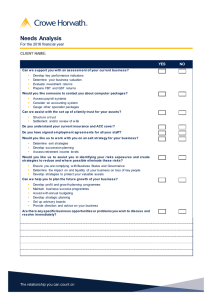

JO Y U M B E R 29 S P H T F L A N R U S P R I N G , 1979 ISSN 0021-8235 F undam entally the W a ld o rf School does not w ant to educate but to awaken. It does not aim at being a system o f principles. It aim s at being life — not science, not cleverness, but art; vital action; aw akening deed. R u d o lf Steiner Jo u rn al for A nthroposophy, N um ber 29, Spring, 1979 © 1979, T h e A nthroposophical Society of A m erica, Inc. E D U C A T IO N A Special Issue For the Fiftieth Anniversary o f W ald o rf E ducation in N orth Am erica CONTENTS ARTICLES A la n H oward 3 Early Childhood D estruction and New S tart of the O riginal W aldorf School Education for Adolescents Inform ation — or Knowledge as Experience? M. C. R ichards 10 A l L aney R u d o lf Steiner 26 34 T o Have, T o Be and T o Become A bout G oetheanistic Science Karl Ege H ans Gebert 40 44 Christy Barnes Lisa M onges 55 66 Bum ble-Baby, a poem T h e Beetle and the Spider, a fa b le Christy Barnes M artin K urkow ski 9 18 T o E ducate Youth, a poem A C hild’s Evening Prayer, a poem L ittle Myths R u d o lf Steiner A lb ert Steffen 19 25 M ark T aper H einz F rankfurt 54 79 L iterature an d the D ram a of Polarities at P uberty A S tudent’s Memories of R udolf Steiner POEMS AND PROSE Stars, an assignment Cure, an anecdote ILL U STR A TIO N S AND SONGS M ichael and the D ragon, a ch ild ’s crayon drawing Little Lam b, by Blake 2 20 T h e Shepherd, by Blake songs com posed by Laura Taylor T h e Light of Sun, by R udolf Steiner com posed by H arry Kretz M other and Child, a drawing D onald H all 22 23 24 REVIEW S E ducating as an A rt, E dited by Ekkehard Piening and Nick Lyons M. C. R ichards Teaching as a Lively A rt, M arjorie Spock Erika V. A sten Pilgrimage to the Tree o f L ife, A lbert Steffen Jea n n e Bergen 77 80 82 The Living Earth, W alther Cloos 84 Contributors to this Issue R a lp h B rockelbank 88 1 in]M age:colrdw Im [ ichael an d the D ragon 2 C h ild ’s Crayon Drawing Information -or Knowledge as Experience? ALAN HOW ARD T h e business of education is knowledge; a n d it should follow th a t the business of the teacher is knowing w hat knowledge is. T h a t is not quite so stupid as it sounds; a n d a little enquiry into the n atu re of knowledge an d knowing cannot come amiss in w hat we are discussing here. Usually we are satisfied if the teacher knows — th a t is to say, has knowledge of — this and th at. Q uite often the m ore a teacher knows, the m ore courses he has taken, the m ore letters he has behind his n am e — the m ore we are im pressed by him . He m ust, as a result, have so m u ch m ore to pass on to the children; a n d so this idea of knowledge as a quantity, som ething th a t can be passed on or stored up, persists even in the best educational circles. Knowledge, however, is an experience, not a quantity, a transform ation of the knower th rough the experience of know ­ ing. O f course he retains a m em ory of the experience, which can be described, b u t w hich bears the sam e relation to the ex­ perience itself as a p h o to g rap h does to the experience of look­ ing at the sam e scene w ith one’s own eyes. T h a t rem em bered an d com m unicated im age is inform ation. It can be w ritten up in books, a n d o th er people can read a n d even reproduce it; b u t it is not necessarily their knowledge. A nd having m ade this distinction, we have no intention, in so doing, of underestim ating the value of inform ation. T h a t w ould be nonsensical; b u t the distinction is necessary in discussing knowledge in relation to education, where both knowledge and inform ation by this definition play a n im p o rta n t p a rt. 3 T he Teacher So m u ch o f the knowledge we deal w ith in schools is of necessity o ther people’s knowledge, secondhand experience, our inform ation. W e get it out of books; a n d the teacher is one who today gets alm ost all his know ledge o ut of books. T h e day m ay come when a m ore enlightened — and m ore generous — society will discover th a t one of the finest investm ents it can m ake is in the fullest possible tra in in g of its teachers. They will be very carefully selected of course; b u t once th a t is done, th en they will be sent ro u n d th e w orld into all kinds of situ a ­ tions, doing various kinds of jobs, m eeting all kinds of people, before they are allowed to stan d before a g roup of children. W h at they com m unicate then by way of knowledge m ay at least be lit up again a n d again w ith the w ealth of their p e r­ sonal experience. T eachers are far too young, too exclusively book-fed when they begin to teach, especially teachers of the youngest children. T hey know so little ab o u t life a n d the world. O ne of the advantages of our independence as W ald o rf schools is th a t we are n ot b o u n d to choose ou r teachers only according to academ ic qualifications. T h a t m ust be there, of course; b u t w hat they are as h u m an beings, w hat their life ex­ perience has been, is for us equally im p o rtan t. Everything else being equal, even if a prospective teacher h a d no professional qualifications a n d we were convinced th a t he was just the m an for this or th a t g roup o f children, o u r independence gives us the o p p o rtu n ity to ap p o in t him . R udolf Steiner h a d som ething to say on this, too, p articularly a b o u t class-teachers. A fter eight years w ith a class, they should have a year’s sabbatical; not as a holiday, however, b u t as a n o p p ortunity for getting some entirely different experience. O f course there is a lim it to this. T eachers w ould still have to get m u ch out of books; b u t they w ould be far m ore effective a n d h u m an as teachers if they were also people of wide experience. Anyone who has ever talked to children knows w hat a difference it m akes in regard to this or th a t m a tte r if one can p u n c tu a te it now a n d th en w ith, “Now, w hen I was in . . . ” or, “W hen I was a. . . . ” 4 Everything im m ediately comes alive; the children “sit u p and take n o tice.” Info rm a tio n and A udio-V isual A ids U ntil such tim es, however, we m ust still d epend largely on w hat we acquire from books; and th a t m akes it all the m ore im p o rta n t to appreciate this distinction betw een knowledge a n d inform ation, so th a t the ch ild ren ’s know ing can be real living experience for them . Otherwise, just because the bulk of ou r knowledge is other people’s experience gleaned out of books, it can becom e lifeless a n d dull, an d we have to enliven (sic) it w ith all kinds o f audio-visual aids, an d any o th er of the p a ra p h e rn alia an enterprising educational supplier can think up. If ou r conception of the teacher is largely a “passer-on” of inform ation, he will not only depend m ore and m ore on these things, b u t they will in tim e replace him . H e will be reduced to the status of the Greek pedagogue, who was not the Greek equivalent of a teacher, although we som etim es use this highsounding word for “tea c h e r” or “e d u c a to r.” He was a slave, who carried the child’s m aterials to and from school and w aited for him till the p ro p er teachers h ad finished with him! W hen the teacher begins to open up the various avenues of knowledge, even p rin te d tex tb o o k s, charts, m odels an d diagram s are kept to the very basic m inim um — except of course for general reading m aterial w hich the children are e n ­ couraged to use in their own tim e. As to all the elaborate a n d ingenious ap p aratu s for teaching u n d e r the n am e of a u d io ­ visual aids, it w ould be extrem ely rare for a W ald o rf teacher to use any of it before the high school. A nd such a statem ent really shocks m any people today. “But these are w onderful aids to tea c h in g ,” they declare. “D on’t you realise how m u ch m ore accurately, efficiently a n d beautifully they brin g the world to the children? You really have no right to deny the children these th in g s.” W e realise it all right; b u t we realise too m any o ther things in the whole educational set-up. As to denying children these 5 wonders, we can only categorically reto rt th a t we are “denying” them nothing. O n the contrary, we are quite con­ sciously an d deliberately giving them a m uch needed rest from it all, w hich is ab o u t the m ost a school can do. O u r m odern w orld is such th a t it is no longer a m a tte r of having these things to use w hen we really need them . W e cannot escape from them ; a n d children no less th an adults are continually bo m b ard ed by the bew ildering flicker of m achine-m ade images an d the cacophony of artificial sound which engulf them from m orning to night. W h at dam age this m ay be doing to them physically has yet to be fully established; w hat dam age it is doing to the possibilities o f joy a n d fellowship in learning and doing things together is all too a p p a re n t. Know ledge as E xperience In the W ald o rf school we have a hom e-room teacher for each grade, who starts a t G rade O ne, a n d unless som ething unavoidable intervenes, goes w ith th a t sam e grade th ro u g h the seven others up to G rade Eight. H e or she is not w ith th at group of children all day, every day; b u t none the less they are his — or her — children for those eight years. W e also begin every m o rning in all grades w ith w hat we call the M ain Lesson, w hich lasts for approxim ately two hours. D uring this lesson the basic skills are tau g h t a n d practised; a n d a p ro ­ gressive in tro d u ctio n to the different fields of knowledge is m ade. T h e hom e-room teacher — or class-teacher as we call him — is w ith his class every day a t th a t tim e as it goes th ro u g h the eight grades. His job is to unfold the story of M an in a personal, living knowledge experience, a n d because he has eight years in which to do it, he gets to know his p a rticu la r children — a n d they him — alm ost as well as a p a re n t knows his fam ily. T hey work in close co ntact w ith one an o th er in every way all along the line. R eal h u m a n relationships are cultivated a n d assured; a n d the teacher an d children retain , as well as their experience in knowledge, an experience of h u m an living together w here joys a n d sorrows, problem s an d discoveries, the whole g a m u t of h u m a n experience, has been lived th ro u g h intim ately. 6 But this isn’t all th a t this arran g em en t prom otes; for while the teacher is w orking in this way with his class, w ith little m ore equipm ent, as has been explained, th a n his own knowledge and skills have given him , inner activity in the fullness of knowing is developed in the children to the greatest capacity. T h e teacher brings all his power of language, d ram a, gesture, tone an d any special artistic skill he m ay possess to m ake w hat he has to share w ith them a direct, living ex­ perience. T he child as a result becomes fully involved in feel­ ing and will as well as in thinking. He is not just a recipient of the lesson b u t a co-creator of it. T h e feeling a n d will are of course m ore active, for thinking as we u n d erstan d it — which as such will come m ore into its own in the high school — is at this stage m ore of a picture-form ing quality. B ut it is thinking; thinking in a state of grow th, which will becom e the logical thinking an d ju d g m e n t u p o n w hich the intellect will later rely. It will be all the m ore vigorous a n d lively because of the way it has been exercised in its earlier stages. For the point is th a t w hat the class-teacher seeks to prom ote is activity as against passive reception, creativity as against m ere rep ro d u c ­ tion, original im agination as against m ere observation. T his we believe only the teacher as a full h u m an being can do. A nd as the whole being of the child is b rought into inner m ovem ent, all this finds vivid, colorful an d d ram atic expression w hen the child writes, draws, paints, m odels an d acts w hat he has been involved in, in this teacher-pupil experience. Those creations are his text-books; those activities are his audio-visual aids; each child is dealing w ith the sam e experience, b u t each p ro ­ duces an original expression of it. T h e work of W ald o rf children is brig h t w ith color, com pel­ ling w ith originality, because the intellect, w hich tends to absorb a n d reproduce, is not too early pressed into service before the experience of knowledge has h a d a chance to stim ulate h e a rt an d h an d . Love a n d enthusiasm pulsate th rough w hat the intellect is certainly dealing w ith also, b u t as a p a rtn e r, not as the d om inating influence. T h e teacher is not just an instructor, and certainly not a technician. H e is one of the child’s earliest and m ost im p o rta n t contacts w ith hum anity outside the hom e; an d knowledge is not just an abstract q u a n ­ 7 tity to be acquired, b u t the m edium th ro u g h which th a t c o n ­ tact is nourished. Knowledge is living h u m an experience; a n d just because so m uch o f w hat we call knowledge is this mass of inform ation in books, the teacher, particu larly of grade school children, has to be able to transform it — naturally, w ithout tam pering w ith its factu al content — so th a t it first becom es his experience. Only thus will he be able to work on th a t im aginative, re ­ creative faculty of the child w hich is the child’s experience. O therw ise, learning becomes alm ost entirely a m em orizing skill, to which the child has to be coerced or induced by some external rew ard — a rew ard which has n othing to do with the acquisition o f know ledge as such. T here are no such inducem ents in a W aldorf school; no m arks, grades, certificates, prizes, a n d especially is there no use m ad e of th a t p articularly pernicious inducem ent of com ­ petition in learning am ong the children. C hildren are n a tu ra l­ ly aw are th a t this one is b e tte r th an an o th er at this or that; an d this is often m ad e the subject of conversations on the divi­ sion of h u m an gifts; b u t it is never artificially exploited to set one child above or below another. E ducation, Steiner insisted, is an art; an d the teacher m ust all the tim e strive to be an artist. N othing pretentious was m ean t by th at; a n d it certainly has no th in g to do w ith the in tro d u ctio n of arty-crafty gim m icks into teaching. T o be an artist as teacher m eans simply to be able to re-create w hat is not the p ro d u ct of one’s own experience, an d m ake it one’s own. W hen an accom plished pianist gives a perform ance of Beethoven he certainly has to play w hat Beethoven, not he, wrote; b u t he is an artist to the degree th a t he can re-create w hat Beethoven w rote a n d m ake his perform ance of it his own. T h e teacher has to m ake th a t otherwise abstract thing called knowledge into a personal affair. H e has to try and know it as if he were know ing it directly a n d at firsth an d for the first tim e. R udolf Steiner often p u t one or an o th er teacher of the first W ald o rf school into a tem porary panic by telling him to teach a c ertain subject which was com pletely outside 8 his field. Those lessons were invariably some of the most successful! It is for this reason th a t the teacher should plunge deeply into w hat is at work in the experience o f knowing; for this knowing activity is far m ore th a n an intellectual operation. T h e ability to know is w hat m akes m an m an; it is w hat distinguishes him from all o ther creatures. M an is fu n d a ­ m entally a K nower. “M an feels th rough know ledge,” says Em erson, “the privilege to be"', a n d it is this identity of know ­ ing a n d being w hich is falling a p a rt in o u r tim e. W e all suffer to a certain extent from schizophrenia of intellect a n d being. E ducation has the responsibility of reuniting them , an d lifting knowledge out of the intellectual process of inform ing into a sharing of life experience. Bumble-Baby My baby’s like a bum blebee, So ro u n d a n d good w ith fuzzy head A nd tiny legs all tucked in bed, A nd she sleeps so busily! In her dream s, w ith cozy love, She hum s an d hovers just above H er little body th ro u g h the sunny Fields she roam ed before her birth; Sucks a n d harvests heaven’s honey, H oards it hom e for hives on earth . W hen she wakes, she looks up th rough Eyes like pansy-petal dew; H er cheeks a n d b re a th are flowers’ too. Tell m e, baby, w hat are you? A tiny blossom -bundle, maybe? A bee-flower? O r a bum ble-baby! Christy Barnes 9 Early Childhood* M. C. RICHARDS T he education o f the child fo llow s seven-year rhythm s, which are based on R u d o lf Stein er’s observations o f childhood developm ent. H e explains this fo u n d a tio n on which education should be based in a sm all book called T h e E ducation of the Child. It was prepared f o r pub lica tio n in 1909 after he had given the m aterial in lectures in various places. It seem s a good place to start to exam ine what stands behind W a ld o rf schools. I shall a tte m p t here to steer a course through som e parts o f the content o f the book w hich deal especially with early childhood. T he quotations fr o m Steiner used in what follow s are all taken fr o m the above-m entioned book. W hen I first began to rea d Steiner on education, I was at a tim e in m y life w hen I h a d h a d enough of high hopes a n d e n ­ thusiasm as a basis for education, an d enough reaction against som ething. In 1962 I wrote: I w ant to know why a child is sent to school a t all. W hy a t one age ra th e r th a n another. W hy he is ta u g h t one subject now a n d a n o th e r late r on. A n d I d o n ’t w ant to be told th a t it is to keep up w ith the enem y or th a t it is legally req u ired or th a t it’s w hat an expert recom m ends. I w ant to know how it gets th a t way, in th e enem y’s or the law ’s or ex p e rt’s m ind. I am not satisfied w ith opportunism or exp eri­ m ent as a ratio n ale o f curriculum . I w ant to know w hat needs (whose needs) are being served by doing things one way ra th e r th a n an other, a n d w hat m akes *This article is draw n from the m anuscript of the book, W holeness in L iv ­ ing and Learning or Steps Toward a N ew Culture by M. C. R ichards. 10 anybody th ink so. I w ant to know w hat happens to the artist who lives n atu rally in a child’s respon­ siveness to rhythm a n d tone an d color and story, w hat happens to the child in m an . I w ant to know why so m any grow n-ups who are sm art in school blow their brains out in m iddle age, or rely on anxiety depressants. I w ant the whole story from beginning to end. T h e re are answers to these questions. (C entering, W esleyan University Press, 1964.) W e d o n ’t know all the answers, not even Steiner knew all the answers, b u t he looked for them in ways which diverge from the m aterialism of our colleges o f education or from the piety of parochial schools. It is w orth looking into. Steiner speaks of the “three births of the h u m a n b e in g .” T h e first one is the b irth of the physical body, w hich we think of as the b irth of the child. T h e second is the b irth of the etheric body* at the change of teeth. T h e th ird is the b irth of the astral body** at puberty. H e says: It m ust not be im agined th a t these develop uniform ly in the h u m a n being, so th a t at any given point in his life — the m om ent of b irth , for exam ple — they are all equally developed. T his is not the case; their developm ent takes place differently in the different ages o f m a n ’s life. T h e right fou n d atio n for education, a n d for teaching also, consists in a knowledge of these laws of the developm ent of h u m an n atu re. D uring the first seven years (approxim ately) of the child’s life, the physical body is form ing its organs. It is the physical e n ­ vironm ent w hich is o f crucial im portance at this period. N ot only the environm ent of shapes a n d colors an d so forth, b u t the environm ent o f behavior. T h e child drinks everything in. Its inner being im itates its surroundings. T h e power of ex am ­ ple teaches. *The bearer of living form ative forces in plant, anim al and m an. **The bearer of sentient consciousness in m an and anim al. 11 T h e kind of toys a n d gam es are best w hich allow for fantasy a n d im agination. “T h e work of the im agination m olds an d builds the form s o f th e b rain . T h e b ra in unfolds as the muscles of the h a n d unfold w hen they do work for w hich they are fitted. Give the child th e so-called ‘p retty ’ doll, a n d the b rain has n othing m ore to do. Instead o f unfolding, it becom es stunted an d dried u p .” B etter, he says, to “m ake a doll for a child by folding u p an old napkin, m aking two co r­ ners into legs, th e o th er two corners into arm s, a knot for the head, a n d p a in tin g eyes, nose an d m o u th w ith blots of in k .” He recom m ends toys an d picture books w ith m ovable figures. T h e colors w hich su rro u n d the child should be selected w ith awareness th a t it is the com plim entary color which is created w ithin the child a n d which will influence him . A n excitable child should be dressed in red; he will inw ardly create the o p ­ posite, green; a n d this activity o f creating green has a calm ing effect. Pleasure an d delight, Steiner says, are the forces w hich most rightly quicken a n d call fo rth the physical form s of the organs. A t the sam e tim e he speaks of bringing the child “into a right relationship, physically” w ith things like food. T eachers who have a happy look a n d m an n er, a n honest unaffected love, will fill the physical environm ent w ith w arm th. W a rm th “m ay literally be said to ‘h a tc h o u t’ the form s of the physical o rg an s.” T h e value o f ch ild ren ’s songs is stressed. T h e ir rhythm an d beauty of sound are m ore im p o rta n t th a n their m eaning. Also the wish of the child to p a in t a n d to scribble w ritten signs an d letters long before he understands them should be understood as a deep will to im itate. D ancing m ovem ents in m usical rhythm have a pow erful influence in building up the physical organs. A nd w hen the child comes to k in dergarten, he tends to im itate w hat is alive in the atm osphere. I have noticed in the schools I have observed th a t there is a m ark ed sense of form in beginning the day an d in ending it. W ith the tiny children, it is often sitting in a circle, lighting a candle, holding hands, saying a verse, singing songs, acting out a story. A fter the circle, there is play tim e a n d w atercolor pain tin g . T h e n snacks. T h e n ou td o o r play. M aybe a walk o r 12 work in the garden. O r a p u p p et show on a rainy day. T h en lunch and n ap . A nd a final circle after playtim e. In a th ird grade class which I visited recently, th e young m an teacher stood at the door at the end of the day and shook each child’s h an d , said goodbye to him or her by nam e, an d the child as well clasped the h an d , said farewell. “G ood­ bye Neil, Goodbye M r. Levin. Goodbye Amy, Goodbye M r. Levin. Goodbye M atthew , Goodbye M r. L evin.” A m o m en t’s pause in the doorway. A contact, a greeting, an affirm ation of identity and affectionate respect; an acknow ledgem ent of m eaningful tim e spent together. I was touched by it. A nd it seem ed to be felt a n d m ean t by the children as well as by Paul Levin. N ot staged no r artificial. It bespoke th a t special kind of dignity th a t children have, even with all their pettiness and disorder a n d falsity. E ducation of