the Power Point on Logical Fallacies

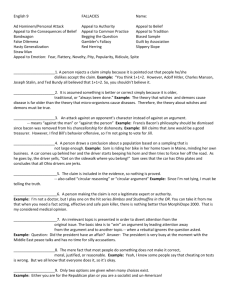

advertisement

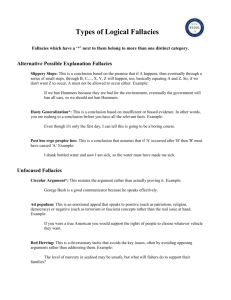

CONSTRUCTING REASONABLE ARGUMENTS MODES OF PERSUASION ETHOS • An appeal to the authority or character of the presenter (this is where the word “ethics” comes from) • You can be the authority • You can have the experience necessary • You can “borrow” the authority through the application of “logos” LOGOS • An appeal to logic or reason (this is where the word “logic” comes from) • You must provide evidence • You must interpret that evidence • You must show the sources of your evidence • You must do this clearly PATHOS • An appeal to emotion (this is where the words “sympathy” and “pathetic” come from) • You can use a powerful analogy (like Jensen’s space aliens) • You can use a vision of the future (like Carly Lettero’s vision of her own death) • But you must avoid manipulation, and you must also employ logos. • This works best when employed as a passionate style, rather than as a substitute for substance. LOGICAL FALLACIES THE TOP TEN HASTY GENERALIZATIONS • These arguments are based on atypical, irrelevant, or inaccurate evidence—usually because the sample from which the evidence comes is too small • “Of course our students are physically fit; just look at the success of our sports teams!” • “Today was colder than yesterday; climate change is a fraud!” • “There’s no absolute agreement on climate change; therefore, it doesn’t exist.” • “All poets are suicidal. Look at Dorothy Parker’s poems—one of them is all about committing suicide.” POST HOC (FAULTY CAUSE AND EFFECT) • These arguments are based on the assumption that if event B happens after event A, then event B must be caused by event A. • “Tourism in this city started to decline right after Mayor Scott was elected. To save our tourist industry, let's replace her now!” • “The Climate started to warm after the Industrial Revolution began. Therefore, Climate Change is caused by the Industrial Revolution.” • “Margtaret Atwood wrote much of her poetry after Duncan Campbell Scott; therefore, her poetry must be influenced by his.” REDUCTIVE REASONING • This is an attempt to explain a complex effect through a simple cause (oversimplification). • “My aunt lived to be ninety-four. She drank a glass of beer every day. If we all drink a glass of beer every day, we will live to be ninety-four.” • “Wind turbines use no fossil fuels to produce energy. Therefore, we can avoid Peak Oil by switching to wind energy.” • “Ambrose Bierce wrote a story that was sympathetic to a slave-holding plantation-owner. He must have approved of slavery.” FALSE ANALOGIES • This occurs when a writer tries to draw similarities between two things that are so dissimilar that the comparison is absurd. • “Why do I have to take English in order to graduate? I don’t have to buy vegetables to leave the grocery store!” BEGGING THE QUESTION • This one is frequently misinterpreted. What it means is to assume that the point you are arguing is true. If this really were the case, the point would not need arguing. This should not be confused with the attempt to argue something that is incontrovertible. • “Improving public transportation in this city won't solve highway congestion. Even if public transportation is clean, safe, and efficient, people will still prefer to use their cars.” • “In tragedies, people die at the end of the story. The Taming of the Shrew is not a tragedy because no one dies at the end.” CIRCULAR REASONING • The argument consists of stating the conclusion it was meant to support. • “The priest is a good person because he is virtuous.” • “If the story had a different plot, the ending would be different.” AD HOMINEM • This means attacking the person rather than the argument (and was used extensively against Bill Clinton after the Monica Lewinsky scandal). • “We can’t trust Bill Clinton to lead the country; he had an affair with an intern.” • “None of Al Purdy’s poetry is any good; he was an alcoholic.” • a similar fallacy is the “straw man,” where a position is presented in its most extreme form in order to discredit its proponents. FALSE DILEMMA/DICHOTOMTY • This comes from the assumption that there are only a very limited number (usually two) of interpretations or truths. • “Either 1+1=4 or 1+1=5. 1+1 does not equal 4; therefore, 1+1=5.” • “Either we support the death penalty or we allow crime to run rampant.” • “Either we continue with the economy of growth, or we go back to living in caves.” • “Either you’re with us, or you’re against us.” APPEAL TO POPULARITY • This is the “everybody’s doing it, we should too” or “everybody thinks so” argument. I don’t think we need examples here! • Closely related, though, is the appeal to history: because things have always happened this way, they will continue to happen the same way. This is also a form of “post-hoc” argument. Here’s the best (and most frightening) example: “We’ve always been able to use technology to solve our problems before; therefore, we’ll be able to technologically innovate our way out of Climate Change and Peak Oil as well.” NON SEQUITURS • Literally, this means “it does not follow.” It happens when there really isn’t a clear connection between the premise (or starting point of the argument) and the conclusion • “Maria loves college, so she will make a great teacher.” • “Shakespeare wrote lots of great poems, so this poem by Shakespeare must be great.” OTHER FALLACIES TO AVOID: • Appeal to Authority: Just because Dr. Smartypants says it’s true doesn’t mean it is. Make your own argument! • Appeal to Common Practice: aka “the lemming argument.” If everyone jumped off a bridge, would you do it too? • Appeal to Novelty: New is not better; it’s just new. Likewise length; likewise moderate positions. • Appeal to Composition: individuals in a group have characteristics a, b, and c; therefore, the group must have characteristics a, b, and c. (This one leads to –and explains—a great deal of prejudice). THINGS TO REMEMBER • Most of the conclusions included in the examples above could be argued. The problem is that the reasoning provided in these examples is insufficient or not credible. • The best way to "smoke out" unsound reasoning in your own writing is to ask yourself what your argument takes for granted. Remove those assumptions, then rebuild your argument using stronger support--if such support exists.