EtchbergerASMCUE_10poster - the Biology Scholars Program

advertisement

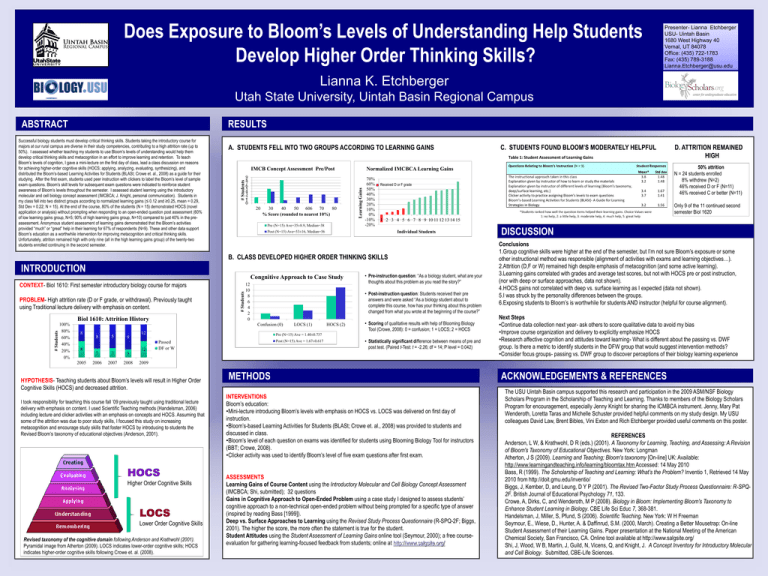

Does Exposure to Bloom’s Levels of Understanding Help Students Develop Higher Order Thinking Skills? Presenter- Lianna Etchberger USU- Uintah Basin 1680 West Highway 40 Vernal, UT 84078 Office: (435) 722-1783 Fax: (435) 789-3188 Lianna.Etchberger@usu.edu Lianna K. Etchberger Utah State University, Uintah Basin Regional Campus RESULTS A. STUDENTS FELL INTO TWO GROUPS ACCORDING TO LEARNING GAINS IMCB Concept Assessment Pre/Post 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 20 30 40 50 606 70 80 % Score (rounded to nearest 10%) Pre (N=15) Ave=35±8.9, Median=38 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% -10% -20% Only 9 of the 11 continued second semester Biol 1620 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Individual Students B. CLASS DEVELOPED HIGHER ORDER THINKING SKILLS Congnitive Approach to Case Study PROBLEM- High attrition rate (D or F grade, or withdrawal). Previously taught using Traditional lecture delivery with emphasis on content. # Students Biol 1610: Attrition History 100% 80% 60% 40% 20% 0% # Students CONTEXT- Biol 1610: First semester introductory biology course for majors 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 8 8 2005 8 5 12 3 2 3 2006 2007 2008 LOCS (1) HOCS (2) • Scoring of qualitative results with help of Blooming Biology Tool (Crowe, 2008): 0 = confusion; 1 = LOCS; 2 = HOCS Pre (N=15) Ave = 1.40±0.737 9 12 • Pre-instruction question: “As a biology student, what are your thoughts about this problem as you read the story?” • Post-instruction question: Students received their pre answers and were asked “As a biology student about to complete this course, how has your thinking about this problem changed from what you wrote at the beginning of the course?” Confusion (0) Post (N=15) Ave = 1.67±0.617 Passed DF or W D. ATTRITION REMAINED HIGH 50% attrition N = 24 students enrolled 8% withdrew (N=2) 46% received D or F (N=11) 46% received C or better (N=11) Received D or F grade Post (N=15) Ave=53±16, Median=56 INTRODUCTION C. STUDENTS FOUND BLOOM’S MODERATELY HELPFUL Normalized IMCBCA Learning Gains Learning Gains Successful biology students must develop critical thinking skills. Students taking the introductory course for majors at our rural campus are diverse in their study competencies, contributing to a high attrition rate (up to 50%). I assessed whether teaching my students to use Bloom’s levels of understanding would help them develop critical thinking skills and metacognition in an effort to improve learning and retention. To teach Bloom’s levels of cognition, I gave a mini-lecture on the first day of class, lead a class discussion on reasons for achieving higher-order cognitive skills (HOCS; applying, analyzing, evaluating, synthesizing), and distributed the Bloom’s-based Learning Activities for Students (BLASt; Crowe et. al., 2008) as a guide for their studying. After the first exam, students used peer instruction with clickers to label the Bloom’s level of sample exam questions. Bloom’s skill levels for subsequent exam questions were indicated to reinforce student awareness of Bloom’s levels throughout the semester. I assessed student learning using the introductory molecular and cell biology concept assessment (IMCBCA; J. Knight, personal communication). Students in my class fell into two distinct groups according to normalized learning gains (≤ 0.12 and ≥0.25, mean = 0.29, Std Dev = 0.22; N = 15). At the end of the course, 80% of the students (N = 15) demonstrated HOCS (novel application or analysis) without prompting when responding to an open-ended question post assessment (60% of low learning gains group, N=5; 90% of high learning gains group, N=10) compared to just 40% in the preassessment. Anonymous student assessment of learning gains demonstrated that the Bloom’s activities provided “much” or “great” help in their learning for 67% of respondents (N=9). These and other data support Bloom’s education as a worthwhile intervention for improving metacognition and critical thinking skills. Unfortunately, attrition remained high with only nine (all in the high learning gains group) of the twenty-two students enrolled continuing in the second semester. # Students ABSTRACT • Statistically significant difference between means of pre and post test. (Paired t-Test: t = -2.26; df = 14; P level = 0.042) DISCUSSION Conclusions 1.Group cognitive skills were higher at the end of the semester, but I’m not sure Bloom’s exposure or some other instructional method was responsible (alignment of activities with exams and learning objectives…). 2.Attrition (D,F or W) remained high despite emphasis of metacognition (and some active learning). 3.Learning gains correlated with grades and average test scores, but not with HOCS pre or post instruction, (nor with deep or surface approaches, data not shown). 