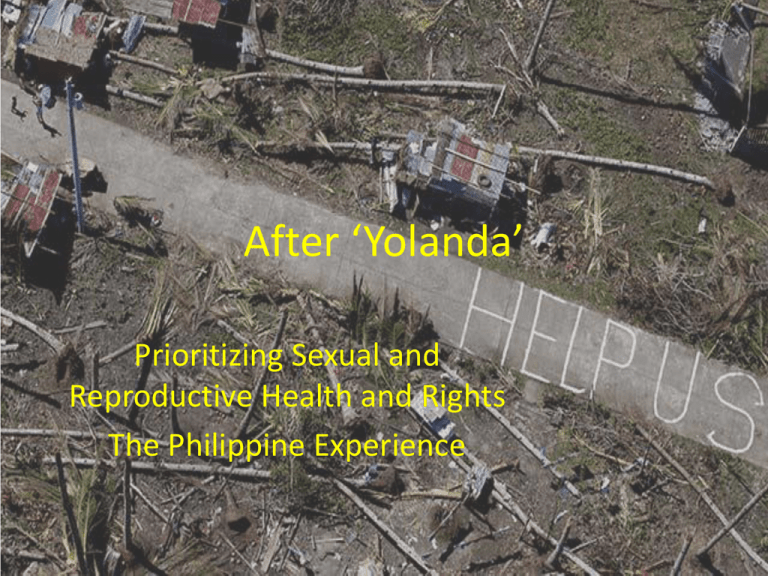

After ‘Yolanda’

Prioritizing Sexual and

Reproductive Health and Rights

The Philippine Experience

Before ‘Yolanda’

• Poverty, landlessness and sexual exploitation were already major

social and economic problems for the people of Eastern Visayas,

which was considered the third poorest in the Philippines (Oxfam

assessment)

•

Situation was exacerbated by weak infrastructure and struggling

agricultural and fishing sectors, with almost two million people

earning less than $2 per day,

• Women were especially vulnerable. “Eastern Visayas is known as a

source of women and children for sexual exploitation, and men and

boys for labor exploitation. This is primarily due to the high poverty

incidence in the region.” (IOM’s National Project Development Officer

Romina Sta. Clara.)

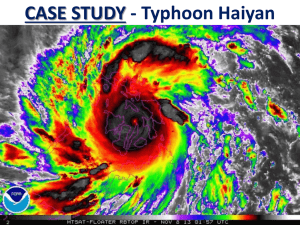

When Yolanda struck

When news of the “Super Typhoon” emerged, the national

government immediately issued a warning to all areas

under threat, with President Aquino even launching an

unprecedented national televised address warning the

people about the coming disaster

Some national officials (including the defense and local

government chiefs) were deployed to Leyte to oversee the

preparations and response to the typhoon

When Yolanda struck

• As Yolanda approached the Philippines, approximately 800,000 people

were evacuated and disaster response personnel and equipment were

quickly deployed. Such immediate action by the authorities, say aid

agencies and local responders helped save many lives and facilitated the

subsequent relief effort.

• Yolanda was the strongest

typhoon to make landfall ever

recorded, with wind speeds of 315

kph (195 mph). The accompanying

storm surge sent a wave up to five

metres high smashing through

coastal communities, killing many

who thought they were safe.

After Yolanda

• Shortly after the disaster, the government estimated

that more than 2.1 million families were affected by

Yolanda, equivalent to around 9.53 million individuals

(DSWD), with majority found in Leyte and Samar, but

also Aklan, Iloilo, Palawan, Bohol and Bicol

• Some months later, in an assessment, Oxfam put the

number of affected individuals at a much-higher 15

million, with at least 5,600 killed and over 26, 200

injured

• Over four million are still displaced from their

homes,with 1.2 million homes damaged or destroyed

After Yolanda

• DSWD also estimates some 96,039 displaced families with

449,416 individuals staying in 1,790 evacuation centers. Some

36,600 other families composed of 182,379 individuals have

sought shelter in homes of friends and relatives.

• Among those affected by the typhoon were front-liners like

police and soldiers, social workers, medical and rescue

personnel, with the local governments in affected areas

practically paralyzed

• Lack of power and communication facilities hampered

immediate rescue and relief efforts

Response to Yolanda

Outpouring of relief and

assistance from both the national

government and foreign

governments

UN designated its disaster

response an “L3” – its highest

classification, with UN emergency

response team reaching Tacloban

within 12 hours of Yolanda striking

land

• At the request of the business community, whose establishments had

been subjected to looting by survivors, among the first personnel to be

brought to Leyte and Samar were police and soldiers for peacekeeping

duties, with personnel from the Department of Health, the Department of

Social Welfare and Development and other agencies closely following

Response

• More support mobilized by international organizations

and agencies, including the Red Cross, IOM, Fuel for

Relief Fund and thousands of individual donors

• So far, an estimated three million people have received

food assistance including rice, high energy biscuits and

emergency food items

More than 35,000 households received tarpaulin sheets

or tents (particularly in Eastern Samar and Leyte

provinces) with efforts to reach another 478,000

households under way

Response

• About 80 per cent of people still in Tacloban City

had access to clean water and about 60,000

hygiene kits had been distributed.

• This and other aid – including health care,

services to protect children, and cash transfers –

have helped keep families alive, prevented

outbreaks of disease, and begun to help people

to rebuild their lives.

• In the context of Yolanda’s severity and the

logistical challenges it created, these are notable

successes. (Oxfam assessment)

Reproductive Health Issues

• DSWD counts 233,697 pregnant women affected by

the typhoon and requiring specialized reproductive

health services. In evacuation centers alone where the

displaced are temporarily housed, a total of 7,973

pregnant women had been counted as of late last year.

