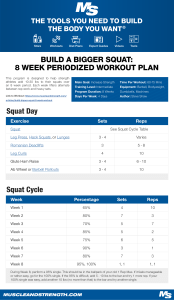

Kingwood Strength & Conditioning: Programming & Training Andy Baker CONTENT PROGRAMS ...................................................................................................................... 8 The KSC Texas Method ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Basic Texas Method Overview ..................................................................................................................... 10 Volume Cycling ............................................................................................................................................. 12 3-Day Texas Method (Bench Press Focus) ................................................................................................... 13 Frequently Asked Questions (Don’t Skip This!) ............................................................................................ 21 The KSC Method for RAW Power Lifting ......................................................................................................... 25 Squat Training .............................................................................................................................................. 26 Deadlift Training ........................................................................................................................................... 27 Bench Press & Overhead Press Training ...................................................................................................... 27 How to Start the Program ............................................................................................................................ 28 4-Day Per Week – Power Lifting Focus ........................................................................................................ 28 4-Day Per Week – Strength Lifting Focus ..................................................................................................... 33 FAQs About the Program ............................................................................................................................. 38 A Note on Volume Days…............................................................................................................................. 40 The KSC Method for Power-Building Training Split ......................................................................................... 41 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 41 10 Key Principles for Successful Power-Building .......................................................................................... 44 The Program ................................................................................................................................................. 51 The KSC Method for Power-Building Diet .................................................................................................... 64 Cardio ........................................................................................................................................................... 65 Deloading ..................................................................................................................................................... 66 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................................... 67 Garage Gym Warrior ....................................................................................................................................... 68 Program Overview ....................................................................................................................................... 68 Organization of Training / Weekly Schedule ................................................................................................ 70 Garage Gym Warrior Program ..................................................................................................................... 70 FAQ ............................................................................................................................................................... 75 Strength & Mass After 40................................................................................................................................ 79 Training Week .............................................................................................................................................. 80 Deloading ..................................................................................................................................................... 81 Diet ............................................................................................................................................................... 82 HEAVY-LIGHT-MEDIUM .................................................................................................. 84 Simplifying the Heavy/Light/Medium System – Part 1: Introduction & Squats ............................................. 84 Simplifying the Heavy Light Medium System – Part 2: Pressing ..................................................................... 88 Simplifying the Heavy-Light-Medium Training System – Part 3: Pulling ......................................................... 90 Structuring 12-week Heavy-Light-Medium Programs..................................................................................... 95 Client Q&A #3: Heavy-Light-Medium Set Up & Gym Time Saving Tip .......................................................... 100 Heavy-Light-Medium - A principle with varying potential methodologies ................................................... 103 Heavy-Light-Medium for Mass - An Old Method For New Gains.................................................................. 106 Two Simple “Hacks” for Heavy-Light-Medium Programming ....................................................................... 108 Heavy-Light-Medium (16 FAQs) .................................................................................................................... 110 Heavy-Light-Medium Programming Tips ...................................................................................................... 114 TEXAS METHOD ............................................................................................................ 115 Texas Method Overview ............................................................................................................................... 115 Understanding the Texas Method Intensity Day .......................................................................................... 116 Managing Intensity Day Correctly ................................................................................................................. 116 POWER-BUILDING ........................................................................................................ 122 Optimal Training for Hypertrophy?? ............................................................................................................. 122 The Body Builders’ Cure ................................................................................................................................ 127 A Simple (and Fun) Method for Mass ........................................................................................................... 130 A Fresh Look at Training Frequency For Power-Building .............................................................................. 132 What Rep Range for Hypertrophy? (hint: all of them) .................................................................................. 136 The Benefits of a Dedicated Back Day (why & how) ..................................................................................... 142 Cycling Bench & Incline on 8/5/2 (Power-Building Programming) ............................................................... 146 Deadlifts on Back or Leg Day? + Power-building Split Advice ....................................................................... 150 4 Day Split for Hypertrophy .......................................................................................................................... 152 Frequency & The Power-Building Split.......................................................................................................... 156 Pumpin’ Ain’t Easy ........................................................................................................................................ 159 CONJUGATE PROGRAM ................................................................................................ 160 A Simple & Complete Guide to Conjugate / Westside Training .................................................................... 160 Programming with the Conjugate Method (my favorite features!) .............................................................. 171 Supplemental Work & Accessories on a Conjugate Program ....................................................................... 176 Choose Weakness Over Strength .................................................................................................................. 181 Use What You Got! (Conjugate Method in the Garage Gym) ...................................................................... 182 Garage Gym Conjugate Training (Lower Body Edition)................................................................................. 183 3 Favorite Lower Body Supplemental Lifts.................................................................................................... 184 Why You Should Train the Floor Press .......................................................................................................... 185 PROGRAMMING ........................................................................................................... 186 Which Program Is Right For You?.................................................................................................................. 186 Short Guide To Intermediate Programming ................................................................................................. 189 A Plan For Annual Periodization (Part 1: January – May) ............................................................................. 194 A Plan for Annual Periodization (Part 2: June – December) ......................................................................... 199 Client John Petrizzo – Case Study, Part 1 ...................................................................................................... 204 Client John Petrizzo – Case Study, (Power Lifting), Part 2 ............................................................................ 208 How to Cycle Training Volume (Example Programming Model) ................................................................... 211 Strategy: Rotating Rep Ranges ...................................................................................................................... 215 Why the 8-5-2 Program Works (In a Nutshell) .............................................................................................. 217 Alternating Rung Method ............................................................................................................................. 219 What is a Rotating Linear Progression? ........................................................................................................ 222 Rotating Linear Progression – Meet Prep Question ................................................................................... 226 Time Saving Techniques for Assistance Work ............................................................................................... 228 Training on Imperfect Schedules - Part 1: Training Twice Per Week ............................................................ 232 Training on Imperfect Schedules – Part 2 ..................................................................................................... 235 2 Days a Week Training ................................................................................................................................. 237 K.I.S.S. Training Program ............................................................................................................................... 239 Deload without Detraining ............................................................................................................................ 240 Performance Flexibility ................................................................................................................................. 243 “One All Out Set” vs Multiple Sets ................................................................................................................ 245 Ever Miss Time in the Gym? (How to adjust training when you come back)................................................ 248 2 Random Pieces of Training Wisdom .......................................................................................................... 252 6 Reasons Why Your Training is STUCK (Part 1 of 2) ..................................................................................... 255 6 Reasons Why Your Training is Stuck (Part 2 of 2) ...................................................................................... 259 Monthly Programming – Two Steps Forward, One Step Back ...................................................................... 263 Programming Assistance Work ..................................................................................................................... 266 Great Advice on Assistance Work ................................................................................................................. 270 Are You Training to Heavy? (Part 1) .............................................................................................................. 272 Are You Training to Heavy? (Part 2) .............................................................................................................. 274 Intermediate and Advanced Training: A Few Ideas ...................................................................................... 276 Pulling for Speed: A 6-week Squat & Deadlift Cycle ..................................................................................... 283 Why & How to “AMRAP” Effectively (4 Methods) ........................................................................................ 286 4 Ways To Get More Consistent ................................................................................................................... 289 Case Study: Exploding Bench & Overhead Press Numbers on an Underweight Male .................................. 294 Training OCD – channel it the RIGHT way ..................................................................................................... 297 500 lb Deadlift PR for Frank! (age 67) ........................................................................................................... 300 How To Do a Rest-Pause Set ......................................................................................................................... 301 50% Sets....Build Size & Save Time ................................................................................................................ 302 Top Set + Back Off Set (Simple Low Volume Approach to Hypertrophy) ...................................................... 304 POWER RACK ............................................................................................................... 307 Power Rack Series - Part 1: Rack Pulls........................................................................................................... 307 Power Rack Series - Part 2: Dead-Stop Rack Bench Press ............................................................................. 310 Power Rack Series - Part 3: Standing Rack Press ........................................................................................... 312 Power Rack Series - Part 4: Rack Squats vs Box Squats ................................................................................ 314 Power Rack Series - Part 5: Dead Stop Rack Squats ...................................................................................... 317 SQUAT.......................................................................................................................... 319 The Squat Q&A: Mechanics, Belts & Assistance (Part 1) .............................................................................. 319 The Squat Q&A: Mechanics, Belts & Assistance (Part 2) .............................................................................. 322 The Squat Q&A: Mechanics, Belts & Assistance (Part 3) .............................................................................. 325 The Case for Front Squats ............................................................................................................................. 329 Pause Squat vs Pin Squat vs Box Squat ......................................................................................................... 332 DEADLIFTS .................................................................................................................... 336 Deadlift Programming & Assistance ............................................................................................................. 336 Simple Deadlift Program That WORKS .......................................................................................................... 339 Deadlift Injuries? 4 Step Safety Check .......................................................................................................... 341 Deadlift Variations – What, When, Where, How .......................................................................................... 344 Goodmornings vs RDL vs SLDL ...................................................................................................................... 351 Programming Stiff Leg Deads & Barbell Rows (a simple strategy) ................................................................ 353 BENCH PRESS ............................................................................................................... 356 Blow Up Your Bench Press (3 Easy Tips) ....................................................................................................... 356 Bringing Up Your Bench Press (Frequency, Intensity, Volume, Exercise Selection) ...................................... 359 Bench Press Technique ................................................................................................................................. 363 PRESS ........................................................................................................................... 364 How to Build a Bigger Overhead Press (7-step Blueprint) ............................................................................ 364 A Simple 6-week Overhead Press Program (Get Unstuck!) .......................................................................... 368 ASSISTANCE EXERCISES ................................................................................................. 370 Improving Your Pull-Ups or Chin-Ups: Do’s and Don’ts ................................................................................ 370 ARMS ........................................................................................................................... 373 Why You Have Small Arms (and how to fix it) .............................................................................................. 373 Got Guns? – 5 Tips for Bigger Arms .............................................................................................................. 378 Strengthening & Growing the Biceps (my favorite simple method) ............................................................. 380 An Easy Tricep Training Schedule.................................................................................................................. 383 NUTRITION & CUTTING ................................................................................................. 387 Building a Simple Diet for Mass .................................................................................................................... 387 Best Strength Program While Cutting Body Fat ............................................................................................ 393 Strength & Fat Loss: A Simple Formula ......................................................................................................... 397 And So The Weight Cut Begins…….(Diet Plan) .............................................................................................. 399 CONDITIONING............................................................................................................. 401 The Necessity of Good Conditioning for Lifers .............................................................................................. 401 SCIENCE AND THEORY .................................................................................................. 404 Muscular Tension Part 1 ............................................................................................................................... 404 How Muscles Work .................................................................................................................................... 405 The Initiator of Muscle Growth .................................................................................................................. 406 Tension/Mechano Sensors ......................................................................................................................... 408 Bioengineers to the Rescue ........................................................................................................................ 410 Recruitment and Rate Coding .................................................................................................................... 412 Two Ways to High Tension ......................................................................................................................... 414 Effective Reps ............................................................................................................................................. 416 Summing Up Muscle Tension: Part 1 ......................................................................................................... 419 Muscular Tension Part 2 ............................................................................................................................... 422 Weight on the Bar as a Proxy for Tension .................................................................................................. 423 The Repetition Range Contradiction .......................................................................................................... 