Slides - Competition Policy International

advertisement

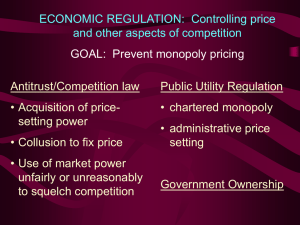

ANTITRUST ECONOMICS 2013 David S. Evans University of Chicago, Global Economics Group TOPIC 14: Date Elisa Mariscal CIDE, Global Economics Group VERTICAL RESTRAINTS Topic 14| Part 1 14 November 2013 Overview 2 Part 1 Part 2 Vertical Restraints Overview DoubleMarginalization Single-Monopoly Profit Theorem Procompetitive VR Justifications Procompetitive Tying Theories Anticompetitive VR Theories Anticompetitive Tying Theories 3 Vertical Restraints Overview Vertical Restraints Impose Conditions on the Actions of the Buyer or Seller 4 Vertical restraints may be imposed. • by the seller on the buyer or by the buyer (e.g. tying). • by the buyer on the seller (e.g. lowest price guarantee) . • or they may be result of negotiations between the buyer and the seller and included in the contract between them. They may reduce transactions costs between the buyer and seller (procompetitive) but they could also limit competition (anticompetitive). Common Vertical Restraints Considered by Competition Policy 5 Tying and bundling: seller provides one product on condition buyer take another product (tying) or seller provides separate products only as a bundle (bundling). Exclusive dealing: seller provides product only if buyer does not also buy from rival. Conditional rebates: price incentives conditional upon purchasing across multiple products. Most favored nation: seller guarantees lowest price or agrees to meet competitor’s price. Resale price maintenance: seller limits price buyer can resell at. Vertical Restraints Can Involve Downstream Firm or Final Customer 6 Vertical restraints between seller and final consumer (which could be person or business). • Telco requires purchase of both voice and Internet. • Computer manufacturer requires purchase of computer and service contract. Vertical restraints between seller and downstream firm. • Seller limits actions of reseller through for example resale price maintenance. Vertical Restraints can Involve Sale by Upstream Firm to Downstream Firm 7 Firms are often part of a vertical chain of production and distribution. Upstream An upstream firm (Kellogg’s) might sell its product (Cornflakes) to a downstream retailer (Tescos) which it sells onto consumers. Manufacturer Retailer Downstream Firms often outsource inputs. For example, Ford buys motor parts from other companies, then sells them to dealers who sell to consumers. Consumers Key Competition Policy Issues 8 Modern competitive policy recognizes that vertical restraints solve transaction cost problems and increase efficiency, but Vertical restraints could be used by firms with significant market power to harm consumers, although The single-monopoly profit theorem shows that dominant firms may not have the incentive to do so in some (perhaps many) circumstances. So we have to compete up with rules and analyses to distinguish anticompetitive from procompetitive vertical restraints. 9 Single-Monopoly Profit Theorem The Chicago Single Monopoly Profit Theorem 10 Key assumption for theorem •Tying product and the tied product are consumed in fixed proportions such as car and air conditioning. •A firm has a monopoly in the tying market. •The market for the tied product is perfectly competitive. Chicago Single Monopoly Profit Theorem •A monopoly in the tying product can’t increase its profit by obtaining a monopoly in the tied product. It is already making as much as it can from the two products. Explanation •Consumers buy the products as a system and have a maximum amount they are willing to pay for the system. That leads to a single profit-maximizing price for the system. If the tied product is supplied competitively it doesn’t make any difference whether the monopolist supplies it and bears to the cost or lets a competitive firm supply it at cost to consumers. Incentives to foreclose •Firms could could have an incentive to foreclose only if the tying and tied products are consumed in variable proportions such as photocopies and ink cartridges. © Global Economics Group. Do Not Distribute Without Permission 10 Illustration of Single-Monopoly Profit Theorem 11 Component A and B are used together (fixed proportions) Firm has monopoly on A Consumers willing pay by $10 for A+B Assume cost of A and B are both $1 per unit The most the monopolist can get is $10 and earn a profit of $8. • $10 for AB; • $9 for A and $1 for B (with B provided separately) • $(10-p) for A and $p for B (with both provided together) • $9 for A and allows competitive industry to supply B for $1 11 Monopolist in A’s Best Strategy is to Enable Consumers to Get Product B at Lowest Cost 12 Component A and B are used together (fixed proportions). Firm has monopoly on A. Consumers willing pay by $10 for AB. Assume MC of A is $1. Assume MC of B is $3 for monopolist and $2 for a competitive industry. The the monopolist’s profit maximizing strategy is: Sell A for $8 and encourage a competitive industry which supplies B for $2. Generally, if another firm could produce a component at a lower cost than