a literature review?

advertisement

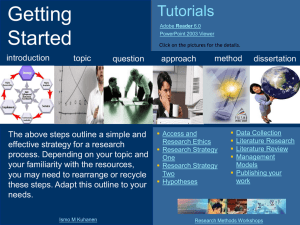

DISSERTATION 101: So, You’ve Completed Your Coursework, Aced Your Exams, and Gained Topic Approval. What’s Next? A n n e S w i t z e r, A s s i s t a n t P r o f e s s o r Outreach & Social Sciences Librarian switzer2@oakland.edu S h erry Wy nn Pe rdue, D irector Oakland University Writing Center wynn@oakland.edu Part I. Information Literacy • WHAT resources do you need? • WHERE can you find them? • HOW do you evaluate them? How Do You Get Started? Generate a research question. Locate sources that represent the breadth of responses to that research question. Research 101 • Consult your subject librarian liaison. • Utilize library research guides and subject specific databases. • Learn citation searching and how to find “seminal” works. • Examine past approved dissertations in your discipline. How Do You Evaluate Sources? • What are the credentials of the author(s)? Is s/he an authority? • Does it contain accurate, reliable information? • Is the source relevant to your dissertation topic? • Is the source free of biased information, opinion or positional advocacy? • Has the source been reviewed prior to publication through peer review? (Ulrich’s database) Part II: Composing the Literature Review • WHAT is (and is not) a literature review? • HOW should you frame the literature you locate? • How should you draft the literature review? • WHAT role does the committee play in your project? • WHERE is institutional support available? Getting Started • Do you understand the purpose and scope of a literature review? • Do you comprehend the difference between an abstract or an annotation and a literature review? • Have you examined dissertations that your chair values? Have you (and your chair) annotated these models to demonstrate why and how authors have succeeded? • If your dissertation is qualitative, look for qualitative models, etc. What is the Dissertation Literature Review? • A professional conversation framed by a guiding concept • A comprehensive exploration of existing scholarship on a specific topic • “An account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars. . .” (Taylor & Procter, 2001) • An answer to a persistent question (R. Elmore, Harvard Graduate School of Education) A well-framed (by theme, method, chronology, etc.) presentation of the current state of topic knowledge, which is designed to highlight past research findings and to pave the way for your study Characteristics of a Dissertation Literature Review • An introduction that shares the persistent question(s) the reviewed literature will address and indicates how the reviewed scholarship will be framed • An organizational frame, which groups relevant scholarship by topic, chronology, theoretical approach, methodology, etc. and/or a combination of approaches • A series of transitions organic to the discussion that indicate how different studies approach the same issues both within individual paragraphs and between paragraphs Characteristics of a Dissertation Literature Review • Evidence of how conflicting findings within the literature might be resolved by looking at the methodology, sample size, questions asked (and not asked), etc. • A conclusion that clarifies how the literature demonstrates the efficacy of the dissertation study. Does it demonstrate a gap in the literature? Does it identify a conflict that needs resolution? In many cases the specific research questions for the student author’s proposed study will be shared here too Literature Review Pitfalls: Forgetting to Frame Failing to synthesize ideas and information from your sources into a narrative account of what the professionals currently know with the purpose of credentialing your study • This synthesis could be framed by date, theoretical orientation, method, issue, etc. The literature review, however, is not an annotated bibliography. In other words, you organize the literature review by issues and ideas rather than by individual sources. Your goal is to create a conversation between and among the scholars on each important issue reviewed. Literature Review Pitfalls: Overreliance on Quotations Excessive quoting undermines your authority, drowns out your voice, and creates disturbances in the narrative flow. You gain your reader’s trust by sparingly and strategically using other people’s words. • In most cases, you should paraphrase the material, selecting only the portions of the original quote that you need. • Generally when you use consecutive words from the original, you must place quotation marks around all directly quoted material and use a parenthetical citation that includes the page number. This advice does not include the names of theories or tests, which are often quite long and should be included as used in the literature. Literature Review Pitfalls: Patching not Paraphrasing “Patching” occurs when you insert a series of borrowed ideas and phrases; these strings often differ only slightly