Stephen Crane

advertisement

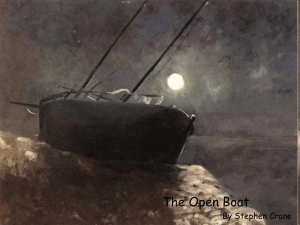

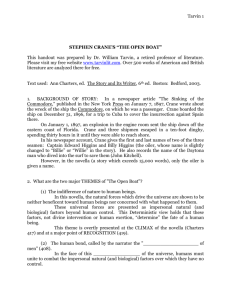

Stephen Crane Naturalism “The Open Boat” (1897) Hao Guilian, Ph,D. Yunnan Normal University Sept, 2009 AMERICAN NATURALISM When Charles Darwin published The Descent of Man in 1871, he challenged the fundamental beliefs of most people by asserting that humans and apes had evolved from a common ancestor. Many critics of Darwin misunderstood his theory to mean that people had descended directly from apes. This caricature of Charles Darwin as an ape appeared in the London Sketch Book in 1874. Naturalist Characters A thoroughly different sense of character emerges: - dehumanized - determined - moved by inner and outer forces beyond conscious moral control American Naturalists Lacked any sense of common purpose No self-conscious 'school’ Shared in common an attraction to the philosophical determinism This concept that inspired the new narrative conceptions of setting and character was fully incorporated in the works of four American writers - Frank Norris, Stephen Crane, Theodore Dreiser and Jack London Stephen Crane (1871-1900) an American novelist, short story writer, poet and journalist. Prolific throughout his short life, he wrote notable works in the Realist tradition as well as early examples of American Naturalism and Impressionism. He is recognized by modern critics as one of the most innovative writers of his generation. Stephen Crane (1871-1900) Writer most famous for novel The Red Badge of Courage (1895), about a young man’s experience of Civil War The most bleakly nihilistic of the group Created the most clearly self-conscious body of work Early novel, Maggie, A Girl of the Streets (1893), set in slums of New York; also wrote short stories and poetry After Red Badge, became correspondent in Cuban insurrection, 1897 Stephen Crane (1871-1900) Jan. 1897: En route to Cuba, steamer The Commodore sank off Florida; Crane published newspaper account and later the short story “The Open Boat” 1897: Settled in England with Cora Howard, who had been madam of a brothel in Florida. Became friend of writer Henry James 1900: Died of tuberculosis in Germany The Commodore Nature vs. Civilization About the indifference of nature and the necessity for each person to confront that indifference independently About the ability of people to work together to make meaning (be civilized) despite nature’s indifference Crane’s Art Naturalism Realism Impressionism And the stylistic technique of Stephen Crane is similar to the impressionist painting, especially in the use of color and the chiaroscuro. There is a strong connection in the novel between humankind and nature, a frequent and prominent concern in Crane's fiction and poetry throughout his career. Whereas contemporary writers (Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry David Thoreau) focused on a sympathetic bond on the two elements, Crane wrote from the perspective that human consciousness distanced humans from nature. In The Red Badge of Courage, this distance is paired with a great number of references to animals, and men with animalistic characteristics: people "howl", "squawk", "growl", or "snarl".Since the resurgence of Crane's popularity in the 1920s, The Red Badge of Courage has been deemed a major American text. Hemingway once wrote that the novel "is one of the finest books of our literature, … because it is all as much of a piece as a great poem is." “The sun swung steadily up the sky, and they knew it was broad day because the color of the sea changed from slate to emerald green streaked with amber lights, and the foam was like tumbling snow.” (The Open Boat, paragraph 11) “The sea and sky were each of the gray hue of the dawning. Later, carmine and gold was painted upon the waters. The morning appeared finally, in its splendor, with a sky of pure blue,” (The Open Boat, paragraph 201) Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise The works of Stephen Crane Novel: Maggie: A Girl of the Streets (1893) The Red Badge of Courage (1895) George's Mother (1896) The Third Violet (1896) Active Service (1899) The O'Ruddy (1903) Maggie: A Girl of the Street The Red badge of Courage The Open Boat Crane’s technique (pp.104-21) Perception “None of them knew the color of the sky. Their eyes glanced level, and were fastened upon the waves that swept toward them” (104) In the wan light, the faces of the men must have been gray. Their eyes must have glinted in strange ways as they gazed steadily astern. Viewed from a balcony, the whole thing would doubtlessly have been weirdly picturesque. But the men in the boat had no time to see it (105) Simile & Metaphor “Many a man ought to have a bath-tub larger than the boat which here rode upon the sea” (104) “A seat in this boat was