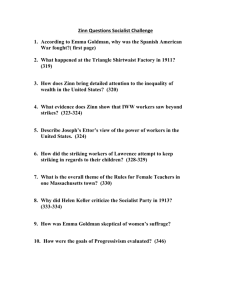

A People`s War? - Gabriel Buelna

advertisement

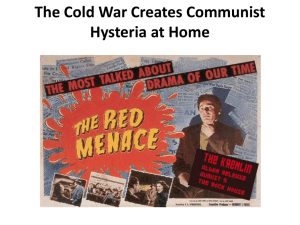

A People’s War? By: Angie Rodriguez Professor Buelna CHS 245 OL Class #14004 Opener Zinn opens Chapter 16 (“A People’s War?”) of A People’s History of the United States with a quote released by the Communist Party in the United States in 1939: “We, the governments of Great Britain and the United States, in the name of India, Burma, Malaya, Australia, British East Africa, British Guiana, Hong Kong, Siam, Singapore, Egypt, Palestine, Canada, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales, as well as Puerto Rico, Guam, the Philippines, Hawaii, Alaska, and the Virgin Islands, hereby declare most emphatically, that this is not an imperialist war.” (p. 398). This quote was the precursor that set off the mentality of the war being a “‘people’s war’ against Fascism.” (p. 398) However, Zinn poses the question that carries the chapter: is it really a people’s war against Fascism? Intervening Zinn note many times in the text that the United States has a history of wedging themselves into other countries’ affairs for their own benefit. An “Open Door Policy in China” enabled the U.S. to have “opportunities equal to other imperial powers in exploiting China” (p. 399) Whereas the Closed Door Policy against Latin America guaranteed the U.S. to be the only one that could meddle in those countries, which they did. According to Zinn, “the United States intervened in Cuba four times, in Nicaragua twice, in Panama six times, in Guatemala once, in Honduras seven times” (p. 399) Specifically with Latin America, the U.S. “engineered a revolution against Colombia and created the ‘independent’ state of Panama in order to build and control the Canal. It sent five thousand marines to Nicaragua in 1926 to counter a revolution, and kept a force there for seven years. It intervened in the Dominican Republic for the fourth time in 1916 and kept troops there for eight years” (p. 399) The U.S. and Japan Before WWII, the U.S. and Japan had established an understanding, as Zinn notes in the text: “So long as Japan remained a well-behaved member of that imperial club of Great Powers who-in keeping with the Open Door Policy- were sharing the exploitation of China, the United States did not object.” (p. 401) However, the U.S.’s paranoia of losing out on their Open Door Policy with China got the best of them. What Was The U.S. Really Fighting For? The U.S. involvement in WWII was mostly fueled by the U.S.’s fear of Japan threat to take over China. That would mean the U.S. would miss out on resources like oil, tin, rubber, scrap iron and other raw materials. Attack on Pearl Harbor Known in history as the “date which would live in infamy”, the attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese actually was a long time coming. Zinn quotes Bruce Russett as saying “Japan's strike against the American naval base climaxed a long series of mutually antagonistic acts. In initiating economic sanctions against Japan the United States undertook actions that were widely recognized in Washington as carrying grave risks of war.” (p. 401) Attack on Hiroshima and Nagasaki As retaliation, the U.S. dropped two atomic bombs on Japanese land; one in Hiroshima--”leaving perhaps 100,000 Japanese dead, and tens of thousands more slowly dying from radiation poisoning” (p. 413)—and another, three days later, over Nagasaki—”with perhaps 50,000 killed” (p. 413). These attacks were justified because they were allegedly intended to end the war quickly without too much damage to civilians—the complete opposite of what they were able to accomplish. Lingering Racism African-Americans in the military were subjected to riding in the lowest part of the ships when traveling overseas. Reminiscent of slave travel. Americans began to hate as well as fear those of Japanese ancestry They became the enemy. Some individuals believed they should be placed in concentration camps. Literature of WWII Some of the literature to emerge during this era are those in a war setting; specifically WWII. These novelizations of the war gave audiences some indication what it was like to be in the war and how it affected a solider. Joseph McCarthy Senator of Wisconsin Very vocal about anti-Communist views Comes into government with antiCommunist agenda Spawns the term “McCarthyism” “the practice of making accusations of disloyalty, especially of pro-Communist activity, in many instances unsupported by proof or based on slight, doubtful, or irrelevant evidence.” (dictionary.com) McCarthyism Zinn sheds light on McCarthyism with this passage from the text: “Speaking to a Women's Republican Club in Wheeling, West Virginia, in early 1950, he held up some papers and shouted: "I have here in my hand a list of 205—a list of names that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping policy in the State Department." The next day, speaking in Salt Lake City, McCarthy claimed he had a list of fifty-seven (the number kept changing) such Communists in the State Department. Shortly afterward, he appeared on the floor of the Senate with photostatic copies of about a hundred dossiers from State Department loyalty files. The dossiers were three years old, and most of the people were no longer with the State Department, but McCarthy read from them anyway, inventing, adding, and changing as he read. In one case, he changed the dossier's description of "liberal" to "communistically inclined," in another form "active fellow traveler" to "active Communist," and so on.” (p. 422) McCarthy’s passionate speeches of anti-Communism begin to spread, instilling in Americans a sense of panic and paranoia. In a sense, Communists became a new target of racism within the United States. The Rosenbergs A couple tried for espionage. Called forward by individuals who’d already been discovered for having communist ties. Zinn argues the couple was framed by “a frequent and highly imaginative liar” named Harry Gold (p. 425) Despite no real hard evidence against them, the Rosenbergs were found guilty. They were sentenced to death by the electric chair. The Rosenberg’s case only added more to the United States’ paranoia over Communism and those working for it undercover. Just Like The Red Scare So much anti-Communism fear was instilled in Americans at this point by McCarthy that it resulted in a mentality similar to the one during the “Red Scare”. On p. 428 of the text, Zinn states that “young and old were taught that aniti-Communism was heroic”. He also goes on to say there were many examples in popular culture that supported this notion Micky Spillane’s book, One Lonely Night, chronicles narrator that has killed many people, all Communists. The superhero of the comic strip Captain America that urged readers to “beware commies, spies, traitors, and foreign agents” (p. 428) Raising Money As a result of all the fear and paranoia, the military budget drastically raised over time. “In 1960, the military budget was $45.8 billion—9.7 percent of the budget.” (p. 428) “By 1970, the U.S. military budget was $80 billion and the corporations involved in military production were making fortunes. Two-thirds of the 40 billion spent on weapons systems was going to twelve or fifteen giant industrial corporations, whose main reason for existence was to fulfill government military contracts.” (p. 429) Work Cited “McCarthyism”. Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. 03 Apr. 2014. <Dictionary.com http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/>. Zinn, Howard. A People’s History of the United States. Harper: New York, 1995. Print.