Roots of the Modern University - Center for 21st Century Universities

advertisement

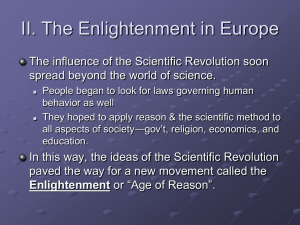

1 ROOTS OF THE MODERN UNIVERSITY Conditions Leading to the Emergence of Universities in the West Tentative Discussion Outline 2 Modern University Rankings Early Concepts for Universities Universities in the Late Middle Ages Medieval / Pre-Midieval University Precursors Forces Leading to Emergence of University Systems The Development and Convergence of: Society, Culture, Warfare and Demographics Information and Communications Technologies The Key Role of Government and Geography Characteristics of the Emergent University: Concepts for Authority, Organization and Governance State / Institutional Funding Study and Research Disciplinar[ity] Roots of the Modern University Useful Additional Reading 3 Hailman, W. N. (1874). Twelve lectures on the history of pedagogy: Delivered before the Cincinnati Teachers' Association. New York: Van Antwerp, Bragg and Co. Makdisi, G. (1989). Scholasticism and Humanism in Classical Islam and the Christian West. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 109 (2), 175-182. Marginson, S. (2007). Global university rankings: where to from here? Asia-Pacific Association for International Education. Singapore: National University of Singapore. University 4 Per the World Encyclopedia. Philip's, 2005. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. “university”: Institution of higher learning. From the latin "universitas": a corporation of students. Universities grew from the studia generalia of the 12th century, which provided education for priests and monks and were attended by students from all parts of Europe. In the 11th century, Bologna became an important centre of legal studies. Other great studia generalia were founded in the mid-12th century at Paris, Oxford, and Cambridge. Given this, universities would be a medieval European phenomenon with the oldest university being the University of Magnaura in Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey), founded in 849 by the regent Bardas of emperor Michael III. All of those listed survive in some form to this day. Comparison of University Rating Criteria 5 Cited in Marginson, 2007, pg 6, 7. ARWU ‘Top 100’ Ratings 6 116 Total Universities achieved ‘Top 100’ ratings Since 2003 Austria – high rank: 84 Belgium (-1) – high rank: 90 Canada (3 Univs) – high rank: 90 Denmark (-1) – high rank: 97 Australia (3(-1) Univs) – high rank: 49 France (4(-1) Univs) – high rank: 39 Germany (8(-2) Univs) – high rank: 45 Israel – high rank: 60 Italy (-1) – high rank: 70 Japan (6(-1) Univs) – high rank: 14 Netherlands (2(-1) Univs) – high rank: 39 Norway – high rank: 63 Russia – high rank: 66 Sweden (4 Univs) – high rank: 39 Switzerland (2 Univs) – high rank: 45 UK (10 Univs) – high rank: 2 US (67(-8) Univs) – high rank: 1 Bold / Italics indicates achievement of ranking 15 or better in at least one report. (-X) indicates number of non-perennial ‘Top 100’ universities achieving a ‘Top 100’ ranking 3 or less times in 8 years.. NOTE: This is not an endorsement of ARWU Rating Standards. These data were selected because they are a non-western source of authoritative University rankings. A Sampling of THES 2010 Rankings 7 Early Universities 8 University of Bologna (1088) •Chartered by Frederick I Barbarossa in 1158 •Notable for teaching of canon and civil law. •The only degree granted (until modern times) was the doctorate. •Alma mater for: Dante, Petrarch and Oxford University (~1096/1167) •Oldest university in the English-speaking world •Rapid growth when Henry II banned English students from Univ of Paris. (1167) •Masters were recognized as a universitas in 1231. •Set back by Anglican break with Catholic Church and the Reformation. Copernicus University of Paris (1231) •The first clearly established university through Papal Bull. •Intended to resolve tensions between ‘church’ students and local governors. •Played an important part in the function of the Church, during the Great Schism – and political power use until the French Revolution. Charles University (1347) •The first university in Central Europe opened in 1349. •Modeled on Univ of Paris – Established by Papal Bull. •Provided privileges and immunities from the secular authorities. •Alma mater for: Tesla, Albert I, Einstein Medieval Universities 14 Even Earlier Institutions 15 Nalanda, India, (~5th Century B.C.) al-Qarawīyīn University, Morocco - 859 Platonic Academy, Athens, 387B.C.) What Changes Led to Universities as an Innovation? 