not unlike a seat upon a bucking broncho, and, by the same token, a broncho is not much smaller” (105) Cook: “Wouldn't have a show” without on-shore wind (106) “they now rode this wild colt of a dingey like circus men” (109) Bucking Bronco Characters Cook: fat; a talker: “Gawd!”; looks at sea (104) Cheerful (107) Irrelevant talk: “what kind of pie” (114) Oiler: more physical, swift; a worker; quiet Rows more than anyone else: “And the oiler rowed, and then the correspondent rowed. Then the oiler rowed” (111) Focuses on work; sees least: “all but the oarsman watched the shore grow” (109) Characters Captain: “mind . . . rooted deep in the timbers” of sunken ship (104) “impression of a scene” (7 faces—the 7 men who died) Becomes the captain of the dingy—still commands respect Correspondent: “wondered why he was there”: an outsider, a thinker (104) based on Crane himself; the main center of consciousness” “cynical of men” (730); sarcastic and cursing Characters See conversation at end of section 1 (105): "Houses of refuge don't have crews," said the correspondent. "As I understand them, they are only places where clothes and grub are stored for the benefit of shipwrecked people. They don't carry crews." "Oh, yes, they do," said the cook. "No, they don't," said the correspondent. "Well, we're not there yet, anyhow," said the oiler, in the stern. Interpretation: Boat & Shore Unbridgeable divide between the men and the shore: men in boat misinterpret the shore; people on shore misinterpret the men (111-13): "Well, I wish I could make something out of those signals. What do you suppose he means?" "He don't mean anything. He's just playing." Interpretation: Boat & Shore Men’s repeated reflection: “If I am going to be drowned -- if I am going to be drowned -- if I am going to be drowned, why, in the name of the seven mad gods who rule the sea, was I allowed to come thus far and contemplate sand and trees? Was I brought here merely to have my nose dragged away as I was about to nibble the sacred cheese of life?” (110) Interpretation: Men & Nature The men here do not communicate well with nature: “nature does not regard him as important” (116) (but waves are “important”) Nature lacks “visible expression” or “personification” to communicate with (116): Gull is an “Ugly brute” as if “made with a jack-knife” (106) Shark is a “thing” (116) Interpretation: Men & Nature The correspondent finds his own “visible expression” of nature in the “wind-tower”: “This tower was a giant, standing with its back to the plight of the ants. It represented in a degree, to the correspondent, the serenity of nature amid the struggles of the individual -- nature in the wind, and nature in the vision of men. She did not seem cruel to him, nor beneficent, nor treacherous, nor wise. But she was indifferent, flatly indifferent” (118) “Subtle Brotherhood” The men form a community despite nature’s indifference: “It would be difficult to describe the subtle brotherhood of men that was here established on the seas. No one said that it was so. No one mentioned it. But it dwelt in the boat, and each man felt it warm him” (107) “Subtle Brotherhood” However, brotherhood has limits: each character must finally face his individual fate: “The correspondent, observing the others, knew that they were not afraid, but the full meaning of their glances was shrouded” (118) “Perhaps an individual must consider his own death to be the final phenomenon of nature” (120) Return to Land: Characters Oiler: swimming rapidly, “ahead in the race” (119)—characteristic: strength Cook: swims on back—characteristic: size Captain: holds onto boat—characteristic: control of boat Return to Land: Characters Correspondent: “paddled leisurely”; contemplates shore—characteristic: thinking, perception “The shore was set before him like a bit of scenery on a stage, and he looked at it and understood with his eyes each detail of it” (119) Why does the story have no heroism? This is a feature we commonly find in realism / naturalism stories. This is to show readers how insignificant humans are. To emphasize the greatness of the universe Why are there no heroes in this story? The only way to survive is to work together. There is no particular man that can fight against the sea. There are no villains in this story. Why isn’t the man who appears to save the crew in the end a hero? Because the behavior to save people is just a human reaction and the author doesn’t portrait it clearly, that is not hero’s characteristics. Conclusion Why does the oiler not survive? Chance? Too weak from his self-sacrifice? Lack of perception, imagination? Divide between sea and land is bridged Land offers “all the remedies sacred to their minds” (121) Men hear “the great sea’s voice” and “they felt that they could then be interpreters” (121)