ITL Research 2011 Fi..

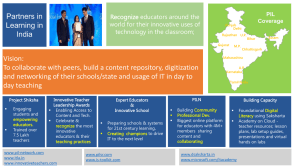

advertisement