PowerPoint for Alan Trachtenberg`s “Albums of War: Reading Civil

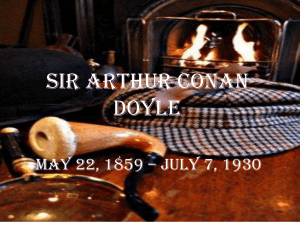

advertisement

Alan Trachtenberg’s “‘Albums of War’: On Reading Civil War Photographs” Tuesday, February 22nd, 2011 “The mere notation of photography, when we introduce it into our meditation on the genesis of historical knowledge and its true value, suggests this simple question: COULD SUCH AND SUCH A FACT, AS IT IS NARRATED, HAVE BEEN PHOTOGRAPHED?” How do photographs shape what we call “memories” and what we call “knowledge”? Valéry’s “innocent seeming” question Mathew B. Brady, with whose name the entire project of photographing the Civil War has long been identified, “was more an entrepreneur than a photographer, the proprietor of fashionable galleries in Washington and New York” (Trachtenberg 289). Brady and the manager of his Washington gallery, Alexander Gardener, quarreled over who should receive credit for the photographs signed “Brady” (as Brady himself was not the cameraman). “It can be said that whoever may have authored Brady’s images, ‘Brady’ authorized them, gave them imprimateur” (289). SEE FIG. 1. One particular red herring: Brady as photographer “The inventorial form was, of course, neither Brady’s invention nor unique to his practice; it was simply the most obvious, even ‘natural’ way to list such images. The very obviousness of the form is precisely what makes it at once so potent as a vehicle of cultural meaning and so hard for us to see…The catalog empowers the image, then, not as picture but as datum, an item of sequential regularity” (Trachtenberg 291). See FIG. 2. The inventorial form and cultural meaning Technological change leading up to the Civil War Exposure time reduced in wet-plate production process, enabling stop-action representations of moving scenes Negative-positive process enables reproduction of unlimited numbers of images from individual negatives Stereographs introduce three-dimensionality as a new condition of viewing images, “mak[ing] them seem virtual simulacra of the perceptible world” (Trachtenberg 292). Detail in such “frightful amount” Trachtenberg’s subjects: Gardener’s Photographic Sketchbook of the Civil War (Alexander Gardener, 1866) Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign (George P. Barnard, 1866) Photographs Illustrative of Operations in Construction and Transportation (manual written by Herman Haupt, with photographs by A.J. Russell, 1863) The dilemma: How can such albums manage to depict war as a felt event in everyday life when the medium through which they’re communicating values, more than anything else, “keeping a record”? (The larger dilemma still presents itself in the practice of “serious photography,” thought to be antipictorial, representing detail indiscriminately and drawing from an archival base.) The album and the construction of narrative Trachtenberg’s conclusion about Holmes’ “The Doings of the Sunbeam” (a companion piece to “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph”): “[I]n the essay as a whole Holmes virtually diagrams a process of self-blinding, of seeing and forgetting, repressing and displacing, that is a sign of ideology…[the photos] seeming to be without mediation being precisely the message of an ideology…” (298). In the “honest sunshine”: Oliver Wendell Holmes and the ideology of the photo Review the images from Gardener’s album (figures 4-8), his “tour” of the war. Then, consider Trachtenberg’s question: “Are these photographic constructions free, then, of the difficulties experienced by Holmes and apprehended by Whitman—difficulties arising from the antithetical character of the war itself, its fissure we can think of as sundering not only hearthstones but also livid details of war from overarching ideologies, from containing narratives?” How do texts (captions, essays, and full texts) place interpretive demands on images? “The real war will never get in the books” – Whitman, Specimen Days On Thursday, we’ll focus more closely on Whitman’s account of the Civil War in Specimen Days (1892) and his reflection on a more industrialized, post-war America in Democratic Vistas (1871). You should also look at the frontispieces Whitman used in various editions of Leaves of Grass and consider how the self-portraits he chose placed interpretive demands on his text (specifically, a poem like “Song of Myself”) as well as how the text places demands on the portraits: http://www.whitmanarchive.org/published/index. html For next time…