Black Death PP for Sixth

advertisement

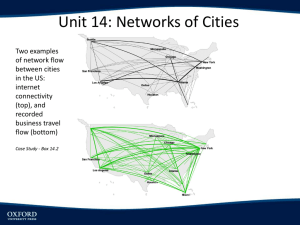

The Black Death Did It Save English? Fig. 1. Dans Macabre In general, most people think it was the bubonic plague, Yersinia Pestis. (A few people think perhaps anthrax, a mutation of cattle murrain, hemorrhagic fever, or some unknown disease.) Fig. 2. Yersinia Pestis Microbes Other Names for the Black Death: The Blue Sickness (the medieval British name for it) Bilbos (The medieval Italian word for it, literally “swellings”) “La Pest” (The medieval French word for it) Pestilencia Magna (The Latin words for “the Great Plague”) Ko-ta-Wen (The Mongolian word for it ) Ta-Wun (The Mandarin Chinese word for it, literally. “Sore-sore”) Ta’un (The Arabic word for it) Today, we call it the black plague or the bubonic plague—but these terms did not appear until hundreds of years later. Fig. 3. Map of plague routes out of China It seems to have come from Central Asia: Mongolian records mentioned it in 1333, 1338, and 1339. Chinese and Indian records mentioned it in 1346. In Europe, it showed up at the Black Sea port of Kaffa in 1347. Fig. 4. Kipchak Khan Janibeg: Mongolian general who besieged the port city of Kaffa Medieval people believed (probably falsely) that Mongols under Kipchak Khan Janibeg catapulted corpses infected with plague into the trading city of Kaffa in the Crimean region. From Kaffa, the plague kept spreading! 1347 1348 1349 Alexandria, Egypt and Messina, Sicily Genoa and Venice in Italy Aberdeen, Scotland and Avignon, France Fig. 5. Map of plague route into Europe taken from “Black Death Pogroms” at http://www.geschichteinchronologie.ch And spreading ! 1349 Paris, France; and Mecca, Arabia 1350 All of the Scandinavian Peninsula; Baghdad in the Mid-East 1351 Kiev, Russia . . . and spreading! Fig. 3. Map of plague routes out of China How is plague spread? Fig. 6. Black rat climbing a chain, from ZooFacts.com Fleas on rats spread it. The disease later could become airborne! Medieval hygiene was often poor, and many people had fleas or lice. Fig. 7: Pullex Irritans, the human flea The European black rats also carried their own species of fleas, and the rats themselves were mostly immune to the deadly plague. Fig. 8: Rattus Rattus, the European Black Rat They were also great swimmers, climbers, and escape artists, which made them hard to quarantine. Infected rat fleas, however, will also bite humans if they can’t feed on rats, and thus humans catch the disease. Once humans are infected, the bacteria can build up in their lungs. They can then cough up microscopic particles of blood, making the disease airborne! Fig. 9: Xenopsylla Cheopis, the rat flea--this pregnant female is heavy with eggs, which are visible as a black spot near her tail Stage I: Fever, trembling, and weakness Stage II: Huge blue or purple “buboes” or swellings in the armpits, throat, and thighs. Stage III: Coughing and peeing blood! Stage IV: Death! Fig. 10: Image of Black Death as a Minstrel Q: How many people died? A: It varied from place to place. Overall, probably one-in-three people died in Europe (perhaps 50-70 million) and maybe 220 million worldwide. The world probably only had 500 million people before the plague outbreak. Some places were hit very hard and others hardly touched. Florence, Italy (90% dead) Sedlec, Czechoslovakia (70% dead) Caux, Normandy (66% dead) Paris, France (42% dead) Genoa, Italy (35% dead) Dublin, Ireland (35% dead) Avignon, France (33% dead) Some 3,000 European villages had “absolute population loss” (which means 100% of the people either died or ran away). The New World (no deaths) Hawaii, Polynesian Islands (no deaths) Galway, Ireland (no deaths ) Lindisfarne, Ireland (no deaths) Western Scotland (no deaths) Pharoese Island (no deaths) Inland Central Africa (no deaths) Sub-Saharan Africa (2% dead) Burgundy, France (4% dead) Amsterdam, Holland (5% dead) Isolated farms, villages, and islands were least likely to suffer a pandemic. So how did such an awful disease help“save” English? To understand that, we have to back up in time, and see how the French language almost became the language of Britain before the plague hit. The image to the right is the first page of Beowulf. It is written in Anglo-Saxon around 800 AD. Anglo-Saxon, or “Old English,” is the ancestor of English today. Fig. 11. (right) The first page of Beowulf. Cotton Vitellius A.x.v. 129 r Edward the Confessor, king of England, died without children to claim his throne. Afterward, three warriors fought to be king. Fig. 12: Bayeux Tapestry depiction of King Edward the Confessor, the last Anglo-Saxon king Each one had a large army, and each one spoke a different language. Fig. 13: Harald Hardraadi the Viking (his army spoke Old Norse) Fig. 14: Harold Godwinson of Wessex (his army spoke Anglo-Saxon) Fig. 15: William the Conqueror (his army spoke Norman French) A Viking conqueror (Harald Hardraadi) A local Anglo-Saxon ruler (Harold Godwinson) A French warlord (Duke William of Normandy) It was a messy fight! Earl Godwinson’s army beat up the Viking one at Stambridge first. When Godwinson’s forces marched south to fight the French invaders. At the start of the fight at Hastings, a lucky