21 Demography Culture Religion (& Philosophy) Politics War Economy ? Science / Technology Black Death 23 The Renaissance 27 A cultural movement that spanned roughly the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Florence in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe. Included a resurgence of learning based on classical sources. Its influence affected literature, philosophy, art, politics, science, religion, and other aspects of intellectual inquiry. Renaissance scholars employed the humanist method in study, and searched for realism and human emotion in art. Humanism 28 A method of learning - humanists would study ancient texts in the original, and appraise them through a combination of reasoning and empirical evidence. Based on the of the five humanities: poetry, grammar, history, moral philosophy and rhetoric. Product of the Early Renaissance Jagiellonian University (1364) 29 Religion (& Philosophy) 30 The Rise of Christianity in Europe Constantine - Edict of Milan in (313) / Council of Nicea (325). Charlemagne – (800) Central and Western Europe ‘re’united under Rome as an Empire. The Christian religion received imperial sanction. His rule is also associated with the Carolingian Renaissance, a revival of art, religion, and culture through the medium of the Catholic Church. Later Religious Transitions The Inquisition (12th through 16th Centuries). The Reformation (1517 – 1648) The Reformation 34 Puritan migration (1620 -1640) 35 Politics and War 36 Edict of Milan (Constatine, 313) The Role of the Papacy (Charlemagne, 800) Magna Carta (John I, 1215) Key Wars in Europe: Barbarian invasions (Huns - 370 to 400) 100 Years War (1337-1453) 30 Years War (1618–1648) All Leading Toward the ‘Age of Enlightenment’ Wars in Europe 38 ~600-793 Frisian-Frankish Wars 1208-1227 Conquest of Estonia 1209-1229 Albigensian Crusade 1220-1264 The Age of the Sturlungs 1282-1302 War of the Sicilian Vespers 1296-1357 Wars of Scottish Independence 1337-1453 Hundred Years' War 1419-1434 Hussite Wars 1455-1487 Wars of the Roses 1499 Swabian War 1522–1559 Habsburg-Valois Wars 1558-1583 Livonian War 1562-1598 French Wars of Religion 1568–1648 Eighty Years' War 1580-1583 War of the Portuguese Succession 1585-1604 Anglo-Spanish War (1585) 1594-1603 Nine Years War (Ireland) 1618–1648 Thirty Years' War 1640-1688 Portuguese Restoration War 1642–1651 English Civil War 1652-1674 Anglo-Dutch Wars 1667–1668 War of Devolution 1667–1683 Great Turkish War 1672-1678 Franco-Dutch War 1688-1697 War of the League of Augsburg 1700–1721 Great Northern War 1701–1713 War of the Spanish Succession 1718-1720 War of the Quadruple Alliance 1740–1748 War of the Austrian Succession 1756–1763 Seven Years' War 1789–1799 French Revolution 100 Years War (1337 to 1463) 39 New technologies empowered soldiery at the expense of lords and noble knights – gave rise to mercenary/bandit armies. France’s population reduced by two-thirds due to the invasion, civil wars, deadly epidemics, famines and marauding mercenary armies. Ended with England’s isolation as an Island nation. Also resulted in the emergence of standing armies in England and France along with concepts for ‘nationalism.’ 30 Years War 40 The last major religious war in mainland Europereligious bloodshed accompanying the Reformation, in 1648. Initially fought between Protestants and Catholics in the Holy Roman Empire. German states reduced by about 15% to 30% and caused serious dislocations to both the economies and populations of central Europe Formally ended by the Peace of Westphalia: Established the basic tenets of the sovereign nation-state. Provided that the citizenry of a respective nation were subjected first and foremost to the laws and whims of their own respective government rather than to those of neighboring powers, be they religious or secular. Science and Technology 42 High Middle Ages - Technology 43 Inventions , innovations and European Acquisitions of 12th/13th century: Windmills Watermills Printing (though not yet with movable type) Gunpowder Spectacles Scissors Mechanical Clocks Improved ships Paper Spinning Wheel Magnetic Compass Arabic Numeral Ship Stern-mounted Rudders Fibonnacci and Modern Numerology 44 Nine Indian figures are: 987654321 With these nine figures, and with the sign 0 ... any number may be written. Consider the Changes to the Speed of Transmission and Thought? 45 1202 • 1440 186,282 MCCII • MCDXL CLXXXVICCXXCII Mσβ ʹ • Mυμ ʹ ιη M,ϛτπβʹ To represent numbers from 1,000 to 999,999 the same letters are reused to serve as thousands, tens of thousands, and hundreds of thousands. A "left keraia" (Unicode U+0375, ‘Greek Lower Numeral Sign’) is put in front of thousands to distinguish them from the standard use. For example, 2010 is represented as ͵βιʹ (2000 + 10). 