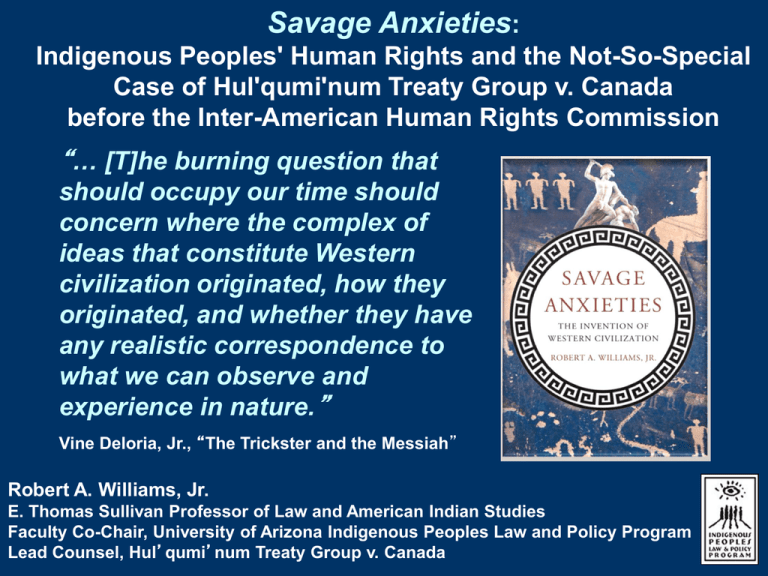

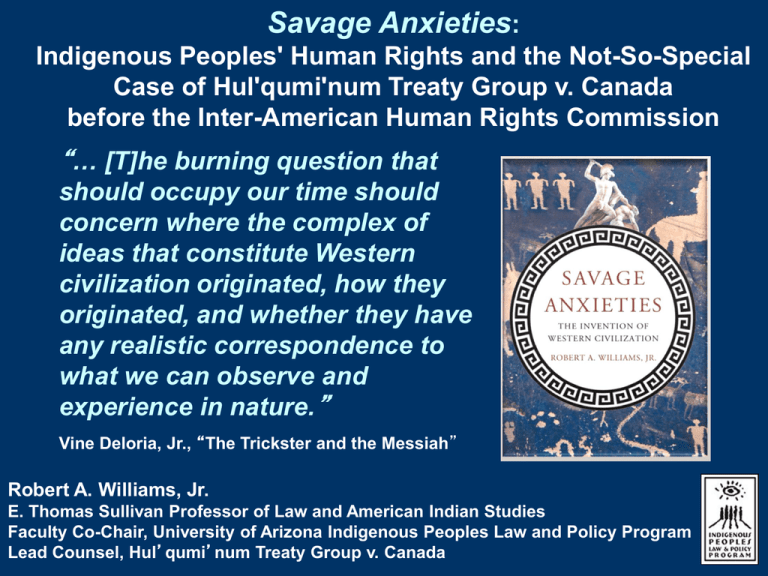

Savage Anxieties:

Indigenous Peoples' Human Rights and the Not-So-Special

Case of Hul'qumi'num Treaty Group v. Canada

before the Inter-American Human Rights Commission

“… [T]he burning question that

should occupy our time should

concern where the complex of

ideas that constitute Western

civilization originated, how they

originated, and whether they have

any realistic correspondence to

what we can observe and

experience in nature.”

Vine Deloria, Jr., “The Trickster and the Messiah”

Robert A. Williams, Jr.

