Huck Finn

advertisement

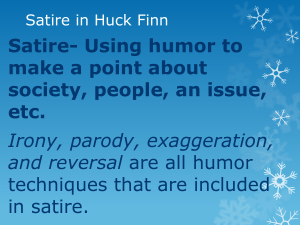

Notes adapted from Joseph Claro in “Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn,” Barron’s Educational Series; and Ronald Goodrich in “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” Living Literature Series. The following is satire on the society in which Twain grew up. Twain grew up in a society that had high regard for families like the Grangerfords: As an adult, Twain felt contempt for people who used a family tree to hide inner decay. Huck describes the decorations in loving detail; yet, they are in pretty poor taste. Emmeline’s drawings are dark and gloomy – they are also maudlin and overly sentimental. “Ode to Stephen Dowling Bots,” the annual ritual on the dead girl’s birthday – it’s all very comical. “Everybody was sorry [Emmeline Grangerford] died…but I reckon, that with her disposition, she was having a better time in the graveyard.” Huck is naïve and means this statement literally: Emmeline doted on death and therefore would presumably be happiest among the dead. Twain, in contrast, is clearly laughing at the poetic justice of Emmeline’s early death. “Buck said [Emmeline] could rattle off poetry like nothing. She didn’t ever have to stop to think.” Huck’s tone is one of admiration for Emmeline’s ability. Twain knows that one cannot “rattle off” good poetry and that “stopping to think” is necessary; he is laughing at Emmeline’s verse-writing abilities. Huck’s description of the Grangerfords show how upright, admirable, and aristocratic they are: Twain uses this as bitter sarcasm. The Grangerfords start to appear silly – the feud, etc. How intelligent can they be? How admirable is pride when it leads to senseless death? What kind of people teach their children to accept murder as normal? And how can Buck so revere the Shepherdsons? Is this a game? “Next Sunday we all went to church…The men took their guns along…It was pretty ornery preaching – all about brotherly love, and such-like tiresomeness; but everybody said it was a good sermon, and they all talked it over going home, and had such a powerful lot to say about faith, and good works…” Huck is simply telling what happened, his reaction to it, and the reactions of the Grangerfords. Twain is conscious of many ironies: • The men took their guns to church to hear a sermon about brotherly love. • Although Huck found the sermon tiresome and ornery, he was the most civilized and religious person in the audience. The butt of the criticism here is not only the Grangerfords but also the church, for it is implied that the church is lacking in true vitality. “…There weren’t anybody at the church, except maybe a hog or two…If you notice, most folks don’t go to church only when they’ve got to; but a hog is different.” Again, Huck mainly reports the facts as he observes them. Twain, however, is clearly implying that so far as going to church is concerned, hogs are more faithful than these human beings. By the end of the chapter, even Huck is disgusted, and he’s too sickened by the details to share them. Huck is slow to learn this lesson – many of the people he looks up to are not as admirable as he thinks. And he is very happy to get back to the world of the raft with Jim. There isn’t any explanation for why Twain seems to have forgotten about Jim during this extended portion of the novel. Ch. 19 begins with one of the longest descriptions in the book of the beauty of being on the river. Huck and Jim meet the Duke and Dauphin (doe-fan)/King Temperance revival: religious meeting at which drinking alcohol is condemned. Jour printer: a printer who travels around looking for a day’s work (“jour” is the French word for “day”) Patent medicine: usually a concoction of any ingredients available, accompanied by wild claims for what it will cure. Mesmerism: hypnotism Phrenology: the study of personality as it is revealed by bumps on the skull. Laying on of hands: curing people by touching them and praying aloud. The king comes up with a plan that will allow them to travel the river during the day that involves some unpleasant news for Jim. The Duke’s Shakespearean soliloquy is a piece of comedy in its own right. As fake as it is, Huck is impressed. David Garrick and Edmund Kean were real people, the most famous Shakespearean actors of the 19th century. In town, Huck finds himself in surroundings that are directly opposite the ones he just left with the Grangerfords – yet no more admirable. Huck witnesses the coldblooded shooting of a toughtalking drunk who insults a well-dressed man named Colonel Sherburn, who shows a little patience by giving the man a warning but then kills him when the warning is ignored. The townsfolks’ reaction? To fight over “front-row seats” to see the dead body, and to revel in a reenactment of the shooting. Only then to they decide to lynch Sherburn. “The average man’s a coward…The average man don’t like trouble and danger.” This is Sherburn, who has just shot and killed a man in cold blood and is contemptuous of the crowd that has come to lynch him. It is a mob comprised of average men who lack the courage to face a single true man in daylight. Without masks or the cover of darkness, they are cowards. The speech reflects Twain’s own attitude toward people in general. The human race is, for the most part, made up of fools and knaves. Note Sherburn refers to the average man; he (and Twain) imply the existence of true men who can rise above the average. We can see Jim as a true man of natural nobility; Huck himself is growing into such a man.