No Opt Out final - Marshall Middle School

advertisement

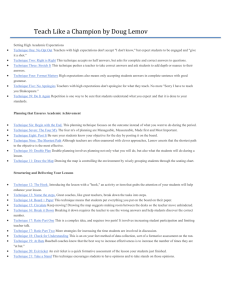

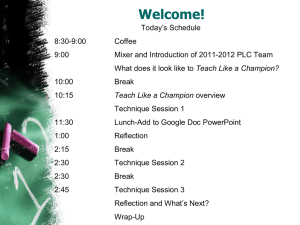

+ No Opt Out Teach Like a Champion by Doug Lemov + Marshall, GATE, Professional-Development Goal 2012-13 Each Year, Marshall Teachers choose a professional-development goal which will be the focus of yearlong professional development. Our 2012-2013 staff development plan includes several steps: 1. Deliberation and choice of a differentiated strategy deemed to be the most beneficial to our gifted student population. We chose Socratic questioning strategies with an emphasis on the “No Op-out Strategy” as researched and described by Doug Lemov in Teach Like a Champion. 2. Establish methods and practices for implementation. 3. Collaborate and assess implementation for best practices throughout and at the completion of the school year. We invite and strongly encourage parents to read and practice the strategies presented in Teach Like a Champion, especially chapter one, which is the focus of our staff development this academic year. + Setting High Academic Expectations “One consistent finding of all academic research is that high expectations are the most reliable driver of high student achievement, even in students who do not have a history of successful achievement (27).” Contrary to common myths about educational success, Lemov’s research-data argues that teachers, not socio-economic factors, make the difference. Lemov’s findings can be boiled down to one statement: effective educators set, maintain and achieve high expectations for all their students. “No Opt Out” is a system of techniques which Lemov terms, “concrete actionable ways teachers… demonstrate high expectations” in their daily classroom interactions. The No Opt Out system consists of five indivisible techniques, which are No Opt Out, Right is Right, Stretch It, Format Matters, and Without Apology. + The Foundation of Learning A teacher’s first priority is always to connect with each child and foster a safe and nurturing environment for all students. Marshall teachers believe that no learning can take place unless students feel valued, safe and important. We know that the road to all learning begins in a classroom community where students know that they are more important than test scores or academic concepts. Therefore, the following instructional practices (No Opt Out, Right is Right, and Format Matters) are always subordinate to the affective relationship between the instructor and the student. + No Opt Out: the foundation of high expectations KEY IDEA: A sequence that begins with a student unable to answer a question should end with the student answering that question a often as possible (28). RATIONALE: When a student replies, “I don’t know”, sucks in their breath and looks out the window, it is a critical moment. Students all too commonly use this approach to push back on teachers when they are unwilling to try, have a lack of knowledge, or a combination of the two. And all too often, it works. Reluctant students quickly come to realize that “I don’t know” is the Rosetta stone of work avoidance. Fewer students will persist in this avoidance behavior once the teacher has made their expectations clear, demonstrated a nurturing environment and the teacher has shown their persistence. + Four Basic Formats Format One: You provide the answer; the student repeats the answer. Format Three: You provide a clue; the student uses the clue to find the answer. Format Two: Another student provides the answer; the initial student repeats the answer. Another variation of this method is to ask the whole class to provide the answer, and then the initial student repeats it. Format Four: Another student provides a clue; the initial student uses it to find the answer. + Right Is Right KEY IDEA: Set and defend a high standard of correctness in your classroom (35). RATIONALE: Many teachers respond to almost correct answers by rounding up, that is, responding “correct” and filling in the missing information or correcting the minor inaccuracies presented by the initial student. In this way, the teacher has set a low standard for correctness and explicitly told the class that they can be right, even when they are not. Just as important, the teacher has crowded out students’ own thinking, doing cognitive work that students could do themselves. + Four, Right-is-Right Strategies Hold out for all the way: Great teachers wait for and request the complete answer. Great teachers may say, “I like what you’ve said. Can you get us the rest of the way? We’re almost there. Can you get us the rest of the way?” Answer the question: Students learn quickly that if you don’t know the answer to the question asked, you can usually get by by answering a different question, especially if it is heartfelt and emotional. A great teacher will redirect the initial student to the question asked. Right Answer, Right Time: Some students want to show you and the class how smart they are by getting ahead of your questions. This is risky to accept answers out of sequence since it deprives the rest of the class the benefit of going through the sequence. It is likely the majority of students need all the steps in sequence. Great teachers accept the right answer at the right time. Use Technical Language: Good teachers get students to give effective responses using vernacular they are comfortable with. Great teachers get students to use precise technical terms in the academic language of each