THE INFLUENCE OF WORKING MEMORY, SPATIAL REPRESENTATION AND PERSONALITY FACTORS

IN NAVIGATING A VIRTUAL ENVIRONMENT.

Simona Gardini, Francesca Pazzaglia, Massimiliano Martinelli, Diego Varotto

Department of General Psychology, University of Padua, Italy, simona.gardini@unipd.it

INTRODUCTION

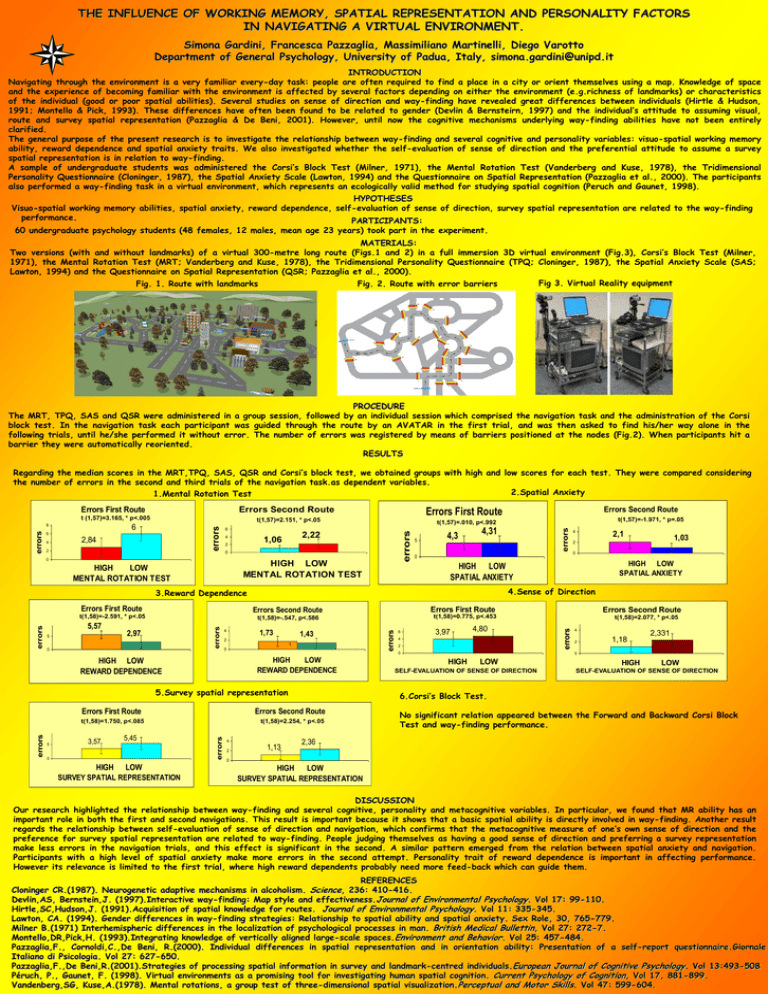

Navigating through the environment is a very familiar every-day task: people are often required to find a place in a city or orient themselves using a map. Knowledge of space

and the experience of becoming familiar with the environment is affected by several factors depending on either the environment (e.g.richness of landmarks) or characteristics

of the individual (good or poor spatial abilities). Several studies on sense of direction and way-finding have revealed great differences between individuals (Hirtle & Hudson,

1991; Montello & Pick, 1993). These differences have often been found to be related to gender (Devlin & Bernsteirn, 1997) and the individual’s attitude to assuming visual,

route and survey spatial representation (Pazzaglia & De Beni, 2001). However, until now the cognitive mechanisms underlying way-finding abilities have not been entirely

clarified.

The general purpose of the present research is to investigate the relationship between way-finding and several cognitive and personality variables: visuo-spatial working memory

ability, reward dependence and spatial anxiety traits. We also investigated whether the self-evaluation of sense of direction and the preferential attitude to assume a survey

spatial representation is in relation to way-finding.

A sample of undergraduate students was administered the Corsi’s Block Test (Milner, 1971), the Mental Rotation Test (Vanderberg and Kuse, 1978), the Tridimensional

Personality Questionnaire (Cloninger, 1987), the Spatial Anxiety Scale (Lawton, 1994) and the Questionnaire on Spatial Representation (Pazzaglia et al., 2000). The participants

also performed a way-finding task in a virtual environment, which represents an ecologically valid method for studying spatial cognition (Peruch and Gaunet, 1998).

