The Awakening Powerpoint

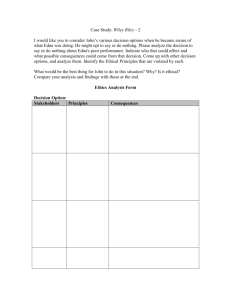

advertisement

Never let your husband have cause to complain that you are more agreeable abroad than at home; nor permit him to see in you an object of admiration as respects your dress and manners, when in company, while you are negligent of both in the domestic circle…Nothing can be more senseless than the conduct of a young woman, who seeks to be admired in general society for her politeness and engaging manners, or skill in music, when, at the same time, she makes no effort to render her home attractive; and yet that home whether a place or a cottage, is the very centre of her being—the nucleus around which her affections should revolve, and beyond which she has comparatively small concern. From Decorum: A Practical Treatise on Etiquette and Dress of the Best American Society by Richard A. Wells, 1886 Beware of trusting any individual whatever with small annoyances, or misunderstandings, between your husband and yourself, if they unhappily occur. Confidants are dangerous persons, and many seek to obtain an ascendancy in families by gaining the good opinion of young married women. From Decorum: A Practical Treatise on Etiquette and Dress of the Best American Society by Richard A. Wells, 1886 Let nothing, but the most imperative duty, call you out upon your reception day. Your callers are, in a measure, invited guests, and it will be an insulting mark of rudeness to be out when they call. Nether can you be excused, except in case of sickness. From The Ladies Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness by Florence Hartley, 1860 The true lady walks the street, wrapped in a mantle of proper reserve, so impenetrable that insult and coarse familiarity shrink from her, while she, at the same time, carries with her a congenial atmosphere which attracts all, and puts all at their ease…A lady walks quietly through the streets, seeing and hearing nothing that she ought not see or hear, recognizing acquaintances with a courteous bow, and friends with words of greeting. She is always unobtrusive, never talks loudly, or laughs boisterously, or does anything to attract the attention of passers-by. She walks along in her own quiet, lady-like way, and by her preoccupation is secure from any annoyance to which a person of less perfect breeding might be subjected. From Our Deportment, Or the Manners, Conduct, and Dress of the Most Refined Society by John H. Young, 1882 • The best way to make up a bathing suit is with full short trousers or knickerbockers gartered above the knee, and a short skirt made with gored front breadth, a little fullness over the hips, and considerable fullness in the back. • From “New York Fashions” in Harper’s Bazaar, June 1898 Who is…. • Leonce • Adele • Robert • Edna • On page 548, the narrator says that Edna’s marriage to Leonce was “purely an accident.” How can a marriage be “an accident”? Does Edna love Leonce? • “An indescribable oppression, which seemed to generate in some unfamiliar part of her consciousness, filled her whole being with a vague anguish” (539). Can we describe this “indescribable anguish”? Why is it birth place unfamiliar? And “anguish” about what? • “A certain light was beginning to dawn dimly within her,--the light which, showing the way, forbids it” (544). • “Mrs. Pontellier was beginning to realize her position in the universe as a human being, and to recognize her relations as an individual to the world within and about her” (544). • “Edna began to feel like one who awakens gradually out of a dream, a delicious, grotesque, impossible dream, to feel again the realities pressing into her soul” (559). • What is this “light,” this “realization,” this “recognition, that Edna is awakening to? How is it an “awakening”? Why is it “delicious, grotesque, [and] impossible? • On page 571, Edna tells Adele, “I would give up the unessential; I would give my money, I would give my life for my children; but I wouldn’t give myself.” How can giving up one’s life not be giving up something essential? What is she referring to when she tells Adele that a mother can sacrifice more than her life for her children? • Leonce wonders if Edna is becoming “mentally unbalanced” and claims that it is apparent to him that she is not “herself”. What causes these realizations? Is he right? • Edna believes that Adele’s marriage to her husband (a man Edna describes as “the salt of the earth” with boundless cheer, charity, and commonsense) is a “fusion of two human beings into one” (676). Nevertheless, after dining with the couple and witnessing their marital harmony and happiness first hand, Edna leaves “depressed rather than soothed”—not because of jealousy, but because of “a pity for that colorless existence which never uplifted its possessor beyond the region of blind contentment, in which no moment of anguish ever visited her soul, in which she would never have the taste of life’s delirium” (677). Is there something to Edna’s observation and judgment or is she merely something of a malcontent, a kind of perpetual “sad sack” that would never find any relationship satisfactory?