the elem entary school years is based not on in ­ tellect b u t on im agination a n d inner picturing, “ . . . i t is not abstract ideas th a t have an influence on the developing etheric body, b u t living pictures th a t are seen and com prehended in ­ w ardly.” T h e ch ild ’s m em ory, w hich is connected w ith the etheric body, is of course present, b u t not yet ready for ex­ ternal stim ulation. It is sim ply to be nourished b u t not developed by external m easures d u ring this period. It will then unfold freely and of its own accord. Likewise the powers of thought a n d jud g m en t w hich will w aken consciously at p u b e r­ ty, m ust be allowed to unfold w ithout pressure d u rin g these early years. W ith the change of teeth, when the etheric body lays aside its o uter etheric envelope, there begins the tim e when the etheric body can be worked upon from w ithout. T h e form ation a n d grow th of the etheric body m eans the m olding and developing of the in ­ clinations an d habits, of the conscience, the character, the m em ory a n d tem peram ent. T h e etheric body is worked upon by pictures a n d e x ­ am ples — i.e. by carefully guiding the im agination of the child. As before the age of seven we have to give the child the actual physical p a tte rn for him to copy, 13 so betw een the tim e of th e change of teeth an d puberty, we m ust b rin g into his environm ent things w ith the right in n er m ean in g a n d value. For it is from the inner m eaning an d value of things th a t the grow ing child will now take guidance. W hatever is fra u g h t w ith a deep m ean in g th a t works th ro u g h p ic­ tures a n d allegories is the rig h t th in g for these years. T h e etheric body will u n fo ld its forces if th e wellordered im agination is allowed to take guidance from the in n er m eaning it discovers for itself in pictures a n d allegories — w hether seen in real life or com ­ m u n icated to the m ind. It is not ab stract conceptions th a t work in the rig h t way on the grow ing etheric body, b u t ra th e r w hat is seen and perceived — not indeed w ith the ou tw ard senses, b u t w ith the eye of the m ind. T his seeing a n d perceiving is the rig h t m eans of ed u catio n for these years. It is u p o n this g ro u n d o f im agination th a t the later powers of intellect a n d ju d g m e n t a n d critical thinking will be based. T hey will be rooted in feeling a n d im agination. A nother characteristic of children of these years, which Steiner spells out a n d stresses as essential is the wish o f the children to love an d respect their teachers. “V eneration and reverence are forces w hereby th e etheric body grows in the right way.. . . W here reverence is lacking, the living forces of the etheric body are stu n ted in th eir g ro w th .” Steiner em phasizes th e need to develop m em ory in the elem entary school years an d answers th e arg u m en t against m em orizing things we d o n ’t as children quite u n d erstan d . He says th a t “o th er forces of the soul are a t least as necessary as the intellect if we are to gain a com prehension of things. It is no m ere figure of speech to say th a t m an can u n d e rsta n d with his feelings, his sentim ent, his inner disposition, as well as with his in te lle c t.” H e says th a t real intellectual u n d erstan d in g comes after puberty. C hildhood is the tim e to store m em ory w ith cu ltu ral riches, w hich late r can becom e concepts a n d su b ­ jected to ind ep en d en t ju d g m e n t a n d criticism . Steiner quotes a 14 m ost interesting passage from a book on education by Jean Paul (L evena or Science o f E ducation) supporting this view: Have no fear of going beyond the childish u n d e r­ standing, even in whole sentences. Your expression an d th e tone of your voice, aided by the child’s in ­ tuitive eagerness to un d erstan d , will light up h a lf the m eaning, an d w ith it in the course of tim e the other half. It is w ith children as w ith the Chinese a n d p eo ­ ple of refinem ent; the tone is h alf the language. . . . W e are far too prone to credit th e teacher with everything the children learn. W e should rem em ber th a t the child we have to educate bears h a lf his world w ithin him all there and ready tau g h t, nam ely the spiritual half, including, for exam ple, the m oral and m etaphysical ideas. For this very reason language, eq u ip p ed as it is w ith m aterial images alone, cannot give the spiritual archetypes; all it can do is to illum ine them . Jean Paul goes on to praise the gifts children have for invent­ ing words. T h e curriculum develops out of correlations betw een the physical developm ent of the grow ing child an d his inner developm ent. T h e form of our body develops gradually. T o follow its changes is a study in itself. Likewise the inner form s of ou r b e ­ ing gradually unfold; an d the thresholds of bodily changes are also the thresholds of inner developm ent. W hen one can view the n a tu re of m an, not despis­ ing w hat is physical a n d bodily, one can do a great deal for the ch ild ren ’s h ealth as a teacher or educator. It m ust be a fu n d am en tal principle th a t spirituality is false the m om ent it leads away from the m aterial to some castle in the clouds. If one has come to despising the body, an d to saying: O h, the body is a low thing; it m ust be suppressed, flouted, one will m ost certainly not acquire the pow er to 15 educate m en soundly. For, you see, you m ay leave the physical body out of account, an d perhaps can a tta in to a high state of abstraction in your spiritual n a tu re , b u t it will be like a balloon in the air, flying off. A spirituality not related to w hat is physical in life can give n othing to social evolution on the earth; an d before one can wing one’s way into the heavens, one m ust be p rep a re d for the heavens. T his p re p a ra ­ tion has to take place on earth.* In conform ity w ith the inner developm ent of the child, history begins with the fairy tale, legend, bible story and m yth, th en goes on to biography, a n d then w ritten history. T h e historic consciousness of the child follows in its develop­ m ent the evolution of h u m an consciousness. T h e seventh graders are learning about revolutions at just the tim e when they are beginning to feel in themselves a creative change tow ard the independence of an ad ult, feeling as their bodies begin to change, the tran sfo rm atio n of d ream in g child into waking youth. In an o th er connection, too, the presentation of liv­ ing pictures to the m ind is im p o rta n t for the period betw een the change of teeth and puberty. It is essen­ tial th a t the secrets of N ature, the laws of life, be tau g h t to the boy or girl not in dry, intellectual c o n ­ cepts. Parables of the spiritual connections of things should be b rought before the soul of the child in such a m a n n e r th a t b eh in d the parables he divines an d feels, ra th e r th a n grasps intellectually, the underlying law in all existence. 'A ll th a t is passing is b u t a p a ra b le ’ m ust be the m axim guiding all our education in this period. It is of vast im portance for the child th a t he should receive the secrets of N atu re in parables before they are bro u g h t before his soul in the form of ‘n a tu ra l laws’ an d the like. A n exam ple m ay serve to m ake this clear. Let us im agine th a t we w ant to tell a child of the im m ortality of the soul, of *The Spiritual G round o f Education by R udolf Steiner, pp. 110-111. 16 the com ing forth of the soul from the body. T h e way to do this is to use a com parison, such, for exam ple, as the com parison of the butterfly com ing forth from the chrysalis. As the butterfly soars up from the chrysalis, so after d e a th the soul of m an from the house of the body. No m an will rightly grasp the fact in intellectual concepts, who has not first received it in such a picture. By such a p arable, we speak not m erely to the intellect b u t to the feeling of the child, to his soul. A child who has experienced this will a p ­ proach the subject w ith an altogether different m ood of soul when late r it is ta u g h t him in the form of in ­ tellectual concepts. It is indeed a very serious m atte r for any m an if he was not first enabled to ap p ro ach the problem s of existence w ith his feeling. T hus it is essential th a t the ed u cato r have a t his disposal parables for all the laws of N a tu re a n d secrets of the w orld. In the tra in in g program s for W ald o rf teachers, the a rt of creating such parables is em phasized. It is an a rt th a t m ust be practiced with total sincerity an d w ithout condescension. “For w hen one speaks in p arab le an d picture, it is not only w hat is spoken an d shown th a t works upon the h earer, b u t a fine spiritual stream passes from one to the other, from him who gives to him who receives. If he who tells has not him self the w arm feeling of belief in his parab le, he will m ake no im pres­ sion on the other. For real effectiveness, it is essential to believe in one’s parables as in absolute realities. A nd this can only be when o n e’s th o u g h t is alive w ith spiritual knowledge. Life flows freely, u n h in d ered , back a n d fo rth from teacher to p u p il.” Steiner says the teacher does not need to try to “think u p ” parables. T hey are the reality he sees w hen his eyes are opened th ro u g h anthroposophy. T h e pictures are “laid by the forces of the w orld w ithin the things themselves in the very act of their creation.. . . T h a t such a th in g as a seed has m ore w ithin it th a n can be perceived by the senses, this the child m ust grasp in a living way w ith his feeling a n d im agination. He m ust, in 17 feeling, divine the secrets of existence.” T he sensory world is the doorway to the spirit. * In all these ways and m ore, knowledge is m ade an inner ex ­ perience. T h e child feels the connection betw een him self and the seasons and the anim als, plants, rocks, the starry skies, m o u n ta in s a n d rivers, bridges a n d skyscrapers. T h e m aterialist’s way of thought, Steiner says, will never give rise to a really practical a rt of education. N arrow ing reality to only one of its elem ents, it creates a basic m istrust, illness, and, I w ould add, crim inality. Evil, there is reason to believe, comes ab o u t w hen the h u m an being is estranged from the depths of his own n a tu re . These depths can be continually spoken to th rough p arable, allegory, story, m yth. They are stories th at connect the h u m an soul a n d life of feeling with external events. O ur lives are such stories, m oving like m usic, on m ore th a n one level at once. The Beetle and the Spider A beetle, w hich h a d just craw led out of its p u p a, strolled th ro u g h a m eadow betw een the blades of grass an d huge flowers an d gazed a t the new sights. “G reat guns, how the w orld has changed since I last saw it! T h e sun is m u ch b righter, the leaves and grass are m uch m ore delicate. How colorful the w orld has become! T h e trails also are m uch better, a n d w alking is so easy. Everything was so dull before. How could such a change have come about?” T h e beetle w andered aro u n d a n d asked its fellow creatures ab o u t this, one after the other. Finally the glistening, bluegreen beetle m et a very old spider, who h a d seen m uch of the w orld, a n d she answered: “You say th a t the world was different — dull a n d colorless — w hen you were a grub. Look at yourself! T his will give you the clue.” — M artin Kurkowski, 12th grade 18 TWO VERSES B Y RUDOLF STEINER T o educate youth Is to foster an d tend: In m atte r — the spirit, In today — the tom orrow , In earthly life — T h e spirit’s existence. Translation by M agda M aier & Tilde von A Child’s Evening Prayer From my head to my feet I’m the picture of God. From my h eart into my hands I feel G od’s living breath . W hen I speak w ith my m outh I follow G od’s own will. W hen I gaze on God In the whole world-all, In fath er and m other, In all dear people, In beast an d flower, In tree an d stone, No fear can come near, Only love For all th a t’s aro u n d m e here. Translation by Arvia Ege 19 Songs fo r Children These songs have been sung f o r som e years by children at the R u d o lf Steiner School in N ew York. T he B lake songs were com posed by the wife o f a B ritish playw right o f the last cen­ tury a n d given to Steele M acK aye, the fir s t A m erica n to act H am let in England. T hey are pu b lish ed here f o r the fir s t tim e. “T he L ig h t o f S u n ” is a verse fr o m R u d o lf S tein er’s First M ystery D ram a. W hile he was a class teacher, H arry K retz com posed the m usic a n d it becam e the school song. L i t t le L a m b by W il lia m B la k e m u s i c c o m p o s e d by L a u r a T a y lo r nem dsath[olcrui]p-gI: 20 ]21 sicop -ltru d n age:h [Im How neitm dlsa]p-hg[ocIr:u 22 S weet is the Shepherd’s S weet Lot by W i l l i a m B l a k e m usic byLa u r a T a y lo r The L ight of S u n neitm dlsa]p-hg[ocIr:u b y R u d o l f S t e i n e r m usic by H a r r y K retz 23 M other a[Im hitrpouf]n d Child age:blck-ndw 24 D onald H all TWO LITTLE MYTHS — Albert Steffen School Visit W hile, at a teaparty, they were telling about the deeds of a truly good and wise m an, a little girl w ith delighted eyes said suddenly th a t she h ad d ream ed about him . He had come into her school a n d h a d spit in all directions — w hereupon every kind of toy h a d appeared: jum ping-jacks, lead soldiers, p u p ­ pets th a t p u t on plays, little horses, tiny see-saws, a n d trains th a t could take you everywhere; flowers an d bushes th at grouped themselves into gardens, balls an d little barrels th at resounded, little rockets th at went off a n d left stars hanging on the heavens. . . . “A nd w hat did your teacher say to this m agician th a t cam e into your classroom ?” som eone asked the child. “O h, he d id n ’t even notice h im ,” she declared. Walk Through a Library I was walking with my favorite teacher th rough the stacks of a library an d saw, in place of the fam iliar books — p reparations in alcohol, skulls in fu r caps, helm ets a n d hoods, trousers hanging from hooks, an d historical puppets out of which sawdust was running. Most of the things were hung w ith black an d w ith good reason. I h ad no desire to uncover them . Suddenly — in the m iddle of the room upon a starem broidered carpet — I saw a child. H e laughed an d stretched out his arm s to m e. I held him up high in the air and showed him to my teacher. “I know him alre ad y ,” he lau g h ed gaily. “H e is my own p o em .” — Translation by C.B. 25 Destruction and New Start o f the Original W aldorf School AL LANEY O n a hillside overlooking the city of S tu ttg a rt in the valley of the N eckar there was enacted on M arch 30, 1938, a scene of great impressiveness which, taken together w ith its sequel seven years later and its predecessor in 1919, form s a tab le au of three scenes of great im p o rtan ce for ed u cation in G erm any an d th ro u g h o u t the world. These three scenes in the life of the Free W ald o rf School are d ram atic exam ples of the triu m p h of m a n ’s spirit over adver­ sity an d the willingness of people to suffer for the sake of an educational ideal. T he Closing under H itler O n this spring day of 1938 T h e W ald o rf School, one of the last free institutions u n d e r N ational Socialism, was being clos­ ed by governm ent ord er a n d the final assembly was m ade the occasion of a pilgrim age by friends of the school who h ad cherished a n d su p p o rted it th ro u g h th e d ark days an d h ad now com e to jo in w ith the students an d teachers in a pledge of renew al some day an d by some m eans. T h e great hall of the school on the hill was packed. A t the front n ear the stage were the small children swirling about their teachers like tiny wavelets lap p in g at a n island. B ehind sat the older classes, each w ith its teacher; an d the young people of the u p p e r grades closed the ranks. T h e rows at the back were filled w ith grow n-ups, m en and wom en from m any walks of life, parents of present an d form er 26 pupils, students from the W aldorf T ra in in g College and the friends who h ad come from afar. From the balconies hundreds of form er pupils looked down, once m ore at hom e for a brief m om ent in the school they h ad loved. Everyone present, even the smallest children who h ad no u n d erstanding of the workings of the political tragedy in which their lives had been caught up, knew w hat this last assembly m eant. How different from the other joyous occasions when they had g ath ered here! T h e cerem ony was sim ple and direct. Each teacher spoke to his or her class, a n d th rough his words each child received the message th a t his beloved school was no m ore. T h en the school orchestra played the Fifth Sym phony of Beethoven, which one of the school’s founders h a d called the Sym phony of Destiny. Finally, C ount Fritz B othm er, the school’s ch airm an who had conducted the long a n d painful negotiations w ith the Nazi authorities, rose. T he building in which they were assem bled, C ount B othm er said, h ad been constructed on the form of a cross a n d from the spot where he stood, at the junction of the two arm s, the founders of the W ald o rf School h ad often spoken to parents and pupils. “H e re ,” he said, “our m ost beautiful a n d impressive festivals have taken place. H ere the h e a rt of the W ald o rf School has shone forth m ost lum inously. This institution is founded on the form of the cross a n d upon the nam e of H im who died upon the cross b u t continues to live in those h u m a n beings who offer H im a dwelling place in their hearts. T herefore, the h e a rt of this school also continues to live.” At this point C ount B othm er asked the assembly to rise, and continued: “I have now the task of pronouncing th a t, upon the decree of the W uerttem b erg governm ent, the W aldorf School is closed. Let us then, w ith the power of love, seal up our school in the deepest recesses of our hearts for the fu tu re .” O n the following day nearly all the thousand an d m ore p res­ ent at this cerem ony were present at an o th er scene as far rem oved as is possible to im agine. T his one was enacted at the S tu ttg art railway station w here A dolf H itler, retu rn in g in 27 triu m p h from the accom plishm ent of the Anschluss in A ustria, stopped off to receive the frenzied Heils of his followers and the hom age-by-order of all the others. T eachers, pupils a n d friends of the now defunct W ald o rf School stood on the fringes of the hysterical crowd, u n ab le to see into the fu tu re for themselves or for G erm any, un ab le even to think beyond the day, b u t know ing in their hearts th a t the day w ould com e, however long delayed, w hen dictators were not a n d education w ould be free again. R e b u ild in g out o f the R uins T h a t day cam e for the W ald o rf School in O ctober of 1945 in vastly different physical a n d spiritual surroundings on the sam e hillside, w hen the school was re-opened u n d e r w hat d if­ ficulties never will be adequately told. But here was living pro o f th a t the words spoken an d the pledge taken in 1938 h ad not been forgotten. T h e once lovely city lay in ruins. Its streets were littered w ith rubble an d the houses were b u rn t-o u t shells. People lived in cellars an d provisional shelters. T h e children o f the town, grow n u p w ithout fathers, presented a pitiful picture as, ra g ­ ged, barefoot a n d hungry, full of restlessness a n d fear and weakened m oral feeling, they played am ong the twisted beam s a n d piles of rubbish or g ath ered cigarette ends on the pave­ m ent to sell at black m arket prices. B ut there on a fragm ent of the wall of the wrecked m ain b uilding of the W ald o rf School, p a in te d in large letters by some form er student, were the words, “W e W ill Be B ack.” These words h a d stood for seven years against b o th the vindic­ tiveness of the Nazi G estapo an d the fury o f A llied bom bings, an d still were there as a symbol th a t the spirit o f freedom h ad not died. A nd so, on the very day the occupation troops en tered S tu tt­ gart, a little group of people em erged from the chaos to m eet in a su b u rb an house a n d discuss the fate of the children. Some were form er teachers a t the W ald o rf School, some were p arents a n d some, form er pupils now grow n to m an h o o d an d 28 w om anhood in a tim e of destruction when all th a t rem ained seem ed to be an anim al-like need to struggle for survival. All h ad carried the school in their hearts through seven years of hardship. T his group was addressed by Dr. Eric Schwebsch, a form er teacher of the school, who told them th a t the words spoken in 1938 h ad not been m ere phrases an d th a t now was the tim e to start again even though the difficulties m ight seem in su r­ m ountable. T h e need to re-open, Dr. Schwebsch said, was urgent, for the hope of G erm any lay with these children who roam ed the rubble and knew not w here to turn. T h e school h a d been bom bed out, its m ain building was a burned-out ru in and all other buildings were badly dam aged. T h e school yard was a huge mass of wreckage th a t only the m ost m odern salvage m achines seem ed likely to clear. But into this mess o f destruction Dr. Schwebsch and his b a n d plunged w ith hardly m ore th an their hands as tools. As they worked, their num bers grew. A t the original m eeting several form er pupils, now grown beyond school age, volunteered to brin g the word to teachers and friends wherever they could be found. O n bicycles they crossed zone lines, searching everywhere, and one by one those teachers who had survived cam e trickling back. All th a t long first sum m er they worked, on the edge of s ta r­ vation, an d the trickle of those in whom the spirit h ad been kept alive grew into a stream . They cam e from wherever they were an d by w hatever m eans of travel they could find as soon as the word h a d been b rought to them . In th a t sum m er the rubble was cleared w ith a few spades an d m any pairs of hands. T h e dam age to m inor buildings was repaired and two provisional wooden structures were built. In a tim e when no building m aterial was apparently to be had, these people somehow found it. T h e ir own hom es were in ruins b u t the school cam e first. T hey acquired the m aterial actually by a com plicated system of b a rte r and exchange in w hich food, cigarettes a n d clothing were m ore valuable th an gold. A nd they h a d enorm ous help from the friendly A m erican m ilitary authorities. 