0

OUR OCEAN PLANET

OUR OCEAN PLANET

SECTION 8 – OPEN OCEAN

1

REVISION HISTORY

Date

Version

Revised By

Description

Aug 25, 2010

0.0

VL

Original

8. OPEN OCEAN

8. OPEN OCEAN

2

8. OPEN OCEAN

The open ocean is vast. It covers an area of 361 million sq. km (139

million sq. miles) and more than 70% of the world’s surface. Much

of the ocean lies in the world’s tropical and sub-tropical areas, which

contains comparatively few nutrients and plankton. This massive

three-dimensional space is home to some of the most extraordinary

creatures on the planet, some of which must travel long distances up

and down the water column or across the open ocean to find food

and mates.

VERTICAL LAYERS

The open ocean is known as the pelagic realm. It contains several

vertical layers or zones with different characteristics. The layers

form a physical and chemical barrier to different organisms and few

organisms can move easily between them. The main vertical zones

are:

1. Neuston Layer

The topmost meter of the ocean is completely different from the rest

of the water mass. It is called the “neuston layer” and is

comparatively rich in nutrients because many of the waste chemicals

excreted by plankton in deeper water float to the surface and

concentrate there. This chemically enriched environment provides

and ideal habitat for bacteria, unicellular protozoans and microscopic

algae.

3

8. OPEN OCEAN

2. Photic Zone (Surface)

The top 200 m (656 ft) of water is warm, highly mixed, and

effectively floats upon the colder, denser water below. It is the sunlit

zone of the ocean and is limited to the maximum depth sunlight can

penetrate. The photic zone is where phytoplankton is found since

they need sunlight for photosynthesis. It is also where most animals

are found at night.

Under water, the colours of the visible spectrum are absorbed by

water with increasing depth. Red will disappear at a depth of around

6 m (20 ft), orange at 9 m (30 ft), yellow at 18 m (60 ft) and green at

21 m (70 ft). By 30 m (100 ft), everything appears blue or greyish

green. At greater depths, all visible light is absorbed and everything

appears dark blue or black.

3. Twilight Zone (Intermediate)

Below the photic zone lies the colder and denser intermediate layer

called the twilight zone which lies between 200 m and 1000 m (656

ft and 3,300 ft). The twilight zone is where most animals are found

during the day.

4. Dark Zone (Deep)

Below 1,000 m (3,300 ft), the water is extremely heavy, dense, and

cold. It is also completely dark. In spite of these difficult conditions,

however, deep sea life can be found here.

4

8. OPEN OCEAN

TEMPERATURE & OXYGEN BARRIERS

The different layers of the ocean are physically and chemically

different. The water temperature and the amount of dissolved

oxygen play important role in partitioning life vertically in the ocean.

For example;

1. Temperature

The layers have different temperatures and thermoclines (lines of

temperature differences) form. In the tropics, the surface zone water

may be as warm as 25°C (77°F) while the intermediate zone water

temperature may be just 11°C (50°F). In the dark zone, the water

becomes much colder, 5°C (41°F).

The main ocean thermocline lies within the intermediate zone. This

is a permanent feature that is rarely broken down and it proves an

impenetrable barrier to most marine life because it cannot cope with

the sudden change in temperature. By and large, this thermocline

separates the ocean’s upper-water organisms from those in the

deep.

2. Oxygen Minimum Layer

Another boundary exists within the intermediate zone. This is the

oxygen minimum zone and marks the level below which dissolved

oxygen in the water is at its minimum. Few organisms from the

warm oxygen-rich surface waters above can survive in these

oxygen-depleted conditions.

5

8. OPEN OCEAN

OVERTURN

Anything that is heavier than water sinks under gravity so many

dying organisms and nutrients fall through the thermocline into the

deep zone below.

If the ocean was static, these sources of food

would be lost to the life in the surface layer.

Fortunately, in polar and temperate oceans, in a process called

“overturn”, winter chilling causes the surface water to become so

dense that it sinks into the deep ocean forcing nutrient-rich water up

from the bottom.

Winter storms further mix the water layers, ensuring that oceans in

the far north and south of the world have high nutrient levels and can

support the massive plankton populations in the summer months.

Tropical and sub-tropical oceans, however, do not experience

sufficient cooling to allow overturn to occur so here the stable

surface zone contains vastly fewer nutrients than the deep zone.

REFERENCES & FURTHER READING

Byatt, Andrew, Fothergill, Alastair and Holmes, Martha, The Blue

Planet: Seas of Life, Chapter 6, DK Publishing Inc., (2001), ISBN 07894-8265-7

6

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

7

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

8.1.1 Vertical Migrations

In the open ocean during the day, there are very few places animals

can hide from predators. In order to avoid predators, therefore, most

animals hide in the twilight zone (200-1,000 m / 656-3,300 ft) where

they are less easily seen by predators that hunt mainly by sight.

Thus, during the day, the photic zone only contains about 10% of the

total marine life, while 75% is found in the twilight zone.

At night, however, the amount of life at the surface quadruples to

40% as a result of mass vertical migrations. Every night, millions of

tonnes of animals undertake the largest mass migration on Earth

journeying up from the ocean’s twilight zone to the photic zone in

search of food. In the middle of the night, the top 30 m (98 ft) of the

ocean teems with feeding plankton. At dawn, the same animals will

return to the twilight zone.

The extent of the vertical migration up and down the water column

varies between species. The smallest plankton probably travel just

10-20 m (33-66 ft) while larger animals may travel as much as 1000

m (3,300 ft).

As the zooplankton travel up and down the water column, so follow

their predators, including fish such as anchovies, mackerel and

herring, and jellyfish. In turn, predators of these fish and jellyfish,

such as sharks, dolphins and turtles, follow.

8

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

9

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

8.1.2 Migrations Across Oceans

Some animals undertake immense journeys across the oceans in

search of food and breeding grounds. The following are some of the

extraordinary travelers that undertake these great migrations across

the oceans:

1. Arctic Terns

Arctic terns fly between the Arctic and Antarctic regions to enjoy two

summers a year. They travel further than any other bird. Some

Arctic terns fly more than 35,000 km (21,000 miles) in a year from

the Arctic to the Antarctic and back!

2. Grey Whales

Grey whales swim more than 22,000 km (13,600 miles) a year

between their Arctic feeding grounds and their breeding grounds off

California. No other mammal migrates as far.

3. Wandering Albatrosses

The wandering albatross spends most of its life circling the globe

north of Antarctica. This seabird travels up to 12,000 km (7,500

miles) before returning briefly to land to breed.