discipline. + Stretch It KEY IDEA: The sequence of learning does not end with a right answer; reward the right answer with follow-up questions that extend knowledge and test for reliability. This technique is especially important for differentiating instruction (41). RATIONALE: This technique yields two benefits. First, it allows the teacher to make sure the students truly understand the content or skill and that the response was not just a fluke. Second, when mastery has in fact occurred, stretch it enables the teacher to give students exciting ways to push ahead, apply their knowledge in new settings, think on their feet, and tackle harder questions. DIFFERENTATION: Stretch it is especially important for differentiating instruction. By tailoring questions to individual students, great teachers can meet students where they are and push them in a way that’s directly responsive to what they’ve shown they can do already. + Ways to Stretch It Ask how or Why. Ask for another way to answer. Ask for a better word. Ask for evidence. Ask students to intergrade a related skill. Ask students to apply the same skill in a new setting. + Format Matters KEY IDEA: It’s not just what students say that matters but how they communicate it. To succeed, students must take their knowledge and express it in the academic language of opportunity. They must also master patterns of discourse in order to succeed in an academic setting (51). RATIONALE: Students must take their knowledge and express it in a variety of clear and effective formats to fit the demands of the situation and of society. It is not just what students say, but how they say it. The complete sentence, the essay and academic conversation, including correct syntax and subject-verb agreement, constitute the essentials of success. + Format Matters Grammatical Format. Complete Sentence Format. Patterns of Discourse. Audible Format. + Without Apologies KEY IDEA: Great teachers make no apologies for teaching rigorous, worthy content. Great teachers set high expectations and never apologize for holding students accountable for accuracy, format, and high academic vocabulary. RATIONALLE: Teachers often apologize for content by saying things like, “I know this stuff is boring, but let’s just get through it.” Or, “The State requires you to learn this.” Sometimes teachers apologize for students by saying, “These students, will never get this content. I need to dilute it to the basics. “ Great teachers never apologize. + Alternatives to Apologies Instead of apologizing, great teachers may use the following alternatives. Use positive feedback on the students’ ability to master the topic. Reassure students that you (the teacher) are with them all the way in sticking to the topic until mastered. Call out the future benefits of the knowledge they will attain. Be upfront that the topic is challenging, and say that you (the teacher) are positive they have the ability to master it. + Important Misconception The correlation between success on even more straightforward assessments and ultimate academic success should be instructive to us. I often meet educators who take it as an article of faith and basic skills work in tension with higher-order thinking. That is, when you teach students to, say, memorize their multiplication tables, you are not only failing to foster more abstract and deeper knowledge but are interfering with it. This is illogical and, interestingly, one of the tenants of American education not shared by most of the educational systems of Asia, especially those that are the highest performing public school systems in the world. Those nations are more likely to see the foundational skills like memorizing multiplication tables enables higher-order thinking and deeper insight because they free students from having to use up their cognitive processing capacity in more basic calculations. To have the insight to observe that a more abstract principle is at work in a problem or that there is another way to solve it, you cannot be concentrating on the computation. That part has to happen with automaticity so that as much of your processing capacity as possible can remain free to reflect on what you’re doing. The more proficient you are at the lower-order skills, the more proficient you can become at higher order skills (18). Such basic skills extend to multiplication facts, punctuation, parts of speech, sentence structure, spelling, academic vocabulary, basic writing formats, rhetorical devices and beyond. Only when students achieve automaticity, they are freed up to experience “higher order thinking.” + Next Steps: Planning for success. Next year, Marshall GATE and Seminar teachers will focus our professional development goals on planning for academic success. We will focus on the following six key concepts. Beginning with the end in mind means that all learning objectives and experiences should be designed to meet specific state standards. 4 MS: A great lesson objective should be manageable, measurable, made first, and most important on the path to college. Post it so it is visible for all to see, preferably in the same place every day on the white board. Opt for the shortest path to the objective. Double plan, which means each learning objective should include what the students will be doing during each phase of the lesson as well as the instructor. Reflect and refine each lesson and unit by carefully analyzing what worked and what you can do better next time. Evaluate weather you need to reteach any concepts or skills.