fire regimes

advertisement

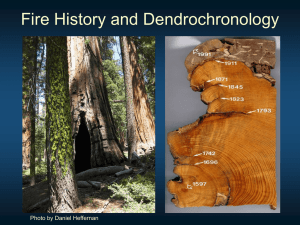

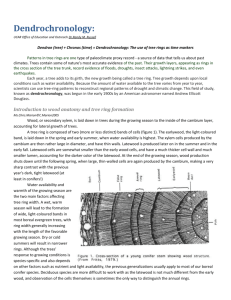

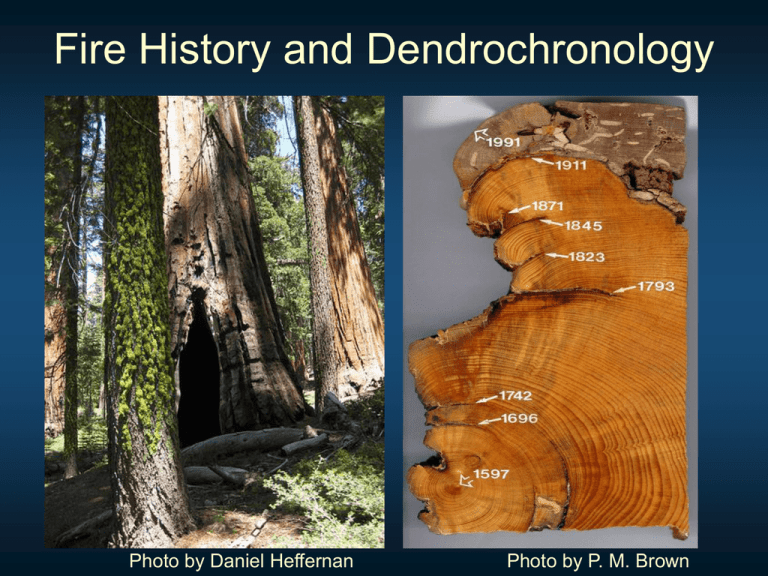

Fire History and Dendrochronology Photo by Daniel Heffernan Photo by P. M. Brown Agenda: April Fool’s Day 2011 • • • • • • Notes on burn plans Fire history lecture Break Lab Done Credits- Debra Kennard, Laboratory of Tree Ring Research, H. D. Grissino’s Ultimate Tree Ring webiste How do we know what the “natural” or historical fire regime is for a given ecosystem? Fire history Fire history is the study of the chronology of fire events over time, providing detailed information about a forest’s historical fire regime Why is determining historical fire regimes important? • Provides a benchmark by which we can measure change (e.g. estimating the effects of past fire exclusion helps us predict the future) • Can serve as a guide for determining appropriate burn intervals for management plans • Informs designation of desired future conditions, or references for restoration Fire regime classification • The fire regime is a useful concept because it brings a degree of order to a complicated body of knowledge. – Allows for comparisons amongst sites and over time • The science of classifying fire regimes is young (started ~1970s). • There are many ways to define a fire regime; not all systems are consistent with each other. • Descriptions of fire regimes are very general because of fire’s variability over time and space. From Fire Effects on Flora (Brown and Smith 2000). Fire Regime Condition Classes (FRCC) Class Challenge: Use what you know (fire behavior, fuels, plant ecology) to infer the fire regime of this forest How do we determine the details of a historical fire regime ? Gleaning Fire History Information • Historical records or folklore (natives, explorers, settlers) • Photographs, remote sensing – Chronosequence (e.g. LANDSAT) • Paleoecological: Analyzing stratified lake or bog/soil sediments for charcoal; pollen analysis • Vegetation or stand age class distributions (increment cores) • Tree ring records – Dendrochronology Dendrochonology for Fire History • Fires that damage cambium leave a “fire scar” • Fire occurrence is determined by estimating the year of fires based on tree rings and location fire scars. • Can also be used to determine fire intensity, fire seasonality, extent, and associated climatic patterns. • Takes advantage of variability in annual growth rings (complacent vs. sensitive species) • A close-up photograph of an individual tree ring showing the earlywood (larger cells) and latewood (smaller cells), as well as a resin duct (growth is from bottom to top) (photo © LTRR). A diagram showing the tree rings of a "ring porous" tree species, such as oak (Quercus spp.) and elm (Ulmus spp.) (growth is to the right) (photo © LTRR). Close-up photographs of conifer tree rings showing different types and rates of tree growth (photo © LTRR). Fire-scarred incense cedar (Calocedrus decurrens) in Yosemite National Park, CA Fire-scarred ponderosa pine tree (Pinus ponderosa) in the Santa Catalina Mountains north of Tucson, Arizona (photo © H.D. Grissino-Mayer). Seasonality- longleaf pine scar • Sample form Henri GrissinoMayer, Lake Louise, GA What if the tree is dead? Increment cores taken from Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) trees growing on Mt. Graham in southeastern Arizona (photo © H.D. Grissino-Mayer). Cross-Dating • Matching of ring width patterns between specimens used