4. Green Turtles

Every 2-3 years, female green turtles leave their feeding grounds off

Brazil and travel to Ascension Island in the middle of the Atlantic

Ocean where they were born. Here, they lay their eggs before

returning across the sea again. How they navigate this 2,000 km

(1,250 mile) journey is not known but some possible mechanisms

include their using currents, seamounts or the Earth’s magnetic field.

10

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

11

5. Spiny Lobsters

Migrating spiny lobsters form “lobster trains” and match head to tail

along the seabed to protect themselves from enemies.

6. European Eels

The European eel has an amazing life cycle. From 4 to 18 years of

age, it lives in freshwater rivers and lakes. When it reaches

adulthood, it heads downstream towards the ocean. On reaching

the sea, it changes to saltwater life and heads into the open ocean.

Heading south and west, it swims 6,000 km (3,700 miles) to the

Sargasso Sea. Here, at a depth of 700 m (2,300 ft), it meets up with

thousands of other eels and spawns in the deep cold water. The

effort is terminal and all adult eels die. Their microscopic larvae

spend 3 years growing up in the plankton and following the Gulf

Stream past the Caribbean and back across the Atlantic. In their 4th

year, the young eels wriggle and slip their way up the rocky slopes

of European rivers to spend their next 14 years in freshwater.

7. Salmon

Salmon hatch in freshwater streams but mature at sea. They will

return just once to the streams of their birth to spawn and die. Some

adults will travel thousands of miles to reach the river where they

hatched.

Interesting!

The longest recorded migration

of any marine vertebrate goes to

a leatherback turtle. Scientists

from NOAA initially tagged an

animal in Papua, Indonesia and

tracked its movements for 647

days to the coast of Oregon in

the USA – a one-way swim of

20,558 km (12,774 miles) across

the Pacific Ocean.

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

12

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

13

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

14

REFERENCES & FURTHER READING

http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/worldonthemove/ - Migrations

http://www.seaturtlestatus.org – Sea Turtle migrations

Byatt, Andrew, Fothergill, Alastair and Holmes, Martha, The Blue Planet: Seas of Life, Chapter 6, DK

Publishing Inc., (2001), ISBN 0-7894-8265-7

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

8.1.3 Open Ocean Life

15

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

ALBATROSS

An albatross (Diomedeidae spp.) aloft is a magnificent sight. These

birds weigh up to 10 kg (22 lb) and have the longest wingspan of

any bird – up to 3.4 m (11 ft). The wandering albatross is the

biggest of some two dozen different species.

Albatrosses use their huge wings to ride the ocean winds and can

glide for hours without rest or even a flap of their wings. They also

float on the sea's surface though this makes them vulnerable to

aquatic predators. Albatrosses drink salt water, as do some other

sea birds. Albatrosses feed on squid or schooling fish but are

familiar to mariners because they sometimes follow ships in the

hope of dining on handouts.

These long-lived birds reach 50 years of age. They are rarely seen

on land and gather only to breed at which time they form large

colonies on remote islands. Some species mate for life. Mating

pairs produce a single egg and take turns caring for it. Young

albatrosses may fly within 3-10 months and then leave land behind

for some 5-10 years until they themselves reach sexual maturity.

16

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

PORTUGUESE MAN-OF-WAR

The Portuguese man-of-war (Physalia physalis) is a siphonophore – an

animal (cnidarian) made up of a colony of organisms working together.

A man-of-war comprises four separate polyps. It gets its name from the

uppermost polyp, a gas-filled bladder called a float or pneumatophore, which

sits above the water and resembles an old warship at full sail. Man-of-wars

are also known as bluebottles for the purple-blue colour of their

pneumatophores. The float may be 30 cm (12 in) long and 12.7 cm (5 in)

wide. The tentacles are the man-of-war's second organism. These long, thin

tendrils can extend 50 m (165 ft) in length below the surface, although 10 m

(30 ft) is more average. They are covered in venom-filled nematocysts used

to paralyze and kill fish and other small creatures. For humans, a man-ofwar sting is excruciatingly painful but rarely deadly. Muscles in the tentacles

draw prey up to a polyp containing the digestive organisms (gastrozooids)

while the fourth polyp contains the reproductive organisms.

Man-of-wars are found, sometimes in groups of 1,000 or more, in warm

waters of throughout the world's oceans. They have no independent means

of propulsion and either drift with the currents or catch the wind with their

pneumatophores. To avoid surface threats, they can deflate their air bags

and submerge.

17

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

LEATHERBACK TURTLE

Leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) are the world’s largest

turtles growing up to 2.6 m (8.5 ft) in length and 907 kg (2,000 lb) in weight.

While all other sea turtles have hard, bony shells, the smooth, black

carapace of the leatherback is soft and almost rubbery to the touch.

They may live over 45 years but human threats, such as fishing lines and

nets, mean most leatherbacks meet an early end. Other threats include

illegal egg harvesting and loss of nesting habitat. Hatchlings often die when

beachfront lighting draws them away from the ocean and hundreds die at

sea when they swallow plastic which they mistake for jellyfish – their main

food. They can dive to 1,230 m (4,035 ft) and remain submerged for 35

minutes.

In all, only about 1 in 1,000 leatherbacks survives to adulthood. The

worldwide population is estimated at about 26,000-43,000 nesting females

annually, but they are suffering exponential declines and are critically

endangered throughout their range and now teeter on the brink of extinction.

Their enormous range comprises the tropical and temperate waters of the

Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans. Unlike other reptiles, their body

temperature stays well above the surrounding water and they have been

found in the icy seas as far north as British Columbia, Canada, and as far

south as the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa.

18

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

OCEAN SUNFISH

The ocean sunfish (Mola mola) is the heaviest bony fish in the world.

It has an average length of 1.8 m (5.9 ft) and an average weight of

1,000 kg (2,200 lb) although individuals up to 3.3 m (10.8 ft) in

length and weighing up to 2,300 kg (5,100 lb) have been observed.

The species is native to tropical and temperate waters around the

globe. It resembles a fish head without a tail and its main body is

flattened laterally. Sunfish can be as tall as they are long when their

dorsal and anal fins are extended.

Sunfish mainly eat jellyfish. As this diet is nutritionally poor, they

consume large amounts in order to develop and maintain their great

bulk. Females of the species can produce more eggs than any other

known vertebrate. Sunfish fry resemble miniature pufferfish with

large pectoral fins, a tail fin and body spines uncharacteristic of adult

sunfish.

