PP Gerry Devlin

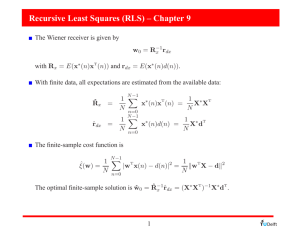

advertisement

Professional Competence and Reflective Practice Teachers as lead intellectuals! ‘the lad/lass o pairts’ Dimensions of Development Evidenced by • greater complexity in teaching e.g. in handling mixed-ability classes, reluctant learners, classes marked by significant diversity, or inter-disciplinary work; • the deployment of a wider range of teaching strategies; • the ability to adduce evidence of one’s effectiveness; • basing teaching on a wider range of evidence, reading and research; and A pronounced capacity for self-criticism and self-improvement; the ability to impact on colleagues through mentoring and coaching, modelling good practice, contributing to the literature on teaching and learning and public discussion of professional issues, leading staff development , all based on the capacity to theorise about policy and practice. A confluence of three ideas Problem Solving Research Lesson Study Communities of Practice Karl Popper Problem solving and the nature of knowledge P1 TS EE P2 Knowledge as problem solving • Retrograde Motion Sharpe, R. (2004) Professional Knowledge is no longer viewed as just consisting of a standardised, explicit and fixed knowledge base. It is now seen as knowledge which exists as knowledge in use, is ethical in its use and is changed by experience. The distinctive nature of professional knowledge lies in the interplay between its construction and use. When teachers use their knowledge, use changes what knowledge is. Research Lesson Study (RLS) TS1 P1 TS2 TSn EE P2 Professional Communities Community as normative prescription or empirical description Gemeinschaft or Gesellschaft? A Definition Communities of practice are groups of people informally bound together by shared expertise and passion for a joint enterprise. They are not new: e.g.1 corporations of metal workers, potters, and masons in Classical Greece e.g.2 Craft Guilds in the Middle Ages How they compare with other groups. A Snapshot Comparison Communities of practice, formal work groups, teams and informal networks are useful in complementary ways. Below is a summary of their characteristics. Community of practice Formal work group Project team Informal network What’s the purpose? Who belongs? What holds it together? How long does it last? To develop members’ capabilities; to build and exchange knowledge Members who select themselves Passion, commitment, and identification with the group’s expertise As long as there is interest in maintaining the group To deliver a product or service Everyone who reports to the group’s manager Job requirements and common goals Until the next reorganisation To accomplish a specified task Employees assigned by senior management The project’s milestones and goals Until the project has been completed To collect and pass on business information Friends and business acquaintances Mutual needs As long as people have a reason to connect negotiated enterprise mutual accountability interpretations rhythms local response joint enterprise mutual engagement engaged diversity doing things together relationships social complexity community maintenance shared repertoire stories styles artefacts actions tools historical events discourses concepts Dimensions of practice as the property of a community •Mutual engagement •A joint enterprise •A shared repertoire ‘Communities of practice’ Learning, Meaning and Identity Etienne Wenger 2006 They don’t replace existing structures but complement them and radically galvanise knowledge sharing, learning and change However, the organic, spontaneous and informal nature of communities of practice makes them resistant to supervision and interference! Successful managers cannot mandate communities of practice they can only hope to create them together by: • providing an infrastructure to nurture them; and • bringing the right people together. Competent membership of a community of practice • The ability to engage with other members and respond to their actions; • The ability to establish relationships as a basis for participation; • The ability to understand the work of the community deeply enough to take some responsibility for it; and • The ability to make use of the repertoire of practice to engage in the history of practice and to make this history newly meaningful. Communities of Practice: the Organisational Frontier? & Organisational Challenges Burns and Stalker -The Management of Innovation Ideal types (after Weber) Mechanistic organisations V Organic organisations A Practical example The Problem (P1) Pupils in key stage 3 don’t work well in groups TLRP findings (1) Blatchford et al (2001-2004) Group work can be made to work with benefits to attainment, motivation and behaviour. Group work skills need to be approached developmentally: social skills first, then communication skills, then problemsolving. TLRP findings (2) McGuinness and Sheehy (2001-2004) Developing pupils’ capacity to learn takes time and special attention needs to be paid to those with poorer cognitive and social resources. This in turn requires teachers to develop both their practices and their beliefs about learners. TLRP findings (3) Hughes et al and Brookes Attention needs to be given to the creation of positive classroom climates characterized by respect, trust and mutual exchange of dignity. The most fundamental form of education – the process of becoming a person – requires as much careful consideration as the acquisition of knowledge and skills. Personalized provision in schools should build on an understanding of the development of these strategic biographies, and respond to the social, cultural and material experiences of different groups of learners Tentative solution Plan a lesson which approaches group work from a development perspective. What social and communication skills do we need to explicitly factor into our lesson plan? How can we build a positive classroom climate which facilitates pupils working in groups? RLS (1) and (EE) RLS(2) and (EE) RLS (n) and (EE) Modified problem 1 or new problem 2 Process begins anew Professional competence leading to Ontological security