48 To represent greater numbers, the Greeks also used the myriad from the old Attic numeral system in their notation. Its value is 10,000; the number of myriads was written above its symbol (Mʹ). For example (keraias replaced for technical reasons): History of Paper 50 Gutenburg’s Press circa 1439 51 British Agricultural Revolution 52 A period of development in Britain between the 17th century and the end of the 19th century. Four Key Innovations: Seed Drill Iron plough Three-field Crop Rotation Selective breeding Supported unprecedented population growth, freeing up a significant percentage of the workforce, and thereby helped drive the Industrial Revolution. Possible Issues to Consider 53 What is a college?: An interrelated system of ideas (Birnbaum, R. (1991), preface). Are they organizations, systems or inventions? How do they reflect characteristics of all? (Birnbaum, 1). Organizational Aspects (Birnbaum, 3). : Birnbaum’s “apparent paradox”: Does the success of universities occur because of or despite the inherent detractors? Early concepts of “Governance” . . . among the largest industries in the nation . . .least business like and well managed exhibit unparalleled diversity, access and quality . . . poorly run but highly effective Birnbaum (pp 4-5) reflects that fundamental authority lies with the state, is but is established within the institution – from there shared among “trustees, presidents, and faculty.” How much power should each have? Division of power between administrators and faculty (Highlighted in Birnbaum, R.(1991): How Colleges Work) The Emerging Epicenter of Learning Potential 54 Questions for the Future 55 What does the increasing automation of mathematical manipulation portend for mathematical intuition and creative insight (i.e Fibonnacci numbers) How might the gradual dissipation of civil authority via globalization affect sponsorship and governance over universities, and what if this gradual trend dramatically reverses itself? What were the further effects of later global scourges on the development of higher education? How does the lack of any university tradition in Africa confirm or refute any of the lessons from history? What are the potential long term effects of global and national rankings? How does the increasing accessibility of selected free knowledge (via Wikipedia and Gutenburg project as examples) suggest about the relative influence of protected expert knowledge and the role universities play in developing and protecting these? 56 Back Up Slides and Miscellanea QUESTIONS FOR EACH TOPIC 57 What changes happened in this period and what drove these changes? What was happening more broadly in society during this period? How was access to university education allocated? How should it be now? When did research get added to the mission of the university? How was research funded and evaluated? When did service get added to the mission of the university? How was service funded and evaluated? How have changes in student demographics (race, gender, age, etc.) affected the roles and behavior of universities? Where did academia’s financial resources come from; how were they expended? What was the typical business model of a university of this period? How were teachers educated, selected and paid? How were universities, programs and teachers evaluated? When and why did tenure emerge and how has it changed? When did endowments and gifts start to play a major role? When and why did the notion of tuition and fees emerge? What are the basic elements of learning in higher education (e.g., reading, labs, lectures, projects, etc.) and how are they assessed? Who was educated, how did they pay for it, and did it cover all costs? How did the idea of courses, semesters, etc. emerge? What are the roles of disciplines, departments, and schools in academia? How do new disciplines, departments, and schools come into existence? How are they eliminated? When and why did the constructs of majors and minors emerge? How did the degree structure (BS, MS, PhD) come about? What aspects of student development do universities support in addition to education and training? When and why did rankings of universities and programs emerge? When and why did sports become important and expensive? What has been academia’s relationship with industry and government? What has been the public’s attitude towards higher education? What are the current roles of the various stakeholders (students, faculty, administrators, trustees, legislators, research funders, student employers, etc.) in shaping the structure and function of the university? How will American universities be affected by the rise of new universities in the developing world, especially India and China? Authority and Governance 60 Universities are generally established by statute or charter. In the United Kingdom, for instance, a university is instituted by Act of Parliament or Royal Charter; in either case generally with the approval of Privy Council, and only such recognized bodies can award degrees of any kind. http://www.cwrl.utexas.edu/~bump/OriginUniversities.html Similarly to the other early medieval universities (Bologna, Padua, Cambridge, Oxford), the University of Paris was already well established before it received a specific foundation act from the Church in 1200.