E. Thomas Sullivan Professor of Law and American Indian Studies

Faculty Co-Chair, University of Arizona Indigenous Peoples Law and Policy Program

Lead Counsel, Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group v. Canada

The European Colonial Era Doctrine of Discovery and

Indigenous Peoples’ Human Rights

The First Charter of Virginia

(issued by King James I, April 10, 1606)

“...We, greatly commending, and

graciously accepting of, their

Desires for the Furtherance of so

noble a Work, which may, by the

Providence of Almighty God,

hereafter tend to the Glory of his

Divine Majesty, in propagating of

Christian Religion to such People,

as yet live in Darkness and

miserable Ignorance of the true

Knowledge and Worship of God, and

may in time bring the Infidels and

Savages, living in those parts, to

human Civility, and to a settled and

quiet Government: Do, by these our

Letters Patents, graciously accept of,

and agree to, their humble and wellintended Desires…”

Johnson v. McIntosh (1823)*

CHIEF JUSTICE MARSHALL:

“…On the discovery of this immense continent, the

John Marshall

great nations of Europe were eager to appropriate to

themselves so much of it as they could respectively

acquire. Its vast extent offered an ample field to the

ambition and enterprise of all; and the character and

religion of its inhabitants afforded an apology for

considering them as a people over whom the superior

genius of Europe might claim an ascendancy.… But, as

they were all in pursuit of nearly the same object, it was

necessary, in order to avoid conflicting settlements,

and consequent war with each other, to establish a

principle... This principle was, that discovery gave title

to the government by whose subjects, or by whose

authority, it was made, against all other European

governments, which title might be consummated by

possession.”

*A computer search reveals that up to forty-four Canadian cases

have cited Johnson v. M’Intosh.

R. v. Syliboy (1929)

1 D.L.R. 307 (Canada)

“…But the Indians were never regarded as an independent

power. A civilized nation first discovering a country of

uncivilized people or savages held such country as its

own until such time as by treaty it was transferred to some

other civilized nation. The savages’ rights of sovereignty,

even of ownership, were not recognized. Nova Scotia had

passed to great Britain not by gift or purchase or even by

conquest of the Indians but by treaty with France, which

had acquired it by priority of discovery and ancient

possession, and the Indians passed with it….”

William v. British Columbia (The Tsilhqot’in Case)

2012 BCCA 285

“The basic concepts underlying claims of Aboriginal title and

Aboriginal rights are straightforward. First Nations occupied the

land that became Canada long before the arrival of Europeans.

…European explorers considered that by virtue of the “principle

of discovery” they were at liberty to claim territory in North

America on behalf of their sovereigns (see Guerin v. The Queen,

[1984] 2 S.C.R. 335 at 378). While it is difficult to rationalize that

view from a modern perspective, the history is clear. As was said

in Sparrow :

[W]hile British policy towards the native population was

based on respect for their right to occupy their

traditional lands, … there was from the outset never any

doubt that sovereignty and legislative power, and indeed

the underlying title, to such lands vested in the Crown;

[see Johnson v. M'Intosh (1823), see also the Royal

Proclamation itself ; Calder …]”

Ancient Greek Colonization of the Barbarian World

Western Civilization and the Language of Savagery:

“We sailed hence, always in much

distress, till we came to the land of

the lawless and inhuman Cyclopes.

Now the Cyclopes neither plant nor

plow, but trust in providence, and

live on such wheat, barley, and

grapes as grow wild without any

kind of tillage, and their wild grapes

yield them wine as the sun and rain

may grow them. They have no laws

or assemblies of the people, but

live in caves on the tops of

mountains; each is lord and master

in his family, and they take no

account of their neighbors.”

Homer, The Odyssey, Book IX

Aristotle’s Theory of Natural Slavery

“…Wherefore the poets say, It is

Aristotle

(384 BC–322 BC)

meet that Hellenes should rule

over barbarians; as if they thought

that the barbarian and the slave

were by nature one…

…Wherefore Hellenes do not like

to call Hellenes slaves, but

confine the term to barbarians.

Yet, in using this language, they

really mean the natural slave of

whom we spoke at first; for it

must be admitted that some are

slaves everywhere, others

nowhere…”

The Roman Empire and the Barbarian World

Imperial Rome and the Language of Savagery

“They were wild, savage and warlike, tribes which no one who

has ever lived would not wish to see crushed and subdued.”

