ФЕДЕРАЛЬНОЕ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННОЕ АВТОНОМНОЕ

ОБРАЗОВАТЕЛЬНОЕ УЧРЕЖДЕНИЕ ВЫСШЕГО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ

«КРЫМСКИЙ ФЕДЕРАЛЬНЫЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ

ИМЕНИ В. И. ВЕРНАДСКОГО»

К.А. Мележик

КУРС СОВРЕМЕННОГО ПРОФЕССИОНАЛЬНО-ОРИНТИРОВАННОГО

АНГЛИЙСКОГО ЯЗЫКА: УРОВНИ С-1/С-2

УЧЕБНИК

для обучающихся по основным профессиональным образовательным

программам магистратуры

Симферополь

2021

Рекомендовано к печати учебно-методическим советом Института филологии

(структурное подразделение) ФГАОУ ВО «Крымский федеральный университет

имени В. И. Вернадского» от «17» июня 2021 г., протокол № 3.

Рекомендовано к печати учебно-методическим советом ФГАОУ ВО

«Крымский федеральный университет имени В. И. Вернадского» от «17» июня 2021

г., протокол № 11.

Печатается по решению Ученого совета ФГАОУ ВО «Крымский федеральный

университет имени В. И. Вернадского» от «02» июля 2021 г., протокол № 12.

Рецензенты:

Петренко А.Д., д. филол. наук, профессор (ФГАОУ ВО «Крымский

федеральный университет имени В. И. Вернадского»)

Бухаров В.М., д. филол. наук, профессор (ФГБОУ ВО «Нижегородский

государственный лингвистический университет имени Н. А. Добролюбова»)

Мележик К.А. Сomprehending and analyzing domain-oriented texts. Курс

современного профессионально-ориентированного английского языка: уровни

С-1/С-2. Учебник на английском языке. — Симферополь, 2021. — 16 п.л.

Учебник предназначен будущим специалистам различных направлений для

развития умений и навыков междисциплинарной англоязычной коммуникации в

актуальных областях, представляющих не только специальный, но и общенаучный,

социально-культурный интерес. Это усовершенствованный курс предметноориентированного английского языка (ПОАЯ), как для аудиторного усвоения под

руководством преподавателя, так и для самостоятельного анализа и обработки специальной

литературы.

Учебник построен из 20 уроков, содержащих общенаучные тексты

междисциплинарной тематики, сопутствующие им упражнения и задания по развитию

навыков интенсивного и экстенсивного чтения, структурно-логического и лингвокультурного анализа, реферирования, аннотирования и презентации.

Каждый из 20 уроков включает текст для интенсивного чтения с преподавателем,

текст для самостоятельного экстенсивного чтения, инструкции по обработке текста и

контрольные задания. Тексты распределены по семи блокам междисциплинарной

тематики: 1. Транснациональный английский язык как инструмент глобализации; 2.

Межкультурная коммуникативная компетенция; 3. Глобализация системы образования; 4.

Средства массовой коммуникации; 5. Международные экономические отношения; 6.

Социальное, биологическое и экологическое многообразие мира; 7. Международный

туризм. В каждом уроке предусмотрено выполнение двух аннотаций, рефератов или

презентаций.

Учебник завершается грамматическим Приложением, предусматривающим

прагматический обзор морфосинтаксических трудностей, с которыми сталкиваются

будущие специалисты в устной и письменной общенаучной и профессиональной

коммуникации.

В учебнике содержатся рекомендации по работе с научной литературой, обработке и

поиску научной информации, реферированию и аннотированию. В каждом из уроков

имеются задания по закреплению материала и упражнения для развития коммуникативных

умений и навыков. Учебник рассчитан на 40-80 часов занятий с преподавателем и 80-160

часов самостоятельной работы.

© К.А. Мележик 2021

KARINA MELEZHIK

COMPREHENDING AND ANALYZING DOMAIN-ORIENTED

TEXTS

English for interdisciplinary studies

A manual for undergraduate and postgraduate university students

ПОЯСНИТЕЛЬНАЯ ЗАПИСКА

Цели и задачи совершенствования английского языка (АЯ) на заключительном, этапе

университетского курса совпадают с целями и задачами междисциплинарной подготовки и

профессионального становления специалиста, т.е. АЯ постигается как форма, в которую облекается

специальное знание, в соответствии с условиями межнационального общения.

В основу учебника положен междисциплинарный подход, который учитывает многообразие

современного мира, включая диверсификацию вариантов транснационального АЯ или «английских языков

мира», многообразие форматов межкультурной

коммуникации,

глобализацию образования,

многоплановость социально-экономических отношений, международный туризм, биологическое и

экологическое разнообразие, взаимодействие направлений научных исследований.

Принцип

междисциплинарности реализуется в переходе от стереотипов традиционного анализа текста к контентноязыковому интегрированному изучению АЯ (Content and Language Integrated Learning – CLIL) в предметноориентированном коммуникативном контексте, т. е. содержание учебника интегрируется в предметную

сферу последующей общенаучной и межкультурной коммуникации.

В поисках общей платформы, на которой можно объединить различные подходы к изучению деловой,

организационной и профессиональной коммуникации на АЯ, мы обращаемся к принятому в когнитивной

лингвистике понятию домена, который представляет собой сферу (интересов), поле (деятельности), область

(знаний) – а domain is a particular field of thought, activity, or interest, especially one over which someone has

control, influence, or rights [Computer Desktop Encyclopedia].

Фактически, тот АЯ, о котором идет речь, это язык, ориентированный на определенные предметные

области. Он предназначен для выполнения функций, связанных с обменом любой информацией: в бизнесе,

по месту работы, в организационной и профессиональной сфере, в коммуникации, отражающей предметные

области социально-культурного разнообразия современного общества. Для обозначения контактного АЯ

межнациональной коммуникации, отражающей любые специализированные домены социально-культурного

разнообразия современного общества, мы используем номинацию «предметно-ориентированный

английский язык (ПОАЯ)», domain-oriented English (DOE). ПОАЯ/DOE осуществляет функцию контактного

языка, обеспечивающего потребности межнациональной и межкультурной коммуникации, т.е. служит

универсальным языком-посредником для людей, разделяющих интересы в какой-либо предметной сфере,

но не имеющих общности родного языка и национальной культуры.

Структура коммуникации на ПОАЯ/DOE соответствует а) открытому институциональному уровню

межорганизационного взаимодействия, и б) уровню интеграции транснациональной организации в

локальных гражданских сообществах

С учетом многообразия вариантов АЯ, студенты должны не только владеть языком на достаточно высоком

уровне – С1/С2 Международной классификации языковой компетенции, но и иметь представление о

диапазоне его функционирования, что обусловливает необходимость изучения специфики

коммуникативных контекстов, предусматривающих его постоянное использование.

Предлагаемый учебный комплекс состоит из 20 уроков, содержащих по два общенаучных текста

междисциплинарной тематики, сопутствующие им упражнения и задания по развитию навыков

интенсивного и экстенсивного чтения, структурно-логического и лингво-культурного анализа,

реферирования, аннотирования и презентации.

Каждый из 20 уроков включает текст для интенсивного чтения с преподавателем, текст для

самостоятельного экстенсивного чтения, инструкции по обработке текста и контрольные задания. Тексты

распределены по семи блокам междисциплинарной тематики: 1. Транснациональный английский язык как

инструмент глобализации; 2. Межкультурная коммуникативная компетенция; 3. Глобализация системы

образования; 4. Средства массовой коммуникации; 5. Международные экономические отношения; 6.

