- Food Research Collaboration

advertisement

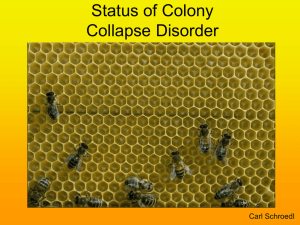

Let’s re-instate the hyphen: agri - culture Jane Dixon, Australian National University Food Thinkers@City University, October 2014 The problem with food culture: 2013 talk Healthy eating practices: culture in consumption • Moral arts of everyday life • De-legitimisation of traditional & bureaucratic authorities, and rise of charismatic, commercial authorities • The corporate shaping of a culinary culture which favours: cheap, convenient & novel • (Affluent) consumer demand for particular cultural qualities/values (convenience, health) affects supply 2 Message: 2014 talk Ignoring the cultural dimensions within agriculture has implications for: Farming system viability: agriculture without farmers? Environmental sustainability: the metabolic rift Nutrition security: another form of metabolic rift 3 Culture: a blue print for action; evolves; is powerin-action Ideas, knowledge, language, discourses and practices... a blueprint guiding but not dictating what is imaginable, moral and doable; it evolves and is contested culture forms part of the multi-factorial exercise of power operating in concert with social, economic and environmental/natural factors operates at multiple levels: global, nation state, village/community, household and individual levels (Banwell, Ulijaszek & Dixon 2013) 4 CAN A CULTURAL LENS MAKE SENSE OF AGRICULTURAL TRANSITIONS AND FUTURES? 5 THE DIFFUSION OF THE CONTRACT MODEL OF FARMING 6 The contract model of labour relations A history: US • 1930s: Emerges in Northeast as system of independent companies selling to urban markets • 1940s-1950s: Relocates to US South to take advantage of lowwage workers, marginal land for production, and history of sharecropping • 1950s-1960s: Vertical integration based on contract production rationalizes the industry and increases efficiency; independent system disappears • 1980s-2000s: Contract poultry growers organize and complain to US government of integrator monopsony opportunism based on debt bondage • 1970s-2010s: US poultry model diffused to other countries by poultry TNCs: Purina, Tyson, Pilgrim, Cargill (Constance et al. 2014) Cultural processes facilitate flows of ideas, norms and practices Key processes include: imposition through rules or laws; socialisation and peer pressure; diffusion of innovations, emulation, mimesis; commodity use (Banwell, Ulijaszek & Dixon 2013) 9 THAILAND Range of production sectors The Kitchen to the World • commercialize agriculture and bring farmers into the cash economy • small holder farmer participation in agribusiness dominated, export-oriented production • rural Thai incomes rise, purchase food products they do not produce themselves and become more food secure (Kelly et al. under review) 13 International agency support for contract farming • provides participants with inputs, advice and guaranteed market • enables poor farmers to overcome entry barriers and participate in global value chains • leads to poverty reduction and rejuvenation of small scale agriculture • leads to emergence of a prosperous Smalley 2013 peasantry Qualifying the benefits • The contracts are not the outcome of equal participation or power • Leads to a loss in autonomy of the farmer • Contracting firms benefit from the self exploitation of peasants, and deskills them turning them into piece workers • Contracting firms benefit from donor agencies which support smallholder contract farming • Unintended consequences on rural society cohesion – insider-outside differentiation (Smalley 2013) The ‘sufficiency economy’ • Move small landholders towards selfreliant farms: with 4 zones for water storage, rice cultivation, fruit and vegetable crops and practice animal husbandry. • The practice of low chemical, sustainable mixed agriculture • Subsistence versus sufficiency production (Kelly et al. under review). 16 Implications for nutrition, bio-security & the environment: ungeneralisable & contestable • Thai farmers are amongst the poorest citizens (Kelly et al. 2014 ) • “[A] premodern agricultural system – based on pigs, ducks, chickens and centuries-old technology – could well turn out to be the greatest threat to the postmodern food system” (Watson referring to SARS in China, 2008) • Contract farming has introduced more fertilisers, vet medicines and pesticides than earlier mixed farms... (sometimes necessary!) 17 THE BEE KEEPER VERSUS THE CONSERVATIONIST 18 Honeybee ecologies • Like humans, honeybees have specific dietary requirements: proteins, carbohydrates, minerals, fatty acids, vitamins and water • like humans, healthy bees can better resist diseases • Australia’s native forests provide the European honeybee with the richest diet on earth. 