Pub.policy221.winter.11.wk3

advertisement

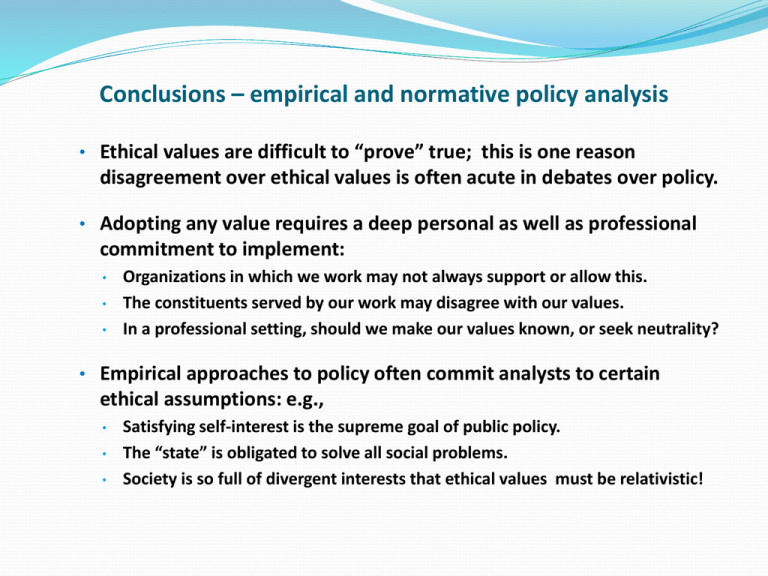

Conclusions – empirical and normative policy analysis • Ethical values are difficult to “prove” true; this is one reason disagreement over ethical values is often acute in debates over policy. • Adopting any value requires a deep personal as well as professional commitment to implement: • • • Organizations in which we work may not always support or allow this. The constituents served by our work may disagree with our values. In a professional setting, should we make our values known, or seek neutrality? • Empirical approaches to policy often commit analysts to certain ethical assumptions: e.g., • • • Satisfying self-interest is the supreme goal of public policy. The “state” is obligated to solve all social problems. Society is so full of divergent interests that ethical values must be relativistic! Public Policy and Democracy Democracy as a factor in public policy – divergent theories: Political approach – democracy is a set of political institutions that permit people to make many choices, as opposed to a few (e.g., Pal and Weaver); and which also permits means for compromise and satisfying many interests. Economic development approaches – democracies are polities that promote production of public goods which, it turn, helps fulfill the needs of many as opposed to only a few (e.g., Feng, et. al). Cultural approaches – democracies are based on certain cultural practices that promote openness, fair play, rule of law, majority rule, and respect for minority rights (e.g., Barro). These include civility, tolerance, diversity. Why do these various approaches matter? There is good empirical evidence that democracies embrace a wider range of public policies for more citizens than do authoritarian systems: More ways for citizens to make demands on system. More opportunities for peaceful change and influence on policy-making. Greater freedom for an independent civil society to exist (i.e., non- governmental groups that lie between the individual and the state such as media, interest groups). However, different approaches to democracy offer divergent reasons why some public policies are successful while others are not: (Political) can institutions overcome political impasse and obstruction? (Economic) doe polities have sufficient resources to address problems? (Cultural) do prevailing values favor the rule of law and peaceful change? Political approaches to democracy & public policy Structural/functional approach – posits that there are activities common to all polities which permit comparing policy-making processes. Structures are unique. Interest articulation – done by formal interest groups that act to influence policy: Lobby legislatures. Ally themselves with political parties to contest elections. Interest aggregation – melding interests together into broad-based electoral coalitions Political parties - purpose is primarily to contest elections and control legislative votes. Rule-making – done by legislatures; in more developed polities undertaken at ‘redundant levels’ depending on the policy area (i.e., federalism). Rule implementation – performed by executives and appointed bureaucracies. Rule adjudication – performed by judiciary, some regulatory agencies In developed systems, courts are independent of the policy- making and implementation. Structural-functionalism & public-policy process POLICY MAKING (Rule-making) & IMPLEMENTATION AGENDA SETTING Interest articulation Interest groups Other civil society entities: -Media -Churches -Voluntary organizations Interest aggregation Political parties: assemble group demands Seek to electorally control legislatures – - legislative control in parliamentary systems = Control of executive & of policy execution/ enforcement by bureaucracy Regional/state/local levels Civil society RULE ADJUDICATION National Level Redundancy of function – but for more specialized activities (e.g., K-12 education, law enforcement; urban planning) Courts/specialized regulatory bodies: - Independent - Less independent Challenges to political approaches – implications Interest articulation may be performed by freely-operating voluntary associations (interest groups) or by state-controlled organs such as a centralized policy apparatus (e.g., China, former Soviet Union). Despite nominal differences – even in authoritarian systems group goals are articulated; usually informally, through “mutually beneficial networks” and personal contacts. Civil society remains weak and ineffective, power