29 In O ctober, 1945, the school re-opened with a solem n and touching cerem ony th a t stem m ed directly from the closing cerem ony of 1938. M ore th a n 500 pupils were present on opening day, twelve com plete grades were form ed, a n d of these only a h an d fu l in the two u p p e r classes h a d been pupils seven years earlier. T h e difficulties these children a n d their p arents h a d to over­ com e in order to a tte n d classes were alm ost incredible. No fam ily h a d enough to eat or enough clothes to go around. Some pupils could come only irregularly because the fam ily h ad only one p air of shoes th a t was shared. T ra n sp o rtatio n was so poor th a t some children from the surrounding country h a d to leave hom e at daw n each day and did n o t get back u n til long after dark. Still they cam e, a n d from the first day the school h a d a long w aiting list of fam ilies eager for their children to atten d . W hile the rest of the city an d the rest of G erm any b e ­ m oaned their fate, the W ald o rf teachers, pupils an d parents began their work, full of faith in the future. An arm y officer present a t the opening said th a t the school was “like a n island of hope in an ocean of d e sp air.” Dr. Schwebsch spoke of the “blessing of a second s ta r t.” F ounding and Growth — “A Lasting H u m a n P urpose” T o u n d e rsta n d w hat h a d taken place here on the hillside, it is necessary now to tu rn to the opening scene of the tab leau w hich was enacted at a tim e of alm ost sim ilar chaos in G erm any. In 1919 the w orld h a d blu n d ered into a peace th a t was a c o n tin u atio n of war, a n d the ideas w ith which m en hoped to b uild a new a n d better w orld could not cope w ith the realities of life. T h e th u n d ersto rm of the First W orld W a r has not tau g h t m en th a t the outw orn conceptions of the 18th and 19th cen ­ turies could no longer apply, for m en h a d slept th ro u g h the storm , em erging from it w ith the sam e basic habits of tho u g h t w ith w hich they entered. T h ere were m en in 1919, however, who recognized the true situation a n d who saw th a t the ideas w ith w hich it was hoped 30 to build a p erm an en t peace were hopelessly o u td ate d an d could produce only confusion. Because of the breakdow n of outer conditions, G erm any was open to new impulses as she h ad never been before, a n d in the m idst of these conditions a farsighted industrialist, Dr. Emil M olt, owner of the W aldorf Astoria cigarette factory in S tu ttg art, cam e to R udolf Steiner, philosopher and ed ucator, w ith the request th a t he found a school for the children of M olt’s 4,250 factory workers. Emil M olt was a m an of w ealth an d great influence, and he was deeply concerned w ith the social and econom ic problem s of the times. He recognized th a t all these problem s h ad their source in the central problem of the h u m an being himself; he wished, in a tim e of econom ic breakdow n and social revolu­ tion, to use his w ealth for a lasting h u m a n purpose. H e believed th a t the most effective way to achieve this was to found a school w here children would receive a truly h u m an education which would help them to take their places in life no m atte r w hat the o uter conditions m ight be. A nd he tu rn e d to R udolf Steiner as the ed ucator whom he considered best able to create such a school. Steiner accepted the task on two conditions: th a t he be free from every political, econom ic or religious control in following his educational principles, a n d th a t children o f every social and econom ic class be ad m itted. T h e school was to be “fre e ,” he said, as an artist is free to create out of the necessities of his m aterial. C urriculum an d teaching m ethods were to evolve from insight into the n a tu re of m an , arrived at by m eans of the in ­ vestigation of supersensible realities according to the disciplines of scientific thought and observation. It was to the w inning of this knowledge an d the developm ent of a clear, contem porary p a th to its achievem ent th at R udolf Steiner h a d devoted his life and it was the recognition by Emil M olt th a t his knowledge aw akened creative capacities in those who worked with it, leading them to practical a n d helpful results, which h ad m oved him to ap p ro ach R udolf Steiner on beh alf of the school he wished to found. This was not to be just one m ore pedagogical experim ent, b u t a response to the spiritual and social needs of the times. 31 T h e faculty w ould be the real leaders of the school and, u n d e r no outside influence, w ould be free to build the school out of its own necessity. T h e school was to be m aintained entirely by gift m oney if th a t were possible, or by gift m oney and tuitions if it were not. T h e ideal w ould be no tu ition fees at all, b u t this proved impossible because of an already im pending terrible inflation in G erm any. T his educational idea was in com plete contrast to the system then prevailing in G erm any, w here the A b itu r, the stiff en tran ce exam ination for the universities, was the goal of secondary education. G erm an children w ent to elem entary public schools w here tuition was free, from the ages of six to ten. T h e n the p arents decided, chiefly according to the state of their purses, w hether the child should go to the Gym nasium for eight m ore years a n d becom e an “in te lle c tu a l,” or stay in the Volksschule a n d p rep are for a m an u a l profession. T h e child’s fu tu re was thus d eterm ined a t the age of ten and the tra d itio n of the G erm an education was to create separate social castes. Dr. M olt purchased for the new school a building th a t had housed a fashionable resta u ra n t, b ringing dow n u p o n him self a t the start the disapproval of the elite of S tu ttg art who had dined there for generations. H ere, Steiner g ath ered together the han d fu l of m en a n d wom en he h ad selected as teachers a n d conducted an intensive course in the new pedagogy with daily lectures, sem inars an d dem onstrations. O n the day the W ald o rf School was scheduled to open, nearly 400 children w ith their fu tu re teachers g ath ered in the courtyard of the form er resta u ra n t building an d were separated into age groups. A nd there, on the spot, Steiner assigned the teachers to the grades, declaring th a t it was necessary to see the teachers in the presence of the children before deciding w hich should take w hich group. T h e school started u n d er the best o f auspices, w ith a cerem ony in a large hall in the center of S tu ttg a rt which followed im m ediately on this initial assembly. T h e hall was filled to overflowing w ith m ore th a n 2,000 persons, am ong 32 them the M inister of E ducation for W uerttem berg, a Socialist who was favorably disposed tow ard the new venture. W ithin a year of its founding the school h ad ab o u t 800 pupils an d at its peak about 1,000; it was lim ited only by its physical capacities. These pupils included boys and girls of every creed an d class and from alm ost every p a rt of the world. T h e curriculum an d teaching m ethods a ttra c te d educators from m any countries who carried them back to their own homes, with the result th at schools w orking with the W aldorf pedagogy grew u p in Sw itzerland, A ustria, H olland, Norway, Sweden, England an d the U nited States. Those who knew the school at this tim e felt th a t here was a group, although still sm all, of young people who could break th rough national barriers a n d conventional, routine thinking to a genuine internationalism which w ould not be satisfied w ith em pty phrases. A nd then cam e 1933 and the rise of H itler to power. From th a t day the W ald o rf School an d the, by now, nine other Steiner Schools in G erm any were doom ed. By their very n atu re they could not conform to the Nazi ideas of education. T h e reasons were bluntly stated in the press of the day. T h e W aldorf Schools developed individuals, whereas the task of education in a N ational Socialist State was to produce N ational Socialists. Tw o such opposed systems of education could not exist in a single state. But ideas a n d ideals such as these live all the m ore in te n ­ sively a n d inw ardly w hen outw ardly suppressed and, as the th ird scene in the tab leau dem onstrated, wherever the spirit lived in G erm any unseen th ro u g h the d ark years, there was an ally for the cause of freedom and a sure collaborator in the task of the re-education of m ankind. There are at present well over 180 R u d o lf Steiner schools in some 20 countries o f the fr e e world, though none behind the Iron Curtain. F ifteen o f these are in N o rth A m erica, where a n u m b er m ore are in the process o f establishing themselves. — T he E ditor 33 Education fo r Adolescents* R U D O LF STE IN ER W h en ch ild ren com e to the age of puberty, it is necessary to aw aken w ithin th em an ex traordinarily g reat interest in the w orld outside of themselves. T h ro u g h the whole way in which they are educated, they m ust be led to look o ut into the w orld a ro u n d them a n d into all its laws, its course, causes an d effects, into m en ’s intentions a n d goals — not only into h u m an beings, b u t into everything, even into a piece of m usic, for instance. All this m ust be b ro u g h t to them in such a way th a t it can resound on a n d on w ithin them — so th a t questions a b o u t n a tu re , a b o u t the cosmos a n d the entire w orld, ab o u t the h u m a n soul, questions of history — so th a t riddles arise in their youthful souls. W hen the astral body** becom es free at puberty, forces are freed w hich can now be used for form u latin g these riddles. B ut w hen these riddles of the w orld a n d its m anifestations do not arise in young souls, th en these sam e forces are changed into som ething else. W hen such forces becom e free, a n d it has not been possible to aw aken the m ost intensive interest in such w orld-riddles, th en these energies transform them selves into w hat they becom e in m ost young people today. T hey change in two directions into urges of an instinctive kind: first into delight in pow er, a n d second into eroticism . *This text consists of excerpts from a lecture given in S tu ttg art on Ju n e 21, 1922. In a few cases the repetitions appropriate for spoken style have been om itted an d sentences condensed. T ranslation by C.B. [C ane] hristyB **A term used to designate all th a t is sentient in m an an d in anim als. 34 U nfortunately pedagogy does not now consider this delight in power and the eroticism of young people to be the second­ ary results of changes in things th a t, until the age of 20 or 21, really ought to go in an altogether different direction, but considers them to be n a tu ra l elem ents in the h u m an organism at puberty. If young people are rightly educated, there should be no need w hatsoever to speak ab o u t love of power and eroticism to them at this age. If such things have to be spoken about d u ring these years, this is in itself som ething th a t smacks of illness. O u r entire pedagogical a rt an d science is becom ing ill because again an d again the highest value is a ttrib u te d to these questions. A high value is put u p o n them for no other reason th a n th a t people are powerless today — have grown m ore and m ore powerless in the age of a m aterialistic worldconception — to inspire tru e interest in the w orld, the world in the widest sense. . . . W hen we do not have enough interest in the world aro u n d us, then we are throw n back into ourselves. T ak en all in all, we have to say th a t if we look at the chief dam ages created by m odern civilization, they arise prim arily because people are far too concerned w ith themselves and do not usually spend the larger p a rt of their leisure tim e in concern for the w orld b ut busy themselves w ith how they feel an d w hat gives them p ain . . . . A nd the least favorable tim e of life to be self­ occupied in this way is d u rin g the ages betw een 14, 15 an d 21 years old. T h e capacity for form ing judgm ents is blossom ing at this tim e a n d should be directed tow ard w orld-interrelationships in every field. T h e world m ust becom e so all-engrossing to young people th a t they simply do not tu rn their a tte n tio n away from it long enough to be constantly occupied w ith themselves. For, as everyone knows, as far as subjective feelings are concerned, p ain only becomes greater the m ore we think ab o u t it. It is not the objective d am age b u t the p ain of it th a t increases as we think m ore about it. In c ertain respects, the very best rem edy for the overcom ing of p ain is to b rin g yourself, if you can, not to think ab o u t it. Now th ere develops in young people just betw een 15, 16 an d 20, 21, som ething not 35 altogether unlike pain. T his a d a p ta tio n to the conditions b ro u g h t a b o u t th ro u g h the freeing of the astral body from the physical is really a con tin u al experience o f gentle pain. A nd this k ind of experience im m ediately m akes us ten d tow ards self-preoccupation, unless we are sufficiently directed away from it an d tow ard the w orld outside ourselves. . . . If a teacher m akes a m istake while teaching a 10 or 12 year old, then, as far as the m u tu a l relationship betw een pupil and teacher is concerned, this does not really m ake such a very great difference. By this I do not m ean th a t you should m ake as m any m istakes as possible w ith children of this age.. . . T h e feeling for the tea c h e r’s au thority will flag perhaps for a while, b u t such things will be forgotten com paratively quickly, in any case m u ch sooner th a n c e rtain injustices are forgotten a t this age. O n the o ther h an d , w hen you stan d in front of students betw een 14, 15 a n d 20, 21, you simply m ust not expose your late n t inadequacies an d so m ake a fool of yourself. . . . If a student is u n ab le to form ulate a question w hich he ex­ periences inwardly, the teacher m ust be capable of doing this himself, so th a t he can b rin g ab o u t such a fo rm ulation in class, a n d he m ust be able to satisfy th e feeling th a t then arises in the students w hen the question comes to expression. For if he does not do this, th en w hen all th a t is m irro red there in the souls of these young people goes over into the w orld of sleep, into the sleeping condition, a body of detrim en tal, poisonous substances is p ro d u ced by th e u n fo rm u la ted ques­ tions. These poisons are developed only d u rin g the night, just w hen poisons ought really to be broken dow n a n d transform ed instead of created. Poisons are pro d u ced th a t b u rd en the brains of the young people w hen they go to class, a n d g ra d u a l­ ly everything in them stagnates, becom es “stopped u p .” This m ust a n d can be avoided. B ut it can only be avoided if the feeling is not aroused in the students: “Now again the teacher has failed to give us the rig h t answer. H e really h a sn ’t answ ered us at all. W e c a n ’t get a satisfying answer o ut of h im .” Those are the late n t inadequacies, the self-exposures th a t occur w hen th e children have the feeling: “T h e teacher just isn’t up to giving us th e answers we n e e d .” A nd for this 36 inability, the personal capacities a n d incapacities of the teacher are not the only determ ining factors, b u t ra th e r the pedagogical m ethod. If we spend too m uch tim e p o uring a mass of inform ation over young people at this age, or if we teach in such a way th at they never come to lift their doubts an d questions into consciousness, then the teacher — even though he is the m ore objective party — exposes, even if indirectly, his laten t in ­ adequacies. . . . You see the teacher m ust, in full consciousness, be perm eated th rough and th ro u g h w ith all this when he deals w ith the transition from the n in th to the ten th grades, for it is just with the entire transform ation of the courses one gives th a t the pedagogy m ust concern itself. If we have children of six or seven, then the course is already set th ro u g h the fact th a t they are entering school, a n d we do not need to u n d e r­ stand any other relationship to life. But w hen we lead young people over from the n in th to the ten th grade, then we m ust p u t ourselves into quite an o th er life-condition. W hen this h a p ­ pens, the children m ust say to themselves: “G reat th u n d er an d lightning! W h a t’s hap p en ed to the teacher! Up to now we’ve thought of him as a pretty brig h t light who has plenty to say, b u t now he’s beginning to talk like m ore th an a m an . W hy, the whole w orld speaks out of him !” A nd when they feel the m ost intensive interest in p a rticu la r world questions a n d are p u t into the fo rtu n a te position of being able to im p a rt this to o th er young people, then the world speaks out of th em also. O ut of a m ood of this kind, verve (Schw ung) m ust arise. Verve is w hat teachers m ust brin g to young people at this age, verve w hich above all is directed towards im agination; for although the students are developing the capacity to m ake judgm ents, jud g m en t is actually borne out of the powers of im agination. A nd if you deal w ith the intellect intellectually, if you are not able to deal w ith the intellect with a certain im agination, then you have “misp layed,” you have missed the b o at w ith them . Young people dem an d im aginative powers; you m ust ap proach them w ith verve, a n d w ith verve o f a kind th a t co n ­ 37 vinces them . Scepticism is som ething th at you m ay not bring to them at this age, th a t is in the first h alf of this life-period. T h e m ost dam aging jud g m en t for the tim e betw een 14, 15 a n d 18 is one th a t implies in a pessimistically knowledgeable way: “T h a t is som ething th a t cannot be know n.” This crushes the soul of a child or a young person. It is m ore possible after 18 to pass over to w hat is m ore or less in doubt. But betw een 14 an d 18 it is soul-crushing, soul-debilitating, to introduce them to a certain scepticism. W h at subject you deal w ith is m uch less im p o rta n t th a n th a t you do not bring this debilitating pessimism to young people. It is im p o rtan t for oneself as a teacher to exercise a certain am o u n t of self-observation an d not give in to any illusions; for it is fatal if, just a t this age, young people feel cleverer th an the teacher d u rin g class, especially in secondary m atters. It should be — and it can be achieved, even if not right in the first lesson — th at they are so gripped by w hat they hear th at their atten tio n will really be diverted from all the tea c h e r’s little m annerism s. H ere, too, the teach er’s laten t inadequacies are the m ost fatal. Now if you think, my d ear friends, th a t neglect of these m atters unloads its consequences into the channels of instinc­ tive love of power an d eroticism , th en you will see from the beginning how trem endously significant it is to take the e d u c a ­ tion of these young people in h a n d in a bold a n d generous way. You can m uch m ore easily m ake m istakes w ith older students, let us say w ith those at m edical school. For w hat you do a t this earlier age works into their later life in an extraordinarily devastating way. It works destructively, for instance, u p o n the relationships betw een people. T h e right kind of interest in o th er h u m an beings is not possible if the right sort of w orld-interest is not aroused in the 15 or 16 year old. If they learn only the K ant-L aplace theory of the creation of the solar system and w hat one learns through astronom y an d astrophysics today, if they cram into their skulls only this idea of the cosmos, th en in social relationships they will be just such m en an d wom en as those of our m odern civilization who, o u t of anti-social impulses, shout ab o u t every 38 kind of social reform b u t w ithin their souls actually brin g a n ti­ social powers to expression. I have often said th a t the reason people m ake such an outcry ab o u t social m atters is because m en are antisocial beings. It cannot be said often enough th a t in the years betw een 14 and 18 we m ust build in the m ost careful way upon the fu n ­ dam entally basic m oral relationship betw een pupil a n d teacher. A nd here m orality is to be understood in its broadest sense: th at, for instance, a teacher calls up in his soul the very deepest sense of responsibility for his task. T his m oral attitu d e m ust show itself in th a t we do not give all too m uch acknow ledgem ent to this deflection tow ard subjectivity and one’s own personality. In such m atters, im ponderables really pass over from teacher to pupil. M ournful teachers, u n ­ alterably m orose teachers, who are imm ensely fond of their lower selves, produce in children of just this age a faithful m irro r picture, or if they do not, kindle a terrible revolution. M ore im p o rta n t th a n any approved m ethod is th a t we do not expose ou r laten t inadequacies a n d th a t we ap p ro ach the children w ith a n a ttitu d e th a t is inw ardly m oral th ro u g h and th r o u g h .. . . T his sickly eroticism which has grow n up — also in people’s m inds — to such a terrible extent appears for the m ost p a rt only in city dwellers, city dwellers who have becom e teachers an d doctors. A nd only as u rb a n life trium phs altogether in our civilization will these things come to such a terrible - I do not w ant to say “blossom ing” b u t to such a frightful — degeneracy. N aturally we m ust look not at appearances b u t at reality. It is certainly quite unnecessary to begin to organize educational hom es in the country im m ediately. If teachers and pupils carry these sam e detrim en tal feelings out into the c o u n ­ try a n d are really p erm eated by u rb a n conceptions, you can call a school a country educational hom e as long as you like, you will still have a blossom ing of city life to deal w ith. . . . W h a t we have spoken ab o u t here today is of the utm ost pedagogical im p o rtan ce and, in considering the high school years, should be tak en into the m ost earnest consideration. 