424 Progressive Tension Overload .................................................................................................................... 425 Back in the Real World ............................................................................................................................... 428 A Mid Article Summary .............................................................................................................................. 430 Lever Arms, Torque and Force Production ................................................................................................ 430 Torque in Weight Training Movements ..................................................................................................... 433 The Real Implication of Lever Arms............................................................................................................ 434 The Compound Exercise Mistake ............................................................................................................... 435 Problem 1: The Lever Arm Issue ................................................................................................................ 436 The Muscular Involvement Issue ............................................................................................................... 438 What Muscle is Experiencing Optimal Tension Overload? ........................................................................ 440 The Practical Issue of Progression .............................................................................................................. 442 Back to the Compound Exercise Mistake ................................................................................................... 443 Summing Up Part 2 .................................................................................................................................... 444 Muscular Tension Part 3 ............................................................................................................................... 445 A Clarification on Progressive Overload ..................................................................................................... 446 A Brief Digression on Exercise Selection .................................................................................................... 449 Back to Progressive Tension Overload ....................................................................................................... 450 When Lower Weight Means More Tension ............................................................................................... 450 Squats are Complicated ............................................................................................................................. 452 Ok, No More Squat Discussion ................................................................................................................... 454 Summing Up ............................................................................................................................................... 455 When More Weight Means Less Tension................................................................................................... 456 Summing Up ............................................................................................................................................... 459 Back to Repetition Ranges ......................................................................................................................... 459 Being Strong vs. Getting Stronger: Part 1 .................................................................................................. 464 Being Strong vs. Getting Stronger: Part 2 .................................................................................................. 465 Summing Up Part 3 .................................................................................................................................... 468 Programs The KSC Texas Method A clearly defined and easy to follow template for one of the most popular Intermediate Programs available in Practical Programming for Strength Training. This program takes the guess work out of how to set up your Texas Method plan for optimum results and long term usage. Using the principle of Volume Cycling you can avoid the all too common problem of stalling out and overtraining on this very demanding program. Warning: This program is extremely demanding, but extremely effective for long term gains in absolute strength! Everything included: Sets/Reps, Beginning Training Percentages, Assistance work, and Conditioning. Heavy, Hard, Intermediate Barbell Training at it’s best! Since the original publication of Practical Programming for Strength Training, the most popular and widely used programming model presented has undoubtedly been the Texas Method. Over the years the program has proven itself to be wildly effective for gains in strength and muscle mass. The program makes for an easy natural transition from the basic Novice Linear Progression found within Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training for those trainees who prefer simple, full body, barbell based strength training programs. There isn’t a lot of fluff with the Texas Method. The exercise selection is narrow and the only real variables are volume and intensity. This makes for an ideal program for the new intermediate lifter who is still feeling his or her way around the weight room. But make no mistake, while the Texas Method is simple, it is not easy. In fact, it’s very hard. The simple brutality of the program has worked wonders for many, but has resulted in some catastrophic train wrecks for others (by the way, this can be said of almost any program). If you are not familiar with the program, I would suggest reading or re-reading the relevant sections pertaining to Intermediate Training (and the Texas Method specifically) within Practical Programming for Strength Training. This will provide a more in depth back drop to the principles of the programming than what I will be providing here. Before getting into the basic structure of the program and the specific program I will provide here, let us first review the most common mistakes trainees make with the Texas Method that may lead to a lack of progress or burn out. Mistake #1: Not Prioritizing Critical Recovery Factors You’ve heard this before. We don’t grow and get stronger in the gym. We grow and get stronger out of the gym. With any high stress program, the lifter must be as diligent with his or her “out of gym” activities as they are with their “in gym” activities. If you know that you will not or cannot commit to a very diligent recovery strategy then don’t do the Texas Method. If you don’t sleep enough, eat enough, or eat the right kinds of foods on a regular basis, there are less stressful programs for you to try. That being said, no barbell based strength program will be very effective without proper recovery. Proper recovery basically just means that you can get a solid 6-8 hours of sleep every night during the week, and perhaps a few “catch up” hours on the weekends. It means that you are regularly consuming about 1 gram of animal based protein (meat, egg, milk, whey, etc) on a daily basis, and probably an equivalent amount of carbohydrate each day to spare protein for muscle growth. Fats, both saturated and unsaturated should also be consumed daily to help with adequate hormone balance and further sparing of amino acids as an energy source. You should also be limiting your consumption of alcohol as close to zero as possible. For a 200 lb trainee your diet should probably look something like this: Breakfast (approx. 50g protein / 50g carb) Omelet: 6 Whole Eggs w/ 2-3 oz Ground Beef and diced onions/pepper ½ cup Old fashioned Oatmeal (measured dry) 1 Cup Blueberries Meal 2 (approx. 50g Protein / 50g carbs) 8 oz Chicken Breast 8 oz Potato or Sweet Potato 1 cup Steamed Green Vegetable Meal 3 (approx. 50g Protein / 50g carbs) 2 Scoops Whey Protein 1 packets Instant Oats 1 large banana Meal 4 (approx. 50g Protein / 50g carbs) 8 oz Salmon or Sirloin ¾ cup Rice (measured dry) 1 cup Steamed Green Vegetable This would be a starting point, and it may require more protein / calories than this at some point. Stress is another important variable in the recovery process and if you’ve lived long enough and trained long enough you probably know this. Those of you with very high stress careers or family lives need to find ways to mitigate those stressors or choose to train on a different program. Mistake #2: Trying to “cut” on the Texas Method This goes hand in hand with Mistake #1. You cannot ask your body to go in two different directions at once. Many people end their novice linear progression a little heavier than they’d like and their first priority as an intermediate is to embark on a “cut” to shed excess body fat. Fine by me. But don’t do it while simultaneously trying to run the Texas Method. Training heavy twice per week on each lift will require a slight caloric surplus most likely to fuel recovery. You don’t need to drive your bodyweight up any more than a couple of pounds per month, but you’ll get the most out of the program when eating in a surplus rather than a deficit. Mistake #3: Starting the Texas Method Too Heavy Coming off the Novice Linear Progression, most lifters are tired, mentally and physically. You probably need a bit of a break for the first week or two before things get super stressful again. Most people stall early on the Texas Method because they plug in their numbers from the end of the Novice LP into the Volume Day of the Texas Method and then set their Intensity Day Numbers somewhere north of that. Really, you should do the opposite. Your Intensity Day (lower volume day) should start somewhere close to where your Novice LP left off, but at a lower volume. Your Volume Days should be somewhere south of that by 1020%. This will allow you to let off the gas pedal a bit for a few weeks with a real and perceived break from extremely stressful loading for a few weeks. Mistake #4: Staying with Only 5-rep Sets Many trainees like the simplicity of the Starting Strength Novice Linear Progression, specifically the fact that you never really have to do anything other than 5-rep sets to drive progress. Many will try to carry this strategy over to their intermediate level training and continue to try and operate off of nothing but 5s. This is a mistake. The mind and body of an Intermediate will require more fluctuation in loading than can be achieved with just a single rep range. In the programs I will present, the intermediate will still get a dose of 5s, but also sets in the 1-4 rep range. This will be necessary for improvements in absolute strength. Training heavier, specifically in the 1-3 range with maximal loads will teach the lifter a very valuable lesson that every strong lifter had to learn at some point….how to strain and grind. New intermediates will often get overwhelmed when handling very heavy loads upwards of 90% of 1RM. Like anything new, it’s a little intimidating. I’ve often seem them quit on sets that could have easily been completed with a little more focus and aggression. Training heavy in the 1-3 rep range is a necessary component of developing physically and mentally as a complete lifter. Don’t avoid it. Basic Texas Method Overview As many of you reading this already know, the Texas Method is basically composed of 3 training days per week, although we often change this to a 4-day split to accommodate the schedules and recovery requirements of certain individuals. Day one is our Volume Day and my basic rule of thumb for volume work is to operate with loads between 75% - 85% of 1RM for a total of 15 to 25 repetitions per exercise. All of the volume work that occurs in my Texas Method programs will adhere to this standard. As a general rule, as we get closer to the high end of the intensity spectrum (85%) the volume will come down (~15 total reps) and the lighter end of the volume spectrum (75%) the volume will increase (~25 total reps). It is important to understand that the loads we use on volume day are only a means to an end, not an end of themselves. While our total volume (tonnage) will increase over time, you may need to regularly recalibrate your loading on volume days to ensure you can still operate efficiently on your Intensity Days. Intensity Days are at the end of the week on a 3-day program and will generally operate between 90% - 100% of 1RM and will utilize 3-6 total repetitions. When using the Texas Method, the goal is to increase our absolute strength which means we are really focused on increasing our performance on the Intensity Day. At the end of several months of Texas Method style programming we are looking for increased performance on our heavy triples, doubles, and singles. On a 3-day plan, we have a recovery day in the middle of the week where we perform light squats, and a light pulling variation. However, we will usually Bench Press or Press fairly heavy on this day, which still makes Recovery Day much easier to recover from than the other two days of the week where everything is heavy. A basic Texas Method Program is below: Monday Squat 5 x 5 Bench Press 5 x 5 SLDL 3 x 5 BB Wednesday Squat 3 x 5 (Light) Press 3-5 x 5 Row or Chin 3 x 8 Friday Squat 2 x 3 Bench press 2 x 3 Deadlift 1 x 3, 1 x 5 This program is just an example, but gives you a basic overview of how a Volume – Recovery – Intensity schedule might look. Note to the Reader (Don’t Skip This!!!) In the program that follows, you will see some differences in what is presented in Practical Programming for Strength Training. This is mainly due to the fact that the program I am providing here is specific rather than the very general models provided in PPST3. Furthermore, the program I am providing here is going to use fairly strict percentages for both volume day and intensity day, something we did not provide in PPST3. Percentage based programs have some pros and cons. The primary drawback to using percentages when training is that there is a chance that the end user will not use an accurate 1-rep max or 1-rep max estimate to base training percentages off of. If the 1RM estimates are too low, the trainee runs the risk of detraining with an inadequate amount of stress in the program. If the 1RM estimates are too high, the trainee will stall within a few weeks because the workloads are too high. If possible, it is best not to “estimate” a 1-rep max if you are not experienced in performing them. There is a high likelihood you’ll overshoot or undershoot your actual capabilities. Prior to beginning any of this program, it’s a good idea to go in on a Friday and take out a heavy single on the Squat, Press or Bench Press, and the Deadlift. These don’t have to be attempts at shattering world records (or shattering yourself) just good solid heavy singles that give you an idea of where you are at in terms of absolute strength. It is NOT imperative that these 1RMs be exact. What we’re trying to avoid are massive miscalculations in either direction. As long as you are in the ballpark within say 5-20 lbs of your actual numbers you’ll be fine. In fact, coming in just a shade light is probably better in the long run anyways. If you cannot or will not test a 1RM on your lifts, you can still find appropriate numbers to plug into your percentages using estimates based off of your best set of 5 reps, which most of you probably know. For most of you, your best single set of 5 (i.e. 5RM) is going to be about 85% of your 1RM. Your best 3x5 maximum will be about 80% of your 1RM. These numbers may not be exact for everyone, but they will be close enough for you to plug into the program and get a decent starting place for the first training cycle. Once you get that first training cycle under your belt, the percentages won’t matter as much. You’ll just be basing increases off of the previous cycle. But we do need a good starting point for the first cycle so we don’t have any missteps right from the get go. This is imperative to long term success on these programs. Volume Cycling Another difference you’ll see from PPST3 is the inclusion of Volume Cycling. This is something I have been doing in recent years with clients running Texas Method style programming and I believe it to be optimal for long term usage of the program for most trainees. This essentially fluctuates the stress load over the course of a 3-week cycle on the volume day, and in my observation, prevents the cycle of stalling / resetting that can make long term programming complicated, especially in the absence of an experienced coach who can help guide you through the process of stalls and resets. Volume Cycling will essentially look like this: Week 1: 5 x 5 @ 75% Week 2: 5 x 4 @ 80% Week 3: 5 x 3 @ 85% Week 4: 5 x 5 (2-5 lbs more than Week 1) Week 5: 5 x 4 (2-5 lbs more than Week 2) Week 6: 5 x 3 (2-5 lbs more than Week 3) Most will find that this variation in workload week to week easier to manage than staying with a static workload (like 5x5) and progressing linearly in perpetuity. Specialization I also recommend that trainees using the Texas Method specialize in either the Bench Press or the Press. This tends to work better than alternating the focus week to week on one lift or the other. For most trainees, I will recommend that they focus on the Bench Press and train that lift on the Volume Day and the Intensity Day, while training the Press on the Recovery Day. Gains on the Bench Press will have a carryover to the Press more so than the other way around. You may choose to swap this focus around at a later date, but in general, I don’t recommend trying to alternate the focus week to week. 3-Day Texas Method (Bench Press Focus) Week One Monday: Volume Day Squat 5 x 5 @ 75% of 1RM Bench Press 5 x 5 @ 75% of 1RM Stiff Leg Deadlift 5 x 5 @ 60% of Deadlift 1RM (perform from floor or while standing on 2-4” deficit for increase range of motion and hamstring recruitment). GPP Superset: Light Posterior Chain 3 x 10-20 (Glute Ham Raise, 45 or 90 degree Back Extensions, Reverse Hypers); Abdominals 3 x 10-20 (decline or ghd sit ups, hanging or lying leg raise, ab wheel). Wednesday: Recovery Day Squat 3 x 5 @ 60% of 1RM Press 5 x 5 @ 75% of 1RM Chins 3-5 x 8-10 Conditioning: 20 minutes of sled pulling, sled pushing, stationary bike, resisted elliptical, or incline treadmill walking Friday: Intensity Day Squat 2 x 3 (2 sets of 3 reps) @ 85% of 1RM Bench Press 2 x 3 @ 85% of 1RM Deadlift 1 x 3 @ 85% of 1RM; 1 x 5 @ 75% of 1RM (back off set) Dips 3-5 x 8-10 Saturday: Conditioning 20-40 minutes of sled pulling, sled pushing, stationary bike, resisted elliptical, or incline treadmill walking Week Two Monday: Volume Day Squat 5 x 4 (5 sets of 4 reps) @ 80% of 1RM Bench Press 5 x 4 @ 80% of 1RM Stiff Leg Deadlift 4 x 5 (4 sets of 5 reps) @ 65% of Deadlift 1RM (perform from floor or while standing on 2-4” deficit for increase range of motion and hamstring recruitment). GPP Superset: Light Posterior Chain 3 x 10-20 (Glute Ham Raise, 45 or 90 degree Back Extensions, Reverse Hypers); Abdominals 3 x 10-20 (decline or ghd sit ups, hanging or lying leg raise, ab wheel). Wednesday: Recovery Day Squat 3 x 5 @ 65% of 1RM Press 5 x 4 @ 80% of 1RM Chins 3-5 x 8-10 Conditioning: 20 minutes of sled pulling, sled pushing, stationary bike, resisted elliptical, or incline treadmill walking Friday: Intensity Day Squat 2-3 x 2 (2-3 sets of 2 reps) @ 90% of 1RM Bench Press 2-3 x 2 @ 90% of 1RM Deadlift 1 x 2 @ 90% of 1RM; 1 x 4-5 @ 80% of 1RM (back off set) Dips 3-5 x 8-10 Saturday: Conditioning 20-40 minutes of sled pulling, sled pushing, stationary bike, resisted elliptical, or incline treadmill walking Week Three Monday: Volume Day Squat 5 x 3 (5 sets of 3 reps) @ 85% of 1RM Bench Press 5 x 3 @ 85% of 1RM Stiff Leg Deadlift 3 x 5 (3 sets of 5 reps) @ 70% of Deadlift 1RM (perform from floor or while standing on 2-4” deficit for increase range of motion and hamstring recruitment). GPP Superset: Light Posterior Chain 3 x 10-20 (Glute Ham Raise, 45 or 90 degree Back Extensions, Reverse Hypers); Abdominals 3 x 10-20 (decline or ghd sit ups, hanging or lying leg raise, ab wheel). Wednesday: Recovery Day Squat 3 x 5 @ 70% of 1RM Press 5 x 3 @ 85% of 1RM Chins 3-5 x 8-10 Conditioning: 20 minutes of sled pulling, sled pushing, stationary bike, resisted elliptical, or incline treadmill walking Friday: Intensity Day Squat 3 x 1 (3 sets of 1 rep) @ 95% of 1RM Bench Press 3-5 x 1 @ 95% of 1RM Deadlift 1 x 1 @ 95% of 1RM; 1 x 3-5 @ 85% of 1RM (back off set) Dips 3-5 x 8-10 Saturday: Conditioning 20-40 minutes of sled pulling, sled pushing, stationary bike, resisted elliptical, or incline treadmill walking Week Four Monday: Volume Day Squat 5 x 5 @ +5 lbs from Week 1 Bench Press 5 x 5 @ +2-5 lbs from Week 1 Stiff Leg Deadlift 5 x 5 @ +5 lbs from Week 1 (perform from floor or while standing on 2-4” deficit for increase range of motion and hamstring recruitment). GPP Superset: Light Posterior Chain 3 x 10-20 (Glute Ham Raise, 45 or 90 degree Back Extensions, Reverse Hypers); Abdominals 3 x 10-20 (decline or ghd sit ups, hanging or lying leg raise, ab wheel). Wednesday: Recovery Day Squat 3 x 5 @ 60% of 1RM Press 5 x 5 @ +2-5 lbs from Week 1 Chins 3-5 x 8-10 Conditioning: 20 minutes of sled pulling, sled pushing, stationary bike, resisted elliptical, or incline treadmill walking Friday: Intensity Day Squat 2 x 3 @ +5 lbs from Week 1 Bench Press 2 x 3 @ + 2-5 lbs from Week 1 Deadlift 1 x 3 @ + 5 lbs from Week 1; 1 x 5 @ + 5 lbs from Week 1 Dips 3-5 x 8-10 Saturday: Conditioning 20-40 minutes of sled pulling, sled pushing, stationary bike, resisted elliptical, or incline treadmill walking Week Five Monday: Volume Day Squat 5 x 4 @ + 5 lbs from Week 2 Bench Press 5 x 4 @ + 2-5 lbs from Week 2 Stiff Leg Deadlift 4 x 5 @ + 5 lbs from Week 2 (perform from floor or while standing on 2-4” deficit for increase range of motion and hamstring recruitment). GPP Superset: Light Posterior Chain 3 x 10-20 (Glute Ham Raise, 45 or 90 degree Back Extensions, Reverse Hypers); Abdominals 3 x 10-20 (decline or ghd sit ups, hanging or lying leg raise, ab wheel). Wednesday: Recovery Day Squat 3 x 5 @ 65% of 1RM Press 5 x 4 @ + 2-5 lbs from Week 2 Chins 3-5 x 8-10 Conditioning: 20 minutes of sled pulling, sled pushing, stationary bike, resisted elliptical, or incline treadmill walking Friday: Intensity Day Squat 2-3 x 2 @ + 5 lbs from Week 2 Bench Press 2-3 x 2 @ + 2-5 lbs from Week 2 Deadlift 1 x 2 @ + 5 lbs from Week 2; 1 x 4-5 @ + 5 lbs from Week 2 Dips 3-5 x 8-10 Saturday: Conditioning 20-40 minutes of sled pulling, sled pushing, stationary bike, resisted elliptical, or