Why protected areas?

A report from IUCN-WCPA, The Nature Conservancy,

United Nations Development Programme,

Wildlife Conservation Society, The World Bank and WWF

“ This book clearly articulates for the first time how protected areas contribute significantly to reducing impacts of climate change and what is needed for them to achieve even more. As we enter an unprecedented scale of negotiations about climate and biodiversity it is important that these messages reach policy makers loud and clear and are translated into effective policies and funding mechanisms.”

Lord Nicholas Stern in his preface to Natural Solutions

Why protected areas?

• Protected areas are a proven effective governance system for managing land, coastal and marine ecosystems

• Protected area systems are already established as efficient, successful and cost effective tools for ecosystem management

• They have associated laws and policies, management and governance institutions, knowledge, staff and capacity

Why protected areas?

• They contain the only remaining large natural habitats in many areas

• Opportunities exist to increase their coverage of marine and coastal areas, connectivity at a landscape level and their effective management . All of which enhance the resilience of ecosystems to climate change and safeguard vital ecosystem services

Protected areas and climate change

• Protected areas are an essential part of the global response to climate change

• They can contribute to the two main responses to climate change through both:

Adaptation

and

Mitigation

Adaptation

The evidence for the role of using protected areas in ecosystem-based adaptation strategies

The challenge

• Ecosystem-based adaptation is the use of biodiversity and ecosystem services as part of adaptation strategies to help us cope with the adverse effects of climate change but

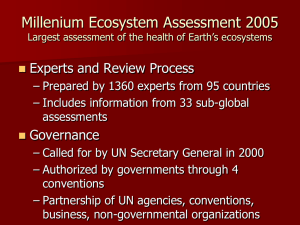

• The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment estimates that 60% of global ecosystem services are degraded and so these services are rapidly being lost

The impacts of degraded ecosystem services

• Health: spread of disease vectors, heat waves, poor sanitation due to lack of clean water

• Food: shortages and crop failure

• Water: shortages impacting drinking water, irrigation and hydropower potential

• ‘Natural disasters’: flooding, storms, drought, wildfire, pest infestations, ocean acidification

The opportunity

Protected areas provide two key functions

• Protect: maintain ecosystem integrity, buffer local climate, reduce risks and impacts from events such as storms and droughts and sea-level rise

• Provide: maintain essential ecosystem services that help people cope with changes in water supplies, fisheries, disease and agricultural productivity caused by climate change

Protecting ecosystem integrity

Protected areas can help to reduce the impact of all but the largest natural disasters, for example

• Floods: by providing space for floodwaters to disperse and through natural vegetation absorbing the impacts of flooding

• Landslides: by stabilising soil and snow to stop slippage or slow movement once a slip is underway

• Storm surges: intact natural systems such as coral reefs, barrier islands, mangroves, dunes and marshes can all help block storm surges

• Drought and desertification: effective management systems can control grazing pressure and intact watersheds help to keep vital water resources in soils

• Fire: natural vegetation can limit encroachment in fire-prone areas and the maintenance of traditional management systems can reduce fire risk

Provide natural resources

Protected areas are proven tools for maintaining essential natural resources and services, which in turn can help increase the resilience and reduce the vulnerability of livelihoods in the face of climate change

• Water: forest and wetland protected areas provide both purer water and

(especially in tropical montane cloud forests) increased water flow

• Fish resources: marine and freshwater protected areas conserve and rebuild fish stocks

• Food: by protecting crop wild relatives to facilitate crop breeding; through pollination services; and providing sustainable food supplies for communities

• Health: habitat protection to slow the expansion of vector-borne diseases that thrive in degraded ecosystems; as well as conserving traditional medicines and providing compounds for pharmaceuticals

Adapting to climate change

• Measures are needed to maintain the

resilience of ecosystems under new climatic conditions—so that they can continue to supply essential services

• Protected area management will need to be adapted, to address mitigation and adaptation needs, in addition to biodiversity management objectives.