Социальное, биологическое и экологическое многообразие мира; 7. Международный туризм. В каждом уроке

предусмотрено выполнение аннотаций, рефератов или презентаций.

В первой части каждого урока совершенствуются навыки просмотрового, ознакомительного и изучающего

чтения, которые требуют различной полноты и точности понимания текста. Задания и упражнения,

развивающие навыки интенсивного чтения, направлены на ознакомление с тематикой, отраслевой

отнесенностью и основными информационными узлами текста и предполагают умение на основе

извлеченной информации кратко охарактеризовать текст с точки зрения поставленной проблемы.

Полученные умения и навыки должны быть реализованы в процессе самостоятельного экстенсивного

чтения профильных текстов, которые студент может найти во второй части каждого урока, где

предлагаются более расширенные тексты, ознакомительное чтение которых характеризуется умением

проследить развитие темы и общую линию аргументации автора, понять, в целом, 4/5 специальной

информации, чтобы составить реферат, резюме или презентацию содержания.

Предусмотрено логически и методически обоснованное введение специального материала,

результатом которого должно стать свободное, зрелое чтение и последующее использование информации в

профессиональной практике. Это обеспечивается последовательным формированием умений вычленять

опорные смысловые блоки текста, определять структурно-семантическое ядро, выделять основные мысли и

факты, находить логические связи, исключать избыточную информацию, группировать и объединять

выделенные положения по принципу общности, а также формированием навыка языковой интуиции и

прогнозирования поступающей информации.

Учебник содержит оригинальные тексты, отобранные из числа публикуемых в свободном доступе

Интернета англоязычных научных изданий, которые не налагают ограничения авторского права. Тексты

модифицированы и сокращены, но без какого-либо упрощения АЯ. Именно поэтому во второй части

каждого урока предлагается самостоятельно работать с текстами в области межкультурной,

транснациональной и междисциплинарной коммуникации, представляя индивидуальные отчеты

преподавателю.

Обучение различным видам языковой компетенции на основе интенсивного и экстенсивного чтения

осуществляется в их совокупности и взаимосвязи, с учетом содержательной специфики текста.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

UNIT 1. CULTURAL AWARENESS IN INTERNATIONAL ENGLISH

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 1-1. CULTURAL AWARENESS IN TEACHING AND LEARNING INTERNATIONAL

ENGLISH

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

Text 1-2. CONCENTRIC CIRCLES MODEL OF WORLD ENGLISHES IN WORLD

CONTEXT

UNIT 2. LANGUAGE AS A PART OF A COMPLEX TOTALITY OF CULTURE

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 2-1. INTER-CULTURAL COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

RELATIONS BETWEEN LANGUAGE AND CULTURE

Text 2-2. LANGUAGE AS A PART OF A COMPLEX TOTALITY OF CULTURE

UNIT 3 APPROACHES TO INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 3-1. APPROACHES TO INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

A NEW APPROACH TO A THEORY OF CULTURE

Text 3-2. A THEORY OF CULTURE AND INTERCULTURAL UNDERSTANDING

UNIT 4. CROSS-CULTURAL COMMUNICATION – THE NEW NORM

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 4-1. CROSS-CULTURAL COMMUNICATION – THE NEW NORM

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

THE ISSUE OF CULTURAL DIVERSITY

Text 4-2. INVESTING IN CULTURAL DIVERSITY AND INTERCULTURAL

DIALOGUE

UNIT 5. CROSS-CULTURAL ENGLISH AS THE MEDIUM OF EDUCATION

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

TEXT 5-1. INTERNATIONALIZATION OF UNIVERSITIES

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

PRINCIPLES OF TEACHING TRANSNATIONAL ENGLISH

Text 5-2. TRANSNATIONAL ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING: OPPORTUNITIES

FOR TEACHER LEARNING AND DEVELOPMENT

UNIT 6. HOW TO TEACH MULTICULTURAL COMMUNICATION

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 6-1. HOW TO TEACH MULTICULTURAL COMMUNICATION

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

MULTICULTURALISM FOR EDUCATION IN THE 21ST CENTURY BEYOND CULTURAL

IDENTITY

Text 6-2. WHAT MAKES A SCHOOL MULTICULTURAL?

UNIT 7. LANGUAGE AND DIVERSITY

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 7-1. LANGUAGE AND SUPERDIVERSITY

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

SUPER-DIVERSITY — THE NEW CONDITION OF TRANSNATIONALISM

Text 7-2. SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF SUPER-DIVERSITY

UNIT 8. BASICS OF SOCIOLINGUISTICS

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 8-1. SOCIOLINGUISTICS VERSUS CORE LINGUISTICS

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING SOCIOLINGUISTICS – THE

STUDY OF THE EFFECTS OF LANGUAGE USE ON SOCIETY

Text 8-2. VARIATIONIST CONTROVERSIES IN SOCIOLINGUISTICS

UNIT 9. HOW TO BE AN ETHICAL NEWSPAPER JOURNALIST

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 9-1. ETHICAL CODE OF JOURNALISM IN THE NEW YORK TIMES.

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

OBLIGATIONS OF THE TIMES STAFF MEMBER

Text 9-2. ETHICAL CODE OF JOURNALISM IN THE NEW YORK TIMES.

UNIT 10. CONTENT AND LANGUAGE INTEGRATED LEARNING

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 1-11. CONTENT AND LANGUAGE INTEGRATED LEARNING

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

A NATURAL WAY TO LEARN A LANGUAGE WHEN A SUBJECT IS TAUGHT IN THAT

LANGUAGE

Text 10-2. CLIL TEACHERS’ TARGET LANGUAGE COMPETENCE

UNIT 11. THE USE OF ENGLISH IN INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 11-1. USING ENGLISH FOR INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS: A EUROPEAN CASE

STUDY

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

THE USE OF DOE FOR THE WORKPLACE

Text. 11-2. ENGLISH FOR THE WORKPLACE: SHARING THOUGHTS WITH

TEACHERS AND TRAINERS OF BUSINESS ENGLISH AND ESP

UNIT 12. A NEGATIVE GLOBAL IMPACT OF THE PANDEMIC

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 12-1. A Crisis Like No Other, An Uncertain Recovery

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

UNCERTAINTY IN GLOBAL ECONOMY, POLICY AND HEALTHCARE CHALLENGES

Text 12-2. Evolution of the pandemic is a key factor shaping the economic outlook

UNIT 13. BIODIVERSITY AS THE FOUNDATION OF ECOSYSTEM SERVICES

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 13-1. THE LINK BETWEEN BIODIVERSITY AND ECOSYSTEM SERVICES

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

THE CURRENT TRENDS IN BIODIVERSITY

Text 13-2. A CONTINUING LOSS OF BIODIVERSITY

UNIT 14. BIODIVERSITY IS THE SUM OF ALL LIFE ON EARTH

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 14-1. WHAT IS BIODIVERSITY AND WHERE IS IT FOUND?

