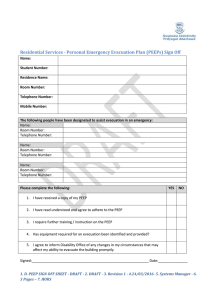

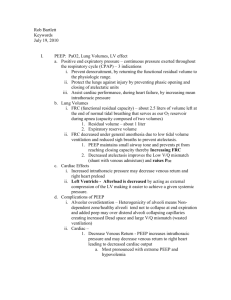

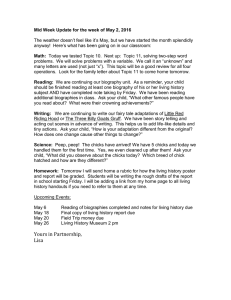

British Journal of Anaesthesia, xxx (xxx): xxx (xxxx) doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2023.08.007 Advance Access Publication Date: xxx Clinical Investigation CLINICAL INVESTIGATION Effect of driving pressure-guided positive end-expiratory pressure on postoperative pulmonary complications in patients undergoing laparoscopic or robotic surgery: a randomised controlled trial Yoon Jung Kim1,2, Bo Rim Kim3 , Hee Won Kim2, Ji-Yoon Jung2 Jeoung-Hwa Seo1,2 , Won Ho Kim1,2 Hyun-Kyu Yoon1,2,* 1 , Hye-Yeon Cho1,2, , Hee-Soo Kim1,2, Suhyun Hwangbo4 and Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 3Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea and 4Department of Genomic Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea *Corresponding author. E-mail: warren83@snu.ac.kr Abstract Background: Individualised positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) improves respiratory mechanics. However, whether PEEP reduces postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) remains unclear. We investigated whether driving pressureguided PEEP reduces PPCs after laparoscopic/robotic abdominal surgery. Methods: This single-centre, randomised controlled trial enrolled patients at risk for PPCs undergoing laparoscopic or robotic lower abdominal surgery. The individualised group received driving pressure-guided PEEP, whereas the comparator group received 5 cm H2O fixed PEEP during surgery. Both groups received a tidal volume of 8 ml kg1 ideal body weight. The primary outcome analysed per protocol was a composite of pulmonary complications (defined by prespecified clinical and radiological criteria) within 7 postoperative days after surgery. Results: Some 384 patients (median age: 67 yr [inter-quartile range: 61e73]; 66 [18%] female) were randomised. Mean (standard deviation) PEEP in patients randomised to individualised PEEP (n¼178) was 13.6 cm H2O (2.1). Individualised PEEP resulted in lower mean driving pressures (14.7 cm H2O [2.6]), compared with 185 patients randomised to standard PEEP (18.4 cm H2O [3.2]; mean difference: -3.7 cm H2O [95% confidence interval (CI): -4.3 to -3.1 cm H2O]; P<0.001). There was no difference in the incidence of pulmonary complications between individualised (25/178 [14.0%]) vs standard PEEP (36/185 [19.5%]; risk ratio [95% CI], 0.72 [0.45e1.15]; P¼0.215). Pulmonary complications as a result of desaturation were less frequent in patients randomised to individualised PEEP (8/178 [4.5%], compared with standard PEEP (30/185 [16.2%], risk ratio [95% CI], 0.28 [0.13e0.59]; P¼0.001). Conclusions: Driving pressure-guided PEEP did not decrease the incidence of pulmonary complications within 7 days of laparoscopic or robotic lower abdominal surgery, although uncertainty remains given the lower than anticipated event rate for the primary outcome. Clinical trial registration: KCT0004888 (http://cris.nih.go.kr, registration date: April 6, 2020). Keywords: driving pressure; lung protective ventilation; pneumoperitoneum; positive end-expiratory pressure; postoperative pulmonary complications Received: 1 February 2023; Accepted: 1 August 2023 © 2023 British Journal of Anaesthesia. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: permissions@elsevier.com 1 2 - Kim et al. Editor’s key points Individualised PEEP determined by a driving pressure-guided intervention might reduce pulmonary complications after laparoscopic/robotic abdominal surgery. This single-centre study randomised 384 patients at risk of postoperative pulmonary complications to receive either driving pressure-guided PEEP or 5 cm H2O fixed PEEP during surgery. Individualised PEEP resulted in 3.7 cm H2O lower mean driving pressure. Pulmonary complications were lower than anticipated but similar between individualised vs standard PEEP. Optimal PEEP settings remain unclear for laparoscopic/robotic abdominal surgery. Over the past few decades, laparoscopic and robotic techniques have become increasingly common approaches for lower abdominal surgery, with the aim of accelerating postoperative recovery.1,2 The combination of pneumoperitoneum with steep Trendelenburg positioning to facilitate lower abdominal/pelvic surgery3 promotes atelectasis and reduces lung compliance and arterial oxygenation.4 Postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) are common in patients undergoing laparoscopic lower abdominal surgery.5 As PPCs prolong hospitalisation and possibly increase mortality,6,7 optimising intraoperative mechanical ventilation strategies may prevent these complications. Intraoperative lung-protective ventilation is associated with reduced PPC incidence.8 Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), a key component of lung-protective ventilation, prevents the closure of small airways and alveolar collapse; thus, ventilationeperfusion mismatch and oxygenation are improved.9 However, large multicentre randomised controlled trials comparing two fixed PEEP values showed no clinically significant differences in PPCs,10,11 which has prompted clinicians to focus on individualised adjustment of PEEP.12 Whereas many studies have investigated the effects of individualised PEEP on clinical outcomes,13e17 the role of individualised PEEP remains unclear. In particular, limited data exist on the association between driving pressure-guided PEEP and PPCs in laparoscopic or robotic lower abdominal surgery. Therefore, in the present study, we investigated the impact of driving pressure-guided PEEP on PPCs in patients scheduled to undergo surgeries requiring pneumoperitoneum with the steep Trendelenburg position. We hypothesised that driving pressure-guided PEEP during surgery would decrease PPCs within 7 postoperative days. Methods Study design This single-centre, randomised