The Theory of Production

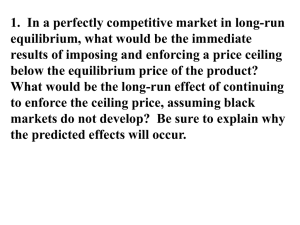

advertisement

The Theory of Production Production in the Long Run (LR) 1 Lesson Objectives • Understand the theory that explains the short run • Appreciate that different sized firms have different levels of productive efficiency • Understand the theory of long-run costs • Appreciate the relationship between the short run and the long run 2 Connector What might the following terms mean? • • • • • • • • • • Total costs Fixed costs Variable costs Short run Long run Marginal Product Average product Increasing marginal returns Diminishing marginal returns Law of diminishing marginal returns • • • • • • • • Optimum output Productive efficiency Depreciation Semi-variable costs Average fixed cost Average variable cost Average total cost Marginal cost 3 The Big Picture • We will look at the costs of production faced by the individual firm and we will analyse them in more depth than you experienced at AS. • We will look at marginal and average costs and revenues and use numerical examples to explain firms’ behaviour. • You will become aware of the diagrammatic presentation of costs curves which we use at A2 and the effect of time on the firms’ costs in terms of short-run and long-run behaviour. 4 Big Picture • To arrive at the learning outcomes you will do the following: • Listen to teacher demonstrations on PPP • Draw graphs • Watch VIDEO • ‘Stretch and challenge’ Questions • Group work • Independent work • Class discussion • Debate economic issues • Short presentation • Demonstration on the board • Pair marking • Advise on examiner’s tip 5 Lesson Outcome • Understand the difference between the short and long run and the theories that underpin them • Be able to use short-run (SR) and long-run (LR) concepts to answer questions • Be able to explain the relationship between average and marginal costs both in words and graphically • Understand the importance of firms achieving the minimum efficient scale and what it implies. 6 Key Terms • • • • • • Increasing returns to scale Decreasing returns to scale Constant returns to scale Minimum efficient scale Economies of scale Diseconomies of scale 7 Production in the Long Run (LR) 8 Production in the Long Run (LR) • In the LR the firm can temporarily overcome the problem of diminishing returns as it can vary its fixed factors. • In the case of the furniture manufacturer it could move to larger premises. • But the problem of diminishing returns re-emerges as soon as the fixed factor becomes overloaded, and though specialisation can delay diminishing returns setting in, they will eventually reappear as the firm increases output beyond optimal output – the ideal combination of fixed and variable factors • The furniture manufacturer could move to larger premises.9 Production in the Long Run (LR) • In Table 1.1 the ATC per unit is at its lowest at 6 workers where 60 units are produced (ATC must be at its lowest point as the average product is at its maximum). • If the firm wants to produce 63 units without diminishing returns setting in, it will need a different combination of fixed and variable factors and this will be true of all different levels of output. • This can be shown in Figure 1.5 where there is a separate short-run ATC curve for every level of output. 10 11 12 Production in the Long Run (LR) • The firm producing the output 0A is producing at the lowest point on the curve labelled ATC, • While the firm with the higher level of output faces a cost structure which is shown by curve ATC3. • Each short-run average total cost (SRATC) represents the particular short-run size or the scale of the firm • And we assume that increasing returns to scale are taking place as the trend of the costs is downwards as output increases. 13 Production in the Long Run (LR) • We have seen that in the SR the firm’s productively efficient level occurs at the lowest point of the ATC curve. • In the LR we assume that firms can vary the scale of production and that it can vary all its factors of production. • In the LR the furniture manufacturer will be able to increase the size of, or move to, larger premises and employ more capital equipment. • Thus in the LR there are no fixed factors and we expect that increasing size will lead to economies of scale. • The LR ATC curve is constructed from the optimum output levels of the SR curves as shown in Figure 1.7. 14 15 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p cNtFWuw78Q 16 Production in the Long Run (LR) • Figure 1.7 shows that the long-run average total cost (LRATC) facing the firm • And we assume that as the firm’s scale of operations increases it will face falling costs as it receives increasing returns to scale. • The LRATC reflects that due to economies of scale as an increase in factor inputs will result in a more than proportionate increase in output. • However, this can only continue up to a certain level of output and then diseconomies of scale set in. • This can be illustrated in Table 1.4 below: 17 Production in the Long Run (LR) • Table 1.4 shows that the change in total output increases by a greater percentage as the firm increases its scale of production in years 1 to 3. • The firm is experiencing increasing returns to scale and so its average cost per unit falls, indicating economies of scale. 18 Production in the Long Run (LR) • In years 3 and 4 output rise by the same percentage when inputs rise from 150 to 200. • The firm has experienced constant returns to scale and average costs remain unchanged. • In year 5, output rises by a smaller percentage than inputs and the firm experiences decreasing returns to scale and the average cost per unit increases, which indicates diseconomies of scale. • These differing returns to scale are shown in Figures 1.7 and 1.8. 