Short-Run Conditions and Long

advertisement

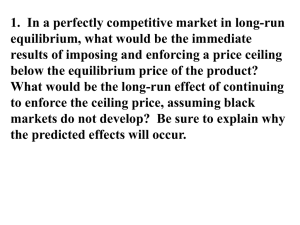

Long-Run Costs and Output Decisions Short-Run Conditions and Long-Run Directions Long-Run Costs: Economies and Diseconomies of Scale Long-Run Adjustments to Short-Run Conditions Output Markets 1 of 36 LONG-RUN COSTS AND OUTPUT DECISIONS We begin our discussion of the long run by looking at firms in three short-run circumstances: (1) firms earning economic profits, (2) firms suffering economic losses but continuing to operate to reduce or minimize those losses, and (3) firms that decide to shut down and bear losses just equal to fixed costs. 2 of 36 SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS AND LONG-RUN DIRECTIONS breaking even The situation in which a firm is earning exactly a normal rate of return. MAXIMIZING PROFITS Example: The Blue Velvet Car Wash TABLE 9.1 Blue Velvet Car Wash Weekly Costs TOTAL VARIABLE COSTS (TVC) (800 WASHES) TOTAL FIXED COSTS (TFC) 1. Normal return to investors 2. Other fixed costs (maintenance contract, insurance, etc.) $ 1,000 1. Labor 2. Materials TOTAL COSTS (TC = TFC + TVC) $ 3,600 $ 1,000 600 Total revenue (TR) at P = $5 (800 x $5) $ 4,000 $ 1,600 Profit (TR - TC) $ 400 1,000 $ 2,000 3 of 36 SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS AND LONG-RUN DIRECTIONS Graphic Presentation FIGURE 9.1 Firm Earning Positive Profits in the Short Run 4 of 36 SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS AND LONG-RUN DIRECTIONS MINIMIZING LOSSES operating profit (or loss) or net operating revenue Total revenue minus total variable cost (TR - TVC). In general, ■ If revenues exceed variable costs, operating profit is positive and can be used to offset fixed costs and reduce losses, and it will pay the firm to keep operating. ■ If revenues are smaller than variable costs, the firm suffers operating losses that push total losses above fixed costs. In this case, the firm can minimize its losses by shutting down. 5 of 36 SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS AND LONG-RUN DIRECTIONS Producing at a Loss to Offset Fixed Costs: The Blue Velvet Revisited TABLE 9.2 A Firm Will Operate If Total Revenue Covers Total Variable Cost CASE 1: SHUT DOWN Total Revenue (q = 0) CASE 2: OPERATE AT PRICE = $3 $ 0 Total Revenue ($3 x 800) Fixed costs Variable costs Total costs $ 2,000 + 0 $ 2,000 Fixed costs Variable costs Total costs Profit/loss (TR - TC) - $ 2,000 Operating profit/loss (TR - TVC) Total profit/loss (TR - TC) $ 2,400 $ 2,000 + 1,600 $ 3,600 $ 800 - $ 1,200 6 of 36 SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS AND LONG-RUN DIRECTIONS Graphic Presentation FIGURE 9.2 Firm Suffering Losses but Showing an Operating Profit in the Short Run 7 of 36 SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS AND LONG-RUN DIRECTIONS Remember that average total cost is equal to average fixed cost plus average variable cost. This means that at every level of output, average fixed cost is the difference between average total and average variable cost: ATC = AFC + AVC or AFC = ATC - AVC = $4.10 - $3.10 = $1.00 As long as price (which is equal to average revenue per unit) is sufficient to cover average variable costs, the firm stands to gain by operating instead of shutting down. 8 of 36 SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS AND LONG-RUN DIRECTIONS Shutting Down to Minimize Loss TABLE 9.3 A Firm Will Shut Down If Total Revenue Is Less Than Total Variable Cost CASE 1: SHUT DOWN Total Revenue (q = 0) CASE 2: OPERATE AT PRICE = $1.50 $ 0 Total revenue ($1.50 x 800) $ 1,200 Fixed costs Variable costs Total costs $ 2,000 + 0 $ 2,000 Fixed costs Variable costs Total costs $ 2,000 + 1,600 $ 3,600 Profit/loss (TR - TC): - $ 2,000 Operating profit/loss (TR - TVC) Total profit/loss (TR - TC) - $ 400 - $ 2,400 Any time that price (average revenue) is below the minimum point on the average variable cost curve, total revenue will be less than total variable cost, and operating profit will be negative—that is, there will be a loss on operation. In other words, when price is below all points on the average variable cost curve, the firm will suffer operating losses at any possible output level the firm could choose. When this is the case, the firm will stop producing and bear losses equal to fixed costs. This is why the bottom of the average variable cost curve is called the shut-down point. At all prices above it, the marginal cost curve shows the profitmaximizing level of output. At all prices below it, optimal short-run output is zero. 9 of 36 SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS AND LONG-RUN DIRECTIONS shut-down point The lowest point on the average variable cost curve. When price falls below the minimum point on AVC, total revenue is insufficient to cover variable costs and the firm will shut down and bear losses equal to fixed costs. The short-run supply curve of a competitive firm is that portion of its marginal cost curve that lies above its average variable cost curve (Figure 9.3). 