• “The biggest challenge is really the continuation of

maternal healthcare services. With so many health

centres destroyed, women have no place to go for their

pre-natal examinations. Midwives will have to go find

the pregnant women, but often the midwives are also

among the affected population.” (Amelita Robles, provincial health

officer)

Repro Health

• -- Health experts fear conditions in evacuation centers can

put pregnant women at heightened risk of malnutrition and

pre-term labour. “In the centers, she is dependent on food

rations, which are usually rice and canned goods. These will

not provide the necessary nutrients that a pregnant woman

needs” (UNFPA officer)

• Malnutrition in pregnant women can also increase the

chances that their babies will be sick, or die.

• The psychological trauma of a disaster on the scale of

Yolanda may bring on premature labor, say health workers,

and if the baby is delivered pre-term, there is a lower rate

of survival

Repro Health

• The needs of pregnant women from [confirmation of] pregnancy

to… giving birth need to be integrated into emergency and relief

response (FPOP)

• Of the 14.4 million affected people, 25% are women who are of

reproductive age, which is equivalent to 3.6 million (IPPF)

• This serves to indicate the

large number of women

who could get pregnant by

their spouses as people still

have sexual intercourse

even in times of crisis. There

are also cases of unplanned

pregnancies especially when

contraception is not used,

or when a girl or woman is

raped.” (IPPF)

Repro Health

An estimated 900 babies are born daily in the typhoon-hit

regions. But with limited access to medical facilities and aid,

newborns are exposed to the risk of respiratory complications

and infections, and mothers to childbirth complications and

obstructed labor that can result in death.

• Yet these deaths are mostly preventable if a basic and

sterile delivery kit is available. A simple cloth can help

warm the baby against developing cold or hypothermia,

while clean gloves can be used to contract a mother’s

uterus to prevent excessive bleeding post delivery.

Minimum Package

•

These life-saving items are often taken for granted

until times of emergency, amid chaos and ruins, when

we realize they are not readily accessible. Even a clean

blade makes a difference in ensuring the umbilical cord

is cut without an infection hazard.

• Under the internationally approved Minimum Initial

Service Package (MISP) for reproductive health, certain

activities must be implemented at the onset of every

emergency, including distributing emergency delivery

kits to displaced pregnant women in their last

trimester. The emergency kits for women and

traditional birth attendants to aid safe delivery may

contain a plastic sheet, a razor blade and a bar of soap.

Ongoing challenge

• Sexual and reproductive health service is one area that

hasn’t been adequately recognized by humanitarian

responders and communities on the ground. In the

Philippines, it remains an ongoing challenge, as access to

reproductive health rights is often faced with opposition

due to religious and cultural sensitivities.

• The 2011 Family Planning Survey noted that the country’s

maternal mortality ratio jumped by 35 percent, from 162

deaths per 100,000 live births in 2006, to 221 in 2011. And

still, the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health

Law is still undergoing deliberations in the Supreme Court

VAW and trafficking

• In emergencies, desperation drives families to seek

alternative sources of income, and adolescent girls and

women may have to engage in transactional sex or fall

prey to human trafficking (Save the Children)

• Domestic violence is also likely to increase as

frustration grows within the family unit and women

and girls bear the brunt.

• Of the millions of people affected by the typhoon, an

estimated 56,400 women between 15 and 49 years old

are at risk of sexual violence. In the evacuation centers,

around 2,500 women are at risk.

Facilities for women

• UNFPA-organized reproductive health medical

missions

• Creation of at least 17

‘women-friendly’ spaces,

providing information

sessions on the

prevention of genderbased violence and

psychological counseling

• “Women’s gardens” in

Samar

Disadvantages

• On top of the increased risk for gender-based violence,

women who lost their husbands to disasters may find it

difficult to retrieve property, receive compensation for

destroyed homes or gain access to loans because

family property is usually in their husband’s name.

There is also a consensus that women are less likely to

survive disasters, and that planning and warning systems

need to be responsive to this reality. Women and girls are

less likely to know how to swim and have less upper body

strength required to hold on to trees or other anchors

(Ferris)

Trafficking

• Currently, local government units and social

workers have been alerted regarding the

possibility of trafficking of children in Yolanda

areas, whether for sex trafficking or forced

labor, and are coordinating with national

agencies

• Need for better coordination regarding

policies, programs and actions on the welfare

of Yolanda orphans (New York Times story)

What needs to be done

•

For the Philippine government:

•

Ensure that services to protect vulnerable groups, such as

women and children (and elderly), are rapidly expanded. These

should include access to trained protection staff and domestic

violence telephone hotlines; increased deployment of female

police; and women-friendly spaces in displaced communities.

•

All of these steps should be supported as a crucial part of the crisis

response and not as a secondary issue (alongside of course

measures to ensure ‘safe programming’, so that no part of the

response increases risks for women, girls or other vulnerable

groups).

What needs to be done

• By the Philippine government

• Deliver a pro-poor reconstruction strategy that

spearheads a major economic development of

the worst affected regions and tackles

inequalities, including gender, that make people

vulnerable.

• The strategy should involve communities

(including women’s groups) in the design and

implementation of structures, especially

residences

For UN and Int’l NGOs

• Continue to increase support to the Philippine

government and state institutions, as well as civil

society organizations, in order to accelerate the

response and ensure sustainability of the

recovery and reconstruction efforts.

• International actors should integrate their

activities with those of domestic actors, avoiding

the establishment of parallel service provision

and uncoordinated investments.

UN and int’l NGO’s

• Strengthen gender analysis across all programs

and implement projects accountably and on the

basis of the needs and priorities of different

groups.

• This should include actively supporting women’s

leadership and women’s organizations, and

looking for other opportunities to ensure that

relief and recovery programs help to promote

gender equality in the long-term. (Source: Oxfam assessment)