Cicero, 1st Century B.C.

Western Civilization’s Wars against the Savage

• Charlemagne’s Wars against

Tribes of Europe

• The Christian Crusades to the

Holy Lands

• The Teutonic Knights and Pagan

Lithuanians

• The Papal Bull Laudabiliter and

the “Wild Irish”

• The Spanish Reconquista

• Inquisition, Expulsion of Jews

• Romanus Pontifex and the Papal

Donation of Africa

• Inter Caetera and the Papal

Donation of the New World

Calvin’s Case (1608)

LORD EDWARD COKE:

“… All infidels are in law perpetual enemies (for

the law presumes not that they will be

converted, that being a remote possibility) for

between them, as with the devils, whose

subjects they be, and the Christian, there is

perpetual hostility, and can be no peace …a

Pagan cannot have or maintain any action at all

[in the King's courts].

Lord Edward Coke

…If a Christian King should conquer a kingdom

of an infidel, and bring them under his

subjection, there ipso facto the laws of the

infidel are abrogated, for that they be not only

against Christianity, but against the law of God

and of nature, contained in the decalogue; and

in that case, until certain laws be established

amongst them, the King by himself, and such

Judges as he shall appoint, shall judge them

and their causes according to natural equity ….”

The Peace of Westphalia, 1648

Established modern European state system and following principles:

• Sovereignty of nation-states and the fundamental right of

political self-determination

• Legal equality between nation-states

• Internationally binding treaties between states

• Non-intervention of one state in the internal affairs of another state

• Cuius regio, eius religion (“Whose rule, his religion”)

The Origins of the “Denial” Policy

In British Columbia

“I think they are the ugliest and laziest

creatures I ever saw, and we should, as

soon think of being afraid of our dogs as

of them.”

Letter from Joseph Trutch to his wife Charlotte Trutch,

expressing his views on the Indians of the Oregon

Territory , 23 June 1850 (Trutch Papers)

“The Indians really have no right to the

lands they claim, nor are they of any

actual value or utility to them; I cannot

see why they should either retain these

lands to the prejudice of the general

interests of the Colony, or be allowed to

make a market of them either to

Government or to individuals.”

Joseph Trutch, Commissioner of Land Works for the

colonial government in British Columbia, 1867

Joseph Trutch, c. June 1870

The 1884 E &N Railway Grant and the Establishment of Reserves

Johnson v. McIntosh (1823)

CHIEF JUSTICE MARSHALL:

“…The exclusion of all other Europeans, necessarily gave

to the nation making the discovery the sole right of

acquiring the soil from the natives, and establishing

settlements upon it. It was a right with which no Europeans

could interfere. It was a right which all asserted for

themselves, and to the assertion of which, by others, all

assented.

Those relations which were to exist between the

discoverer and the natives, were to be regulated by

themselves. The rights thus acquired being exclusive, no

other power could interpose between them.”

The United Nations Decolonization Process

and the “Salt Water Thesis”

United Nations Human Rights System

The United Nations International Covenant

on Civil and Political Rights

Article 1:

“All peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right

they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their

economic, social, and cultural development.”

Article 27:

“In those States in which ethnic,

religious or linguistic minorities exist,

persons belonging to those

minorities shall not be denied the

right, in community with other

members of their group, to enjoy their

own culture, to profess and practice

their own religion, or to use their own

language.”