Adult sunfish are vulnerable to few natural predators but sea lions,

orcas and sharks will consume them. Among humans, sunfish are

considered a delicacy in some parts of the world, including Japan

and Taiwan but sale of their flesh is banned in the European Union.

Sunfish are often accidentally caught in gill nets and are also

vulnerable to injury or death from encounters with floating rubbish,

such as plastic bags.

19

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

BOTTLENOSE DOLPHIN

Bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) are well known as the

intelligent and charismatic stars of many aquarium shows. In the

wild, these sleek swimmers can reach speeds of over 30 kph (18

mph). They surface often to breathe, doing so two or three times a

minute. They reach 4.2 m (14 ft) in length and weigh 500 kg (1,100

lb) and can live 50 years.

Dolphins often eat bottom-dwelling fish as well as shrimp and squid.

Bottlenose dolphins track their prey through the use of echolocation.

They can make up to 1,000 clicking sounds per second. These

sounds travel underwater until they encounter objects, then bounce

back to their dolphin senders, revealing the location, size, and shape

of their target.

Bottlenose dolphins travel in social groups and communicate with

each other by a complex system of squeaks and whistles. Schools

have been known to come to the aid of an injured dolphin and help it

to the surface.

Bottlenose dolphins are found in tropical oceans and other warm

waters around the globe. They were once widely hunted for meat

and oil (used for lamps and cooking) but today only limited dolphin

fishing occurs. However, dolphins are threatened by commercial

fishing for other species, like tuna, and can become entangled in

nets and other fishing equipment.

20

Interesting!

All dolphins, including the

bottlenose, are porpoises.

Although some people use these

names interchangeably,

porpoises are actually a larger

group that also includes animals

like killer whales (Orca) and

beluga whales.

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

WHALE SHARK

The whale shark (Rhincodon typus) is the largest fish in the sea with

a length of 18.3 m (60 ft) length. The whale shark's flattened head

sports a blunt snout above its mouth with short barbels protruding

from its nostrils. Its back and sides are gray to brown with white

spots among pale vertical and horizontal stripes, and its belly is

white. Its two dorsal fins are set rearward on its body, which ends in

a large dual-lobbed caudal fin (or tail).

Whale sharks eat plankton which they filter from the water. They

scoop tiny animals and plants, along with any small fish that happen

to be around, with their colossal gaping mouths while swimming

close to the water's surface. It then shuts its mouth, forcing water

out of its gills and filtering out the food.

Whale sharks are found in all tropical seas. They migrate every

spring to the continental shelf of the central west coast of Australia.

The coral spawning of the area's Ningaloo Reef provides the whale

shark with an abundant supply of plankton.

Whale sharks are currently listed as a vulnerable species. However,

they continue to be hunted in parts of Asia, such as Taiwan and the

Philippines.

21

22

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

BLUE MARLIN

The blue marlin (Makaira nigricans) is the largest of the Atlantic

marlins and one of the biggest fish in the world. Females, which are

significantly larger than males, can reach 4.3 m (14 ft) in length and

weigh more than 900 kg (1,985 lb). Females can live up to 27 years

in the wild.

Native to the tropical and temperate waters of the Atlantic, Pacific,

and Indian Oceans, blue marlins are among the most recognizable

of all fish. They are cobalt-blue on top and silvery-white below with

a pronounced dorsal fin and a long, lethal spear-shaped upper jaw.

They are so-called blue-water fish, spending most of their lives far

out at sea. They are also highly migratory and will follow warm

ocean currents for thousands of kilometers.

Blue marlins prefer the higher temperature of surface waters,

feeding on mackerel and tuna, but will also dive deep to eat squid.

They are among the fastest fish in the ocean, and use their spears

to slash through dense schools, returning to eat stunned and

wounded victims.

Their meat is considered a delicacy, particularly in Japan, where it is

served raw as sashimi.

Although not currently endangered,

conservationists worry that they are being unsustainably fished,

particularly in the Atlantic.

Interesting!

It is a blue marlin that the old

fisherman battles in Ernest

Hemingway's classic story “The

Old Man and the Sea”.

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

THRESHER SHARK

The thresher shark (Alopias vulpinas) is an oceanic deep-water

shark. It has a pointed snout and 5 gills slits in front of each pectoral

fin. It also has an extremely long upper lobe in caudal fin that often

exceeds length of body. The tail used to herd and stun prey. It is

often found in large numbers and is considered a large and

dangerous shark especially during maritime disasters. The thresher

shark feeds on fishes and squids and can reach 6.1 m (20 ft) length

and weigh 454 kg (1,000 lbs).

SHORTFIN MAKO

The shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus) is a member of the mackerel

shark family. It is a slender, bullet-nosed shark that is bright blue to

slate blue above and white below and can reach 3.7 m (12 ft) in

length. Its front teeth are long, narrow, curved with no cusps at

base. It is a very swift and active shark that hunts tuna and other

fish. It is possibly the fastest swimming shark.

23

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

ATLANTIC BLUEFIN TUNA

The Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) is one of the largest,

fastest and most beautiful of the world’s fishes. Their torpedoshaped, streamlined bodies are built for speed and endurance.

Their colouring (metallic blue on top and shimmering silver-white on

the bottom) helps camouflage them from above and below. Their

voracious appetite and varied diet pushes their average size to 2 m

(6.5 ft) in length and 250 kg (550 lb) although they can reach twice

this size.

Atlantic bluefins are warm-blooded, a rare trait among fish, and are

comfortable in the cold waters off Newfoundland and Iceland, as well

as the tropical waters of the Gulf of Mexico and the Mediterranean

Sea, where they go each year to spawn. They are among the most

ambitiously migratory of all fish, and some tagged specimens have

been tracked swimming from North American to European waters

several times a year. They can live 15 years in the wild.

They are prized among sport fishermen for their fight and speed,

shooting through the water with their powerful, crescent-shaped tails

up to 70 kph (43 mph). They can retract their dorsal and pectoral fins

into slots to reduce drag. Some scientists think the series of “finlets”

on their tails may reduce water turbulence.

24

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

Bluefins attain their enormous size by gorging themselves almost

constantly on smaller fish, crustaceans, squid, and eels. They will

also filter-feed on zooplankton and other small organisms and have

even been observed eating kelp. The largest tuna ever recorded

was an Atlantic bluefin caught off Nova Scotia that weighed 679 kg

(1,496 lb).

Bluefin tuna have been eaten by humans for centuries. In recent

years demand and prices for large bluefins soared worldwide,

particularly in Japan, and commercial fishing operations found new

ways to find and catch these sleek giants. As a result, bluefin

stocks, especially of large, breeding-age fish, have plummeted, and

international conservation efforts have led to curbs on commercial

takes. Nevertheless, at least one group says illegal fishing in

Europe has pushed the Atlantic bluefin populations there to the brink

of extinction.