if at all from the original wording, whereas paraphrasing involves both rewording and reorganizing the original material; “synonym swapping” is not a paraphrase. Patching is a form of plagiarism, even if the writer provides a parenthetical citation. • You can mediate the potential for plagiarism by taking accurate notes in your own words, carefully noting the source and page number. • You can ensure that the relationships between ideas and sources are clear by using rhetorically accurate transitions. For examples, see Graff and Birkenstein’s They say/I say: The moves that matter in academic writing (2010). To avoid patching, practice making this material your own. You will need to read a great deal more material than you cite. Literature Review Pitfalls: Cursory Overview or Biased Sample Haphazardly collecting research on your topic. • You must implement a specific search strategy and a culling strategy, which you can justify to your readers. Failing to ensure that your literature review is comprehensive because you were unaware of the seminal studies on the topic. • ISI Web of Science is helpful for locating such works. Consciously choosing to omit scholarship that challenges your initial hypothesis, methodology, etc. • If you narrow your review to two of three pedagogical approaches or to three potential antagonists among many, you must indicate the rationale for this decision. Whether intentional or not, these omissions will invalidate your claims. Further, you may find it necessary to consider this pitfall as you evaluate other scholars’ research. Literature Review Pitfalls: Failing to Connect Foundational Studies to Your Project Citing “seminal” works—studies that are most cited by others— without demonstrating how these significant, early studies complement, qualify, or contrast with the approach taken in your research. • While it is helpful to consult reviews of the literature most crucial to your subject (because they can guide your understanding of your own source base), it is essential to gain a firm understanding of the foundational studies that will contribute to the argument you make. Everything you discuss in your literature review needs to pave the way for your project. Getting Started: The Source Grid • A graphic organizer that helps you document your “talking points,” the level one headers of your literature review • A non-linear outline of the major topics that your literature review will synthesize Drafting from the Source Grid Read, evaluate, and group the literature by major topics or talking points, which become the columns of the source grid. Draft one column at a time. In other words, compose the text like a quilt. Each paragraph/section develops an idea rather than simply summarizes the results of one article. While there are times that an individual study might occupy a whole paragraph (it could be the only study on an important issue), usually the paragraphs situate studies on similar topics in relationship to one another using transitions that indicate the relationship between and among the sources (similar/different method, similar/different result, similar/different explanation of a problem, etc.) Caution: Never compose a draft without including an citation for each source as you go. For a sad example of what can happen when this advice is neglected, listen to this story about Pulitzer Prize winning historian Steven Ambrose. Example One Unwilling to equate research and legitimacy with quantitative methods, some compositionists employed qualitative methods in the late 1970s and early 1980s: Donald Graves (1979) used case studies, Linda Flower and John Hayes (1981) turned to speak-aloud protocols, Shirley Brice Heath (1983) explored community literacy via ethnography, and Nancie Atwell (1987) advocated reflective practice. Increased qualitative scholarship was not the only factor contributing to the methodological debate, however. These new practices reflected the emergence of identity politics and the growing influence of poststructuralism in academe (Smagorinsky, 12). The works of Derrida, Foucault, DeMan, and Bakhtin, founded on semiotics and poststructuralist theory, encouraged English literature and composition scholars to resist what they claimed as the objectivism in data-driven research. While critics rightfully argued that the method should fit the question and the audience, many advanced an implicit (later explicit) assumption that social science methods were not adequate to the task. Example Two In addition to the above studies on dissertator difficulties, the Carnegie Foundation’s Carnegie Initiative on the Doctorate (CID) has yielded essay collections like Envisioning the future of doctoral education (Golde & Walker, 2006) and The formation of scholars (Walker et al., 2008). Both acknowledge how dissertators struggle. These volumes echo criticisms from previous decades, particularly those made by Koefod (1964), of how graduate education shortchanges dissertation