Charles Bailyn`s Slides - College of Literature, Science, and the Arts

advertisement

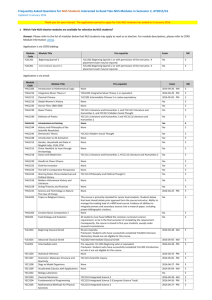

Charles Bailyn Dean of the Faculty A Liberal Arts Curriculum for the 21st Century: Implications for Established Research Universities Introducing Yale-NUS College, a newly founded residential liberal arts college in Singapore. Why this now? Curriculum Development: Process and Results Reflections and Implications Yale-NUS College “An autonomous institution within the National University of Singapore” – not a Yale branch campus Child of two parents… Governing Board: half Yale appointees, half NUS Funded by the Singapore Ministry of Education Leadership from Yale, NUS and elsewhere Separate faculty (tenured and tenure track) Campus adjacent to NUS Opening in August 2013 with 150 students and 50 faculty members Students >50% from Singapore (full financial aid for international students) Faculty ~½ from US, ~¼ from S’pore (incl PRs), ~¼ other Eventual size: 1000 students and 100 faculty Yale-NUS College Yale-NUS College Curriculum Development A true blank slate! (NOT a branch campus…) In the past year, 3 dozen Yale-NUS faculty worked together in New Haven in an “incubation year” to consider a liberal arts curriculum for a global institution in the 21st century. Curriculum report “A New Community of Learning” available on-line (google “Yale-NUS curriculum report”) or hard copy from me - A new residential liberal arts college? Why?? A new residential liberal arts college? Why?? In New Haven in 1828: The two great points to be gained in an intellectual culture are the discipline and the furniture of the mind; expanding its powers, and storing it with knowledge. – Jeremiah Day in the “Yale Report” A new residential liberal arts college? Why?? In New Haven in 1828: The two great points to be gained in an intellectual culture are the discipline and the furniture of the mind; expanding its powers, and storing it with knowledge. – Jeremiah Day in the “Yale Report” A new residential liberal arts college? Why?? In New Haven in 1828: The two great points to be gained in an intellectual culture are the discipline and the furniture of the mind; expanding its powers, and storing it with knowledge. – Jeremiah Day in the “Yale Report” In the 21st century, “furniture” (=information) is readily available to all; but “discipline” is more important than ever A “Community of Learning” featuring “Articulate Communication” Articulate Communication Writing, speaking, visualization Formal and informal, many modes To varied audiences Teachers Peers and team members “Students” Public at large Applies to faculty also! Something to talk about – the Common Curriculum Arguments for a CC, as opposed to a distribution system Creates an intellectual community – for students and faculty Avoids silos and student comfort zones Distinguishes between broad education and a series of introductions to disciplines Broader than traditional “core” curricula Embedding non-western traditions from the start Including the social sciences and the sciences Something to talk about – the Common Curriculum Coverage vs. Representation: the canon vs. the bullpen The problem of coherent juxtapositions Monolithic Dialogic Thematic Instructor autonomy Added material or projects Segmented courses Preparation vs completion – a first course, or a last? Yale-NUS Curriculum: Common Curriculum Year 1: Literature and Humanities I, II Philosophy & Political Thought I, II Scientific Inquiry (1st semester) Comparative Social Institutions (1st semester) Quantitative Reasoning (2nd semester) (Integrated Science) (2nd semester) Year 2: Modern Social Thought (1st semester) Integrated Science (x2) or Foundations of Science (x2) Year 3 or 4: Historical Immersion Current Issues Yale-NUS Curriculum: Common Curriculum Year 1: Literature and Humanities I, II Philosophy & Political Thought I, II Scientific Inquiry (1st semester) Comparative Social Institutions (1st semester) Quantitative Reasoning (2nd semester) (Integrated Science) (2nd semester) Year 2: Modern Social Thought (1st semester) Integrated Science (x2) or Foundations of Science (x2) Year 3 or 4: Historical Immersion Current Issues Yale-NUS Curriculum: Comparative Social Institutions Topics: Culture and Thought Markets Religion Family City Polity & Regime Race & Ethnicity Approaches: Multiple Disciplines Lectures Contextualized Readings Visualizations (Maps & Charts) Experiments and Games Discussions Reports: Written, Oral, Pictorial Yale-NUS Curriculum: Electives Pure electives Arts Skills Others Outside courses NUS courses Other institutions Courses toward a minor Courses within another major Additional courses in the major Yale-NUS Curriculum: Majors and Minors NO DISCIPLINARY DEPARTMENTS! Categories of majors/minors Traditional disciplines (History, Philosophy, Economics, Psychology, Anthropology) Broader paths (Literature, Life Sci, Phys Sci, Math/Comp) Interdisciplinary (Arts & Hum, PPE, Env Studies, Urban Studies, Global Affairs) Capstone projects: not necessarily purely academic, communicated to various audiences Reflections on Traditional Research Universities Question: why couldn’t one simply do all this at Yale (or similar institutions)? (With apologies for texty slides!) Reflections on Traditional Research Universities: 1 Most existing curricula are the sum over decisions by individuals and departments. The curriculum is “owned” by the faculty, but not collectively. Collective action is often viewed as an administrative incursion into faculty autonomy – and there is some truth in this. Alumni also represent a force for stasis. Evolution at the systemic level is therefore very difficult. As far as I can tell, no university has significantly changed the broad structure of its undergraduate curriculum in many years, although there are significant differences between institutions. Reflections on Traditional Research Universities: 2 Research vs teaching is a problem, but not as usually construed. It’s not a matter of the time budget of individuals, but of institutional structures such as disciplinary departments and distribution systems. Many of these arose from the “Eliot compromise” which enabled liberal arts colleges to co-exist with research universities. By the implicit terms of this compromise, faculty could do research and teach on whatever they like. The justification for undergraduate education in this model rests largely on proximity to expertise, which is becoming much less important. Reflections on Traditional Research Universities: 3 There has traditionally been no path to prominence through teaching. In research, faculty can aspire to prominence demonstrated by prizes and recognition within their discipline. The relevant community of judgment is located outside any particular educational institution. Those interested in university service (aka administration) can aspire to a variety of leadership positions, with their associated psychic and material rewards. But it is hard to identify such a track for those interested in prominence in pedagogy and teaching. Recently, a new possibility has arisen, namely “MOOC gurus”, which pushes directly against the values of on-campus “articulate communication”. Possible Paths Forward Two-tiered faculty, one attuned to the broadly-distributed community of judgment of research, one attuned to local pedagogical priorities. BAD TRACK RECORD! (e.g. post-war Japan). “University Teaching Professors” Given “research relief” (= $$) Additional undergraduate teaching Real control over significant portions of undergraduate curriculum Must be seen as representing the faculty Give up on the Eliot compromise More To Come!