illiberalism

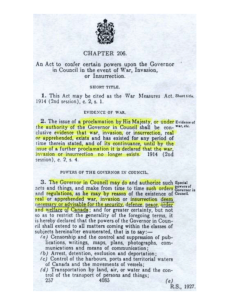

advertisement

Illiberalism Doukhobors • The Doukhobors are a group of Russian language-speaking religious • • • • dissenters who migrated to Canada in 1899. Today there are between 30,000 and 40,000 Doukhobors in Canada, and another 30,000 in Russia. They had been persecuted in tsarist Russia for their religious beliefs, which included the conviction that pacifism and non-compliance with militarism is essential to Christian practice because the law of God is greater than the laws of a secular state. These convictions culminated in the 1895 Burning of Arms in Russia, when Doukhobors destroyed their weapons and refused, despite tsarist persecutions, to serve in the Russian army. This protest might have been the first organized pacifist group protest in modern history. • The Doukhobors practice a form of Christianity and • • believe that Jesus Christ is a spiritually advanced teacher and example to others. They also believe that people are capable of divine reason and can spiritually develop without the help of intermediaries. For them, therefore, there is no need for priests, religious ceremonies, spiritual symbols or temples of worship, although there have been leaders among the Doukhobors who have exercised considerable authority. • The Doukhobors have at times participated in communal living and, like the Mennonite, Quaker and Hutterite groups, in the practices of pacificism, hard work and simplicity in all things. • Initially, Doukhobors were permitted to register • • for individual homesteads but to live communally, and they received concessions regarding education and military service. Frank Oliver, who succeeded Clifford Sifton as minister of the interior in 1905, interpreted the Dominion Lands Act more strictly. When Doukhobors refused to swear an oath of allegiance - a condition for the final granting of homestead titles - their homestead entries were cancelled. • In 1908 Verigin led most of his followers to • • • southern British Columbia, where he bought land and established a self-contained community of 6000. Some Doukhobors split off to their own farms and became Independents. A tiny splinter, the radical Sons of Freedom (founded in 1902 in Saskatchewan), burnt several schools in a dispute with BC over education. Many in this group were later imprisoned for nude protest parades Japanese Canadian Internment • The Japanese Canadian internment was the forced removal and of more than 22,000 Japanese Canadians during the Second World War by the government of Canada. • Following the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, prominent British Columbians, including members of municipal government offices, local newspapers and businesses called for the internment of the Japanese. • In British Columbia, there were fears that some Japanese who worked in the fishing industry were charting the coastline for the Japanese navy, acting as spies on Canada's military. • Military and Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) authorities felt the public's fears were unwarranted, but the public opinion quickly pushed the government to act. • Canadian Pacific Railway fired all the Japanese workers, • • and most other Canadian companies did the same. Japanese fishing boats were first confined to port, and eventually, the Canadian navy seized 1,200 of these vessels. Many boats were damaged, and over one hundred sank. • In January 1942, a "protected" 100-mile (160 km) wide strip up the Pacific coast was created, and any men of Japanese descent between the ages of 18 and 45 were removed and taken to road camps in the British Columbian interior, to sugar beet projects on the Prairies, or to internment in a POW camp in Ontario. • Despite the 100-mile quarantine, a few men at the McGillivray Falls, just outside the quarantine zone, were employed at a logging operation at Devine, near D'Arcy, British Columbia, which is inside the quarantine zone, while those in the other Lillooet Country found employment with farms, stores, and the railway. • Tashme, on Highway 3 just east of Hope, among the most notorious of the camps for harsh conditions, was just outside of the exclusion zone. • All others, including Slocan, were in the Kootenay Country in southeastern British Columbia. • Most people of the 21,500 Japanese descent who lived in British Columbia were • • • • • • naturalized or native-born citizens. Those unwilling to live in internment camps or relocation centres faced the possibility of deportation to Japan. On February 24, 1942 an Order-in-Council passed under the War Measures Act giving the federal government the power to intern all "persons of Japanese racial origin.” In early March, all ethnic Japanese people were ordered out of the protected area, and a daytime-only curfew was imposed on them. Some of those brought inland were kept in animal stalls for the Pacific National Exhibition at Hastings Park, in Vancouver for months. They were then moved to ten camps in or near inland British Columbia towns, sometimes separating husbands from their wives and families. However, four of those camps in the Lillooet area and another at Christina Lake were formally "self-supporting projects" (also called "relocation centres") which housed selected middle and upper class families and others not deemed as much a threat to public safety. • Officially, those living in "relocation camps" were not legally interned - they could leave, • so long as they had permission - however, they were not legally allowed to work or attend school outside the camps. Since the majority of Japanese Canadians had little property aside from their (confiscated) houses, these restrictions left most with no opportunity to survive outside the camps. • "It is the government’s plan to get these people out of B.C. as fast as possible. It is my personal intention, as long as I remain in public life, to see they never come back here. Let our slogan be for British Columbia: No Japs from the Rockies to the seas.'” Ian Mackenzie, MP • In 1943, the Canadian "Custodian of Aliens" began to sell the possessions of Japanese • • • Canadians without the owners' permission. The Custodian of Aliens held auctions for these items, ranging from farm land and houses to people's clothing. They were sold quickly at prices below market value. Funds raised went towards the fees of realtors and auctioneers, and storage/handling charges, and