19 European honey bee*: globally • 35% of the world’s crops depend on animal pollination (Klein 2007) • Absence of animal pollination estimated to reduce agricultural production by 3-8% (Aizen 2009) • Agricultural intensification not the answer: lack of suitable ag. lands; cost of inputs becoming more expensive; intensification “jeopardizes wild bee communities and their stabilizing effect on pollination services at the landscape scale” (Klein 2007, p. 303) 20 The European honey bee: Australia • Honey production, bees wax = $60m pa • Pollination services to agriculture ($4-8b) Many crop and pasture species are heavily or totally reliant on bees for pollination. Commercial prosperity within the agricultural sector requires bees. So does the food security of Australia… BUT: 1700 commercial beekeeping businesses, average age = 54, income = $15400, education = year 10 (RIRDC 2010) 21 Threats to E. honeybee industry sustainability • Pests: small hive beetle, Asian bee/ Varroa mite • Falling price paid by honey processors & growing competition from imported honey • Lack of demand for urban orchard pollination service • Urban development destroying timber stands & diminished access to parks, so on the road for more weeks agisting hives (Dixon 2013; Edwards & Dixon in press) 22 Feral honeybees “disrupt complex plant-pollinator systems which have evolved between native plants and animals over 1000s of years” (Environment Conservation Council Victoria, 2001: p. 75) 23 Government regulations: E. honeybee • 1 of 36 Key Threatening Processes (KTP), (with a KTP defined under the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 as “Something that threatens or could potentially threaten the survival or evolutionary development of a species, population or ecological community”: NSW Environment & Heritage, 2011) • “...beekeeping is inconsistent with the management principles of National Park Tenure” (Queensland Government) • Co-existence, but apiary viewed alongside mining in national park – ie low on priorities (Victorian Government) 24 Hot topics in invasive science “What should be done in those rare circumstances when invasive species provide valued ecosystem services or support threatened and endangered species?” (Union of Concerned Scientists 2001) 25 Sustainability use for conservation Let’s recognise the essential role of use of nature and living natural resources as part of an overall conservation strategy (UN World Conservation Strategy 1980) 26 Proactive environmentalism now The honeybee industry stands for and depends on the preservation of native flora and hence has much in common with those in the community whose values support nature conservation and the establishment of conservation reserves (AHBIC, 2007, p.9) • Actively pursue a tree planting program on own properties • Encourage Landcare groups to plant known high value nectar & pollen plants • Address or pass on to interested parties information on the value of various floral species as a resource for nectar and pollen... 27 Dominance of contract farming practices & A conservation system of belief as nature-human separation IMPLICATIONS OF AGRICULTURE FOR AGRICULTURALISTS 28 Revisiting the ‘agrarian question’ • What position in the social class structure/hierarchy do farmers occupy? • Status linked to relationship to land/the means of production & how labour is rewarded and by whom.... 29 Depeasantisation or agriculture without farmers? neo share-cropping production regime as corporate capital invests in, sells and moves production enterprises from one locale to another, engaging producers under tenuous contracts... began with poultry, now extends to all commodity sectors (Constance et al 2014) Re-peasantisation • pursuit of autonomy through managing a self-controlled resource base • distanced from markets in terms of inputs, but linked to other markets on the output side • disposition for co-production, not with other value chain actors located in commodity markets, but with nature and with local social networks and knowledges (van de Ploeg 2008) 31 Cultural heritage: a helpful policy support for agriculture? The intangible cultural heritage, transmitted from generation to generation, is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interactions with nature and their history, and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity, thus promoting respect for cultural diversity and human creativity (2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage) 32 CONCLUSIONS 33 The cultural turn remains invisible within agri-food studies • With exception of consumption practices – mainstream vs alternative foodways; consumer views of risk • Occasional glimpses in: Textual analyses of government or corporation documents looking for modes of power/governance Actor network analyses of conventions Postmodern interpretation of landscape values Food Regimes theorising when considering ‘hidden’ forms of power: environmentalism, nutritionalisation 34 Culture as a repertoire of capacities • Possessed by producers, consumers & networks alike • Variable in time, space, social grouping/network • Mobilised in different ways depending on historical and structural relations & economic resources • Cultural contestations and flux-in-cultural identity are important to identify because when circumstances are unsettled, social changes/agri-food transitions follow 35 Farmers as cultural actors artisan, creator, scientist, educator, conservator? their styles of farming, and associated rhythmic activities and value systems, are pivotal to food system (un)sustainability 36