19 Production in the Long Run (LR) These differing returns to scale are shown in Figures 1.7 and 1.8 • Both diagrams show a situation where unit costs fall as output increases and the firm receives increasing returns to scale. • But beyond a certain level of output costs begin to increase and the firm suffers decreasing returns to scale. • Both diagrams tend to be stylised as different industries will have different cost structures. • In some, all economies of scale will be reached very quickly, while in others the level of output required to exploit all available economies 20 of scale may be huge. Production in the Long Run (LR) These differing returns to scale are shown in Figures 1.7 and 1.8 • In the left diagram, cost savings are exhausted quickly and unit costs rise rapidly after a certain level of output. • Firms in this industry do not have a great deal of choice about their level of output and are likely to be of similar size. • All Economies of scale will be reached very quickly. 21 Production in the Long Run (LR) These differing returns to scale are shown in Figures 1.7 and 1.8 • • • • • • The right diagram shows another possible shape of the LRATC. Over the range of output 0 to A the LRATC falls and the firm receives increasing returns to scale. Over the range of output A to B, the curve is flat, and the firm experiences constant returns to scale. When output exceeds 0B decreasing returns to scale sets in. Firms in this industry are likely to be of different sizes as once they have reached 0A they may have the opportunity to be able to produce thousands more units of output before decreasing returns to scale set in at B. 22 This flat part of the curve shows constant returns to scale. Production in the Long Run (LR) These differing returns to scale are shown in Figures 1.7 and 1.8 • The optimum level of LR production for a firm occurs at the point of productive efficiency – at the lowest part of the LRATC. • If the LRATC is saucer shaped, as in right diagram, this will occur at the bottom of the curve, between A and B, 23 where constant returns to scale exist. Production in the Long Run (LR) These differing returns to scale are shown in Figures 1.7 and 1.8 • Both diagrams also indicate diseconomies of scale where a less than proportionate increase in output occurs as a result of factor inputs. • The LRATC shows the cheapest possible cost of producing any level of output. 24 Returns to Scale in Long run Production • Increasing returns to scale – When the % change in output > % change in inputs – E.g. a 30% rise in factor inputs leads to a 50% rise in output – Long run average cost will be falling 25 Returns to Scale in Long run Production • Decreasing returns to scale – When the % change in output < % change in inputs – E.g when a 60% rise in factor inputs raises output by only 20% – Long run average cost will be rising 26 Returns to Scale in Long run Production • Constant returns to scale – When the % change in output = % change in inputs – E.g when a 10% increase in all factor inputs leads to a 10% rise in total output – Long run average cost will be constant 27 28 Case Study – page 11 The new face of hunger 29 30 31 Production in the Long Run (LR) The Minimum Efficient Scale • In Figure 1.9 at output OA the firm has grown large enough to have exploited benefits of the internal economics of scale – it has reached the minimum efficient scale (MES). • This corresponds to the lower point of the LRATC curve and it also known as the output of long-run productive efficiency. • While the minimum efficient scale is defined to be the first, lower point on the LRATC, – in reality there is unlikely to be a single level of output; rather there will a range of output, as indicated in the figure 1.9 between OA and OB, where costs are minimised. • Firms are unable to reach the minimum efficient scale are unlikely to be competitive with other firm. • If is produces an output below OA its unit costs will increase and render it uncompetitive with larger firms whose unit costs are lower as they have reached the MES. 32 Production in the Long Run (LR) The Minimum Efficient Scale • The output required to reach the MES will depend on the nature of the industry and its costs structure, and when fixed costs are extremely large compared to variable costs, expanding output will lead to decreasing average costs. • The relationship between the MES and the size of the domestic market may mean that an economy may only be able to support one firm in the industry if the MES is to be achieved. • A domestic firm wanting to reach the MES with only a small home market may need to export its products to increase the size of the potential market and the authorities may have to accept that a monopolistic structure is likely to be the most efficient. 