incline treadmill walking Week Six Monday: Volume Day Squat 5 x 3 @ + 5 lbs from Week 3 Bench Press 5 x 3 @ + 2-5 lbs from Week 3 Stiff Leg Deadlift 3 x 5 @ + 5 lbs from Week 3 (perform from floor or while standing on 2-4” deficit for increase range of motion and hamstring recruitment). GPP Superset: Light Posterior Chain 3 x 10-20 (Glute Ham Raise, 45 or 90 degree Back Extensions, Reverse Hypers); Abdominals 3 x 10-20 (decline or ghd sit ups, hanging or lying leg raise, ab wheel). Wednesday: Recovery Day Squat 3 x 5 @ 70%% of 1RM Press 5 x 3 @ + 2-5 lbs from Week 3 Chins 3-5 x 8-10 Conditioning: 20 minutes of sled pulling, sled pushing, stationary bike, resisted elliptical, or incline treadmill walking Friday: Intensity Day Squat 3 x 1 @ + 5 lbs from Week 3 Bench Press 3-5 x 1 @ + 2-5 lbs from Week 3 Deadlift 1 x 1 @ + 5 lbs from Week 3; 1 x 3-5 @ + 5 lbs from Week 3 Dips 3-5 x 8-10 Saturday: Conditioning 20-40 minutes of sled pulling, sled pushing, stationary bike, resisted elliptical, or incline treadmill walking The preceding was a 6 week “snapshot” of the first two cycles of training on this plan. The first 3-week cycle starts with fixed percentages to establish a correct starting point and appropriate offsets from day to day and week to week. Cycle 2 eliminates the fixed percentages and work set loads are determined based off the previous 3-week cycle. Below is a sample 9 week progression (Three 3-week cycles) for a hypothetical lifter with the following 1RMs: Squat 375 x 1 Bench Press 305 x 1 Deadlift 450 x 1 Press 205 x 1 Week 1 Monday: Volume Day Squat 5 x 5 x 280 (75%) Bench Press 5 x 5 x 230 (75%) Stiff Leg Deadlift 5 x 5 x 270 (60%) Wednesday: Recovery Day Squat 3 x 5 x 225 Press 5 x 5 x 155 Friday: Intensity Day Squat 2 x 3 x 320 (85%) Bench Press 2 x 3 x 260 (85%) Deadlift 1 x 3 x 380 (85%); 1 x 5 x 335 (75%) Week 2 Monday: Volume Day Squat 5 x 4 x 300 (80%) Bench Press 5 x 4 x 245 (80%) Stiff Leg Deadlift 4 x 5 x 290 (65%) Wednesday: Recovery Day Squat 3 x 5 x 245 (65%) Press 5 x 4 x 165 (80%) Friday: Intensity Day Squat 2-3 x 2 x 335 (90%) Bench Press 2-3 x 2 x 275 (90%) Deadlift 1 x 2 x 405 (90%), 1 x 4-5 x 360 (80%) Week 3 Monday: Volume Day Squat 5 x 3 x 320 (85%) Bench Press 5 x 3 x 260 (85%) Stiff Leg Deadlift 3 x 5 x 315 (70%) Wednesday: Recovery Day Squat 3 x 5 x 260 (70%) Press 5 x 3 x 175 (85%) Friday: Intensity Day Squat 3 x 1 x 355 (95%) Bench Press 3-5 x 1 x 290 (95%) Deadlift 1 x 1 x 430 (95%); 1 x 3-5 x 380 (85%) Week 4 Monday: Volume Day Squat 5 x 5 x 285 Bench Press 5 x 5 x 235 Stiff Leg Deadlift 5 x 5 x 275 Wednesday: Recovery Day Squat 3 x 5 x 230 Press 5 x 5 x 160 Friday: Intensity Day Squat 2 x 3 x 325 Bench Press 2 x 3 x 265 Deadlift 1 x 3 x 385; 1 x 5 x 340 Week 5 Monday: Volume Day Squat 5 x 4 x 305 Bench Press 5 x 4 x 250 Stiff Leg Deadlift 4 x 5 x 295 Wednesday: Recovery Day Squat 3 x 5 x 250 Press 5 x 4 x 170 Friday: Intensity Day Squat 2-3 x 2 x 340 Bench Press 2-3 x 2 x 280 Deadlift 1 x 2 x 410, 1 x 4-5 x 365 Week 6 Monday: Volume Day Squat 5 x 3 x 325 Bench Press 5 x 3 x 265 Stiff Leg Deadlift 3 x 5 x 320 Wednesday: Recovery Day Squat 3 x 5 x 265 Press 5 x 3 x 180 Friday: Intensity Day Squat 3 x 1 x 360 Bench Press 3-5 x 1 x 295 Deadlift 1 x 1 x 435; 1 x 3-5 x 385 Week 7 Monday: Volume Day Squat 5 x 5 x 290 Bench Press 5 x 5 x 240 Stiff Leg Deadlift 5 x 5 x 280 Wednesday: Recovery Day Squat 3 x 5 x 235 Press 5 x 5 x 165 Friday: Intensity Day Squat 2 x 3 x 330 Bench Press 2 x 3 x 270 Deadlift 1 x 3 x 390; 1 x 5 x 345 Week 8 Monday: Volume Day Squat 5 x 4 x 310 Bench Press 5 x 4 x 255 Stiff Leg Deadlift 4 x 5 x 300 Wednesday: Recovery Day Squat 3 x 5 x 255 Press 5 x 4 x 175 Friday: Intensity Day Squat 2-3 x 2 x 345 Bench Press 2-3 x 2 x 285 Deadlift 1 x 2 x 415, 1 x 4-5 x 370 Week 9 Monday: Volume Day Squat 5 x 3 x 330 Bench Press 5 x 3 x 270 Stiff Leg Deadlift 3 x 5 x 325 Wednesday: Recovery Day Squat 3 x 5 x 270 Press 5 x 3 x 185 Friday: Intensity Day Squat 3 x 1 x 365 Bench Press 3-5 x 1 x 300 Deadlift 1 x 1 x 440; 1 x 3-5 x 390 Frequently Asked Questions (Don’t Skip This!) 1. Do I have to do the GPP / Conditioning / Assistance exercises or can I just stick to the basic barbell lifts? No, they are not all 100% mandatory, but they are recommended. You will have better success on the Texas Method when your work capacity or General Physical Preparedness (GPP) is higher. This is a physical quality that must be trained separate and apart from just doing the workouts. In other words you are getting/keeping yourself in shape enough to train. When your work capacity or GPP is higher you will have better recovery within each workout (i.e. faster recovery between sets) and between workouts. The lighter workouts for the posterior chain and abs will increase your ability to tolerate pulling volume. The conditioning work will build a base of aerobic/anaerobic fitness that will also lend itself to faster recovery, better partitioning of calories, etc. I do NOT recommend that you kill yourself with the intensity of the conditioning workouts. Go hard, work up a good sweat, get your heart rate up, but don’t beat yourself up too badly. The Dips and Chins are just a good idea for some upper body training volume since most everything is being trained with very low reps. Both exercises will help you build muscle mass and create a more balanced physique while getting stronger on the barbell movements. Sled work is recommended for conditioning as this essentially serves to take the place of any lower body assistance type work and covers your cardio training. 2. How long should I rest between sets? As long as you need but no longer. If you find that the volume day sets are not terribly challenging the first few times through a cycle then push the pace. This will serve to build your conditioning and better enable you to get through the workouts as the loads increase. Increased rest time can be a variable you manipulate down the road to get through heavier workouts. A good middle ground for heavy work sets is about 5 minutes. If you need longer, you can take up to 8 minutes, but no longer. If you can complete work sets on less than 5 minutes of rest you should try to. Just don’t have missed reps because you are going too fast. If you find that you are wanting to take 8 minutes or more between all of your sets, then you should really focus on the two weekly conditioning sessions, with an emphasis on sled dragging or sled pushing. On Chins and Dips I recommend a 2-3 minute rest period, on the super sets for the posterior chain and abs you should take no rest between exercises. 3. Should I add more assistance work than this? If you do, not much more. Perhaps some biceps for cosmetic purposes on Friday, possibly supersetted with Dips for 3-5 sets of 8-10. Other than that you won’t need much if you are training hard enough. 4. What if the first few cycles are too easy? If they are incredibly easy, then you might just want to bump up your estimated 1RM starting in the second 3-week cycle. Just be careful with this. Underestimating your 1RM is better than overestimating. It gets harder very quickly. And I have found that greater long term progress comes when you start a little light and build up your tolerance to the workload over a few cycles. There are a few “tricks” you can use however to make lighter weights feel more challenging. First is paused reps. This works well on Squats and Bench Presses. You can pause some or all of your reps for a 2-5 second count and this will increase the effectiveness of a submaximal load. As loads increase over time you can remove the pauses. Second is bar speed, often in combination with paused reps. In other words, pause the weight and then EXPLODE the weight up with maximal velocity and acceleration. This will increase force production. For Bench Presses you can also narrow your grip and perform some or all of your sets with a close grip if the weights feel very light. Close Grips carry over well to regular bench presses later on. Widen your grip out as weights increase over time. For Deadlifts, you may choose to perform your back off set as a Deficit Deadlift standing on a platform approximately ~2 inches in height. Also, some trainees prefer to perform their Deadlift back off set for max reps – often going as high as 8-reps if they feel strong that day. 5. I want to do Power Cleans instead of Stiff Leg Deadlifts You can, but for most people doing this program, the Power Clean will not provide an adequate training stress to move the Deadlift along. If you choose to Power Clean, you’ll likely need to increase the volume of Deadlifts you perform on Friday. 6. Can I perform this routine on a 4-day Split rather than a 3-day Split? Yes. I prefer the split to look like this if you do so: Monday – Bench Press Intensity + Press Volume Tuesday – Squat Intensity + Deadlift Intensity Thursday – Bench Press Volume + Dips + Chins Friday – Squat Volume + Stiff Leg Deadlifts All percentages, sets/reps, etc will stay the same. 7. When do I take a Deload? As an intermediate I prescribe Deloads “as needed”. You can take a deload after any of the 3-week cycles, preferably you will train in 6-12 week blocks before you require a deload of any sort. When you deload, schedule your week like this: Monday: Squat 3 x 5 @ 75%, Bench Press 3 x 5 @ 75%, Stiff Leg Deadlifts – 3 x 5 @ 60% Wednesday: Squat 3 x 5 @ 65%, Press 3 x 5 @ 75%, Chins 3 x 8-10 Friday: Squat 1 x 3 @ 85%, Bench 1 x 3 @ 85%, Deadlift 1 x 3 @ 80% or Omit. Percentages don’t have to be exact for the Deload. Basically just lower the volume across the board and train with moderate loads 8. What if I miss a workout? For just a single workout, you might just choose to skip it and move on. As long as it’s not a routine, a missed workout here or there will not destroy your program. If you can reschedule your week to get in all your training days (especially the volume and intensity day) this is ideal. If you miss an entire week of training, try and come back to repeat the missed week as prescribed and then carry forward. If you miss 2+ weeks of training you probably need to recalibrate your 1RM estimates downward a bit and start the program over with slightly lowered weights. If you have a very sporadic schedule that doesn’t allow for consistent training, then you might be better suited with something other than the Texas Method. 9. What if a single lift gets stuck and isn’t progressing? If you are simply stagnate (just not improving) then the problem is usually an insufficient volume to drive you forward. You might try increasing the loading on your volume day if those weights feel light. So maybe make a 10 lb jump between cycles instead of 5 lbs. You could also add in 1-2 back off sets on the Intensity Day for 1-2 x 5 after your heavy 1s, 2s, or 3s. Often with Presses, I will have my trainee perform 1-2 back off sets of ~8 reps following their 5 main work sets in the 3-5 range if Presses get stuck. If you begin to REGRESS on a given lift, it’s usually a sign of over training that lift. Back off the volume a bit or lower the loading a bit on the volume day. The KSC Method for RAW Power Lifting A complete 7-week training cycle for competitive or non-competitive power lifting training. Can be used to peak for your next power lifting meet or simply to build a bigger squat, bench press, and deadlift. Also included is a 7-week training cycle for competitive or non-competitive strengthlifting training for your next strength lifting competition or simply to build a bigger squat, overhead press, and deadlift. This is a 4-day per week program but can be tailored for 3-day per week use for lifters with limited time or recovery. The program is an upper/lower split structured similarly to the traditional 4-day Texas Method, but easier to recover from than most Texas Method programs. Appropriate for lifters of any age. The 7-week cycle can be repeated for multiple cycles for long term usage. Includes a template for bodybuilding style assistance exercises to help build muscle mass and strengthen weak points in all your lifts. The following program is a simple 7-week repeatable cycle that can be used for competitive or non-competitive power lifting training. The program can also be used for competitive or non-competitive strength lifting training which is similar to power lifting but consists of the Squat, Deadlift, and Overhead Press instead of the Bench Press as the focus lifts of the program. Whether you choose to prioritize power lifting or strength lifting, you can still effectively train and progress both the Bench Press and Overhead Press if progress on both lifts is important to you. The program is set up to be a 4-day per week program, but it can be manipulated into a 3day per week program if you feel you need an extra day of recovery each week or if scheduling issues prevent you from getting to the gym 4 days per week. Over the course of the program you will do a combination of very heavy training on all the competitive lifts in the 1‐3 rep range, at or above 90% of 1RM. You will also be exposed to high volume loading in the 75-85% range on all the competitive lifts. Additionally, on certain weeks you will be prescribed to perform certain variations of the competitive lifts for a moderate volume and intensity scheme to help you build muscle mass and work on weak points. However, the key to making this work is that not all of these methods are used every week for every lift. Attempting to do so will lead to burn out and overtraining. Over the course of 7-weeks there will be a cycling of volume, intensity, and exercise selection that will leave you feeling fresh at every training session so that you can attack the volume and intensity workouts with vigor and focus. The first 6 weeks of the program are your “loading weeks” where we will build up your capacity on all your competitive lifts and some key assistance lifts and in Week 7 you will sharply deload from both volume and intensity and all assistance work. If you have a competition planned, you will insert the meet onto the end of Week 7. If you do not have a competition planned then you will continue to rest and train with light workouts and then start the program all over again the following week. This is a tried and true program and you do not need to adjust training percentages or exercise selection, except for maybe on some of the non-essential assistance movements I recommend. You will be provided templates to follow for competitive training and non-competitive training as the insertion of a meet into Week 7 will heavily influence how you re-start the subsequent training cycle. Let’s get started! Squat Training As with any good training program, your success or lack thereof, is largely predicated on squat performance. Not only is the squat 1/3 of your total in a power lifting or strength lifting meet, but it also drives your performance on the deadlift. It is very important that all of your intensity day and volume day workouts be done with the exact style of squat that you will use in competition. The preferred method is the low-‐‐bar back squat as described in Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training. If you cannot low-‐‐bar squat due to age or old injury then a high bar back squat will have to suffice, but low-‐‐bar is superior in terms of weight that can be lifted and the amount of muscle mass you can train. Three times during the cycle you will be prescribed “light squats” in the 60-70% range. These are moderate in load and volume and are simply used to “grease the groove” and maintain your squat form on lower body workouts where we are more focused on the deadlift. However, if you feel you don’t need to “grease the groove” of your competition squat form then you can substitute light squats with a variation of the squat. Acceptable substitutes include the front squat, the pause squat, pin squats, box squats, or squats with a specialty bar such as a safety squat bar or cambered bar. Different variations of the squat can be used to help strengthen weak points in your lift or simply introduce some variety into the programming in order to break up the monotony. My recommendation is that less experienced lifters use the basic “light squat” to practice their technique and that more experienced lifters who don’t have any significant technique issues can select a variation of the squat that helps to strengthen a weak point in their lifts. However, the first time through the program I recommend everyone simply do the light squat instead of a squat variation. If you choose a variation of the squat for your light day, you will do so with an equivalent volume to what is prescribed in the program, but the percentages will not apply. For example, if a light squat is prescribed for 3x5@60% and you choose a paused box squat as a substitution then you will simply select a load that can be done for 3 sets of 5 reps without any missed reps. If you don’t know how to select an appropriate load “on the fly” then you probably just need to stick to light squats at the prescribed percentages. Additionaly, you can tweak the set/rep range to fit the movement. So if front squats are chosen for your light day, you might just do 3-5 sets of 3 reps rather than 5 reps as triples are more appropriate for front squats than are sets of 5 due to the difficulty of keeping a heavy front squat racked for a prolonged period of time. Deadlift Training The deadlift will follow a similar cycle as the squats for high intensity workouts (1‐3 reps at or above 90% of 1RM) but there will not be a dedicated high volume deadlift workout. You will be dependent on the stress created by your high volume squat workout to help move your deadlifts along. Instead we will use a series of back off sets following your high intensity deadlift sessions as well as variations of the deadlift following some of your squat workouts. Recovery from deadlifts tends to be a somewhat individualized factor and not everyone can necessarily perform the same volume of deadlifts during the training cycle. You will have to use a little bit of instinct, experience, and common sense to decipher how much of the deadlift volume you want to try and do. It is recommended that you do the maximum amount of work you are capable of during each 6 week loading block as it will make the effects of the week 7 deload al that much more effective. Bench Press & Overhead Press Training The Bench Press and Overhead Press follow a very similar cycle to the Squat for volume and intensity work. If you are competing for power lifting then all volume work will be done with the bench press. On intensity days you will bench press at 90% or above every other week. On alternate weeks you will select a bench press variation such as a close grip bench press to use for your heavy lifts OR you can train the press heavy on these days if you still want some focus on that lift. The template I prescribe here uses the close grip bench press on alternate days of the bench press for the powerlifting program. Overhead presses are used for assistance work after your volume benches. If you are competing in strength lifting, then all volume work will be done with the overhead press. On intensity days you will train the press at 90% or above every other week and on alternate weeks it is suggested that you train either the bench press or incline bench press as your other heavy lift on alternate weeks from the overhead press. There will also be a mix of some targeted higher rep back off sets and some assistance exercises for you to choose from. These will help to build muscle mass and address weak points in your lift, especial y the triceps which play a major role in benching or overhead pressing. How to Start the Program Often, when a trainee starts a new program it is because they are burnt out or overtrained from a previous program they were using that was not yielding results. If this is the case with you, it is suggested that you take 1-2 light weeks in the gym prior to starting this program. Simply train a light full body workout twice per week with a moderate volume and load (ex: 3x5@70%) for the squat and the bench press or overhead press and a single set of 5 deadlifts. This should allow some fatigue to dissipate from your system without letting yourself completely detrain. If you have not been training or have not been training consistently then you can start the program as prescribed when you are ready. 4-Day Per Week – Power Lifting Focus Week One Monday – Bench Intensity / Testing 1. Bench Press – work up to a 1-rep max on the bench press. Try and avoid missed reps if possible. Once you achieve your max single for the day, move on to exercise 2. 2. Flat or Incline Dumbbell Bench Press: 3‐5 sets of 8‐10 reps. Rest 2‐3 minutes between sets, use a full range of motion. 3. Triceps Extensions: 3-5 sets of 10-15 reps. Tuesday – Squat Intensity / Testing 1. Back Squat – work up to a 1-rep max on the squat. Try and avoid missed reps if possible. Once you achieve your max single for the day, move on to exercise 2 2. Rack Pull – work up to a conservative set of 5 reps. Rest 3‐5 minutes, deload the bar by 10% and perform a second set of 8-10 reps 3. Barbell Rows 3‐5 sets of 8‐10. Rest 2‐3 minutes between sets. Thursday – Bench Press Volume 1. Bench Press – after warm ups, perform 5 x 5 @ 75% of Monday’s 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Overhead Press – after warm ups perform 3 sets of 6‐8 reps + 1 set of 10‐12 reps 3. Triceps Extensions – 3-5 sets of 10-15 reps Friday – Squat Volume 1. Back Squat – after warm ups, perform 5 x 5 @ 75% of Monday’s 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Stiff Leg Deadlift – 2-3 sets of 6 reps. 3. Chin Ups or Pull Ups – 3-5 sets of max reps or Pulldowns 3-5 sets of 8-10 Week Two Monday – Bench Intensity 1. Close Grip Bench Press – work up to a 1‐rep max on the close grip bench press. Try and avoid missed reps if possible. Once you achieve your max single for the day, then perform 3 sets of 5-8 reps at 75% of 1RM and 1 set of 8-12 reps at 60% of 1RM. Rest as needed between sets 2. Dips - 5 sets of max reps (aim for minimum of 25 total reps) Tuesday – Deadlift Intensity / Testing 1. Light Squat – 3 x 5 @ 60% of 1RM 2. Deadlifts – work up to a 1-rep max on the deadlift. Try and avoid missed reps if possible. Once you achieve your max single for the day perform a set for maximal reps at 75% of 1RM. You may use lifting straps for the back off set. 3. One Arm DB Rows or Seated Rows 3‐5 sets of 8-10. Rest 2-3 minutes between sets. Thursday – Bench Press Volume 1. Bench Press – after warm ups, perform 5 x 4 or 4 x 5 @ 80% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Overhead Press – after warm ups perform 3 sets of 5‐7 reps + 1 set of 10‐12 reps 3. Triceps Extensions – 3-5 sets of 10-15 reps Friday – Squat Volume 1. Back Squat – after warm ups, perform 5 x 4 or 4 x 5 @ 80% of Monday’s 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Stiff Leg Deadlift – 2‐3 sets of 5 reps. 3. Chin Ups or Pull Ups – 3‐5 sets of max reps or Pulldowns 3-5 sets of 8-10 Week Three Monday – Bench Intensity 1. Bench Press – after warm ups, perform 3 x 3 or 4 x 2 @ 90% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Flat or Incline Dumbbell Bench Press: 3‐5 sets of 8-10 reps. Rest 2‐3 minutes between sets, use a full range of motion. 