[4] "[T]he papal bull of 1233, which stipulated that anyone admitted to be a teacher in Toulouse had the right to teach everywhere without further examinations (ius ubique docendi), Under the governance of the Church, students wore robes and shaved the tops of their heads in tonsure, to signify they were under the protection of the church. Students operated according to the rules and laws of the Church and were not subject to the king's laws or courts. Two things were necessary to be a professor: knowledge and appointment. Knowledge was proved by examination, the appointment came from the examiner himself, who was the head of the school, and was known as scholasticus, capiscol, and chancellor. This was called the licence or faculty to teach. The licence had to be granted freely. No one could teach without it; on the other hand, the examiner could not refuse to award it when the applicant deserved it. In Paris - The Rector The university was organized as follows: at the head of the teaching body was a rector. The office was elective and of short duration; at first it was limited to four or six weeks. Simon de Brion, legate of the Holy See in France, realizing that such frequent changes caused serious inconvenience, decided that the rectorate should last three months, and this rule was observed for three years. Then the term was lengthened to one, two, and sometimes three years. The right of election belonged to the procurators of the four nations Faculties To classify professors' knowledge, the schools of Paris gradually divided into faculties. Professors of the same science were brought into closer contact until the community of rights and interests cemented the union and made them distinct groups. The faculty of medicine seems to have been the last to form. But the four faculties were already formally established by 1254, when the university described in a letter "theology, jurisprudence, medicine, and rational, natural, and moral philosophy". The masters of theology often set the example for the other faculties, e.g. they were the first to adopt an official seal. The faculties of theology, canon law, and medicine, were called "superior faculties". The title of "Dean" as designating the head of a faculty, came into use by 1268 in the faculties of law and medicine, and by 1296 in the faculty of theology. It seems that at first the deans were the oldest masters. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_of_Paris Pre-Modern College Governance Structures 61 Trustees were clergymen Administration and faculty: a president and a handful of tutors Boards – fully in charge Increased complexity led to emergence of presidents (Birnbaum, 5) French Academies 66 The history of Academies in France during the Enlightenment begins with the Academy of Science, founded in 1666 in Paris. From the beginning, the Academy was closely tied to the French state, acting as an extension of a government seriously lacking in scientists. Beyond serving the monarchy, the Academy had two primary purposes: it helped promote and organize new disciplines, and it trained new scientists. It also contributed to the enhancement of scientists’ social status, considered them to be the “most useful of all citizens". Academies demonstrate the rising interest in science along with its increasing secularization, as evidenced by the small number of clerics who were members (13 percent).[17] The presence of the French academies in the public sphere cannot be attributed to their membership; although the majority of their members were bourgeois, the exclusive institution was only open to elite Parisian scholars. They did perceive themselves to be “interpreters of the sciences for the people”. Indeed, it was with this in mind that academians took it upon themselves to disprove the popular pseudo-science of mesmerism.