33 34 Answers 1&2 • The minimum efficient scale varies between different industries because different industries have different levels of fixed costs. For example, a company providing rail network services (such as Network Rail) has very high fixed costs, and therefore the minimum efficient scale is only achieved at a very high level of output. Some companies, such as a local bakery, have fairly low fixed costs (but high variable costs) and therefore the minimum efficient scale is low. 35 36 Case Study – page 13 No economies of scale for Proton without global partner 37 38 39 Production in the Long Run (LR) Relationship between short-run & Long-run costs • • • • In Figure 1.7 we saw that any firm that is producing at the lowest point of the SRATC curve is on its LRATC and as its scale of production increases its unit costs are likely to fall. In Figure 1.10 a firm is producing at OA where it is at the lowest point of its shortrun cost curve. If the firm decide to increase its output rapidly to OB, perhaps in response to an unexpected order, its unit costs will increase up the SRATC as it overworks its fixed factors and depart from the optimum factor combination. If the firm decides to increase its scale of production then, as the fixed factors increase and are brought in to use, the firm moves down SRATC1 until it reaches the LRATC at the output OB where once again it has achieved the optimum factor combination and productive efficiency. However some firm, typically smaller ones, may decide that expansion is not an option and will remain at their size and overwork their fixed factors. This may be for reason such as a lack of available finance, little likelihood of a planning application being granted, or fears that market growth may 40 be temporary. Such firms are not reducing their costs to the lowest but may ignore this fact as long as profits are adequate. 41 42 Answers 1. In the short-run, firms will produce more in order to meet growing demand by simply employing more workers. If they employ many more workers, then their short-run average total costs could begin to rise. 43 Answers 2. To tackle the problem, the firm could increase the amount of capital i.e. increase its scale of production. This would cause the entire SRATC curve to shift down and to the right, reaching SRATC1. 44 Answers 3. There are a number of reasons why a firm may not choose to do this. Firstly, the increase in demand may be temporary (e.g. demand for Christmas wrapping paper in December) so if the amount of capital was increased, it wouldn’t be used in the future. Secondly, firms need funds, either from profit or from borrowed money, in order to pay for the investment; many small firms don’t have this option or don’t want to pay high interest rates on loans. 45 Activity 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 AQA Examination-style questions Data response question 1: a) Average costs of generating electricity by nuclear methods have been lower. Fixed costs associated with nuclear are high. External costs associated with nuclear are generally lower. Data shows nuclear power costs 3.2euros per kWh, compared to an average cost for gas of 3.65 and coal of 4.19. b) Define minimum efficient scale. Show MES on a diagram. Firms benefit from producing at the MES because lower costs are likely to lead to higher profits. Consumers may benefit because lower costs often translate into lower prices, thus increasing consumer surplus. Firms need to ensure however that they don’t surpass the MES, and end up with rising LRATC. Additionally, consumers may not benefit if firms don’t pass on the cost reductions in terms of lower prices. 57 AQA Examination-style questions Data response question 1: c) Define diminishing returns. Explain what is meant by the short-run. Explain that diminishing returns are caused by increasing the level of output by using more labour, whilst maintaining other fixed factors of production; thus in the short-run diminishing returns are not eliminated by increasing output. Use LRATC/SRATC envelope curve. Explain what is meant by the long-run. Explain how firms can eliminate diminishing returns by increasing the scale of production in order to increase output i.e. increasing the amount of capital, and not just increasing the amount of labour. Comment that increasing capital is not necessarily easy, owing to finance constraints, planning permissions, legal barriers (e.g. prevention of monopoly power, patents etc) and so firms cannot guarantee that they can eliminate diminishing returns. 58 AQA Examination-style questions Essay question 2: a) Define total costs (i.e. fixed plus variable). Factors affecting fixed costs could include: salary demands of permanent employees (e.g. public sector workers demanding wage increases in line with inflation), rent prices (dependent on area of country etc). Factors affecting variable costs could be: price of fuel (more expensive in winter as demand increases, more expensive if there’s uncertainty in the Middle East etc), changes to the National Minimum Wage affecting non-salaried employees, cost of raw materials (e.g. price of gelatine 59 increased following BSE outbreaks). AQA Examination-style questions Essay question 2: b) Explain what is meant by average cost (use diagram). Reasons for firms having similar costs: often face the same changes in variable costs (i.e. they buy the same raw materials); we might expect production to take place in similarly-sized industrial units. Reasons why they might not face similar costs: products are often differentiated (e.g. costs will be very different for a small company making small batches of cars compared to say, Ford, or boutique chocolate shops may focus on high-quality handmade chocolates which is very different to Cadbury’s mass production approach). firms may operate in different countries where wages are different (e.g. many European companies relocated production to China); well-established firms can negotiate good bulk-purchasing discounts on raw materials, or carry out sound negotiations in the futures markets the internal structure of companies may be different, leading to different 60 levels of morale (workers with low morale are likely to produce less, leading to higher average costs)