3. Triceps Extensions: 3-5 sets of 10-15 reps. Tuesday – Squat Intensity 1. Back Squat – after warm ups, perform 3 x 3 or 4 x 2 @ 90% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Rack Pull – perform a set of 5 reps with 5-20 lbs. more than you used in week 1. Deload the bar by 10% and perform a set of 8-10 reps. 3. Barbell Rows 3-5 sets of 8-10. Rest 2-3 minutes between sets. Thursday – Bench Press Volume 1. Bench Press – after warm ups, perform 5 x 3 (5 sets of 3) or 4 x 4 @ 85% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Overhead Press – after warm ups perform 3 sets of 4‐6 reps + 1 set of 10-12 reps 3. Triceps Extensions – 3‐5 sets of 10‐15 reps Friday – Squat Volume 1. Back Squat – after warm ups, perform 5 x 3 or 4 x 4 @ 85% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Stiff Leg Deadlift – 2‐3 sets of 4 reps. 3. Chin Ups or Pull Ups – 3-5 sets of max reps or Pulldowns 3-5 sets of 8-10 Week Four Monday – Bench Intensity 1. Close Grip Bench Press – after warm ups, perform 3 sets of 2-3 reps with 90% of your week two 1RM. Then back off to 80% of 1RM and perform 1 set of max reps. Then back off to 65% and perform 1 set of max reps. (Example: 1RM = 275. 3x3x250, 1xMaxRepsx220, 1xMaxRepsx180) Rest as needed between sets 2. Dips - 5 sets of max reps (aim for minimum of 25 total reps) Tuesday – Deadlift Intensity 1. Light Squat – 3 x 5 @ 65% of 1RM 2. Deadlifts – after warm ups, perform one max set at 90% of your week 2 1RM (2‐4 reps). Then, deload the bar to 80% of 1RM and perform a second max set of 5-‐‐8 reps. Rest as needed between sets. 3. One Arm DB Rows or Seated Rows 3-5 sets of 8-‐‐10. Rest 2-3 minutes between sets. Thursday – Bench Press Volume 1. Bench Press – after warm ups, perform 5 x 6 @ 75% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume (5 sets, 6 reps) 4. Overhead Press – after warm ups perform 3 sets of 6-‐‐8 reps + 1 set of 10-‐‐12 reps. Try and beat what you previously did for 6-8 reps in week 1 by either adding weight or adding reps. 5. Tricep Extensions – 3‐5 sets of 10‐15 reps Friday – Squat Volume 1. Back Squat – after warm ups, perform 5 x 6 @ 75% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume. 2. Stiff Leg Deadlift – 2‐3 sets of 6 reps. Try and beat what you did in week 1 for sets of 6. 3. Chin Ups or Pull Ups – 3-5 sets of max reps or Pulldowns 3-5 sets of 8‐10 Week Five Monday – Bench Intensity 1. Bench Press – after warm ups, perform 3 x 2 or 6 x 1 @ 95% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Flat or Incline Dumbbell Bench Press: 3‐5 sets of 8‐10 reps. Rest 2‐3 minutes between sets, use a full range of motion. 3. Triceps Extensions: 3‐5 sets of 10‐15 reps. Tuesday – Squat Intensity 1. Back Squat – after warm ups, perform 3 x 2 or 6 x 1 @ 95% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume (3 sets of 2 or 6 sets of 1) 2. Rack Pull – perform a set of 5 reps with 5-20 lbs more than you used in week 3. Deload the bar by 10% and perform a set of 8-10 reps. 3. Barbell Rows 3-5 sets of 8-10. Rest 2-3 minutes between sets. Thursday – Bench Press Volume 1. Bench Press – after warm ups, perform 5 x 5 or 6 x 4 @ 80% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume (5 sets of 5 or 6 sets of 4) 2. Overhead Press – after warm ups perform 3 sets of 5‐7 reps + 1 set of 10‐12 reps. Try and beat what you did in week 2 for sets of 5‐7 by either adding weight or adding reps. 3. Triceps Extensions – 3-5 sets of 10-15 reps Friday – Squat Volume 1. Back Squat – after warm ups, perform 5 x 5 or 6 x 4 @ 80% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Stiff Leg Deadlift – 2‐3 sets of 5 reps. Try and beat what you did in week 2 for sets of 5 reps. 3. Chin Ups or Pull Ups – 3-5 sets of max reps or Pul downs 3-5 sets of 8-10 Week Six Monday – Bench Intensity 1. Close Grip Bench Press – after warm ups, perform 3 x 2 reps or 6 x 1 with 95% of your week two 1RM. Then back off to 85% of 1RM and perform 1 set of max reps. Then back off to 70% and perform 1 set of max reps. (Example: 1RM = 275. 3x2x260, 1xMaxRepsx235, 1xMaxRepsx190) Rest as needed between sets 3. Dips - 5 sets of max reps (aim for minimum of 25 total reps) Tuesday – Deadlift Intensity 1. Light Squat – 3 x 5 @ 70% of 1RM 2. Deadlifts – after warm ups, perform one max set at 95% of your week 2 1RM (2-3 reps). Then, deload the bar to 85% of 1RM and perform a second max set of 3-6 reps. Rest as needed between sets. 3. One Arm DB Rows or Seated Rows 3-5 sets of 8-10. Rest 2-3 minutes between sets. Thursday – Bench Press Volume 1. Bench Press – after warm ups, perform 5 x 4 or 6 x 3 @ 85% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume (5 sets of 4 or 6 sets of 3) 2. Overhead Press – after warm ups perform 3 sets of 3‐5 reps + 1 set of 10-12 reps. 3. Triceps Extensions – 3‐5 sets of 10-15 reps Friday – Squat Volume 1. Back Squat – after warm ups, perform 5 x 4 or 6 x 3 @ 85% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume. 4. Stiff Leg Deadlift – 2-3 sets of 4 reps. Try and beat what you did in week 3 for sets of 4. 5. Chin Ups or Pull Ups – 3-5 sets of max reps or Pulldowns 3-5 sets of 8-10 Week 7 (Deload + Power Lifting Meet) Tuesday – Squat & Bench Deload 1. Back Squat 3 x 3 @ 75% of 1RM 2. Bench Press 3 x 3 @ 75% of 1RM Saturday – MEET Recommended Meet Strategy: a. Attempt #1: Open with 90%-‐‐95% of your week one 1RM b. Attempt #2: Attempt a 5% increase from your week one 1RM (est. 10‐20 lbs) c. Attempt #3: Attempt an increase from Attempt #2 based on feel (est. 5-20 lbs) Week 7 Deload (No Meet) Tuesday – Squat & Bench Deload 1. Back Squat 3 x 3 @ 70% of 1RM 2. Bench Press 3 x 3 @ 70% of 1RM Friday – Squat, Bench, Deadlift Deload 1. Back Squat 3 x 3 @ 75% of 1RM 2. Bench Press 3 x 3 @ 75% of 1RM 3. Deadlift 1 x 3 @ 75% of 1RM Post Meet Note If you want to restart the training cycle immediately following your power lifting meet, then you can skip the testing days altogether in week 1. Take 3‐4 days of complete rest following your meet and resume training on Thursday and Friday with your volume workouts for Bench & Squat at 75%. In Week 2 you can skip the Deadlift 1RM attempt on Tuesday and simply perform the volume work at 1 set of max reps @75% as prescribed. All % work in your immediate post meet training cycle will be based off your best lifts at the meet. 4-Day Per Week – Strength Lifting Focus (Squat & Deadlift workouts are the same as the Power Lifting Program) Week One Monday – Overhead Press Intensity / Testing 1. Overhead Press – work up to a 1-‐‐rep max on the overhead press. Try and avoid missed reps if possible. Once you achieve your max single for the day, move on to exercise 2. 2. Seated Dumbbell Press: 3-5 sets of 8-10 reps. Rest 2-3 minutes between sets, use a full range of motion. 3. Triceps Extensions: 3-5 sets of 10-15 reps. Tuesday – Squat Intensity / Testing 1. Back Squat – work up to a 1‐rep max on the squat. Try and avoid missed reps if possible. Once you achieve your max single for the day, move on to exercise 2 2. Rack Pull – work up to a conservative set of 5 reps. Rest 3-5 minutes, deload the bar by 10% and perform a second set of 8‐10 reps 3. Barbell Rows 3-5 sets of 8‐10. Rest 2‐3 minutes between sets. Thursday – Overhead Press Volume 1. Overhead Press – after warm ups, perform 5 x 5 @ 75% of Monday’s 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Close Grip Bench Press – after warm ups perform 3 sets of 6-8 reps + 1 set of 10-12 reps 3. Triceps Extensions – 3-5 sets of 10-15 reps Friday – Squat Volume 1. Back Squat – after warm ups, perform 5 x 5 @ 75% of Monday’s 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Stiff Leg Deadlift – 2-3 sets of 6 reps. 3. Chin Ups or Pull Ups – 3-5 sets of max reps or Pulldowns 3-5 sets of 8-10 Week Two Monday – Bench Press Intensity 1. Incline Bench Press – work up to a 1‐rep max on the incline bench press. Try and avoid missed reps if possible. Once you achieve your max single for the day, then perform 3 sets of 5-8 reps at 75% of 1RM and 1 set of 8-12 reps at 60% of 1RM. Rest as needed between sets 2. Dips - 5 sets of max reps (aim for minimum of 25 total reps) Tuesday – Deadlift Intensity / Testing 1. Light Squat – 3 x 5 @ 60% of 1RM 2. Deadlifts – work up to a 1-rep max on the deadlift. Try and avoid missed reps if possible. Once you achieve your max single for the day perform 1 set of max reps at 75% of 1RM. You may use lifting straps for the back off set 3. One Arm DB Rows or Seated Rows 3-5 sets of 8-10. Rest 2-3 minutes between sets. Thursday – Overhead Press Volume 1. Overhead Press – after warm ups, perform 5 x 4 or 4 x 5 @ 80% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Close Grip Bench Press – after warm ups perform 3 sets of 5‐7 reps + 1 set of 10-12 reps 3. Triceps Extensions – 3‐5 sets of 10‐15 reps Friday – Squat Volume 1. Back Squat – after warm ups, perform 5 x 4 or 4 x 5 @ 80% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Stiff Leg Deadlift – 2-3 sets of 5 reps. 3. Chin Ups or Pull Ups – 3-5 sets of max reps or Pul downs 3-5 sets of 8-10 Week Three Monday – Overhead Press Intensity 1. Overhead Press – after warm ups, perform 3 x 3 or 4 x 2 @ 90% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Seated Dumbbell Press: 3‐5 sets of 8‐10 reps. Rest 2-3 minutes between sets, use a full range of motion. 3. Triceps Extensions: 3‐5 sets of 10-15 reps. Tuesday – Squat Intensity 1. Back Squat – after warm ups, perform 3 x 3 or 4 x 2 @ 90% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Rack Pull – perform a set of 5 reps with 5-20 lbs more than you used in week 1. Deload the bar by 10% and perform a set of 8-10 reps. 3. Barbell Rows 3-5 sets of 8-10. Rest 2-3 minutes between sets. Thursday – Overhead Press Volume 1. Overhead Press – after warm ups, perform 5 x 3 or 4 x 4 @ 85% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Close Grip Bench Press – after warm ups perform 3 sets of 4-6 reps + 1 set of 10-12 reps 3. Triceps Extensions – 3‐5 sets of 10-15 reps Friday – Squat Volume 1. Back Squat – after warm ups, perform 5 x 3 or 4 x 4 @ 85% of Monday’s 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Stiff Leg Deadlift – 2-3 sets of 4 reps. 3. Chin Ups or Pull Ups – 3-5 sets of max reps or Pulldowns 3‐5 sets of 8-10 Week Four Monday – Bench Intensity 1. Incline Bench Press – after warm ups, perform 3 sets of 2-3 reps with 90% of your week two 1RM. Then back off to 80% of 1RM and perform 1 set of max reps. Then back off to 65% and perform 1 set of max reps. (Example: 1RM = 275. 3x3x250, 1xMaxRepsx220, 1xMaxRepsx180) Rest as needed between sets 2. Dips - 5 sets of max reps (aim for minimum of 25 total reps) Tuesday – Deadlift Intensity 1. Light Squat – 3 x 5 @ 65% of 1RM 2. Deadlifts – after warm ups, perform one max set at 90% of your week 2 1RM (2-4 reps). Then, deload the bar to 80% of 1RM and perform a second max set of 5‐8 reps. Rest as needed between sets. 3. One Arm DB Rows or Seated Rows 3-5 sets of 8-10. Rest 2-3 minutes between sets. Thursday – Overhead Press Volume 1. Overhead Press – after warm ups, perform 5 x 6 @ 75% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume (5 sets, 6 reps) 2. Close Grip Bench Press – after warm ups perform 3 sets of 6-8 reps + 1 set of 10-12 reps. Try and beat what you previously did for 6-8 reps in week 1 by either adding weight or adding reps. 3. Triceps Extensions – 3-5 sets of 10-15 reps Friday – Squat Volume 1. Back Squat – after warm ups, perform 5 x 6 @ 75% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume. 2. Stiff Leg Deadlift – 2-3 sets of 6 reps. Try and beat what you did in week 1 for sets of 6. 3. Chin Ups or Pull Ups – 3‐5 sets of max reps or Pulldowns 3‐5 sets of 8‐10 Week Five Monday – Overhead Press Intensity 1. Overhead Press – after warm ups, perform 3 x 2 or 6 x 1 @ 95% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Seated Dumbbell Press: 3‐5 sets of 8-10 reps. Rest 2-3 minutes between sets, use a full range of motion. 3. Triceps Extensions: 3-5 sets of 10-15 reps. Tuesday – Squat Intensity 1. Back Squat – after warm ups, perform 3 x 2 or 6 x 1 @ 95% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume (3 sets of 2 or 6 sets of 1) 2. Rack Pull – perform a set of 5 reps with 5-20 lbs. more than you used in week 3. Deload the bar by 10% and perform a set of 8-10 reps. 3. Barbell Rows 3‐5 sets of 8-10. Rest 2‐3 minutes between sets. Thursday – Overhead Press Volume 1. Overhead Press – after warm ups, perform 5 x 5 or 6 x 4 @ 80% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Close Grip Bench Press – after warm ups perform 3 sets of 5-7 reps + 1 set of 10-12 reps. Try and beat what you did in week 2 for sets of 5-7 by either adding weight or adding reps. 3. Triceps Extensions – 3-5 sets of 10-15 reps Friday – Squat Volume 1. Back Squat – after warm ups, perform 5 x 5 or 6 x 4 @ 80% of Monday’s 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume 2. Stiff Leg Deadlift – 2-3 sets of 5 reps. Try and beat what you did in week 2 for sets of 5 reps. 3. Chin Ups or Pull Ups – 3-5 sets of max reps or Pulldowns 3-5 sets of 8-10 Week Six Monday – Bench Intensity 1. Incline Bench Press – after warm ups, perform 3 x 2 reps or 6 x 1 with 95% of your week two 1RM. Then back off to 85% of 1RM and perform 1 set of max reps. Then back off to 70% and perform 1 set of max reps. (Example: 1RM = 275. 3x2x260, 1xMaxRepsx235, 1xMaxRepsx190) Rest as needed between sets 2. Dips ‐ 5 sets of max reps (aim for minimum of 25 total reps) Tuesday – Deadlift Intensity 1. Light Squat – 3 x 5 @ 70% of 1RM 2. Deadlifts – after warm ups, perform one max set at 95% of your week 2 1RM (2-3 reps). Then, deload the bar to 85% of 1RM and perform a second max set of 3-6 reps. Rest as needed between sets. 3. One Arm DB Rows or Seated Rows 3‐5 sets of 8-10. Rest 2-3 minutes between sets. Thursday – Overhead Press Volume 1. Overhead Press – after warm ups, perform 5 x 4 or 6 x 3 @ 85% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume (5 sets of 4 or 6 sets of 3) 2. Close Grip Bench Press – after warm ups perform 3 sets of 3-5 reps + 1 set of 10-12 reps. 3. Triceps Extensions – 3-5 sets of 10‐15 reps Friday – Squat Volume 1. Back Squat – after warm ups, perform 5 x 4 or 6 x 3 @ 85% of your week 1 1RM. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume. 2. Stiff Leg Deadlift – 2-3 sets of 4 reps. Try and beat what you did in week 3 for sets of 4. 3. Chin Ups or Pull Ups – 3‐5 sets of max reps or Pulldowns 3‐5 sets of 8‐10 Week 7 (Deload + Strength Lifting Meet) Tuesday – Squat & Overhead Press Deload 1. Back Squat 3 x 3 @ 75% of 1RM 2. Overhead Press 3 x 3 @ 75% of 1RM Saturday -­­ MEET Recommended Meet Strategy: d. Attempt #1: Open with 90%-95% of your week one 1RM e. Attempt #2: Attempt a 5% increase from your week one 1RM (est. 10-20 lbs) f. Attempt #3: Attempt an increase from Attempt #2 based on feel (est. 5-20 lbs) Week 7 Deload (No Meet) Tuesday – Squat & Overhead Press Deload 1. Back Squat 3 x 3 @ 70% of 1RM 2. Overhead Press 3 x 3 @ 70% of 1RM Friday – Squat, Overhead Press, Deadlift Deload 1. Back Squat 3 x 3 @ 75% of 1RM 2. Overhead Press 3 x 3 @ 75% of 1RM 3. Deadlift 1 x 3 @ 75% of 1RM Post Meet Note If you want to restart the training cycle immediately following your strength lifting meet, then you can skip the testing days altogether in week 1. Take 3‐4 days of complete rest following your meet and resume training on Thursday and Friday with your volume workouts for Press & Squat at 75%. In Week 2 you can skip the Deadlift 1RM attempt on Tuesday and simply perform the volume work for 1 set of max reps @75% as prescribed. All % work in your immediate post meet training cycle will be based off your best lifts at the meet FAQs About the Program How do I determine what weights to use for the Dumbbell Pressing exercises? (flat and incline press, seated press, etc.) I prefer to do 1 light warm up set just to get the stretch at the bottom of the exercise and get a feel for the movement. Then I attempt my heaviest set that reaches failure or near failure in the 8-10 range. Following that movement I recommend you rest only 2-3 movements and perform descending sets where you will lower the weight slightly from set to set to keep reps in the 8-10 range. If your heaviest set achieves at least 10 reps then go up in weight the next time you do this movement. Using a sets across approach with DB exercises (same weight for every set) will generally result in you using a weight that is too light to maintain your rep range, or will lead to your last set falling way too short of your target rep range, or will require you to rest way too long between sets to achieve your desired rep range on all your sets. For Triceps Extensions – what exact exercise should I use? I recommend you rotate through a handful of different exercises each time you train triceps. Performing the same exercises at each workout will lead to stagnation and even inflammation in the elbow. Good choices are: lying triceps extensions with an ez-curl bar, lying triceps extension with dumbbells, overhead triceps extensions with an ez-curl bar, overhead triceps extensions (single arm) with a dumbbell, cable pressdowns, or any assortment of triceps machines available to you. Where should I set up the bar for Rack Pulls? I prefer just a few inches below the knee. I also recommend that you use a double overhand grip with a pair of lifting straps for this exercise. Generally you can Rack Pull 5-10% more than you can deadlift, but this varies from lifter to lifter. If this exercise is new to you, you may not Rack Pull much more than you Deadlift. Any tips for Stiff Leg Deadlifts? Begin with the bar on the ground like a regular deadlift. You will pull each rep from a dead stop just like a regular deadlift. Allow a very slight bend in your knees. These are NOT “straight” leg deadlifts. If you are fairly flexible you can stand on a 2‐4 inch platform for extended range of motion and extra work on the hamstrings. I prefer double overhand grip with straps on these as well. Weight will generally be 20-30% less than your regular deadlift but you may have to experiment to find the appropriate load, especially if you are new to this exercise. Where should my hands be for Close Grip Bench Press? I prefer that your index finger be on the line where the knurling of the barbell meets the smooth part of the barbell. It’s about 16 inches apart on most bars. Be sure and use a spotter for close grips or set the pins up in your rack for safety. Close grips can die out rather unexpectedly due to triceps fatigue. Do I have to do my light squats before I deadlift? No. You can perform your light squats after deadlifts if you prefer, however, if you are competing then it is a good idea to condition yourself to deadlifting after you squat. How should I perform the Barbell Rows? Whatever style is comfortable to you. Immediately after Rack Pulls it can save time to just strip a bunch of weight off the barbell and do your rows from the pins in the rack from the same height you rack pulled from. Use very strict form. Keep your low back locked into extension and pull the barbell into the lower part of your bel y. Practice pulling from your lats and not your arms. I recommend double overhand grip with straps for these. It will help take the forearms and biceps out of the movement and help you focus on pulling from the lats. I’m too fat or too weak to do Chin Ups or Dips… Use a lat pull down machine for a chin up sub. You can use a double overhand wide grip or a chin grip on the bar. If you don’t have a Lat Pull machine available then perform bodyweight rows on a pair of TRX straps, Blast Straps, or Rings. These can be ordered cheaply from Rogue, EliteFTS, etc. If you can’t do Dips you can do another triceps extension exercise for 3‐5 sets of 10‐15 reps or sets of push-ups to failure. How can I make this into a 3-day Program? Follow the order of the workouts exactly as I have written out here, but simply train on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday (or whatever days fit your schedule). It doesn’t change the program at all, it simply extends your “week” by a few extra days. This is a great option if you are over 40 or otherwise have a very demanding professional or personal life that doesn’t allow you to always get your required sleep or calories in consistently. You also have the option of starting the first few weeks at 4 days per week and then changing to a 3 day per week routine as fatigue starts to build up in weeks 4, 5, and 6. Can I customize the program? The program has been proven to work with a number of my trainees over the years. You don’t need to customize the meat and potatoes barbell lifts that begin each training session. After the first 1-2 main lifts each day you can modify or skip altogether some of the assistance work. But you don’t need to add anything to this program. Appropriate modifications will generally be the removal or reduction in volume of some of the bodybuilding style assistance work if you find recovery to be an issue. A Note on Volume Days…. You will see that the volume work follows a 3-week wave that goes from 75-80-85% of 1RM in weeks’ 1, 2, and 3 and then repeats those same percentages in week 4, 5, and 6. However in weeks 4-6 there is an increase in the amount of volume you are asked to do at each of the prescribed percentages. This is intentional so try not to mess with your percentages. In week 4 when the volume loads drop from 85% back down to 75% I want you to feel a perceived reduction in workload. If you want to add a small amount of weight to your volume days in weeks 4-‐‐6, this is permissible, but be smart…. take into account you are already doing more sets/reps than you did in weeks 1-3. If any of your volume days feel easy you can make the workout more difficult by decreasing your rest time between sets, or introducing pauses into the bottom of your squat or bench press. You can also focus on increasing your bar speed during your sets if the weights feel light. As the late great Bill Starr used to say…make the plates rattle at the top! The KSC Method for Power-Building Training Split A complete blueprint for building mass, increasing strength, and enhancing your physique. This is a complete plan and no detail is spared. Includes: How to set up