Achalasia

advertisement

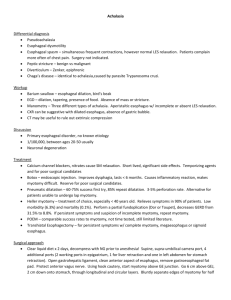

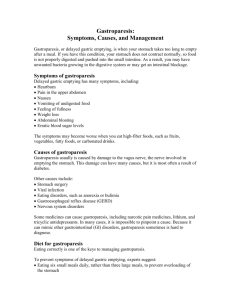

MOTILITY DISORDERS OF UPPER GI TRACT ACHALASIA GASTROPARESIS Tiberiu Hershcovici, MD Director, Gastrointestinal Motility Lab Hadassah University Hospital ACHALASIA DEFINITION CARDINAL SYMPTOM • Dysphagia to solids and liquids EPIDEMIOLOGY • • • • Incidence : 1 in 100,000 individuals annually Prevalence :10 in 100,000 There is no gender predominance. The disease can occur at any age, although diagnosis before the second decade is rare. • The incidence increases with age, with the highest incidence in the seventh decade and a second smaller peak of incidence at 20–40 years of age. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY • Normally, a food bolus introduced to the esophagus is moved to the stomach via a coordinated peristaltic wave and relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) • The disruption of these functions results from degeneration of ganglion cells in the myenteric plexus of the esophageal body and the LES. • The triggering event that leads to ganglion cell degeneration is unclear. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY • The esophageal plexopathy results in loss of nitric oxide (inhibitory neurotransmitter) in the LES and esophageal body. • This is associated with: – disruption of normal peristalsis – LES hypertonicity and incomplete relaxation of tone with swallowing SECONDARY ACHALASIA • Amyloidosis infiltrating the esophagus and LES • Extrinsic compression of the gastroesophageal junction: – tight fundoplication during antireflux surgery – laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LABG) • Infection by Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas disease) : – diffuse enteric myenteric destruction including small bowel dilatation and megacolon – heart disease – neurologic disorders SECONDARY ACHALASIA TO NEOPLASIA (PSEUDOACHALASIA) • Tumors that infiltrate the gastroesophageal junction may cause extrinsic pressure or direct tumor invasion of the myenteric plexus: – adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction or proximal stomach – pancreatic, breast, lung, or hepatocellular cancers • Paraneoplastic effect by secretion of an antineuronal antibody: small cell lung cancer CLINICAL PRESENTATION • Esophageal dysphagia (in up to 90% of patients) often for both solids and liquids • Chest pain • Heartburn and regurgitation • Weight loss CLINICAL PRESENTATION • More subtle symptoms owing to accommodation: slow eating, stereotactic movements with eating, and avoidance of social functions that involve meals. • The progression of symptoms in patients can be slow. • Many patients experience symptoms for years before coming to medical attention. DIAGNOSIS • Patients who have a history suggesting achalasia commonly require at least 2, and sometimes 3 modalities for diagnosis. • Barium esophagogram • Endoscopy • Esophageal manometry BARIUM ESOPHAGOGRAM • Dilated esophagus • Absence of peristalsis, • Narrowing of the distal esophagus in a typical “bird’s beak” appearance UPPER ENDOSCOPY • Endoscopic evaluation of the esophagus and stomach is recommended in every patient to ensure that there is not a malignancy causing the disease or esophageal squamous cell carcinoma complicating achalasia. • A dilated esophagus with a tight LES that “pops” open with gentle pressure is often observed, as well as retained food and saliva. ESOPHAGEAL MANOMETRY • The gold standard diagnostic modality for achalasia. • Manometrically, achalasia is defined by: – absence of peristalsis in the esophageal body – a poorly relaxing LES: • residual pressure > 8 mm Hg (classic manometry) • IRP > 15 mm Hg (high resolution manometry) HIGH-RESOLUTION MANOMETRY IRP=INTEGRATED RELAXATION PRESSURE IRP<15 mmHg TYPE I CLASSIC ACHALASIA complete absence of peristaltic contractile activity minimal pressurization TYPE II ACHALASIA absence of peristaltic contractile activity with panesophageal pressurization to a level 30 mmHg TYPE III ACHALASIA evidence of spasm using conventional criteria ACHALASIA DIAGNOSTIC FLOWCHART TREATMENT • Therapy focuses on relaxation or mechanical disruption of the LES. • There is no treatment method that addresses esophageal hypomotility. • Endoscopic Treatments: – Endoscopic botulinum toxin injection into the LES – Pneumatic dilation of LES • Surgery: – Esophagomyotomy (Heller myotomy) to divide LES from serosa to mucosa, thereby completely disrupting the muscular layers • Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM). TREATMENT • Pneumatic dilation and surgical myotomy effectively disrupt the LES and these therapies are comparable and much more effective than management with botulinum toxin or smooth muscle relaxants. • A recent randomized, multicenter, European trial compared the 2 modalities by assessing the outcome of 200 patients randomized to myotomy with Dor fundoplication or pneumatic dilation. • The success rates for these approaches after 2 years were both approximately 90% if one allowed a maximum of 3 dilations to be the equivalent of a single myotomy. European Achalasia Trial Prospective protocol using large number of patients to determine whether the pre-intervention subtype could predict outcome. Their results confirmed that after a minimum follow-up period of 2 years the overall outcomes of treatment (both surgery and dilatation) were significantly better in type II (96%) than type I (81%) and type III (66%) patients. However, their data do not support an initial observation that surgical myotomy is associated with better outcomes in types I and III achalasia. This could be related to the fact that the success rates of both techniques were very high. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) GASTROPARESIS DEFINITION • Gastroparesis is a syndrome characterized by delayed gastric emptying in absence of mechanical obstruction of stomach. CARDINAL SYMPTOMS • • • • Postprandial fullness (early satiety) Nausea Vomiting Bloating, particularly among women and overweight patients, and is severe in many individuals • Abdominal pain-predominant in the idiopathic type ETIOLOGY • Diabetes Mellitus -one third of cases • Idiopathic causes - one third of cases – post-viral gastroparesis • Other causes: – – – – postsurgical : vagotomy or vagal injury collagen vascular: scleroderma neurological disorders: Guillain-Barre syndrome medications: amylin analogs (e.g. pramlintide) or GLP-1 agonists (e.g. exenatide) that inhibit vagal function PATHOPHYSIOLOGY • Extrinsic autonomic neuropathy affecting the vagus nerve: – diabetes mellitus – postsurgical vagal injury • Intrinsic or enteric neuropathy: affecting excitatory and inhibitory intrinsic nerves, with loss of nNOS • Pathology of the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) • Myopathy: increased fibrosis of the muscle layer, hypoplasia, or degeneration of smooth muscle cells DIAGNOSIS • There is poor correlation between currently available methods to assess global gastric emptying and symptoms. • However, documentation of delayed gastric emptying to solids is required before a diagnosis of gastroparesis can be made. • Abnormal gastric emptying still remains the only objective marker of an underlying defect in the neuromuscular apparatus of the stomach. GASTRIC EMPTYING TESTS • Scintigraphy is the most common and widely available modality. The standard technique involves: – scintigraphic determination of emptying of a solid meal: 99mTc (technetium) sulfur colloid-labeled egg sandwich – it is required that scintigraphic measurement continues to 4 h. Shorter tests are not reliable. – Abnormal: gastric retention>10% at 4 h • Breath tests using non-radioactive forms of carbon(13C) incorporated in ingestible food. Advantages: – Can be carried out in office settings – Correlate well with scintigraphy DIAGNOSIS DIAGNOSIS • Gastroduodenal manometry can differentiate neuropathic from myopathic processes. • Neuropathic gastroparesis : – increased frequency of migrating motor complexes during fasting – reduced frequency of distal antral contractions postprandially (typically <1/ min during the first postprandial hour) – poorly developed intestinal fed pattern • Myopathic gastroparesis: – normal patterns of motility – low amplitude: • postprandial distal antral pressure activity is <40 mmHg • duodenojejunal pressure activity is <10 mmHg TREATMENT • Nutritional support • Prokinetics to improve gastric emptying: – metoclopramide – domperidone • Symptom control: for pain • Tight glycemic control in diabetes • Gastric electric stimulator in refractory cases NUTRITIONAL SUPPORT • • • • • Small frequent meals Well chewed food Avoid fiber Diet low in fat There are few data to show: – how these nutritional interventions compare with other treatment modalities for gastroparesis – if they affect the natural history and outcome of patients with diabetic gastroparesis. PROKINETIC MEDICATION – DOPAMINE ANTAGONISTS • Metoclopramide (Pramin) and domperidone (Motilium) are dopamine-2 receptor antagonists and equally effective in reducing symptoms of nausea and vomiting. • Metoclopramide is available in liquid and oral dissolving tablets which may be tolerated better. It has also been shown to be effective by the subcutaneous route, by passing issues associated with delayed gastric emptying. • A well recognised complication of metoclopramide is tardive dyskinesia that can be irreversible. • Domperidone does not cross the blood-brain barrier and is associated with fewer central nervous system effects. PROKINETIC MEDICATIONMOTILIN AGONISTS • Erythromycin is a potent prokinetic agent which acts by activating the motilin receptor, probably on the cholinergic neurons. • It is a useful agent for short-term treatment of patients in the hospital. • Its long-term benefit is limited due to development of tachyphylaxis. • Several other motilin agonists have been developed to avoid tachyphylaxis. They are still in phase of clinical trials. GASTRIC ELECTRICAL STIMULATION • Is being increasingly used for patients with diabetic gastroparesis with refractory nausea and vomiting. • Symptoms of nausea and vomiting improve with implantation of the device, as do quality of life and nutritional status. • The mechanism of action of gastric electrical stimulation is still not known. • It should be considered only in refractory diabetic gastroparesis after exhaustion of other therapeutic options and only when the main symptoms are nausea and vomiting and not pain. PAIN MANAGEMENT • Is often challenging in patients with gastroparesis as there is a lack of clear understanding of the physiological defect causing pain in these patients. • Tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants • Gabapentin and pregabalin • Opiates should be used very sparingly and only in refractory cases DIABET GASTROPARESIS PATHOPHYSIOLOGY