10 of 36 SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS AND LONG-RUN DIRECTIONS FIGURE 9.3 Short-Run Supply Curve of a Perfectly Competitive Firm 11 of 36 SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS AND LONG-RUN DIRECTIONS THE SHORT-RUN INDUSTRY SUPPLY CURVE short-run industry supply curve The sum of the marginal cost curves (above AVC) of all the firms in an industry. FIGURE 9.4 The Industry Supply Curve in the Short Run Is the Horizontal Sum of the Marginal Cost Curves (above AVC) of All the Firms in an Industry 12 of 36 SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS AND LONG-RUN DIRECTIONS LONG-RUN DIRECTIONS: A REVIEW TABLE 9.4 Profits, Losses, and Perfectly Competitive Firm Decisions in the Long and Short Run SHORT-RUN CONDITION Profits Losses TR > TC 1. With operating profit (TR TVC) 2. With operating losses (TR < TVC) SHORT-RUN DECISION LONG-RUN DECISION P = MC: operate Expand: new firms enter P = MC: operate Contract: firms exit (losses < fixed costs) Shut down: Contract: firms exit losses = fixed costs 13 of 36 LONG-RUN COSTS: ECONOMIES AND DISECONOMIES OF SCALE increasing returns to scale, or economies of scale An increase in a firm’s scale of production leads to lower costs per unit produced. constant returns to scale An increase in a firm’s scale of production has no effect on costs per unit produced. decreasing returns to scale, or diseconomies of scale An increase in a firm’s scale of production leads to higher costs per unit produced. 14 of 36 LONG-RUN COSTS: ECONOMIES AND DISECONOMIES OF SCALE INCREASING RETURNS TO SCALE The Sources of Economies of Scale Most of the economies of scale that immediately come to mind are technological in nature. Some economies of scale result not from technology but from sheer size. 15 of 36 LONG-RUN COSTS: ECONOMIES AND DISECONOMIES OF SCALE Example: Economies of Scale in Egg Production TABLE 9.5 Weekly Costs Showing Economies of Scale in Egg Production JONES FARM 15 hours of labor (implicit value $8 per hour) Feed, other variable costs Transport costs Land and capital costs attributable to egg production Total output Average cost CHICKEN LITTLE EGG FARMS INC. Labor Feed, other variable costs Transport costs Land and capital costs Total output Average cost TOTAL WEEKLY COSTS $120 25 15 17 $177 2,400 eggs $.074 per egg TOTAL WEEKLY COSTS $ 5,128 4,115 2,431 19,230 $30,904 1,600,000 eggs $.019 per egg 16 of 36 LONG-RUN COSTS: ECONOMIES AND DISECONOMIES OF SCALE Graphic Presentation long-run average cost curve (LRAC) A graph that shows the different scales on which a firm can choose to operate in the long run. 17 of 36 LONG-RUN COSTS: ECONOMIES AND DISECONOMIES OF SCALE FIGURE 9.5 A Firm Exhibiting Economies of Scale 18 of 36 LONG-RUN COSTS: ECONOMIES AND DISECONOMIES OF SCALE CONSTANT RETURNS TO SCALE Technically, the term constant returns means that the quantitative relationship between input and output stays constant, or the same, when output is increased. Constant returns to scale mean that the firm’s long-run average cost curve remains flat. 19 of 36 LONG-RUN COSTS: ECONOMIES AND DISECONOMIES OF SCALE DECREASING RETURNS TO SCALE FIGURE 9.6 A Firm Exhibiting Economies and Diseconomies of Scale All short-run average cost curves are U-shaped, because we assume a fixed scale of plant that constrains production and drives marginal cost upward as a result of diminishing returns. In the long run, we make no such assumption; instead, we assume that scale of plant can be changed. 20 of 36 LONG-RUN COSTS: ECONOMIES AND DISECONOMIES OF SCALE It is important to note that economic efficiency requires taking advantage of economies of scale (if they exist) and avoiding diseconomies of scale. optimal scale of plant The scale of plant that minimizes average cost. 21 of 36 LONG-RUN ADJUSTMENTS TO SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS SHORT-RUN PROFITS: EXPANSION TO EQUILIBRIUM FIGURE 9.7 Firms Expand in the Long Run When Increasing Returns to Scale Are Available 22 of 36 LONG-RUN ADJUSTMENTS TO SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS Firms will continue to expand as long as there are economies of scale to be realized, and new firms will continue to enter as long as positive profits are being earned. In the long run, equilibrium price (P*) is equal to long-run average cost, short-run marginal cost, and short-run average cost. Profits are driven to zero: P* = SRMC = SRAC = LRAC where SRMC denotes short-run marginal cost, SRAC denotes shortrun average cost, and LRAC denotes long-run average cost. No other price is an equilibrium price. Any price above P* means that there are profits to be made in the industry, and new firms will continue to enter. Any price below P* means that firms are suffering losses, and firms will exit the industry. Only at P* will profits be just equal to zero, and only at P* will the industry be in equilibrium. 