to identify the exact year in which a ring was formed • Useful when no known date is available; ring width patterns in a dead wood sample can be “overlapped” on (live) samples with known dates • Accounts for tree ring anomalies • Extends fire histories back into the past, much further than even the oldest living tree But trees grow at different rates, even in the same stand! • Skeleton Plotting: accounts for the fact “trees in a homogenous stand or forest usually exhibit the same relative pattern of growth variation through time, BUT • Often have absolute growth rates that differ substantially due to living in different microsites” (Laboratory of Tree Ring Research, T. Veblen, AZ) Skeleton Plotting General Procedures • Mark relatively narrow rings on graph paper– the narrower the ring, the taller the line • Match these patterns between samples • Account for missing or false rings • Date your sample • Identify fire years • Create Master Fire Chronology Group 1 Group 2 Example of Master Fire Chronology for ponderosa/Doug-fir forests of Boulder, CO Example application of fire history studies: climate relationships • PIPO Fire history reconstructions show that fires correlated with climate oscillations—wet/dry Niño3 SST (ENSO) A. SW Annual Precip. Superposed Epoch Analysis (SEA) of fire years at Archuleta Mesa SOI (ENSO) B. Four Corners Drought Index (PDSI) (Brown and Wu 2005) Limitations of tree-ring analysis for fire history • Cannot be used in areas without trees, or where trees are killed by fire (Pinyonjuniper woodlands, sand pine scrub)- it will only provide date of last fire • Conservative estimate: Fire scars may be healed-over, some trees might not record a given fire • A large number of samples is required for cross-dating • Sampling is destructive Set of fire scars shown in a section taken from a sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana) growing in California (photo © A.C. Caprio). Limitations, challenges, cont. • The record gets worse the further back in time you go Percent of Trees Scarred (%) Number of Trees 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 1813 1865 1913 1946 % Trees scarred No. of trees 1986 • And the larger the area sampled, the greater number of scars you’ll find (for a while) Results depend on the factors that influence fire behavior– where & how you sample matters! Fire and Lightning Scars Across Topography 80 70 60 50 40 30 Fire Scars Lightning Scars 20 10 0 Ravine Hilltop Knoll Lower Slope Mid Slope Upper Slope Ridgetop • …and does that mean that fires occurred there more frequently, or scarred trees there more often? Some trees scar more easily than others… 60 No. Scars 50 40 PSME 30 PIPO 20 10 0 N E S W …and evidence may be better preserved in certain microenvironments Despite these limitations, fire history data is widely used to characterize fire regimes, and provides the basis for many management frameworks. Additional Applications of Dendrochronology • Ecology: insect outbreaks, forest demographics and growth patterns • Climatology: past droughts or cold periods • Geology: past earthquakes, volcanic eruptions • Anthropology: past construction, habitation, and abandonment of societies • More at the Laboratory of Tree Ring Research, AZ What you will do • Lab Exercise individually • Hand-in by end of class • Extra Credit-- Go to: http://www.ltrr.arizona.edu/skeletonplot/Sk eletonPlot19.htm (review the tutorial) • Do the Crossdating: Skeleton Plot for Yourself exercise CBI- class results 3/25/11