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

THE INTERDEPENDENCE OF BIODIVERSITY AND URBANIZATION

Text 14-2 EFFECTS OF URBANIZATION ON BIODIVERSITY

UNIT 15. AN INTERDISCIPLINARY APPROACH TO 21ST CENTURY BIOLOGY

Text 15-1. 21ST CENTURY BIOLOGY: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY APPROACH

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

A MULTI/INTERDISCIPLINARY APPROACH FOR THE 21ST CENTURY

Text 15-2. A NEW BIOLOGY FOR THE 21ST CENTURY

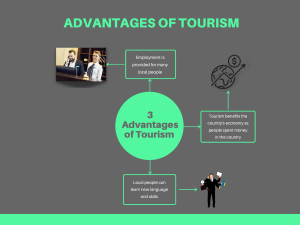

UNIT 16. INTERNATIONAL TOURISM: A GLOBAL FORCE FOR ECONOMIC GROWTH AND

DEVELOPMENT

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 16-1. THE MULTI-DIMENSIONAL IMPACT OF INTERNATIONAL

TOURISM

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

INTERCONNECTION OF MIGRATION AND TOURISM

Text 16-2. MIGRATION AND TOURISM FOR ECONOMIC GROWTH

UNIT 17. THE COMPETITIVENESS OF TOURISM AND HOSPITALITY BUSINESS

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 17-1. DESTINATION COMPETITIVENESS IN TOURISM

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING COMPETITIVENESS IN

HOSPITALITY INDUSTRY

Text 17-2. COMPETITIVENESS OF THE HOTEL INDUSTRY IN THE

REGIONAL MARKET

UNIT 18. MANAGING HOSPITALITY BUSINESS

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 18-1. HOTEL MANAGEMENT AGREEMENTS Part 1.

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING FEES FOR MANAGING

HOSPITALITY BUSINESS

Text 18-2. HOTEL MANAGEMENT AGREEMENTS. Part 2.

UNIT 19. LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE AS A SCIENCE

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 19-1. INTERDISCIPLINARY CHARACTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

AS A SCIENCE

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE FOR URBAN AND RURAL AREAS

Text 19-2. LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN DESIGN AS A PROFESSION

AND SCIENCE

UNIT 20. PUBLIC SPEAKING FOR BUILDING PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 20-1. WHAT IS PUBLIC SPEAKING? AND WHY IS IT IMPORTANT?

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

PUBLIC SPEAKING AS COMMUNICATION PRACTICE

Text 20-2. PUBLIC SPEAKING IN CULTURAL CONTEXTS

GRAMMAR SUPPLEMENT

INTRODUCTION

This Manual is a guide to the graduate instruction in interdisciplinary Domain-Oriented English (DOE).

Step-by-step procedures are outlined for assessing students’ needs, setting achievable goals, and selecting

appropriate materials and activities for the learners. Out of the four language skills the Manual describes three –

reading, writing, and speaking, and provides suggestions for employing these skills in the transnational and

intercultural communication.

Being a graduate university student the learner has had a four-year long previous experience learning

English as a second language (ESL) or English as a foreign language (EFL), and your first question on receiving

your current assignment to learn DOE may be: "How is ESP different from ESL?"

How is DOE different from English as a Second Language, or general English?

The major difference between DOE and ESL lies in the learners and their purposes for learning English.

DOE students are adults who already have familiarity with English and are learning the language in order to

communicate using a set of professional skills and to perform particular job-related functions. A DOE program is

therefore built on an assessment of purposes and needs and the functions for which English is required.

As a matter of fact, DOE is part of a shift from traditional concentration on teaching grammar and language

structures to an emphasis on language in a multidisciplinary context. DOE covers subjects ranging from World

Englishes or sociolinguistics to tourism and business management.

For students specializing in multidisciplinary skills the field of professional activity covers all kinds of

transnational communication ranging from intercultural ESL to hospitality in international tourism and business

servicing. The DOE focus means that English is not taught as a subject divorced from the students' future jobs;

instead, it is integrated into a subject matter area important to the learners.

Consequently, ESL and DOE diverge not only in the nature of the learner, but also in the goals of instruction. In

fact, as a general rule, while in ESL all four language skills; listening, reading, speaking, and writing, are stressed

equally, in DOE it is a needs analysis that determines which language skills are most needed by the students, and the

syllabus is designed accordingly.

EFL/ESL and DOE differ is in the emphasis on the skills to be activated. Whereas in EFL/ESL all four

language skills; listening, reading, speaking, and writing, are stressed equally, in DOE a needs assessment

determines which language skills are most needed by the students, and the program is focused accordingly.

A DOE program might, for example, emphasize the development of reading skills in students who are

preparing for graduate work as business analysts and translators in international business; or it might promote the

development of spoken skills in students who are studying English in order to become tourist guides.

The students' interest in their prospective subject-matter fields, in turn, enhances their ability to acquire English. The

DOE class takes the meaningful context and shows students how the same information is expressed in English. The

teacher can exploit the students' knowledge of the subject matter in helping them master English deeper and faster.

The graduate students approach the final period of their study of English through a field that is already

known and relevant to them. This means that they are able to use what they learn in the DOE classroom right away

in their work and studies. The DOE approach enhances the relevance of what the students are learning and enables

them to use the English they know to learn even more English, since their interest in their professional field will

motivate them to interact with speakers and texts. DOE assesses needs and integrates motivation, subject matter and

content for the teaching of relevant skills.

What is the role of the learner and what is the task s/he faces?

The graduate students attend the DOE class with a specific interest for learning, subject matter knowledge, and wellbuilt learning strategies, because it is powerful tool for creating opportunities in their professional activities or

further studies.

The more learners pay attention to the meaning of the language they read and analyze, the more they are successful;

and on the contrary, the more they have to focus on the linguistic input or isolated language structures, the less they

are motivated to attend their classes.

The DOE graduate students are particularly well disposed to focus on meaning in authentic contexts and on the

particular ways in which the language is used in functions that they will need to perform in their fields of research or

jobs.

Graduate students are generally aware of the purposes for which they will need to use English. Having already

oriented their education toward a specific field, they see their English training as complementing this orientation.

They have to work harder than they have used to before, but the learning skills they have already developed in using

their English make the language learning abilities in the DOE classroom potentially immense. They will be

expanding vocabulary, becoming more fluent in their fields, and adjusting their linguistic behavior to new situations

or new roles.

To summarize, students bring to DOE the focus for learning, subject matter knowledge, new learning strategies.

They can exploit these innate competencies in learning English because DOE combines purpose, persistence,

motivation, context-relevant skills.

The teacher’s role in the DOE classroom is to organize programs, set goals and objectives, establish a positive

learning environment, evaluate students' progress.

Assessing students’ needs and skills

What language skills will the students need to develop in order to perform these tasks? Will the receptive

skills of reading and listening be most important, or the productive skills of writing and speaking – or some other

combination?

The Common European Framework (CEF) describes what a learner can do at six specific levels: Basic

User (A1 and A2); Independent User (B1 and B2); Proficient User (C1 and C2).

These levels match general concepts of basic, intermediate, and advanced and are often referred to as the

Global Scale.

The Global Scale is not language-specific. In other words, it can be used with virtually any language and

can be used to compare achievement and learning across languages. For example, an A2 in Spanish is the same as an

A2 in Japanese or English.

The Global Scale also helps teachers, academic coordinators, and course book writers to decide on

curriculum and syllabus content and to choose appropriate course books, etc.

The Global Scale is based on a set of statements that describe what a learner can do. The “can do”

statements are always positive: they describe what a learner is able to do, not what a learner cannot do or does

wrong. This helps all learners, even those at the lowest levels, see that learning has value and that they can attain

language goals.

Common Reference Levels - The Global Scale

Basic A1

• Can understand and use familiar everyday expressions and very basic phrases aimed at the satisfaction of needs of

a concrete type.

• Can introduce him/herself and others and can ask and answer questions about personal details such as where

he/she lives, people he/she knows and things s/he has.

• Can interact in a simple way provided the other person talks slowly and clearly and is prepared to help.

