Northern Exposure Introducing US students to Quebec

advertisement

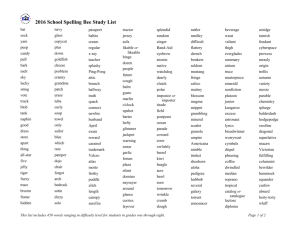

Effects of CALL instruction on high-level, low-frequency English vocabulary Linguistics, CUNY Graduate Center Euna Cho Agenda • Background information on L2 vocabulary knowledge and learning • Methods and procedures of the study • Results and further research suggestions Introduction • Importance of vocabulary learning in L2 language learning, yet teaching is neglected due to the belief in vocabulary learning through extensive reading • Effectiveness in more form-focused, deliberate, intentional teaching in L2 vocabulary acquisition, especially for high-level, low-frequency words shown on the Graduate Record Examination (GRE) • Advantages of Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) instruction in L2 vocabulary teaching Frequent word lists • General Service List (GSL) of English words: 1,964 word families (West, 1953), 80% coverage • New General Service List (NGSL): 2,368 word families (Browne, 2013), 90% coverage • Academic Word List (AWL): 570 word families outside the GSL (Coxhead, 2000) Required number of words • Approx. 3,000 words to engage in a daily conversation (Laufer & Nation, 2011) • 6,000-9,000 words to understand radio interviews or literature (Laufer & Nation, 2011) • 10,000 words to understand 95% of the general texts (Hazenberg & Hulstijn, 1996) • 17,000 words: receptive knowledge of collegeeducated native English speakers (Zechmeister et al., 1995) Frequency of encounters • A learner should see the same word more than 10 times (Laufer & Nation, 2011). • Each new experience with the word should take place before the word is forgotten (Laufer, 2006). • A learner should read 1-2 books per week, which will take 29 years to learn the most frequent 2,000 words (Zahar et al., 2001) Learning vocabulary through reading may not work. Academic words • Receptive knowledge of 17,000 words among collegeeducated native English speakers (Zechmeister et al., 1995) • Learners pursuing higher education should have vocabulary knowledge used in academic contexts. • Moderate use in academic settings; rare in general context (e.g., convoluted, gratuitous, vociferous) • Low-frequency of appearance (Coxhead, 2000) • Form-focused, deliberate, and intentional learning of vocabulary words Vocabulary should be taught! CALL learning environment • Vocabulary is one of the most prevalent applications in a CALL environment. • Multimedia applications: pictorial, audio-visual information in addition to traditional textual cues • Retention is easier and more effective when words are learned in multiple modes (Chun & Plass, 1996). • Multimedia cues yield promising outcomes in L2 vocabulary acquisition (Akbulut, 2007; Al-Seghayer, 2001; Chun & Plass, 1996; Yoshii & Flaitz, 2002) Rationale • Efficacy of computer-mediated multimedia aids shown on beginner and intermediate level vocabulary (Al-Seghayer, 2005; Chun & Plass, 1996; Mohsen & Balakumar, 2011; Yoshii & Flaitz, 2002) • Little attention paid to high-level infrequent words that are important for particular purposes • Advanced-level words are hard to learn, requiring special attention (e.g., multimedia aids) The present study • Efficacy of multimedia cues (video) on advancedlevel English vocabulary shown on the GRE • 15 Korean L1 students preparing for graduate study in the U.S. • Testing 40 unfamiliar words selected from the pre-test (60 items) • Pre-test Definition Treatment (video / text) Post-test 1 (immediate) Post-test 2 (7 days) Post-test 3 (2 weeks) Context of the study • 4 week intensive GRE lecture series in Seoul, South Korea (4 hours X 5 days) in July 2014 • Total enrollment: 27 (9 male, 18 female) recruited from an internet blog • Instruction focused on vocabulary, reading comprehension, and essay writing • Target number of vocabulary: 1,500 GRE words – Etymology, images, videos, and mnemonics Participants • 23 15 for final analysis (6 male