25

Interesting!

We often say that reptiles or fish are

cold-blooded and mammals are

warm-blooded. However, many

scientists try not to use these terms

because they are not precise and,

in some cases, inaccurate.

More precisely, some animals, such

as mammals are able to regulate

their body temperature above that

of the environment’ – these animals

are “homeothermic” – which means

they are able to keep their body

temperature constant. In contrast,

animals, such as most reptiles and

fish, cannot regulate their body

temperature and are called

“poikilothermic”. These animals rely

on warmth from the sun and the

environment to warm them up.

While most reptiles and fish cannot

regulate their body temperature,

there are exceptions. For example,

the Leatherback turtle is a reptile

that is able to regulate its

temperature while the bluefin tuna is

a fish that is able to do so.

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

ATLANTIC MANTA

The Atlantic Manta (Manta birostris) is an oceanic ray and is a

member of the devil ray family. Its body is dark brown or black

above and white below, and it has long and pointed pectoral fins

(their “wings”). Manta rays also have two large cephalic (head) fins

that look like “horns” hence their “devil” ray name. They have short

whip-like tails with no spines on them. They also have a wide,

terminal mouth wide which they use to feed on plankton and small

fishes. They can reach 6.7 m (22 ft) across their wings and weigh

1,814 kg (4,000 lbs).

26

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

ELEPHANT SEAL

There are two species of elephant seals (Mirounga spp.) – northern

and southern. Northern elephant seals can be found in California

and Baja California though they frequent offshore islands rather than

the North American mainland. Northern elephant seals live an

average of 9 years in the wild.

Southern elephant seals live in sub-Antarctic and Antarctic waters.

These are cold waters but they are rich in the fish, squid, and other

marine foods these seals enjoy. Southern elephant seals breed on

land but spend their winters in Antarctic waters near the Antarctic

pack ice.

Southern elephant seals are the largest of all seals. Males can be

over 6 m (20 ft) long and weigh up to 4,000 kg (8,800 lb). However,

these massive pinnipeds aren't called elephant seals because of

their size but take their name from their trunk-like inflatable snouts.

Southern elephant seals can dive over 4,921 ft (1,500 m) deep and

remain submerged for up to two hours. Southern elephant seals live

20 to 22 years.

27

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

When breeding season arrives, male elephant seals define and

defend territories. They collect a harem of 40-50 females, which are

much smaller than their enormous mates. Males battle each other

for mating dominance. Elephant seals give birth in late winter to a

single pup after an 11 month pregnancy and nurse it for

approximately a month. While suckling their young, females do not

eat. Both mother and pup live off the energy stored in the reserves

of her blubber.

Elephant seals were aggressively hunted for their oil and their

numbers were reduced to the brink of extinction. Fortunately,

populations have rebounded under legal protections.

28

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

29

SAILFISH

Sailfish (Istiophorus platypterus) range throughout the warm and

temperate parts of the world’s oceans. They are blue to gray in

colour with white underbellies. They get their name from their

spectacular dorsal fin that stretches nearly the length of their body

and is much higher than their bodies are thick.

Sailfish are members of the billfish family and, as such, have an

upper jaw that juts out well beyond their lower jaw and forms a

distinctive spear. They are found near the ocean surface usually far

from land feeding on schools of smaller fish like sardines and

anchovies which they often shepherd with their sails. They also feed

on squid and octopus.

Their meat is tough and not widely eaten but they are prized as

game fish. These powerful, streamlined fish can grow to more than

3 m (10 ft) and weigh up to 100 kg (220 lb). In the wild, they live

about 4 years. Sailfish are fairly abundant throughout their range

and their population is considered stable. They are under no special

status or protections.

Interesting!

Sailfish are the fastest fish in the

ocean and have been clocked

leaping out of the water at more

than 110 kph (68 mph).

8.1 LIFE IN THE OPEN

REFERENCES & FURTHER READING

http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/birds/albatross.html - Albatross

http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/portuguese-man-of-war.html

http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/reptiles/leatherback-sea-turtle.html

http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/bottlenose-dolphin.html

http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/elephant-seal.html - Elephant seal

http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/bluefin-tuna.html - Atlantic Bluefin Tuna

http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/blue-marlin.html - Blue Marlin

http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/whale-shark.html - Whale shark

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ocean_sunfish - Ocean sunfish

30

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

31

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

8.2.1 Sharks & Rays

SHARKS

DESCRIPTION

Sharks have 5-7 pairs of gill slits – usually 5 pairs

Gill slits on lateral side of body

Most sharks have several rows of sharp pointed teeth

Fusiform shape – cylindrical and tapered at both ends

Extremely varied in size

Heterocercal caudal fin – upper tail fin lobe longer than lower

May or may not have a spiracle behind each eye

May or may not have a nictitating membrane (“eyelid”) over eye

Predators include other sharks, killer whales, and Man

Marine but a few species (e.g. Bull Shark) can enter fresh water

Sharks swim with their caudal fin (tail) and form an “S” shape with their body and tail

SIZE

Largest – Whale shark – 18.3 m (60 ft) length

Smallest (probably) – Spined pygmy shark (Squaliolus laticaudus) – 0.2 m (6 in)

Sexual dimorphism – females grow ~25% larger than males in most shark species

Of 355 species, only 39 exceed 3.1 m (10 ft) in length while 176 species stay under 0.8 m (39 in)

32

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

RAYS (BATOIDS)

DESCRIPTION

Nearly all rays have 5 pairs of gill slit openings

Gill slits and mouth on the ventral side of the body

Pectoral fins enlarged & attached to sides of head

Rhomboid or circular shape

Caudal and dorsal fins reduced, sometimes absent

No anal fin

All rays have large spiracles to take in water for respiration

All lack nictitating membrane on the eye

Predators include sharks and Man

Largest family within the rays are the skates

Electric ray family can generate powerful electrical charges

Sawfish family use their “saws” for hunting

Most rays are bottom dwellers but some are pelagic (e.g. mantas)

As a group, very successful in colonizing the deep sea

Mostly marine but some (e.g. sawfishes) can enter fresh water; a few live only in fresh water

Most rays swim by flapping their pectoral fins (“wings”) but guitarfishes & sawfishes swim like sharks

SIZE

Largest – Manta Ray – 6.7 m (22 ft) across wings and 1,814 kg (4,000 lbs)

33

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

SCALES

Sharks and batoids have placoid scales which are also often called

“dermal denticles” (“skin teeth”). Placoid scales and teeth have the

same structure, consisting of 3 layers:

• Outer layer of vitro-dentine (an enamel)

• Dentine

• Pulp cavity

Placoid scales give the skin a tough sandpapery texture. Shark and

batoid skin was formerly valued as a source or leather and as an

abrasive called “shagreen”

Placoid scales are arranged in a regular pattern in sharks and an

irregular pattern in batoids.