39 To Have, To Be and To Become W ords T o A n A udience O f Y oung People KARL EGE This short address, w hich speaks to yo u n g people out o f long life experience and spiritual insight, is an exam ple o f how it is possible to reach into the realm where their inner questions are rooted, and by helping th em to raise these affirm atively in ­ to consciousness, shed light upon their answers. It is taken fr o m Karl E g e ’s recently published book, An Evident N eed of O ur Times, which deals with aspects o f W a ld o rf education in relation to the dilem m as o f our age, and with its fu r th e r developm ent in a new direction indicated by R u d o lf Steiner at the end o f his life. — T he E ditor My dear young friends — T o night I shall speak to you ab o u t two small words: — to have a n d to be — having a n d being — or we m ight say — I have an d I am . T o illustrate w hat I m ean, I shall tell you a story. A young soldier — it is the tim e of the First W orld W ar — who h a d been poisoned by m u stard gas in the trenches, had developed a lung hem orrhage. He knew w hat this m eant. D u r­ ing the seven or eight m onths th a t he h a d been in the hospital for treatm en t, h ad he not seen m any o f his com rades die th rough this same event? T hey h a d all actually been suffocated in th eir own blood as it filled th e respiratory tra c t. H e was b rought from a room , where he h a d been w ith h a lf a dozen o ther patients, into a single room — a procedure he knew well a n d w hat it m eant. 40 Reviewing his short life, he considered w hat it h a d b ro u g h t him , w hat h a d been given him : parents, childhood, school, arm y training, the battlefield. H e him self h a d earn ed very lit­ tle — his soldier’s pay. All he h a d he h a d received — it h a d been given to him . A nd then he thought w hat life d u rin g forty, fifty, sixty years m ight b ring him . H e im agined w ealth, h ealth, a successful, im p o rta n t career, a happy fam ily life — all th a t a lucky destiny m ight bring. All th a t he m ight “h a v e .” A nd yet, in the end, all of this he w ould have to leave again. T here was n o thing o f all these worldly goods he could take w ith him . W as it so terrible, then, not to have all of this? All th a t I “have” at this m om ent a n d leave behind m e — he thought to him self — is my body w hich gave m e an existence on this plan et e a rth . A nd yet I a m , a n d the m an n e r in which I experience my own being will not go from m e as does my body. O f w hat n a tu re then is this “I a m ” an d w hat kind of ex­ istence will it have — in w hat environm ent? Suddenly, as he po n d ered thus, there was w ithin him a feel­ ing of inner light an d w ith it the conviction — not a belief — b u t a knowing, th a t there is an o th er life w here I am . B ut our young m an d id not die. A nd it took him quite some tim e to realize th a t his life h a d to continue here on this side of the threshold. T his experience, however, of “to have” a n d “to b e ” guided him a n d determ ined his strivings, his interests and his deeds thro u g h o u t the next fifty years. A nd d u rin g these fifty years he h a d all m an n e r of ex­ periences. H e lived the life th a t he h a d im agined. H e did not have w ealth, full health , success, o r m any of the things he h a d pictured. But he h a d other, m ore extrao rd in ary experiences: spiritual riches, th e joy of work, struggles, suffering an d gifts, far beyond any of his im aginings. A nd after m any w anderings, he h a d a hom e, a g arden, a car a n d all the m any things th a t life h a d b ro u g h t him . T h e n once again, he lay in a hospital very ill w ith pneum onia. H e spoke w ith the m an in the bed next to him . A strong m an who h a d w orked h a rd all his life. B ut the words they exchanged becam e fewer, his voice w eaker, an d th en one 41 night he died. T hey carried him away, w ith the few earthly belongings he h a d b rought w ith him , a n d the room was e m p ­ ty. H ere again was a n experience of the “to have” and the “to b e ” — a n d a few days later, as he was being driven hom e th ro u g h the clear, sun-filled air of w inter, there stood before him vividly the question: W h a t th en do I now own in reality? W h at is really mine? All the physical things I have acquired: my hom e, this car, my body — I shall have to leave them all even as did my co m p a­ nion in the hospital. I am only the user. But w hat about all th a t I have experienced th ro u g h living w ith them , acquiring them , using them . Does this m ean nothing? W h at can “I , ” this “I a m ,” really call my own? A nd there cam e to his m ind an o th er sm all word: “to becom e.” Becom ing, m atu rin g , the gaining of life experience an d in ­ sight, of m oral developm ent th rough th e good a n d the evil w hich I have done; this is evolution. Evolution is the m ethod of creation, o f becom ing. Yet I cannot achieve this alone. I have not bro u g h t m yself into existence. W h at has been given to m e, a n d the way it has been given, have all been provided. How do I myself exist? W ho am I? By m eans of an im age, we m ay becom e aw are of an answer. T h e p lan t is draw n up out of the darkness of the e a rth by the light of the sun. It needs the sun forces. W ithout them it perishes. So, too, am I draw n forth into existence by a spiritual sunlight — th a t Light of the W orld W ho said: I am the W ay, the T r u th an d the Life. Just as the p la n t’s life — so is my being, a gift. Pondering how it is given, w hat is given, an d in w hat way I use it, I becom e aw are o f the reality o f destiny — of the p a tte rn by which this gift is given, grows a n d becomes — destiny, both cosmic a n d personal. Standing thus before this mystery of my own being, I look u p to the creative w orking of a divine will a n d am filled with the striving to grow tow ards it, as does the plan t, to become its tru e instrum ent. In its presence, g ratitu d e an d confidence 42 grow strong — confidence th a t there is an inner necessity and lawfulness related w ith my innerm ost self in all th a t happens to m e, while, on the other h a n d , w ith sharp awareness, a deep sense of responsibility awakens. For all this — this gift — is given into my own hands. W h at use will I m ake of it? W h at will it becom e th ro u g h me? T his becom ing is now not only a gift, but my own deed, my tran sfo rm atio n of the “to have” into the “to b e .” H ere, in this act o f becom ing, e a rth a n d sun — just as w ith the p lan t, b u t now in free activity th ro u g h m e — are un ited in one deed of creation. H erein lies my tru e being. T his is my own — th a t I am free to work u p o n a n d to particip ate in — b u t also to neglect. It is, thus, m y own free goal, a n d at the sam e tim e, the goal of the highest spiritual beings who have created m e — the fru it of their work of c re a ­ tion. T his will stay w ith m e th ro u g h all eternity, w hen all else is left behind. Looking about us at this critical p oint of tim e in w hich we live, when the prim e em phasis in life is on “to h a v e ,” w ith the result th a t h u m a n civilization hangs on the brin k of d estru c­ tion, m ust we not say: T oday it is no longer a question of “to be or not to b e ,” b u t it is a question of “to becom e or not to becom e." T h e divine beings say to us: H ere are the powers a n d help you need. W e give them to you. B ut you have to recognize an d n u rtu re them , to take them an d use them . — T his is your freedom : a n d therefore, also, your responsibility. Just as food is given to you by N a tu re — th o u g h you m ust first cultivate it, prep are an d e a t it if you are not to die; ju st as you m ust digest a n d transform it if you are to be nourished a n d to grow — so spiritually you m ust cultivate, digest a n d transform the life a n d destiny th a t is given you, in ord er to becom e. It lies in your freedom to recreate the given, a n d thereby to create, to becom e yourself — your highest goal, so th a t you m ay in tu rn becom e a giver. T h ro u g h this m ystery of “b eco m in g ,” you will in this way — even as the ripening p la n t — provide a new store o f living nourishm ent for others, for the w orld a n d for all eternity. 43 About Goetheanistic Science HANS G EBERT T h e fear th a t science, a n d the technology it has fathered, m ight destroy o u r environm ent is often expressed nowadays. This fear itself is a m anifestation of a new spirit w hich has been a b ro ad since the m iddle of this century. Some of its o ther m anifestations are the w idespread rejection of A m erican work ethics, the increasing refusal to recognize m erit as a valid basis for advancem ent in society, and the search for m ethods of expanding consciousness by use of drugs, m ed itation, or in other ways. C harles Reich is a typical p ro p h et of the m ore ex­ trem e m anifestations of this new sp irit.1 T h e change of outlook he an d others describe is as profound as the one w hich started aro u n d the 15th century an d led to the Renaissance in Italy a n d to H um anism fu rth e r n o rth . T h e change from A ristotelian science to N ew tonian science was p a rt of th a t change in outlook. T h e cosmos a n d the e a rth were experienced quite dif­ ferently before an d after th a t change. H anson, in a searching inquiry regarding scientific m ethod, asks w hether K epler and Tycho B rahe each saw the sam e thing w hen they w atched the d a w n .2 They were contem poraries, b u t Tycho B rahe accepted the theory of a stationary ea rth and a m oving sun, while for Kepler the state of affairs was reversed. H anson suggests in effect th a t observation cannot be separated from the way one thinks about phenom ena. C ertainly the change of view-point m ade old questions m eaningless a n d suggested new ones. For instance, a question ab o u t the influence of the stars on te r­ 1.R eich, Charles: The Greening o f Am erica (R andom House, New York, 1970). 2.H anson, Norwood R .: Patterns o f Discovery (Cam bridge University Press, London, 1958) p. 5. 44 restrial events was very m eaningful in the A ristotelian universe. T h e ea rth was at the center of the sphere of each of the planets, a n d the m otion of the planetary spheres conditions the m ovem ent of the visible spot of light we call the plan et. In the N ew tonian universe — in w hich the m otion of the planets is determ ined by the su n ’s gravitational forces, in w hich the same forces at work betw een the planets have very sm all effects, an d the forces exerted by the fixed stars have negligible effects — astrology becomes a dubious science. O n the o th er h a n d it becomes of great interest to investigate how terrestrial objects a ttra c t or repel each o ther an d how they move w hen propelled by such forces. T h e changes described go h a n d in h a n d w ith a breathtakingly ra p id developm ent of the capacity for abstract m ath em atical thought. W h eth er the new science caused the developm ent in m athem atics or vice versa is a question d if­ ficult to answer. P erhaps it is best to content ourselves by noting their m u tu a l influence. I shall try to characterize in this article some aspects of a new m ethodology in science, w hich began to develop in the m iddle of the last century. I believe th a t it accom panies the changes noted by Reich a n d others, ju st as the rise of N ew ­ tonian science accom panied the transition from a feudal socie­ ty to the m odern age. Since G oethe, the G erm an poet-statesm an-scientist, was one of the first consistent practitioners of this m ethod, it has been called G oetheanistic science. New questions are only just a p ­ p earing in G oetheanistic science because it is still in its infancy an d the results o b tain ed are not yet very significant. However, we know how this change calls on new faculties of the h u m a n psyche, an d I shall concentrate on th a t m ost im p o rta n t aspect. O nce this has been ap p reciated it will also becom e clear w hat new results can be expected. O ut o f G o ethe’s W ork W hen G oethe left Strassburg as a young m an of twenty-two, he rem arked on the ap p aren tly com pleted tower of the cathedral in a way w hich foreshadows the scientific m eth o d he 45 was to develop later on. (M any people, including myself, have m istakenly applied the following anecdote to the unfinished tow er.) D uring his stay in Strassburg, G oethe h a d been fascinated by the cath ed ral. H e h a d exam ined it u n d e r all possible lighting conditions. Reflecting on the way in which its architecture com bined the m ajestic w ith the agreeable, he developed a view new to him about G othic arch itectu re in general an d about its im portance for G erm any in particu lar. H e n ot only observed a n d sketched the cathedral, b u t went so fa r as to use the tower to cure a predisposition to vertigo from w hich he suffered. A gain a n d again he clim bed to a small, un p ro tected p latform ju st below the top of the tower, fighting the giddiness u n til it no longer occurred. H e tried to experience the building in as m any ways as he could. W hen he was ab o u t to leave Strassburg he rem arked to friends th a t the tower was incom plete. H e also sketched w hat it w ould have looked like h a d it been finished. O ne of the friends confirm ed from the original plans th a t Goethe was right in his projec­ tions. W hen asked who told him about the original design Goethe replied: “T h e tower itself. I observed it so long a n d so attentively an d I bestow ed on it so m uch affection th a t it decided a t the end to reveal to m e its m anifest secret.”3 T h ro u g h observation, exercise a n d m ental effort he h a d p e n e trate d to an im perceptible reality, to the idea of the architect. T w enty years later G oethe used the sam e m ethod in his study of botany. His interest was sparked by practical con­ siderations of forestry a n d h o rticulture. Once his curiosity was aroused, he studied the then available academ ic work, in ­ cluding L inne’s system of classification. He took every o p p o r­ tunity to observe plants d u rin g his m any journeys, a n d to collect an d sketch specim ens. Using the same m ethod as when studying the cath ed ral, G oethe p en etrated once again to fu n d am en tal ideas. T h e first of these is the idea of m eta m o r­ phosis. H e saw all p lan t organs as m etam orphosed leaves. He n oted first how the leaf form changes as we ascend the stem. 3.G oethe, Johann W olfgang: D ichtung und, W ahrheit, p art III, Book II, (translated by the author). 46 T h e lowest leaves are usually least, the highest ones m ost, dif­ ferentiated. It is not very difficult to recognise the parts of the calyx an d the petals as m etam orphosed leaves — the tendency to becom e m ore ethereal is continued until the petals are very th in an d colored. It is m ore difficult to recognise stam ens as m etam orphosed petals. However, one can occasionally find flowers, particularly cultivated ones, w here a petal appears in the place of a stam en. T h e m any-petalled, cultivated rose has, according to Goethe, developed from the wild rose by breeding, so th a t m ost of the stam ens of the la tte r have reverted to petals.4 His second fu n d am en tal idea is m ore difficult to m ake clear. D uring his journey to Italy, G oethe visited the botanical g arden in P ad u a an d wrote in his diary: “H ere, w here I have been faced w ith plants in a quite new m anifoldness, the thought springs to life th a t perhaps all p lan t form s can be developed from o n e . . . . ” Six m onths later, having visited Sicily, G oethe wrote to H erder: “M oreover I have to confide to you th a t I am quite close to unravelling the secret of the c re a ­ tion an d organization of plants, an d th a t it is as sim ple as one can im agine.. . . T h e m ain point from w hich everything else stems I have grasped quite clearly a n d all the rest I can see in outline; a few finer points only have still to be determ ined. T h e archetypal p la n t ( Urpf lanze) will be the strangest creatu re in the world, — a creatu re for w hich n a tu re herself will envy m e. W ith this m odel an d the key to it, one can invent w ithout end plants which are true to form ; th a t is they could exist even if they don’t exist in reality. . . . ” G oethe h ad in m in d not the form of an actual p lan t from w hich others develop, as m ight be postulated by a theory of evolution. H e h ad in m ind a supersensible m odel; w hen he described it to Schiller after his re tu rn to W eim ar, he also sketched it. Schiller called it an idea, a n d G oethe replied: “It is all right w ith m e — if I have ideas w ithout being aw are o f it an d can even see them with 4.Goethe, Jo h an n W olfgang: The M etam orphosis o f Plants (translation of: Die M etam orphose der Pflanze, taken from the British Jo u rn al of Botany and published by Bio-Dynamic Farm ing & G ardening Association, Spring Valley, N.Y .). 47 my eyes.”5 Perhaps the archetypal p lan t can be likened to the general idea of a style of b u ilding from which an architect could derive m any different edifices. Goethe certainly was con­ vinced th a t he h a d fath o m ed the p lan according to which n a tu re creates plants. For a study of G oethe’s m ethod it is significant to know how he was guided to these new thoughts. H e says th a t a study of Rousseau, who was an a m a teu r botanist, suggested th e d irec­ tion in w hich to look.6 H e indicates in the sam e essay th a t “he who has love” (der L iebhaber) is m ore likely th a n the academ ic scientist to use a m eth o d w hich is integrative and holistic. (A m a te u r a n d L ie b h a b er, one French the other G erm an, b o th share the m ean in g of “love” in th eir root stru c ­ ture. It is tem p tin g to translate L iebhaber as connoisseur, w hich is derived from the F rench an d m eans “know er,” an d it is significant for G oetheanistic science th a t the “know er” a n d the “lover” becom e one.) G oethe studied academ ic scientists b u t transcended the systems created by them . H e did not despise the systems because he recognized th a t they show how the supersensible reality has m anifested in the physical world. In his work on color, G oethe shows how his m ethod can be applied to inorganic sciences. T his has been described in two recent articles7 a n d will, therefore, not be tre a te d here. In general Goethe tries in inorganic science to p en etrate to w hat he calls the archetypal phenom enon (U rphaenom en) in each connected cluster of phenom ena. For instance in the study of heat, expansion a n d a tte n u atio n are archetypal phenom ena. T hey are seen in their purest form w hen h eat radiates from a hot body. T h e h e a t is dissipated, expands out into the cosmos as rapidly as possible an d equally in all directions. In the ex­ pansion of solids, liquids, an d gases the phenom ena are seen 5.G oethe, Jo h an n W olfgang: Glueckliches Ereignis (Essay in H eften M orphologie," 1817). “Zur 6.G oethe, Johann W olfgang: Geschichte meines Botanischen Studium s (In H eften “Zur M orphologie," 1817). 7.G ebert, Hans: G oethe’s W ork in Color (M ichigan A cadem ician, Vol. III, No. 3, W inter 1976). Zajonc, A rth u r G.: Goethe's Theory o f Color and Scientific In tu itio n (A m erican Journal of Physics, Vol. 44) p. 327. 48 as conditioned by properties of m aterials a n d they can be recognized also in h e a t conduction a n d convection. T h e G oetheanistic scientist orders phenom ena by m eans of ideas derived from the n a tu re of the events he is studying. In c o n ­ tradistinction, established science often tries to reduce phenom ena in one field to laws derived from an other. H eat rad ia tio n becomes in established science a special case of electrom agnetic rad ia tio n akin to light and radio waves, while heat conduction is reduced to statistical processes am ong the atom s constituting m atte r. W h at belongs together for G oetheanistic science is often separated in established science. T h e unity which established science tries to achieve by deriving as wide a range of phenom ena as possible from properties of atom s or sim ilar constructs, is atta in e d quite differently by G oetheanistic science. T h e G oetheanistic scientist tries to find laws w hich connect the different forces an d phenom ena in the inorganic world. H e establishes, for instance, how h eat is co n ­ nected w ith chem ical processes, w ith electric currents, with friction. He tries to elucidate the n a tu re of each process and force, an d to determ ine the p a rt each plays in the nexus of world events. His ap p ro ach is ontological a n d he attem pts to show the cosmos as a unity form ed by the harm onious w orking together of m any parts, each of w hich can, to some extent, be studied alone. D evelopm ents Since Goethe R ecently Maslow has described a new m ethodology of science w hich seems to have a good deal in com m on w ith th a t of Goethe. H e distinguishes betw een experiential knowledge an d spectator knowledge. A bout this last he writes: You look th ro u g h the m icroscope or telescope as th ro u g h a keyhole, peering, peeping, from a distance, from outside, not as one who has a rig h t to be in the room being peeped into.. . . H e can be cool, detached, em otionless, desireless. . . . 8 A bout experiential knowledge he writes: 8.M aslow, A braham H .: T he Psychology o f Science (H arp er & Row, New York, 1966, C hapter 6). 49 T h e good experiencer gets utterly lost in the present. . . . Selfconsciousness is lost for the m om ent. . . . In the fullest experiencing a kind of m elting together of the person experiencing with th a t w hich is experienced occurs.. . . T h e experiencer becomes m ore ‘in n o ce n t,’ m ore receptive w ithout questioning, as children are. In the purest experience the person is naked in the situ a ­ tion, guileless, w ithout expectations or worries of any kind, w ithout shoulds or oughts, w ithout filtering the experience th ro u g h any a priori ideas of w hat the ex­ perience should be. . . . 8 In this connection Maslow speaks also of “im provem ent of knowledge by love.” He believes th a t such knowledge can be objective in quite a new sense, if by objective knowledge we m ean knowledge o f an object as it is in itself, u n a ffected by our predilections or prejudices. H e writes: “Briefly stated, my thesis is: if you love som ething or som eone enough at the level of Being, th en you can enjoy its actualization of itself, which m eans th a t you will not w ant to interfere with it, since you love it as it is in itself.”9 It could easily be objected th a t G oetheanistic science as described so fa r has none of the accuracy, reliability and precision of science as we know it. T h e question could arise: Is G oetheanistic science perhaps just an easy option for a few mystically inclined m alcontents who canno t b ear the rigor and intellectual discipline of established science? T his would relate well, it m ight be objected fu rth er, to m uch else which goes by the nam e of counter-culture a n d cannot be called culture in any accepted sense of the word. These doubts w ould be justified if there did not also exist a body of philosophical work which provides for it a lucid and precise basis. G oethe him self does not a p p e ar to have analysed his m ethod philosophically. T h e first such analysis was provided by S tein er.10 His work m akes it possible for G oethe’s m ethod to be applied in spheres which he him self never touched. S tarting 9.o p. cit. , ch. 11. 50 from the work of G oethe a n d also from th a t of K ant and Fichte, Steiner developed his own philosophy. In his m ajor philosophical w ork11 he shows how the capacities of ordinary thinking can be developed to a level w here the concepts an d ideas it reveals form p a rt of the reality of the w orld. T h e “real object” is, for Steiner, com posed of two parts: one p a rt is given th ro u g h sense perception, the o ther p a rt is revealed by thinking. T h ro u g h the la tte r the object becom es a p a rt of the total nexus of w orld events, w hich has a spiritual aspect discoverable by th inking an d a physical aspect given to the senses. In the addition to ch ap ter V III, w ritten for the second edition (1918), Steiner has this to say about this fully developed thinking: T h inking all too readily leaves us cold in recollection; it is as if the life of the soul h a d dried out. Yet this is really n othing b u t the strongly m ark ed shadow of its real n a tu re — w arm , lum inous, a n d p e n e tratin g deeply into the phenom ena of the w orld. T his p en etratio n is b ro u g h t about by a power flowing th ro u g h the activity of thinking itself — the power of love in its spiritual fo rm .11 Husserl m akes discoveries sim ilar to Steiner’s. He also claims th a t thinking can be detach ed from the sense w orld so th a t in the process a w orld of essences is discovered. Proceeding in this way (a way, w hich in his w ritings is adm ittedly n ot easy to follow), a stage is reached w hen this personal a n d subjective 10.Steiner, Rudolf: Goethes Naturwissenschaftliche Schriften (R udolf Steiner Verlag, 4th ed., D ornach, 1973). and: G rundlagen einer Erkenntnistheorie der Goetheschen W eltanschaung (R udolf Steiner Verlag, 6th ed., D ornach, 1960). Translations: Goethe the Scientist an d Theory o f Knowledge o f G o eth e’s Conception o f the W orld (both, A nthroposophic Press, Spring Valley, New York). 11.Steiner, Rudolf: Philosophie der Freiheit (R udolf Steiner Verlag, 13th ed., D ornach, Switzerland, 1973). Translations: W ilson, Michael: Philosophy o f Freedom (R udolf Steiner Press, London, 1964); and, Stebbing, R ita: T he Philosophy o f Spiritual A c ­ tivity (R udolf Steiner Publications, W est Nyack, New York, 1963). 