[18] However, the strongest case for the French Academies being part of the public sphere comes the concours académiques (roughly translated as academic contests) they sponsored throughout France. As Jeremy L. Caradonna argues in a recent article in the Annales, “Prendre part au siècle des Lumières: Le concours académique et la culture intellectuelle au XVIIIe siècle”, these academic contests were perhaps the most public of any institution during the Enlightenment. L’Académie française revived a practice dating back to the Middle Ages when it revived public contests in the mid-17th century. The subject manner was generally religious and/or monarchical, and featured essays, poetry, and painting. By roughly 1725, however, this subject matter had radically expanded and diversified, including “royal propaganda, philosophical battles, and critical ruminations on the social and political institutions of the Old Regime.” Controversial topics were not always avoided: Caradonna cites as examples the theories of Newton and Descartes, the slave trade, women's education, and justice in France.[19] More importantly, the contests were open to all, and the enforced anonymity of each submission guaranteed that neither gender nor social rank would determine the judging. Indeed, although the “vast majority” of participants belonged to the wealthier strata of society (“the liberal arts, the clergy, the judiciary, and the medical profession”), there were some cases of the popular classes submitting essays, and even winning. [20] Similarly, a significant number of women participated –and won – the competitions. Of a total of 2 300 prize competitions offered in France, women won 49 – perhaps a small number by modern standards, but very significant in an age in which most women did not have any academic training. Indeed, the majority of the winning entries were for poetry competitions, a genre commonly stressed in women’s education. [21] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Age_of_Enlightenment#Academies The High Middle Ages - Religion 67 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High_Middle_Ages Golden age of monasticism The late 11th century/early-mid 12th century was the height of the golden age of Christian monasticism (8th-12th centuries). Benedictine Order - black robed monks Cistercian Order - white robed monks Mendicant orders The 13th century saw the rise of the Mendicant orders such as the: Bernard of Clairvaux Franciscans (Friars Minor, commonly known as the Grey Friars), founded 1209 Carmelites (Hermits of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Carmel, commonly known as the White Friars), founded 1206–1214 Dominicans (Order of Preachers, commonly called the Black Friars), founded 1215 Augustinians (Hermits of St. Augustine, commonly called the austin Friars), founded 1256 Philosophical and scientific teaching of the Early Middle Ages was based upon few copies and commentaries of ancient Greek texts that remained in Western Europe after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. Most of them were studied only in the Latin as knowledge of Greek was very limited. This scenario changed during the Renaissance of the 12th century. The intellectual revitalization of Europe started with the birth of medieval universities. 68 Carolingian Renaissance http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carolingi an_Renaissance the history of ideas the Carolingian Renaissance stands out as a period of intellectual and cultural revival occurring from the late eighth century, in the generation of Alcuin, to the 9th century, and the generation of Heiric of Auxerre, with the peak of the activities coordinated during the reigns of the Carolingian rulers Charlemagne and Louis the Pious.[1] During this period there was an increase of literature, writing, the arts, architecture, jurisprudence, liturgical reforms and scriptural studies. Charlemagne's Admonitio generalis (789) and his Epistola de litteris colendis served as manifestos. The effects of this cultural revival, however, were largely limited to a small group of court literati: "it had a spectacular effect on education and culture in Francia, a debatable effect on artistic endeavors, and an unmeasurable effect on what mattered most to the Carolingians, the moral regeneration of society," John Contreni observes.[2 The Enlightenment 69 The "Enlightenment" was not a single movement or school of thought, for these philosophies were often mutually contradictory or divergent. The Enlightenment was less a set of ideas than it was a set of values. At its core was a critical questioning of traditional institutions, customs, and morals, and a strong belief in rationality and science. Thus, there was still a considerable degree of similarity between competing philosophies.[2] Some historians also include the late 17th century, which is typically known as the Age of Reason or Age of Rationalism, as part of the Enlightenment; however, most historians consider the Age of Reason to be a prelude to the ideas of the Enlightenment.