Canada’s Defense in Mikmaq Tribal Society v. Canada

UN Human Rights Committee (1980)

“International, American and Canadian law

do not recognize treaties with North

American Native People as international

documents confirming the existence of these

tribal societies as independent and

sovereign states. These treaties are merely

considered to be nothing more than

contracts between a sovereign and a group

of its subjects”

The Modern Indigenous Human Rights Movement

International Labour Organization

(No. 169) on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples

The UN Working Group on Indigenous

Populations

The Proposed American Declaration on

the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (OAS)

Inclusion of provisions concerning

indigenous children in the UN Convention

on the Rights of the Child

Inclusion of provisions concerning

indigenous peoples in major international

environmental instruments

UN Human Rights Committee

General Comment No. 23, interpreting article 27

(1994)

“With regard to the exercise of

the cultural rights protected under

article 27, the Committee observes

that culture manifests itself in many

forms, including a particular way of

life associated with the use of land

resources, especially in the case of

indigenous peoples. That right may

include such traditional activities

as fishing or hunting and the right

to live in reserves protected by law.”

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

(as adopted by the UN General Assembly, September 13, 2007)

Article 26

“Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories

and resources which they have traditionally owned,

occupied or otherwise used or acquired.

Indigenous peoples have the right to own, use, develop

and control the lands, territories and resources that they

possess by reason of traditional ownership or other

traditional occupation or use, as well as those which they

have otherwise acquired.

States shall give legal recognition and protection to these

lands, territories and resources. Such recognition shall

be conducted with due respect to the customs, traditions

and land tenure systems of the indigenous peoples

concerned.”

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Article 28

“Indigenous peoples have the right to redress,

by means that can include restitution or, when

this is not possible, of a just, fair and equitable

compensation, for the lands, territories and

resources which they have traditionally owned

or otherwise occupied or used, and which have

been confiscated, taken, occupied, used or

damaged without their free, prior and informed

consent.”

The Right to Consultation under the

UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Article 3

“Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination.

By virtue of that right they freely determine their political

status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural

development.”

Article 19

“States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the

indigenous peoples concerned through their own

representative institutions in order to obtain their free, prior

and informed consent before adopting and implementing

legislative or administrative measures that may affect

them.”

Report of the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation

of the human rights and fundamental freedoms of

indigenous peoples, S. James Anaya (2008)

“The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of

Indigenous Peoples represents an authoritative

common understanding, at the global level, of the

minimum content of the rights of indigenous peoples,

upon a foundation of various sources of international

human rights law. The product of a protracted drafting

process involving the demands voiced by indigenous

peoples themselves, the Declaration reflects and

builds upon human rights norms of general

applicability, as interpreted and applied by United

Nations and regional treaty bodies, as well as on the

standards advanced by ILO Convention No. 169 and

other relevant instruments and processes.”

Canada’s Position on the UN Declaration

"...Canada's position has remained consistent and

principled. We have stated publicly that we have

significant concerns with respect to the wording of the

current text, including the provisions on lands,

territories and resources; free, prior and informed

consent when used as a veto; self-government without

recognition of the importance of negotiations;

intellectual property; military issues; and the need to

achieve an appropriate balance between the rights and

obligations of indigenous peoples, member States and

third parties.”

Statement by Ambassador McNee to the General Assembly on the

Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 13 September 2007.

Inter-American Human Rights System (OAS)

Charter of the Organization of American States

Proclaims commitment of Member States to protect human rights.

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

- OAS Charter Organization; Comprised of 7 independent experts

- Issues State and thematic reports; adjudicate human rights complaints.

American Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man

Affirms many of the same rights as those in Universal Declaration of

Human Rights:

Article 2: “All persons are equal before the law and have

the rights and duties established in the Declaration, without

distinction as to race, creed, sex, language, creed or

any other factor.”

Article 23: “Every person has a right to own such private

property as meets the essential needs of decent living and

helps to maintain the dignity of the individual and of the

home.”

The Case of Awas Tingni vs. Nicaragua

Inter-American Court of Human Rights

Judgment of August 31, 2001

The Case of Awas Tingni vs. Nicaragua

Decision of the Inter-American Court (2001)

• Nicaragua violated the right to property by granting concessions

to exploit the resources on Awas Tingni traditional lands and by

not titling and demarcating those lands in favor of the community.

The right to property includes the collective right of indigenous

peoples to the enjoyment of their traditional lands and natural

resources.