Some rays are covered with denticles (small prickles) while others

are naked or have only small patches of denticles. Many have a

median (middorsal) row of enlarged denticles (spines) down the

back and tail. In stingrays and their relatives, some tail denticles are

modified into long barbed spines – these and the spines at the front

of the dorsal fins are commonly called “stings” and can cause severe

wounds.

34

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

TEETH & JAWS

Teeth are modified, enlarged placoid scales

Size and shape of teeth vary enormously

Sharks

Can be serrated wedges, smooth & pointed or blunt for crushing

Bite force exerted by some sharks up to 8,000 PSI

Often possess multiple rows of teeth

Rows of teeth roll forward replacing old, broken or missing teeth

A shark's jaws are loosely connected to the rest of the skull at two

points. As the upper jaw extends forward from the mouth, teeth of the

lower jaw first encounter prey. The lower jaw teeth puncture and hold

prey while the upper jaw teeth slice.

Rays

Stingrays and eagle rays have teeth that are fused into plates

Flattened teeth suited to grinding or crushing shellfish

Some skates have many rows of teeth – Winter Skate >72 rows

Filter-feeders have reduced non-functional teeth. Devil rays, basking

and megamouth sharks strain plankton from the water with gill rakers

(filaments composed of thousands of tiny “teeth”). Whale sharks

strain plankton through a spongy tissue supported by cartilaginous

35

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

DIET

Sharks eat almost anything: fishes, crustaceans, molluscs, marine

mammals, sea birds, and other sharks and rays. Most rays eat

clams, mussels, and oysters but rays also eat a variety of fishes,

squids, and crustaceans. For example:

Sharks

Bull sharks eat fishes & other sharks

Great white sharks eat sea lions & other marine mammals

Hammerhead sharks eat fishes & stingrays

Wobbegongs eat shrimps

Tiger sharks eat several species of sea turtles & sea birds

Whale and basking sharks feed on plankton

Rays

Sawfishes – eat fishes

Electric rays – eat bottom organisms, flounders and small sharks

Stingrays – eat clams and oysters

Eagle rays – eat molluscs

Manta rays – strain plankton from the water

36

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

BREEDING & REPRODUCTION

All sharks and rays utilize internal fertilization

“Claspers” – male sex organs in cartilaginous fish; modified pelvic

fins

Clasper is turned forward and inserted into female cloaca

Sharks can be oviparous, ovoviviparous or viviparous

Skates lay eggs but other rays are ovoviviparous

Eggs are often called “Mermaid’s Purses”

Oviparous (“egg-laying”) – e.g. Horn Shark, Skates

Eggs are laid by the female and develop outside her body. The

eggs contain yolk and provide nourishment to the growing embryo.

Ovoviviparous (“egg & live-bearing”) – e.g. Sand Tiger Shark

Fertilized eggs develop within the female but the embryo gains no

nutritional substances from the female. As a result, once the egg

yolk runs out, young must eat other eggs or one another to survive

(“uterine cannibalism”).

Viviparous (“live-bearing”) – e.g. all Hammerhead and Requiem

Sharks (except the Tiger Shark which is ovoviviparous).

Shark embryo develops inside the body of the female from which it

gains nourishment through a complex yolk-sac placenta. Female

37

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

38

SENSES

Sight

Sharks have a basic vertebrate eye but it is laterally compressed; lens is large and spherical

Eyes are particularly sensitive to moving objects

In clear water, a shark's vision is effective at a distance up to ~15.2 m (50 ft)

Unlike those of other fishes, a shark's pupil can dilate and contract

Cone cells are present indicating sharks may have some colour vision

Eyes have numerous rods that detect light intensity changes making sharks sensitive to contrast

Sharks see well in dim light. Eye has a layer of reflecting plates (“tapetum lucidum”) behind the retina.

These plates act as mirrors to reflect light back through the retina a second time.

Smell

Sharks have an acute sense of smell & can detect minute quantities of substances in water (e.g. blood)

Can detect concentrations as low as one part per billion of some chemicals (e.g. certain amino acids)

A shark’s sense of smell functions up to hundreds of meters (yards) away from a source

Nurse sharks have “barbels” near their nostrils which enhance tactile or chemo receptors

Taste

Sharks and batoids have taste buds inside their mouths

Taste may be responsible for a shark's final acceptance or rejection of prey items

Some sharks prefer certain foods and will spit out things that have an unpleasant taste

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

39

Acoustic

Sharks have an inner ear only; use sound to initially detect prey

The lateral line system is a series of fluid-filled canals just below the skin of the head and along the

sides of the body. The canal is open to the surrounding water through tiny pores. The lateral line canals

contain a number of sensory cells called neuromasts. Tiny hair-like structures on the neuromasts project

out into the canal. Water movement created by turbulence or vibrations displaces these hair-like

projections, stimulates the neuromasts, and triggers a nerve impulse to the brain. Like the ear, the

lateral line senses low-frequency vibrations.

Sensory Pit

A sensory pit is formed by the overlapping of two enlarged placoid scales guarding a slight depression

in the skin. At the bottom of the pit is a sensory papilla: a small cluster of sensory cells that are probably

stimulated by physical factors such as water currents. Sensory pits are distributed in large numbers on

the back, flank, and lower jaw.

Electrical – Ampullae Of Lorenzini

External pores dot the surface of a shark's head. Each pore leads to a jelly-filled canal that leads to a

membranous sac called an ampulla. In the wall of the ampulla are sensory cells innervated by several

nerve fibres. These ampullae detect weak electrical fields generated by all living organisms and are

used to help detect prey in the final stages of prey capture. The ampullae may also detect temperature,

salinity, changes in water pressure, mechanical stimuli, and magnetic fields.

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

INTERESTING FACTS

Sharks

Sharks can detect electrical impulses generated by the muscles of

other animals through the ampullae of Lorenzini.

Sharks are often known as “obligate ram ventilators” – this means

sharks are obliged to keep moving to ram or force water through

their gills in order to ventilate or breathe. However, it is not true that

ALL sharks must constantly keep moving in order to breathe – some

(such as whitetip reef shark and nurse shark) can rest on the sea

floor and pump water over their gills.