[3] Modernity, by contrast, is used to refer to the period after The Enlightenment; albeit generally emphasizing social conditions rather than specific philosophies There is little consensus on when to date the start of the age of Enlightenment and some scholars simply use the beginning of the 18th century or the middle of the 18th century as a default date.[6] If taken back to the mid-17th century, the Enlightenment would trace its origins to Descartes' Discourse on the Method, published in 1637. Others define the Enlightenment as beginning in Britain's Glorious Revolution of 1688 or with the publication of Isaac Newton's Principia Mathematica which first appeared in 1687. As to its end, some scholars use the French Revolution of 1789 or the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars (1804–15) as a convenient point in time with which to date the end of the Enlightenment.[7] Influence Historian Peter Gay asserts the Enlightenment broke through "the sacred circle,"[8] whose dogma had circumscribed thinking. The Sacred Circle is a term used by Peter Gay to describe the interdependent relationship between the hereditary aristocracy, the leaders of the church and the text of the Bible. This interrelationship manifests itself as kings invoking the doctrine "Divine Right of Kings" to rule. Thus church sanctioned the rule of the king and the king defended the church in return. The Enlightenment is held to be the source of critical ideas, such as the centrality of freedom, democracy, and reason as primary values of society. This view argues that the establishment of a contractual basis of rights would lead to the market mechanism and capitalism, the scientific method, religious tolerance, and the organization of states into self-governing republics through democratic means. In this view, the tendency of the philosophes in particular to apply rationality to every problem is considered the essential change. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Age_of_Enlightenment Rationality and the Enlightenment 70 Rationality is the traditional leitmotif of the Enlightenment They quote approvingly the Edinburgh chemist Joseph Black’s condemnation of ‘those men who, shut up in their Closets in study and retirement, have obtained the appellation of Learned Philosophers, they in general puzzle more than they illustrate, they are wrapt in a veil of Systems and of Theories and seldom make improvements or discoveries of Use to Mankind’ (p. 117). Jacob and Stewart follow Black in favouring what he called ‘rustic’ philosophers, the inventors who bettered themselves and their surroundings, such as farmers who improved their ploughs or analysed soil composition. The High Middle Ages - Culture 71 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High_Middle_Ages The High Middle Ages produced many different forms of intellectual, spiritual and artistic works. This age saw the rise of modern nation-states in Western Europe and the ascent of the great Italian city-states. The rediscovery of the works of Aristotle led Thomas Aquinas and other thinkers to develop the philosophy of Scholasticism. In architecture, many of the most notable Gothic cathedrals were built or completed during this era. Golden age of monasticism The late 11th century/early-mid 12th century was the height of the golden age of Christian monasticism (8th-12th centuries). Benedictine Order - black robed monks Cistercian Order - white robed monks Bernard of Clairvaux Mendicant orders The 13th century saw the rise of the Mendicant orders such as the: Franciscans (Friars Minor, commonly known as the Grey Friars), founded 1209 Carmelites (Hermits of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Carmel, commonly known as the White Friars), founded 1206–1214 Dominicans (Order of Preachers, commonly called the Black Friars), founded 1215 Augustinians (Hermits of St. Augustine, commonly called the austin Friars), founded 1256 Philosophical and scientific teaching of the Early Middle Ages was based upon few copies and commentaries of ancient Greek texts that remained in Western Europe after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. Most of them were studied only in the Latin as knowledge of Greek was very limited. This scenario changed during the Renaissance of the 12th century. The intellectual revitalization of Europe started with the birth of medieval universities. Puritan migration 72 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Migration_to_New_England_(1620%E2%80%931640) The Puritan migration to New England was very marked in its effects in the two decades from 1620 to 1640, after which it declined sharply for a while. The term Great Migration usually refers to the migration in this period of English settlers, primarily Puritans to Massachusetts and the warm islands of the West Indies, especially the sugar rich island of Barbados, 1630-40. They came in family groups, rather than as isolated individuals and were motivated chiefly by a quest for freedom to practice their Puritan religion.