4.HOCS gains not correlated with deep vs. surface learning as I expected (data not shown). 5.I was struck by the personality differences between the groups. 6.Exposing students to Bloom’s is worthwhile for students AND instructor (helpful for course alignment). Next Steps •Continue data collection next year- ask others to score qualitative data to avoid my bias •Improve course organization and delivery to explicitly emphasize HOCS •Research affective cognition and attitudes toward learning- What is different about the passing vs. DWF group. Is there a metric to identify students in the DFW group that would suggest intervention methods? •Consider focus groups- passing vs. DWF group to discover perceptions of their biology learning experience 2009 HYPOTHESIS- Teaching students about Bloom’s levels will result in Higher Order Cognitive Skills (HOCS) and decreased attrition. I took responsibility for teaching this course fall ’09 previously taught using traditional lecture delivery with emphasis on content. I used Scientific Teaching methods (Handelsman, 2006) including lecture and clicker activities with an emphasis on concepts and HOCS. Assuming that some of the attrition was due to poor study skills, I focused this study on increasing metacognition and encourage study skills that foster HOCS by introducing to students the Revised Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (Anderson, 2001). Higher Order Cognitive Skills Lower Order Cognitive Skills Revised taxonomy of the cognitive domain following Anderson and Krathwohl (2001). Pyramidal image from Atherton (2009). LOCS indicates lower-order cognitive skills; HOCS indicates higher-order cognitive skills following Crowe et. al. (2008). METHODS INTERVENTIONS Bloom’s education: •Mini-lecture introducing Bloom’s levels with emphasis on HOCS vs. LOCS was delivered on first day of instruction. •Bloom’s-based Learning Activities for Students (BLASt; Crowe et. al., 2008) was provided to students and discussed in class. •Bloom’s level of each question on exams was identified for students using Blooming Biology Tool for instructors (BBT; Crowe, 2008). •Clicker activity was used to identify Bloom’s level of five exam questions after first exam. ASSESSMENTS Learning Gains of Course Content using the Introductory Molecular and Cell Biology Concept Assessment (IMCBCA; Shi, submitted); 32 questions Gains in Cognitive Approach to Open-Ended Problem using a case study I designed to assess students’ cognitive approach to a non-technical open-ended problem without being prompted for a specific type of answer (inspired by reading Bass [1999]). Deep vs. Surface Approaches to Learning using the Revised Study Process Questionnaire (R-SPQ-2F; Biggs, 2001). The higher the score, the more often the statement is true for the student. Student Attitudes using the Student Assessment of Learning Gains online tool (Seymour, 2000); a free courseevaluation for gathering learning-focused feedback from students; online at http://www.salgsite.org/ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS & REFERENCES The USU Uintah Basin campus supported this research and participation in the 2009 ASM/NSF Biology Scholars Program in the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. Thanks to members of the Biology Scholars Program for encouragement, especially Jenny Knight for sharing the ICMBCA instrument. Jenny, Mary Pat Wenderoth, Loretta Taras and Michelle Schuster provided helpful comments on my study design. My USU colleagues David Law, Brent Bibles, Vini Exton and Rich Etchberger provided useful comments on this poster. REFERENCES Anderson, L W, & Krathwohl, D R (eds.) (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman Atherton, J S (2009). Learning and Teaching; Bloom's taxonomy [On-line] UK: Available: http://www.learningandteaching.info/learning/bloomtax.htm Accessed: 14 May 2010 Bass, R (1999). The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning: What’s the Problem? Inventio 1, Retrieved 14 May 2010 from http://doit.gmu.edu/inventio/ Biggs, J, Kember, D, and Leung, D Y P (2001). The Revised Two-Factor Study Process Questionnaire: R-SPQ2F. British Journal of Educational Psychology 71, 133. Crowe, A, Dirks, C, and Wenderoth, M P (2008). Biology in Bloom: Implementing Bloom's Taxonomy to Enhance Student Learning in Biology. CBE Life Sci Educ 7, 368-381. Handelsman, J, Miller, S, Pfund, S (2006). Scientific Teaching. New York: W H Freeman Seymour, E., Wiese, D., Hunter, A. & Daffinrud, S.M. (2000, March). Creating a Better Mousetrap: On-line Student Assessment of their Learning Gains. Paper presentation at the National Meeting of the American Chemical Society, San Francisco, CA. Online tool available at http://www.salgsite.org/ Shi, J, Wood, W B, Martin, J, Guild, N, Vicens, Q, and Knight, J. A Concept Inventory for Introductory Molecular and Cell Biology. Submitted, CBE-Life Sciences.