Basic A2

• Can understand sentences and frequently used expressions related to areas of most immediate relevance (e.g. very

basic personal and family information, shopping, local geography, employment).

• Can communicate in simple and routine tasks requiring a simple and direct exchange of information on familiar

and routine matters.

• Can describe in simple terms aspects of his/her background, immediate environment and matters in areas of

immediate need.

Independent B1

• Can understand the main points of clear standard input on familiar matters regularly encountered in work, school,

leisure, etc.

• Can deal with most situations likely to arise while travelling in an area where the language is spoken.

• Can produce simple connected text on topics which are familiar or of personal interest.

• Can describe experiences and events, dreams, hopes and ambitions and briefly give reasons and explanations for

opinions and plans.

Independent B2

• Can understand the main ideas of complex text on both concrete and abstract topics, including technical

discussions in his/her field of specialization.

• Can interact with a degree of fl uency and spontaneity that makes regular interaction with native speakers quite

possible without strain for either party.

• Can produce clear, detailed text on a wide range of subjects and explain a viewpoint on a topical issue giving the

advantages and disadvantages of various options.

Proficient C1

• Can understand a wide range of demanding, longer texts, and recognize implicit meaning.

• Can express him/herself fluently and spontaneously without much obvious searching for expressions.

• Can use language flexibly and effectively for social, academic and professional purposes.

• Can produce clear, well-structured, detailed text on complex subjects, showing controlled use of organizational

patterns, connectors and cohesive devices.

Proficient C2

• Can understand with ease virtually everything heard or read.

• Can summarize information from different spoken and written sources, reconstructing arguments and accounts in a

coherent presentation.

• Can express him/herself spontaneously, very fluently and precisely, differentiating finer shades of meaning even in

more complex situations.

A detailed description of Level C1 and Level C2 is given below because these are the ones graduate students

are expected to have closely approached. Consequently, the ESP classroom students are recommended to start by

finding where they are and identify personal objectives to be achieved with the help of this Manual.

Listening

Reading

Speaking

Spoken

Interaction

Speaking

Spoken

Production

Writing

C1

I can understand extended speech even when it

is not clearly structured and when relationships

are only implied and not signaled explicitly. I

can understand television programs and films

without too much effort.

I can understand long and complex factual and

literary texts, appreciating distinctions of style.

I can understand specialized articles and longer

technical instructions, even when they do not

relate to my field.

I can express myself fluently and

spontaneously without much obvious searching

for expressions. I can use language flexibly and

effectively for social and professional

purposes. I can formulate ideas and opinions

with precision and relate my contribution

skillfully to those of other speakers.

I can present clear, detailed descriptions of

complex subjects integrating subthemes,

developing particular points and rounding off

with an appropriate conclusion.

I can express myself in clear, well-structured

text, expressing points of view at some length.

I can write about complex subjects in a letter,

an essay or a report, underlining what I

consider to be the salient issues. I can select a

style appropriate to the reader in mind.

C2

I have no difficulty in understanding any kind of

spoken language, whether live or broadcast, even

when delivered at fast native speed, provided. I

have some time to get familiar with the accent.

I can read with ease virtually all forms of the

written language, including abstract, structurally

or linguistically complex texts such as manuals,

specialized articles and literary works.

I can take part effortlessly in any conversation or

discussion and have a good familiarity with

idiomatic expressions and colloquialisms. I can

express myself fluently and convey finer shades

of meaning precisely. If I do have a problem I can

backtrack and restructure around the difficulty so

smoothly that other people are hardly aware of it.

I can present a clear, smoothly flowing

description or argument in a style appropriate to

the context and with an effective logical structure

which helps the recipient to notice and remember

significant points.

I can write clear, smoothly flowing text in an

appropriate style. I can write complex letters,

reports or articles which present a case with an

effective logical structure which helps the

recipient to notice and remember significant

points. I can write summaries and reviews of

professional or literary works.

Students should receive practice in reading for different purposes, such as finding main ideas, finding

specific information, or discovering the author's point of view. Students should have a clear idea of the purpose of

their reading before they begin. Background information is very helpful in understanding texts. Students need

advance guidelines for approaching each assignment. Knowing the purpose of the assignment will help students get

the most from their reading effort. From the title, for instance, they can be asked to predict what the text is about. It

is also helpful to give students some questions to think about as they read. The way they approach the reading task

will depend on the purpose for which they are reading.

Students are often asked by their Russian teachers to write a referat. The term referat is mostly used in

Russian educational context to nominate a research, which has been done by students and is presented in class or

handed in to the teacher, either on paper or online.

Referat is a German word referring to a student's assignment to prepare a report and give a presentation. It is

often used in English among Russian exchange students studying at a foreign university for lack of a better word.

E.g.: How did your referat go?

I didn't get to give my referat, because we didn't have time for me to give it.

The professor just totally forgot about my referat, so I'll have to do it next week. And I stayed up all

night working on my referat!

Depending on the exact nature of the assignment the corresponding terms in English may be: an abstract, an

essay, a précis, a presentation, a project, a report, a summary.

Abstract is a brief summary of a research paper, which gives an overview of the paper, focusing on its main

points and defining for the reader the outlines of the subject under study. Abstract must be an independent

meaningful text, easy to read (explicit, unambiguous formulation, short sentences) and understandable to the wide

audience. Abstract communicates the objective of research, the research problem, methods of research, results and

their originality, and areas of application. Important facts, relationships and numerical data are also provided.

Abstract ends, in a separate line, with keywords (5-10 words) which identify the subject areas discussed in the

research.

Essay is a free form development of thought on an independently selected or given topic. Important

components are creative thinking and author’s personal reflections; it is not compulsory to prove statements. The

required length of an essay is recommended by the instructor, the most common length being 5−7 pages. The essay

format depends on the problem task and requirements made by the instructor.

Précis (pronounced "preh-see"): is a type of summary or abridgment where you summarize a piece of text, its

main ideas and arguments, in particular, to provide insight into its author’s content. While writing a précis you have

to exactly and succinctly account for the key aspects of the text. If you write a successful précis, it is a good

indication that you've read that text closely and that you understand its major points. It is an excellent way to show

that you've closely read a text. A précis should consist of four brief but direct sentences (components). The first

identifies who wrote the text, where and when it was published, and what its topic and field are. The second

explores how the text is developed and organized. The third explains why the author wrote this, her/his purpose or

intended effect. The fourth and final sentence/passage describes who the intended or assumed audience of this text

is.

Presentation is a means of communication that can be adapted to various speaking situations, such as talking

to a group, addressing an examination board or a class meeting. It can also be used as a broad term that encompasses

other ‘speaking engagements’ such as making a speech or getting a point across in conference. A presentation

requires you to get a message across to the listeners and will often contain a 'persuasive' element. It may, for

example, be a talk about your reading for a graduate or candidate exam. You should know exactly what you want to

say and the order in which you want to say it.

Summary is a quick or short review of a bigger text, presenting the substance of a body of material in a

condensed form; concise. A summarizing abstract or a condensed presentation mentions main points or a general

idea of the text under study in a brief form. To write a good summary it is important to thoroughly understand the

material you are working with. Here are some preliminary steps in writing a summary: 1. Skim the text, noting in

your mind the subheadings. If there are no subheadings, try to divide the text into sections. Try to determine what

type of text you are dealing with. This can help you identify important information. 2. Read the text, highlighting

important information and taking notes. 3. In your own words, write down the main points of each section. 4. Write

down the key support points for the main topic, but do not include minor detail. 5. Go through the process again,

making changes as appropriate.

