Pamuk`s Istanbul

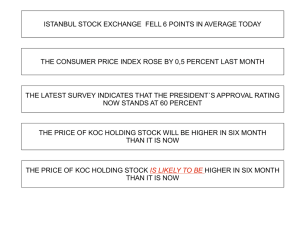

advertisement

Pamuk’s Istanbul Excerpts from Chapter 10 for Enjoyment Huzun: a feeling of deep spiritual loss To the Sufis, huzun is the spiritual anguish we feel because we cannot be close enough to Allah, because we cannot do enough for Allah in this world. A true Sufis follower would take no interest in worldly concerns like death, let alone goods or possessions; he suffers from grief, emptiness, and inadequacy because he can never be close enough to Allah, because his apprehension of Allah is not deep enough. Moreover, it is the absence, not the presence, of huzun that causes him distress. It is the failure to experience huzun that leads him to feel it; he suffers because he has not suffered enough, and it is by following this logic to its conclusion that Islamic culture has come to hold huzun in high esteem. (90—91) Cemaat: community of believers The central preoccupation, as with all classic Islamic thinkers, was the cemaat, or community of believers. (92) Now we begin to understand huzun not as the melancholy of a solitary person but the black mood shared by millions of people together. What I am trying to explain is the huzun of an entire city: of Istanbul. (92) This feeling that is unique to Istanbul and that binds its people together But what I am trying to describe now is not the melancholy of Istanbul but the huzun in which we see ourselves reflected, the huzun we absorb with pride and share as a community. To feel this huzun is to see the scenes, evoke the memories, in which the city itself becomes the very illustration, the very essence, of huzun. (94) The huzun is so dense you can almost touch it These are nothing like the remains of great empires to be seen in western cities, preserved like museums of history and proudly displayed. The people of Istanbul simply carry on with their lives amid the ruins. Many western writers and travelers find this charming. But for the city’s more sensitive and attuned residents, these ruins are reminders that the present city is so poor and confused that it can never again dream of rising to its formerly heights of wealth, power, and culture. It is no more possible to take pride in these neglected buildings, which dirt, dust, and mud have blended into their surroundings, than it is to rejoice in the beautiful old wooden houses that as a child I watched burn down one by one. (101) Huzun by choice Istanbul does not carry its huzun as “an illness for which there is a cure” or “an unbidden pain from which we need to be delivered”: It carries its huzun by choice. And so it finds its way back to the melancholy of Burton, who held that “All other pleasures are empty./ None are as sweet as melancholy”; echoing its self-denigrating wit, it dares to boast of its importance in Istanbul life. (103—104) An ache that finally saves our souls and also give them depth The screen he projects over life is painful because life itself is painful. So it is, also for the residents of Istanbul as they resign themselves to poverty and depression. Imbued still with the honor accorded it in Sufi literature, huzun gives their resignation an air of dignity, but it also explains their choice to embrace failure, indecision, defeat, and poverty so philosophically and with such pride, suggesting that huzun is not the outcome of life’s worries and great losses but their principal cause. (continue to next slide…) So it was for the heroes of the Turkish films of my childhood and youth, and also for many of my real-life heroes during the same period: They all gave the impression that because of this huzun they’d been carrying around in their hearts since birth they could not appear desirous in the face of money, success, or the women they loved. Huzun does not just paralyze the inhabitants of Istanbul; it also gives them poetic license to be paralyzed. (103—104) Feels together and affirms as one The huzun of Istanbul suggests nothing of an individual standing against society; on the contrary, it suggests an erosion of the will to stand against the values and mores of the community and encourages us to be content with little, honoring the virtues of harmony, uniformity, humility. Huzun teaches endurance in times of poverty and deprivation; it also encourages us to read life and the history of the city in reverse. It allows the people of Istanbul to think of defeat and poverty not as a historical end point but as an honorable beginning, fixed long before they were born. So the honor we derive from it can be rather misleading. But it does suggest that Istanbul does not bear its huzun as an incurable illness that has spread throughout the city, as an immutable poverty to be endured like grief, or even as an awkward and perplexing failure to be viewed and judged in black and white; it bear its huzun with honor. (104—105)