Chapter 13.3 - VCE Biology Units 1 and 2

VCE Biology Unit 2

Area of Study 01

Adaptations of Organisms

Chapter 13.3

Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Desert

• Low rainfall

• High level of evaporation

• Hot (Australia, Sahara) or cold (Central Asia,

South America, Antarctica)

Antarctica largest desert – 50 mm rain per year,

14,245,000 km 2

Sahara largest ‘hot’ desert 9,000,000 km 2

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Australia has greatest percentage of continent as desert/semi-arid (44% and 37% respectively)

• High temperature

• High solar radiation

• Low rainfall

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Animals

Stress

– Body temperature

– H

2

O

– Salt balance

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Survival

• Regulate these factors or tolerate extreme fluctuations

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Temperature regulation assisted by

• Behaviour that increases or decreases heat exchange with external environment.

• Circulatory adjustments alter blood flow through skin – alters heat exchange

• Increase or decrease production of metabolic heat.

• Evaporative cooling through sweating or panting (trade off with water loss)

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Reptiles

• Behaviour changes most important to regulate rate of heat exchange

Behavioural Thermoregulation

• e.g. Australian agamid lizard, Shark Bay, WA

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

• Some iguanid lizards maintain body temperature at ~38°C for extended periods.

• Desert snakes and tortoises maintain body temperature at ~30°C adopt nocturnal behaviour during summer

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Sleep through bad times

Some animals survive harsh conditions by going into torpor or hibernation. Torpor (fish, frogs, lizards, birds, bats and mice) allow body temperature to decrease and become inactive or dormant.

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Frogs burrow into sand during dry season and become dormant

Water holding frog burrows deep into sand and makes a cocoon from its cast off skin and can survive for months.

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Escaping the cold – hibernation

Do any Australian animals hibernate?

Short beaked echidna goes into torpor underground to escape winter/snow in southern mountains.

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Hibernation

• Long term torpor

• Happens at onset of winter

• In den/burrow

• Decrease energy requirements (do not eat)

• Hibernation saves 60% of an animal’s annual energy requirement

• Some evidence suggest animals may live longer.

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Triggers for Hibernation. One of more factors

• Scarcity of food

• Decrease in temperature

• Endocrine response to change in daily light cycle.

• Mammals and birds enter hibernation from sleep and involve decrease of body temperature close to ambient, but never below zero

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Triggers for Hibernation. One of more factors

• Burrows/dens temperature constant

• Metabolism decreased (indicated by decrease in

O

2 consumption – leads to fall in body temperature

• Heart rate decreases to around 3 to 10 beats per minute

• Respiration decrease

• Slow breathing with long periods of no breathing

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

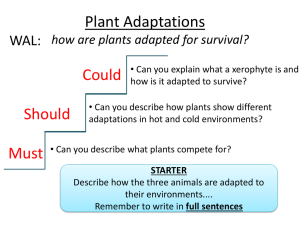

Plants in arid environments

Adaptations for reducing water loss

• Xenophytes (‘lovers of dryness’)

• Two types

– Flesh succulent plants (e.g. cacti)

– Hard-leaved plants called sclerophylls

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Adaptations for reducing water loss

• Thick waxy cuticle

• Hairs covering leaves

• Few stomata

• Sunken or protected stomata

• Reduced leaf surface area to volume

• Orientation of leaves away from direct rays of sun

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Leaf cuticle and hairs

• Xerophytes have thick waxy cuticle impermeable to water

• Hairs reduce leaf temperature and water loss

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Distribution of Stomata

• Fewer stomata. Number and size varies between species.

• Pits surrounded by hairs

• Maybe closed at hottest time of day

• Succulents close stomata at day and open at night for uptake of CO

2

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Reduced surface area and leaf orientation

• Surface area low to reduce water loss by transpiration

• Some species have needle like leaves (e.g.

Hakea and cacti)

• Eucalypts’ leaves hang vertically. Stomata and photosynthetic cells on both sides of leaves

(i.e. isobilateral).

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Coping with salinity on land

• [Salt] can be 1/10 of sea water. Combined with high temperatures and low rain fall.

• Creates osmotic stress due to lack of water

Chapter 13.3 Living in extreme terrestrial environments

Halophyte adaptations

• Halophytes (‘lovers of salt’) tolerant to high levels of salt and many are succulents

• Regulate water loss and salt accumulation in leaves from transpiration of water from roots.