How protected areas can deliver even more

• Understanding: assess and manage protected area services and benefits

• Adaptive management: consider climate impacts and climate solutions in protected area planning and management

• Integrate: include protected areas into national and local adaptation strategies

• Resilience: improve ecosystem resilience particularly when ecosystem services are under threat

• Restoration and connectivity: maintain and enhance ecosystem integrity

• Economics: realise the theoretical – goods and services from an effectively managed and representative protected area system could have a value of between US$4,400 and $5,200 billion a year. But protected area systems are currently underresourced and under-funded

The challenge for protected areas

• Integrity: ensure that protected areas are capable of delivering potential services by ensuring:

– Effective management of current areas

– More protection, particularly in underrepresented areas such as freshwater and marine areas

– Use of all governance and management types

• Trade-offs: guidance on how we manage climate impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem-based adaptation strategies

• Resilience: research and management advice to understand how we build resilience of protected areas

• Partnerships: with relevant sectors and communities – disaster relief agencies, seed companies, water companies, fishers, farmers etc

• Policy: enabling environment linking biodiversity and climate change policy

Mitigation

The potential to use protected areas in carbon storage and capture

The challenge

• Land use conversion is already responsible for around 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions

…and furthermore…

• According to the IPCC many ecosystems that are currently sinks for CO

2 could become sources of emissions, with a temperature increase of just 2.5

O C

The opportunity

Natural ecosystems offer two key functions

• Storing existing carbon in vegetation and soils and thus preventing further loss

• Capturing additional carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and thus reducing net greenhouse gas levels

Ruaha National Park, Tanzania

Carbon storage

• Natural ecosystems currently sequester about half of the current GHG emissions.

Major carbon stores exist in soil, forest, peat and inland waters, grassland, mangroves, coastal marshes and sea grass

• Estimates for the amount of carbon stored in tropical forests range from 170-250 t/ha. Temperate and boreal forests are also major sinks. The highest known carbon storage is in a Eucalyptus forest.

Kinabatangan Nature Reserve, Sabah, Malaysia, bottom inset from Lamington NP, Australia

Carbon storage

• Peat probably stores more – an estimated

550 Gt is stored globally. But 2008 emissions from degraded peat were estimated at 1,298 Mt, plus over 400 Mt from peat fires, threatening this store

• Mangroves, sea grass beds and salt

marshes all store substantial amounts of carbon although these sources have been largely ignored

Kinabatangan Nature Reserve, Sabah, Malaysia, bottom inset from Lamington NP, Australia

Carbon storage

• Grasslands may hold more than 10% of total carbon, but mismanagement and conversion is causing major losses – grassland are one of the most un-protected biomes

• Estimates of soil carbon vary but it is thought to be the largest terrestrial store.

Agriculture is often a source rather than sink but changes in farming (less tillage, more organic methods etc) can help build carbon stocks

Kinabatangan Nature Reserve, Sabah, Malaysia, bottom inset from Lamington NP, Australia

Carbon capture

Most ecosystems can also continue to capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere

Carbon capture

• Both young and old forests capture significant amounts of carbon dioxide, as do peatlands, grasslands and many marine ecosystems

• Research in the Amazon, Congo Basin and in boreal forests show that old-growth

forests continue to sequester carbon

• Sequestration from commercial forests depends largely on whether use is shortterm (e.g. newspapers) or long-term

Kinabatangan Nature Reserve, Sabah, Malaysia, bottom inset from Lamington NP, Australia

How protected areas can deliver

• Protected areas are the most effective tool yet found for maintaining carbon in natural vegetation

• The UNEP World Conservation

Monitoring Centre estimates that at least

15% of terrestrial carbon is stored in protected areas

Kinabatangan Nature Reserve, Sabah, Malaysia, bottom inset from Lamington NP, Australia

The challenge for protected areas

• New skills, tools and funding opportunities will be needed to make best use of available management options

• Gap analysis for protected area design may need to start including carbon

• New staff skills will be required

• Protected areas need to be included in

REDD and similar funding schemes

Policy responses

Opportunities to use protected areas in climate response strategies need to be prioritised in three key areas

Policy requirements

1. United Nations Framework Convention

on Climate Change (UNFCCC): needs to recognise protected areas as tools for mitigation and adaptation to climate change; and open up key climate change related funding mechanisms, including

REDD (Reducing Emissions from

Deforestation and Degradation) and adaptation funds, to the creation, enhancement and effective management of protected area systems

Policy requirements

2. Convention on Biological Diversity

(CBD): needs to renew the Programme of Work on Protected Areas at the 10 th

Conference of the Parties (COP10) in

2010 to address more specifically the role of protected areas in responses to climate change, in liaison with other CBD programmes

Policy requirements

3. National and local governments: although ecosystem-based solutions are not a panacea and should not replace attempts to reduce emissions from fossil fuel combustion, protected area systems should be incorporated into national climate change strategies and action plans, as tools for mitigation by reducing the loss and degradation of natural habitats, and adaptation by reducing the vulnerability and increasing reliance

Natural Solutions

• Natural Solutions is the first report to review the scientific literature in detail and make the case for the role of protected areas in climate change strategies

• The full report can be

downloaded at: cmsdata.iucn.org/download s/natural_solutions.pdf