A Firm League of Friendship - Northern Illinois University

advertisement

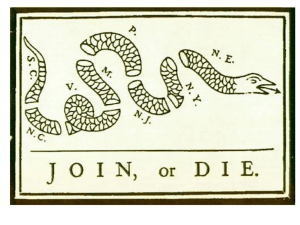

A Firm League of Friendship: The Articles of Confederation Artemus Ward Dept. of Political Science Northern Illinois University aeward@niu.edu http://www.niu.edu/polisci/faculty/profiles/ward/ Introduction • The colonies finally agreed to act collectively in the face of British government decisions that threatened their livelihood. • The structure of the Continental and Confederation Congress under the Articles of Confederation allowed individual states to preserve their autonomy, which was particularly important for southern states that sought to preserve slavery. • The “ineffectiveness” of the Articles can be viewed as the logical, by design, outcome of states’ rights, anti-federalists who had little use for collective action beyond matters of foreign war and peace. Collective Action • Since at least 1754, Benjamin Franklin had been urging the colonies to act in concert to collectively solve local problems. • Two decades later, representatives from the 13 American colonies comprised a Continental Congress and began meeting in 1774. • Two years later they declared independence from England. • The Declaration made plain that the 13 states were “united” in declaring independence and pledging to fight together. • This unanimity, however, said little about the general legal authority of the Continental Congress in any future situation in which the newly independent states might seek to disagree among themselves, or where one or more states might seek to leave the alliance after independence had been won. • In short, the Declaration only committed the 13 states to independence and nothing more. Declaration of Independence 13 Sovereign States • The opening passages of the Articles of Confederation variously described the arrangement among the states as a “confederacy,” “confederation,” or “firm league of friendship with each other.” • Article II: ”Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated.” • Article III: “The said States hereby severally enter into a firm league of friendship with each other, for their common defense, the security of their liberties, and their mutual and general welfare, binding themselves to assist each other, against all force offered to, or attacks made upon them, or any of them, on account of religion, sovereignty, trade, or any other pretense whatever." • Legally, the words “confederacy,” “confederation,” and “league” all connoted the same thing: The “United States” would be an alliance, a multilateral treaty of sovereign nation-states. • Moreover, the word “retains” strongly suggested that each state was already sovereign and had been so since independence. • Each state chose and sent their own delegates (up to 7), set their pay, told them how to vote, and could recall them at will. • Each state had one vote, 9 votes were required to pass legislation, and unanimity was required to amend the Articles. Articles: Key Provisions • Article IV: established equal treatment and freedom of movement for inhabitants of each state except for “paupers, vagabonds, and fugitives from justice.” It also provided for extradition from criminal matters. • Article VI: empowered congress to conduct foreign affairs (political and commercial) and to declare war. It prohibited states from foreign affairs, war, and from maintaining standing armies (but required they have ready militias). • Article VIII: stipulated that congressional expenditures would be paid by funds raised by state legislatures and apportioned based on real property values of the states. • Article IX: empowered congress to declare war, enter into treaties, raise armies and navies, resolve disputes between states, coin money, establish a post office, and conduct Indian affairs. Congress of the Confederation (1781-1789) • Congress was initially effective at guiding the states through the final stages of the revolutionary war. It set up committees on war, foreign affairs, and finance. • Once the war ended, it quickly declined in importance and the turnover rate for delegates was high as work in state government was preferred by those who might serve. • Yet there were 2 important acts that Congress passed during peacetime: 1. Land Ordinance (1785) and Northwest Ordinance (1787) – established federal control of the Northwest Territory (land west of Pennsylvania and north of the Ohio river) with the understanding that new states would be created—all of them without slavery. Ultimately, the land was divided among Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota. 2. Philadelphia Convention (1787) – all states agreed to a convention to amend the Articles. Articles: A Lack of Means • Although on paper Congress under the Articles enjoyed some important powers, it had no effective means of carrying them out. – It could not directly tax individuals or legislate upon them; – It had no explicit “legislative” or “governmental” power to make binding “law” enforceable in state courts; – It lacked broad authority to set up its own general courts; – It could not regulate foreign or interstate commerce; – and it could raise troops and money only by “requisitioning” contributions from each state. On paper, such requisitions were “binding.” In practice, they were mere requests. It was said, Congress “may declare every thing, but do nothing.” Ineffectiveness • Congress could not draft and pay soldiers and instead had to ask the states to send troops and pay them. • Congress promised revolutionary war soldiers a pension but the states refused to pay when the war ended. • When Congress tried to print its own money it quickly depreciated and became worthless. • The Treaty of Paris (1783) which formally ended the war, languished for months as state delegates failed to attend congressional sessions. • The states failed to fund a naval campaign to defend American interests against Barbary pirates on the high seas. Fatal Omission • By 1787, the Confederation was in shambles. • Various states failed to honor requisitions, enacted laws violating duly ratified treaties, waged unauthorized local wars against Indian tribes, and maintained standing armies without congressional permission—all in plain contravention of the Articles. • As James Madison noted, the “fatal omission” of the Articles was its failure to give Congress any power of “coercion” over the states. He said this arose naturally “from a mistaken confidence that the justice, the good faith, the honor, the sound policy” of the assemblies reflected both their own “enthusiastic virtue” and their “inexperience of the crisis” the war brought. In short, the heady patriotism of revolution led to the naïve notion that state legislators and their constituents would nobly comply with the wishes of Congress. Why Scrap the Articles? • Of course the initial charge of the delegates to the 1787 Philadelphia convention was to amend the Articles. But they quickly knew that was going to be impossible. • Why? Because the closing passage (Article XIII) of that document required that any amendment would have to be agreed to by all 13 state legislatures. • Every time the Confederation Congress had previously proposed amendments, one or more states had said no. Even Rhode Island refused to send delegates to Philadelphia. • Thus, the new Constitution would go into effect after only 9 of the 13 states agreed and it could be amended by ¾ of the states. Conclusion • The colonies only agreed to act collectively because each felt their livelihoods was under threat from Britain. • After the war, Congress was ineffective and weak under the Articles of Confederation—which was arguably by design. • Because the Articles were essentially impossible to amend, the Philadelphia delegates (all reformers) had little choice but to create a new collective agreement.