• “…For indigenous communities, relations to the land are not

merely a matter of possession and production but a material and

spiritual element which they must fully enjoy, even to preserve

their cultural legacy and transmit it to future generations.”

• Nicaragua must cease acts which could cause agents of the State,

or third parties, to affect the existence, value, use or enjoyment of

the property of the Awas Tingni community and adopt measures of

legislative, administrative, and whatever other character for the

effective delimitation, demarcation, and titling of indigenous lands.

The Case of Dann vs. the United States

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

Report of October 2001 (Released July 2002)

“Where property and user rights of indigenous peoples arise from

rights existing prior to the creation of a state, [indigenous

peoples have the right to] recognition by that state of the

permanent and inalienable title of indigenous peoples relative

thereto and to have such title changed only by mutual consent

between the state and respective indigenous peoples when they

have full knowledge and appreciation of the nature or attributes

of such property. This also implies the right to fair compensation

in the event that such property and user rights are irrevocably

lost.”

Case of the Saramaka People v. Suriname

Inter-Am. Ct. H.R., Judgment of November 28, 2007

• “First, the State must ensure the effective participation of the

members of the Saramaka people, in conformity with their

customs and traditions, regarding any development, investment,

exploration or extraction plan … within Saramaka territory. By

‘development or investment plan’ the Court means any

proposed activity that may affect the integrity of the lands and

natural resources within the territory of the Saramaka people,

particularly any proposal to grant logging or mining concessions.

• Second, the State must guarantee that the Saramakas will

receive a reasonable benefit from any such plan within their

territory.

• Thirdly, the State must ensure that no concession will be

issued within Saramaka territory unless and until independent

and technically capable entities, with the State’s supervision,

perform a prior environmental and social impact assessment.”

Case of the Saramaka People v. Suriname

Inter-Am. Ct. H.R., Judgment of November 28, 2007

“…These safeguards are intended to

preserve, protect and guarantee the special

relationship that the members of the

Saramaka community have with their

territory, which in turn ensures their

survival as a tribal people.”

Canada’s Comprehensive Claims Process,

the British Columbia Treaty Commission, and

Indigenous Peoples Human Rights

UN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE

Comments on Canada (1999)

The Human Rights Committee

recommended that Canada reform its laws

and internal policies to guarantee the full

enjoyment of rights over land and

resources for the indigenous people of

Canada. Additionally, the Committee

recommended that Canada abandon “the

practice of extinguishing inherent

aboriginal rights … as incompatible with

article 1 of the Covenant. “

British Columbia’s First Nations

Canada’s Negotiating Mandates in the BCTC Process

• “Private lands” are not “on the table”

• Just compensation is not on the table/ BCTC process is

a “political process”/

• “Interest-based as opposed to rights-based approach”

• “Modified Rights/ Non-Assertion Model”

• Indemnity requirement and full and final settlement/

extinguishment for a treaty

• “Litigate or negotiate” policy

• The loan policy - “397M - and growing” (Vancouver Sun October 6, 2010)

• Municipal model of governmental powers/ refusal to

recognize inherent aboriginal right of self-government

UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

Concluding Observations: Canada (May 22, 2006), at para. 16.

“The Committee, while noting that the State party

has withdrawn, since 1998, the requirement for an

express reference to extinguishment of Aboriginal

rights and titles either in a comprehensive claim

agreement or in the settlement legislation ratifying

the agreement, remains concerned that the new

approaches, namely the “modified rights model” and

the “non-assertion model,” do not differ much from

the extinguishment and surrender approach.”

PETITION

to the

INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN

RIGHTS

submitted by

THE HUL’QUMI’NUM TREATY GROUP

against

CANADA

Submitted May 10, 2007

112. By unilaterally granting rights and interests in the traditional

lands and resources of the Hul’qumi’num peoples to private third

parties without ever consulting them, seeking their consent, or

offering restitution or payment of just compensation in return for a

valid extinguishment of their aboriginal title and property rights and

by permitting damaging logging and other development activities on

these lands used, occupied and relied upon by the Hul’qumi’num for

their cultural survival, Canada is acting in violation of the right to

property, the right to restitution for its taking, the right to cultural

integrity, the right to consultation and other human rights belonging

to the Hul’qumi’num as indigenous peoples.