must be exercised discretely. The more developed a polity, the more complex the structural array of institutions bearing on their development and implementation. Significance? Policies are more flexible: they are designed from the beginning to be amendable in response to new information, changing conditions (e.g., student aid programs in the U.S. – so many institutions and actors have a hand in their design that these programs have evolved to serve the needs of students, parents, colleges and universities, and even lending institutions). Economic approaches to democracy & public policy Basic goal of every polity is to generate wealth through managing the economy – essential avenue for satisfying human needs. Theoretical claim: a growing, vibrant economy results in: Greater levels of prosperity. Higher-levels of education and personal achievement. Greater political stability & tolerance. More opportunities for equity (i.e., larger middle class, less poverty, higher GDP per capita). Increased infrastructure investment – larger & better planned cities. Over time, a cleaner & healthier environment: Pollution increases at early stages of prosperity but decreases when: per capita income levels and export-driven growth rise; middle class expands – leads to demands for improved quality of life (CSAB-Washington University, others). Shanghai, China – one of the world’s largest cities, busiest port, & financial center of the Pacific Rim Mumbai – India’s largest city (15 million+) has a central role in country’s banking, manufacturing, and Internet –related economies Challenges to economic approaches – implications As wealth is generated, public expects even better performance (i.e., “revolution of rising expectations” – T. Gurr, R. Abeles): how can this be managed? If disparities of wealth become pronounced, political polarization may arise, as well as political violence, inability to compromise (e.g., Feng). Contrary to widespread belief, wealth does not dissipate traditional values (e.g., tribalism, ascriptive values and practices – instead they become grafted onto modern practices: so-called “modernization of tradition” (L. and S. Rudolph): Interest groups and political parties are formed around castes, tribes, religious beliefs. Policy debates surrounding, e.g., education, jobs, health care, welfare programs often divide along traditional group relationships – seen in Sub-Saharan Africa, S. Asia. Political friction often arises between traditional groups who contest “modern” benefits: resource allocation, economic investments, patronage. Cultural approaches to public policy & democracy Key question: what is the role of underlying values and attitudes on democratic policy-making: – e.g., why do some societies support a role for the state in certain policy areas (e.g., health care) and others are reluctant to do so? Civic capital theory (Barro, J. Mansbridge, R. Putnam): largest influence on policymaking is the propensity of citizens to join groups, participate in civic life, donate time/money to causes. Participation generates a sense of public spiritedness. Public spiritedness – political equivalent of altruism; distinguished from private spiritedness – i.e., resistance to pulling together for a common good: Public spiritedness accounts for many policy debates over civil rights & liberties, anti-war movements, anti-poverty programs, community empowerment policies – these cannot be explained as mere self-interest or calculated personal gain. Private spiritedness, by contrast, is corrosive – leads to resistance to sacrifice for greater good; tendency to blame one’s misfortune on the “greed” or self-interest of others. Challenges to cultural approaches – implications There may be political or economic impediments to civic capital: Resistance to joining groups/legacy of communism (e.g., Russia and Eastern Europe). State insistence on regulating/“licensing” civil society groups. Disparities of wealth, coupled with disinclination to contribute to groups. Public spiritedness is facilitated by “deliberative bodies” or small group settings; e.g., workplace decision-making, community action groups, etc. In many developing countries, there is political resistance to decentralization. In many developed/developing societies, there is bureaucratic resistance to consultation. Is culture an independent or dependent variable? Cultural values receptive to democracy may be influenced by economic conditions or institutional reform – progress in resolving political and economic impediments may affect cultural values.