Angus Macfarlane presentation Tuia Te Ako 2013

advertisement

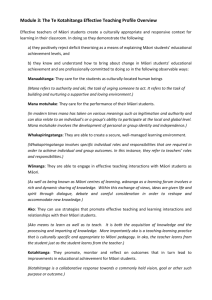

Diversity and the Academy Reasons for Hope Angus H Macfarlane University of Canterbury Aims of this Presentation • Reflect on some key drivers within the whakapapa theme • Introduce an additional question – one that refers to ‘a cultural reality’ • Consider a set of four ‘knowledge areas’ • Revisit briefly Kaupapa Māori imperatives • Outline five influential factors that offer reasons for hope in the academy • UC - Tō mātou whakapapa Two questions are relevant to Tuia te Ako 2013 (Durie, 2013) 1. How can Māori successfully participate in tertiary education? 2. How can the tertiary education sector add value to te ao Maori? Consider a third question: Does the academy have a clear and honest understanding of the reality in terms of Māori imperatives and perspectives? Ways of responding to that third question • • • • • • Truths tolerated Data sought Experiences tasted Assumptions challenged Talk generated Feelings respected Some knowledge areas • Technical knowledge – analytical or quantitative knowledge which can provide empirical support for observable changes in that which is being observed, or those who are being considered in the research constructs (see Mercier, 2012) • Practical knowledge – interpretative or qualitative knowledge, how meaningful something is after the research process has run its course (see Matamua, 2013; see Savage, et al., 2013) • Reflective knowledge – developing interventions that will make a social decision – turning a value into practice (see Durie, Kingi & Graham, 2012) • Indigenous knowledge - Māori knowledge being perceived as having an integrity of its own (see Durie, 1997) A Methodological History • The dominance of quantitative methods as wave 1 • The emergence of qualitative methods as wave 2 • The growth of mixed methods as wave 3 And in New Zealand, a wave of Kaupapa Māori and Indigenous Methodologies (Smith, 1999; 2012) Why Kaupapa Māori research? To provide support for those who wish to: • Challenge, question and critique expressions of dominant hegemony (G Smith, 1997; 2007) • Engage with and seek to intervene in unequal power relations (ibid) • Transform Māori aspirations (Pihama, 2012) • See it as a movement and a consciousness (Cram, 2001) • Contend that to hold alternative histories is to hold alternative knowledges (L Smith, 1999; 2012) • Offer a way of working for professional staff carrying out culturally related research, individually and in collaboration with others, in their place of work (Macfarlane, 2010; Russell, 2012) What constitutes evidence and who decides? Hammersley (2001) believes that: “The process of defining what constitutes ‘evidence’ will be fraught with difficulty, should the privileging of research evidence over evidences from other sources result.” Professional and whānau wisdom and values therefore, should not be trumped, overlooked or marginalised An ‘Animal Farm’ analogy…. That espouses the notion that …. All evidence is equal… But some evidence is more equal than others An even playing field? 10 What are the main dangers of Eurocentric hegemony in the academy? 1. The lack of attention to alternatives to mainstream knowledge (which is not only Eurocentric but typically focused on middle-class beliefs and practices) has the potential to leave the academy bereft 2. There is the potential for damage because of the 'colonisation' of local knowledge, theory and practice by Eurocentric thought. The dominance of Eurocentric ways of researching and teaching helps legitimise world-wide inequality Adapted from Howitt, D & Owusu-Bempah, J. (1994). The Racism of Psychology. London: Routledge In consideration of theories (L Smith, 1999, p. 38) • Theory at its most simple level is important • It makes sense of reality • It helps us to make assumptions and predictions about the world in which we live • It incorporates methods for selecting, arranging, prioritising, and legitimising what we see and do • It enables us to deal with contradictions and uncertainties • It allows for new ideas to emerge, and to merge • It is timely to promote Māori theory (Winiata, 2008; 2010) Five influences of culturally responsive provision in C21 tertiary education • Content integration • Knowledge construction • Equity practices • Skilled providers • Empowering organisational cultures Empowering Organisation Content Integration Knowledge Construction Empowering Organisation Content Integration • Build on the existing knowledge • Integrate new, or additional, culturally-based content into the existing socio-scientific constructs • Draw from Dewey – Open up a fields of scholarship that refers to the individual having a stake in the learning activities or experiences • Draw from Penetito – Open up fields of scholarship that determine the importance of ‘place’ having a stake in the research activities and experiences • Draw from Durie - Open up fields of scholarship to Māori ways of understanding and thinking Knowledge Construction • Ask ourselves as tertiary education leaders to go deeper into our analyses of the curriculum, the pedagogical factors • Carefully consider how we decide what is useful knowledge and how we organise and frame that knowledge • Whose knowledge? • From what perspective is knowledge generated? • Is it foundational and relative to the worldviews that are held dearly? Equity Practices? • Are the principles of the Treaty understood and applied? • (Liu, 2010) coined the phrase “Strong on rhetoric, low on commitment”. If this phrase applies in our organisation in reference to the Treaty and resourcing, then what? • What external factors might cause gaps between equity policy and implementation? • Can/should we assume that most/all educators will want to work towards addressing equity issues? Skilled Providers • Have theoretical bases • Insist on research adeptness • Stress contextual relevance • Offer exemplars that provide additional understanding, and • Invite participation Empowering Organisation Culture … is one that is designed and operated with thoughtful attention to the myriad of ways that aspects of culture can be encoded into the basic structures of the organisation •Adopts a distinctive identity which is bicultural •Phases out the ‘them and us’ (rātou) model •Phases in a ‘tātou’ model •Withholds a ‘mātou’ model •Develops an accountability structure aligned to a set of culturally-oriented competencies In pursuit of a balance – me haere whakamua tonu A plan to ‘rise above the challenge…’ • Adopt a goal • Consider a response • Generate a process Adapt the thinking of Joyce and Showers (1989, 2004) • Reticent consumers • Passive consumers • Enthusiastic consumers Whakapapa: Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha Core Values UC Vision 2020 Ngāi Tahu RC UC Research Plan Māori Strategy Māori Research Advisory Gp TE TIRITI O WAITANGI Research & Innovation Office of the Assistant Vice-Chancellor Māori Internal resources External resources Māori Development Team Arts 22 Engineering Science Outcomes Business & Law Education Diversity and the Academy …. reasons for hope • Challenge the status-quo • Critique the knowledge we take for granted • Acknowledge epistemologies of local wisdom and global considerations • Look for different angles • Look for how our children, your children, their children, can grow up in the best possible way