Cactoblastis

advertisement

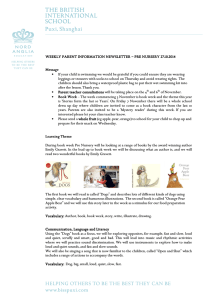

Biological Control and Invasive Invertebrates M.L. Henneman Biological Control (=“biocontrol”): humans manipulating interactions between species in order to control a species considered to be a pest Examples of Biological Control Classical Biocontrol •animal herbivore or pathogen (ex. fungus) introduced to feed on plant pest •animal predator or parasite introduced to feed on animal (usually insect) pest * If the target pest is native, sometimes the term “Neoclassical” biocontrol is used. Types of Biological Control Conservation Biocontrol • enhancing conditions under which a natural herbivore, predator, or parasite of a pest thrives Types of Biological Control Augmentation Biocontrol • artificially rearing above agents to augment natural numbers Success with classical biocontrol (= alien target species) • Sugarcane leaf hopper and egg predators • Hibiscus mealy bug (invaded Grenada in 1993) and parasitic wasp Anagyrus kamali (Encyrtidae) • Prickly pear cactus and Cactoblastis moth Sugarcane leaf hopper and egg predators The sugarcane leafhopper (Perkinsiella saccharicida) is native to Australia, and was a significant pest in sugarcane-growing regions throughout the world (though interestingly, it is restricted to Florida in the Caribbean region). Biology of sugarcane leafhopper - Females live a month and lay up to 300 eggs - Damage is caused by insects sucking the sap from sugarcane - Result is dead leaves, and sooty mold growing from the honeydew produced by the insects - It is also a vector of Fiji disease, a virus that makes tumors in the plant Sugarcane leaf hopper and egg predators The egg predator Tytthus mundulus, an Australian true bug from a family of mostly plant-feeders, produced almost miraculous results when introduced to sugar-growing areas. Currently, sugarcane leafhopper is suppressed to the point where it is no longer an economically damaging pest. Savings to the sugarcane industry have been estimated to be US$600 million. Pink Hibiscus Mealybug • Originally from India • Invaded Grenada in 1993 • Extreme generalist – attacks hundreds of species in 200 genera, including hibiscus, citrus, coffee, sugar cane, annonas, plums, guava, mango, okra, sorrel, teak, mora, pigeon pea, peanut, grape vines, maize, asparagus, chrysanthemum, beans, cotton, soybean, cocoa, and many other plants. • From 1994-1997, damage in Grenada estimated at US$3.5-10 million Pink Hibiscus Mealybug PHM has up to 15 generations per year. As it feeds, it injects toxic saliva that stunts growth and can kill a plant when heavily infested. Pesticides and mechanical control were not effective in the Caribbean. Pink Hibiscus Mealybug control A tiny parasitic wasp, Anagyrus kamali, became instrumental in control of pink hibiscus mealybug. Because its life cycle is half the length of its host, the pest was quickly overwhelmed wherever the wasp was introduced. Prickly pear cactus and Cactoblastis • Prickly pear from Brazil was introduced to Australia with the first white settlers in the 1700s in order to establish a cochineal dye industry • By the early 1900s, prickly pear had overrun large parts of Queensland and New South Wales – 30 million acres in Queensland were completely covered. • in 1925, the cactus-feeding moth Cactoblastis cactorum was introduced to Australia with amazing results Prickly pear cactus and Cactoblastis Prickly pear cactus and Cactoblastis Before After Prickly pear cactus and Cactoblastis “In 1925, prickly pear, the greatest example known to man of any noxious plant invasion, infested fifty million acres of land in Queensland, of which thirty million represented a complete coverage… This plaque, affixed by the Queensland Women's Historical Association … records the indebtedness of the people of Queensland and Dalby in particular, to the Cactoblastis cactorum and their gratitude for deliverance from that scourge.” Cactoblastis was dispersed around the world Cactoblastis was dispersed around the world • Cactoblastis was introduced to Nevis in the 1950s to control native prickly pear that were considered a nuisance on rangeland. (= Neoclassical biocontrol) • It has now spread throughout the Caribbean to Florida, where it is threatening several species of native prickly pear. Cactoblastis U.S. distribution Cactoblastis cactorum detections in the Southeastern United States SC MS AL GA Charleston 2009 LA Mobile Pensacola Tallahassee New Orleans FL Farthest Western Outbreak: Delta area south of New Orleans Tampa N 0 50 100 2008 2007 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1993 1989 200 mi Miami Oct. 1989 First Continental US Detection – Bahia Honda Key, FL Cactoblastis in the U.S. • It is being monitored closely, because if it reaches Mexico, it could not only threaten more species of prickly pear, but it could cause significant economic damage. • Biological control using parasitic wasps that attack Cactoblastis is now being studied. Disasters in classical biocontrol • Cane toads and mongooses - many sugarcane growing regions (birds) • African land snail and cannibal snail (hundreds of species of endemic snails) • Gypsy moth and Compsilura concinnata fly (giant silk moths) ----> Generalists = non-target interactions! Specialists can cause problems too • Cactoblastis is a specialist • Indirect effects: control of bitou bush weed in Australia by a seed predator has artificially increased numbers of a native parasitic wasp species (Willis and Memmott, 2005) Bitou control may cause indirect effects Conclusions • Success stories in biocontol are well outnumbered by failures – roughly 1 in 6 biocontrol agents are considered successful, and this ignores potential harm caused. • Classical biocontrol should be used carefully, and neoclassical biocontrol should not be practiced. We need to increase monitoring. • Current practitioners of biocontrol insist that it is now safely practiced; but we have controlled only the problems we can control. • We have no idea what impact most invertebrate biocontol agents are having; because invertebrates are not easily studied, or even noticed, this “absence of evidence” is clearly not the same as “evidence of absence” of negative effects to the ecosystem.