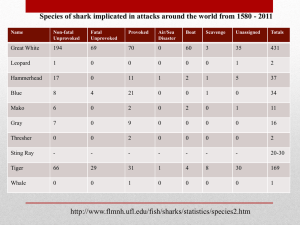

Only a comparatively small number of sharks are dangerous to

Man – of 355 species, about 25 are known to have attacked Man

and another 40 are potentially dangerous.

Sharks may or may not have a nictitating membrane. This is an

eyelid-like structure which is drawn over the eye to give it extra

protection from injury caused by thrashing prey. When a shark,

such as the Great White, bites its prey, it does not actually see what

it is biting as each eye is covered by a nictitating membrane at the

last moment. Rays do not have nictitating membranes over their

eyes.

40

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

Rays

Some skates have numerous rows of teeth. For example, Winter

Skates have 72 or more rows of teeth (usually > 80) in upper jaw!

Sawfish use their “saws” to scythe through schools of fish when

hunting prey.

Sawfishes are ovoviviparous – eggs are retained in uterus and live

young are born with their saw encased in a sheath to protect the

mother.

Some rays, such as the Atlantic Torpedo, have electric organs

capable of delivering powerful electric shocks (~200V).

41

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

42

THREATS

Sharks have been around for hundreds of millions of years but they are seriously threatened today.

Sharks reach sexual maturity slowly and have few young. In addition, as a top predator, their actual

numbers are comparatively small. The primary threat to their continued existence is probably humans.

Threats include:

Pollution

Sharks are often caught as a by-catch and discarded

Sport and trophy hunting

Use of shark cartilage and other body parts in both Eastern and Western medicine

Fishing – people eat the pectoral fins (“wings”) of certain rays; fins also used to make Shark’s Fin Soup

“Finning” – cutting the fins off sharks and then discarding the body

Perhaps the greatest challenge with shark conservation is convincing people of the need to protect them

.

Sharks often eat sick and weak prey. This actually improves the gene pool for the stronger, healthier

individuals that go on to reproduce. Shark over-fishing removes this vital link in the delicate balance of

the ocean ecosystem.

When sharks were over-fished around Australia, the octopus population increased dramatically. The

octopus then preyed heavily on spiny lobsters and decreased that population. By destroying sharks,

therefore, humans may unwittingly be removing a key that keeps ocean populations healthy.

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

43

CONSERVATION

Fisheries management programs are necessary for a sensible shark harvest. As of 2007, only the

United States, New Zealand, and Canada have started shark management plans.

In 1993, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) implemented a plan to manage U. S. shark

fisheries of the Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Mexico, and Caribbean Sea. This plan included:

o Annual commercial quotas, which are divided into half- yearly quotas.

o Provisions for closing a fishery for a species group when the semi-annual quota is met.

o Catch limits for recreational anglers.

o Permit requirements for commercial vessels that catch sharks.

o A requirement that vessels land fins in proportion to carcasses (effectively prohibiting the

practice of shark finning).

o A requirement that when sharks are not kept, they are released in a manner that ensures the

probability that they will survive.

The state of California passed a law the same year totally protecting the great white shark.

The law set forth by NMFS placed limits on 22 species of large coastal, seven species of small coastal,

and 10 pelagic species of sharks. A yearly catch limit of 5.4 million pounds of sharks still failed to stop

declining shark populations. In the spring of 1997, NMFS cut the quota of large sharks to 1.285 metric

tons, limited the catch of small coastal sharks, and banned the commercial harvest of whale, great white,

basking, sand tiger, and bigeye sand tiger sharks.

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

CLASSIFICATION

44

45

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

SHARK ORDERS & FAMILIES

Approximately 8 orders, 30 families and 355 species

Order Hexanchiformes

Family Hexanchidae – cowsharks, 6-gill & 7-gill sharks *

Family Chlamydoselachidae – frilled sharks

Order Pristiophoriformes

Family Pristiophoridae – sawsharks

Order Squatiniformes

Family Squatinidae – angelsharks

Order Heterodontiformes

Family Heterodontidae – horn sharks *

Order Orectolobiformes

Family Orectolobidae – wobbegong sharks

Family Ginglymostomatidae – nurse sharks *

Family Rhincodontidae – whale shark *

Family Parascylliidae – collared carpet sharks

Family Brachaeluridae – blind sharks

Family Hemiscylliidae – bamboo sharks *

Family Stegostomatidae – zebra sharks

* Discussed here

Order Squaliformes

Family Squalidae – dogfishes

Family Echinorhinidae – bramble sharks

Family Oxynotidae – rough sharks

Order Lamniformes

Family Odontaspididae – sand tiger sharks *

Family Mitsukurinidae – goblin shark

Family Lamnidae – mackerel sharks *

Family Cetorhinidae – basking shark *

Family Alopiidae – thresher sharks *

Family Pseudocarchariidae – crocodile sharks

Family Megachasmidae – megamouth shark

Order Carcharhiniformes

Family Scyliorhinidae – catsharks

Family Proscylliidae – ribbontail catsharks

Family Psoudotriakidae – false catsharks

Family Leptocharildae – barbeled houndsharks

Family Triakidae – smoothhound sharks *

Family Hemigaleidae – weasel sharks

Family Carcharhinidae – requiem sharks *

Family Sphyrnidae – hammerhead sharks *

46

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

RAY ORDERS & FAMILIES

Approximately 4 orders, 11 families, and 470 species

Order Rajiformes

Family Rajidae – skates *

Family Rhinobatidae – guitarfish *

Order Torpediniformes

Family Torpedinidae – electric rays *

Order Pristiformes

Family Pristidae – sawfish *

* Discussed here

Order Myliobatiformes

Family Dasyatidae – stingrays *

Family Myliobatidae – eagle rays *

Family Mobulidae – devil rays *

Family Rhinopteridae – cownosed rays *

Family Urolophidae – round stingrays

Family Gymnuridae – butterfly rays

Family Potamotrygonidae – river rays

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

SHARK SPECIES

1. WHALE SHARK – RHINCODON TYPUS

Whale Shark Family

Grey-brown with distinctive pattern of yellow or white spots and bars

Caudal fin nearly vertical; upper lobe much longer

3 prominent ridges along each side of back

Teeth tiny and numerous

Feeds mainly on plankton but will eat fishes and squid

Each eggs is in a large, horny case

Largest fish and also largest shark

To 18.3 m (60 ft) length

2. BASKING SHARK – CETORHINUS MAXIMUS

Basking Shark Family

Dark grey or slate-coloured above; lighter below

Gill slits very long – across entire side & nearly meeting below

Each gill has long, closely set gill rakers that strain plankton from

water

Mouth large, teeth tiny

Sheds gill rakers in winter, goes to bottom and fasts while new gill

rakers grow

Generally harmless but its size can make it hazardous to small boats

Often hit by ocean-going ships

To 13.7 m (45 ft) length

47

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

3. WHITE SHARK – CARCHARODON CARCHARIAS

Mackerel Shark Family

Slate blue or leaden grey above, dirty white below

Heavy body, large head, pointed snout

Teeth large and triangular with serrated edges

Largely oceanic but will stray in coastal waters

Large & dangerous shark made infamous through “Jaws”