UNIT 1. CULTURAL AWARENESS IN INTERNATIONAL ENGLISH

Guidelines for intensive reading of DOE texts

Reading is the primary channel through which students will progress in English at the

final stage of the DOE course. The reading program provides instruction in the skills required at

various levels of intensive reading, along with plenty of intensive and continual practice. Timelimited intensive reading depends primarily on the knowledge of vocabulary and subject matter,

and secondarily on the knowledge of grammatical structure and familiarity with the ways by

which authors organize texts in English. Vocabulary development in interdisciplinary links is a

vital aspect necessary for graduate students who have already mastered quite a lot of domainoriented English in their respective fields. However, they will have to expand it for further study.

Vocabulary should be learned only in context, never in word lists to be memorized with

dictionary definitions.

Two types of skills are needed in time-limited intensive reading: simple identification

skills (decoding of the contents), and complex cognitive skills such as analyzing,

synthesizing, and predicting. The reading program should work on two levels to develop both

types of skills.

In order to do this, two types of reading tasks are incorporated in the Manual: intensive

and extensive.

Part 1 of every unit is designed for intensive reading (analyzing, synthesizing, and

predicting) in the classroom through close analysis of shorter passages, and can be used to

develop vocabulary, grammar skills, and comprehension.

Part 2 of every unit is designed for extensive reading (identification or decoding

skills necessary for building independently a condensed presentation of the text) by way of

faster individual reading of longer passages to develop understanding of the authors'

organizational strategies, to improve reading speed, and to focus on the gist of the text.

Grammar Supplement is targeted at grammar problems the students may encounter

while developing their comprehension and cognitive skills necessary for defining the subject

matter of the texts and the way the information is organized.

PART 1. THE SKILLS OF INTENSIVE READING

Text 1-1. CULTURAL AWARENESS IN TEACHING AND LEARNING INTERNATIONAL

ENGLISH (Abridged after G. D. G. Bravo’s Cultural awareness for intercultural communication in

teaching English as an international language. Lo nuevo en Monografias.com, 2018)

1.

With today’s increasing globalization of social and economic activities, people’s

understanding of English learning has been further enhanced. Today, people’s understanding of

the language is no longer limited to the narrow concept “communication tool”. Language is an

inseparable part of culture; it is the carrier of culture. Language reflects the characteristics of a

nation; it contains not only the nation’s historical and cultural background, but also the nation’s

views on life, lifestyle and mode of thinking. To learn a foreign language, you have to master the

knowledge, skills and also have to understand the language which reflected the foreign culture,

so as to overcome cultural barriers, communicate with foreigners decently and effectively and

have both emotional and cross-cultural communication. The changing status of English in the

world as a world lingua franca has resulted in the shift of its position from a foreign or second

language to a medium for international communication. English language learning has become

very popular from primary schools to colleges and universities in Russia. No doubt, the objective

of English language teaching and learning as an international language has much in common

with intercultural communication. Thus, it should be oriented towards the promotion of

intercultural competence as an important and inseparable part of the whole process, because the

primary function of any language is instrumental for interaction and communication. English

language learners are required to be ready to converse fluently in all kinds of academic,

professional and everyday contexts. Therefore, understanding of the relationship between

linguistic competence and intercultural communication competence is important for improving

students’ intercultural communication skills.

2.

Nowadays, professionals have more possibilities of interchanging knowledge, research

projects. They work together due to the increase of International collaboration and it has become

necessary to develop a communicative competence among professionals since there are mobility

options to foster international collaboration. As professionals need to be more competent due to

globalization increasing demands, not only a higher level of knowledge of a language, but also

intercultural competence is necessary. Professionals need to know the language of business and

research but also need to be aware of the cultural background of the interacting foreign partners.

Globalization brings about these new challenges.

The intercultural element is a cornerstone for these kinds of interactions with foreign

cultures and that is why it is quite important to take into account the differences and similarities

of the target culture to be more efficient when it comes to doing business and/or research with

them. Professionals of different branches of science and tourists in general from different

countries are continually traveling abroad to share their science and culture with local people.

These interactions are mostly in English, but the foreign visitors are mostly non-native English

speakers because they can also use English as a foreign language just like us (English-speaking

Germans, Japanese, Russians, etc.). Since English as an International Language has become the

lingua franca of the world today and most of the users of this language are non-native speakers

from neither the United Kingdom nor the United States nor any other English-speaking country.

Communicative language teaching in Asia, Africa, Europe has been doing a successful work to

improve the four essential skills such as writing, speaking, listening and reading at all

educational levels. Although culture is a significant part for the teaching of English, it is always

important to remember that an 'intercultural dimension' in language teaching is a key

component to develop learners as intercultural speakers or mediators who are able to engage

with complex and multiple identities. To avoid the stereotyping which accompanies perceiving

someone through a single identity, teachers should teach international English along with

intercultural awareness as part of the process.

Therefore, an interesting question arises: What could be the importance of cultural

awareness for intercultural communication in teaching English as an international language?

Actually, the implicit task of the teacher is to value the importance of cultural awareness

for intercultural communication in teaching English as an international language. The

evolution and current status of the English language since its origin accounts for the importance

of learning English as an international language. To enhance global communication will be a

point to analyze the importance of cultural awareness in teaching international English

3.

The history of the English language started with the arrival of three Germanic tribes who

invaded Britain during the 5th century AD. The Angles, the Saxons and the Jutes, crossed the

North Sea from what today is Denmark and northern Germany to bring their languages to

Britain. These languages in Britain developed into Old English, then into Middle English, into

Modern English and so on.

From around 1600, the English colonization of North America resulted in the creation of

a distinct American variety of English. Some expressions that the British call "Americanisms"

are in fact original British expressions that were preserved in the colonies while lost for a time in

Britain. Spanish also had an influence on American English (and subsequently British English).

French words (through Louisiana) and West African words (through the slave trade) also

influenced American English (and so, to an extent, British English). English has experienced a

rich development over the years up to the point that it is not only used as a native language but

also as an official or foreign language all over the world.

Of the 4,000 to 5,000 living languages, English is by far the most widely used. As a

mother tongue, it ranks second only to Chinese, which is effectively six mutually unintelligible

dialects little used outside China. On the other hand, the 300 million native speakers of English

are to be found in every continent, and an equally widely distributed body of second language

speakers, who use English for their day-to-day needs, totals over 500 million. Finally, if we add

those areas where decisions affecting life and welfare are made and announced in English, we

cover one-sixth of the world's population. Barriers of race, color and creed are no hindrance to

the continuing spread of the use of English. Besides being a major vehicle of debate at the

United Nations, and the language of communication for the European Union, it is the official

language of international aviation, and unofficially is the first language of international sports

and the pop scene.

More than 60 per cent of the world's radio programs are broadcast in English and it is

also the language of 70 per cent of the world's mail. From its position 400 years ago as a

dialect, little known beyond the southern counties of England, English has grown to its present

status as the major world language. Today, it is true that American English is particularly

influential, due to the USA's dominance of cinema, television, popular music, trade and

technology (including the Internet). But there are also many other varieties of English around the

world, including for example Australian English, New Zealand English, Canadian English, South

African English, Indian English and Caribbean English.

English is not the prerogative or possession" of the English nation. Acknowledging this

must – as a corollary – involve our questioning the propriety of claiming that the English of one

area is more "correct" than the English of another. Certainly, we must realize that there is no

single "correct" English, and no single standard of correctness.

Then, the expression "world Englishes" is capable of a range of meanings and

interpretations. In the first sense, perhaps, the term functions as an umbrella label referring to a

wide range of differing approaches to the description and analysis of English(es) worldwide.