HYPOTHESES

Visuo-spatial working memory abilities, spatial anxiety, reward dependence, self-evaluation of sense of direction, survey spatial representation are related to the way-finding

performance.

PARTICIPANTS:

60 undergraduate psychology students (48 females, 12 males, mean age 23 years) took part in the experiment.

MATERIALS:

Two versions (with and without landmarks) of a virtual 300-metre long route (Figs.1 and 2) in a full immersion 3D virtual environment (Fig.3), Corsi’s Block Test (Milner,

1971), the Mental Rotation Test (MRT; Vanderberg and Kuse, 1978), the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire (TPQ; Cloninger, 1987), the Spatial Anxiety Scale (SAS;

Lawton, 1994) and the Questionnaire on Spatial Representation (QSR; Pazzaglia et al., 2000).

Fig 3. Virtual Reality equipment

Fig. 1. Route with landmarks

Fig. 2. Route with error barriers

PROCEDURE

The MRT, TPQ, SAS and QSR were administered in a group session, followed by an individual session which comprised the navigation task and the administration of the Corsi

block test. In the navigation task each participant was guided through the route by an AVATAR in the first trial, and was then asked to find his/her way alone in the

following trials, until he/she performed it without error. The number of errors was registered by means of barriers positioned at the nodes (Fig.2). When participants hit a

barrier they were automatically reoriented.

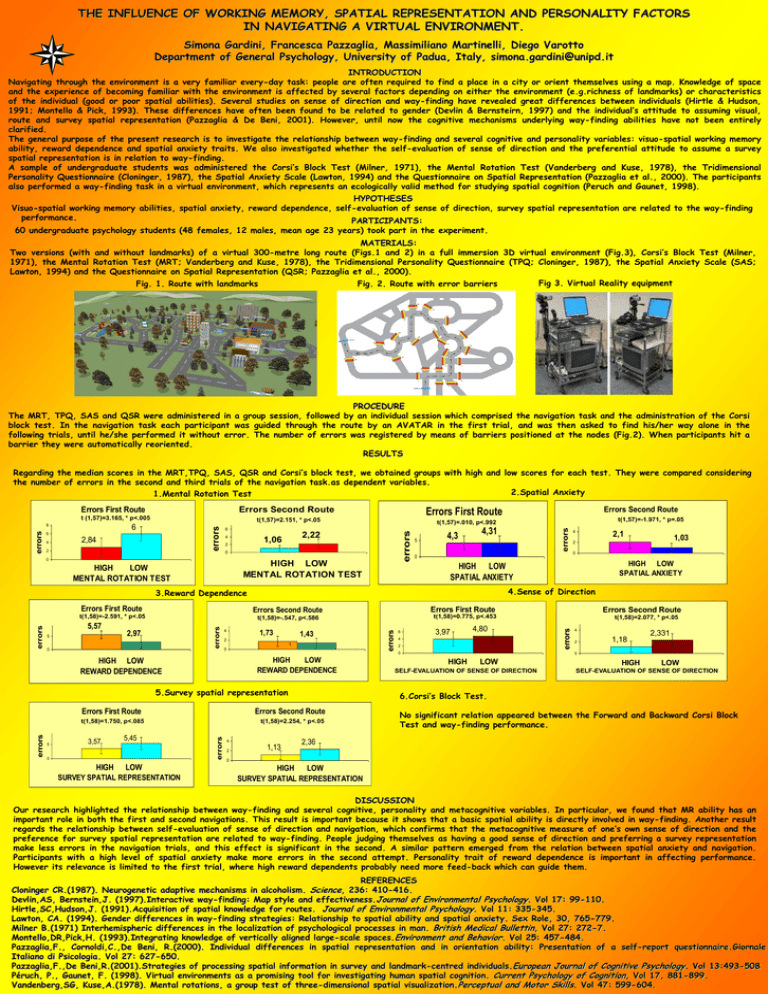

RESULTS

Regarding the median scores in the MRT,TPQ, SAS, QSR and Corsi’s block test, we obtained groups with high and low scores for each test. They were compared considering

the number of errors in the second and third trials of the navigation task.as dependent variables.