Japanese owners rarely received much income from the sales. Unlike official prisoners of war who, according to Geneva Convention, didn't have to pay their living expenses, Japanese internees did. • After the victory over Japan, the federal government moved to evacuate Japanese • • • • • • • • Canadians from British Columbia all together. Evacuees were given the choice between deportation to Japan or transfer to areas east of the Rocky Mountains. The majority opted to remain in Canada, and moved to Ontario, Québec and the Prairie provinces. Following public protest, the order-in-council that authorized the forced deportation was challenged on the basis that the forced deportation of the Japanese was a crime against humanity and that a citizen could not be deported from their own country. The Prime Minister referred the matter to the Supreme Court. In a five to two decision, the Court held that the law was valid. Three of the five found that the order was entirely valid. The other two found that the provision including both women and children as threats to national security was invalid. In 1947 the deportation order was repealed, after 4,000 Japanese Canadians had already left the country. On April 1, 1949, Japanese Canadians regained their freedom to live anywhere in Canada. October Crisis FLQ • The October Crisis was a series of dramatic events triggered by two terrorist kidnappings of government officials by members of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) in the province of Quebec, Canada, in October 1970, which ultimately resulted in a brief invocation of the War Measures Act by Prime Minister Pierre E. Trudeau and the deployment of the national army in Quebec and in the national capital Ottawa. • From 1963 to 1970 the Quebec nationalist group Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) had exploded over 95 bombs. • While mailboxes, particularly in the affluent and predominantly Anglophone city of Westmount, were common targets, the largest single bombing was of the Montreal Stock Exchange on February 13, 1969, which caused extensive damage and injured 27 people. • Other targets included Montreal City Hall, RCMP recruitment offices, railroad tracks, and army installations. • FLQ members, in a strategic move, had stolen several tons of dynamite from military and industrial sites. Financed by bank robberies, they threatened the public through their official communication organ, known as La Cognée, that more attacks were to come. Timeline • October 5: Montreal, Quebec: Members of the "Liberation • • • Cell" of the FLQ kidnap British Trade Commissioner James Cross. This was followed by a communiqué to the authorities that contained the kidnappers' demands, which included the exchange of Cross for "political prisoners", a number of convicted or detained FLQ terrorists, and the CBC broadcast of the FLQ Manifesto. The terms of the ransom note were the same as those found in June for the planned kidnapping of the U.S. consul. At the time, the police did not connect the two. • October 8: Broadcast of the FLQ Manifesto in all French- and English-speaking media outlets in Quebec. • October 10: Montreal, Quebec: Members of the Chenier Cell approach the home of the Vice-Premier and Minister of Labour of the province of Quebec, Pierre Laporte, while he was playing football with his nephew. Members of the "Chenier cell" of the FLQ kidnap Laporte. • October 11: The CBC broadcasts a letter from captivity from Pierre Laporte to the Premier of Quebec, Robert Bourassa. • October 13: Prime Minister Trudeau is interviewed by the CBC in respect of the military presence. In a combative interview, Trudeau asks the reporter what he would do in his place, and when asked how far he would go replies "Just watch me". • October 15: Quebec City: The Government of Quebec, solely responsible for law and order, formally requisitions the intervention of the Canadian army in "aid of the civil power", as is its right alone under the National Defence Act. • All three opposition parties, including the Parti Québécois rise in the National Assembly and agree with the decision. • On the same day, separatist groups are permitted to speak at the Université de Montréal and Robert Lemieux organizes 3,000 student rally in Paul Sauve Arena to show support for the FLQ; labour leader Michel Chartrand announces that popular support for FLQ is rising and "We are going to win because there are more boys ready to shoot members of Parliament than there are policemen." • The rally frightens many Canadians, who view it as a possible prelude to outright insurrection in Quebec; • October 16: Premier Bourassa formally requests that the • • • government of Canada grant the government of Quebec "emergency powers" that allow them to "apprehend and keep in custody" individuals. This resulted in the implementation of the War Measures Act, which allowed the suspension of habeas corpus, giving wide-reaching powers of arrest to police. The City of Montreal had already made such a request the day before. These measures came into effect at 4:00 a.m. Prime Minister Trudeau made a broadcast announcing the imposition of the War Measures Act. • The provisions took effect at 4:00 a.m., and • • soon, hundreds of suspected FLQ members and sympathizers were rousted out of bed and hauled into custody. At the time, opinion polls in Quebec and the rest of Canada showed overwhelming support for the War Measures Act. Since then, however, the government's use of the War Measures Act in peacetime has been a subject of debate in Canada as it gave police sweeping powers of arrest and detention. • Outside Quebec, mainly in the Ottawa area, the • federal government deployed troops under its own authority to guard federal offices and employees. The combination of the increased powers of arrest granted by the War Measures Act and the military deployment requisitioned and controlled by the government of Quebec, gave every appearance that martial law had been imposed. • A significant difference, however, is that the • • military remained in a support role to the civil authorities (in this case, Quebec authorities) and never had a judicial role. Nevertheless, the sight of tanks on the lawns of the federal parliament was disconcerting to many Canadians. Moreover, police officials sometimes abused their powers and detained without cause prominent artists and intellectuals associated with the sovereignty movement