controlled trial was approved by the institutional review board of the Seoul National University Hospital (Approval number: 2002-142-1104). The protocol of the present study was registered at the clinical trial registry (http:// cris.nih.go.kr, principal investigator: H-KY, registration date: April 6, 2020, registration number: KCT0004888), and written informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrolment. This study was conducted in compliance with the Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and the manuscript was written in accordance with the applicable Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. Inclusion criteria The patients aged 18 yr with a moderate or high risk of PPCs according to the Assess Respiratory Risk in Surgical Patients in Catalonia (ARISCAT) risk score,6 scheduled to undergo laparoscopic or robotic surgery in the steep Trendelenburg position at a tertiary teaching hospital (Seoul National University Hospital) between April 9, 2020 and September 2, 2022 were eligible. Exclusion criteria We excluded patients with conversion to open surgery, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification 3, history of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), body mass index 35 kg m2, angina, heart failure, increased intracranial pressure, pregnancy, and contraindications to the use of PEEP, including bronchopleural fistula, hypovolemic shock, and right ventricular failure. Randomisation and blinding An investigator not involved in this study generated the random sequence table with a one-to-one ratio using a computer program with a block size of two and four before patient recruitment. The patients were randomly assigned to receive either individualised PEEP based on driving pressure (individualised group) or a fixed PEEP of 5 cm H2O during surgery (standard group). The random allocation sequence was sealed in an opaque envelope and released to the attending anaesthesiologist immediately before the trial. The investigators assessing the primary outcomes were blinded to the group allocation. Both surgeons and patients were also unaware of their respective group allocations. However, the attending anaesthesiologists were not blinded to the study group allocation. Anaesthesia protocol Peripheral pulse oximetry (SpO2), electrocardiography, and noninvasive blood pressure monitoring were performed upon entry to the operating room. After adequate preoxygenation, anaesthesia was induced with a target-controlled infusion of remifentanil (target effect-site concentration of 4 ng ml1) and propofol bolus administration (1.0e2.0 mg kg1). Tracheal intubation was performed after achieving adequate neuromuscular block. Mechanical ventilation started via the volumecontrolled ventilation mode with a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 0.4, tidal volume of 8 ml kg1 for ideal body weight, PEEP of 5 cm H2O, and an inspiratory-to-expiratory (I:E) ratio of 1:2. The respiratory rate was adjusted to maintain an end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) of 4.7e6.0 kPa. The bispectral index was adjusted within 40e60, and the mean blood pressure was maintained within 8e12 kPa (60e90 mm Hg). During the pneumoperitoneum, the degree of neuromuscular block was maintained as deep neuromuscular block, defined as a train-offour of 0 and post-tetanic count 4 using a neuromuscular Driving pressure-guided individualised PEEP monitoring device (TOF-Watch SX, Bluestar Enterprises, Omaha, NE, USA). Extubation was performed after administering sugammadex. The protocol mentioned above was provided identically to patients in both groups. Study protocol Three clinicians, including two primary researchers (YJK and H-KY) and another investigator who was not involved in assessing postoperative clinical outcomes but was part of the study team, were engaged in the intervention process. All intervention processes, including recruitment manoeuvres and decremental PEEP trials, were performed by one of the two experienced researchers. During the intervention, the investigator recorded the intervention results and ensured the accuracy of the intervention process. In the individualised group, the first recruitment manoeuvre was performed after achieving the pneumoperitoneum with the steep Trendelenburg position. The volume-controlled ventilation mode was maintained at a respiratory rate of 15 bpm and an I:E ratio of 1:1 during the recruitment manoeuvre. At each 40-s increment, PEEP was then increased from 5 to 20 cm H2O by 5 cm H2O. The recruitment manoeuvre was followed by a decremental PEEP trial, which was initiated at a PEEP of 20 cm H2O. During this trial, with the same respiratory rate and an I:E ratio of 1:2, PEEP was sequentially reduced from 20 to 5 cm H2O by 2 cm H2O every 30 s. Driving pressure was measured by subtracting the PEEP from the plateau pressure at the end of each step. Individualised PEEP was defined as a PEEP that produced the lowest driving pressure. A second recruitment manoeuvre was performed at the end of the decremental PEEP trial. Individualised PEEP was subsequently applied during the pneumoperitoneum. When the pneumoperitoneum ended, another individualised PEEP was determined using the abovementioned manner. The second individualised PEEP was maintained until the end of the surgery. In the standard group, PEEP was initially set to 5 cm H2O and maintained throughout the surgery.18 As an intraoperative rescue therapy, a recruitment manoeuvre was performed if SpO2 decreased below 95% in the two groups, where PEEP was increased stepwise from 5 to 20 cm H2O at an I:E ratio of 1:1, and FiO2 was increased by 0.1 subsequently. PEEP was increased by 2 cm H2O after the recruitment manoeuvre if SpO2 remained below 95% under an FiO2 of 1.0. If titration or application of PEEP interfered with the surgery or caused severe haemodynamic instability, including