51 experience com bines w ith other subjects to reach a stage of intersubjectivity.12 B oth Husserl a n d Steiner claim th a t thinking divorced from ordinary sense perception loses none of its clarity and lucidity. They say th a t it becomes not less b u t m ore effective in u n d e r­ standing the world of phenom ena, or the life w orld, to use H usserl’s term inology. Steiner gives special exercises for developing sense-free thinking in some of his books.13 W e are dealing here w ith the developm ent of a new faculty a n d it would not be reasonable to expect this to be easy. W e should not forget th a t Galileo, when using the new concept of a c ­ celeration, m ad e a m istake in his argum ent w hich could be corrected nowadays by any high school student who has had an elem entary physics course.14 I would like to suggest th a t the thought of Steiner and Husserl, particularly of the form er, could becom e an instrum ent for the kind of science described by Goethe a n d Maslow, a n d th a t it w ould provide the a p ­ parently missing accuracy an d rigor. It is clear th a t practitioners of G oetheanistic science would require a new form of training. T h e faculty of feeling would have to be developed to a n u n h e a rd of degree of objectivity. A beginning has been m ade in the sphere of aesthetics. A lready nowadays great scientists such as Einstein a n d H eisenberg m e n ­ tion frequently th a t the decision betw een rival theories or equations is often based on aesthetic judgem ents ra th e r th an on logical ones. This type o f ju dgem ent w ould becom e even m ore im p o rta n t in the transition to G oetheanistic science. It could be hoped on the o th er h a n d th a t the present com ­ m unication gap betw een artists an d scientists w ould dim inish. T h e new a rt of education which Steiner in au g u ra te d aims to m ake the whole teaching process artistic. In this way the feel­ 12.H usserl, Edm und: Cartesian M editations (M artiuus Nijhoff, T h e Hague, 1960, trans. Dorion Cairns) and Die Krisis der Europaeischen W issenschaft u n d die Transzendentale Phenom enologie (M artiuus Nijhoff, T h e H ague, 1976). 13.e .g. Steiner, Rudolf: A n Outline o f Occult Science (A nthroposophie Press, Spring Valley, New York, 1972, ch. 5). 14.G alilei, Galileo: Dialogues Concerning two N ew Sciences (Dover P ublica­ tions, New York, p. 168). 52 ing life of the student is refined a n d he becom es accustom ed to aesthetic judgem ents. C hildren who have been th ro u g h a Steiner or W ald o rf school should, therefore, find it easier to develop G oetheanistic science th a n those who have been ex­ posed to ordinary education. T hey should be in the h a b it of trying to experience knowledge as deeply a n d widely as they can, a n d should have developed a considerable facility for em pathising w ith the w orld. A n extension of W ald o rf m ethods to ad u lt education could well form a beginning for the tra in ­ ing of G oethean scientists. At the end o f this article some speculation m ay be p erm itted based on the results of Steiner’s occult investigations relatin g to the origin and the purpose of the universe. A ccording to this research the m aterial w orld owes its existence to the sacrifices of His own substance by the C reator. T h e cosmos appears, therefore, as the result of Divine Love. God has w ithdraw n, at least tem porarily, from his handiw ork, so th a t h um anity can learn to act independently. T h e thoughts w hich m en find in th eir souls are the reflections of the laws used by the C reator to fashion the world. M any of the early scientists experienced th eir striving as an atte m p t to fathom “the thoughts of G o d .” These thoughts are derived from sense impressions in the first instance. Nevertheless they have value as keys to unlock some of the h id d en powers in n a tu re . W e use them in technology to exploit the resulting forces for w hat appears to be ou r benefit. W hen we use the sam e thoughts for deciding w hat c o n ­ stitutes “ou r benefit” it becom es a p p a re n t th a t, based on finite an d tem poral sense perception as they are, these thoughts lead in practice to one con trad ictio n after an other. Suspicion of these values a n d the search for a w ider conscious­ ness m entioned earlier ap p ear, in this light, as healthy im ­ pulses. Could it be th a t the progenitors of G oetheanistic science are pointing the way out o f the impasse? C ould it be th a t we m ust find the courage not to ab an d o n th o u g h t, as m any critics of science w ould w ant us to, b u t to develop it fu r­ th er u n til we find in it the “love in its spiritual fo rm ” m e n ­ tioned by Steiner? Divine love a n d h u m a n love m ight th en sound in unison for the m u tu a l benefit of the creation an d of m ankind. 53 S T A R S H om ework assigned in a poetry class to develop a sense fo r the m etaphors and analogies in the kingdom s o f nature, m an and the cosmos. The assignment was the fr u it o f goals shared in com m on by the science and literature teacher. O nce stars were tho u g h t to be pinpricks in the wall of heaven. Actually, they are m am m o th balls of enorm ously hot gas, generating energy by nuclear fusion, b u t essentially — or ra th e r apparently — they are points of light rad ia tin g in all directions, able to reach every conceivable position in the universe. T h e star form , the basis of rad ia l symm etry, is found thro u g h o u t n a tu re . Crystals sometim es grow clustered in star p atterns. O ften crude, m ere im plications of the star, generally these clusters grow only in small arcs, b u t sometim es the full form can be seen, fine a n d beautiful. M any p lan t stems show beautiful star form s. Most flowers are star-based, which becomes m ore noticeable if one looks dow n on them from above. If one exam ines an anim al cell at the p ro p er m om ent in mitosis, one sees a very clear star p a tte rn of fibers em an atin g from the centriole. T h e silican shells of diatom s often display rad ial a n d star shapes, w hich are frequently sim ple in p a t­ tern, com plex in detail, a n d b rea th ta k in g in beauty. Jellyfish an d polyps are rad ial as are the Echinoderm s, w hich include starfish. Bone has a p a tte rn sim ilar to those found in diatom shells a n d some p lan t stems. It is interesting to note th a t these are all stru ctu ral supports. O ne is rem inded of this p a tte rn by the nerve cells, especially the ones in the cerebral cortex. T he physical basis for thought is b o u n d up in a star form . T h o u g h t itself is star-rem iniscent — the brig h t core of the idea rad ia tin g illum ination, capable of reaching every m ind in the w orld. A nd so we pass from the m ost pow erful a n d violent forces of n a tu re to the m ost pow erful an d controlled forces of m an. — M ark Taper, 11th grade 54 Literature and The Drama o f Polarities at Puberty CHRISTY BARNES T h e soul of an adolescent is a battlefield. A new tide is rushing into the w aters of his childhood, a n d the two currents m eet in a w hirlpool, whose vortex can suck him dow n into depths of loneliness or fascinating hells, a n d th en lift him to b reath tak in g heights, w here the wide view is swept by a light like daw n on the first day of creation, revealing, as has never been revealed before, the beauty o f the w orld a n d of frie n d ­ ship: an ideal w orld — W hy is it th a t older people have been able to disregard or sully it so? — an inner w orld th a t is deep an d secret beyond any telling of it. These extrem es are his realities. A gainst them he tests his teachers. Do they know anything of his heights a n d depths? W ill they encroach on this inner w orld too far? A re they ignorant of it? W h at m astery have they? C an they grasp or answer the riddles th a t confront him? O ne of the tasks of a high school teacher is to help boys an d girls — th rough the m edium of im agination ra th e r th a n th rough raw experience — to explore these extrem es an d life riddles even fu rth er. H ere he can have no m ore effective col­ laborators th a n the poets, dram atists a n d novelists of great literatu re. T h ro u g h them , the students come to realize th a t now they are no longer alone in their w orld of discovery. These artists plunge w ith them into depths an d delights, a n d voice their own questionings; a n d one or an o th er a u th o r becomes their friend a n d guide. A good English teacher longs to brin g his pupils into direct contact w ith these authors so th a t they can learn from them as 55 Keats learned from Spenser, Dostoyevsky from Gogol, and Melville from Shakespeare a n d H aw thorne. All original authors have ap p renticed themselves to a chosen m aster and followed in their footsteps for a longer or a shorter way. How can a teacher bring ab o u t a sim ilar apprenticeship? Actually it often requires hours or m onths of search for just those works or passages th at give the essence of a m an or a period of literatu re. T h e n a significant im pression can m ake its effect in a relatively short tim e. O n the other h and, it is well w orth ta k ­ ing a precious half h our or m ore o f a M ain Lesson period w hen each student recites the poem he has learned by heart. T h en ask the others if they can rem em ber any of the lines they have just heard. Give extra credit on a quiz for any volunteer m em orization, and it will surprise you how some of them write out ten, thirty, even fifty lines for you! A poem learned by h e a rt will stay w ith them thro u g h o u t a lifetim e. L earning by h e a rt allows tim e for the substance, m ood an d music of a poem to trickle dow n below the head-know ledge of academ ic teaching a n d becom e form ative forces w ithin the life of the feelings a n d the will, developing powers of com passion and purpose. All this belongs to the “econom ics” of teaching. W here does one spend, w here economize tim e in ord er to achieve far-reaching results? All good teachers know these things as far as literatu re is concerned, b u t they often fall short of letting the students learn to write in a sim ilar way — by becom ing the au th o rs’ pupils. W riters themselves have always done this. B ut today in school, we ask pupils to write essays about w hat they read, to analyze an d criticize them . T his sharpens their critical powers a n d is very necessary a n d good. B ut it is one-sided. It strengthens no im agination, no productive ability, encourages no b re a d th or variety of style. A fter read in g C haucer, let the class practice C h au cer’s a rt of p o rtra itu re , using his swift, econom ic strokes an d a b ru p t tr a n ­ sitions, sketching like him the m ost telling articles of dress and c h aracter w ith shrew d h um or. O r let them try H aw thorne’s R em brandtesque use of one ray of light in a large darkness, 56 Em erson’s sure-footed pace o f thought, H a rd y ’s m astery of concrete nouns an d C o n ra d ’s abstract ones, M elville’s splenderous, rolling seas of language an d alliteration. This exercises deep regions of their beings. T h e ir im agination grows tru er, m ore concrete and expansive. — But now soon it will be tim e to take them into the opposite gesture of contraction, to have them analyze, a n d m ake outlines, abstracts a n d precis. It is probably in the te n th g rad e th a t they feel the changes w ithin themselves a n d in their relation to the w orld aro u n d them m ost intensely. Physical p uberty comes earlier, b u t this is a puberty of the soul. Especially at this tim e, expeditions into literatu re an d the w riting of com positions can act as a veritable m edicine for boys and girls. If, for instance, they read and w rite ab o u t the loneliness which they are sure to e n ­ counter — now m ore th a n ever before — they can be helped to value it: to realize th a t just th ro u g h loneliness one can grow, can come to have a sense of one’s own individuality, find com panionship w ith it, an d th rough u n d e rsta n d in g the loneliness of another, becom e a better friend. In their ten th grade study of the origins of Greek d ra m a in the ancient Mystery Schools, they h e a r how the neophyte was b rought to feel a loneliness so deep th a t of itself it gave b irth to devotion — a devotion to a star, a bird, to some th ing or some one other th a n one’s self. Loneliness found its relief and resolution in devotion. L ater the students en counter this same soul-transform ation an d healing in C oleridge’s “A ncient M a rin e r,” B yron’s “Prisoner of C hillion” an d other works. Several tim es I have h a d seniors rem ind m e of this tra n sfo rm a ­ tion in a way th a t told m e th a t they themselves h ad tested such a cure an d found it valid an d helpful. In the works of Aeschylos a n d Sophocles, they com e to see how, on the other h an d , passion reaches its fru itio n th rough — as A ristotle puts it — “vicarious fear a n d pity so intense th a t it causes a catharsis of the soul.” Passion, rightly in te n ­ sified, spills over into com passion. A class m ay well have learned ab o u t the form of the G reek th eater a n d m any of its properties in the n in th grade, b u t it is 57 a pity th at they should not h ear of just such m otions and resolutions of soul at a tim e when they are especially ready an d in need of them . Dionysos and A pollo — Chaos and Cosmos Now we tu rn to the other root of Greek d ram a , to the Dionysian dances. T h e class listens inw ardly to the pounding of rhythm ic footsteps as the two choruses of young m en advance a n d tu rn in strophe and anti-strophe b eneath the flare of torches, m oving an d speaking in resounding unison to the “god w ithin” (our w ord en-thusiasm stems from this), to the upw ard-striving, subjective, chaotic god who longs to grow above an d beyond him self — Dionysos! Two roots of d ram a — one fed by the Mystery Schools, the other by the Dionysian dances — are united in A thens by the actor, Thespis, an d they form the m ighty tru n k of Greek d ram a proper. T h ro u g h the study of Aeschylos, Sophocles and Euripides, the students see how the poet’s relationship to the gods, along w ith his poetic style, grows steadily m ore earthly, whereas the sense of h u m an conscience becomes progressively m ore inw ard, individual an d conscious. A d ram atic workshop using scenes from “A ntigone” can give special reality and power to this study. O n the other h an d , te n th graders come to respect the p ro ­ perties of Apollo, fath er of the nine muses, god of the sun, whose serene regularity, objectivity a n d harm onious, stringent rays encourage yet shape b oth p lan t an d m an from w ithout. It is he whose rhythm ic m usic pervades Greek lyric an d epic poetry. O ne can ask the class to form ulate the contrasting a t ­ tributes of the two gods: Dionysos: inner fire enthusiasm chaos dram atic conflict aspiring individual subjective 58 A p o llo : outer form serenity order m usical harm ony inspiring cosmic objective It is these two gods, also, th a t the ten th grade teacher learns to invoke. Dionysos tells him to throw discretion to the winds, let fire and lig htning loose, to ride the tides o f m elancholy a n d hum or. H e urges him to explore the depths of longing an d all the w onderful subjectivity of the soul. T h e n Apollo comes to his aid an d curbs him a n d the class, as he curbs the horses of the chariot he guides across the heavens. H e discloses the m ajesty a n d force o f form th a t disciplines all creatio n an d chisels it to beauty. So, invoking Apollo, the teacher restricts a n d shapes as he sets an assignm ent. “T h e hom ew ork for tonight is to write a sonnet. R em em ber it is w ritten in p e n ta m eter, not tetram eter. You m ust choose m usical sounds a n d use a t least one a llite ra ­ tion; the thoug ht a n d im ages m ust be clear. D on’t invert the order of a sentence to get a rhym e; d o n ’t p a d w ith archaic ‘do’s’ to keep th e rhythm . You m ust have a m eta p h o r or simile and use color. You m ust be true to n a tu re a n d to ex­ p erien ce,” you tell them , sum m oning u p all your courage a n d decisiveness. T h en , calling on Dionysos, you continue: “O th e r­ wise you are absolutely free to do anything you w ant. You can write of the darkest city, the m ost silent a n d sunlit m o u n ta in top, of your own soul struggles, whales or dragons — of an old w om an. Only start w ith a m ood, a m usical phrase, a w onder or longing, an im age — a n d now, listen!” A nd you rea d them sonnets by Shakespeare, Keats, D onne, Millay an d have them recite the sonnets they have learned till they are fairly soaked in the long, th oughtful line an d m ighty stru ctu re of the sonnet form . “T h e fun really begins w hen you sta rt to re-work the poem s after you have w ritten th e m ,” are your p a rtin g words. O r, if their gasps have been all too despairing, you read them a stunning sonnet w ritten the year before by an eleventh g rad e r they know, a n d they leave w ith the silent resolve to do every bit as well or b e tte r — an d some of them do. W hen the sonnets — (one of them w ritten in perfect tetram eter despite your w arning), some half-tadpole, half-frog, b u t each containing a pearl or g rain of pure gold — com e in to you, you show them how an “a n d ” here or a “th e ” there will tu rn th e verse into pentam eter-, how trite words can be 59 replaced by shining ones, gaudy by clear, abstract by m usical words. A nd a t last the treasures of some of their deepest experiences — now polished, p ru n ed an d clarified — fill you w ith w onderm ent. T h e two gods help you fu rth er. Apollo shows you how to bu ild a lesson as you w ould w rite a poem — w ith structure an d an ear for the right kind of repetition, echo, or even a kind of rhym ing of your subject m atte r, allowing the content to ring out in overtones at m any levels as do m etaphors and similes — an d your p rep a ra tio n takes on a new, refreshing dim ension th a t is rew arded by a deeper, quieter, yet m ore relaxed a tte n tio n from the students. They begin not only to h ear b u t to breathe the lesson in. Dionysos fires you to enthusiasm , tem peram ent, d ram atic change of tem po — com ­ passion. T he In flu en ce o f Geography on Language a n d Poetic Form R udolf Steiner recom m ended th a t the te n th grade history teacher show how geography is a shaper of history “as at this age the students are justifiably m aterialists.” This sam e guide line has proven enorm ously productive in teaching the history of literature. Let us start w ith the southern stream of western literature, w here it originated in Greece, a lan d where there is a balance betw een m ountains an d the sea, betw een the lassitude of the tropics a n d the rigors of the northlands. In this clim ate, m en can live an outdoor life steeped in the daily a n d seasonal rhythm s o f the e a rth a n d the heavens. H e can unfold u n ­ disturbed his own rhythm ic natu re: the n a tu ra l harm ony of b rea th an d h e a rt b eat, which are neither allowed to grow slug­ gish from h eat nor w hipped out of course by the cold. His gestures, too, take on the large, rhythm ic quality of this life. H arm ony and rhythm becom e the criteria for excellence in his athletics and in sculpture — as we see in the proportions of th e h u m an form a n d the fall of the g arm en t folds. They im bue his architecture an d the flow of his poetry. H om er’s 60 dactylic hexam eter is the finest expression of the n a tu ra l re la ­ tionship betw een h e a rt b eat an d b reath , so m uch so th a t, com ­ bined w ith exercises in curative eurythm y, it helps to cure the rhythm ic disturbance th a t underlies stuttering. Peoples of southern climes ten d in th eir language to em phasize vowel sounds — the soul-bearing elem ent of language — whereas n o rth e rn words are b u ilt u p out of the m ore form ed, consonantic elem ent, sounds im itative of the ex­ ternal n a tu re th a t m en m ust constantly com bat. O ne can h ear this shift in ou r own country w hen traveling from G eorgia to M aine — from the w arm , relaxed, w elcom ing draw l, “howahh ya-awll?” to a brisk New E ngland “Hey” or “y ep .” T h e Anglo-Saxons spoke forceful, m onosyllables stam ped w ith the signature of n a tu re herself: crash, crag, sludge, bridge, growl, stream — often four consonants to one vowel. W hereas in th e M aori language o f w arm New Z ealand, the proportions tend to be reversed as in A oteoroa, the nam e for New Z ealand itself; wai nut, water-, a n d m oana, W aiganui. In H aw aiian, too, we find a large p ro p o rtio n of vowels. T h e ancient Greek language keeps a sonorous balance of co n ­ sonants an d vowels. As the students recite lines from St. J o h n ’s Gospel or the Iliad in the original Greek, they experience this as well as how the very stride a n d spear throw of the ancient w arriors have been carried over into the rhythm s a n d harm ony of their verse. A t the sam e tim e they are learn in g such Greek w ord roots as arche, logos, theo, polly, auto a n d m any m ore. T h e study of the lyric takes them u p th ro u g h the L atin to the beginning of rhym e, th en to Italy, France, E ngland. T hey scan an d w rite in a n u m b er of poetic form s ending w ith the sonnet, w hich they have followed from D ante to E. B. B row ning and across the seas to R obinson a n d Millay in this country. In striking contrast to the w orld of the Greeks is the hom eland of the Eddas a n d N orse m yths, of the n o rth e rn stream of poetry, a lan d th a t prepares the class for the study of Beowulf, C aedm on a n d th a t w onderful lyricist Cynewulf. H ere rivers ra n sluggish to the sea th ro u g h sw am plands and fens, swollen by incessant sum m er rains, till the mists rose like 61 furnace smoke, craw ling the horizon in purple coils, th rough w hich T h o r flashed his fiery b eard. Axe strokes fall in the forest. In w inter, ice-blocks sway crashing betw een surge and shore; “Fast to the deck my feet were frozen,” sings the sailor in the “Seafarer” ; beer m ugs bang the boards of the m ead halls, heels ring on the h a rd ground, sword strokes cry out th rough the cold. Face to face w ith storm , snow, hail and rock, the Anglo-Saxons form terse, vigorous, simple words th at echo the elem ents. T h e savagery of the w eather m akes them into doers, attackers. In language as in life, they attack at the start. T h eir rhym e comes at the beginning of the words: “T em pest and terrible toil of the d e e p ,” “G rim a n d greedy his grip m ade read y .” A lliteration is brief, beginning rhym e. T h ere is no tim e for the lingering echoes of “singing, ringing . . . lonely, only.” Gone is the harm ony of Greek m eters, in w hich it is the m usical length of the syllable th a t form s the verse. It is now the force, the weight of the syllable th a t counts. It is the axe-stroke, the stroke of the sword th at bursts in thunderous verse-strokes from the pent lungs of the scops a n d gleem en, now cram p ed in the m ead halls, where they m ust suppress the custom ary gestures of their lim bs and so give vent to them in a new form in their poetry, while strong consonants sculpture the words. R udolf Steiner has indicated this p a th from axe-stroke to A nglo-Saxon poetic rhythm as a concrete exam ple of how physical gesture is carried over into speech. In a c e rtain sense speech is, in its dynam ics, transform ed gesture. W e can even observe how the way in w hich a child walks is characteristic also for the dynam ics of his speech. In A nglo-Saxon poetry, four weighty strokes fall in every verse. T h e small syllables, like so m any wood chips after the axe falls, fly heiter skelter into the air as they will (no tim e to count them ). B ut it is also the b eat of the blood, w hipped awake by the n o rth winds, pounding like T h o r’s ham m er, th a t you hear, and the b rea th th a t comes in short gasps as the w ind tears the words away from the lips th a t form them . T h e re is a sim ilar vitality in the kennings or m etaphorical nouns of n o rth ern poetry: the w hale-path; sw an-road; heather-stepper; w ord-hord. 62 A fter the study of Beow ulf, each m em ber of the class writes some lines in this sam e poetic form , using kennings a n d words of Saxon root a n d perhaps learns a poem by Cynew ulf by h eart. L ater they will read C hristopher Frye’s pow erful play, T h or with A ngels, w ith its gorgeous, Saxon-rooted language, set at the tim e w hen Angles, Saxons a n d Jutes were still at w ar an d St. A ugustine cam e to E ngland. A fter 1066, the southern an d n o rth e rn stream s of litera tu re come crashing together a n d m ill ab o u t in tro u b led p atterns. T h e fam iliar song, “Sum m er is icum en in ,” is one of the first exam ples of the u n io n of n o rth e rn Anglo-Saxon words w ith southern rhym e an d m eter. D uring the centuries from C aesar’s inroads into E ngland up to C haucer, one can trace how various words are picked up an d absorbed into the m ainstream of B rita in ’s language. Finally, out of a host of dialects, C haucer raises one above the rest an d m olds it th ro u g h his genius into a firm tru n k of language, b ro ad enough to up h o ld a n d nourish the boughs of various new literary form s ab o u t to spread themselves ab ro ad in the age of Shakespeare. Now the class learns by h e a rt the first lines of C h au cer’s “P rologue” in the original m id lan d dialect a n d writes verses in royal couplets. T hey try o u t the polaric characteristics of Anglo-Saxon an d L atin-derived words, discovering the elem ental, poetic, alm ost child-like pow er or crudeness of the one, a n d the exact, polished, intellectual d e ft­ ness or pedantic dryness of the other. Em erson tells us th a t “T h e science is false, by n ot being poetic . . . th a t lacks th e connection w hich is th e test of genius. It isolates the reptile a n d the m ollusk it assumes to explain; whilst reptile a n d m ollusk exist only in system, in re la tio n .” It is in this spirit th a t one w ould like to present the study a n d history of language, n o t in isolation, b u t as it cam e about — as an inseparable p a rt of the grow th of literature; not separated off from h u m a n history, b u t as an expression an d pulse o f its life blood. 