French bowman shot Godwinson in the eye and killed him. Godwinson’s Anglo-Saxon army fell apart. Only the Frenchman, William the Conqueror, was left. Between 10661087, he took over of all England and became ruler. Anglo-Saxon became nearly obsolete! Under William’s French rule, all laws and government documents were in French. All the nobles, priests, bishops? They were now French! English became the language of peasants and serfs. Between 1066-1348, no major English writings appeared again until the last half of the 1300s. It looked bad for the English language! So what changed? What was different that let English make a comeback and shook up the French rulers? The Black Plague! The Black Plague severely messed up medieval England. It left a smaller number of workers compared to the number of aristocrats. Yes, some noblemen did die, but not nearly as many nobles died as peasants did. That meant labor become rare. Nobles had to offer incentives like land, money, or legal benefits to keep peasants working. Fig. 16: Holbein Woodcut of Death Serving at Nobleman’s Table It also killed many French priests, bishops, and archbishops in England. Good priests stayed to comfort the dying, and died themselves. Bad priests ran away because they were scared, and they lost their credibility. Because so many Norman French priests died or ran away, the church in England had to open up job positions to English replacements, not just French ones. Priests had to be able to read and write. Now, English speakers—not just Norman French—were increasingly able to do so. Fig. 17: Holbein Woodcut of Bishop being led by Death The next generation of workers suddenly had choices! Don’t like working on the local lord’s farm? Pack up and move! Switch farms! Join a labor guild! Form a chartered town! Become a mercenary! Increasingly, the lower-class English peasants were becoming middle-class. They could demand more money and more education. Gradually, the English language—now blended with French vocabulary—made a comeback!. Fig. 18: Holbein woodcut of Death trying to stop a soldier from leaving English made a comeback! The language that develops next is called “Middle English.” It’s a lot closer to our language—but it’s spelled differently and pronounced differently. Middle English That love laste wel a fourtenyght, For it no lengere mihte laste, So nyh my lif was ate laste. Bot now, allas, to late war That I ne hadde him loved ar: For Deth cam so in haste bime, Er I therto hadde eny time, That it ne mihte ben achieved. --John Gower, Confessio Amantis, Book IV Modern English That love lasted only a fortnight, But it might no longer last Because my life was ebbing fast. But now, sadly, too late I learned That I had not loved this lad earlier. For Death came himself so quickly That there was no time, That our love might not be achieved. --John Gower, Confessio Amantis, Book IV Geoffrey Chaucer: Finally, by the 1380s, Chaucer chose to write in English rather than French! Most British writers before 1348 choose to use Latin or French, like John Gower. Chaucer also did his early writings in French, but he switched to English in The Book of the Duchess, Troilus and Criseyde, and The Canterbury Tales. Chaucer had been eight years old when the Black Plague hit England. Those who survived the generation of death lived in a world with more land, more wealth, more rights, and more English. Fig. 19: Geoffrey Chaucer, adapted from the Hoccleve Portrait However, traces of the Black Plague may still persist in some creepy phrases today, ranging from Shakespeare to children’s rhymes! Ring around the rosies, A pocketful of posies, Ashes, ashes, We all fall down. --children’s rhyme (first recorded in 19th century, but may date back to the 1400s) “A plague a’ both your houses!” --Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, Act I, Scene 3, line 91 Finis! That’s How the Black Death Saved English! Fig. 1. Hans Holbein. Dans Macabre. 15th-Century Woodcut. Lyons, 1538. Fig. 2. Yersinia Pestis. Taken from “Black Death Pogroms” <http://www.geschichteinchronologie.ch/MA/judentum EncJud_pest-black-death-pogroms-1348-1350-ENGL.html>. 14 May 2012. Web. Fig. 3. Adapted from Geoffrey Mars’ The Medieval Plague: The Black Death and the Middle Ages. New York: Doubleday, 1971. 1. Fig. 4. Kipchak Khan Janibeg. Beijing. 16th-Century Scroll Painting. Fig. 5. Map of Plague route into Europe taken from “Black Death Pogroms” at <http://www.geschichteinchronologie.ch >. 14 May 2012. Web. Figs. 6-9. All animal images taken from ZooFacts.com. 14 May 2012. Web. Fig. 10. Anonymous. Death as Minstrel. N.p. N.d.. Fig. 11. First page of Beowulf. Cotton Vitellius MS A.x.v. 129 r. As reproduced in Julius Zupitza's Beowulf: Autotypes of the Unique Cotton MS Vitellius A.xv. in the British Museum with a Transliteration and Notes. E.E.T.S. O.S. 77. London: Trubner & Co., 1882. Figs. 12-15 Foys, Martin K. Bayeux Tapestry Digital Edition. Individual license ed; CD-ROM, 2003. Figs. 16-18 Hans Holbein. Alphabet of Death. 15th-Century Woodcut. Lyons, 1538. Fig. 19 Geoffrey Chaucer. Adapted from the Thomas Hoccleve Portrait. Early 15th century. All other images free clipart from clipart.com. --gratias tibi!