Slide Show #7

advertisement

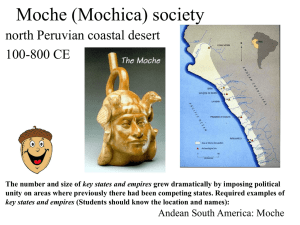

The Great Empires Slideshow #7 Review Questions 1.) WHY WERE trade routes so important to axial-age empires? What were the advantages of land routes and sea routes? Where were they located? 2.) HOW DID the Persian Empire benefit its inhabitants? 3.) HOW WAS Rome able to conquer and rule a vast empire? 4.) HOW DID Asoka seek to unify his empire? 5.) WHAT WAS the significance of the Han dynasty for China? 6.) WHERE DID the first potentially imperial states arise in the Americas? Trade during the Axial Age Desire for luxury goods: silks, spices and herbs, horses, precious stones, cotton and linen, etc. Sea routes across the Indian Sea Monsoon winds Land routes across Eurasia Dangers of piracy and raiders High value, low bulk goods Control over trade routes Persia: Control over Western and Central Eurasia Rome: War with Carthage and with Hellenistic Greek states Control of the Mediterranean China: Building of Great Wall threats from northern raiders such as the Xiongnu; major wars and expansion during Han dynasty protects trade routes China and Rome--Silk Roads. A face with Caucasian features on a woolen weaving from the first or second century C.E. is evidence that the Chinese and the Romans were linked by trade. The cloth was discovered in a grave on the Silk Roads in Xinjiang. The face was stitched into a pair of pants and woven in a style not used by the Chinese. Trade Routes to the East: Silk Roads Empire Building Persia: Building of roads and infrastructure Rome: Massive road building, enormous expenditures on infrastructure (public markets, theaters, govt. buildings, etc.) facilitating trade China: Similar expenditures as in Rome, with even more rational and centralized bureaucracy India: Asoka runs centralized state Integrating economy, government, religion (Buddhism) Romans and Barbarians The Roman general who dominates the composition—in the center, with arm outstretched—was buried inside this magnificent sarcophagus of the mid–third century C.E. Bearded Germans succumb beneath the horses’ hooves of the clean-shaven Romans. In reality, the Germans were not so easy to defeat. Tombstone of Roman Soldier The Roman Empire moved people across vast distances. This tombstone in Cologne, Germany, records a veteran soldier, Marcus Valerius Celerinus, who married and settled locally after his legion was transferred to Germany from his home in Écija in southern Spain, late in the first century C.E. Roman Aqueduct at Segovia, Spain Nearly 3,000 feet long and rising to 115 feet high, the second-century C.E. aqueduct is one of the surviving marvels of Roman engineering. In laying the infrastructure of communications and supply, the Romans were not only building up their own power and their ability to shift and sustain armies, they were also demonstrating the benefits, self-confidence, and durability of their rule for subject peoples The Celts This wine vessel, buried with a high-ranking woman in the mid-first millennium B.C.E., was as tall as she was. Like the wine it contained, it was imported from the Mediterranean. Greek soldiers and chariots decorate the rim. Serpent-haired Gorgons form handles, inside which lions climb—all symbolizing the owner’s power. Egypt: Fayyum portrait When Egypt became a Roman province in 30 B.C.E., burial practices remained the same: Mummies were encased in painted caskets. But the style of painting that depicted the deceased gradually took on Roman conventions of portraiture, as in this lovely example of a young woman from the mid–second century C.E. Persepolis. Reliefs that line the approach to the audience chamber of the ruler of Persia at Persepolis show exactly what went on there: reception of tribute, submission of ambassadors. The figures look uniform at first, but their various styles of beards, headgear, and robes indicate the diversity of the lands from which they came and, therefore, the range of the Great King’s power. Terracotta warriors at Xian, Shaanxi Province Though his life and reign were short, everything else about Shi Huangdi (r. 221–210 B.C.E.), the Qin ruler who conquered China, was on a monumental scale. The size and magnificence of his tomb, guarded by an army of terracotta warriors, echoes the grandeur of his engineering works and the scope of his ambitions and uncompromising reforms. Terracotta Army, Xian, Shaanxi Province Spread of Ideas Persia: Conquest by Alexander the Great c. 335 BCE India: Asoka’s empire spreads Buddhism, Buddhism spreads east into Southeast Asia, China, Korea, and Japan Trade routes, monasteries Rome: Christianity spreads and develops system created by Persian empire facilites spread of Greek culture Greek-influenced art, coins begins to appear in India. Mediterranean region: along the trade routes and Rome’s imperial cities. Across Asia into China as a result of the land and sea routes of trade China: Confucianism & Daoism spread to Korea, Japan, Also influences many Central Asian peoples Meanwhile Central Asian (Nomadic) culture influences China Heavenly horse. Chinese artists have favored horses as subjects in almost every period, but never more than during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.), when an intense effort to import fine horses from Central Asia enriched China’s equine bloodstock. More than for their utility, horses inspired artists—as in this example from Wuwei (Gansu province) of the second century C.E.—as symbols of the fleeting, everchanging nature of human life. The Art Archive/Picture Desk, Inc./Kobal Collection The Empire of Alexander the Great Gandharan sculpture. Soldiers of Alexander the Great (r. 336–323 B.C.E.) founded the kingdom of Gandhara. Greek influence is unmistakable in its art: in the realistic modeling,, the deep reliefs. Buddhist piety dominates the subject matter. Here the artist illustrates the legend of how King Sibi became a Buddha by sacrificing his eyes and flesh to save the life of a pigeon while gods look on. General Wudi worships the Buddha. In the early second century B.C.E., shortly after the founding of Dunhuang, the Chinese General Wudi invaded Central Asia along the Silk Roads in search of horses. “Two golden men” were among the other booty he captured. Buddhist painters at Dunhuang assumed that these statues were Buddhas and depicted Wudi worshipping them. The Stupa of Sanchi The Emperor Asoka (r. ca. 272–223 B.C.E..) built the first shrine at Sanchi, in India, to honor a place made holy by the footprints of the Buddha. Enriched by the donations of pilgrims, it was adorned by dozens of elaborate structures over thousands of years. The northern gateway, shown here, is elaborately carved with scenes of legends of the Buddha’s life and with tales of exemplary charity. Note the elephants and tree spirits, in the form of dancers entwined with mango trees, who hold up the upper crossbeams. Collapse of Empires, Not Trade or Ideas Although each empire collapsed in its turn because of problems in communication, the military, the economy, or over-centralization, none of the ideas that were spread because of these empires died out. These ideas were stronger than the might of powerful states. Today’s Question Is America an empire? Consider The global reach of American armed forces American willingness to use that force in its own interests, sometimes at the expense of the interests of the global community On the other hand, consider The vast difference in political philosophy behind the U.S and empires such as Rome or Han China The limits of America’s ability to dominate the world Is America in some sense an imperial power today? More usefully, what opportunities and dangers for the use of American influence would an affirmative answer to this question imply, in light of the history of the great empires of the classical world?