63 D ram a For this d ram atic tim e of life — the high school years — d ram a itself is one of the m ost potent educative forces th at can be found. R udolf Steiner has given us a key to the problem of evil by separating its n a tu re into two realm s: the extrem e th a t carries us away in a glow of u n earthly bliss an d vague idealism , and the o th er extrem e th a t contracts, hardens and fetters us in m aterialism . B ut the artist in each of us can en ter lovingly into b o th elem ents an d transform them to the uses of creation. H e can refine ex u ltant glow to enthusiasm a n d sharpen the heavy hardness of m a tte r or soul to a fine edge th a t carves form s a n d thoughts to clarity. In d ram a, in which you use n either clay nor p a in t as your m aterial b u t only yourself, all such transform ations are particularly effective. If, in a d ram a class, you can stir all the unresolved chaos, the subjective fear or fire o f a student a n d show him how, w ith every fiber of his being, to pour these, not into selfexpression, b u t into an objectively form ed gesture, exploring w ith him every dynam ic nuance an d concrete detail of it with m atter-of-fact strictness, enthusiasm , h u m o r an d insistence, he comes to experience a sense o f achievem ent, relief a n d joy th at enables him to walk w ith confidence into the next situation th a t confronts him . For w hat has happened? His subjective n a tu re has entered fully into a n d becom e one with a form outside himself, an objective form . T h e walls betw een subject a n d object, betw een him self a n d the w orld outside him self have been broken through, dissolved; an d he discovers, at one a n d the sam e m om ent, b o th the w orld an d himself. In this m om ent he is no longer self-conscious b u t world-conscious a n d so self-confident in dealing w ith the w orld. T his sort o f experience is perhaps the m ost im p o rta n t one we can help to b rin g him . B ut we live in a tim e when m ost of the w orld an d its artists do not believe th a t the gap betw een subject a n d object can be bridged, and this inability leads to a w ide-spread sense of isolation th at causes neuroses, paralysis, eroticism a n d often despair. 64 Exactly for this reason, it is im p o rta n t th a t we realize especially in the realm o f d ram a , th a t the teacher should not use just any m ethod. R udolf Steiner’s insights into speech and d ram a are needed here, if anything m ore, ra th e r th an less, th a n in any other facet of education. Yet it is never enough m erely to read about an a rt or even study it for a short tim e, any m ore th an reading a book on m usic will m ake a pianist. A thorough train in g is called for, or at least a teacher who has set his feet on the ro ad to such training. A rt as Balance E ducators a n d students today are confronted w ith the fact th at academ ic “h e a d ” knowledge does not nourish the whole h u m an being and can often lead to serious problem s of im ­ balance a n d ill h ealth. A fter the “nervous” activity of exams, students let off unused em otional steam by indulging in all kinds of outbursts th a t have no relation whatsoever to their studies or ideals. T o b ring ab o u t a balance of know ing and doing, of h ead and lim bs, sports program s or m ore altruistic a n d purposeful work program s are devised. B ut neither of these really succeeds in inw ardly u n itin g a n d m aking fully perm eable the nervous a n d m etabolic systems. For this, an in ­ ner circulation an d b rea th in g betw een two such activities is needed, one th a t a t the sam e tim e transform s the n a tu re of each. In the h u m an body, this power expresses itself in the restorative, rhythm ic circulation of the blood a n d the b rea th . A nd it is in dealing w ith just these processes th a t the artist is train ed . Like the blood, he is constantly “entering in to ” the one pole, transform ing its properties so th a t they m ay be assim ilated by the other pole, an d th en in like m an n e r enterin g into the o p ­ posite field. So he moves betw een polarities an d lovingly form s a th ird creation born of b o th parents, yet new in itself, u n iting idea an d deed, substance a n d form , the inner an d the outer, the subjective w ith the objective, never stagnating in the one or the other, yet enterin g fully into each. So w hen literatu re an d d ram a becom e artistic activity, then like b rea th in g and circulation, they give life to the soul a n d becom e healing and health-giving forces in education as in life. 65 A Student’s Memories o f R u dolf Steiner LISA D R EH E R MONGES It was a great good fortune th a t allowed m e to m eet R udolf Steiner for the first tim e w hen I was five years old. In 1908, my m other, F rau P aula D reher, h ad becom e a m em ber of the G erm an Section o f the Theosophical Society th a t was under the direction of Dr. Steiner, an d in S tu ttg art in 1911, shortly after the dedication o f the new hom e of the T heosophical Society in the Landhausstrasse 70, my m other h ad an a p p o in t­ m ent with Dr. Steiner. She took m e along and introduced m e to him . W hile I do not rem em ber the events im m ediately before or after this occasion, I clearly rem em ber the occasion itself, which took place in the so-called Blue Room of the new ­ ly dedicated house: Dr. Steiner’s slender figure of m edium height, his black hair, his black eyes, his d ark suit an d black flowing silk tie; an d even today I can feel the kindness that flowed from him to m e as he took my h a n d and put his other h a n d on my head. It was again my great good fortune to becom e one of the first pupils of the original W aldorf School in S tu ttg art which, in 1919, was founded by my uncle, Emil M olt, an d which was u n d er the direction of R udolf Steiner. I was at th at tim e in the 7th grade (the W ald o rf School h ad eight grades from the very beginning) an d was thus able, to a certain extent, to realize the im portance th a t was a ttach ed to the founding of this school u n d er the spiritual guidance of R udolf Steiner. T h e school was dedicated on Septem ber 7, 1919 in the great hall of the S tu ttg art Stad tgarten. Emil M olt spoke the opening words of greeting. T h en R udolf Steiner addressed the assembled 66 future teachers, students, a n d the la tte r’s parents, who were mostly the employees and workers o f Em il M olt’s W ald o rf Astoria C igarette factory, a n d some m em bers o f the A n th ro ­ posophical Society. R udolf Steiner described the basis an d aims of the pedagogy to be p racticed in this school. (See: R u d o lf Steiner in des W aldorfschule, published by V erlag Freies Geistesleben, S tu ttg a rt.) A few weeks p rio r to this dedication festival, a group of children, am ong them my sister D ora an d myself, h a d eurythm y with the Ur -e u ryth m ist, Lory M aier-Sm its. Eurythm y, as an art, was then just seven years old. In the eurythm y p rogram perform ed after Dr. Steiner’s D edication Address, we did rod exercises, and, together with the ad u lt eurythm ists, some hum oresques by C hristian M orgenstern. R udolf Steiner was present a t the rehearsals, which were u n d e r the direction of M arie Steiner — she also recited the texts in the program — a n d d u rin g the dress rehearsal he cam e up onto the stage, took the eurythm y c o p ­ per rods an d showed the tallest girl am ong us how she should hold them on her arm s a n d how we, w ith a slight b en d tow ard her, should receive them . R udolf Steiner called this occasion of the W ald o rf School a “Festival Act in the H istory of M an k in d .” M any vivid a n d precious pictures of R udolf S teiner’s fre ­ quent visits to the W ald o rf School an d to o u r classrooms d u r ­ ing the next five years up to his last illness arise before the eye of the soul. I shall try to describe some th a t are m ost characteristic. It was a tim e of glowing enthusiasm , o f joy and g ratitu d e for all th a t we children received from R udolf Steiner an d our teachers, it was the happiest tim e o f my life an d shines forth in my m em ory in a golden glow. Dr. Steiner h ad directed th a t on every first T h u rsd ay of the m o n th there should take place a so-called M onatsfeir (m onthly festival), in which the whole school g ath ered in the assembly hall, a n d the various grades showed w hat they h a d learn ed in foreign languages, recitation, eurythm y, singing, a n d so forth. Very often D r. Steiner was present at these festivals a n d a d ­ dressed, first, the younger pupils, then us older ones, a n d 67 finally the teachers. I rem em ber his great delight when, at the very first of these festivals, a little boy in the first grade gave him a w ashrag he h a d k n itted for him . T h e little boy h a d a typically Sw abian nam e: H aefe le (L ittle Pot). Dr. Steiner held up the w ashrag an d said, “E uer lieber gu ter H aefe le hat m ir einen W aschlappen gestrickt. M it dem soll ich m ich n u n je d e n Tag waschen." (“Y our dear, good little H aefele has k n itted m e a w ashrag, a n d now I will wash myself with it every d a y .”) T h e n he continued: “D ear children, just as we have to keep o u r bodies clean, so we m ust see to it th at we keep ou r souls p u re and c le a n .” At an o th er m onthly festival Dr. Steiner spoke to us of two wings w hich every child m ust develop. He said: “W e have no wings to fly in the air w ith like the birds, b u t we can grow two wings, one on the right side, one on the left. T h e one on the right side is diligence, the other on the left, attentiveness. If we develop these wings, we shall becom e industrious and capable h u m an beings (t uechtige M enschen) who can fly with them into life.” D r. Steiner invariably ended his addresses to us children w ith the question: “Do you love your teachers?” (“H a b t ihr eure Lehrer lieb?"") to w hich we answered, out of the full conviction of our hearts, with a strong, loud “Yes!” (“J a!"). O ne tim e, after the sum m er vacation, Dr. Steiner spoke to the assem bled children on the first day of the new school year. As he cam e to the end of his address we expected to hear him ask the fam iliar question an d we were inw ardly ready for the fam iliar a n d joyful answer. This tim e, however, he asked: “Did you not forget your teachers?” Now we could not shout “J a!” This req u ired an o th er answer. T h e whole group of about a thousand children hesitated for a m om ent. Dr. Steiner m ade an encouraging gesture w ith both arm s, an d finally we broke into a loud “N ein!” (“No!”). How different was the experience o f a convinced answer in th e negative from the accustom ed one in the affirm ative! A n unforgettable picture: R udolf Steiner w alking across the schoolyard, surro u n d ed by countless children, the little ones literally hanging on his arm s an d legs like grapes on a vine, he 68 struggling to get his arm s free to be able to shake h ands with us older students. Dr. Steiner visited the various grades of the school from tim e to tim e. It was always a trem endous joy for us — our hearts began “to beat h ig h er” — when the door of the classroom suddenly opened an d R udolf Steiner w alked in. W e rose from our seats, a n d Dr. Steiner greeted us w ith b o th arm s raised up high. He listened to w hat the teacher was teaching, and very often he took u p the th re a d a n d continued to teach where the teacher h ad left off. O ne day he entered o u r room — I think we were then in the n in th grade — a n d said ra th e r sternly: “Som ething is w rong in this classroom!” I w ondered w hat he could m ean, a n d th en I discovered th a t there was the wrong date on the calen d ar hanging on the wall. I raised my han d an d said so, an d Dr. Steiner walked over, w ithout saying anything fu rth er, a n d w ith a decided m otion pulled off the page w ith the w rong date. W e h a d sat in th a t room for about two hours w ithout discovering th at the calendar h a d not been brought “up to d a te ,” b u t Dr. Steiner saw it the m om ent he entered the room! D uring a lesson in the History of A rt Dr. Steiner told us: “W hen you take all the colors th a t L eonardo da Vinci used in his Last Supper, p u t them on a disk an d ro ta te this disk very fast, you will get the color w hite. But if you take the colors of the figures of C hrist a n d of Judas Ischariot a n d m ix them together, you will get the color grey.” A m ost m em orable experience was the laying of the fo u n d a ­ tion stone for the new m ain building of the W ald o rf School by Dr. Steiner in D ecem ber, 1921. Students, teachers, R udolf Steiner, M arie Steiner, Emil M olt (the founder of the school), B erta M olt, the architect W eippert, officers of the W ald o rf School Association an d friends of the school were assem bled in the large eurythm y hall in the so-called b arrack. D r. Steiner addressed the assembly a n d read his words w hich were w ritten on a parchm ent tablet, signed by him , and all those m entioned above, as well as by the teachers. These words described the aims and purpose of the activities to be carried on in the newlyto-be-erected building and ended w ith the following three lines: 69 W ith pure intentions A nd good will In the n am e of Jesus Christ. It was a deeply m oving experience to hear Dr. Steiner p ro ­ nounce these words an d th en see him place the p archm ent in a pentagon-dodecahedron of copper which was then im ­ m ediately sealed an d carried out onto the building site where it was lowered into a concrete slab which was then also sealed. Dr. Steiner took a h am m er and with it struck the concrete slab three times. T h e n he did the sam e of behalf of M arie Steiner. A fter this the founder of the school, all the teachers an d every single child in tu rn carried out the same act. This foundation stone escaped destruction when, 23 years later, the building was destroyed in a bom bing attack in W orld W ar II, a n d today it still rests u n d er the en tran ce steps of the now re-erected building. At C hristm as, 1922, I was invited to spend the holidays with a friend a n d her m other an d sister at the G oetheanum in D or­ nach. I accepted this invitation with great joy. T hus, I was able, evening after evening, to h ear Dr. Steiner’s lectures in the great hall of the G oetheanum . T h e public lecture cycle’s title was Der E ntstehungs-m om ent der Naturw issenschaft in der W eltgeschichte u n d ihre seitherige E ntw icklung (T h e B irth of N atu ral Science in W orld History and its Developm ent). Dr. Steiner stood on a platform , surrounded by the beautiful forms of the speaker’s desk, in th e center of the space before the closed cu rtain , beh in d w hich was the stage a n d the small cupola. His deep a n d w arm voice sounded forth in harm ony w ith all form s of the fourteen pillars, the architraves, the paintings in the large cupola an d the pictures th a t were etched into the colored windows. I do not recall the content of the lectures, but Dr. Steiner’s gestures as he was speaking I rem em ber well. W hen he spoke one of his long sentences, he accom panied it w ith a weaving m ovem ent of his arm s a n d hands. O r he would concentrate his gestures or w iden his arm s, even slightly shaking th e fingers 70 when the statem ent he was m aking cam e to a clim ax, a n d this was followed by an all-em bracing m ovem ent of b o th arm s with the conclusion of the statem ent. Tw o years later, w hen Dr. Steiner first gave the eurythm y gestures for the m usical in te r­ vals, it daw ned upon m e th at these a n d Dr. Steiner’s gestures when lecturing h a d the sam e origin. I do not say th a t Dr. Steiner carried out eurythm y gestures when he lectured, b u t these m ovem ents all sprang from the sam e source. O n D ecem ber 31st, on New Y ear’s Eve at five o ’clock, a eurythm y perform ance was given on the great stage o f the G oetheanum . As was his custom , Dr. Steiner spoke some in ­ troductory words before this perform ance, th e first p a rt of which was the “Prologue in H eaven” from G oethe’s Faust. Dr. Steiner stood in front of the closed c u rta in som ew hat to the right of the center of the stage. As he spoke, there was a m om ent of tension, of danger, w hen suddenly in the center a n d front of the stage, a n d directly to the left of D r. Steiner as seen from the audience, the big tra p door opened in the floor. O ut of this, d u rin g the perform ance, M ephisto was to rise in the “Prologue in H eav en .” Dr. Steiner seem ed to be unaw are of the sudden deep, gaping hole right next to him . Luckily, young G raf von Polzer-H oditz h a d the presence of m ind to ju m p up onto the stage, take hold of D r. Steiner’s arm a n d lead him away from the d an g er spot. D r. Steiner seem ed to be astonished a t this sudden action, b u t as he looked to the side, he m ust have seen in w hat danger he h a d been. Two steps to the side, a n d he would have fallen into the gaping hole. He continued his introduction w ithout interruption. T he perform ance itself, on the great G oetheanum stage, was beautiful beyond words. T h e “Prologue in H eaven,” surrounded by the twelve carved pillars and the paintings above in the sm all dom e — it was really heaven. A t eight o’clock, New Y ear’s Eve, Dr. Steiner gave a lecture, T he Spiritual C om m union o f M a n kin d , in the g reat hall of the G oetheanum . T his was strictly a m em bers’ lecture. O ne h a d to be eighteen years old to becom e a m em ber, a n d since my friend an d I were lacking one year, we did n o t a tten d . I n ­ 71 stead, a group o f us young people m et at the Villa Duldeck, the hom e of Dr. Grosheintz, which Dr. Steiner h ad designed, an d we decided to stay up till m idnight for a New Y ear’s Eve party. I lived, with the friend who h ad invited m e, in a room in the house of a fam ily down the hill in D ornach-B rugg. At aro u n d h alf past nine o ’clock, we walked past the G oetheanum where we m et the night w atchm an with his G erm an shepherd w atchdog m aking the rounds. W e greeted one another; everything was peaceful a n d quiet as we walked down the hill to tell our landlord th a t we would not get hom e till after m id ­ night. T h e n we tu rn e d aro u n d a n d started back up the hill. W hen we were halfway up to the G oetheanum , a lady cam e ru n n in g tow ard us, calling out: “T h e G oetheanum is on fire!” W e could not believe our ears b u t ran up the hill as fast as we could. Grey smoke was pouring out of the u p p e r windows of the south wing o f the G oetheanum and craw ling like snakes over the silvery slate roof. It was about ten o’clock at night by then. T h e re were calls for w ater, so we joined a chain of helpers, filling the buckets in the Schreinerei a n d han d in g them along the line. O h, how slowly the w ater ran out of the faucet. T h e n there were calls from the terrace: “Bring ladders!” T here were a few ladders lying near the Schreinerei. I g rab b ed one an d rushed w ith it as fast as I could through the south p ortal a n d up the concrete stairs th a t led to the stage a n d dressing rooms. I could not get very far, for the space was filled with tra n sp a re n t, greenish smoke which m ade b rea th in g impossible. I started to cough an d could have suf­ focated. A Russian eurythm ist cam e ru n n in g after m e and pulled m e down the stairs. I h ad to ab an d o n the ladder. In the m eantim e the firem en an d fire engines from D ornach h a d arrived. D r. Steiner gave the ord er th a t everybody should leave the G oetheanum . T h e firem en took over. W e were asked to fetch vinegar to help the m en who h a d suffered from smoke inhalation. So a friend a n d I ra n down to H aus Eckinger and brought u p w hat vinegar we could find there for the first aid station which F rau Kolisko h a d p u t u p in the m eadow near H aus de Jaager. 