hypotension or bradycardia that did not respond with fluid resuscitation and administration of vasoactive drugs, PEEP was changed at the discretion of attending anaesthesiologists and recorded. Ephedrine or phenylephrine was administered in both groups to correct hypotension, defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) <12 kPa, at the discretion of the attending anaesthesiologists. In the postanaesthesia care unit (PACU), an arterial blood gas analysis was performed in room air. If SpO2 decreased by less than 92% in room air, oxygen supply was initiated through a nasal prong or facial mask in both groups. FiO2 was increased if SpO2 was 95% or less despite supplying oxygen. Primary outcome The primary outcome was a composite of pulmonary complications within 7 postoperative days.19 A composite of - 3 pulmonary complications included atelectasis, hypoxaemia, ARDS, pneumonia, pleural effusion, bronchospasm, pneumothorax, aspiration pneumonia, early extubation failure or requirement of reintubation, and postoperative requirements for rescue manoeuvres (Supplementary Table S1). Atelectasis, pleural effusion, and pneumothorax were diagnosed by radiological reports, and others were determined by clinicians. Secondary outcomes Secondary outcomes included the length of hospital stay, admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), length of ICU stay, frequency of hypoxaemia (arterial partial pressure of oxygen [PaO2] <8.0 kPa or SpO2 <90% at room air), and arterial blood gas analyses. Arterial blood gas analysis was performed at the following five time-points: 10 min after anaesthesia induction (T1), 30 min after implementing pneumoperitoneum in the steep Trendelenburg position (T2), 1 h after T2 (T3), 2 h after T2 (T4), and just before emergence in the operating room (T5). The intraoperative ventilatory parameters, including peak inspiratory pressure, plateau pressure, tidal volume, PEEP, dynamic and static compliances, mean blood pressure, and heart rate, were automatically recorded at a 1-min interval in the electronic medical record (EMR) systems. All these records were retrieved from the EMR systems by an investigator blinded to the group assignment. Intraoperative hypotension was defined as a time-weighted average (TWA) SBP of <12 kPa, which was calculated as the area between the threshold (12 kPa) and the curve of the SBP measured at a 1-min interval divided by the total duration of monitoring. Sample size calculation In a previous study on patients with moderate or high risk, according to the ARISCAT risk index, PPC incidence was 51.2% after major abdominal surgery using lung-protective ventilation.20 Assuming a significant difference as a 30% decrease in PPC incidence with a two-sided type I error of 0.05 and a power of 80%, 163 patients were required per group. The dropout rate was expected to be up to 15%; therefore, 192 patients had to be enrolled in each group, with 384 patients in total. Statistical analysis Primary analyses utilised per protocol analysis to obtain a more precise estimate of the efficacy of driving pressure-guided PEEP, including only patients who adhered to the predefined PEEP individualisation protocol. Additionally, we conducted an intention-to-treat analysis as a sensitivity analysis. We summarised the collected data as mean (standard deviation, SD) or median (inter-quartile range) or the number of patients (percentage), as appropriate. The ShapiroeWilk test was used to evaluate the normality of the data. Pearson c2 or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical data. Continuous data were analysed using the Student t-test or ManneWhitney Utest, where appropriate. Because of cell sparsity, the PPC count was deemed a categorical variable and compared using Fisher’s exact test. We used repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) test for respiratory parameters and arterial blood gas analysis results. To investigate the risk factors for PPCs, we conducted a post hoc multivariate logistic regression analysis with a stepwise selection using preoperative and intraoperative variables. Statistical analyses were performed 4 - Kim et al. using R software (version 4.1.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant except for repeated measured parameters. Results Participant characteristics From April 2020 to September 2022, 384 subjects meeting the inclusion criteria were enrolled (Table 1). Twenty-one patients were excluded after allocation (Fig. 1). The final per protocol analysis included the remaining 363 patients (178 and 185 patients in the individualised and standard PEEP groups, respectively). to -3.1 cm H2O]; P<0.001). The peak inspiratory and plateau pressures were also higher with individualised PEEP (Fig. 2). Primary outcome: postoperative pulmonary complications There was no difference in the incidence of PPCs within seven postoperative days between individualised (25/178 [14.0%]) and standard (36/185 [19.5%]) PEEP (risk ratio [95% CI]: 0.72 [0.45e1.15], P¼0.215; Table 3). The incidence of each postoperative complication was also comparable between the two groups. Among patients who developed PPCs within 7 postoperative days, most patients presented only one complication (22/25 [88.0%] and 28/36 [77.8%], respectively). The intention-to-treat analysis findings were similar to the perprotocol analysis (Supplementary Table S4). Effect of individualised driving pressure-guided PEEP intervention Secondary outcomes The mean (SD) PEEP with individualised PEEP was 13.6 (2.1) cm H2O (Table 2). Individualised PEEP resulted in lower driving pressure than standard PEEP (14.7 [2.6] vs 18.4 [3.2] cm H2O, mean difference [95% confidence interval, CI] -3.7 cm H2O [-4.3 The need for rescue interventions for episodes of acute desaturation was less frequent with individualised PEEP (8/178 [4.5%], compared with standard PEEP (30/185 [16.2%], risk ratio [95% CI], 0.28 [0.13e0.59]; P¼0.001). Although there was no Table 1 Comparisons of preoperative subject characteristics between the two groups. Data are mean (standard deviation), median (inter-quartile range), or n (%). APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; ARISCAT, the Assess Respiratory Risk in Surgical Patients in Catalonia; ASA-PS, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity; INR, international normalised ratio. Characteristics Individualised group (n¼178) Standard group (n¼185) Standardised mean difference Age, yr (median [range]) Sex, n (%) Female Male Height, cm Weight, kg Body mass index, kg m2 Current smoker, n (%) ARISCAT risk score Preoperative pulmonary function test FVC, L FEV1, L FEV1/FVC, % ASA-PS classification, n (%) 1 2 Comorbidities, n (%) Hypertension Diabetes mellitus Respiratory disease Chronic liver disease Cardiac disease Thyroid disease Neurologic disease Chronic kidney disease Preoperative laboratory results Haemoglobin, g dl1 Platelet, 1000 mm3 White blood cell count, 1 000 mm3 Prothrombin time, INR Serum creatinine, mg dl1 eGFR, ml min1 1.73 m2 APTT, s Serum albumin, g dl1 C-reactive protein, mg dl1 67 (39e83) 67 (38e87) 0.069 0.047 34 (19.1) 144 (80.9) 164.9 (7.1) 67.3 (9.3) 24.6 (23.0e26.3) 24 (13.5) 26.0 (26.0e26.0) 32 (17.3) 153 (82.7) 166.3 (6.9) 68.6 (9.5) 24.8 (23.0e26.6) 30 (16.2) 26.0 (26.0e26.0) 3.8 (0.7) 2.8 (0.5) 74.0 (7.6) 3.9 (0.8) 2.8 (0.6) 72.8 (7.4) 37 (20.8) 141 (79.2) 43 (23.2) 142 (76.8) 91 (51.1) 29 (16.3) 18 (10.1) 19 (10.7) 9 (5.1) 9 (5.1) 3 (1.7) 8 (4.5) 81 (43.8) 40 (21.6) 20 (10.8) 15 (8.1) 6 (3.2) 18 (9.7) 9 (4.9) 12 (6.5) 0.147 0.136 0.023 0.088 0.091 0.179 0.179 0.088 13.6 (13.0e14.3) 222.0 (189.0e252.5) 5.9 (5.0e6.6) 1.0 (0.1) 0.9 (0.8e1.0) 87.7 (77.2e93.6) 30.3 (3.1) 4.4 (4.3e4.6) 0.2 (0.3) 13.7 (13.0e14.6) 213.0 (186.0e253.0) 5.9 (5.1e7.0) 1.0 (0.1) 0.9 (0.8e1.0) 87.1 (76.9e91.8) 30.2 (2.8) 4.4 (4.2e4.6) 0.2 (0.4) 0.147 0.041 0.050 0.048 0.030 0.035 0.025 0.079 0.044 0.203 0.148 0.023 0.077 0.057 0.075 0.002 0.160 0.059 Enrollment Driving pressure-guided individualised PEEP - 5 Assessed for eligibility (n=518) Excluded (n=134) • Declined to participate (n=65) • Other reasons (n=69) Allocated to the standard group who received a fixed PEEP of 5 cm H2O (n=192) ▪ Received allocated intervention (n=183) ▪ Did not receive allocated intervention (n=9) • Change in surgical plan (n=5) • Cancellation of surgery (n=3) • Not meeting inclusion (n=1) ▪ Received allocated intervention (n=186) ▪ Did not receive allocated intervention (n=6) • Change in surgical plan (n=3) • Cancellation of surgery (n=2) • Not meeting inclusion (n=1) Follow-up Lost to follow-up (n=0) Discontinued intervention (n=5) • Unavailable investigator (n=3) • Protocol violation (n=1) • Intraoperative massive bleeding (n=1) Lost to follow-up (n=1) • Incomplete records at ward (n=1) Discontinued intervention (n=0) Analysed (n=178) • Excluded from analysis (n=0) Analysed (n=185) • Excluded from analysis (n=0) Allocation Allocated to the individualised group who received driving pressure-guided PEEP (n=192) Analysis Randomised (n=384) Fig 1. CONSORT flow diagram. difference in time-weighted hypotension, the number of bolus administrations of vasoactive drugs was more frequent with individualised PEEP (2.1 [2.5] vs standard PEEP 1.5 [1.9]; P¼0.009). Intraoperatively, PaO2 and SaO2 were higher with individualised PEEP (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table S2). Other postoperative clinical outcomes, including respiratory failure, length of hospital stays, ICU admission, and postoperative non-pulmonary complications were similar between the two groups. Post hoc analyses Mean driving pressure (odds ratio [OR], 1.114, 95% CI, 1.024e1.212, P¼0.012), ARISCAT risk score (OR, 1.076, 95% CI, 1.014e1.142, P¼0.015), and intraoperative estimated blood loss (OR, 1.001, 95% CI, 1.000e1.002, P¼0.023) were associated with PPCs (Supplementary Table S3) Discussion In this randomised controlled trial, we failed to demonstrate the beneficial effects of driving pressure-guided individualised PEEP on PPCs for up to 7 days after surgery requiring pneumoperitoneum and steep Trendelenburg position. Although individualised PEEP improved some intraoperative respiratory and arterial blood gas variables, these benefits were not translated into improved postoperative clinical outcomes. The lack of difference in incidence of PPCs between groups may be partly explained by several reasons. First, despite enrolling patients with moderate-to-high risk based on the ARISCAT risk score calculated using the expected duration of surgery, a substantial proportion of patients (84%) had a score of 26, a borderline value for distinguishing between low- and moderate-risk patients. Furthermore, ~61% of patients had actual operation times of <180 min. This unintended inclusion of a significant number of low-medium risk patients resulted in our trial being underpowered. Moreover, unlike a previous study, we excluded patients with an ASA physical status classification 3 because of considerations of patient safety.20 Second, the beneficial effects of intraoperative individualised PEEP may disappear after extubation and not persist after surgery, as reported in several previous studies.13,17,21 Thus, postoperative measures, rather than only intraoperative intervention, may be needed to prevent postoperative atelectasis or decruitment.20 Future well-powered randomised controlled trials to test this hypothesis are warranted. Lastly, driving pressure may not adequately represent the lung strain in laparoscopic or robotic surgical patients because its calculation may be influenced by the properties of the whole respiratory system.22 In robotic 6 - Kim et al. Table 2 Comparisons of intraoperative and postoperative characteristics between the two groups. Data are mean (standard deviation), median (inter-quartile