Some scholars, for example, favor a discussion of "world English" in the singular, and also

employ terms such as "global English" and "international English," while others adopt the same

terms in their plural forms. Indeed, in recent years, a plethora of terminology has come into use,

including: English as an international (auxiliary) language, global English(es), international

English(es), localized varieties of English, new varieties of English, non-native varieties of

English, second-language varieties of English, world English(es), new Englishes, alongside such

more traditional terms as ESL (English as a Second Language) and EFL (English as a Foreign

Language).

4.

English as an International Language has become the lingua franca of the world today.

An essential factor of this widespread use of English is the fact that, as it was said before, most

of the users of the English language today are not native speakers from either the United

Kingdom or the United States or any naïve English-speaking country.

For better or worse, English has "traveled" to many parts of the world and has been used

to serve various purposes. This phenomenon has created positive interactions as well as tensions

between global and local forces and has had serious linguistic, ideological, sociocultural,

political and pedagogical implications. As English rapidly develops more complex relationships

within and between communities of speakers around the world, the dialogue addressing its role

as a global language needs to continue to expand.

English is the product of a world econocultural system and is the preferred medium of the

international communities of business, science, culture and intellectual life. Therefore, the

demand for English has rapidly escalated among adult learners including immigrants to Englishspeaking countries, business people involved in the global economy, and those who just want to

travel as tourists. In many countries, large-scale English Language Teaching programs for adult

learners have been established in the community and workplace as a result of the globalization of

the workforce, the perceived need to increase economic competitiveness, and a move towards

life-long learning. We should teach English as an international language (EIL). The cultural

content for teaching materials in EIL can be target culture materials (e.g., American, British,

Australian, etc. scenes), local culture materials, or international culture materials (e.g.,

international tourism and social contact).

5.

English as an international language has also started to develop a close affinity with

research in the area of intercultural communication. English is widely used for intercultural

communication at the global level today. It is becoming increasingly recognized that

"intercultural competence" needs to be viewed as a core element of "proficiency" in English

when it is used for international communication. It is true that despite the need for some culture,

users of English as an international language do not need to internalize the cultural norms of the

original native-English speaking countries in order to effectively utilize the language. Since

English as an international language does not necessarily "belong" to any country what teachers

do need to recognize is the need to broaden their students' horizon beyond the purely linguistic

aspects. It can be done not only by placing greater weight on the cultural background of the

target language (TL) countries, but also by trying to raise some kind of intercultural awareness

and bringing about Intercultural Communicative Competence. This comprehensive competence

integrates the cognitive (knowledge of languages and cultures), the pragmatic (the competence to

perform speech acts) and the attitudinal domains (open-mindedness and tolerance, as in political

education) within EFL learning. Therefore, teachers need to develop some sort of intercultural

dimension in the classroom.

6.

When two people talk to each other, they do not just speak to the other to exchange

information, they also see the other as an individual and as someone who belongs to a specific

social group, for example a 'worker' and an 'employer' or a 'teacher' and a 'pupil'. This has an

influence on what they say, how they say it, what response they expect and how they interpret

the response. In other words, when people are talking to each other their social identities are

unavoidably part of the social interaction between them. In language teaching, the concept

of communicative competence takes this into account by emphasizing that language learners’

need to acquire not just grammatical competence but also the knowledge of what is 'appropriate'

language.

Now, 'intercultural dimension' in language teaching aims to develop learners

as intercultural speakers or mediators who are able to engage with complexity and multiple

identities and to avoid the stereotyping which accompanies perceiving someone through a single

identity. It is based on perceiving the interlocutor as an individual whose qualities are to be

discovered, rather than as a representative of an externally ascribed identity. Intercultural

communication is communication on the basis of respect for individuals and equality of human

rights as the democratic basis for social interaction.

7.

Intercultural awareness in language learning is often talked about as though it were a

'fifth skill' - the ability to be aware of cultural relativity following reading, writing, listening and

speaking. Language itself is defined by a culture. We cannot be competent in the language if we

do not also understand the culture that has shaped and informed it. We cannot learn a second

language if we do not have an awareness of that culture, and how that culture relates to our own

first language/first culture. It is not only therefore essential to have cultural awareness, but also

intercultural awareness. Then, it is necessary to review these key elements and their relevance to

accomplish the purposes of this paper:

Intercultural communication: common, necessary part of people’s personal and

professional lives.

Intercultural competence: ability to become effective and appropriate in

interacting, the sensitivity to cultural diversity.

Cultural awareness: an important role to overcome difficulties to ensure smooth

communication with people from different backgrounds.

Intercultural communication competence: ability to effectively and

appropriately execute communication behaviors to elicit a desired response in a specific

environment.

OVERVIEW QUESTIONS: THE FIELD OF RESEARCH, THE SUBJECT

MATTER, THE MAIN TOPIC, AND THE MAIN PURPOSE OF THE TEXT

Instruction: After almost every text, the first question you should ask is an overview

question about the field of research, the subject matter, the main topic and/or the main purpose

of the text. Overview questions lead you to identify the most important concepts and ideas in the

text.

You can employ two ways of answering the field of research and subject matter

questions: matching headings with paragraphs or sections, and identifying which sections

relate to certain topics. You should use the skill of surveying the text for both types of

questions, but because the strategies are slightly different for each question type, we will look

at them separately.

1. Matching headings with paragraphs

Step 1. Survey the whole text.

Step 2. Survey each paragraph to identify the topic. The words of the topic

sentence might be found in a paragraph. Survey the paragraph to make sure.

Step 3. Choose the correct wording of the research field from the text.

Match the given 7 headings with the 7 paragraphs of the text:

Intercultural awareness in

communication competence

Origins,

evolution

and

current status of English

The language is no longer a

plain “communication tool”

The intercultural dimension'

in language teaching

Implications of learning

English

as

an

International

Language

Cultural

awareness

in

teaching international English

International English for

intercultural

communicative

competence

2. Identifying where to find information

Step 1. Survey the text

Step 2. Read the questions and statements to identify the field of research,

the topic, and the purpose, underline the key words in the question, read one question or

statement at a time.

a/ The implication of the text is what the author has in mind when s/he is writing

it. Which one of the sentences given below most closely renders the main idea of the

text?

1. Intercultural interactions have become very frequent in various fields of action. As the

intercultural element is a key factor for these kinds of interactions, it is quite important to take

into account the differences and similarities of the target culture to be more efficient when it

comes interacting with them.

2. Our foreign contacts are not only native English speakers. Therefore, all of them have

different cultural backgrounds.

3. The aim of the paper is to value the importance of cultural awareness for

intercultural communication in teaching English as an international language.

4. We are able to analyze the relevance of cultural awareness for international English

teaching and learning through the analysis of the evolution and current status of the English

language since its origins.

5. The importance of learning English as an international language is in enhancing global

communication and cultural awareness of international English.

b/ The topic is the subject area the author chooses to bring her/his idea to the

reader. Identify the main topic of the text.

1. Complex international, economic, technological and cultural changes that account for

the leading position of English as the international language.

2. The text deals with the origins, evolution and current status of the English language in

the world.

3. The future of languages in the world is discussed.

4. The text defines the importance of learning English as an international language to

enhance global communication.

5. The role of cultural awareness in teaching international English is analyzed.

c/ The purpose of the text is what the author wants the reader to believe in. Does

the writer want you to believe that:

1. The expression "world Englishes" is capable of a range of meanings and

interpretations?

