Social Housing in Spain

advertisement

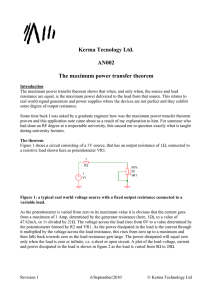

Brazil-EU Dialogue seminar on low income housing finance and subsidies Social Housing in Spain Baralides Alberdi 25/09/2014 1 • • • • • • • Introduction Historical development Structure of social housing Funding of social housing Prices and rents Access and allocation Current policies environment 2 Social housing and comparison with other tenures Owner occupation % 1960 51 1970 64 1981 73 1991 78 2001 82 2011 79 Source: INE Census 1960-2011 Rental All % 45 32 23 16 11 13,5 Private % 43 30 21 15 10 11,5 Social % 2 2 2 1 1 2 Others Total % 4 4 4 6 7 8 ms 7.0 8.5 10.4 11.8 14.2 18.1 Housing policy fundamentally emphasizes home ownership. Access to rented accommodation residual both through the public and the private sector. Owner occupied sector, up to 82% in 2001, including market housing but also social housing for ownership. The rented sector, 13%, divided into private rented and social rented, only 2% of the total stock. 3 Social housing and comparison with other tenures • Two kinds of social housing – Officially protected housing (VPO), peculiar compare to social housing models in EU countries in that it is provided almost entirely for owneroccupation. Only a small proportion is built and offered for rent. – Social rented housing, which is comparable to what is normally called social housing elsewhere in Europe. 4 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 New construction: market and social housing 700000 600000 500000 400000 300000 200000 100000 0 Market Housing VPO Social Housing 5 Historical developments • The 1978 post-Franco constitution divided Spain into 17 regions, each with its own legislative body and autonomous governments that control most of their own housing policies. Central governments only retain control over some of the design of fiscal and social housing policy through a series of national housing plans that have been rooted in two principles: • One is the public financing for VPO social housing built by private developers. • The other is the temporary nature of the protection regime for such dwellings, which allows them to eventually move into the free housing market. • Given the multiple and decentralised decision-making processes, the implementation of housing policy in Spain is not always coherent or straightforward. 6 Structure of social housing • • • • The development, construction and rehabilitation of VPO housing is open to a wide spectrum of providers including the State, regional governments, municipalities, public developers, mixed public-private companies, commercial developers, associations, co-operatives, not-for profit organizations, and private individuals provided they fulfill the criteria established by law. Once the VPO houses are built they are sold, making the property and its management the private responsibility of the owners. Dwellings maintain their social character for a limited period of time (20 years) after which they can be traded at market prices. Within the 20-year period, re-sale prices are controlled and owners who sell must repay subsidies. Despite this requirement, owners can make substantial capital gains in the long run. Only a small percentage of the social VPO houses built are rented and those are owned and managed by specialized institutions. Since the 1980s, most regional governments and municipalities have created public housing corporations to deal with this rented stock. Professionalism varies greatly among different companies and most providers administer, maintain and repair existing stock; select its beneficiaries; enforce eligibility conditions including the possible rotation of tenants. Also are fully or partially responsible for developing the land (normally supplied free by the municipality), and engaging a private contractor to construct the dwelling. 7 Funding VPO social housing • The main form of subsidy is through the provision of free or cheap land (the cost of land cannot make up more than 15% of the final price of the unit) for construction by municipal landowners. • The additional cost of VPO social housing are financed through two avenues: the public budget and the banking system. • Some of the social housing built during the 1960s, through to the 80s was partially funded through the public budget. It also provided funds for upfront subsidies to lower income households. The public budget also funded the interest rates subsidies embedded in VPO loans. The fall in interest rates has reduced the importance of such subsidies and state funds for housing go now mainly to demand side subsidies which had been increasingly eliminated since 2010. • The other major source of funding is the banking system. Since the mid1970s, mortgage funding was the responsibility of banks and savings banks, including mortgages for VPO dwellings. The state contracts with these private credit institutions, which in turn provide loans on favourable conditions. 