2.Spatial Anxiety

1.Mental Rotation Test

Errors Second Route

6

4

2,84

2

6

4

2,22

1,06

2

0

0

HIGH LOW

MENTAL ROTATION TEST

HIGH

LOW

MENTAL ROTATION TEST

5

4,3

4,31

0

2,97

0

1,73

1,43

2

1

0

HIGH

LOW

REWARD DEPENDENCE

5.Survey spatial representation

Errors First Route

0

HIGH LOW

SURVEY SPATIAL REPRESENTATION

t(1,58)=2.254, * p<.05

errors

errors

5

3,57

4

2

HIGH LOW

SPATIAL ANXIETY

1,13

Errors Second Route

3,97

4,80

4

2

t(1,58)=2.077, * p<.05

4

2

1,18

2,331

,18

0

HIGH

LOW

SELF-EVALUATION OF SENSE OF DIRECTION

HIGH

LOW

SELF-EVALUATION OF SENSE OF DIRECTION

6.Corsi’s Block Test.

Errors Second Route

t(1,58)=1.750, p<.085

5,45

6

0

HIGH LOW

REWARD DEPENDENCE

0

t(1,58)=0.775, p<.453

errors

5

4

1,03

2

Errors First Route

t(1,58)=-.547, p<.586

errors

errors

5,57

2,1

4.Sense of Direction

Errors Second Route

t(1,58)=-2.591, * p<.05

4

HIGH LOW

SPATIAL ANXIETY

3.Reward Dependence

Errors First Route

t(1,57)=-1.971, * p=.05

t(1,57)=.010, p<.992

errors

6

errors

errors

8

t(1,57)=2.151, * p<.05

errors

t (1,57)=3.165, * p<.005

Errors Second Route

Errors First Route

errors

Errors First Route

No significant relation appeared between the Forward and Backward Corsi Block

Test and way-finding performance.

2,36

0

HIGH LOW

SURVEY SPATIAL REPRESENTATION

DISCUSSION

Our research highlighted the relationship between way-finding and several cognitive, personality and metacognitive variables. In particular, we found that MR ability has an

important role in both the first and second navigations. This result is important because it shows that a basic spatial ability is directly involved in way-finding. Another result

regards the relationship between self-evaluation of sense of direction and navigation, which confirms that the metacognitive measure of one’s own sense of direction and the

preference for survey spatial representation are related to way-finding. People judging themselves as having a good sense of direction and preferring a survey representation

make less errors in the navigation trials, and this effect is significant in the second. A similar pattern emerged from the relation between spatial anxiety and navigation.

Participants with a high level of spatial anxiety make more errors in the second attempt. Personality trait of reward dependence is important in affecting performance.

However its relevance is limited to the first trial, where high reward dependents probably need more feed-back which can guide them.

REFERENCES

Cloninger CR.(1987). Neurogenetic adaptive mechanisms in alcoholism. Science, 236: 410-416.

Devlin,AS, Bernstein,J. (1997).Interactive way-finding: Map style and effectiveness.Journal of Environmental Psychology. Vol 17: 99-110.

Hirtle,SC,Hudson,J. (1991).Acquisition of spatial knowledge for routes. Journal of Environmental Psychology. Vol 11: 335-345.

Lawton, CA. (1994). Gender differences in way-finding strategies: Relationship to spatial ability and spatial anxiety. Sex Role, 30, 765-779.

Milner B.(1971) Interhemispheric differences in the localization of psychological processes in man. British Medical Bullettin, Vol 27: 272-7.

Montello,DR,Pick,H. (1993).Integrating knowledge of vertically aligned large-scale spaces.Environment and Behavior. Vol 25: 457-484.

Pazzaglia,F., Cornoldi,C.,De Beni, R.(2000). Individual differences in spatial representation and in orientation ability: Presentation of a self-report questionnaire.Giornale

Italiano di Psicologia. Vol 27: 627-650.

Pazzaglia,F.,De Beni,R.(2001).Strategies of processing spatial information in survey and landmark-centred individuals.European Journal of Cognitive Psychology. Vol 13:493-508

Péruch, P., Gaunet, F. (1998). Virtual environments as a promising tool for investigating human spatial cognition. Current Psychology of Cognition, Vol 17, 881-899.

Vandenberg,SG, Kuse,A.(1978). Mental rotations, a group test of three-dimensional spatial visualization.Perceptual and Motor Skills. Vol 47: 599-604.