the ideal 5-day per week training split for maximum intensity at every workout and complete recovery in between. Learn how to take advantage of the direct/indirect system for optimal muscle stimulation Periodized plan for all major barbell lifts. Keep your Squat, Bench Press, Deadlift, and Overhead Press progressing all year long with my 8-5-2 three-week training cycle. Discover why this is the perfect rotation of rep ranges for year round gains in mass, strength, and power An easy to follow training template for each day of the week. All muscle groups are worked in complete balance throughout the course of the week. You will have no weak links! Learn how to correctly implement the conjugate system with your primary lifts and your assistance template. How to optimize various training techniques such as rest-pause, drop sets, descending sets, and density sets for optimal muscle growth all year long. Introduction 10 Power-Building Principles You Should Follow to Increase Strength, Build Muscle Mass, and Refine Your Physique What is Power-Building? Power-building is certainly not a new term, nor is it a new philosophy, and I certainly didn’t invent the concept. As the name implies Power-building is simply the integration of two important disciplines in the strength sports – power lifting and body building. Within each sport, there are power-builders that have learned to incorporate the best tactics and strategies from each discipline to get the best of both worlds – more muscle & more strength. Obviously, power lifting is centrally focused around the consistent improvement of a lifter’s absolute strength in the Squat, Bench Press, and Deadlift – 3 cornerstone lifts for anyone serious about strength and size. Elite powerlifters are among the strongest people on the planet and even without a lot of “fluff” work, many of them have physiques that are reflective of years of work underneath a heavy barbell. Bodybuilders on the other hand are not judged on their ability to perform a lift, but rather on the amount of muscle mass they carry, the development of individual muscle groups, and balance and symmetry across the entire physique. Integration of the two disciplines is Power-Building. In my experience, a successful blend of both powerlifting and bodybuilding principles is the key to building more muscular bodies that don’t just look strong, but in fact - are strong. The reality is that most guys (and many gals) want both – more strength and more muscle. The pursuit of just one or the other will indeed yield gains in both areas, but not nearly as quickly or dramatically as when both are pursued simultaneously. The key is striking the right balance in the amount of energy you invest into each area. There are in fact, many strong power lifters who don’t look the part. And on the flip side, there are some genetically gifted bodybuilders and physique athletes who quite simply aren’t that strong. In my opinion, athletes in BOTH categories would improve in their constituent sports if they borrowed a little bit from each other. And why wouldn’t you want both? Strength is foundational to a better life. There is no instance in life or sport where stronger isn’t better. But who wants to put in all that time under the barbell and not have anything to show for it? There is nothing wrong with wanting to look like you lift. A better physique breeds higher levels of confidence in both your professional and personal life. Is Power-Building for Me? But what if I only care about strength? You are saying, “Seriously Andy, I left my vanity and ego back in college, I’m not looking to become a bodybuilder. I just want to get stronger and live a healthier life-style.” Cool. My programs are not competitive bodybuilding programs. Competitive Bodybuilding is a highly specialized sport with much much more involved than simply building muscle mass. Quite frankly, while I admire the dedication and discipline of the athletes– I think the whole sport is a little weird. Something about getting all oiled up and flexing at a bunch of other dudes that disturbs me. BUT, there is something to learn from the training regimen of a smart high level natural bodybuilder. These guys are the best in the world at adding muscle mass while keeping body fat low. Why not borrow a little insight from them to help you look your best? The reality is that at some point just training the Squat, Bench, and Deadlift isn’t going to work anymore. There are a myriad of ways to manipulate volume and intensity in an effort to just focus on and progress the basic lifts. For many, this will work for the first year (and maybe even two years) of training, but at a certain point you have to go outside the box a little and start addressing weak points in the system and work on the development of lagging muscle groups. This is where bodybuilding style training comes in handy. With added assistance and supplemental work to the basic barbell exercises, we are looking at strengthening all the potential weak links in the chain. And also, by getting bigger you will be improving leverages all throughout the body that will help you lift more weight. I will always argue that the basic barbell lifts should form the core of any strength training or muscle building plan. But for the majority, a “basics only” approach will not last forever. I’ve done consultations with hundreds of strength athletes over the years who had been “stuck” on the same numbers for months or even years without improvement. No matter what variation of Squat/Bench/Dead/Press they try – they wind up back at the same old spot. We can fix that. But what if I only care about physique and aesthetics? You say, “Strength is cool, but my priorities are looking awesome with my shirt off at the pool. I’m not really excited to try and lift a bunch of really heavy weight.” First, a natural lifter isn’t going to get big and muscular without lifting heavy and getting strong first. Except for the few genetically elite among us, you are going to have to spend some time straining against some heavy squats and deadlifts to build a real physique. Unless you are Herschel Walker or Bo Jackson, you aren’t going to build a muscular physique by doing pushups and sit ups every night. And if you have those kind of genetics you aren’t reading this anyway. Second, I’m a strength coach by trade. Teaching people to get strong is what I do for a living. If you aren’t interested in strength……well, try P90X. I hear it’s great. 10 Key Principles for Successful Power-Building 1. You Must Train Heavy: For optimal size and strength you must train with heavy weights often. For the purposes of power-building that means that every workout, or nearly every workout should begin with an exercise trained maximally between 1 and 8 reps. The 1-8 rep range covers the entire “strength spectrum” of rep-work. Anything more than 8 is getting into pure endurance and hypertrophy work which will come later in the workouts. But first each day, while you are fresh, you need to be straining against weight that causes failure or near failure within that rep range. In my own programming for my clients, I typically use a lot of sets of 8, sets of 5, and sets of 2. Occasionally lifters will fail to get their prescribed reps or will exceed their prescribed reps and so over time we get sets of 1, 3, 4, 6, and 7 as well. Over the course of several months we get maximal work at just about every number within the strength spectrum. Programming like this covers all your bases and prevents stagnation by varying the loads on a weekly basis while still training “heavy” with a productive combination of sets and reps. Every workout should start with a barbell exercise. Even going “heavy” on dumbbells and machines doesn’t create the same stress that barbells do. The core of my power-building programs are Squats, Deadlifts, Bench Press, and Overhead Presses. I will also use variants of those exercises for the first lift of the day when things get stagnant. More on that later. Heavy, low rep work is effective but must be used with caution and respect. Heavy loads can not only beat up the joints and connective tissue if overused, but they fatigue the nervous system. Especially on sets that are 4 reps or below, the central nervous system is highly stressed. Too much of this, too often can produce overtraining and regression. I only use very heavy low rep work on the first exercise each day and each lift is only trained this heavy once per week. 2. You Must Do Higher-Rep Work: If we are going to consider sets of 1-8 reps “low rep” work, then high rep work is really anything above 8 reps. How high can vary depending on the lift and the muscle group being trained. Higher reps are a means of accumulating a lot of volume (which leads to more growth) and producing a “swelling” effect in a muscle group often referred to as Sarcoplasmic Hypertrophy. This is essentially the ability of the muscle cells to pull in more water and more glycogen and this leads to muscles that are larger in size. Some research also shows that an acute increase in blood flow to a muscle (such as during multiple high rep sets) creates a hormonal response that is favorable to growth and faster tissue repair. While not directly responsible for increases in strength, a larger muscle produces better leverage around a joint than does a smaller muscle. In other words – big quads squat more weight than small quads. And big pecs and triceps bench press more weight than small pecs and small triceps. Seems rather intuitive doesn’t it? For most barbell and dumbbell exercises I like the traditional bodybuilding rep range of between 8-12 reps for hypertrophy. Following the heavier low rep work I find that 2-3 sets of 8-12 reps to be sufficient on most exercises provided failure or near failure is occurring on each set. Depending on the exercise and the muscle group being trained, I will also take trainees much higher in reps than 8-12. Often we go into the 15-20 rep range and some days as high as 50 reps. I should be very clear that rep ranges this high are generally performed for just ONE all out set. Furthermore, these sets are usually achieved through traditional bodybuilding techniques such as Rest-Pause sets and Drop Sets. Using either Rest-Pause or Drop Setting, trainees will break up a set of, say 50 reps, in multiple lower rep sets with very brief rest in between. So if we finish off a chest workout with a set of 50 push-ups, the trainee is likely not going to achieve all 50 reps in a single effort if we’ve hit the preceding exercises with vigor. Instead, he might get 28 reps, 13 reps, and 9 reps with a 15-20 second rest between efforts. This creates “training density” (aka – a lot of work done in a short period of time) and is extremely useful when trying to build muscle mass. High rep training, especially if techniques like drop sets or rest-pause sets are used, must be used with the appropriate exercises to be effective. Typically these are done at the end of a training session with bodyweight, machines, or cables – all of which are inherently less stressful than barbells. The goal is not to get so sore that we can’t walk for 2-weeks. High rep work is meant to support and compliment the heavier foundational barbell exercises that form the core of the power-building program. If you are creating so much soreness and inflammation with your high rep-work that you can’t progress or even train your heavier lifts, then you are missing out on the bigger picture and costing yourself progress. Used by itself as a singular training protocol, high-rep work is not the most efficient means of building strength or muscle. Only when combined with heavy low-rep barbell work does it become a very powerful catalyst for continual growth and development of a better physique. 3. Training 5 times Per Week is Optimal The power building programs I prescribe really cannot be done with less than 5 training sessions per week if you really want to train optimally for both strength and physique. Each lift and each muscle group requires a specific amount of high intensity strength work, and volume-based accessory work that would be nearly impossible to fit into a 2-3 day per week schedule. 4 days could probably work if you want to ignore some of the smaller muscle groups. It’s your call on that. Keep in mind that each training session is really only based around ONE main heavy barbell lift and usually only 1 or 2 muscle groups. So we aren’t looking at training the whole body at each session or even half the body. Each workout should be able to be accomplished in an hour or less if you are staying focused during training. For a natural trainee especially, excessively long drawn out workouts are difficult to recover from. I believe that shorter more frequent training sessions are superior. The ideal 5-day split for this program is 2-on-1-off, 3-on-1-off. This puts you in the gym 5 days per week while taking Wednesday and Sunday off from training. For those who want to stay out of the gym completely on the weekends, the KSC Method for Power-Building can be trained on a 5 on, 2 off training split. 4. Train Each Muscle Group Directly & Indirectly Each Week I am an advocate for each muscle group to be trained every 48-96 hours for optimal growth and strength development. But, I do not believe that each muscle group should be annihilated every 48-96 hours. Too frequent high intensity and/or high volume training will lead to overtraining, stagnation, regression, and eventually injury. Instead I think the better approach is to hit each muscle group hard once per week with both high intensity exercises and high volume exercises. At another point during the week, the muscle group should be touched on “indirectly” to speed up recovery, prevent detraining, and spur growth. For instance, in the KSC Method for Power-Building, you will hit shoulders and triceps hard, during one training session, but then 72-96 hours later, those muscles will be hit again, indirectly, when you do your chest training. And the chest is hit indirectly during your tricep session if you choose to hit some close grip bench presses for example. In the KSC Method for Power-Building, the training week has been carefully organized so that all muscle groups are trained in this direct/indirect fashion. 5. You Can Squat Two times Per Week This may seem counter to the advice I just gave about training directly and indirectly each week – and in a way it is. The Squat is a unique animal, in that it can tolerate and responds well to more frequency.During the 5-day power-building program, two of those training sessions are lower body days. While each day thoroughly trains the lower body, one day is more quad dominant, and one day is more focused on the posterior chain (hamstrings, glutes, and spinal erectors). I of course understand that movements like the Squat and Deadlift are going to train both areas and it is silly to try and separate quads from hamstrings, so because the Squat so thoroughly trains both quads and hamstrings, I use the exercise on each of the two lower body days. Now, often times we use variations of the Squat and we oscillate between using the squat as the first exercise of the day for heavy sets, and using it as the second exercise of the day for more reps. For instance, one of my favorite combinations is to deadlift heavy first in the workout, followed by a low-bar box squat sitting way back onto the box as the second exercise of the day. This torches the posterior chain, but obviously trains the quads as well. Later in the week, we might start the second leg workout off with heavy Squats for low reps, and then do some higher rep work on exercises specifically for the quads. 6. You Should Train the Back Two Times Per Week As I mentioned before, in the KSC Method for Power-Building, one of the two weekly lower body sessions is primarily focused on exercises for the posterior chain. Almost always, we begin this workout with a heavy Deadlift or a variation of the Deadlift such as Stiff Leg Deadlifts or Rack Pulls. Obviously Deadlifts train the legs, but they also heavily train the erectors, lats, and traps. Deadlifts are technically our “indirect” day for the Back, but often times the soreness you feel the day after deadlifts feels a little more direct! Later in the week, we have another session just for the upper back and lats. This is a back hypertrophy day that focuses on exercises like chin ups, pull ups, lat pulldowns, an assortment of row variations, and also specific work for the traps and rear delts. Breaking up the back training into Deadlifts + Rowing/Pulling allows you to train each lift with the ideal amount of intensity. The result is a bigger, stronger back. 7. Prioritize Both Flat & Incline Bench Presses As a rank novice, any strength athlete should probably focus just on bringing up his traditional flat bench press. The flat bench press allows the use of the heaviest weights possible, and as a novice, this is most important for long term success. But later on as you move into a power-building routine, then the incline bench press becomes a critically important lift. First, getting strong on the incline will help drive up both your bench press and your overhead press. This is an assistance lift which gives you a 2-for-1 benefit, which makes it a winner. Second, for physique and aesthetic purposes, the incline press helps to fully develop the pectoral muscles. Full development of the upper pecs will make you look bigger and wider across the shoulder girdle. Most competitive bodybuilders will transition to incline presses as their primary chest movement at some point in their careers. In the KSC Method for Power-Building, we rotate back and forth between flat bench presses and incline bench presses as the first movement of the day. And we always do exercise number one with a barbell so that we are handling maximum poundages. Whichever movement does not come first, usually comes second. So if we start with the incline bench, we do flat benches second. And vice versa. Sometimes that second lift of the day is with a barbell, sometimes with a dumbbells. We rotate often to keep things fresh. 8. Use the Conjugate Method We have already alluded to this several times, we just haven’t called it by name yet. The conjugate method is something we have borrowed and adapted from strength coach Louie Simmons of the Westside Barbell Club. The athletes that Louie coaches at Westside are all advanced strength trainees who handle maximal poundages week in and week out all year long. Louie, like others, have found that most athletes cannot train maximally using the same series of lifts week in and week out. Even if rep ranges are tweaked each week, there is a certain level of physical and mental burnout that almost always sets in without at least a little variation in exercise selection. That conjugate method that Louie implements is one in which the main exercises each week are rotated in and out of the program on a near weekly basis. In other words, you never do the same thing two weeks in a row. The amount of lift variants one can come up with are nearly infinite. Just for squats for example, varying box heights, different types of specialty bars, and the use bands and chains provides the lifter with a staggering number of squat variants to train each week. For a novice or early intermediate trainee, this is both unnecessary and confusing. As a novice or early intermediate, you likely don’t need tons of variety on your lifts. The longer you train though, the more the conjugate method becomes useful to you as a means of keeping progression from stagnating. In the KSC Method for Power-Building, we have a built in mechanism for using the conjugate method (or rotating in different variations of the main lifts) without creating confusion or doing unproductive exercises. Most lifters do well on just a handful of variants to work with. For the Deadlift we might use regular Deadlifts, Rack Pulls, Deficit Deadlifts, and Stiff-leg Deadlifts. For the Bench Press we might use regular Bench Presses, Incline Bench Presses, Rack Presses, and Cambered Bar Bench Presses as part of a simple rotation. Over time you will discover what exercise variants drive up your main lifts and which do not. We also implement the conjugate method with our assistance work, actually more often even than the main strength work. It is important to rotate different assistance lifts in and out of the program with some regularity. How much or how little variation one uses is up to the individual lifter and the results he is getting from his programming. It also depends some on personality. Some lifters are creatures of habit that like routine and don’t like a lot of variety. Others get bored easily and if not given a system for implementing a little variety will often wind up in the weeds doing silly things out of sheer boredom. 9. Don’t forget the small muscle groups The vast majority of the gains you will experience on this program come from the primary barbell exercises that train the largest muscle groups. Squats and Deadlifts for the quads and hamstrings, Bench and Incline for the chest, and Chins and Rows for the lats. But remember this program is half bodybuilding. And a big part of the bodybuilding game is not just getting big, but developing a complete and well balanced physique. There is an old saying in bodybuilding that just because you are big doesn’t mean you are going to look big on stage. The development of all the little muscle groups are an important component of this. Areas of the body such as the side delts, traps, triceps, biceps, abs, and even calves go a long way toward giving you an imposing muscular physique. In the KSC Method for Power-Building, we don’t have any training sessions dedicated to just the small muscle groups. This is an inefficient use of time, as we want the majority of our time and energy spent on the big boy lifts. But once the big lifts are done you will have a training template to follow that allows you to dedicate the appropriate amount of time, energy, and effort into the development of all areas of your physique. 