writers. Although these volumes make salient critiques and offer nuanced suggestions about reform, the 2006 volume’s discussion of the “dissertation problem” was primarily limited to 1) the loneliness Madsen (1992) addressed and 2) the increasing pressure to publish while in graduate school (Golde & Walker, 2006, p. 352). The 2008 volume, however, leveraged critiques of “poorly written, poorly conceptualized, and poorly executed dissertations,” sometimes attributed to doctoral supervision by researchers like Lovitts (2007), and it examined laments that too often dissertations “lie mouldering in their library graves” (Tronsgard, 1963, p. 493, as cited in Walker et al., 2008). In response, its authors addressed ways to combat attrition at the dissertation stage, such as integrative dissertations—dissertations that are not subject to the less structured problems that Katz (1997) addressed. They cite dissertations composed in the University of Michigan’s Chemistry program, which consist of research projects done in conjunction with their faculty members. In sum, this volume addresses more timely critiques and begins in a tangible way to discuss the potential of the collaborative dissertation that some see as the future of the dissertation for certain disciplines. Drafting and Integrating the Parts • • • • • To mediate distractions, Sherry finds it helpful to open a separate document for each talking point into which I paste its grid material. If a good idea for a different part of the paper intrudes on my process, I quickly click on that document and record the idea before returning to the issue on which I am currently writing. Continue to draft new talking points and redraft previously composed talking points until you have good fragments (quilting squares) of the paper’s body. Once you have the parts, you need to examine them in relationship to one another to determine which talking points must come first. After you determine the order of information within the body of the review, it is time to insert and refine your transitions. After composing the body, draft the introduction and the conclusion. Caution: It is never a good idea to draft these before you know how the literature will come together. Committee Concerns: Your Chair • With whom do you work best? Under what circumstances have you • • • • • • worked with this person in the past? Is s/he good at meeting deadlines and responding to questions and submitted work? Will s/he read each chapter in a timely manner and offer feedback on higher order concerns? Does this faculty member understand and appreciate your research question and your methodology? Will s/he work well with the rest of the committee? Will s/he agree to let you seek guidance from members of the committee before your proposal defense? Is s/he in a position to be both your coach and your buffer, as needed? Will s/he provide you a model from which to follow? Committee Concerns: Members • Do potential members know you, your work, and your chair? • Will each potential committee member’s expertise complement your project? • Can those you select work well with and defer to your chair? • Will they meet with you to offer guidance before you draft the proposal? Time Management • Develop a timetable that breaks down the dissertation into a series of manageable weekly tasks. • Start the process early! • Leave plenty of time for rewrites and edits. • Request feedback as you go, rather than waiting until a chapter is done. When Should You Schedule a Writing Consultation? • After the research consultation (but before you start writing) to make a • • • • • • plan and review the project specifications After you have located and started reading your sources to discuss potential talking points/headers for a source grid After you have created a source grid to explore potential ways to situate the issues within each major topic Once you have drafted a section of the paper Whenever you need help with documentation Once you have a solid working draft, etc. Anytime you get stuck or need a second set of eyes Selected References Elmore, R. Some guidance on doing a literature review. Retrieved on January 15, 2010 from http://www.gse.harvard.edu/library/services/research_instruction/el more_lit_review.pdf Graff, G. & Birkenstein, C. (2006).They say/I say: The moves that matter in academic writing. New York: W.W. Norton. Taylor, D. & Procter, M. (2001). The literature review: A few tips on conducting it. Retrieved January 4, 2010 from: http://www.utoronto.ca/writing/litrev.html University of Washington Psychology Writing Center. (2004). Writing a psychology literature review. Retrieved January 15, 2010 from http://depts.washington.edu/psywc/handouts/pdf/litrev.pdf Thank You! Anne and Sherry appreciate the opportunity to speak with you about this high stakes manuscript. Please feel free to schedule a Research Consultation or a Writing Consultation for assistance at any stage of the research and writing process as you move forward.