range), or n (%). AUC, the area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TWA, time-weighted average. *Indicates the fluid given the rest of the day of surgery, not including the intraoperative fluid amount. Characteristics Type of surgery, n (%) Prostatectomy Gynaecologic surgery Cystectomy Colorectal surgery Surgical modality, n (%) Laparoscopic surgery Robotic surgery Anaesthesia time, min Surgery time, min Intra-abdominal pressure, kPa Ventilatory parameters Mean positive end-expiratory pressure, cm H2O Mean peak inspiratory pressure, cm H 2O Mean plateau pressure, cm H2O Mean driving pressure, cm H2O Mean tidal volume, ml Mean respiratory rate, bpm Intraoperative fluid management Infused fluid volume, ml Urine output, ml Estimated blood loss, ml Transfusion, n (%) Medications Number of bolus administrations of vasoactive drugs Number of bolus administrations of ephedrine Number of patients who received ephedrine, n (%) Cumulative dose of ephedrine, mg Number of bolus administrations of phenylephrine Number of patients who received phenylephrine, n (%) Cumulative dose of phenylephrine, ug Intraoperative hypotension AUC SBP <12 kPa, kPa min TWA SBP <12 kPa, kPa Rescue intervention because of intraoperative desaturation (95%), n (%) Intraoperative subcutaneous emphysema Postoperative fluid status intake, ml Postoperative day 0* Postoperative day 1 Postoperative day 2 Postoperative day 3 Output, ml Postoperative day 0* Postoperative day 1 Postoperative day 2 Postoperative day 3 P-value Individualised group (n¼178) Standard group (n¼185) Risk ratio, mean, or median difference (95% CI) 129 (72.5) 32 (18.0) 16 (9.0) 1 (0.6) 133 (71.9) 30 (16.2) 21 (11.4) 1 (0.5) 1.01 (0.89e1.14) 1.11 (0.70e1.74) 0.79 (0.43e1.47) 1.04 (0.07e16.49) 29 (16.3) 149 (83.7) 167 (136e223) 135 (105e184) 2.0 (2.0e2.0) 27 (14.6) 158 (85.4) 180 (145e225) 143 (110e180) 2.0 (2.0e2.0) 1.11 (0.69e1.81) 0.98 (0.90e1.07) -13 (-21 to 10) -8 (-20 to 8) 0.00 (0.00e0.00) 0.284 0.359 0.646 13.6 (2.1) 5.1 (0.6) 8.5 (8.1e8.8) <0.001 31.3 (3.9) 26.3 (3.6) 5.0 (4.2e5.8) <0.001 27.7 (4.1) 14.7 (2.6) 483.2 (53.9) 14.3 (1.9) 22.9 (3.3) 18.4 (3.2) 494.5 (54.7) 13.7 (2.6) 4.8 (3.6e6.1) -3.7 (-4.3 to -3.1) -11.3 (-23 to 0.4) 0.6 (0.1e1.1) <0.001 <0.001 0.058 0.005 1050 (750e1450) 219 (191) 240 (159) 0 (0.0) 1050 (800e1450) 223 (214) 339 (273) 1 (0.5) 0 (-175 to 200) -5 (-70 to 61) -99 (-147 to -52) NA 0.598 0.892 <0.001 0.999 2.1 (2.5) 1.5 (1.9) 0.62 (0.15e1.09) 0.009 1.5 (1.6) 1.2 (1.4) 0.31 (-0.01 to 0.63) 0.054 112 (62.9) 103 (55.7) 1.13 (0.95e1.34) 0.194 8.7 (9.5) 0.6 (1.7) 6.5 (8.0) 0.3 (1.0) 2.17 (0.36e3.99) 0.31 (0.02e0.60) 0.019 0.034 37 (20.8) 31 (16.8) 1.24 (0.81e1.91) 0.396 27.2 (86.3) 9.2 (30.0) 17.99 (4.48e31.50) 0.008 3.8 (0.0e8.8) 0.02 (0.00e0.05) 8 (4.5) 3.2 (0.0e7.8) 0.01 (0.00e0.03) 30 (16.2) 0.60 (-0.93 to 2.53) 0.002 (-0.01 to 0.01) 0.28 (0.13e0.59) 0.192 0.159 0.001 11 (6.2) 12 (6.5) 0.95 (0.43e2.10) >0.999 900.0 (700.0e1137.5) 3062.5 (2800.0e3370.0) 2250.0 (1742.5e2560.0) 2070.0 (1650.0e2550.0) 900.0 (700.0e1150.0) 3020.0 (2750.0e3400.0) 2200.0 (1785.0e2650.0) 1960.0 (1580.0e2550.0) 0 (-100 to 84) 42.5 (-80 to 157.5) -50 (-275 to 170) 110 (-100 to 310) 0.837 0.600 0.918 0.345 670.0 (355.0e1145.0) 2372.5 (1845.0e2810.0) 1860.0 (1523.0e2240.0) 1687.5 (1190.0e2180.0) 670.0 (409.0e1010.0) 2305.0 (1695.0e2755.0) 1897.0 (1489.5e2420.0) 1582.5 (950.0e2260.0) 0 (-125 to 105) 67.5 (-153.5 to 259.5) -37 (-200 to 134) 105 (-132 to 345) 0.727 0.421 0.857 0.476 0.881 0.762 abdominal surgery with pneumoperitoneum and Trendelenburg positioning, the chest wall primarily distributes the increased airway pressure.23 This indicates that driving pressure may be inaccurate as a surrogate marker of lung strain when chest wall compliance changes.24 In this situation, direct assessment of transpulmonary pressure may be necessary to Driving pressure-guided individualised PEEP 40 * b * Plateau pressure (cm H2O) 30 25 20 * * T2 T3 Time T4 * * * 35 35 7 30 25 20 15 15 T1 T2 c * Driving pressure (cm H2O) * T3 Time T4 * * T1 T5 d T5 * 16 20 15 * PEEP (cm H2O) Peak inspiratory pressure (cm H2O) a - 12 * 8 10 T1 T2 T3 Time T4 T5 T1 T2 Individualised Standard T3 Time T4 T5 Fig 2. Intraoperative respiratory parameters recorded at the predefined five time-points; T1, 10 min after anaesthesia induction; T2, 30 min after implementation of pneumoperitoneum in the steep Trendelenburg position; T3, 1 h after T2; T4, 2 h after T2; and T5 just before emergence in the operating room. (a) Peak inspiratory pressure, (b) plateau pressure, (c) driving pressure, and (d) positive end-expiratory pressure. *P<0.0001. quantify the stress applied to the lung accurately. However, as measuring transpulmonary pressure using an oesophageal manometer may be invasive, the decision should be made based on a careful evaluation of the risks and benefits. Pneumoperitoneum with the steep Trendelenburg position enhances surgical conditions in some laparoscopic or robotic surgery. However, this approach causes the diaphragm to move upward. Consequently, airway pressure increases and chest wall compliance decreases.25 In our study, we found that both plateau pressure and driving pressure were relatively higher during pneumoperitoneum and the steep Trendelenburg position compared with previous open surgeries15,16 and laparoscopic or robotic surgeries.26,27 Previous research has shown a linear relationship between intraabdominal pressure (IAP) during pneumoperitoneum and respiratory driving pressure.28 The median IAP during pneumoperitoneum in the present study was relatively higher at 2 kPa compared with a previous multicentre study.29 Another study with an IAP of 2 kPa showed that when PEEP was set to 5 cm H2O or the IAPtargeted value, the median driving pressure reached as high as 12 and 17 cm H2O, respectively, despite surgeries being performed under a head-up tilt position.30 In summary, increased