10. Cardio and Diet For Fat-Free Mass Contrary to the opinions of some, the best way to gain muscle mass is not to just sit around on your ass all day and eat ice cream and pizza. Yes, you absolutely have to eat a surplus of calories and protein if you want to gain muscular body weight. Not exactly breaking news. And no, you shouldn’t be jogging 5 miles per day if you want to get into power-building. The best mass gaining diet is one that puts you in a caloric surplus using high quality healthy foods. The “official” KSC Meal Plan uses 4-5 meals per day with specific types of foods at each meal. Then each lifter must adjust the amount of food at each meal to fit his goals as it pertains to the speed in which he or she wants to gain or lose weight. I have found that the simplicity of this plan makes it very easy for my clients to adhere to. The KSC Meal Plan is therefore only a very loose template in which almost everything is adjustable. Some may even need to add a meal or two to better meet their caloric and protein goals. Eating in a caloric surplus works well when a little bit of cardio is added into the overall training plan. This helps the body to better metabolize the excess calories for productive purposes. For a power-builder, cardio does not need to be excessive. An easy way to implement cardio is to add about 15-20 minutes of high intensity cardio work immediately following your training sessions each day. This doesn’t have to be done at every training session, maybe 2 or 3 of the 5 sessions each week. Most find that energy levels dictate that cardio be performed after the upper body sessions and is not necessary after the two weekly leg training sessions, which are obviously more demanding. Most any type of cardio work is fine other than long distance running. Power walking either outside or on an inclined treadmill, riding on a stationary bike, ellipticals, rowers, or pushing or pulling a sled are all acceptable forms of cardio. The key is to keep sessions short and intense. No need for 45-60 minute cardio sessions if your diet is in check. A little cardio each week not only helps your metabolism but it helps with overall recovery and it keeps you “in shape to train.” Many athletes and coaches forget that a certain level of fitness is required to perform demanding workouts in the weight room. Being in shape will help your between set recovery so that you can complete workouts in a timely manner, and still have the energy to go on about your day. The Program As we alluded to in the introduction, the best means of organizing a power-building training split is across 5 training sessions per week. 5 days per week of weight training enables the trainee to get in all the exercises each week without turning each individual workout into a marathon of a training session. If possible, we’d like to be in and out of the gym in an hour or so. Maybe 75-90 minutes if we include a little post workout cardio. If you try and condense all of the exercises in this program into a 2-3 day week sessions are going to be too long for most people’s schedules or recuperative abilities. The optimal 5-day training week is performed 2 days on, 1 day off. Then 3 days on, 1 day off. So a typical week might looks like this: Monday – Train Tuesday – Train Wednesday – Off Thursday – Train Friday – Train Saturday – Train Sunday – Off Obviously, you can adjust the training and rest days each week to fit your schedule, but if possible try and stick to the 2 on 1 off, 3 on 1 off protocol – it is designed this way for a reason. The training days and the rest days are placed where they are in order to create the optimal “spread” between exercises that will allow us to follow the “direct/indirect” training protocol. Below is how the actual training sessions fit into the split: Monday – Chest, Biceps Tuesday – Legs (Hamstring/posterior chain emphasis), Calves, Abs Wednesday – Off Thursday – Shoulders, Triceps Friday – Upper Back (lats, traps, rear delts, etc) Saturday – Legs (Quad emphasis), Calves, Abs Sunday - Off Notice that the two off days each week come after the heavy lower body days. This is by design. Squats and Deadlifts take a lot out of the central nervous system. If possible, it’s good to have a rest day after each time you do these heavy lifts. Even though squats don’t technically affect the upper body muscle groups, trying to lift the day after heavy squats or deadlifts generally results in just a general feeling of lethargy and overall weakness and a lack of explosion. This is CNS fatigue and it will kill a training session. Best to recover after you squat and pull heavy. Now, pay attention to how these training days are spread out through the week to achieve the direct/indirect training affect. There are 2 days and 3 days respectively between each lower body training session. There are also 2-3 days off between your deadlift session (Tuesday) and your upper back session on Friday. Remember that deadlifts are your “indirect” training day for your upper back. Biceps are trained indirectly on Friday during the upper back session, and then trained directly on Monday after chest training. Biceps are warmed up after a chest workout, but not fatigued. You should be able to train them fresh after chest. Chest is trained directly on Monday and then usually hit again indirectly on Thursday during the tricep workout. I often like to have trainees hit a close grip bench or do dips on their shoulder/tricep day so this satisfies our indirect movement. Shoulders and triceps are trained directly on Thursday, and then indirectly during our heavy bench and inclines on Monday. Abs and calves are trained directly 2 times per week but with a low volume of exercises. One exercise 2 times per week works well for both muscle groups. As you can see, the organization of this training split took some time to develop. It is suggested that you do not switch training days around if at all possible. If you cannot train on weekends then you can perform this on a Monday – Friday split where you simply eliminate the rest day on Wednesday and rest on both Saturday and Sunday. When used on occasion this split is not a problem, but the majority of the time, the mid-week rest day is preferred. The Training Days: Individual Workout Template Just for the sake of uniformity and consistency, on each of the 5 training days you will perform 5 exercises. On occasion you might decide to drop an exercise or even add an exercise, but this will give you a basic framework from which to operate off of. If a program has no structure it tends not to work as well. Trainees will start to “drift” in their programming and either add too much work, or do too little. A pre-set uniform training template works best for most in the long run. The structure of each training day will give you a template to plug your favorite exercises into. It will give you enough work to produce the strength and mass gains we want, but will limit you from adding in too much excess that eats into your recovery. In general, we will do 3 exercises for the large muscle groups, and 2 exercises for the small muscle groups. Below is just the basic template we will follow. Sets, reps, and specific exercise selection advice is to follow. Monday - Chest & Biceps 1. Barbell Bench Press (Flat or Incline) 2. Barbell or Dumbbell Bench Press (Flat or Incline) 3. Dips or Flys 4. Barbell or Dumbbell Curl 5. Barbell, Dumbbell, or Cable Curl Tuesday – Legs, Calves, Abs 1. Deadlift or Deadlift Variant or Low Bar Box Squat 2. Deadlift, Deadlift Variant, Low Bar Box Squat, or Goodmorning 3. Light Hamstring: – leg curl, glute ham raise, reverse hyper, back extensions, etc. 4. Seated Calf Raise 5. Hanging or Lying Leg Raises (abs) Thursday – Shoulders, Triceps 1. Standing Barbell Press 2. Seated DB Press or Seated Machine Press 3. DB Lateral Raises (side delts) 4. Close Grip Bench, Dips, or Tricep Extensions (bar, dumbbell, machine, cable, etc) 5. Tricep Extensions (bar, dumbbell, machine, cable, etc) Friday – Upper Back 1. Chin Ups or Pull Ups 2. Pulldown Variation 3. Row Variation (barbell, dumbbell, t-bar, cable, machine, etc) 4. Rear Delts or Row Variation 5. Traps (shrug variation) Saturday – Legs, Abs, Calves 1. Squats 2. Hack Squat, Leg Press, or Front Squat 3. Leg Extensions 4. Standing Calf Raise 5. Decline Sit Ups A few notes about using this template that might be helpful……… Chest & Bicep Day: Always start with a barbell exercise, flat or incline Use the inverse angle, flat or incline, second and perform with either DBs or a barbells Finish chest training with either dips (if you are strong enough to do them as a 3 rd chest movement) or a Cable fly. Go fairly heavy with either DBs or BBs to start the bicep workout Use the inverse, DB or BB, or a cable machine to finish the biceps with higher reps Lower Body (Hamstrings). The 3rd hamstring movement is always lighter and easier than the first 2. Avoid doing 3 movements for hamstrings that all hit the lower back really hard. The vast majority of the time, lying leg curls make the best movement to finish this workout. Shoulders & Triceps Seated DB Presses and Machine Presses should be performed with elbows flared out and the hands/forearms in line with the ears. This will develop the side delts. Upper Back Starting with Chins or Pull Ups is recommended. To help get these stronger, do a pulldown variation second. After Chins, use a wide grip pulldown that mimics a pull up. After Pull Ups, use a chin grip pulldown or v-grip pulldown. The best rear delt exercise is a seated row machine with handles designed for the rear delts. These will be horizontal handles and the machine should allow you to pull the handles high, with hands in line with the shoulders. Shrugs are not heavy power shrugs. These are strict shrugs designed to produce the pump. Heavy deadlifts will give your traps the heavy weight stimulus they need. Legs (Quads) Front Squats performed on a smith machine are excellent for the quads after heavy back squats. These will save your back and allow you to focus just on your quads. 90% of quad workouts are finished with leg extensions. There is nothing better for training purely for the pump in your quads. Programming Within The Template (8-5-2 protocol) So now we basically know what each training day will look like in terms of overall structure – but the devil is always in the details. As you can see on many of the training days there is a high degree of variability as to how you might organize a workout. We’ll discuss this shortly. But first, we need to understand and explain the set and rep protocol that will be used with each exercise. The most critical ingredient in any training program is the exercise selection, and next is the formula for progression. That is – how are we going to go about ensuring long term progression on all the major lifts? Let’s face it – if you are squatting 135x8 right now, you need to be squatting 315x8, or 405x8 if you want to be a power-builder. But you need a plan to get you there. Enter the 8-5-2 protocol. The 8-5-2 protocol is based around a 3-week rotation between each of the three rep ranges. You will perform each rep range for 3 sets across. That means 3 sets with the same weight used on each set for the prescribed number of reps each week. Here is what it looks like: Week 1: 3 x 8 Week 2: 3 x 5 Week 3: 3 x 2 After the 3rd week, you will start the rotation over again, but you will use a little more weight than the previous cycle. For upper body lifts this will be 2-5 lbs, for lower body lifts this will be 5-10 lbs. A sample 9 week rotation (or 3 times through the cycle) would look like this: Week 1: 3 x 8 x 300 Week 2: 3 x 5 x 330 Week 3: 3 x 2 x 360 Week 4: 3 x 8 x 305 Week 5: 3 x 5 x 335 Week 6: 3 x 2 x 365 Week 7: 3 x 8 x 310 Week 8: 3 x 5 x 340 Week 9: 3 x 2 x 370 Note that there is no mention of the concept of a “training max.” This is common in other similar programs such as Jim Wendler’s 531 program. We don’t use training maxes on this program, we simply add 2-10 lbs from the weight we used in the previous cycle. How to get your starting weights for the program? If you are coming from the Starting Strength Program or one of the programs from Practical Programming for Strength Training then you should have a decent gauge on what you can do for 3 x 5. Use that as a starting point. Using that known factor (3x5) – take 10% off that number to establish your starting weights for your 3x8 week. Then add 10% to your 3x5 weight to establish starting weight for your 3x2 week. So if you know you can do 3x5x250 then you would estimate your 3x8 week to start at 225 and your 3x2 week to start at 275. If you want to use percentages based off of a 1RM (1-rep max) then you could probably start this program like this: 3 x 8 x 70% of 1RM 3 x 5 x 80% of 1RM 3 x 2 x 90% of 1RM After those initial 3 weeks then percentages become irrelevant. You simply add 2-10 lbs each cycle to whatever you did in the previous cycle. What if I don’t get all my sets and reps on a given week? This is going to happen. You are going to have workouts where you miss your goal and fall short of your set/rep targets. But there is a plan in place to deal with this. If you miss a target set/rep goal then the next time through the cycle you will repeat that same weight again. But you will continue to move up on the other two rep ranges if possible. Look at the following example very carefully: Week 1: 3 x 8 x 300 Week 2: 3 x 5 x 330 Week 3: 3 x 2 x 360 Week 4: 3 x 8,7,7 x 305 (Lifter did not achieve all 3 sets of 8) Week 5: 3 x 5 x 335 (lifter progresses his 3x5 range despite misses last week) Week 6: 3 x 2 x 365 Week 7: 3 x 8 x 305 (Lifter repeats weight from week 4 and achieves all reps) Week 8: 3 x 5 x 340 Week 9: 3 x 2 x 370 Week 10: 3 x 8 x 310 (lifter moves up in weight for 3x8 week) The key with the 8-5-2 progression is that each rep range positively influences the other two. So if you are missing weights on one rep range, keep progressing on the other rep ranges. This is what will get you un-stuck. The beauty of the 8-5-2 progression is that it works the entire spectrum of strength training rep ranges over a 3 week period. The sets of 5 reps are the tried and true basis of any strength program. They are the metabolic middle that drive everything. But you can’t do just 5s every week forever. You’ll burn out and stagnate. Sets of 8 reps create some profound muscular endurance and work capacity that make 5 rep sets easier. Sets of 8 across also build some tremendous mass when used on the basic barbell lifts. Sets of 2 (or “doubles”) give us some much needed work in that neural range that trains our nervous system to strain against heavy loads. But doubles don’t burn out our CNS like heavy singles across are known to do. So we use doubles as part of our year round rotation. It is very important to understand that the 8-5-2 progression uses a “sets across” approach for programming. i.e. the same weight for all 3 work sets at a given rep range. This is very hard to do but very effective for long term programming for size and strength. A critical element to the sets across approach is rest between sets. It needs to be long. In all likelihood we are looking at 5-8 minute rests between work sets. Less than that and you are going to see too many missed reps on your second and third sets and you’ll never move your weights forward. (*For deadlifts it is recommended that straps be used on the second and third set each week. If the lifter cannot perform or recover from sets across on the deadlift then sets 2 and 3 can be done as back off sets at a 5-10% reduction from the 1st work set of the day). No rep range is used more than once every 3rd week. This keeps things fresh – mentally and physically. The same exercises for the same rep range week in and week out will not work forever. There has to be some sort of undulating stress from week to week or stagnation is the inevitable consequence. However, training in “blocks” doesn’t work either. For instance – 4 weeks of 8-rep sets, 4 weeks of 5-rep sets, and 4 weeks of 2-rep sets used to be common in lifting and athletics. The problem is that you spend 8 weeks or more out of each rep range. You lose the effects of each rep range after that length of time. How to apply the 8-5-2 progression The 8-5-2 progression will not be used with every lift in the program. It will only be used with the primary lift at the beginning of each workout. Bench Presses, Deadlifts, Overhead Presses, and Squats are the only lifts that will follow this protocol. The 8-5-2 progression can also be applied to exercise variants that are being used in lieu of the traditional lifts for any 3-week cycle. So a lifter might choose to switch from flat to incline bench presses to start his chest workout. The 8-5-2 progression would then be applied to the incline bench press. A lifter might decide to Rack Pull or Deficit Deadlift in lieu of standard deadlifts to start his hamstring workout. The 8-5-2 protocol could be applied there as well. A Note on Subbing for the Primary Lifts This is as good a place as any to briefly discuss how one should go about substituting different exercises for the main lift of each training day. As we noted in the introduction, Louie Simmons and the Westside Barbell method are famous for use of the conjugate method which is a system of training that basically swaps out the main exercises on a weekly basis, using as many variations as possible for each lift. We aren’t going to do that on this program. For starters at least – we would be swapping out the main exercise every 3 weeks. Or basically enough time to get through an entire 3-week cycle. But it could be longer. Perhaps several 3 week cycles are used before another switch is made. An example might looks like this: Week 1: Bench Press 3 x 8 Week 2: Bench Press 3 x 5 Week 3: Bench Press 3 x 2 Week 4: Incline Press 3 x 8 Week 5: Incline Press 3 x 5 Week 6: Incline Press 3 x 2 Week 7: Bench Press 3 x 8…… Deadlifts often benefit from some variation as well. Heavy Deads are just really hard to recover from. When used too often for too long, they tend to go stale or even regress. Like the Bench, it can be subbed out with some basic deadlift variations such as the Rack Pull (a partial deadlift pulled from knee to mid-shin height) or a Deficit Deadlift (deadlifts pulled while standing on a 2-3 inch elevated platform). After the lifter has many months of experience under his belt he may assign certain exercise variants to certain rep ranges in order to set up a 3-week cycle that rotates exercises as well as rep ranges every week. For the Deadlift it might looks like this: Week 1: Stiff Leg Deadlift 3 x 8 Week 2: Deadlifts 3 x 5 Week 3: Rack Pulls 3 x 2 Or for the Bench Press it might look like this: Week 1: Incline Bench Press 3 x 8 Week 2: Bench Press 3 x 5 Week 3: Rack Bench Press 3 x 2 Remember, these rotations are just purely for example – they are hypothetical and not prescriptive. The purpose of this discussion is to give the lifter some options for future training in the months and years to come so that this program can yield long term dividends and progression. Switching out the primary exercise is going to be most common on Bench day and Deadlift day. The Press and the Squat do not benefit nearly as much from being rotated with other exercises. Simply running them through the 8-5-2 rotation should be enough variability to keep progress going on those two lifts. If the discussion about swapping out exercises and different variations is confusing to you, then don’t worry about it. Stick with the tried and true big 4 and just use the 8-5-2 protocol. Programming the other lifts & exercises As we mentioned – the only lifts that use the 8-5-2 protocol are the first lift of each training day – The Bench Press, Deadlift, Press, and Squat and perhaps their variants. Exercises 2-5 each day will use a slightly less strict and more fluid form of programming and the pace will quicken significantly. In general, we will use one of two approaches for all other lifts in the program. First is just standard bodybuilding rep range sets to failure and the use of descending sets. Depending on the exact exercise in question we’ll generally do 3 sets of 8-12 reps to positive muscular failure. Slightly less than full rest times are taken between sets, but weight is lowered around 10% each set. In general we are looking at 1-3 minutes between sets and maximum effort is given to each set. The amount of rest between sets is largely depending on the exercise. Side Delt raises might be as little as 45 seconds to a minute, while Hack Squats might be around 3 minutes between sets even when weight is lowered each set. Let’s look at how this might be applied to exercises for several different workouts. Chest: Bench Press 3 x 8 (sets across, full rests) Incline Bench Press o 225 x 8 o 205 x 8-10 o 185 x 10-12 In this example the lifter did his first work set “all out” with 225 lbs. After a brief 2-3 minute rest, approximately 10% is stripped off the bar to 205 and another set is done to failure. After another brief rest, another 10% is stripped off the bar and another maximum set is performed. Quads: Squats 3 x 5 (sets across, full rests) Hack Squat Machine o 3 plates per side x 10 o 2 ½ plates per side x 10 o 2 plates per side x 10 (for many machines, % of weight is not a necessary calculation. For logistical ease, simple plate arrangements on the machine will suffice). Shoulders: Press 3 x 2 (sets across, full rests) Seated DB Press o 75’s x 8 o 70’s x 8 o 65’s x 10 Hamstrings: Deadlifts 3 x 5 (sets across, full rests) Stiff Leg Deadlifts (on 4 inch platform) o 315 x 8 o 275 x 10 o 225 x 12 (in this example, larger than 10% offsets are used between sets. This is appropriate when “big” exercises are used that are highly stressful. In this example, simple/standard plate arrangements are used to make unloading more efficient). For most exercises, when this approach is utilized the goal is reach positive failure between 8-12 reps. However this isn’t terribly rigid. On occasion the first set (the heaviest) might not achieve 8. Likewise, the last set will occasionally exceed 12 and get to 15 or more reps. No big deal. But remember, the goal for this exercise is around 8-12 reps on most sets. If you are consistently falling well short of 8 reps on your first set (or especially if you are falling below 8 reps on sets 2 and 3) then you are using weights that are too heavy or your percentage offset between sets is not large enough. Some experimentation is in order for each exercise. For progression, use the first set of the day as your primary metric. Once you achieve 8 reps with a given weight you can bump it up and set your descending sets off of that first set. The second protocol we use is what I call density sets. These sets occur when an exercise is given a target number of reps to achieve in a short amount of time. This is generally not less than 20 reps, but could be as much as 100 reps depending on the exercise. The target rep number is achieved in as short a time frame as possible, but usually with several “breaks” of 10-30 seconds. The weight can be manipulated within the set to try and keep things moving and manageable. Often we can time a density set and use that as a variable to try and improve in a later workout. So let’s say a lifter wants to do 30 dips at the end of a chest workout and it takes him 4:32 to complete all 30 dips. The next time he does dips he can try and complete the same total reps in less than 4:32 or do more dips (say 35) in the same amount of time. Generally, this protocol is only used on small muscle groups, bodyweight exercises, or isolation exercises. This is not a protocol we will be applying with Squats, Deadlifts, Presses, etc. But this protocol works well with abs, calves, biceps, leg extensions, leg curls, lateral raises, etc, etc. Density sets will improve two techniques that are common in bodybuilding. First is “restpause” sets. This is essentially when a target rep range is achieved with the same amount of weight and several breaks are taken on the way to that target rep number. For instance, a Density set of Barbell Curls using the rest pause technique might achieve 25 reps like this: 95 lbs x 12 (20 second break or 10 deep breaths) 95 lbs x 6 (20 second break or 10 deep breaths) 95 lbs x 4 (20 second break or 10 deep breaks) 95 lbs x 3 Another protocol used for higher rep density sets are drop sets. Drop sets are similar to density sets in that the weight is lowered each set, however, little to no rest is taken at each weight drop – usually 10-30 seconds at most. This is in contrast to descending sets where 23 minute rests are taken between weight drops. Drop sets are common on machine exercises where it is simple to change the weight via a selectorized stack and the lifter doesn’t have to change positions between sets. For instance, 50 leg extensions might be achieved on a selectorized machine like this: 150 lbs x 20 reps 130 lbs x 10 reps 110 lbs x 10 reps 80 lbs x 10 reps In this example the lifter only rests long enough to change the pin on the stack and perhaps grab a few deep breaths. The reality is that very often, high rep density sets will use a combo of rest-pause and drop setting to achieve the target number. The idea is not to get obsessive about exactly how the protocol is being performed or even the weight used. The idea is that very high density of work is done in a very short time. Focus on the muscle group and the pump being achieved. The weight is secondary in this protocol. More on supplemental and assistance lifts…… Supplemental and assistance exercises (exercises 2-5 each day) can be rotated in and out of the program often – even weekly if you like variety. These exercises are used to target weak links in the body and to develop individual muscle groups. We are working to create a “pump” in the muscle group, not just move weight from point A to point B. If you cannot feel the pump when using a certain exercise, then don’t use it. The pump is what helps us grow bigger – in conjunction with ever increasing loads on the barbell during our primary lifts. Now, taking all of these programming notes – let’s go back and apply the information to each individual training session to see how a typical 3 week cycle might look. Note that this example is not prescriptive for any one lifter. This is an example of a hypothetical 3-week training cycle. Week 1 (3x8) Monday - Chest & Biceps 1. Barbell Flat Bench Press 3 x 8. Full rest times between work sets. 5-8 minutes. 