keep it parallel to your face. *** It is helpful to close one eye when sighting. Monocular vs. binocular (flattens what you see). *** When sighting, you must begin by establishing which object or shape will serve as your point of reference or unit of measure. *** When working with the human figure, the head is frequently used as the point of reference. In instances where the head is not visible or is partially obscured, another unit of measure will need to be established ( possibly a hand or foot). Applications of Sighting First Application: Sighting for Relative Proportions Before beginning the actual sighting process, do a delicate gesture drawing based on what you see. This “breaks the ice” of a blank piece of paper and gives a sense of how the objects being referred to will occupy the paper surface. Draw your point of reference first. ** Begin by sighting to establish between the total height and total width of the object (head). ** With arm extended, align the end of the sighting stick on one side of the head and then slide your thumb back until the tip is aligned with the other side. ** With your arm still fully extended, rotate your arm until the stick is in a vertical position and observe how many times the width of the head repeats itself in the height of the head. ** Continue to refer to your point of reference for establishing relative proportions throughout the drawing. Foreshortening Foreshortening can be especially challenging since it is often recorded with a significant amount of inaccuracy and distortion. While sighting is an ideal way to overcome this inaccuracy, there are a few things to be particularly attentive to when dealing with foreshortening. First, be aware of the fact that when foreshortening is evident, the apparent relationship between the length and width of forms is altered to varying degrees, depending upon the severity of the foreshortening. For example, a foreshortened view of the thigh may measure wider from side to side than it does in length from the hip area to the knee area. Second, be on guard against tilting your sighting stick in the direction of the foreshortened axis. Be aware that instances of overlapping, where one part of an object meets another part, are more pronounced and dramatic in a foreshortened view and require greater attention to the interior contours that give definition to this. Second Application: Sighting for Angles and Axis Lines in Relation to Verticals and Horizontals or in Relation to the Face of a Clock An axis line is an imaginary line that runs through the core or center of a form. Some observed angles are more apparent than others. Sighting can be used to provide greater accuracy when drawing obvious or implied angles. Simply align your sighting stick visually along the observed axis of the angle and observe the relationship between the angle and a true vertical or horizontal, whichever it relates to more closely. When drawing the angle maintain the same relationship to the vertical or horizontal that you observed. (The left and right sides of your drawing paper provide fixed verticals for comparison, and the top and bottom of your drawing paper provide fixed horizontals for comparison. Third Application: Sighting for Vertical and/or Horizontal Alignments Between Two or More Landmarks This sighting process is closely related to sighting for angles and axis lines but is used to observe vertical or horizontal alignment that is less apparent or to observe a vertical or horizontal alignment between more distant reference points (landmarks). Keep in mind that the human form is rich in visual landmarks. Many of these landmarks are readily apparent and easily identified verbally ( the tip of the nose, the back of the heel, the tip of the elbow, the wrist bone, the navel, the inside corner of the eye, the right nipple, the side of the face, etc.). Many more landmarks are available to you that may not be as easy to describe. These landmarks may be defined by a significant directional change in a contour, by a point of overlap or intersection, or by the outermost or innermost point of a curve. These alignments help to maintain an accurate relationship of size and placement when drawing the figure and its component parts. Sighting for vertical or horizontal alignments between figurative landmarks that are spaced far apart on the body is especially helpful. For example, you may observe that the left or right side of the face aligns vertically with the foot or ankle area. When you observe a vertical or horizontal alignment between landmarks, it is fairly simple to translate this alignment since a vertical or horizontal is fixed or constant.