72 T h e clouds of smoke becam e thicker an d thicker as they craw led now over b o th cupolas. O ne could h ear the crackling of the fire, b u t no flam es were visible. T h e G oetheanum h ad double walls, an inner a n d outer wall w ith air space betw een them . T h e two cupolas also were double — an inner one on which were the paintings, a n d an o u ter one covered with silvery N orw egian slate. T h ere was quite a bit of space b e­ tween them . T h ro u g h this space, betw een th e walls a n d b e ­ tween the domes, the fire ate its way. O ne could n o t see it from outside. Suddenly, as the ch u rch bells o f D ornach a n d A rlesheim pealed the h our of m idnight a n d ra n g in th e New Y ear, a trem endous flam e b urst fo rth w here the two dom es m et. Now it was clear th a t there was no help. Piece by piece, the large and the small dom e collapsed. Now the firem en directed the stream s of w ater onto the Schreinerei, the carp en try shop. T h e heat was trem endous. T h e w ater rose up as steam from the roof. W e carried out all the books from the bookstore, w hich was in one wing of the Schreinerei, down into H aus de Jaag er. W e m an ag ed loads we w ould not have been able to carry u n d er ordinary circum stances. A nd there, near his studio which contained his g reat wooden sculpture — the Christ betw een Lucifer an d A hrim an — stood Dr. Steiner gazing into the raging fire, on his rig h t Miss M aryon, the sculptress, on his left F raeulein W aller (later Mrs. Pyle). I stood quite n e a r to them as som eone cam e r u n ­ ning up to Dr. Steiner a n d told him th a t some m em bers were trying to move the C hrist statue from his studio out onto the m eadow behind the Schreinerei. Dr. Steiner said th a t should not be done a n d sent F raeulein W aller to give the message. She cam e too late; they h a d already m oved the statue. T h e fire m ade its m urderous progress. First the two dom es collapsed; then the walls were swallowed by the flam es, the big windows m elting in the trem endous h eat. T h e n the n o rth and south wings caved in; the west w ing was the last to go. W hen the flam es engulfed the organ pipes located in the west of the g reat hall, they responded w ith strange m usical sounds. T h e 73 flam es took on all m an n e r of colors as they m elted the great m etal pipes. Now n othing rem ained but two circles: one of fourteen col­ um ns, the other of twelve. They stood like flam ing torches in the black night sky, a sight both of h orror and beauty. O ne by one they fell over into the concrete substructure where the fire continued to b u rn for two m ore days. T hick smoke rose above the flam es. “It cannot be!” we said to ourselves as we gazed at the billowing smoke above the con­ crete foundation. “Surely, the smoke will clear away and the G oetheanum will be there in all its b e a u ty .” Alas, there before us was only gaping, physical nothingness. T h e Schreinerei was saved th ro u g h the efforts of the firem en. B ut the w ater h ad flooded the room s behind the stage, an d now the floors h a d to be dried, for Dr. Steiner h ad asked th a t the Conference go on as scheduled for New Y ear’s Day, in the Schreinerei: a t 5 P .M ., the Three Kings Play, a t 8 P .M ., his lecture in the series on T he B irth o f N atural Science. Everybody helped to get the Schreinerei ready for the five o’clock perform ance, which then took place as scheduled, while over at the G oetheanum site the fire was still flam ing. T h e c u rta in of the Schreinerei stage opened; the Angel, played by In a S chuurm an, stepped forw ard and, speaking the first words of greeting in the A ustrian dialect of the plays, “I tritt herei an oilen spot, a sehen g u a tn abend geb eng G od” (“I enter here joyfully an d bid you from God a beautiful good evening”), her voice failed her, an d she fought back her tears. A fter a short struggle, she gained the victory over the pain th a t gripped the hearts of all o f us who h a d experienced this terrible night, this u n h e a rd -o f disaster; she ended h er speech an d the play w ent on w ithout m ishap. For D r. Steiner’s lecture at eight o’clock the audience had assem bled early a n d sat in the Schreinerei hall in com plete silence, w aiting for him . If, on other occasions, one h ad seen him w alking up the G oetheanum hill, one was im pressed by his light a n d forw ard-striving step. O ne m ight call it an iam bic step — w ithout heaviness. Dr. Steiner a n d F rau D oktor h a d a room b eh in d th e Schreinerei stage; a n d now, as we all 74 sat there in silence, w aiting, we h e a rd heavy steps a p ­ proaching, the feet dragging; a n d D r. Steiner en tered th ro u g h the blue c u rta in beside the stage a n d stepped to the speaker’s desk. W e all rose an d stood in reverence before this great a n d beloved h u m an being. Dr. Steiner, w ith a voice of deepest sadness, as one m ortally w ounded, spoke a few sentences ab o u t the g reat loss we h a d experienced: “Das liebe G oetheanum , zehn Jahre A rb eit" (“T h e dear G oetheanum , ten years of w ork”), a n d then, w ith un b ro k en strength, he gave his lecture. A year later, in his lecture of D ecem ber 31, 1923, Dr. Steiner said th a t in the flam es of th e b u rn in g tem ple of A rtem is a t Ephesus one could rea d th e envy o f the Gods; in the flam es of the b u rn in g G oetheanum one could rea d the envy of h u m an beings. — T h ere rem ains w ith m e as precious m em ories the lunches at the house of Emil a n d B erta M olt, a t w hich R udolf Steiner an d M arie Steiner were present an d I was allowed to p a r ­ ticipate. Dr. Steiner wished a joyful m ood to prevail d u rin g m ealtim es, a n d while dessert was served, he frequently told jokes. It was in F ebruary, 1924, th a t R udolf Steiner a n d M arie Steiner cam e to lunch at H aus M olt for the last tim e. T h e lively conversation h a d tu rn e d to autom obiles a n d to H enry Ford, a n d R udolf Steiner said th a t he liked to ride in a Ford car (it was the “M odel T ” of th a t tim e). H e continued: “H enry Ford has just published his m em oirs,” a n d jokingly he added: “M any people have ‘m em oiritis’ now adays,” u p o n w hich M arie Steiner rem arked: “T h a t can be said of you, to o ,” for R udolf Steiner was at th a t tim e w riting his autobiography w hich a p ­ peared, week after week, in the periodical Das G oetheanum . As F rau D oktor m ade this rem ark, Dr. Steiner’s facial expres­ sion changed to deep seriousness. H e looked up, his black eyes seem ed to gaze into far distances, an d he said w ith his deep and resounding, w arm voice, very slowly: “Ja, es soll n u r schlicht u n d wahr sein." (“Yes, b u t it m ust be only sim ple an d tru e .”) A fter a short pause, Emil M olt said: “O ne ought to w rite F rau D oktor’s biography, to o .” W hereupon D r. Steiner replied: “Das ka n n m an j a nicht. Frau D oktor ist ein 75 kosmisches Wesen.” (“T h a t cannot be done. Frau D oktor is a cosmic b e in g .”)* T h e last tim e I saw R udolf Steiner, he was lying on his death b ed in his studio in the Schreinerei at the G oetheanum , at the feet of the C hrist statue which he him self h ad carved. T h e soft candle light threw a golden glow over his beloved countenance, w hich bore the expression o f greatest love as though he were going to open his eyes any m om ent a n d u tte r words o f kindness. T h e fragrance o f countless flowers pervaded the room . A m ong them was a w reath fashioned of every im ­ aginable flower from g ard en a n d m eadow sent by the children of th e W ald o rf School who h a d lost their greatest teacher a n d friend w hom they loved like a father. A nother w reath o f red roses, sent by A lbert Steffen, bore the inscription: D em G ottesfreund u n d M enschheitsfuehrer R u d o lf Steiner (T o the Friend o f G od a n d L eader of M ankind, R udolf Steiner). A g reat n u m b er of people h a d g a th e red for the crem ation a t the cem etery in Basel. Only few found room inside the crem atorium , w hich was a m u ch sm aller building th a n the present one. Most people h a d to stan d outside d u rin g the funeral service, am ong them my m other a n d myself. T h rough the open door one could h e a r clearly w hat went on inside. First there sounded the funeral m usic com posed by J a n Stuten. T h e n D r. R ittelm eyer carried out the funeral service. A fter th a t A lbert Steffen spoke, a n d m usic concluded the service. As M arie Steiner, A lbert Steffen, Dr. W egm ann, Dr. V reede, a n d Dr. W achsm uth left the crem atorium a n d cam e down the steps, the smoke began to rise from the chim ney. T h e spring sun rad iated , a n d suddenly there ap p eared a flock of white birds: it rose in spirals w ith the smoke a n d disappeared into the blue of the heavens. *This is an authentic memory. O ne m ust, however, be careful how one in ­ terprets such a rem ark and consider that there are m any aspects of the h um an individuality, especially in those most spiritually active. 76 E D U C A T IN G AS A N A R T : The R u d o lf Steiner M ethod, E dited by E kkehard Piening a n d N ick Lyons; available d ire c t­ ly from T h e R udolf Steiner School, 15 East 79 St., New York, N .Y .; $7.95. If the beginning of R udolf Steiner ed u cation in A m erica in New York City seem ed like a pioneering b reak th ro u g h in 1928, it seems even m ore so in this o u tstan d in g F iftieth Anniversary publication. How refreshing an d inspiring to read these pieces by teachers an d form er teachers. As H enry B arnes explains in his introduction, this collection does not p rete n d to be system atic or exhaustive, b u t each article describes a facet of life an d work in a R udolf Steiner school, “an d thus it is hoped th a t together they will form a m osaic of experience a n d thus serve to com m em orate the first fifty years of pioneer enterprise in this educational fie ld .” W hen so m uch is falling a p a rt, w hen so m any teachers in public a n d private schools have succum bed to cynicism an d opportunism , it is h earten in g to h e a r these faithful voices, building stone by stone a new cu ltu re in o u r m idst: “an e d u c a ­ tion th a t w ould nourish th e spiritual a n d artistic sides of a child’s n a tu re , as well as school his intellect a n d tra in his technical skills.” W hy is it th a t this rem arkable educational a rt is still so little known an d practiced, in a p eriod o f expanding n atio n al in ­ terest in artistic expression a n d alternative schooling? Barnes suggests th a t it is because the ed u cation rests on a pictu re of the total h u m a n being, soul a n d spirit a n d body, a n d this not in a vague religious way, b u t concretely. T h e know ledge on w hich the ed u cation is based comes from a spiritual scientific approach, which has evolved o ut o f the objective disciplines of n a tu ra l science. It is a frontier. T h e wholistic tem p er of the Steiner schools is gradually a t­ tra c tin g m ore interest, a n d th e years of practical work in agriculture, m edicine, n u tritio n , arch itectu re, curative e d u c a ­ tion for the h an d icap p ed , com m unity building, a n d th e arts, as well as education, are gradually providing g ro u n d for trust 77 on the p a rt of people who are searching for wholeness in themselves a n d in the world. T h e 28 individual articles in this book present ideas and m ethods w hich are not only education-transform ing b u t person-transform ing a n d w orld-transform ing. T h e book begins w ith a strong inform ative in troduction by H enry Barnes, history teacher a n d faculty c h airm an of the New York school for 30 years. This is followed by an astute piece by Barnes and Lyons on “E ducation as an A rt,” an im aginative picture of the “golden windows” o f the elem entary years by V irginia Paulsen, a n insightful account by V irginia Sease of th e Class T eacher, “Seeds of Science” for preschoolers by M argaret de Ris, R udolf C opple on Norse Myths in the F ifth G rade, an d a play by B a r­ b a ra Francis showing how a teacher m ay brin g alive the con­ tent o f a lesson for the children a n d herself. T h e n follow a w onderful th ird piece by H enry Barnes on the a rt of reading a n d an o th er on the d ram a tic a rt of H istory T eaching, two pieces by Christy Barnes on Speech an d Poetry an d on the Schooling o f Im agination th ro u g h L iteratu re a n d Com position, a n d a “m oving” account by K ari von O rd t of some aspects of Eurythm y. Franceschelli’s piece on m a th a n d geom etry is a plea for “appreciative th in k in g .” H ans G ebert writes on H igh School Physics a n d Chem istry, Rosem ary G ebert on H andw ork, M argaret F roehlich on Crafts, Je an Zay in a pow erful b rief piece on p ain tin g in the curriculum , a n d four delightful excur­ sions into story a n d playlet a n d poem as introducing arithm etic to the small children. D orothy H a rre r on Fairy T ales an d Square N um bers, N an ette G rim m on Discipline, a n d L ona Koch on the social ed u cation of four-year-olds, these are gems. George Rose of the A delphi W ald o rf faculty gives a substantial account of m usic curriculum a n d th e strong p ro ­ g ram a t his school. Jo h n G a rd n er’s piece, “Y outh Longs to K now ,” states the longing in ou r tim e for im m ediacy of experience, for m eaning th a t transcends conventional goals a n d routines, a n d for feel­ ing oneself a p a rt of an essential g ro u n d o f Being. W hen these longings are fru strated , he says, they m ay tu rn into despairing 78 an d destructive behaviors. H e describes the support th a t youth can get for its energies an d idealism from a schooling based on living experience, a n d a free individual p a rticip a tio n w ith the divine. “It was Steiner’s view th a t o u r present age begins som ething new in the history of m a n k in d .” Seeds of this renew al are found in T h o re a u , Em erson, W h itm a n , H aw thorne. In a piece called “E ducation as an A rt,” B arnes a n d Lyons write th a t the goal of artistic m eth o d in R udolf Steiner e d u c a ­ tions is to w aken the living concept w hich m ay becom e h u m an capacity. It comes ab o u t th ro u g h a rhythm ic sequence of perception, experience, understan d in g , b o th in each lesson a n d in the developm ent of the curriculum . T h e intelligence of the child is gradually led a n d encouraged a n d stren g th en ed from its early m anifestations in action and will, to the elem entary years w here feeling is upperm ost, to the high school c u r­ riculum w hich reflects the grow ing independence of thinking. A lan H ow ard’s concluding piece on “T h e F u tu re of Know ledge” is an o th er voice in the positive read in g o f the spiritual tasks of ed u cation in ou r tim e. Knowledge, he says, is the reu n itin g of the being o f m an an d the Being o f the world. T his is love, too, an d “relig io n .” A n ideal, yes, b u t, as he says, perhaps approp riately evoked in a book celebrating the Fiftieth Anniversary o f a school d edicated to “a living science, a living a rt a n d a living religion.” T his book is rich a n d readable. Its im aginative a n d m oral force sweetens the air w ith th e unm istakable scent of healthy an d grow ing form s. I hope it will be widely rea d in the b ro ad er ed ucational com m unity. M. C. R ichards 79 T E A C H IN G AS A LIV ELY A R T , by M arjorie Spock; T h e A nthroposophic Press, 1978; 138 pages; $3.95. It is no small feat to describe the b rea d th an d d e p th of the elem entary school curriculum b u ilt aro u n d the. developm ental stages of the child a n d em ployed since 1920, in its essential features, in a n ever increasing n u m b er of W ald o rf or R udolf Steiner schools aro u n d the w orld. M arjorie Spock has ac­ com plished this by fram ing the actu al description of the in te r­ related curriculum subjects, tau g h t from grade one th rough eight, w ith a n opening ch ap ter on “A New Picture of the H u m an B eing” w hich attem pts to explain the underlying philosophy of teaching, a n d three concluding chapters dealing w ith the child’s tem p eram en tal disposition, the tea c h e r’s role an d his relationship to the grow ing child. Miss Spock is herself an exam ple of the “lively a rt” of ex­ pression. R eaders who m ight well lay aside an o th er book will be led on from page to page a n d be a ttra c te d to the education she describes by her very read ab le a n d c h arm in g style. It is regrettable th a t the book does not contain a note on the au th o r, giving tim e, place a n d circum stances of her involve­ m en t w ith W ald o rf E ducation. A few words here will supply some background. A fter study­ ing eurythm y in D ornach, Sw itzerland, she tau g h t it to children in the New York R u d o lf Steiner School a n d the W ald o rf School in G arden City d u rin g their early years. L ater she ta u g h t grades b o th in the D alton School in New York City a n d in th e Fieldston School. T his book was first w ritten for her m aster’s thesis a t T eachers College, C olum bia University, in 1944, when it was seriously considered for publication there. She has p racticed bio-dynam ic g ard en in g in L ong Island an d in M aine, w here she is still ru n n in g a farm . She is the sister of th e well-known B enjam in Spock. It is the beauty of R udolf Steiner’s indications for the teaching of the various subjects th a t they are precise in term s of aim s, m ethods a n d long-range effects. T h e m any exam ples a n d situations described w ith considerable insight in the m id ­ dle chapters o f the book nevertheless should not be taken as 80 recipes th a t prevent a teacher from responding creatively to the changing needs of children today in any given location. R a th e r they should be taken as illustrations of the m any aspects of elem entary education offered in a W ald o rf School. T h e teach er’s resourcefulness, im agination an d co n tem ­ porariness are called u p o n a t all tim es to find ways of im ­ plem enting the indications in a m eaningful, diversified way in each school, in each class, today. T his friendly little volum e presents a rich, colorful p a n o ra m a o f the landscape of childhood’s m iddle years, only gently implying, perhaps, the existence o f deeper roots u n d ern eath , a n d w ithout seeking to b are them for the present. T h e sparkling p icture should not b lind us, of course, to the fact th a t all teaching is fra u g h t w ith problem s an d obstacles w hich will challenge the teachers in m any ways. T h e book m ay well be placed, w ith some explanatory rem arks such as those of the previous p a ra g ra p h , in the hands of in q uiring parents who seriously seek a viable alternative education for their children. Erika V. A sten C u r e — AN ANECDOTE* by H ein z Frankfurt A m other was troubled ab o u t her child; he bored into his nose insatiably. T h e little nose was already raw a n d th re a te n e d to becom e deform ed. W h a t could she do? She h u rried to R udolf Steiner. Lovingly he took the little boy on his arm a n d carried him to the eurythm ists who were just then having a recess from their rehearsal. “Just look a t this lovely blue lady!” — “Blue lad y ,” the child said after him . A nd R udolf Steiner w ent on: “A nd look a t this lovely yellow lad y ,” — “Lovely yellow la d y ,” the child repeated. A nd so the red, the green a n d the lilac lovely ladies were all adm ired a n d w ondered at. T h e n suddenly R udolf Steiner added, “A nd n o t one of them bores into her nose!” A t these words, the child pulled his little finger quickly out of his nose. A nd lovely lady A unt Kisseleff claim ed th a t from then on he was cured. *From M itteilungen, S tuttgart, G erm any; Easter 1978. 81 P IL G R IM A G E T O T H E T R E E OF LIFE by A lbert Steffen, Adonis Press, second p rin tin g 1978, 66 p p ., $3.95. Cover design by the au th o r. W e can be grateful for the rep rin tin g of this rem arkable little book in a new a n d ap p ealing edition. It is one to rea d again a n d again, m editatively, a n d is for all those who “long for a tru e perception of n a tu r e .” T h e serious student of h er rhythm s a n d form s will recognize m uch fam iliar a n d well-loved terrain , b u t it is likely th a t all will find themselves led tow ard new and ever w idening realm s of experience. T o perceive n a tu re truly, one m ust begin by w orking upon oneself — b a d habits m ust be recognized a n d dealt with. P u ri­ ty a n d freedom are thus the first qualifications. T h e various “types” which one m eets in the outdoors, all considering themselves friends of n a tu re , are deftly described: the one out for a ta n or to please the ladies, the one lost in m em ories, the one who looks a t a tree as so m any b o a rd feet o f lum ber. Yet all econom ic, personal, o r purely recreational reasons for “e n ­ joying” n a tu re m ust vanish, be p u rg ed away, if we are to becom e sufficiently receptive to h e a r h er speak. O ne who w ould observe n a tu re a n d appreciate her infinite a n d subtle transform ations m ust also move inw ardly — in the inner reaches o f the soul — in a realm of self-observation a n d self­ transform ation. A change in o u r habits will of itself bring ab o u t a “refinem ent o f the feelings.” Love is essential — “W h a t is already present in love, the longing to know, will lead m e o f itself to know ledge.” T o learn som ething new ab o u t a tree, one m ust “perfect oneself in love.” T h ro u g h Steffen’s m agic we see the inner w orld o f feelings as a c o u n te rp art to the vast w orld o f n a tu re . W hen a new and “friendly” feeling m anifests in the g ard en of the soul, it m ust be carefully ten d ed so th a t it m ay take root. C ultivation is necessary. T h a t w hich th reaten s it — ugliness a n d stupidity — m ust be reg ard ed as poor soil, or as a b o m b ard m en t by hailstones. T h e lab o r is never-ending, as all gardeners know. If a m an is to rise to a tru e perception of the blue sky or a b u d ­ 82 ding m eadow , he m ust lab o r to reproduce the p icture w ithin himself. “All this requires th a t the inner life be m ore steadfast yet sensitive, richer in love a n d m ore soaring.” T h e perception of n a tu re “requires m any varied a n d delicate nuances of seeing a n d feeling. T h e soul m ust transform itself for the sake of a m eadow which puts forth its first b lo o m .” T h a t w hich lives as the artist in m an , his creative and im aginative capacities, m ust thus be exercised to respond to the artist in n atu re. Steffen speaks of being “creators” of our own feelings. H ere we have help and insight into the creative process, led by one who knows it well. O nce again we see th a t the act of creating involves first a clearing-aw ay of obstacles, of developing sensitivity, an d th en a “letting arise,” a n activity of stillness, o f restraint, o f objectivity. T hus we are led beyond w hat we usually call G oetheanistic observation, in which we strive for a living picture of the whole, for an Im agination. Now we are entering the world of Inspiration. T h e first essay, “T h e P re p a ra tio n ,” lays the groundw ork for a new perception o f n a tu re and gives us the rules we m ust follow. T h e second essay, “T h e W ay ,” is divided into three parts, an d leads us into a new w orld. H ere we m eet new perceptions, new feelings, new revelations. It is in these latte r essays th a t the poems ap p ear, for such experiences can best be com m unicated th rough art. O ne feels th a t it is the poet in p a rticu la r who m ust tra in his powers of observation, who perhaps best bridges the transform ation into the inner response o f the soul. This translation by E leanor Trives, w hich so beautifully em bodies the pace and poetic im pact of the original, first a p ­ peared in 1943. May it now becom e know n an d loved by a whole new generation! T h e volum e has a lively feel. T h e cover, bearing Steffen’s m o tif from A le x a n d e r’s Transform ation, is striking. O ne regrets the inevitable loss w hen poems are translated into an o th er language, b u t again in this new edition the G erm an originals of Steffen’s poems ap p earin g in the text are g ath ered together in a separate section at the end. 83 Pilgrimage to the Tree o f L ife is a book to live with through the years. No teacher should be w ithout it. “In our day it is chiefly the science of the tree th a t is ta u g h t,” says A lbert Stef­ fen. “Knowledge, however, sprang from love. T herefore I w ould prefer th a t som eone tell m e how to learn to love trees.” Jeanne Bergen T H E L IV IN G E A R T H — T h e O rganic O rigin o f Rocks and M inerals by W alth