and 9 female) • Age: 24-34 (Mean 28, SD 2.94) • Length of residence: 0-10 years (Mean 1.16, SD 2.56) • M-TELP listening (45): 28-42 (Mean 33.8, SD 4.63) • Pre-test results (40): 0-5 (Mean 1.2, SD 1.42) Pre-test (60) • 60 items tested by 24 students (outside 5,000 frequent words) • 40 items below 10% of correctness selected Final test items (40) Pre- and post-tests Treatment • Experimental group (video group) – Dictionary annotations (Korean/English) – Video clips with subtitles • Control group (text group) – Dictionary annotations (Korean/English) – Handout with scripts of the video clips Dictionary annotations Video clips • 40 video clips from movies or TV shows • Edited to show the gist (5-20 seconds) with subtitles • Repeated with synonyms or definition (e.g., pulchritude vs. beauty) • Visually represented with gestures and facial expressions • Played one time with a description or background information Are you and your friends gonna be over here all the time like partying and hanging out? Oh, don’t worry. I am not really a party girl. Wow, don’t just be blurting stuff out. I want you to really think about your answers. From: Friends As you can see, I don’t look like that. That was a moment of useful pulchritude that is long since past. Youthful pulchritude? Don’t ask me what pulchritude means. Pulchritude means beauty. From: Puccini for Beginners King, you’re majesty. I gravel at your feet. It’s not gravel, it’s grovel. From: Lion King Handout for text group Script for the instructor Results Limitations and further research • A small number of participants • Vocabulary size test • Vocabulary learning experience • Participants from diverse language background • More precisely-structured instruction (e.g., recorded instruction) References • Akbulut, Y. (2007). Effects of multimedia annotations on incidental vocabulary learning and reading comprehension of advanced learners of English as a foreign language. Instructional Science, 35(6), 499-517. • Al-Seghayer, K. (2005). The effect of multimedia annotation modes on L2 vocabulary acquisition. Research in Technology and Second Language Education: Developments and Directions, 3, 133. • Browne, C. (2013). The New General Service List: Celebrating 60 years of vocabulary learning. LANGUAGE TEACHER, 37(4), 13. • Chun, D. M., & Plass, J. L. (1996). Effects of multimedia annotations on vocabulary acquisition. The modern language journal, 80(2), 183-198. • Coxhead, A. (2000). A new academic word list. TESOL quarterly, 34(2), 213-238. • Hazenberg, S., & Hulstun, J. H. (1996). Defining a minimal receptive secondlanguage vocabulary for non-native university students: An empirical investigation. Applied linguistics, 17(2), 145-163. References • Laufer, B. (2006). Comparing focus on form and focus on formS in second-language vocabulary learning. Canadian Modern Language Review/La Revue canadienne des langues vivantes, 63(1), 149-166. • Laufer, B., & Nation, I.S.P. (2011). Vocabulary. In S. Gass & A. Mackey (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition (pp. 163-176). London and New York: Routledge. • Mohsen, M. A., & Balakumar, M. (2011). A review of multimedia glosses and their effects on L2 vocabulary acquisition in CALL literature. ReCALL, 23(2), 135-159. • West, M. (1953). A General Service List of English Words. London: Longman, Green and Co. • Yoshii, M., & Flaitz, J. (2002). Second language incidental vocabulary retention: The effect of text and picture annotation types. CALICO journal, 20(1), 33-58. • Zahar, R., Cobb, T., & Spada, N. (2001). Acquiring vocabulary through reading: Effects of frequency and contextual richness. Canadian Modern Language Review/La Revue canadienne des langues vivantes, 57(4), 541-572. • Zechmeister, E. B., Chronis, A. M., Cull, W. L., D'Anna, C. A., & Healy, N. A. (1995). Growth of a functionally important lexicon. Journal of Literacy Research, 27(2), 201-212. Thank you! CUNY Graduate Center Euna Cho (echo@gc.cuny.edu)