2. Incline Bench Press 3 x 8-12. Descending sets. 3. Dips: Density sets of 30-50 total reps. As many sets as it takes to achieve 30-50 total reps. Rest 1 minute between sets. 4. Barbell Curl 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets 5. DB Hammer Curl – 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets Tuesday – Legs, Calves, Abs 1. Deadlift 3 x 8. Full rest times between sets. 5-8 minutes. 2. Low Bar Box Squat 3 x 8. Descending Sets. 3. Lying Leg Curls – Density sets of 50 total reps. Start with a heavy set of 10-15 and use drop sets until 50 total reps are achieved. 4. Seated Calf Raise – Density sets of 50 total reps. 5. Hanging Leg Raise – Density sets of 50 total reps. Thursday – Shoulders, Triceps 1. Press 3 x 8. Full rest times between sets. 5-8 minutes. 2. Seated DB Press 3 x 8-12 (Descending Sets) 3. DB Lateral Raises – Density sets of 75 total reps. Start with 35s and move down rack as needed as drop sets 4. Close Grip Bench 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets 5. Cable Pressdowns 3 x 15-20. Descending Sets Friday – Upper Back 1. Pull Ups – Density sets of 50 total reps. As many sets as it takes to achieve 50. Use longer rest periods of 1-2 minutes between efforts. 2. V-Grip Pulldowns – 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets. 3. One Arm DB Rows 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets 4. Face Pulls 3 x 15-20. Descending Sets 5. DB Shrugs: Density sets of 50 reps. As many sets as it takes to achieve 50 with the 100 lb DBs. Saturday – Legs, Abs, Calves 1. Squats 3 x 8. Full rest times of 5-8 minutes. 2. Hack Squat 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets. 3. Leg Extensions – Density set of 50 reps. Perform first heavy set of 15-20 and then use drop sets until 50 total reps are achieved. 4. Standing Calf Raise – Density set of 50 reps 5. Decline Sit Ups – Density set of 50 reps. Week 2 (3x5) Monday - Chest & Biceps 1. Barbell Flat Bench Press 3 x 5. Full rests. 5-8 minutes. 2. Incline Dumbbell Bench Press 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets 3. Standing Cable Fly 3 x 12-15. Descending Sets. 4. Incline Dumbbell Curl 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets. 5. Standing Cable Curl – Density set of 50 reps. Drop set down the stack until 50 total reps are achieved. Tuesday – Legs, Calves, Abs 1. Deadlift 3 x 5. Full Rests. 5-8 minutes. 2. Stiff Leg Deadlift (elevated on 3 inch platform) 3 x 8. Descending Sets 3. Glute Ham Raise – Density set of 50 total reps 4. Seated Calf Raise – Density set of 50 total reps 5. Hanging Leg Raise – Density set of 50 total reps Thursday – Shoulders, Triceps 1. Press 3 x 5. Full Rests. 5-8 minutes. 2. Seated Machine Press 3 x 12-15. Descending Sets. 3. DB Lateral Raises 3 x 10-20. Descending Sets 4. Lying Tricep Extensions 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets 5. Dips – Density set of 30-50 total reps Friday – Upper Back 1. Chin Ups – Density set of 50 total reps. Take 1-2 minutes between efforts 2. Wide Grip Pulldowns – 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets 3. Barbell Rows 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets 4. Seated Machine Rows (w/ Rear Delt handles) 3 x 15-20. Descending Sets. 5. Strict Barbell Shrugs 3 x 15-20. Sets across with 225 lbs. Saturday – Legs, Abs, Calves 1. Squats 3 x 5. Full Rests, 5-8 minutes. 2. Leg Press 3 x 20. Descending Sets 3. Leg Extensions – Density set of 50 total reps 4. Standing Calf Raise – Density set of 50 total reps 5. Decline Sit Ups – Density set of 50 total reps Week 3 (3 x 2) Monday - Chest & Biceps 1. Barbell Flat Bench Press 3 x 2 2. Incline Barbell Bench Press 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets 3. Dumbbell Decline Bench Press 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets 4. Barbell Curls: Density set of 50 total reps with 95 lbs 5. DB Hammer Curls 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets. Tuesday – Legs, Calves, Abs 1. Deadlift 3 x 2 2. Goodmornings. 3 x 8 Descending Sets 3. Lying Leg Curls. 3 x 10-20. Descending Sets 4. Seated Calf Raise – Density sets of 50 total reps 5. Hanging Leg Raise – Density sets of 50 total reps Thursday – Shoulders, Triceps 1. Press 3 x 2 2. Seated DB Press 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets 3. DB Lateral Raises – Density sets of 75 total reps. 4. Dips 3 x 8-12 5. Lying DB Extensions 3 x 15-20. Use drop sets Friday – Upper Back 1. Pull Ups – Density set of 50 total reps. Take 1-2 minute rest between sets 2. V-Grip Pulldowns 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets 3. T-Bar Rows 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets 4. Reverse Pec-Dec Fly. Density set of 50 total reps. 5. DB Shrugs – Density set of 50 reps with 100 lb DBs Saturday – Legs, Abs, Calves 1. Squats 3 x 2 2. Front Squat on Smith Machine 3 x 8-12. Descending Sets 3. Leg Extensions: Density sets of 50 total reps 4. Standing Calf Raise – Density sets of 50 total reps 5. Decline Sit Ups – Density sets of 50 total reps Again, this 3-week template is not necessarily a prescription for any single lifter. This is merely an example to show you how a typical week might look with all the different potential variations in exercise selection and set/rep protocols. The only thing that is set in stone for each 3 week cycle is the 8-5-2 protocol applied to the first lift of each day. After that we can plug our favorite exercises into the 5-exercise template for each day and experiment with descending sets, drop sets, rest-pause sets, etc etc. There is almost no end to the potential variation within this fairly rigid template. A question many of you might have at this point is – “How do I choose between Descending Sets or Density Sets for my assistance exercises?” The truth is that there is no set formula. My personal preference is to use density sets for all abdominal and calf exercises, because at this point our lifter is tired and ready to be done with the workout! Density sets can be done very quickly. That, and abs and calves don’t necessarily require heavy training. I will use mainly descending sets of 8-12 reps and 2-3 minute rest periods for the “big” assistance lifts: chest presses, deadlift variants, squat variants, heavy rows, dumbbell exercises, etc. More density sets will be used on isolation work such as leg extensions, leg curls, bicep curls, tricep extensions, lateral raises, etc. But not 100% of the time. This choice is often made by feel within the workout, not every detail of every exercise need be planned in advance. Experiment with everything until you find what you like best. The KSC Method for Power-Building Diet You have to eat on this training program. Period. If you are not as committed to the diet as you are to the training program – don’t do this program. You’ll crash and burn – hard. That being said, you don’t need an overly complex diet plan to reap the benefits of this program. For most people, I recommend 5-6 meals per day. Below is the standard template from which I start most of my clients: Meal #1: 6 Whole Jumbo Eggs Oatmeal (minimum 1/2 cup dry) 1 Banana or Small Bowl of Berries Meal #2: 6-8 oz of Chicken Breast, Beef, or Grilled Fish White or Brown Rice (minimum 1/2 cup dry) “Free” Vegetables (spinach, broccoli,etc) Meal #3 (midafternoon): Protein Shake (1 or 2 scoops) 1 large apple or 2-3 small Halo oranges (a large apple eaten later in the afternoon helps to keep night time cravings down and prevents over eating at dinner). Meal #4 (Dinner) 6-8 oz Chicken, Beef, or Fish Sweet Potato or Regular Potato “Free” Vegetables Meal #5 (Before Bed or Mid-morning between breakfast & lunch) Protein Shake w/ spoonful of peanut butter ( 2 scoops whey) Meal #6 (Immediate Post workout) 1 scoop of Protein Powder + 60-80grams of Gatorade + 5g creatine After a week or so on this meal plan see what your bodyweight does and make a note of how you are recovering. There are some remedial action steps you can take to fine tune the diet to your needs. Implement 1 thing at a time and see what happens then either hold steady or implement another action step. If you feel under-recovered and/or your bodyweight drops too fast: Increase carb intake at breakfast and/or lunch to 1 cup dry of oatmeal and/or rice Increase fat intake. Add in supplemental fats to lunch and dinner in the form of a tablespoon of olive oil or other monounsaturated fats. Or eat more fatty fish and 80/20 ground beef and less lean proteins such as chicken and turkey. If you are gaining too much body fat: Implement 2-3 cardio sessions per week Remove carb sources from dinner time meal (no potatoes) and just do fibrous vegetables. Slightly reduce protein intake. Eat 4oz servings of lean meat with lunch/dinner and/or cut shakes from 2 scoops to 1 scoop, and/or reduce breakfast from 6 eggs to 4 eggs. For 90% of you, this is as much detail as you need for diet. Cardio Let me start by saying that I believe the fitness industry has made cardio training much more complex than it needs to be in the past few years. We used to just call cardio…..cardio. Now it has to be called “metabolic conditioning” or “energy system training” or some other fancy name to make it sound like you are doing something more than spiking your heart rate for a few minutes to burn some calories and boost your metabolism. And that is basically what were are doing on this program. We aren’t training for a 5-round UFC fight, so you don’t need to condition yourself with anything too complex. Use what you have available to you and get your heart rate up for 15-30 minutes 2-4 days per week. The main thing we want to avoid are modalities that will interfere with the high volume strength work we are putting in at the gym. So avoid long distance running. Avoid silly Crossfit WODs with high volumes of eccentrics. My favorites are sled pulling / sled pushing, walking on an inclined treadmill, elliptical trainers, regular stationary bikes, or Airdyne bikes. But basically, it doesn’t matter what you do. Really it doesn’t. If you can get your heart rate up enough to where it’s difficult to talk in full sentences (the old “talk test standard”) and you are pumping out a little sweat then you are doing your job. You don’t need a heart rate monitor. Steady state or HIIT intervals – again, it doesn’t really matter. We just want to get your heart rate up for an average of about 20 minutes. This will help to “smooth out” the wrinkles in your diet and it will increase your work capacity so that recovery (within workouts and between workouts) becomes easier. Cardio isn’t just about “training to get in shape.” Cardio also helps us “get in shape to train.” The workouts in this program are very hard. You need to be in shape enough to not only do these workouts, but recover from them. Some moderate cardio a few days per week can help with that. Deloading Every 6-12 weeks you need a week off. So basically you will run through 2-4 of these 3-week training cycles followed by an easier week. The main thing during the deload weeks is a drop in volume. All non-essential assistance work is dropped. Frequency will be dropped to twice per week and you will consolidate all major barbell lifts into these two days. Deadlifts will be dropped for the week. Example Deload Week: Monday Light Squat 3 x 8-10 (about 20% less than your last heavy 3x8 workout) Bench Press 3 x 8-10 (about 10% less than your last heavy 3x8 workout) Light Lat Work (pulldowns, rows, chins, etc) 3 x 10-15 (*nothing that taxes the lower back) Thursday Light Squat 3 x 8-10 Press 3 x 8-10 (about 10% less than your last heavy 3x8 workout Light Lat Work 3 x 10-15 Conclusion While there may seem to be a lot of confusing detail about this program – try and keep things simple and focus on the big picture items that matter most. There will be a tendency for everyone to immediately customize and adjust everything about this program. On some of the details that is fine, but there are a few items that are central to this program and its effectiveness. 1. The Training Split. This has been designed with optimal frequency and spread between sessions. Try and leave this alone. 2. The 8-5-2 protocol. This is optimal for long term strength and mass gains. Pay attention to the details of how this system operates. 3. Per session volume. Less work probably won’t yield enough volume for mass. The addition of more sets and/or more exercises will likely lead to overtraining or poor recovery. Have fun with this program. Everyone initially picked up a weight for the first time because they wanted to be both BIG & STRONG. Most of us that have trained for many years enjoy aspects of both powerlifting & bodybuilding without necessarily competing or specializing in either. Follow this program and observe your results for at least a few cycles and then make the necessary adjustments based on your experience and best judgement. I hope you enjoy the journey! In Strength, Andy Baker Garage Gym Warrior A complete 13-week training cycle for those of you training in a barebones garage, basement, or warehouse gym. All you need is access to a rack, a quality barbell, and your own bodyweight. Designed for lifters of any age who want to build muscle and increase strength with minimal equipment access A quintessential Heavy – Light – Medium 3 day per week strength program. If you've been wondering how to put this type of programming into practice – this program is for you! Heavy – Light – Medium is the best way to organize a full-body 3 day per week barbell program for lifters over 40. Everything included – no guess work. Exercises, sets, reps, percentages included for every training day of the program. Recommendations included for cardio and assistance exercises The following program is designed for those with a bare-bones list of equipment available to them. This is also appropriate for those that just prefer the simplicity of training the entire body with a minimal exercise selection and a simple to follow progression. Required Equipment Sturdy Power Rack Bench Press Unit or Utility Flat Bench Good Barbell(s) & Plates (including fractional plates) Chinning Bar Preferred (but not essential) Equipment: Bumper Plates EZ Curl Bar Dumbbells Cardio Equipment (1 piece minimum – Bike, Treadmill, Rower, etc) Blast Straps, TRX Straps, or Rings (for Bodyweight Rows if Chins cannot be performed). Program Overview The basic format for this program is the classic Heavy-Light-Medium template. HLM programs have proven themselves over the years to be effective for increases in strength & muscle mass. They are inherently flexible and adjustable for a range of individual trainees. Maybe most importantly, they are easier to recover from than other intermediate level programs like the Texas Method, making them accessible to trainees over 40 or those who have difficulty with recovery. This is basically a 12-13 week peaking cycle. There are 3 progressively heavier three-week strength building cycles that fluctuate volume and intensity (9 weeks total), followed by another 3-4 week peaking cycle, where you can test your lifts and get new maximums. Follow the testing week, it is recommended you take 1-2 weeks of easy/light training and then you can hop back into this for another 12 week run. Testing the Lifts At the conclusion of the training cycle it is recommended that trainees test new maximums in order to (1) measure progress (2) set up bench marks for the next training cycle. However, for those who train alone (in a garage or basement gym) it is recommended that testing be focused on two lifts – The Press & The Deadlift. Why? These exercises are safe to test alone. Missing a rep on Press or a Deadlift simply means putting the bar down. There is no danger of a fall or getting pinned under the bar. 1RM (1rep max) testing for the Squat can be dangerous, even if you have a sturdy rack with safety pins. Use caution if you choose to test the squat. Bench Pressing is potentially even more dangerous for 1rm testing if you train alone. There is a risk of getting pinned under the barbell. If you choose to test the Bench Press….please make sure your safety pins are set up accordingly. If you do not wish to test the Bench Press and the Squat, you can safely assume a conservative PR of about 5% per lift as a benchmark for your next training cycle (if you completed the 12 week program). It’s also tough to test 4 lifts for 1RMs within a week. Limiting testing to just The Press & The Deadlift will make the testing week much more simple. Prior to beginning your first cycle of this program you will need to know your current 1RMs for each lift. A conservative single on each lift is a sufficient starting place. Take 1 week prior to beginning this program as testing week to establish some conservative starting weights. DO NOT overestimate your current 1RM before starting this program. You will crash and burn midway through this program if you start off too heavy. Organization of Training / Weekly Schedule Monday: Heavy Squat Medium Press Medium Deadlift Wednesday: Light Squat Bench Press (serves as “light day” press, since it indirectly trains the press) Barbell Rows (serves as “light day” deadlift, since it indirectly trains the deadlift) Friday: Medium Squat Heavy Press Heavy Deadlift It is recommended that this organization is kept in place for the duration of the training cycle. This program has been properly designed to fluctuate stress evenly throughout the week and keep workouts to a manageable length. Garage Gym Warrior Program WEEK 1 Monday: Squat 4 x 6 x 70% Press 3 x 6 x 65% Deadlift 3 x 6 x 60% Wednesday: Squat or Pause Squat 2 x 6 x 60% Bench Press 4 x 6 x 70% Barbell Rows 4 x 8 (use a weight you can achieve all 4 x 8 with strict form) Friday: Squat 3 x 6 x 65% Press 4 x 6 x 70% Deadlift 1 x 6 x 70% WEEK 2 Monday: Squat 4 x 5 x 75% Press 3 x 5 x 70% Deadlift 3 x 5 x 65% Wednesday: Squat or Pause Squat 2 x 5 x 65% Bench Press 4 x 5 x 75% Barbell Rows 4 x 6 (use a weight you can achieve all 4x 6 with strict form) Friday: Squat 3 x 5 x 70% Press 4 x 5 x 75% Deadlift 1 x 5 x 75% Squat 4 x 4 x 80% Press 3 x 4 x 75% Deadlift 3 x 4 x 70% WEEK 3 Monday: Wednesday: Squat or Pause Squat 2 x 4 x 70% Bench Press 4 x 4 x 80% Barbell Rows 4 x 4 (use a weight you can achieve all 4x4 with strict form) Friday: Squat 3 x 4 x 75% Press 4 x 4 x 80% Deadlift 1 x 4 x 80% Squat 4 x 6 x 75% Press 3 x 6 x 70% Deadlift 3 x 6 x 65% WEEK 4 Monday: Wednesday: Squat or Pause Squat 2 x 6 x 65% Bench Press 4 x 6 x 75% Barbell Rows 4 x 8 (use a weight you can achieve all 4x8 with strict form – a little more than week 1) Squat 3 x 6 x 70% Press 4 x 6 x 75% Deadlift 1 x 6 x 75% Squat 4 x 5 x 80% Press 3 x 5 x 75% Deadlift 3 x 5 x 70% Friday: WEEK 5 Monday: Wednesday: Squat or Pause Squat 2 x 5 x 70% Bench Press 4 x 5 x 80% Barbell Rows 4 x 6 (use a weight you can achieve all 4x6 with strict form) Friday: Squat 3 x 5 x 75% Press 4 x 5 x 80% Deadlift 1 x 5 x 80% Squat 4 x 4 x 85% Press 3 x 4 x 80% Deadlift 3 x 4 x 75% WEEK 6 Monday: Wednesday: Squat or Pause Squat 2 x 4 x 75% Bench Press 4 x 4 x 85% Barbell Rows 4 x 4 (use a weight you can achieve all 4x4 with strict form) Friday: Squat 3 x 4 x 80% Press 4 x 4 x 85% Deadlift 1 x 4 x 85% Squat 4 x 6 x 80% WEEK 7 Monday: Press 3 x 6 x 75% Deadlift 3 x 6 x 70% Wednesday: Squat or Pause Squat 2 x 6 x 70% Bench Press 4 x 6 x 80% Barbell Rows 4 x 8 (use a weight you can achieve all 4x8 with strict form) Friday: Squat 3 x 6 x 75% Press 4 x 6 x 80% Deadlift 1 x 6 x 80% Squat 4 x 5 x 85% Press 3 x 5 x 80% Deadlift 3 x 5 x 75% WEEK 8 Monday: Wednesday: Squat or Pause Squat 2 x 5 x 75% Bench Press 4 x 5 x 85% Barbell Rows 4 x 6 (use a weight you