er Cloos; translated by K. Castelliz and B. Saunders-Davies from Lebensstufen der E rd e , L an th o rn Press, 1978, 160 p p ., 8 pp. half-tone illustrations, (£2.85). This book is a n am plification of certain statem ents by R udolf Steiner, m ainly in Occult Science, to the effect th a t the whole m ineral stru ctu re of the present E arth planet is an offcast of form er processes of life. T h e translators express the hope th a t it will be w elcom ed as a com panion to G ro h m an n ’s work on th e p lant, especially by teachers, a n d indeed the w ealth of detail given by W alth er Cloos appears to place it in this class. B ut to am plify is not necessarily to increase our understanding, a n d Cloos does not atte m p t to explain w hat Steiner m eans by these statem ents about the m ineral E a rth in term s th a t we can reconcile w ith our own experience. Steiner’s statem ents were based on his readings in the Akashic Record, an occult phenom enon he said was accessible to all those who follow a certain p a th of tra in in g w hich he described in detail. Steiner evidently expected others to follow this p a th to the extent of being able to rep eat and confirm his own readings, b u t he also hoped th a t his occult findings would be confirm ed less directly, though no less certainly, by the m ore usual kind of scientific observation. I do not have access to the Akashic C hronicle myself, a n d Cloos m akes no m ention of it, so the direct m eth o d of confirm ation is not available for discussion; b u t I do believe th a t we should take Steiner with enough seriousness to give his second m ethod a fair trial, and 84 use rigorous logical thinking a n d unbiassed observation to try to find out w hat he m ean t us to u n d erstan d by a living and dying planet. P erhaps this is w hat Cloos set out to a ttem p t, b u t I am not sure th at he has seen the n a tu re of the problem . W hat we know as life is a property of living organism s; these are bodies th a t have the power to reproduce their kind an d to develop a n d m a in ta in their characteristic form s by assim ilating an d converting n u trie n t m aterial. W e are asked to consider th a t the planet E a rth is or was such an organism . Yet Cloos seems to be confused ab o u t the n a tu re of a n organism a n d about life processes. He m akes the analogy betw een the m ineral E arth and a corpse, b u t writes as if a living p la n t or anim al were subject to living forces alone a n d only becomes subject to physical forces when dead; in fact, any organism w ith a physical body is subject to physical forces at all times. It is gravity th a t ensures th a t a p la n t grows u p straight; it is the law of conservation of energy th a t enables a p red a to r to h u n t an d the law of inertia th a t m akes possible the flight of the swallow. Those physical forces th a t produce the crystals and gemstones also enable us to chew ou r food an d see distant objects. Those forces peculiar to living organism s — the ethereal form ative forces of w hich Steiner speaks — th a t enable a p la n t or anim al to assim ilate food into its own specific life-form , are ad d itio n al to the physical forces acting on the organism . If the E a rth is a n organism , we m ust ask w hat is its specific life-form (leaving aside the question of reproduction) and how is it m ain tain ed . O therw ise there is no point in talking ab o u t life processes. Cloos m erely illustrates some resem blances betw een m inerals a n d living form s, such as a folded rock th a t looks a bit like tree b ark or twisted wood, a n d th e lovely flower-like an d frond-shaped crystals, a n d assumes th a t since flowers, fronds a n d b ark are pro d u ced by living organism s, the o th er form s m ust also be the result of life processes. O thers, n o tin g the sim ilarities, have argued th a t, w here the resem blance is m ore th a n superficial a n d really depends u p o n the w orking of sim ilar forces, this is evidence th a t physical forces are also at work in the living kingdom s. O f course, if Cloos m eans th a t 85 any force at work in a living organism is a life force, then his definition of a life force m ust becom e so vague as to lose any distinction betw een living a n d physical, an d we are arguing only about term inology. But then w hat becomes of Steiner’s exciting concept of the E a rth plan et as a n organism ? Surely Steiner deserves b e tte r th an this. In the realm of straightforw ard geology, Cloos still seems ra th e r confused. H e outlines three b ro ad groups of rocks: a prim al layer of g ran u la r rock such as granite; an interm ediate layer of foliated schists, slates and shales; a n d the m ost recent layer mostly m ade u p of thick beds of lim estone. Such a schem e m ight have been found in a nineteenth-century prim er, b u t it hardly fits the facts as we know them today. Cloos him self has to adm it th a t there are limestones am ongst the m ost ancient rocks, thus shaking the structure of his schem e; he avoids the fact th a t granite is never found as a basal layer b u t always as an intrusion into still older sedim en­ tary rocks. It m ay well be th a t the whole process of granitization, by which vast masses of continental crust becom e transform ed into crystalline rock (such as granite) w ith a broad m arg in of more-or-less m etam orphosed rocks (such as schist an d slate) is one o f the m ore recent developm ents in the E a rth ’s long history, a n d it w ould seem to m e th a t this fits m uch better w ith S teiner’s idea th a t the m ineral phase is the last step in the form ation of ou r planet. T h e e a rth sciences have m ade great progress since Steiner’s tim e, b u t Cloos treats scientists w ith derision. H e repeats the hoary jibe th a t com pares a geologist w ith a m an who observes a p a tie n t’s pulse over one year an d then projects the pulse-rate for 300 years forw ards an d backw ards w ithout realizing th a t the p a tie n t does not live th a t long. In fact scientists are always careful to describe th eir observations, their assum ptions and their calculations in such a way th a t others can check them , whereas Cloos can only rep eat dogm atically w hat Steiner has p u t forw ard. If Cloos wishes to im pute stupidity to scientists, he should be careful th at his own naivety does not bring discredit upon Steiner. It seems to m e th a t the m odern scien­ tific picture of the e a rth planet as a totality, w ith its exciting 86 new concepts of plate tectonics a n d sub-crustal circulations, is m uch closer to Steiner’s view of the e a rth as a kind of gigantic developing em bryo th a n is the m u d d le d schem e o u tlined by Cloos. T h e translators say th a t this book should be helpful to teachers in W aldorf schools, b u t here again I think a word of caution necessary. Steiner com m ended G oethe’s work in the field of science as a m odel for scientific study in schools, based as it was on close but w ide-ranging observation of phenom ena free from preconceived abstract theories. G oethe him self m ade a characteristic co n trib u tio n to geological know ledge by postulating w idespread glaciation over E urope a t a form er tim e an ice-age — based on his observation of Scandinavian-type boulders in G erm any a n d the perception th at a glacier was the only n a tu ra l phenom enon capable of m oving such large rocks so far. In fact, the m odern picture of E a rth ’s history is based on ju st such G oethe-like science, p a tie n t an d open-m inded; Cloos, however, w arns against trying to explain the past from the present, b u t offers no alternative except his own, Steiner-derived preconceptions. W hether one agrees w ith his in terp retatio n s of Steiner or not, this is hardly the best exam ple of scientific procedure to place before young people. Finally, I would like to suggest th a t the translators’ work has not been wasted, in spite of the serious shortcom ings of the book as a work of science. T h ere is a splendid poetry of tru th in Steiner’s work, an d it is an excellent thing to be rem inded of all th a t he has p u t forw ard concerning the origins of our m ineral planet. T h e re are still m ore questions th a n answers, b u t Cloos has b ro u g h t together, a n d the translators an d publisher have m ade available to the English-speaking w orld, a com pact basketful of rocky problem s to po n d er over. May it be used wisely. R a lp h B rocklebank 87 CONTRIBUTORS TO TH IS ISSUE ALAN H O W A R D — R etired W aldorf teacher who has lectured widely on R udolf Steiner an d his work. • M. C. (Mary Caroline) RICHARDS — Poet, potter, free lance teacher and lecturer; au th o r of Centering: in P o t­ tery, a nd the Person; translator: The T heater and its D ouble by A rtaud. • M A R TIN KURKOW SKI — Form er high school student at the R udolf Steiner School, New York. • A L B E R T STEFFEN — Swiss poet, dram atist, novelist; president of the A nthroposophical Society, 1925-1963. • LAURA T A Y L O R — W ife of an English playwright of the last century. • DO NA LD H A LL — G raduate of the School of P ainting (Assenza) at the G oetheanum , D ornach, Switzerland; form er painting teacher at the R udolf Steiner School, Basel; resident artist at the R udolf Steiner Farm School, Harlem ville, N.Y. • AL LANEY — Free-lance journalist; form er sports w riter for the New York H erald T ribune; au th o r of Paris Herald: The Incredible N ewspaper and Covering the Courts. * CHRISTY BARNES — R etired English teacher at the R udolf Steiner School, New York; editor of A lb e rt Steffen, Translation an d T rib u te; Jo u rn ey m a n ’s A lm anac. • R U D O LF STE IN ER (1861-1925) In au g u rato r of A nthroposophy and the School for Spiritual Science, G oetheanum , D or­ nach, Switzerland. • KARL EGE — (1899-1973) T eacher, lecturer; tau g h t in the original W aldorf School an d the R udolf Steiner School, New York; consultant to a n um ber of schools in this country an d abroad; a founder of the R udolf Steiner Farm School, Harlem ville, N.Y. • HARRY KRETZ — T eacher, m usician; form erly a t the R udolf Steiner School, New York and C am p Glen Brook; presently at the R udolf Steiner Farm School, H arlem ville, N.Y. • HANS G EBERT — H igh school physics teacher at M ichael H all, E ngland for 16 years; head of Physics D epartm ent of B ir­ m ingham Polytechnic; Associate Professor an d Co-D irector of the W aldorf Institute of Mercy College, D etroit. • MARK T A PE R — Form er student of the R udolf Steiner School, New York. • ERIKA V. A STEN — Ph.D . in Musicology, Berlin; ten years in Public Broadcasting; form er class teacher, D etroit W aldorf School. • JEA N N E BERGEN — N aturalist; B icentennial Essay A w ard, 1976; faculty, R udolf Steiner F arm School, H arlem ville, N.Y. • R A LPH BROCKELBANK - M.A. in Geology, C am bridge, E ngland; chairm an of Color G roup of G reat B ritain; m em ber o f G oethean Science F oundation; adm inistrator of Sunfield School, Clent, E ngland. EDUCATION AS AN ART Published b y the W aldorf Schools in n o rth America S P R IN G 1979: Special double issue celebrating the 50th anniversary o f the in c e p tio n o f W a ld o rf E ducation on the N o rth A m erican continent. A R T IC L E S by L. Francis Edmunds, Alan Howard, Rene M. Q uerido, Betty Kane, Nick Lyons, Stephen Edelgtass, N anette G rim m , H elm ut Krause, and o thers. - G A L L E R Y OF P O R T R A IT S : th e W aldorf Schools and W aldorf Teacher T raining Institutes in N orth America Today. - W O RLD L IS T of Waldorf (Rudolf Steiner) Schools. - C O LO R PAG ES of the 50th Anniversary Exhibit. - G U E ST E D IT O R IA L by Henry Barnes. Double issue: $2.75. - Order from ANTHROPOSOPHIC PRESS, 258 Hungry Hollow Road, Spring Valley, N.Y. 10977; or from ST. GEORGE BOOK SERVICE, P.O. Box 225, Spring Valley, N.Y. 10977. 88 TEACHING AS A LIVELYART by MARJORIE SPOCK Here, at last, is a book on the W aldorf method of teach­ ing that w ill delight teachers, parents, students and every­ one else interested in a living approach to the education of our children. Marjorie Spock, a truly creative individual, is w ell-prepared to w rite such a book. First, she has a thor­ ough grasp of Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophy, which is es­ sential to an understanding of his views on education. She is also a teacher of long experience, a eurythmist, and the author of numerous essays and articles on education. In Teaching as a Lively Art, Miss Spock devotes a chap­ ter to each of the grades through high school, discussing problems and methods. The concluding chapters are di­ rected to parents and teachers. Paper, 144 pages, illustrated, $3.95 “ This book makes you want to send your child to a W aldorf School!” “ It w ill be of use to teachers as w ell as parents.” “ M arjorie Spock is a fine w riter and Teaching as a Lively A rt is an excellent example of her direct and lu cid style.” THE ANTHROPOSOPHIC PRESS 258 H ungry H ollow Road S pring Valley, New Y o rk 10977 Agents and distributors in the United States for RUDOLF STEINER PRESS, LONDON STEINER BOOK CENTRE, NORTH VANCOUVER 89 E m e r s o n C o lle g e A centre for adult education, training and research based on the w ork o f Rudolf Steiner. Foundation Year: Education Course: Agriculture Course: Centre for Social Development: Arts: A year of orientation and exploration in Anthroposophy. A one-year training course in W aldorf Education. Introduction to fundamentals of bio-dynamic agriculture and gardening. One-term and one-year courses of training in social questions and practice. Opportunities for further work in sculpture, painting or eurythmy, follow ing the Foundation Year or equivalent. For further information, please write to: The Secretary, Emerson College, Forest Row, Sussex RH18 5JX, England. hpsilud fA entoC acrm S 9 2 0 0 Fair Oaks Blvd. Fair Oaks. Calif. 9 5 6 2 8 RENE M. Q U E R ID O A D M IN IS T R A T O R F O U N D A T IO N Y E A R based on the w ork of in S P IR IT U A L S C IE N C E R U D O L F S T E IN E R T E A C H E R T R A IN IN G A P P R E N T IC E S H IP in cooperation with the Sacramento Waldorf School A M E R IC A N S T U D IE S P R O G R A M seeks to penetrate the spiritual reality of America in our time E U R Y T H M Y , S P E E C H , and D R A M A B IO D Y N A M IC G A R D E N IN G A P P R E N T IC E S H IP P R O G R A M Intensive study in full time and part time studies; public lectures. 90 which Waldorf Teacher Training THE WALDORF INSTITUTE OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA at H IG H L A N D HALL 17100 Superior Street N o rth rid g e, C a lifo rn ia 91324 offers a W aldorf Teaching Training Program from Mid-September to Mid-June. This intensive one-year Program is housed at H ighland Hall, a W aldorf School, w ith grades Nursery through Twelfth. For full details please send for our brochure. DIRECTORS D r. V ir g in ia Sease, a n d M r . John B rou sseau A training in Speech Formation by Sophia Walsh o f Dornach is also available during the Winter months. WALDORF INSTITUTE------------------OF MERCY COLLEGE------------------8469 East Jefferson, Detroit, Michigan 48214* offers four programs: • The ORIENTATION YEAR provides a firm basis in A n th roposophy w ith a p p ro p ria te em phasis o n arts, crafts a n d cognitive courses. It is a m ajor tow ards a B.A. D egree and o p en to g rad u ates an d u n d erg ra d u ates. a The TEACHER TRAINING program is designed to m e e t th e need s of W aldorf (Steiner) Schools a t th e elem en tary an d high school level. It also provides elem en tary certifi­ catio n by th e S tate of M ichigan if desired. T here is a n eed for W aldorf teachers. • The EARLY CH ILD H O O D EDUCATION program is o ffered in asso ciatio n with th e In tern atio n al A ssociation of W aldorf K indergartens. It is in te n d e d as training for w ork in nurseries an d k in d erg arten s an d for th o se co n cern ed w ith th e first seven years of life. • The SPECIAL (CURATIVE) EDUCATION p ro g ram is o ffe re d in a s so c ia tio n w ith th e Cam phill School (Beaver Run) an d th e E speranza School (Chicago). It leads to w ork in hom es an d schools for h an d ic a p p e d children. DIRECTORS: W erner Glas, Ph.D., H ans G ebert, R alph M arinelli A ccred ited by th e N orth C entral A ssociation of C olleges an d S econdary Schools 'A d d ress a fter July 1, 1979 ■ 23399 Evergreen Rd., Southfield, Mich. (A beautiful cam pus on 118 acres of land 15 m iles from dow ntow n Detroit) 91 the Toronto W ALDORF SCH O OL Kindergarten — Grade 12 9100 B athurst Street T h o rn h ill, O n tario L3T3N3, Canada B R IS T O L W A L D O R F S C H O O L Park Place, Clifton, Bristol 8 This School is now in its sixth year with over 200 pupils. It is firmly established on a central city site with im m ense potential. W e intend to develop besides a good W aldorf School, also a vitally needed Social Center involving parents and friends. In Septem ber 1980 an U pper School is being established. W e shall need Teachers for this work. Please write to us if you feel a response to the challenge of this pioneering work in England. Fern Hill Environs & P roperties Secluded homesites & properties in rural community; adjoining biodynamic farm, Waldorf School, woodlands, swimming, common lands. Ideal for families, retired persons or second home. Investment opportunity, write: Fern Hill Environs, Harlemville, Ghent, N.Y. 12075 call: 518-672-4815 D iaetpension VIGILIA A-6380 ST. JOHANN IN TIROL, AUSTRIA HEALTH FOODS - BIO-DYNAMIC FARM Train line from Dornach Tel. (0 53 52) 2256 92 A r i WALDORF BOARDING SCHOOL / \ r \-^ High Mowing School Wilton, New Hampshire We are a coeducational boarding school, beautifully situated in hilly, wooded country, about 65 miles northwest of Boston (Enrollment 100110; boarding, grades 9-12; day students, 7-12). Since our founding as a W aldorf School in 1942, we have prepared hundreds of students who have entered a wide variety of careers: gov­ ernment, business, medicine, education, and the arts and crafts. Quite a number of our alumni send us their sons and daughters to educate. We offer the following program: Academic Arts & Crafts Practical (4 years each of) English History Mathematics Science French German Drama Music Eurythmy Art Weaving Pottery Wood Carving Biodynamic Agriculture Forestry Carpentry Building Construction Motor Mechanics Sports are largely noncompetitive. Where possible, we raise our own food; and our kitchen serves nutritious, well balanced meals for both meat eaters and vegetarians. We are neither traditional nor “ free” in form. Students live and work within a definite educational and social structure and yet have freedom within the framework of expectations and requirements. The atmosphere is friendly, informal, and homelike. A capable and devoted faculty works closely to help each student find his own direction and purpose in life. HIGH MOWING SCHOOL, Abbot Hill Road, Wilton, N.H. 03086 Telephone (603) 654-2391 93 Kneippsan a torium Dr. Felbermayer Alpenpark and Ski-Station, A - 6793 Gashurn I Montafon VACATION — REST — REFRESHMENT — RECOVERY On the sunny slopes of the Austrian Alps 996 m e tre s a b o v e se a le ve l Treatment broadened by spiritual-scientifically oriented medicine. Health foods, biodynamically grown; Hydrotherapy (Kneipp, Sauna, Baths); Massage; Special diet; Thera­ peutic Gymnastics; Neuraltherapy. Chamber Music; Lectures. Open, mid-December to end of October. Tel. 00 43/ 55 58/ 2 18 WELEDA massage oil with Arnica At your Health Food Store Ask for our m ail order catalog Weleda Inc., 841 S. Main St., Spring Valley, N.Y. 10977 94 CAMPHILL VILLAGE Gift Shop H A N D C R A F T S Wooden cutting boards, trivets, toys Stuffed soft toys / Weavings / Batiks Enamel dishes, bowls, pendants Blank books covered in hand-woven material or batik Visit our store Chrysler Pond Road, Copake, N.Y. 12516 Tel.(518)329-4511. Open daily except Tuesdays. We also fill mail orders. Write for catalogue. 95 AN EV ID E N T NEED O F O U R TIMES by KARL EGE G o a ls o f E d u c a t io n a t t h e C lo s e o f th e C e n t u r y T he th o u g h ts o f a teacher on his w o rk and on the new needs confronting W aldorf Education. From the C ontents: In tro d u c tio n by A rvia Ege; The N a tu re o f U n d e rs ta n d in g ; P ro b le m s o f P u b e rty ; P ro s p e c ts fo r th e F u tu re ; T e a c h e r’ s P re p a ra tio n ; M u tu a l T ru s t. 66 pp., $3.50. P IL G R IM A G E T O THE TREE O F LIFE by ALBERT STEFFEN A b o o k to lead te a c h e rs , p a re n ts and n a tu re lovers back in to th e e x p e rie n c e s o f c h ild h o o d and fo rw a rd in to th e rid d le s o f th e life and d e a th fo rc e s at w o rk in th e w o rld . A p o e t’s s p iritu a l in s ig h t in to n a tu re and s e lf-d e v e lo p m e n t. A new e d itio n w ith co v e r design by the au th o r, $ 3 .9 5 . Please add 50$ for postage. A D O N I S P R E S S Hillsdale, New York 12529 ChildandMan ________Journal for Waldorf Education WINTER - SPRING 1979 R E L IG IO N & T H E S O C IA L T A S K O F SC H O O L S Has R e lig io n any Place in E d u c a tio n ? (part 1 ) ................................A la n H ow ard R e d is c o v e rin g th e Phases o f H um an L if e .......................... C h risto p h er Schaefer A Deep C o m m u n a l Im p u ls e (th e B ris to l S c h o o l).............................. Jo h n A ld e r W h e re a T e a c h e r's Road Can L e a d ..................................................R o n a ld Jarman SUMMER - MICHAELMAS 1979 M O V E M E N T IN SC H O O L S tru g g lin g w ith Chaos — W hy te a ch e v e ry th in g ? ....................Janet W illiam son Space is Hum an (Teaching B o th m e r G y m n a s tic s )........................ Paul M atthew s T h e S easons — My C u rric u lu m in C la s s T w o (part 2 ) .............. D ennis D em annet ...a n d m u c h m o r e ! 48 c o lo u r fu l pages, w ith th e la te st lis t o f (1 8 0 4 ) W a ld o rf S ch o o ls a ro u n d th e w orld. S ubscription $6 p er year p o stag e paid, or individual copies $4.50 from D iane Schm itt, 1823 Beech Street, W antagh, NY 11793 or from A nthroposophic Press, 358 Hungry Hollow Road, Spring Valley, NY 10977. 96 LEIERN Leier-M akers E D M U N D PRA CHT und L O T H A R G AERTNER 1926 1976 W . L O T H A R G AERTNER F O R IN F O R M A T IO N W R IT E T O D -7750 K O N S T A N Z / A . B . F ritz-A rnold-S trasse 18 / P o stfa ch 8905 W. G erm any T elephone 07531 / 61785 R u d o lf S te in e r F a rm S ch o o l S u m m e r P ro g ra m s f o r CHIL DRE N S u m m er at H aw thorne Valley Farm — A c re a tiv e su m m e r e x p e rie n c e fo r c h ild re n ages 9 - 12: fa rm ch o re s, s w im m in g , h ik in g , a rtis tic w o rk at H a w th o rn e V alley Farm . F o u r w e e ks, s ta rtin g Ju n e 30th. The Agaw am uck W ilderness Adventure — A c h a lle n g in g six w e e ks o f le a rn in g to live in h a rm o n y w ith na ture . B a ck p a c k in g , c a n o e in g , ro c k c lim b in g in th e B e rk s h ire s , C a ts k ills and A d iro n d a c k s . F o re s t e c o lo g y , s w im m in g , m u sic. A ge 13 and o ld e r. Six w e e ks, s ta rtin g Ju n e 30th. Write or phone: Rudolf Steiner Farm School, RD 2, Harlemville, Ghent, New York 12075 Tel. (518) 672-7120 weekdays until 4 o'clock ST AFF: Christy Barnes, E ditor; Jeanne Bergen, Sandra Sherman, Editorial Assistants; Janet Hutchinson, Subscriptions. Published twice a year by the Anthroposophical Society in America. S u bscriptions S6.00 per year. Back numbers may he obtained upon request from Journal for Anthroposophy, 211 Madison Avenue, New York, N .Y . 10016. Title Design by Walter Roggenkamp.