18.

The CVRD Development Services Department Report for 2007

shows rapid growth in the key development permitting areas of zoning

amendments, subdivision activity, and development permit applications

over the past decade (1998-2007)…The statistics on the “Potential

Number of Parcels Created” by subdivision applications are particularly

alarming, showing a ten-year trend toward ever larger and larger

subdivisions, capped by 2007’s near threefold increase over the prior

year (from 270 to 752 potential parcels!):

1998- 52

1999- 92

2000- 97

2001- 115

2002- 185

2003- 303

2004- 401

2005- 316

2006- 270

2007- 752

Canada’s Submission in Response to the Commission

(May 11, 2008)

• Canada argues that “the HTG’s petition is

inadmissible because the HTG has not exhausted

readily available domestic remedies.”

– “HTG can address its claims through negotiations under the

BCTC Process.”

– “If the HTG believes that these negotiations are not

adequate to address the HTG concerns, the HTG could use

readily available domestic legal remedies to address its

claims.”

Canada’s Response:

95. The HTG asserts that Canada's courts "have

never legally recognized or affirmed one single

square inch of aboriginal title rights belonging to

indigenous peoples in their traditional lands that

were granted by the State in fee simple to private

third parties in British Columbia.”

96. The fact that a Canadian court has not made

such a specific declaration to date does not

demonstrate that a Canadian court never would, in a

properly plead case…

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

REPORT No. 105/09

Petition 592-07, Admissibility

Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group v. Canada

October 30, 2009

37.

…[T]he BCTC process has not allowed negotiations on

the subject of restitution or compensation for HTG ancestral

lands in private hands, which make up 85% of their

traditional territory. Since 15 years have passed and the

central claims of HTG have yet to be resolved, the IACHR

notes that the third exception to the requirement of

exhaustion of domestic remedies applies due to the

unwarranted delay on the part of the State to find a solution

to the claim.

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

REPORT No. 105/09

Petition 592-07, Admissibility

Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group v. Canada

October 30, 2009

37. …Likewise, the IACHR notes that by failing to resolve

the HTG claims with regard to ancestral lands, the BCTC

process has demonstrated that it is not an effective

mechanism to protect the right alleged by the alleged

victims. Therefore, the first exception to the requirement of

exhaustion of domestic remedies applies because there is

no due process of law to protect the property rights of the

HTG to its ancestral lands.

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

REPORT No. 105/09

Petition 592-07, Admissibility

Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group v. Canada

October 30, 2009

39.

The IACHR also considers relevant the experiences of

other Canadian indigenous groups described in the amicus

curiae briefs filed with the IACHR, which show the difficulties

they have faced when trying to access the legal remedies the

State contends must be exhausted by the HTG in order to

obtain recognition and protection of its ancestral lands. The

Commission notes that the jurisprudence cited by the State

recognizes the existence of the aboriginal title, the communal

nature of indigenous property rights, and the right to

consultation in the Canadian legal system. But, the amicus

briefs show that none of these judgments has resulted in a

specific order by a Canadian court mandating the demarcation,

recording of title deed, restitution or compensation of

indigenous peoples with regard to ancestral lands in private

hands…

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

REPORT No. 105/09

Petition 592-07, Admissibility

Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group v. Canada

October 30, 2009

41.

…The Commission notes that the legal

proceedings mentioned above do not seem to provide any

reasonable expectations of success, because Canadian

jurisprudence has not obligated the State to set

boundaries, demarcate, and record title deeds to lands of

indigenous peoples, and therefore in the case of HTG,

these remedies would not be effective under recognized

general principles of international law.