[1] From 1630 through 1640 approximately 20,000 colonists came to New England.[3] The so-called Great Migration is not so named because of sheer numbers, which were much less than the number of English citizens who emigrated to Ireland and the Caribbean during this time. The distinction drawn is that the movement of colonists to New England was not predominantly male, but of families with some education, leading relatively prosperous lives.[1] Winthrop's noted words, a City upon a Hill, refer to a vision of a new society, not just economic opportunity. Moore (2007) estimates that 7 to 11 percent of colonists returned to England after 1640, including about a third of the clergymen.[4] The Puritans created a deeply religious, socially tight-knit, and politically innovative culture that is still present in the modern United States. They hoped this new land would serve as a "redeemer nation." They fled England and in America attempted to create a "nation of saints": an intensely religious, thoroughly righteous community designed to be an example for all of Europe. Roger Williams, who preached religious toleration, separation of Church and State, and a complete break with the Church of England, was banished and founded Rhode Island Colony, which became a haven for other refugees from the Puritan community, such as Anne Hutchinson.[5] Quakers were brutally expelled from Massachusetts, but they were welcomed in Rhode Island.[6] Bacon, Locke and Francke 73 Bacon had led the way to inductive investigation with reference to external nature; Locke applied the same principles to the study of the internal—of the mental nature of man—and laid down the results of his labors in his " E^say on Human Understanding." Thus he became the founder of empirical psychology, so important in modern pedagogy. More particularly, he established the important doctrine that there are no innate principles in the mind, and that all ideas come from sensation or reflection, from external or internal experience or observation. Indeed, Locke's " Thoughts on Education" have throughout special reference to the training of young noblemen, since his position, as tutor in a noble family, gave rise to the treatise. While they, therefore, contain many valuable thoughts, they do not contain any thing about the arrangement of public institutions, education of girls, etc., and have no claim as a system of universal education. Formalism and scholasticism continued to rule the schools where they existed. the pietists made war upon the dogmatism of an established church and upon the aristocratic isolation of the schools, and struggled for active and general diffusion of practical Christianity and for the popularizing of education. [Speaking of Francke] In 1691, the university of Halle was founded, and, through Spener's influence, Pranclie was appointed professor of Greek and Oriental languages in the new university, and, at the same time, pastor of the suburb Glaucha. Hailman, 63, 67-78 Academies 74 Academies The history of Academies in France during the Enlightenment begins with the Academy of Science, founded in 1666 in Paris. From the beginning, the Academy was closely tied to the French state, acting as an extension of a government seriously lacking in scientists. Beyond serving the monarchy, the Academy had two primary purposes: it helped promote and organize new disciplines, and it trained new scientists. It also contributed to the enhancement of scientists’ social status, considered them to be the “most useful of all citizens". Academies demonstrate the rising interest in science along with its increasing secularization, as evidenced by the small number of clerics who were members (13 percent).[18] The presence of the French academies in the public sphere cannot be attributed to their membership; although the majority of their members were bourgeois, the exclusive institution was only open to elite Parisian scholars. They did perceive themselves to be “interpreters of the sciences for the people”. Indeed, it was with this in mind that academians took it upon themselves to disprove the popular pseudo-science of mesmerism.[19] However, the strongest case for the French Academies being part of the public sphere comes the concours académiques (roughly translated as academic contests) they sponsored throughout France. As Jeremy L. Caradonna argues in a recent article in the Annales, “Prendre part au siècle des Lumières: Le concours académique et la culture intellectuelle au XVIIIe siècle”, these academic contests were perhaps the most public of any institution during the Enlightenment. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Age_of_Enlightenment Universities in the Americas 75 The first university outside of Europe in that tradition was the Real y Pontificia Universidad de México, today the National University of Mexico (UNAM) founded in 1551 by the Spanish Crown in the Viceroyalty of the New Spain, and inspired by the University of Salamanca. http://www.cwrl.utexas.edu/~bump/OriginUniversit ies.html Universities in America 76 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universit%C3%A9_Laval Laval University (French: Université Laval) is the oldest centre of education in Canada and was the first institution in North America to offer higher education in French. Its main campus is located in Quebec City, Quebec, the capital of the province, on the outskirts of the historic city. The origins of the university are the Séminaire de Québec founded in 1663 by François de Laval, the first bishop of New France. The Séminaire de Québec was granted a Royal Charter on December 8, 1852, by Queen Victoria, creating Université Laval with 'the rights and privileges of a university‘ The governance structure at Laval incorporates the powers of board and senate. The governance was modelled on the provincial University of Toronto Act of 1906 which established a bicameral system of university government consisting of a senate (faculty), responsible for academic policy, and a board of governors (citizens) exercising exclusive control over financial policy and having formal authority in all other matters. The president, appointed by the board, was to provide a link between the 2 bodies and to perform institutional leadership. [3] In 1911, the Medical Faculty of Université Laval set up courses on public hygiene. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harvard_University#Colonial Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States[6] and the first corporation (officially The President and Fellows of Harvard College) chartered in the country. Harvard's history, influence, and wealth have made it one of the most prestigious universities in the world.[7][8] Although it was never formally affiliated with a church, the college primarily trained Congregationalist and Unitarian clergy. Harvard's curriculum and students became increasingly secular throughout the eighteenth century and by the nineteenth century had emerged as the central cultural establishment among Boston elites.[9][10] The charter creating the corporation of Harvard College came in 1650. In the early years, the College trained many Puritan ministers.[17] The college offered a classic academic course based on the English university model—many leaders in the colony had attended Cambridge University—but one consistent with the prevailing Puritan philosophy. The College was never affiliated with any particular denomination, but many of its earliest graduates went on to become clergymen in Congregational and Unitarian churches throughout New England.[18] An early brochure, published in 1643, justified the College's existence: "To advance Learning and perpetuate it to Posterity; dreading to leave an illiterate Ministery to the Churche". [19] Harvard is governed by two boards, one of which is the President and Fellows of Harvard College, also known as the Harvard Corporation, founded in 1650, and the other is the Harvard Board of Overseers. The President of Harvard University is the day-to-day administrator of Harvard and is appointed by and responsible to the Harvard Corporation. There are 16,000 staff and faculty.[39] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_university_in_the_United_States Harvard University calls itself "the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States" and this claim is rarely challenged. William & Mary calls itself "America's second-oldest college", acknowledging Harvard's claim but in fact adding that it is William & Mary that is the nation's oldest college in its "antecedents". It is possible to quibble over what year should be taken as Harvard's "real" founding date (Harvard uses the earliest possible one, 1636, when the institution was chartered by the Massachusetts Bay Colony). However, Harvard has operated since 1650 under the same corporation, the "President and Fellows of Harvard College"; thus Harvard has an unbroken continuous institutional history dating back that far. One official Harvard web page for the Division of Engineering and Applied Sciences [3] chooses to phrase this claim: "Founded in 1636, Harvard is America's oldest university.“