8 Taxes and subsidies • Since the 1970s, owner-occupiers (including owners of VPO social housing) have been able to deduct a proportion of mortgage loan payments from income for tax purposes. • Over the years, there were changes to the details of the scheme and it had been eliminated since January 2013, but only for new mortgages. • VPO social housing also benefits from a range of upfront subsidies and grants. They vary by regions but are minor compared to the mortgage tax deductions. • Since 1995, VPO social housing has been eligible for a reduced rate of VAT (4% as opposed to 10% for other housing). 9 Nature and scope of rental assistance • The state budget has always contained some funding for the construction of social housing for rent, but the amount was insignificant until 2004. • In that year, the new socialist government offered developers a 20% upfront subsidy and a 50% interest-rate subsidy for building rental dwellings, on the condition that rents were kept low. • In 2008 a housing allowance was introduced for tenants of certain age and income. It was revoked in December 2011 by the new conservative government. • Many autonomous governments have their own tax deductions for tenants, which have created inequalities between people living in different parts of Spain. 10 VPO prices and rents • We can compare VPO and market house prices. Converging since the global financial crisis hit. Gone from 50% of the market price in 2007 to 75% in 2014. • No statistics available for social rents. For units of similar size and quality, social rents are estimated to be around 50% of private rents. 2150 1950 1750 1550 1350 1150 950 750 1º2º3º4º1º2º3º4º1º2º3º4º 1º2º3º4º1º 2º3º4º1º 2º3º4º1º 2º3º4º1º 2º3º4º1º2º3º4º1º2º 2005 Source: Ministry of Public Works 2006 2007 2008 2009 Market €m2 2010 VPO €m2 2011 2012 2013 2014 11 Access and allocation of VPO social housing Eligibility criteria vary somewhat by autonomous government but in general require that the purchaser: • Not own or have a permanent right to use another dwelling • Not have obtained financing under the Housing Plan over the previous 10 years • Have an income below a certain level, and • Have lived in the area for at least two years Broadly speaking, some 80% of households have an income below the ceiling for access to some form of VPO social housing. Although VPO social housing continues to be built, its effectiveness has been extensively questioned. During the last 40 years more than 4 million of VPO social housing units have been produced. This significant amount of stock has not been reusable as a buffer to resolve the new problems of accessibility as most was sold to owner-occupiers. Owners can them easily “reclassify” these VPO dwellings and sell them at market prices, producing considerable transfers of income for themselves. These houses also pose a problem of equality in their distribution. Although eligibility criteria are applied, there is no legally required ranking procedure, meaning that developers themselves can select buyers from among eligible households. It is in the developers interest to sell to creditworthy buyers because the buyer assumes a portion of the developers loan and the lending bank must agree to accept the transfer. These factors mean that households with low incomes or more precarious economic situations are vulnerable and systematically disadvantaged . 12 Effects of the global financial crisis • The specific housing circumstances of the country at present are the result of a combination of the global financial crisis, tightened mortgage regulations, increased unemployment and years of oversupply. • When the crisis hit, credit dried up, the massive housing boom ended abruptly, the amount of vacant stock increased dramatically and it was estimated that an additional 1 million empty houses were added to the stock. • Developers were left with blocks of unsold properties and massive debts. Since 2008, the government has been attempting to promote the sale of this vacant stock. • The crisis has also resulted in a rapid increase in the number of bad loans and repossessions, making Spanish banks the largest property owners in the country. At the moment, the biggest banks are trying to sell as many houses as they can, as well as to rent below market prices. And at the end of 2012 a “bad bank” was created to absorb part of it. 13 The future of the sector • • The future of social housing is bleak. After the crisis hit, most demand-side subsidies were reduced and many have now disappear entirely. The number of new VPO social units have plummeted. Social housing, both VPO and rented, is increasingly disappearing and social housing developers try to sell their already small stocks to get cash to maintain their administrative structures. The overall shape of the puzzle remains unclear: there are many actors with vested interest involved in the social housing sector, but it lacks a leading voice or clearcut policy direction. 90000 VPO housing starts by tenure 80000 70000 60000 50000 40000 30000 20000 10000 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Owner-occupation 2010 2011 2012 2013 Rented 14