2. The intercultural element is a cornerstone for international communication in English?

3. English is the product of a world econocultural system and the preferred medium of

the international communities of business, science and culture?

4. To learn a foreign language, you not only have to master the knowledge and skills but

also the ways and means helping to overcome cultural barriers?

5. The relative importance of the world’s languages depends on the fields they are used

in?

Note: When there is not a single, readily identified subject matter, main topic questions

may be asked. These ask you what this or that passage is generally "about."

Sample Questions

What is the main topic of the passage?

What does the passage mainly discuss?

What is the passage primarily concerned with?

Main purpose questions ask why the author wrote a passage. The answer choices

for these questions usually begin with infinitives.

Sample Questions

• What is the author's purpose in writing this passage?

• What is the author's main purpose in the passage?

• What is the main point of this passage?

• Why did the author write the passage?

Sample Answer Choices

To define_____

To relate_____

To discuss_____

To propose_____

To illustrate_____

To support the idea that_____

To distinguish between _____and______

To compare ____and_____

Main detail questions ask about the most significant information of the passage.

To answer such question, you should point out a line or two in the text.

Sample Questions

What idea is emphasized in the passage?

In what line is the most significant information given?

Caution:

The process of answering the detail questions may give you a clearer understanding of the

main concept, subject matter, or purpose of the passage.

In fact, the correct answers for these questions summarize the main points of the passage;

they must be more general than any of the supporting ideas or details, but not so general that they

include ideas outside the scope of the passages.

Distractors for this type of question have one of the errors:

They are too specific.

They are too general.

They are incorrect according to the passage.

They are irrelevant (unrelated) to the main idea of the passage.

E.g.: What information is emphasized in the third passage? (A) English is the

language of international communication; (B) Cultural awareness is typical for speakers of

all languages; (C) More than 60 per cent of the world's radio programs are broadcast in

English; (D) Barriers of race, color and creed are no hindrance to the continuing spread of the

use of English.

Distractor (A) is too general. Distractor (B) is incorrect according to the passage.

Distractor (D) is too specific. Answer (D) is correct.

Note: If you're not sure of the answer for one of these questions, go back and quickly

scan the passage. You can usually infer the main concept, the subject matter, the main topic, or

the main purpose of the entire passage from an understanding of the main ideas of the paragraphs

that make up the passage and the relationship between them.

PART 2. THE SKILLS OF EXTENSIVE READING

WORLD ENGLISHES IN WORLD CONTEXTS

Guidelines for extensive reading of DOE texts

Extensive reading of Domain-Oriented English texts is emphasized in this manual as a

way of developing the graduates’ competence in domain-oriented communication embracing

interdisciplinary topics. It implies independent study of the texts discussing vital issues of

professional and general interest. A plausible definition of extensive reading as a competence

acquiring procedure is based on: (1) abridged presentations of longer texts; (2) general

understanding of the research field; (3) the learner’s intention of gaining specific experience and

acquiring special information from the text. (4) Extensive reading is individualized, with

students being offered a choice of interdisciplinary texts they would want to read; (5) the texts

may or may not be discussed in class.

Text 1-2. CONCENTRIC CIRCLES MODEL OF WORLD ENGLISHES IN

WORLD CONTEXTS (Abridged after Braj B. Kachru’s World Englishes in World

Contexts // A companion to the history of the English language / edited by H. Momma and

M. Matto. Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2008).

1. The 3 phases of the English language expansion

The concept “World Englishes,” and the spread of the English language as a global

phenomenon, is better contextualized if the diasporic locations of the language are related to the

colonial expansion of the British empire. The first phase of diaspora was initiated with the Act of

Union that annexed Wales to England in 1535. The result was that speaking English became

essential for success in Wales. In 1603 – just 68 years after Wales – Scottish monarchy lost its

independence. The march of the Empire continued into Ireland – yet another non-English

speaking region. In 1707 the state of Great Britain was established, and the English language

further expanded its territory – it was no longer only the language of England.

The second phase of diaspora implanted the language across the continents: on the one

side in North America including Canada, on the other side in Australia and New Zealand.

It was during the third phase, the glorious period, when the sun never set on the British

Empire, and now never sets on the English language. The English-speaking people came into

direct contact with structurally, and culturally, unrelated languages, e.g., African, East Asian,

and South Asian. These distinctly different contexts of linguistic ecology opened up,

theoretically and methodologically, challenging research areas in language contact and

convergence and multilingual interactions.

2. Issues of the norms and standards of English

In later years, when English became a part of the educational systems in these far flung

colonies, the linguistic, cultural, and ideational challenges raised issues about the norms,

standards, and content of the methodology and models for the teaching and learning of English.

A variety of conceptual frameworks have been suggested for characterization of the

unprecedented cross-cultural global spread of the English language. These issues continue to be

discussed, debated, and constructed in various ideological and theoretical frameworks with

increasing vehemence and aggressiveness. One such framework, Braj Kachru’s Concentric

Circles model, presents a schema for historical, educational, political, social, and literary

contextualization of the English language with reference to its gradual – and unprecedented –

expansion with the ascendancy of the post-colonial period. This representation of the spread of

English is not in terms of any hierarchical priority, or any preferential ranking.

The Inner Circle is inner with reference to the origin and spread of the language. It

includes the majority of English as Language 1 users (e.g., in Britain, USA, Canada, Australia,

and New Zealand). The Outer is outer with reference to geographical expansion of the language

– the historical stages in the initiatives to locate the English language beyond the traditional

English-speaking Britain; the motivations, strategies, and agencies involved in the spread of

English; the methodologies involved in the acquisition of the language; and the depth in terms of

social penetration of the English language to expand its functional range in various domains,

including those of administration, education, political discourses, literary creativity, and media.

The Outer Circle includes the Anglophone colonized countries in, for example, South and East

Asia, and Africa (India, Malaysia, Nigeria, Singapore). The Expanding Circle has a different

historical narrative with reference to acquisition of English than the Outer Circle. The

constituents of this Circle, e.g., China, Europe (inc. Germany, Russia), Iran, Iraq, Korea, Saudi

Arabia, Taiwan, Thailand, provide yet another story of history and acquisition of English. This

representation of the spread of English is not in terms of any hierarchical priority, or any

preferential ranking.

Outer circle (Institutional varieties in India,

Nigeria, Singapore, etc.)

Inner circle (National varieties in the

US, Great Britain, Australia, etc.)

Extending circle (Practical varieties in

Japan, Russia, Malaysia, etc.)

What happened to diasporic Englishes is not different from what has happened to other

such diasporic languages in other parts of the world: Francophone varieties of French, Swahili

varieties in parts of Africa, Spanish in Latin America, and languages such as Arabic in different

Arab states.

In the case of English, the colonized territories of the Empire had their distinct

geographies, their traditional – and longstanding – social, cultural, religious, and administrative

realities. There were also long and rich oral and literary traditions. The English language may not

necessarily have been their “native” language, as language specialists define it. However, as time

passed, in many Outer Circle regions English acquired “functional nativeness” in terms of its

social penetration, and expanded its “range” in terms of local domains of function. The Englishspeaking regions in each Circle are indeed dynamic and not static – or unchanging.

In historical terms, then, the Inner Circle comprises not only its own L1 speakers but also

“functional native” English speakers of the Expanding Circle (e.g. China, Indonesia, Russia,

Thailand), the Outer Circle (e.g. India, Singapore, Philippines).

This Concentric Circles model represents the democratization of attitudes to English

everywhere in the globe.