the monopolist the monopolist has an incentive to have that firm produce. Hilti AG v. EC Commission 13 Hilti made nail guns. Hilti had a patent on cartridges for its nail guns. Cartridges and nails were used in fixed proportions. Hilti required customers who bought its cartridges to also buy its nails. Commission found Hilti guilty of tying abuse and CFI and ECJ affirmed. Single monopoly profit theorem shows no apparent possibility of additional monopoly profit here from leveraging. Are there any other possible theories of harm?. 14 Single Monopoly Profit Theorem Not Necessarily True if Variable Proportions Single monopoly profit theorem true only if there are fixed proportions. If the purchases of goods A and B are in variable proportions then the theorem does not establish impossibility of second profit. When the theorem does not hold it is possible that a firm could leverage monopoly from product A to B and earn more profit. Classic example is from Whinston who shows that it is possible that there is a second monopoly profit if: • Products A and B consumed in variable proportions. • Incumbent monopolist produces A and B. • Competitive entrant produces B. • Scale economies in the provision of B. • Tying A to B excludes B if enough consumers want to consume A together with B. 15 Tying 16 “Tying” Involves Only Selling One Product with Another Product Contract: You must buy Product A to get Product B. Technology: You can only get Product B integrated together with Product A. Price: You can get Product B much cheaper if you buy Product A. In each case the firm is limiting the ability of the consumer to choose the “tying good” (A) without getting the “tied good” (B) too. 17 European Commission Case Against Microsoft Classic Tying Case Microsoft provided Windows Media Player (“WMP”) as a part of Windows. Commission complained that Microsoft was dominant in operating systems Windows and tied a media player (WMP) to its dominant operating system and that this was an abuse of Article 101 (then 81) TFEU. Microsoft said that Windows Media Player was a feature of Windows and really just one integrated product and consumers wanted it that way. Commission remedy was to require Microsoft to offer consumers a version of Windows without WMP in addition to a version with WMP so consumers would have choice. Virtually no one licensed the version of Windows without its media player. Overview 18 Tying in Practice. Tying for Efficiency. Tying for Price Discrimination. Tying for Exclusion of Competitors. Rule of Reason vs. Per Se Analysis. Some Common Examples of Tying 19 Mobile phones: • Operating system. • Camera. • Alarm clock. Shoes: • Shoes. • Laces. • Polish. Cars: • Tires. • Air conditioning. • Radio. Checking account: • Checks. • Debit card. • Deposit account. Product Design and Bundles 20 Basic product design questions for firms: • What features should the firm provide or leave to other firms?. • What “features” would some consumers like to purchase together?. • Are there enough consumers who want that combination to make it profitable to provide?. Answering these questions determines: • How many different products the firm offers. • The features that those products have. Better Products for Consumers 21 Reduces transactions costs of buying separate products (e.g. sports news and local news). Pays producer to make choices for the consumer (e.g., hospital hires the anesthesiologist). Enables products to work better together (e.g., camera and email on phone). Reduces search costs by preselecting choices. Less Costly Products for Firms 22 Offering product involves fixed costs of packaging, stocking and tracking (e.g. pain relievers plus decongestants). By combining features reduces fixed costs (e.g. one distributor for sports new and local news and everything else in newspaper). Can average fixed costs across potentially more consumers who want it. Tying Complementary Products 23 Consumers often want to consume two products together: • Razors and blades. • Shoes and shoelaces. • Operating systems and browsers, media players, etc. Seller saves consumer time by providing together: • Consumers don’t need to make separate purchase. • Benefit from technical integration. • Reduce packaging costs. Aggregating Demand and Cost Reductions 24 Many products similar to supermarkets: • No one buys all possible products. • Supermarket selects products so most consumers can find what they want. • Maximizes profit from fixed store space and staff. Newspapers are like supermarkets: • No one reads all stories or sections. • Newspaper selects content so most readers can find enough value. • Maximizes number of consumers for fixed product cost of newspaper. Similar products include many information goods: • Software (no one uses all features of spreadsheets). • Web portals (no one uses all features). Metering Demand for Durable Good 25 Applies to durable good used with consumable good (like photocopier and ink cartridges). Objective is to charge more to people who use the durable good more—to engage in price discrimination. Require customers to use manufacture-supplied “consumable” and set pricing schedule for consumable so consumers who value it most pay highest total price . Examples include photocopies and ink cartridge; nail guns and nails; automobiles and parts. Bundling to Get More Consumer Surplus 26 “Block Booking Example” from Nobel Prize Winner George Stigler Theatre 1 Movie Offering Theatre 2 Maximum Price Theatre Will Pay Optimal Price Profit Consumer Surplus Gone with the Wind $8000 $7000 $7000 $14000 1000 Gertie’s Garter $2500 $3000 $2500 $5000 500 $10500 $10000 $10000 $20000 500 +1000 -1000 Bundle Change from Bundling Cost per Movie 0 NOTE: Total surplus is unchanged--producers get +1000 and consumers -1000. © Global Economics Group. Do Not Distribute Without Permission Extending Monopoly Into Secondary Market: Example 1 27 Consider monopoly hotel (for tourists) and local tennis club (for tourists and locals) on island. Hotel engages in strategy to extend its hotel monopoly to tennis clubs. Hotel starts a tennis club and ties it into staying at hotel. Incremental cost to guest of using hotel club is zero (or low). Local tennis club loses enough customers that it can’t support overhead. Locals must go to hotel tennis club too and so the hotel ends up with a monopoly. 28 Preventing Entry into Primary Monopoly: Example 2 Monopoly software platform provider and browser supplier. Suppose browser could evolve into a platform. Monopoly invests in leveraging into browser to eliminate competition there. Monopoly software platform ties its own browser to its platform. Third party browser loses customers because people don’t both installing another browser since they already have one. Potential entrant into software platforms is eliminated. Critical Question: Does Firm Have Incentive and Ability to Foreclose? 29 Can the firm earn extra profits by tying—this could provide an incentive?. • Could it make more money by obtaining a monopoly in the tied market?. • Note that tying isn’t costless since if consumers prefer not to buy the tied good from monopolist it reduces the demand and revenue for the monopolist. • Could it avoid losing money from having its monopoly in the primary market eroded?. Does the firm have the ability to foreclose?. • Does it have enough market power to dictate choices to consumers and foreclose enough demand from the firm in the secondary market?. • Can it dissuade other firms from entering the secondary market?. 29 The Ability to Foreclose Rivals Is Limited 30 Tying Must Drive Competitor in Tied Product Out. • To earn extra profit when tying and tied product are consumed in variable proportions the producer of the tying product must be able to drive the producer of the tied market out and preserve the market for itself. • Most plausible if there are scale economies in tied product and diversion of sales to tying firm makes it impossible for the tied firm to attain sufficient scale. Tied Firm Must Not Have Counter-Strategy. • Target could lower its price to outlast the monopoly. • Target could leverage into tying market. 30 Evolution of Tying From Very Bad to Usually Good 31 Per se violation in US starting with International Salt in 1947. Viewed as almost always bad. But Supreme Court has moved away gradually starting with Jefferson Parish (1984) and Illinois Tool Works (2006). Recognizes tying is usually good. Per se abuse under Article 101 TFEU (see Hilti (1991), TetraPak (1994), and Microsoft (2007)). But European Commission now treats tying more or less under rule of reason for enforcement priorities— tying bad only if it results in significant market foreclosure. While professional consensus is that tying is seldom anticompetitive US and EU courts still have discretion to treat it as a per se abuse without doing a deeper analysis. Per Se Approach Could Prevent Good Tying 32 Prohibition of tying by dominant firm could prevent it from engaging in tying that increases consumer value or reduces costs. Therefore need a sharper test that can allow good tying to continue but condemn bad tying when it is tried. Rule of reason analysis allows court to consider procompetitive features of tying as well as anticompetitive possibilities and balance the two. Recommended Rule of Reason Approach 33 Does firm have significant market power?. • If it doesn’t it can’t force consumers to take tied product. • If it doesn’t it can’t foreclose rivals from tied market. Is it plausible the tying strategy could be anticompetitive?. • Unlikely if there are fixed proportions. Unlikely if there are no scale economies in secondary market. If both answers are yes compare procompetitive and anticompetitive effects. • Examine whether it has or could likely foreclose competition and thereby raise prices. Examine whether there are procompetitive benefits such as higher quality for consumers or lower prices?. Condemn only if bad outweighs the good. 33 End of Part 1, Next Class Part 2 34 Part 1 Part 2 Vertical Restraints Overview DoubleMarginalization Single-Monopoly Profit Theorem Procompetitive VR Justifications Procompetitive Tying Theories Anticompetitive VR Theories Anticompetitive Tying Theories