23 of 36 LONG-RUN ADJUSTMENTS TO SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS SHORT-RUN LOSSES: CONTRACTION TO EQUILIBRIUM FIGURE 9.8 Long-Run Contraction and Exit in an Industry Suffering Short-Run Losses 24 of 36 LONG-RUN ADJUSTMENTS TO SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS As long as losses are being sustained in an industry, firms will shut down and leave the industry, thus reducing supply—shifting the supply curve to the left. As this happens, price rises. This gradual price rise reduces losses for firms remaining in the industry until those losses are ultimately eliminated. Whether we begin with an industry in which firms are earning profits or suffering losses, the final long-run competitive equilibrium condition is the same: P* = SRMC = SRAC = LRAC and profits are zero. At this point, individual firms are operating at the most efficient scale of plant—that is, at the minimum point on their LRAC curve. 25 of 36 LONG-RUN ADJUSTMENTS TO SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS THE LONG-RUN ADJUSTMENT MECHANISM: INVESTMENT FLOWS TOWARD PROFIT OPPORTUNITIES In efficient markets, investment capital flows toward profit opportunities. The actual process is complex and varies from industry to industry. When firms in an industry are making positive profits, capital is likely to flow into that industry. Entrepreneurs start new firms, and firms producing entirely different products may join the competition. 26 of 36 LONG-RUN ADJUSTMENTS TO SHORT-RUN CONDITIONS long-run competitive equilibrium When P = SRMC = SRAC = LRAC and profits are zero. Investment—in the form of new firms and expanding old firms—will over time tend to favor those industries in which profits are being made, and over time industries in which firms are suffering losses will gradually contract from disinvestment. 27 of 36 OUTPUT MARKETS: A FINAL WORD In the last four chapters, we have been building a model of a simple market system under the assumption of perfect competition. You have now seen what lies behind the demand curves and supply curves in competitive output markets. The next two chapters take up competitive input markets and complete the picture. 28 of 36 REVIEW TERMS AND CONCEPTS breaking even constant returns to scale decreasing returns to scale, or diseconomies of scale increasing returns to scale, or economies of scale long-run average cost curve (LRAC) long-run competitive equilibrium operating profit (or loss) or net operating revenue optimal scale of plant short-run industry supply curve shut-down point long-run competitive equilibrium, P = SRMC = SRAC = LRAC 29 of 36 Appendix EXTERNAL ECONOMIES AND DISECONOMIES AND THE LONG-RUN INDUSTRY SUPPLY CURVE When long-run average costs decrease as a result of industry growth, we say that there are external economies. When average costs increase as a result of industry growth, we say that there are external diseconomies. 30 of 36 Appendix TABLE 9A.1 Construction of New Housing and Construction Materials Costs, 2000–2005 CONSTRUCTION HOUSING MATERALS CONSUMER STARTS PRICES PRICES HOUSE PRICES % CHANGE % CHANGE % CHANGE OVER THE OVER THE OVER THE %D OVER THE PREVIOUS HOUSING PREVIOUS PREVIOUS PREVIOUS YEAR YEAR STARTS YEAR YEAR YEAR - 2000 1573 - - - 2001 7.5 8.2 1661 5.6% 0% 2.8% 2002 7.5 6.6 1710 2.9% 1.5% 1.5% 2003 7.9 6.4 1853 8.4% 1.6% 2.3% 2004 12.0 1949 5.2% 8.3% 2.7% 2005 13.4 2053 5.3% 5.4% 2.5% 31 of 36 Appendix THE LONG-RUN INDUSTRY SUPPLY CURVE FIGURE 9A.1 A Decreasing-Cost Industry: External Economies 32 of 36 Appendix long-run industry supply curve (LRIS) A graph that traces out price and total output over time as an industry expands. decreasing-cost industry An industry that realizes external economies—that is, average costs decrease as the industry grows. The long-run supply curve for such an industry has a negative slope. 33 of 36 Appendix FIGURE 9A.2 An Increasing-Cost Industry: External Diseconomies 34 of 36 Appendix increasing-cost industry An industry that encounters external diseconomies— that is, average costs increase as the industry grows. The long-run supply curve for such an industry has a positive slope. constant-cost industry An industry that shows no economies or diseconomies of scale as the industry grows. Such industries have flat, or horizontal, long-run supply curves. 35 of 36