3. World Englishes

As these regional styles and registers evolved and developed, the linguistic creativity in a

variety of functional contexts gradually manifested itself in, what is termed, acculturation and

nativization (indigenization) of World Englishes. The medium of a transplanted imperial

language was hybridized in the local – African, Asian, European, and Latin American – sociocultural, ideological, and discoursal contexts. The language acquired yet other meaning systems

and ways of representing them. It is through these linguistic processes that the Africanization,

Europization, and Asianization of the English language began.

The same regular linguistic processes had earlier worked in the case of the

Americanization of American English, or Englishes in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. The

conceptual terms, “nativization” and “acculturation,” refer to the changes a language – or its

varieties – undergo at one or more linguistic levels, e.g., phonetic, lexical, syntactic, stylistic, and

discoursal.

The range of speech communities of Englishes includes, for example, monolinguals,

bidialectals, bilinguals, and multilinguals. In many regions of the English-using world, the

traditional dichotomies of native vs. non-native or L1 and L2 users are not necessarily applicable

or insightful. An unparalleled feature of World Englishes is that among the languages of wider

communication, Englishes comprise more users who have acquired a variety of language as an

L2, L3 or L-nth language in their language repertoires. It is evident that the two major Englishusing countries in the world are India and China, both in the Outer and Expanding Circles of

English.

We see that ongoing process are active in East and South Asia, Europe, several parts of

Africa, and other regions. The debate still continues about methodological questions and more

pragmatic issues concerning intelligibility in the varieties of Englishes and cross-cultural

communication among the various users. Who determines the models and standards for varieties

of world Englishes? An answer to this question has been debated, discussed, and vehemently

argued not only with reference to Outer and Expanding Circles: there is a long history of debates

for an appropriate model(s) for Inner Circle countries. What is standard English?

American linguist Leonard Bloomfield provides an insightful answer: Children who are

born into homes of privilege, in the way of wealth, tradition, or education, become native

speakers of what is popularly known as “good” English or standard English. Less fortunate

children become native speakers of “bad” or “vulgar” or nonstandard English.

The speech communities of world Englishes have traditionally been divided thus: those

who are considered privileged – norm-providing – native speakers, primarily from the Inner

Circle; those Anglophone countries who use institutionalized varieties of English in their local

sociolinguistic contexts in, for example, Africa and Asia, are considered non-native speakers –

speakers from the Outer Circle; and those who have assigned restricted roles to English in their

educational and administrative policies and have no extended history of the use of English,

comprise the Expanding Circle (e.g., China, Japan, Korea, the Middle East, Russia, Thailand).

The Expanding Circle has traditionally been dependent on external “educated” models, primarily

from the Inner Circle.

4. The 4 myths of World Englishes

The question of models and standards ultimately is a social, and attitudinal, question. The

reality of World Englishes is that of pluracentricism, multiculturalism, and multicanonicity – that

of hybridity and fusion. The mythology, however, continues to emphasize the following four

myths which may be characterized as follows:

1. The interlocutor myth that most of the interaction in Englishes takes place between L1

speakers and L2 speakers of the language. In the real world of Englishes, the language is a

medium of communication among and between those who use it as an additional language:

Singaporeans with Indians, Japanese with Chinese and Taiwanese, Germans with Pakistanis and

Nigerians. The interlocutors cover a large spectrum of cultures, nationalities, mix of languages,

regions, and identities. The medium of communication – spoken and/or written – is from a wide

varieties of World Englishes.

2. The monoculture myth that English represents primarily – if not essentially – the

Anglo-Saxon traditions and dominant ideologies of the Inner Circle. In the real world of

Englishes, the medium is used to impart local and native religions, cultural and social traditions –

Asian, African, and Latin American. There is abundant evidence of this in nativized, culturespecific acculturation in creative writing, media, popular social culture, and discourses.

3. The mode-dependence myth that the exocentric models (of the Inner Circle), in spoken

or written mediums, have become codes of communication in Anglophone Asian, European, and

African countries. In the real world of African, European, and Asian communicative contexts, it

is the endocentric (local/regional) varieties that have currency. In spite of language policing in

favor of exocentric models of English, the prevalent varieties are those of endocentric Englishes.

This conflict about the choice between localized and external models has resulted in much

discussed linguistic schizophrenia.

4. The myth that the impending linguistic disasters of canonical standards of the English

language are inevitable if variations and linguistic diversification and creativity are not curtailed.

In the real world of Englishes, it is through the processes of acculturation and innovations that,

contextually and culturally, Asian, European, and African identities of World Englishes have

been constructed, thus enriching the Englishes.

It is well demonstrated now that bilinguals’ creativity has resulted in a variety of

linguistic processes and cultural transference that include, for example, stylistic, lexical, and

discoursal innovations. The hybridization, blending, and fusion of languages, and “mixing” of

subvarieties of an institutionalized variety of English, is effectively used in, for example,

Singlish in Singapore English, Bazaar or Babu varieties in South Asian Englishes, and pidgins in

Nigerian English. The medium of English is appropriately adapted and localized to the contexts

of local interactions and discourses. The institutionalized varieties have acquired the “right” by

demonstrating the relationship between discourse structure and thought patterns, and by their

distinct architecture of language.

5. Relevant perspectives of the ownership of World Englishes

There is now increasing realization that the identities and multiple functions of World

Englishes are better conceptualized if the traditional “owners” and “ownership” of English – and

its linguistic and cultural norms of creativity – are viewed from contextually relevant

perspectives. Those perspectives entail a shift in theoretical, methodological, and socio-cultural

constructs of the language and its users. In its varied functions, across cultures and languages,

the current profile of the English language includes the following characteristics:

1. The models for creativity in the language are provided by multi-norms of literary and

oral styles and strategies.

2. The processes of nativization and acculturation in Asian, European, African, and other

varieties are determined by distinctly different linguistic contexts and cultures, and “contexts of

situation.”

3. The interaction in the language is not necessary between two or more monolingual

“speakers-hearers,” but often includes two or more multilingual users of the language.

4. The bilingual’s or multilingual’s creativity and linguistic strategies are not identical to

the interactional strategies of two monolinguals.

5. Bilinguals’ creativity is not merely the interaction and mixing of two or more

languages, but also a fusion of multiple cultural, aesthetic, social, and literary backgrounds. In

other words, the readers and hearers who are not part of the speech-fellowship of the variety of

English, who do not share, or recreate, the “meaning system,” have to familiarize themselves

with linguistic processes and discoursal strategies. What we find inhibiting, limiting,

unintelligible, or non-English in one variety of World Englishes may actually be the result of

linguistically, culturally, and contextually appropriate use of the language. communication. The

sociolinguistically complex sites of English-using African, Asian and European societies are no

more exotic side-shows, but important sites of contact, negotiation, and linguistic creativity.

Instruction: After almost every text, the first question you should ask is an overview

question about the research field, the subject matter, or the main purpose of the text. These

questions ask you to identify most important points in the text, the essence or topic of a passage.

Sample Question

What is the research field of the text? Choose the right answer.

(A) The movement of people as the main reason for language spread and linguistic

consequences.

(B) the Anglo-Saxon traditions and dominant ideologies in the real world of Englishes.

(C) The traditional dichotomies of native vs. non-native or L1 and L2 users,

(D) The theory of language spread as a global phenomenon.

Sample Question

What is the subject matter and main topic of the passage? Choose the right answer.

(A) Lack of English in some countries.

(B) Need for face-to-face international communication and a growing role for global

English.

(C) The reality of of hybridity and fusion of World Englishes.

(D) The impact of globalization on languages.