Unit 7

advertisement

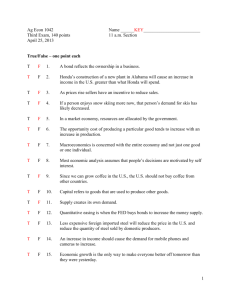

CHAPTERS IN ECONOMIC POLICY Part. II Unit 7 Uncertainty, Expectations and Economic Policy Should policymakers be restrained? - Frequent requests in US and Europe to restrain policymakers: i) In US there are frequent calls for the introduction of a balanced-budget amendment (e.g. this was the first item in the “contract with America”, the program drawn by the Republicans in the 1994): Figure 24 - 1 The Contract with America ii) In Europe the countries that adopted the Euro signed the “Stability and Growth Pact”, which required the government in the Eurozone to put budget deficits under control or face large fines - A major point: macroeconomic policymakers in general do not have all the knowledge required for solving complex macroeconomic problems - Furthermore, in market economies there is substantial uncertainty about the ultimate effects of policy measures. One of the reasons is the interaction of policy and expectations - During the 1960s Keynesian economists (F. Modigliani, P. Samuelson and others) believed that economists’ knowledge was becoming good enough to allow for increasing finetuning of the economy - M. Friedman: activist, discretionary policy is likely to do more harm than good - The interaction of policy and expectations: how a policy works depends not only on how it affects current variables but also on how it affects expectations about the future - In the past (during the 1960’s) economic policy was seen as the control of a complicated machine - Methods of optimal control were being used to design macroeconomic policy - However, outcomes in market economies are the result of the actions of people and firms who try to anticipate what policymakers will do and who react not only to current policy but also to expectations of future policy -Therefore, economic policy can be thought as a game between policymakers on the one side and the people and firms in the economy on the other -We don’t need optimal control theory but rather game theory, which studies strategic interactions between players - Strategic interaction: what people and firms do depends on what they expect policymakers to do. In turn, what policymakers do depends on what is happening in the economy - Sometimes, you can do better in a game by giving up some of your options e.g.: by giving up the option to negotiate, governments can prevent hostage takings in the first place - The same logic is involved in the design of macroeconomic policy to control inflation and unemployment Let’s recall a simple relation unemployment and inflation: e (u un ) between Inflation depends on expected inflation and on the difference between actual unemployment rate and the natural unemployment rate. The coefficient α captures the effect of unemployment on inflation (Time indexes are omitted for semplicity) - Let us assume that the Fed announces that it will follow a policy consistent with zero inflation. If people believe this announcement, πe = 0 - As a consequence, the Fed faces the following relation between unemployment and inflation: (u un ) - If the Fed follows through with its announced policy, it will “choose” an unemployment rate equal to the natural rate. Inflation would be zero as people expected - But the Fed could deviate from its stated policy and try to achieve an unemployment rate below the natural rate with just a small increase in the inflation rate. If = 1 and = 0, then (uun) = 1%. This incentive to deviate from the announced policy once the other player (in this case wage setters) has made its move is known as the time inconsistency of optimal policy. - However, wage setters revise their expectations and begin to expect positive inflation of 1% - If the Fed still wants to achieve an unemployment rate 1% below the natural rate, it will have to achieve 2% inflation - As a consequence, people revise their expectations for inflation further - Eventually, the economy returns to the natural rate of unemployment, but with higher inflation. - The best policy for a Central bank is therefore to make a credible commitment that it will not try to deviate from its announced target - By giving up the option of deviating from the announced policy, the Central bank can achieve u = un and zero inflation - How can a Central bank credibly commit not to deviate from its announced policy? - One radical way for a Central bank to establish its credibility is to be stripped by law of its policymaking power - The mandate of the Central bank can be defined by law in terms of a simple rule (e.g. setting money growth at 1%) - An alternative is to adopt a currency board - Of course, a constant money growth rule would prevent a Central bank to enact discretionary monetary policy (e.g.: expand money supply when unemployment is far above the natural rate) - There are better ways to deal with the problem of time inconsistency, without totally stripping policy-making power from the Central bank • These ways include: i) Make the Central bank independent: in this case it would be easier for the monetary authorities to resist political pressure ii) Give the central bankers long terms in office, so they have a long horizon and incentives to build credibility iii) Appoint a “conservative” central banker who utterly dislikes inflation -Over the past two decades, several countries adopted these measures, which on the whole have been quite successful - We have assumed so far that policy makers were benevolent – that they tried to do what was best for the economy - However much public discussion challenges this assumption: many policy decisions involve trading off short-run gains against long-run losses . • Tax cuts: - By definition, tax cuts lead to lower taxes today. They are also likely to lead to an increase in activity and income in the short run. - However, unless they are matched by decreases in government spending, tax cuts lead to larger budget deficit and to the need for an increase in taxes in the future - If voters are shortsighted, the temptation for politicians to cut taxes may prove irresistible . - With the right timing and shortsighted voters, political parties can win elections - Therefore, politics may lead to systematic deficits, until the level of government debt is so high that politicians are forced to act - More generally, by assuming that voters are shortsighted, politicians have a clear incentive to expand demand before an election - Indeed, excess demand cannot be sustained and eventually the economy should return to its structural level Yn - Thus, we might expect a clear political business cycle, with higher growth on average before elections than after elections How well do these arguments fit the facts? - An analysis of the evolution of the ratio of government debt to GDP in the US since 1900 shows that the reality is more complex: i) the major build-ups in debt were associated with special circumstances (World War I, the Great depression, World War II) ii) since the early 1980s, the argument of shortsighted voters and pandering politicians fits the facts much better much better Game theorists refer to situations in which each side (party) holds out, hoping the other side will give in, as wars of attrition E.g.: the party in power wants to reduce spending but faces opposition to spending cuts in Parliament One way of putting pressure on Parliament is to cut taxes and create deficits This puts increasing pressure to the Parliament to adopt measures aimed at reducing spending -These “wars” usually result in delays in the implementation of policy -This analytical framework explains to a large extent the rise in the ratio of debt to GDP in the US since the early 1980 -One of the goals of the Reagan administration when it decreased taxes from 1981 to 1983 was to create the conditions for spending cuts (Republicans in the US are traditionally against “big governments”) . The Stability and Growth Pact - In 1997 the would-be members of the Euro area agreed to make permanent some “convergence criteria” set by the Maastricht Treaty -In particular the members of the Eurozone should: i) commit to balance their budget in the medium run ii) avoid excessive deficits (deficits in excess of 3% of GDP) except under exceptional circumstances - Substantial sanctions were imposed on countries that ran excessive deficits - Indeed from 1993 to 2000 the performance of the countries in the Eurozone was very positive. Budget balances went from a deficit of 5.8% of Euro area GDP to a surplus of 0.1 - However, whilst the fiscal rules played a positive role, this performance was mainly the result of: i) The decrease in the nominal interest rate, which decreased the interest payment on the debt ii) The strong economic expansion in the late 1990s Since 2000 deficits have increased Main reason: low output growth which led to low tax revenue growth Some countries (Portugal, France, Germany) faced “excessive deficit” However, for obvious political reasons it was impossible to start the excessive deficit procedure against the latter two countries