To 7.9 m (26 ft) length but usually less than 4.9 m (16 ft)

4. SHORTFIN MAKO – ISURUS OXYRINCHUS

Mackerel Shark Family

Bright blue to slate blue above, white below

Slender bullet-nosed shark

Front teeth long, narrow, curved with no cusps at base

Very swift and active shark

Possibly the fastest shark – hunts tuna

Important game fish

Frequently marketed as “swordfish”

To 3.7 m (12 ft) length

48

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

5. TIGER SHARK – GALEOVERDO CUVIERI

Requiem Shark Family

Brownish grey above, whitish below with conspicuous dark blotches

and bars.

Snout short and broadly rounded from below

Spiracle present

Teeth broad and coarsely serrated with deep notch on outer edge

Mostly pelagic but commonly enters shallow bays to feed

Large and dangerous shark, known to attack Man

To 7.3 m (24 ft) length

6. BULL SHARK – CARCHARHINUS LEUCAS

Requiem Shark Family

Gray to dull brown above, white below

Heavy body

Snout short, very broad and rounded from below

Upper teeth nearly triangular, serrated

Common large shark in coastal water

Also found in rivers and lakes; survives well in fresh water.

Implicated in several attacks on humans in NJ rivers

To 3.5 m (11.5 ft) length

49

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

7. SANDBAR SHARK – CARCHARHINUS PLUMBEUS

Requiem Shark Family

Heavy body

Dark grey to brown above; becoming paler below

Infamous relatives are bull, tiger and oceanic whitetip sharks

Bears live young (like all requiem sharks)

To 3.1 m (10 ft) length

8. WHITETIP REEF SHARK – TRIAENODON OBESUS

Requiem Shark Family

Small, slender shark

Extremely short, broad snout, oval eyes

Spiracles usually present

Gray above, lighter below and sometimes with dark spots on sides

First dorsal-fin lobe and dorsal caudal-fin lobe with conspicuous

white tips

Second dorsal-fin lobe and ventral caudal-fin lobe often white-tipped

Viviparous

Sluggish inhabitant of lagoons and seaward reefs

Often found resting in caves or under coral ledges during the day

More active at night

Feeds on benthic animals such as fishes, octopi, spiny lobsters and

crabs

To 2.1 m (7 ft) length

50

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

9. BONNETHEAD SHARK – SPHYRNA TIBURO

Hammerhead Shark Family

Head spade shaped

Small harmless species

Feeds mainly on crustaceans

Bears live young (like all hammerheads)

To 1.5 m (5 ft) length

10. NURSE SHARK – GINGLYMOSTOMA CIRRATUM

Nurse Shark Family

Rusty brown with small yellowish eyes

No nictitating membrane on eye

Mouth small; teeth in a crushing series

Feeds on crustaceans and shellfish

Use their thick lips to create suction and pull prey from holes &

crevices

Has “barbels” (“whiskers”) front edge of each nostril

Barbels used to find food on the ocean bottom.

Caudal fin with no distinct lower lobe

Will bite if provoked but otherwise relatively harmless

Large eggs in horny capsules

To 4.3 m (14 ft) length but usually less than 3.1 m (10 ft)

51

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

11. SAND TIGER – ODONTASPIS TAURUS

Sand Tiger Family

Greyish brown or tan above with dark spots especially towards the

tail

Paler below

All 5 gill slits in front of pectoral fins

Teeth long and curved, pointed, non-serrated – feeds on fish

Sluggish species

Not known to attack man, in spite of ferocious appearance

1 or 2 young retained in oviducts; feed on eggs produced by mother

To 3.2 m (10.5 ft) length

12. THRESHER SHARK – ALOPIAS VULPINAS

Thresher Shark Family

Oceanic deep-water sharks

Extremely long upper lobe in caudal fin (often exceeds length of

body)

Pointed snout

5 gills slits in front of each pectoral fin

Tail used to herd and stun prey

Often occur in large numbers

Considered dangerous especially during maritime disasters

Feeds on fishes and squids

Corral schools of fish using the long upper lobe of their tails

52

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

13. SIXGILL SHARK – HEXANCHUS GRISEUS

Hexanchidae Family

Six gill slits

Long caudal fin

Six large trapezoidal teeth on each side of lower jaw

Coffee-coloured to brown or greyish on back, paler below

Mostly in deep water

Spiracle present

Live bearing

To 4.9 m (16 ft) length and 590 kg (1,300 lbs)

14. HORN SHARK – HETERODONTUS FRANCISCI

Horn Shark Family

Tan to dark brown with black spots above; pale yellowish below

Snout short and blunt

Ridge above eye

2 dorsal fins each with a spine

Sluggish, solitary, active at night

Eats crabs and small fishes

Lays large (to 5”) eggs – eggs have spiral flanges

To 0.9 m (3 ft) length

53

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

15. WHITE-SPOTTED BAMBOO SHARK – CHILOSCYLLIUM

PLAGIOSUM

Bamboo Shark Family

Nostrils sub-terminal on snout

Caudal fin with a pronounced notch but without a ventral lobe

Transverse dark bands and numerous white or bluish spots

Oviparous

A common but little-known inshore bottom shark

Utilized for human consumption and used in Chinese medicine

To 0.8 m (2.5 ft) length

16. LEOPARD SHARK – TRIAKIS SEMIFASCIATA

Smoothhound Shark Family

Broad black bars, saddles and spots

Snout short, bluntly rounded

Feed mainly on crabs, shrimps, bony fish – large variety of food in

diet

Strong-swimming, nomadic

Ovoviviparous with 4-29 in a litter

Good for human consumption

To 2.1 m (7 ft) length

54

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

RAY SPECIES

1. ATLANTIC MANTA – MANTA BIROSTRIS

Devil Ray Family

Dark brown to black above, white below

Pectoral fins long and pointed

Two large cephalic (head) fins – look like “horns” (hence “devil”

rays)