IAP during pneumoperitoneum and steep Trendelenburg position could potentially contribute to the higher plateau and driving pressures observed in this study. However, previous studies have shown that increased plateau pressure from elevated IAP does not always result in a proportional increase in transpulmonary pressure.27 Additionally, when chest wall compliance varies, driving pressure may not accurately reflect transpulmonary pressure.22 Therefore, relying 8 - Kim et al. Table 3 Comparisons of postoperative outcomes between the two groups. Data are mean (standard deviation), median (inter-quartile range), or n (%). CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; NA, not applicable; PACU, post-anaesthesia care unit; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation. *The percentage was calculated only in patients who developed postoperative complications. yMild respiratory failure was defined as PaO2 <8 kPa or SpO2 <90% at room air. Primary outcome (composite of postoperative pulmonary complications), n (%) Hypoxaemia Atelectasis Pleural effusion Pneumonia Requirements for rescue manoeuvres Count of postoperative pulmonary complications One complication, n (%)* Two or more complications, n (%)* PACU SaO2 at room air, % Mild respiratory failurey, n (%) Length of hospital stay, day ICU admission, n (%) Postoperative other complications, n (%) Cardiac complication Acute kidney injury Deep vein thrombosis Infection Wound dehiscence Anastomosis site leakage Ileus Postoperative bleeding Postoperative blood transfusion, n (%) Standard group Risk ratio or mean difference (n¼178) (n¼185) (95% CI) 25 (14.0) 36 (19.5) 0.72 (0.45e1.15) 0.215 4 (2.2) 16 (9.0) 2 (1.1) 0 (0.0) 6 (3.4) 7 (3.8) 29 (15.7) 1 (0.5) 1 (0.5) 10 (5.4) 0.59 (0.18e1.99) 0.57 (0.32e1.02) 2.08 (0.19e22.72) NA 0.62 (0.23e1.68) 0.584 0.076 0.973 >0.999 0.491 0.147 22 (88.0) 3 (12.0) 95.9 (2.7) 4 (2.2) 6.3 (4.1) 0 (0.0) 15 (8.4) 1 (0.6) 9 (5.1) 0 (0.0) 4 (2.3) 0 (0.0) 3 (1.7) 8 (4.5) 0 (0.0) 2 (1.1) 28 (77.8) 8 (22.2) 95.3 (2.8) 4 (2.2) 7.1 (7.1) 3 (1.6) 16 (8.6) 2 (1.1) 20 (10.8) 1 (0.5) 1 (0.5) 1 (0.5) 4 (2.2) 5 (2.7) 1 (0.5) 3 (1.6) 1.13 (0.90e1.42) 0.54 (0.16e1.84) 0.59 (-0.02 to 1.21) 1.04 (0.26e4.09) -0.81 (-2.00 to 0.38) NA 0.97 (0.50e1.91) 0.52 (0.05e5.68) 0.47 (0.22e1.00) NA 4.16 (0.47e36.84) NA 0.78 (0.18e3.43) 1.66 (0.55e4.99) NA 0.59 (0.12e4.10) solely on plateau pressure and driving pressure may not provide an accurate assessment of lung stress or strain in this surgical condition. PEEP plays a critical role as an essential component of modern intraoperative lung-protective ventilation.8 Previous studies have explored different methods for individualised a * b Pa2 (kPa) Pa2 (kPa) 6.5 6.0 5.5 P-value Individualised group c † 26 † 24 22 0.058 >0.999 0.181 0.260 >0.999 >0.999 0.068 >0.999 0.342 >0.999 >0.999 0.518 >0.999 >0.999 PEEP, including dynamic and static compliance, driving pressure, transpulmonary pressure, and electrical impedance tomography.21,24,31e33 Still, it is unclear which method is superior for clinical outcomes. Although recent meta-analyses found a reduction in PPCs with individualised PEEP,31,34 most of the included studies had small sample sizes. Furthermore, no Arterial oxygen saturation (%) Variables † † 20 18 † 99.5 † † † 99.0 98.5 98.0 5.0 T1 T2 T3 T4 T5 Time T1 T2 T3 T4 T5 Time Individualised T1 T2 T3 T4 T5 Time Standard Fig 3. Intraoperative arterial blood gas analysis at the predefined five time-points: T1, 10 min after anaesthesia induction; T2, 30 min after implementation of pneumoperitoneum in the steep Trendelenburg position; T3, 1 h after T2; T4, 2 h after T2; and T5 just before emergence in the operating room. (a) Arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide, (b) Arterial partial pressure of oxygen, and (c) Arterial oxygen saturation. *P¼0.045. yP<0.0001. Driving pressure-guided individualised PEEP strong evidence supports consistent improvement in patientimportant outcomes with individualised PEEP.31 Therefore, large-scale randomised controlled trials are needed to confirm the effects of individualised PEEP on relevant clinical outcomes in the future. Driving pressure is widely recognised as a surrogate parameter reflecting global lung strain.24 A robust association between driving pressure and survival was initially reported in patients with ARDS.35 Many studies supported the link between driving pressure and PPCs in surgical patients.8,36e39 However, the clinical effectiveness of modifying driving pressure as a therapeutic target remains inconclusive. Contrary to previous randomised controlled trials,14e16,26 a recent multicentre study in thoracic surgery found no benefit in driving pressure-guided ventilation.39 Similarly, a multinational trial involving obese patients showed no differences in PPCs despite lower driving pressure in the low PEEP group compared with the high PEEP group.11 In line with these findings, our study did not establish an association between driving pressure-guided PEEP and PPCs, although higher driving pressure was significantly associated with an increased risk of PPCs. Therefore, future studies should prioritise exploring the clinical utility of driving pressure-guided PEEP. A low level of PEEP can be tolerated by most surgical patients. However, PEEP can induce changes in cardiac output, leading to PEEP-induced haemodynamic deterioration in patients with comorbidities.40 A previous multicentred randomised study revealed that hypotension occurred more frequently in the group receiving higher PEEP than in those with lower PEEP.10 In the present study, most respiratory variables were kept within safe limits, and severe haemodynamic instability or impairment in mechanical ventilation did not occur in the individualised group. There was also no significant difference in TWA hypotension in the present study; however, the individualised group showed higher