Huck Finn - Wayzata Public Schools

advertisement

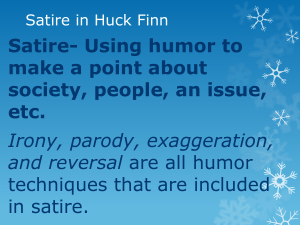

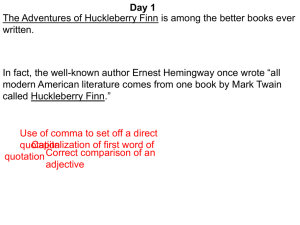

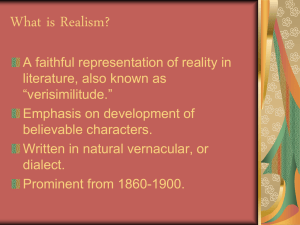

From 1865 to 1915, writers turned away from Romanticism and strove to portray life as it was actually lived. The major literary movements of the period were Naturalism, Regionalism, and Realism. Realism: attempted to present a “slice of life”: sought to portray ordinary life as real people live it and attempted to show characters and events in an objective, almost factual way. Science played a part, as well: The objectivity of science struck many writers as a worthy goal for literature. So a realist had to mind meaning in the commonplace. Naturalism: Showed life as the inexorable working out of natural forces beyond our power to control. Regionalism: blended Realism with Romanticism: emphasized place, and the elements that create local “color”: customs, dress, speech, and other local differences. During this time, the short story became a popular vehicle, using specific details to create a sense of realism and to capture local color. Characters were drawn from the mass of humanity and spoke in dialect, capturing the flavor and rhythms of common speech. “All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain.” Ernest Hemingway. Literary critic Joseph Claro interpreted Hemingway’s remark this way: “He didn’t mean that no Americans before Mark Twain had written anything worthy of being called literature. What he meant was that Twain was responsible for defining what would make American literature different from everybody else’s literature.” How? Twain was the first major writer to use real American speech to deal with themes and topics that were important to Americans. Huck has a strong regional dialect, which makes him even more likable and forces the reader to see things through Huck’s eyes. Like all great writers, Twain altered the consciousness of the people he wrote for; and he re-defined the terrain for all writers who came after him. Part of the answer as to why the novel is so real lies in the way it is told. Twain said a “good character” to tell his own story “in the first person” was in fact Huckleberry Finn, who was based on a Hannibal childhood contemporary named Tom Blankenship, from a family of poor whites and whose father was the town drunkard. Dialect is variation of a given language spoken in a particular place or by a particular group of people. A dialect is distinguished by its vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation. If we’re only talking about pronunciation, we usually use the term “accent.” Dilalect is applied most often to regional speech patterns, but a dialect may also be defined by other factors, such as social class. Huck’s voice, its tone and idiom, its “dialect” pronunciation, were among the things that seemed literally “real” to Mollie Clemens, Mark’s sister-in-law. Huck’s voice in the finished novel seems so natural that it almost appears to have been “found” or simply remembered and copied down. From the opening sentence to the last, Huck talks to us, and we share his thoughts and feelings, and seem to share his very experience. “Color” or local flavor in Huck Finn: Customs: Jim’s superstitions. Dress: How the duke and king are dressed in various parts of the story. Speech: Huck’s and Jimi’s dialects. Speaking of Jim’s dialect: It’s hard to decode at times: Take your time reading it. In the end, it’s not that different from Huck’s. Twain seems to be saying it is not our innate abilities, but rather our societal exposure and opportunities, that often dictate how we express ourselves. A picaresque novel: Involves clever rogues or adventurers. A genre of generally satiric prose fiction that depicts in realistic, often humorous detail, the adventures of a roguish hero of low social degree living by his or her wits in a corrupt society. Picaresque is a Spanish word; the most famous novel of this type is Don Quixote by Cervantes, a Spanish writer. These are similar to an action-adventure TV series in which a main character survives by his wits, usually engaging in violence and often breaking the law to get things done. This character is admirable because of bravery, quick thinking, or strength. Yet, they are not characters parents want their children to emulate: which is one of the criticisms of Huck Finn. Twain “broke the mold” by making Huck the narrator; telling the story in Huck’s language and point of view; and perhaps most picaresque, making Huck likeable as our hero. Huck possesses many of the qualities of a picaresque hero. He is an outcast from society. He sees himself as a sinner by society’s code for helping Jim escape. He shows the reader the false values of Southern United States society while keeping the readers’ sympathy on his side. Twain does this by “talking over” Huck’s head to the reader: We understand things that Huck does not, which lets us know how Twain wants us to feel. Right from the start, Twain has Huck introduce himself in a casual manner and comment on the author as someone who used “stretchers.” Twain expects us to see Tom Sawyer’s adventures and gang as young boy silliness, even though Huck doesn’t. Other examples: Pap’s complaints about not getting any justice from the government when he has had “all the anxiety and expense” raising a child. Pap berates a government that allows a black professor to vote right along with a white man like Pap. “Everybody was sorry [Emmeline Grangerford] died…but I reckon, that with her disposition, she was having a better time in the graveyard.” Huck is naïve and means this statement literally: Emmeline doted on death and therefore would presumbably be happiest among the dead. Twain, in contrast, is clearly laughing at the poetic justice of Emmeline’s early death. “Buck said [Emmeline] could rattle off poetry like nothing. She didn’t ever have to stop to think.” Huck’s tone is one of admiration for Emmeline’s ability. Twain knows that one cannot “rattle off” good poetry and that “stopping to think” is necessary; he is laughing at Emmeline’s verse-writing abilities. “Next Sunday we all went to church…The men took their guns along…It was pretty ornery preaching – all about brotherly love, and such-like tiresomeness; but everybody said it was a good sermon, and they all talked it over going home, and had such a powerful lot to say about faith, and good works…” Huck is simply telling what happened, his reaction to it, and the reactions of the Grangerfords. Twain is conscious of many ironies: • The men took their guns to church to hear a sermon about brotherly love. • Although Huck found the sermon tiresome and ornery, he was the most civilized and religious person in the audience. The butt of the criticism here is not only the Grangerfords but also the church, for it is implied that the church is lacking in true vitality. “…There weren’t anybody at the church, except maybe a hog or two…If you notice, most folks don’t go to church only when they’ve got to; but a hog is different.” Again, Huck mainly reports the facts as he observes them. Twain, however, is clearly implying that so far as going to church is concerned, hogs are more faithful than human beings. Conventions: Our assessment of them depends on how we choose to express individuality. A student who expresses individuality through unconventional dress might regard high school standards of dress as a restriction of freedom. A student who expresses individuality in some other way might not object to such standards at all. Which conventions are socially necessary.? Which are merely an attempt by some dominant social group to impose its standards on everyone? In the mistaken belief that the superficial societal conventions of his day are synonymous with the values of civilization, Huck never realizes that his basic integrity and his compassion reveal him as a truly civilized human being.