Mouth wide, terminal

Tail whip-like but short and no spine

Oceanic

Feeds on plankton and small fishes

To 6.7 m (22 ft) across wings and 1,814 kg (4,000 lbs)

2. SPOTTED EAGLE RAY – AETOBATUS NARINARI

Eagle Ray Family

Disk dark grey to brown above with a pattern of white spots and

streaks

Whitish below

Long graceful wings (pectoral fins)

Long whip-like tail with a long spine near base

Frequently seen in large schools during non-breeding season

To 2.4 m (8 ft) across wings and 227 kg (500 lbs)

55

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

3. COWNOSE RAY – RHINOPTERA BONASUS

Eagle Ray Family

Dark brown to olive above with no spots or marks

Snout squarish with an indentation in the centre

Free-swimming ray that swims by flapping its pectoral fins

Eats molluscs

Whip-like tail with venomous spine (note: spine venomous, not the

tail itself)

Oceanic; sometimes jumps out of the water and slaps back down

Several theories as to why this occurs; e.g. parasite removal but

probably more to do with territorial display

Frequently gathers in large schools

Bears live young (like all eagle rays)

To 0.9 m (3 ft) across disk

4. SOUTHERN STINGRAY – DASYATIS AMERICANA

Stingray Family

Disk almost perfect rhombus

Most stingrays are bottom-dwellers

Often lie submerged in sand except for the eyes

Whip-like tail with venomous spine (note: spine venomous, not the

tail itself)

Generally stingrays will not bite, sting or hurt you although you may

be stung if you inadvertently step on one

Bears live young (like all stingrays)

To 1.5 m (5 ft) across disk

56

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

5. ROUGHTAIL STINGRAY – DASYATIS CENTROURA

Stingray Family

Disk with numerous scattered spines

Tail with numerous rows of small spines

One of the largest stingrays

Similar to Southern Stingray

To 2.1 m (7 ft) across disk and 4.3 m (14 ft) long

6. YELLOW STINGRAY – UROLOPHUS JAMAICENSIS

Stingray Family

Disk almost round

Tail stout with spine placed back

Disk yellowish with dark spots

Common ray from Florida to northern South America

To 0.4 m (14 in) across disk and 0.7 m (26 in) long but usually much

smaller

57

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

7. WINTER SKATE – RAJA OCELLATA

Skate Family

Disk broad, rhombic-shaped and spotted

Tail thick – not whip-like – tail never has a large spine or “sting”

Usually 1-4 ocelli on each side of disk

At least 72 rows of teeth (usually > 80) in upper jaw

Bottom-dweller

Good for human consumption

To 1.1 m (43 in)

8. ATLANTIC GUITARFISH – RHINIOBATOS LENTIGINOUS

Guitarfish Family

Pectoral fins joined in front to head

Spiracles large

Gill slits and mouth on underside

Long triangular disk; thick, tapered body

Brownish above usually with many small white spots below

To 0.8 m (30 in)

58

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

9. SMALLTOOTH SAWFISH – PRISTIS PECTINATA

Sawfish Family

Pectoral fins joined in front to head

Spiracles large

Gill slits and mouth on underside

“Saw” is about ¼ length of the fish

24 or more teeth on each side of “saw”

Caudal fin has no distinct lower lobe

Not aggressive and no threat to man unless caught and handled

Saws are dried and sold as souvenirs

Moves its head from side to side and scythes/strikes prey with its

long rostrum

May also use the front of its snout to dig for prey buried under sand

To 5.5 m (18 ft)

10. ATLANTIC TORPEDO – TORPEDO NOBILIANA

Electric Ray Family

Disk round without spines

Chocolate to dark grey above without spots, whitish below

Produce 200V but not generally aggressive

Kidney shaped electric organ found on each side of the head

Sluggish bottom-dwellers

Feeds on other bottom-dwellers including flounders and small

sharks

To 1.8 m (6 ft) and 91 kg (200 lbs)

59

8.2 OCEAN LIFE

60

REFERENCES & FURTHER READING

http://www.elasmodiver.com - Sharks, rays and chimaeras

http://www.seaworld.org/animal-info/info-books/sharks-&-rays/index.htm - Sharks and rays

Robins, C.R. et al., A Field Guide to Atlantic Coast Fishes of North America, Houghton Mifflin Pub.

(1986)

8.3 ACTIVITIES

8.3 ACTIVITIES

61

8.3 ACTIVITIES

8.3 ACTIVITIES

8.3.1 Sharks

CORE ACTIVITY

(a) Colour the great white

shark slate grey above and

white below, and add the

following labels to your picture:

• Dorsal Fin

• Caudal Fin (Tail)

• Pectoral Fin

• Gill Slits

• Jaws

• Snout

• Eye

62

8.3 ACTIVITIES

(b) Name several dangerous sharks

(c) What is the world’s largest shark? What does it eat?

(d) How many senses does a shark have and what are they? How many senses does a human have?

63

8.3 ACTIVITIES

ANSWERS

(a) Colour the great white

shark slate grey above and

white below, and add the

following labels to your picture:

• Dorsal Fin

• Caudal Fin (Tail)

• Pectoral Fin

• Gill Slits

• Jaws

• Snout

• Eye

64

8.3 ACTIVITIES

65

(b) Name several dangerous sharks

The great white, tiger, and bull sharks are known to be dangerous sharks

(c) What is the world’s largest shark? What does it eat?

The world’s largest shark (and fish) is the whale shark. It primarily eats plankton but it will also eat fishes

and squid.

(d) How many senses does a shark have and what are they? How many senses does a human have?

A shark has 6 senses

• Sight

• Smell

• Touch

• Hearing

• Taste

• Electrical

A human has 5 senses; we have all the senses a shark has except the electrical sense.

8.3 ACTIVITIES

8.3.2 Rays

CORE ACTIVITY

(a) Colour the Southern

stingray dark grey, and add

the following labels to your

picture:

• Spines

• Tail

• Sting (barb)

• Eye

• Pectoral Fin

• Rhomboid Disk

(b) What is the world’s largest ray? What does it eat?

66

8.3 ACTIVITIES

ANSWERS

(a) Colour the Southern

stingray dark grey, and add

the following labels to your

picture:

• Spines

• Tail

• Sting (barb)

• Eye

• Pectoral Fin

• Rhomboid Disk

(b) What is the world’s largest ray? What does it eat?

The world’s largest ray is the manta ray. It eats plankton and small fishes.

67