incidences of administration of vasoactive drugs and cumulative ephedrine doses. Therefore, monitoring whether PEEP-induced haemodynamic instability occurs closely is necessary when using individualised high PEEP. This study had several limitations. Firstly, because the study was conducted in a single tertiary teaching hospital, institutional policy and patient severity could have affected the results. Secondly, although we enrolled patients with a moderate or high risk of PPCs based on the ARISCAT risk score, the actual risk score was not as high as expected. As a result, our study was underpowered to detect a significant difference in the primary outcome. This could partly explain why most subjects who developed PPCs had minor complications. Thirdly, the intervention was manually performed for a relatively short time (40 s for recruitment and 30 s for the decremental PEEP trial). However, the intervention was conducted by two experienced researchers, and an independent investigator ensured the accuracy of the intervention in this study. Fourthly, in order to obtain a more precise estimate of the efficacy of driving pressure-guided PEEP, we opted for per protocol analysis. However, we acknowledge that this analysis could introduce biases and might not fully reflect realworld clinical practice, even the intention-to-treat analysis confirmed similar results. Lastly, there was no consensus regarding the strategy for driving pressure-guided ventilation. However, as a decremental PEEP trial may reduce shear stress by opening the alveoli even at low driving pressure,41 we adopted this method for PEEP titration. - 9 In summary, driving pressure-guided PEEP did not decrease PPC incidence within seven postoperative days in patients who underwent laparoscopic or robotic lower abdominal surgery. Although driving pressure-guided PEEP improved intraoperative lung mechanics and oxygenation profile, this benefit was not translated into postoperative clinical outcomes. Future multicentre studies are needed to confirm our results. Authors’ contributions Contributed to the conception and design of the study: H-KY, BRK Contributed to the acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data: H-KY, BRK, YJK, HWK, J-YJ, H-YC, J-HS, WHK, H-SK Contributed to drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content: H-KY, YJK, SH Contributed to revising of manuscript critically for important intellectual content: all authors Contributed to the final approval of the manuscript to be submitted: H-KY, YJK Agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: all authors Declaration of interest The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Appendix A. Supplementary data Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2023.08.007. References 1. Buia A, Stockhausen F, Hanisch E. Laparoscopic surgery: a qualified systematic review. World J Methodol 2015; 5: 238e54 2. Muaddi H, Hafid ME, Choi WJ, et al. Clinical outcomes of robotic surgery compared to conventional surgical approaches (laparoscopic or open): a systematic overview of reviews. Ann Surg 2021; 273: 467e73 3. Phong SVN, Koh LKD. Anaesthesia for robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy: considerations for laparoscopy in the Trendelenburg position. Anaesth Intensive Care 2007; 35: 281e5 4. Takahata O, Kunisawa T, Nagashima M, et al. Effect of age on pulmonary gas exchange during laparoscopy in the Trendelenburg lithotomy position. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2007; 51: 687e92 5. Huang D, Zhou S, Yu Z, Chen J, Xie H. Lung protective ventilation strategy to reduce postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) in patients undergoing robotassisted laparoscopic radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: a randomised double blinded clinical trial. J Clin Anesth 2021; 71, 110156 6. Canet J, Gallart L, Gomar C, et al. Prediction of postoperative pulmonary complications in a population-based surgical cohort. Anesthesiology 2010; 113: 1338e50 7. Fernandez-Bustamante A, Frendl G, Sprung J, et al. Postoperative pulmonary complications, early mortality, and 10 - Kim et al. hospital stay following noncardiothoracic surgery: a multicenter study by the Perioperative Research Network Investigators. JAMA Surg 2017; 152: 157e66 8. Ladha K, Vidal Melo MF, McLean DJ, et al. Intraoperative protective mechanical ventilation and risk of postoperative respiratory complications: hospital based registry study. BMJ 2015; 351: h3646 lez MA, Rodriguez9. Rossi A, Santos C, Roca J, Torres A, Fe Roisin R. Effects of PEEP on VA/Q mismatching in ventilated patients with chronic airflow obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994; 149: 1077e84 10. Hemmes SNT, Gama de Abreu M, Pelosi P, Schultz MJ. High versus low positive end-expiratory pressure during general anaesthesia for open abdominal surgery (PROVHILO trial): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014; 384: 495e503 11. Bluth T, Serpa Neto A, Schultz MJ, et al. Effect of intraoperative high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) with recruitment maneuvers vs low PEEP on postoperative pulmonary complications in obese patients: a randomised clinical trial. JAMA 2019; 321: 2292e305 12. Godet T, Cungi P-J, Futier E. Positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) in the operative theatre: what’s next? Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2019; 38: 435e7 13. Nestler C, Simon P, Petroff D, et al. Individualized positive end-expiratory pressure in obese patients during general anaesthesia: a randomized controlled clinical trial using electrical impedance tomography. Br J Anaesth 2017; 119: 1194e205 14. Park M, Ahn HJ, Kim JA, et al. Driving pressure during thoracic surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Anesthesiology 2019; 130: 385e93 15. Zhang C, Xu F, Li W, et al. Driving pressure-guided individualized positive end-expiratory pressure in abdominal surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg 2021; 133: 1197e205 16. Mini G, Ray BR, Anand RK, et al. Effect of driving pressureguided positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) titration on postoperative lung atelectasis in adult patients undergoing elective major abdominal surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Surgery 2021; 170: 277e83 17. Simon P, Girrbach F, Petroff D, et al. Individualized versus fixed positive end-expiratory pressure for intraoperative mechanical ventilation in obese patients: a secondary analysis. Anesthesiology 2021; 134: 887e900 18. Meininger D, Byhahn C, Mierdl S, Westphal K, Zwissler B. Positive end-expiratory pressure improves arterial oxygenation during prolonged pneumoperitoneum. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2005; 49: 778e83 19. Ferrando C, Soro M, Canet J, et al. Rationale and study design for an individualized perioperative open lung ventilatory strategy (iPROVE): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2015; 16: 193 20. Ferrando C, Soro M, Unzueta C, et al. Individualised perioperative open-lung approach versus standard protective ventilation in abdominal surgery (iPROVE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6: 193e203 21. Girrbach F, Petroff D, Schulz S, et al. Individualised positive end-expiratory pressure guided by electrical impedance tomography for robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a prospective, randomised controlled clinical trial. Br J Anaesth 2020; 125: 373e82 ~ o JC, Lessa MA, Motta-Ribeiro G, et al. Global and 22. Branda regional respiratory mechanics during robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery: a randomised study. Anesth Analg 2019; 129: 1564e73 23. Tharp WG, Murphy S, Breidenstein MW, et al. Body habitus and dynamic surgical conditions independently impair pulmonary mechanics during robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery: a cross-sectional study. Anesthesiology 2020; 133: 750e63 24. Williams EC, Motta-Ribeiro GC, Vidal Melo MF. Driving pressure and transpulmonary pressure: how do we guide safe mechanical ventilation? Anesthesiology 2019; 131: 155e63 25. Pelosi P, Quintel M, Malbrain ML. Effect of intra-abdominal pressure on respiratory mechanics. Acta Clin Belg 2007; 62(Suppl 1): 78e88 26. Xu Q, Guo X, Liu J, et al. Effects of dynamic individualized PEEP guided by driving pressure in laparoscopic surgery on postoperative atelectasis in elderly patients: a prospective randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol 2022; 22: 72 27. Shono A, Katayama N, Fujihara T, et al. Positive endexpiratory pressure and distribution of ventilation in pneumoperitoneum combined with steep Trendelenburg position. Anesthesiology 2020; 132: 476e90 28. Mazzinari G, Diaz-Cambronero O, Serpa Neto A, et al. Modeling intra-abdominal volume and respiratory driving pressure during pneumoperitoneum insufflation-a patient-level data meta-analysis. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2021; 130: 721e8 29. Queiroz VN, da Costa LGV, Takaoka F, et al. Ventilation and outcomes following robotic-assisted abdominal surgery: an international, multicentre observational study. Br J Anaesth 2021; 126: 533e43 30. Mazzinari G, Diaz-Cambronero O, Alonso-Inigo JM, et al. Intraabdominal pressure targeted positive end-expiratory pressure during laparoscopic surgery: an open-label, nonrandomized, crossover, clinical trial. Anesthesiology 2020; 132: 667e77 31. Zorrilla-Vaca A, Grant MC, Urman RD, Frendl G. Individualised positive end-expiratory pressure in abdominal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2022; 129: 815e25 32. Eichler L, Truskowska K, Dupree A, Busch P, Goetz AE, € llner C. Intraoperative ventilation of morbidly obese Zo patients guided by transpulmonary pressure. Obes Surg 2018; 28: 122e9 33. Fernandez-Bustamante A, Sprung J, Parker RA, et al. Individualized peep to optimise respiratory mechanics during abdominal surgery: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Br J Anaesth 2020; 125: 383e92 34. Zhou L, Li H, Li M, Liu L. Individualized positive end-expiratory pressure guided by respiratory mechanics during anesthesia for the prevention of postoperative pulmonary complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Monit Comput 2023; 37: 365e77 35. Amato MBP, Meade MO, Slutsky AS, et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 747e55 36. Neto AS, Hemmes SNT, Barbas CSV, et al. Association between driving pressure and development of postoperative pulmonary complications in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation for general anaesthesia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4: 272e80 Driving pressure-guided individualised PEEP 37. Mathis MR, Duggal NM, Likosky DS, et al. Intraoperative mechanical ventilation and postoperative pulmonary complications after cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 2019; 131: 1046e62 38. Mazzinari G, Serpa Neto A, Hemmes SNT, et al. The association of intraoperative driving pressure with postoperative pulmonary complications in open versus closed abdominal surgery patients - a posthoc propensity scoreweighted cohort analysis of the LAS VEGAS study. BMC Anesthesiol 2021; 21: 84 - 11 39. Park M, Yoon S, Nam J-S, et al. Driving pressure-guided ventilation and postoperative pulmonary complications in thoracic surgery: a multicentre randomised clinical trial. Br J Anaesth 2023; 130: e106e18 40. Luecke T, Pelosi P. Clinical review: positive end-expiratory pressure and cardiac output. Crit Care 2005; 9: 607e21 41. Cereda M, Xin Y, Emami K, et al. Positive end-expiratory pressure increments during anesthesia in normal lung result in hysteresis and greater numbers of smaller aerated airspaces. Anesthesiology 2013; 119: 1402e9 Handling Editor: Gareth Ackland