can achieve all 4x6 with strict form) Friday: Squat 3 x 5 x 80% Press 4 x 5 x 85% Deadlift 1 x 5 x 85% Squat 4 x 4 x 90% Press 3 x 4 x 85% Deadlift 3 x 4 x 80% WEEK 9 Monday: Wednesday: Squat or Pause Squat 2 x 4 x 80% Bench Press 4 x 4 x 90% Barbell Rows 4 x 4 (use a weight you can achieve all 4x4 with strict form) Friday: Squat 3 x 4 x 85% Press 4 x 4 x 90% Deadlift 1 x 4 x 90% WEEK 10 Monday: Squat 4 x 4 x 80% Press 3 x 4 x 75% Deadlift 3 x 4 x 70% Wednesday: Squat or Pause Squat 2 x 4 x 70% Bench Press 4 x 4 x 80% Barbell Rows 4 x 8 Friday: Squat 3 x 4 x 75% Press 4 x 4 x 80% Deadlift 1 x 4 x 80% Squat 4 x 1-2 x 95% Press 3 x 2 x 85% Deadlift 3 x 2 x 85% WEEK 11 Monday: Wednesday Squat 2 x 2 x 75% Bench Press 4 x 1-2 x 95% BB Rows 4 x 6 Friday Squat 3 x 2 x 85% Press 4 x 1-2 x 95% Deadlift 1 x 2 x 95% Week 12 – Deload Tuesday Squat 3 x 3 x 80% Press 3 x 3 x 80% Squat 3 x 3 x 75% Press 3 x 3 x 75% Friday Week 13 – Testing Monday or Tuesday Find a new 1RM for the Press & Deadlift Thursday or Friday Find a new 1RM for the Squat & Bench Press (optional) or do lighter Squat/Bench workout for active recovery. FAQ Can I Train on This Program Just Two Day Per Week? Yes. There are two ways to go about doing this program with less frequency. First is simply to train a day, then take two days off, and then do the next workout. This will result in a varying schedule week to week, but will give you extra rest days. For example: Mon-Heavy; Thurs-Light; Sun-Medium; Weds-Heavy; Sat-Light; Tues-Medium; Fri-Heavy; Mon-Light; etc. The second method is just two fixed days per week. Good set ups include the following combination of days: Monday/Thursday; Tuesday/Friday; or Wednesday/Saturday. For example: Mon-Heavy; Thurs-Light; Mon-Medium; Thurs-Heavy; Mon-Light; ThursMedium. Etc. I Don’t Think I Can Recover From Deadlifting Twice Per Week, can I pull just 1x/week? Yes. Although if you stay with the program your body will adapt to pulling more frequently. If you want to pull just once per week, then don’t do any deadlifts on Monday. Replace those with something easier like chin ups, pull ups, or bodyweight rows. Choose an exercise that trains the back, but not the low back. You could also do your Barbell Rows on Monday and do your easier upper-back exercise on Wednesday. On Friday, you should do your single top work set as prescribed and follow that with back off sets using the loads/sets/reps that were prescribed on Monday. If this still feels like too much, just do one single work set, followed by one single back off set. Two other tips. Use straps on your medium deadlift day. This will help save the nervous system from too much stress. You can also use a “lighter” deadlift variant for equivalent volume on your Medium Deadlift day. So instead of Deadlifting 3x6, you could do RDLs or Stiff Leg Deadlifts that use lighter loads. In these cases, the % recommendation doesn’t apply and you’ll just have to select an appropriate load to use for those workouts. Power Cleans are also an option for your Medium Deadlift Day. Can I do Cardio on This Program? If so, how? Yes. Best days to do cardio are Tuesday, Wednesday, and Saturdays. I’d probably avoid any type of conditioning or cardio work on Sunday (the day before heavy squats) and maybe even avoid it on Thursday (the day before heavy deadlifts). Best results will come from 2-4 days per week of 20-40 minutes at a time, either on off days or post-workout. If you need it, how you do your cardio is less important than actually doing it. Basically any type of conditioning work is permissible provided it doesn’t interfere with your strength work. So that pretty much eliminates long distance running/jogging or any sort of Crossfit-style metcon with a lot of soreness producing movements like squats, push ups, lunges, etc. Basically just try to stick with conventional modalities and you’ll get better results. Any sort of stationary bike or Airdyne type bike, treadmills, ellipticals, and rowers are all very useful and simple to work with and probably fit nicely in your garage or basement gym. Again 2-4 days per week of 20-40 minutes at a time is an appropriate cardio prescription depending on your goals. At the low end we have 20 minutes 2 days per week just to maintain some work capacity in and out of the gym, and at the high end 40 minutes 4 days per week is appropriate for those who need to lose significant amounts of body fat while still having time and energy to train with barbells. Can I do Assistance Exercises on This Program? If so, what? Yes, but it should be limited. This program is pretty high volume already and assumes you don’t have much to work with other than barbells. However, there are other movements you may want to include. Just don’t get carried away and overdo it. All assistance work is 100% optional. Squatting 3x/week and Deadlifting 2x/week eliminates the need for any lower body assistance work or extra low-back training. Most assistance exercise will be for the upper body. If you want more lower body assistance type work, try dragging a sled or pushing a prowler for your conditioning work. Lying Tricep Extensions: use an EZ Curl bar or pair of Dumbbells. 3-4 x 10-15 reps. Do these on Friday after the main barbell work. Chin Ups/Pull Ups: use bodyweight or add weight if needed. 20-50 total repetitions after either or both of the main workouts on Monday and Friday. If only deadlifting 1x/week you can replace the 2 nd Deadlift workout with chins/pull ups. Bodyweight Rows: use straps, TRX cords, or rings. 50-100 total reps after the main workout on Monday or Friday. Use only if you cannot do chins or pull ups. Barbell or Dumbbell Curls: 2-4 x 8-12. Perform after any of the main workouts. Abdominals: basic sit ups or leg raises for 2-3 sets after any of the workouts. I can’t /don’t Want to Focus on the Press? Can I Make This a Bench Press Focused Program? Yes. In this instance you’d Press on Wednesdays, Bench Heavy on Friday, and Bench Medium on Monday. Light & Medium Days Just Feel Too Easy? Should I Make Them Heavier? No. But there are things you can do that will make light weights seem harder if you just really hate the idea of having an easy workout. Just remember that the purpose of the light and medium days are not necessarily to create tons of new stress so don’t kill yourself. 1. Bar Speed. Try exploding into the barbell on your light and medium exercises. Move the bar fast enough to try and make the plates rattle a little bit at the top. It may not move fast, but the act of trying to move it fast will make the exercise harder. 2. Pauses. Squats and Presses can be made much harder by lengthening the pause at the bottom of the rep. Be very careful with this on squats as Pause Squats are very stressful. You don’t necessarily have to pause every rep of every set. 3. Alter the Exercise. For instance, if the medium day deadlift feels way too easy, then pull from a small 1-2 inch deficit to increase range of motion. If you had a medium day Bench Press then perhaps do so with a Close Grip. 4. Shortened rest intervals. Shave a few minutes off your normal rest interval and quicken the pace on the light and medium exercises. Light & Medium Days Are Still Very Hard? Should I Make Them Lighter? Yes. In some cases this might be necessary. Right now, for most of the program the light days are 10% less than the heavy days and the medium days are 5% less than the heavy days (medium deadlifts are already at 10% offset). For some lifters it might be necessary to make light days 20% less than heavy days, and medium days 10% less than heavy days. Light and Medium days do not always feel easy, nor should they. But you should never be in danger of missing reps or having your form fall apart. If you miss reps or cannot maintain good form on your light or medium days then you need to increase the offset each week. Strength & Mass After 40 A complete 4-day per week training program for the over-40 lifter who still wants to build strength and increase muscle mass Periodized training plan for all major barbell lifts and complete template for assistance lifts used to increase muscle mass and sure up weak links Make use of the tried and true Heavy-Light system for optimal recovery and year round progression The following program was written in 2015 for an online coaching client of mine, prepping for the Starting Strength Classic. This is a contest of strength that focuses on the Squat, Standing Overhead Press, and Deadlift. In addition to building strength for the meet, my client also wanted to focus on some specific hypertrophy training to build more muscle mass and improve his physique. In his words “He wanted to instill some fear into his daughter’s boyfriends.” At the Starting Strength Classic meet, my client posted some very impressive lifts of a 495lb Squat, 240 lb overhead press, and a 565 lb deadlift. This program worked well for him and will work well for you. *Note: If you would rather focus on the Bench Press than the Press, that is an easy substitution. Simply plug in the Bench Press anywhere in the template where it calls for the Press, and relegate the Press as an assistance exercise. I have designed this program in a fashion that can be put into long term use. Ideally, you will be able to use this program for the next 6-8 months without serious modification. This is a classic 4-day Heavy/Light template. It will give you twice weekly exposure to the lifts without beating up your body, like a Texas Method style program is likely to do. I have you working on alternating rep ranges on a weekly basis to keep you from stagnating and hitting sticking points. The template is also arranged in a way that will allow you to add in a moderate-high volume of accessory work. The accessory work will be necessary to build mass and develop a better physique. I have designed the template for you to be able to add accessory work in for the triceps, biceps, chest, traps, and lats. After a few months you should appear to be more menacing to your daughter’s potential suitors Training Template Monday – Heavy Press / Light Bench Tuesday – Heavy Squat / Back & Biceps Thursday – Light Press / Heavy Bench Friday – Light Squat / Heavy Deadlift 3-week Rep Rotation Week 1: 3 x 5 (3 sets, 5 reps) Week 2: 3 x 3 (3 sets, 3 reps) Week 3: 3 x 1 (3 sets, 1 rep) All work sets are performed as SETS ACROSS meaning that you will achieve all your reps on all your sets with the same weight for each set, while taking 5-10 minutes between work sets. If you miss reps, then you will repeat that weight THE FOLLOWING CYCLE (NOT THE FOLLOWING WEEK). Below is a sample of 12 weeks on this program (4 continuous 3 week cycles) Week 1: 3 x 5 x 300 Week 2: 3 x 3 x 330 Week 3: 3 x 1 x 360 Week 4: 3 x 5 x 305 Week 5: 3 x 3 x 335 Week 6: 3 x 1 x 365 Week 7: 3 x 5, 4, 4, x 310 (bad workout – missed reps) Week 8: 3 x 3 x 340 (still added weight despite missed reps from last week) Week 9: 3 x 1 x 370 Week 10: 3 x 5 x 310 (repeats weight from week 7) Week 11: 3 x 3 x 345 Week 12: 3 x 1 x 375 So each rep range (5, 3, or 1) progresses independently of the other two rep ranges. If you get stuck on a certain rep range, then keep repeating that until you achieve your goal. You might get stuck on a certain rep range for 2 or 3 cycles, but progression on the other two rep ranges is what will get you unstuck. I like about a 5-10% gap between each rep range to start with. Although you can tweak this a little bit if the numbers don’t square. The stronger you are, the more you will hedge toward that 10% offset. The lower your lifts, the closer it might be to a 5% gap. The main thing is to not start too heavy and start missing reps on the first 1 or 2 cycles. It might take you a cycle to get through all the rep ranges and then you can go and tweak everything for cycle 2 if anything was either way too easy or way too hard. Each time through the cycle you would add anywhere from 2-10 lbs per lift based on the lift (press vs deadlift for example) and how easy or difficult each week was. This pattern is used for HEAVY lifts only. Light day lifts and accessory movements will use different set and rep schemes. Training Week Monday – Heavy Press / Light Bench / Triceps Heavy Press 3 x 5 / 3 x 3 / 3 x 1 Close Grip Bench Press 3 x 5-8* Lying Tricep Extension (LTE) w/ barbell or ez curl bar 2-3 x 8-10 or Cable Pressdowns Overhead Tricep Extension w/ dumbbell (single arm) 2-3 x 10-12 *CGB should be done in a range between 5-8 reps. Progress in weight when at least ONE set hits 8 reps, and no set drops below 5 reps. Rest 5 minutes between work sets. Tuesday – Heavy Squat / Upper Back Heavy Squat 3 x 5 / 3 x 3 / 3 x 1 Pull Ups, Chin Ups, or Lat Pulldowns 3-5 x 8-12 or 3-5 sets max reps of chins/pull ups Barbell Rows or One Arm DB Rows 2-3 x 10-12 Barbell Curls or DB Curls 3-4 x 8-12 *Rows should be done with straps Thursday – Light Press / Heavy Bench + Chest supplemental (hypertrophy) Light Press 5 x 3* Bench Press 3 x 5 / 3 x 3 / 3 x 1 Incline Dumbbell Press 2-3 x 8-10 Decline DB Press 2-3 x 8-10 (only a very slight decline; prop end of bench up on about a 3 inch platform for decline angle) *Light Press is done for 5 sets of 3 reps. Weight is 5-10% LESS than last heavy 3x5 press workout. Rest time is kept to 1 or 2 minutes and the focus is on BAR SPEED. So if you completed 3x5x185 last cycle then your light press will be about 5x3x165 with 2 min rest and an EXPLOSIVE bar speed. Keep the same weight for the whole cycle and work on increasing speed each week. Bump the weight up every time you complete a new 3x5 heavy workout. Incline & Decline combo will build the chest nicely. Friday – Light Squat / Heavy Deadlift Light Squat 5 x 3 (same protocol as light press. Use 10-20% reduction from heavy squat day) Deadlift 3 x 5 / 3 x 3 / 3 x 1 (5-10 minute rest between sets) Stiff leg Deadlift 1-2 x 6-8 (5-8 minute rest between sets) Barbell Shrugs 3 x 15-20 Deadlifts should use straps on the 5s and 3s week to save the CNS. Pull all your singles without straps. If grip is weak, then do your first set of deadlifts each week without straps, then use straps for sets 2 and 3. Volume deadlifts should always use straps or you will burn out your CNS. Stiff leg deads and shrugs should also use straps. Stiff leg deadlifts should be done STRICT with an emphasis on working the hamstrings. Go up in weight when at least 1 set hits 8 reps and the second set does not drop below 6 reps. Shrugs are not “power shrugs” as described in SS:BBT. These are just regular strict barbell shrugs to generate a good pump in the traps Deloading Every 2-4 cycles you probably want to schedule a deload week. The main thing on deloads is to drop volume and keep intensity high. Something like this: Monday – Heavy Press Press – 3 x 5 (5-10 lbs less than last cycle 3x5) Tuesday – Heavy Squat Squat – 3 x 5 (10-20 lbs less than last cycle 3x5) Thursday – Heavy Bench Bench – 3 x 5 (5-10 lbs less than last cycle 3x5) Friday – Heavy Deadlift Light Squat – 3 x 3 (not speed sets, just a few light triples for warm up) Deadlift – 1 x 5 (10-20 lbs less than last cycle 3x5) After your deload, you should feel good enough to jump right back into a new cycle starting with new 3x5 weight. Diet *The meal plan I provided to my client was designed as a “lean out” diet. He was carrying a little more body fat than he wanted and we used this approach to drop a little body fat while still training heavy. To drop down 10-20 lbs or so I’d look at cleaning up your carb sources a bit and monitoring things just a bit more closely as far as portion sizes and meal timing. You don’t need to get fanatical, but you need to be able to measure and tweak enough to slowly diet down without killing your strength. I like a template like this: Breakfast: 2 Scoops Whey in water or 1 Carton Liquid Egg Whites (drop the milk from your diet) ½ cup Oatmeal (measured dry) 1 Banana Lunch: 1 hand sized (palm and fingers laid out flat) chicken breast, steak, or fish filet ½ cup rice (measured dry) or Fist sized potato or sweet potato Salad or veggies (optional) Mid-afternoon: 2 scoops Whey in water 1 large honey-crisp apple (curbs appetite at night) Dinner 1 hand sized chicken breast, steak, or fish filet ½ plate of steamed, baked, or grilled vegetables. ½ a large avocado As you do this, see what happens to bodyweight after a week or two. If your bodyweight is falling too fast, then increase (double) your carb servings at breakfast and/or lunch to 1 cup measured dry of rice and/or oatmeal. If weight is still falling too fast or you aren’t recovering then add in 2 cups of low-fat cottage cheese as a sixth meal right before bed, about 2-3 hours after your dinner meal. If you still need more calories, like if you drop down but then want to start gaining a little back then increase your fat intake. The easiest way to do this is with a big spoonful of peanut butter at each meal (except for dinner where you can just have the whole avocado). Adds good quality fat and goes down easy. Heavy-Light-Medium Simplifying the Heavy/Light/Medium System – Part 1: Introduction & Squats As strength coaches, many of us were introduced to the concept of a “heavy-light-medium” training system by Bill Starr’s classic text The Strongest Shall Survive. Starr introduces the concept as being borrowed from the 1930’s from Mark Berry, who was himself a national champion weightlifter and prolific coach of the era. The concept was reintroduced to readers in Mark Rippetoe’s Practical Programming in 2006. A single system supported by three prolific coaches over the span of almost 100 years? Must be something to it. In fact, there is something to the system. I have been using the system with athletes and clients for a number of years with great success. The system is very simple and easy to manipulate, yet there continues to be some confusion in the strength training community regarding its application in practice. The Starr 5×5 Starr’s classic text was essentially a tutorial on his system of training large groups of collegiate athlete’s, particularly football players. Starr found that his athletes responded best to a high frequency and high volume of squatting, but performance was best when athletes were NOT handling maximum poundages at each session. Although Starr’s trainees may have been great athletes, most of them were probably not great lifters. And all of them were trying to balance the demands of their strength program with the demands of their sport, their academic life, and the typical social life of a male in his late teens, or twenties. This has much in common with most recreational lifters or sport athletes. For the seasoned competitive lifter in his physical prime, frequent handling of maximum poundages is both doable and necessary for optimum progress. But the majority of trainees who are training with barbells, will be doing so for a purpose other than competition in one of the strength sports. Family, careers, travel, age, injury, sports practices, and quite frankly a lack of discipline and motivation will prevent most trainees from doing all that is necessary to prepare for a schedule that calls for a maximum output at every session. The trainee simply can’t “get it up” to go all out, 3-4 days per week, physically or psychologically. Starr’s solution to this problem was the Heavy-Light-Medium training system. This gave the trainee the volume and frequency that they needed to drive progress, but only called for ONE heavy day each week for each lift. Being a proponent of the 5×5 system of training, Starr simply had all his trainees do 5×5 each training day (Mon-Wed-Fri), but fluctuated the amount of weight that the trainee used at each session. Simple. The routine Starr outlined in The Strongest Shall Survive was based on the Squat, Bench Press, and Power Clean, each done three times per week. Again, all exercises were done for 5×5 with the weight fluctuated throughout the week. I for one DON’T think that this is the best way to organize training, but Starr had to deal with training large groups of athletes in a small space. You need a simple system to do this, and I think this was probably the best solution he had. An example week under Starr’s system may have looked like this (using just the squat as an example): Monday: Squat 5 x 135, 165, 195, 225, 255 Wednesday: Squat 5 x 95, 125, 155, 185, 215 Friday: Squat 5 x 115, 145, 175, 205, 235 The same concept was applied to the Bench Press and the Power Clean. Again, I think there were some flaws in the program, namely the narrow selection of exercises. While I am certainly a proponent of squatting, benching, and cleaning, I think that most athletes, and certainly most average gym goers, would desire and need a wider variety of exercises for long term progress. Additionally, it is perfectly acceptable to venture outside the original 5×5 protocol. Because of the popularity of Starr’s work in TSS, many have come to associate the Heavy-Light-Medium scheme strictly with his version of the 5×5 protocol. Putting it into Practice I am fortunate enough to have my practice set up in a way that I work with my clients as individuals. I can apply the system in a way that suits them best, based on their own unique set of circumstances. In consecutive training appointments, I may see a collegiate football player and a 55 year old business man. Both can use the system, but of course it will need to be manipulated for each individual. The training system is extremely versatile, and is an easy way to organize training. In general, the best way to operate an HLM training program is with 3 full body workouts on a Monday/Wednesday/Friday type schedule. Each training session would consist of a Squat, a Pressing exercise, and a Pulling exercise. The exact exercises will be selected to fit the individual, based on their goals and level of advancement. The Exercises: Squats For the general strength trainee, I think that three back squatting sessions are best. The type of squat that I advocate is the version described in Mark Rippetoe’s Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training. Low bar, medium stance, just below parallel. This style of squatting has the benefit of allowing the most amount of weight to be used, and working the largest amount of muscle mass. This has a positive hormonal impact on the system as a whole, and will accelerate gains in both strength and muscle mass. Additionally, many do not give the squat its due regarding the technical nature of the lift. Like any other physical skill, squats need practice. Doing the lift 3 times per week (twice with moderate weights) gives the trainee the opportunity to hammer home perfect form and technique. This can be exceptionally beneficial for older trainees who tend to lose the “feel” of an exercise without some degree of frequency, but cannot manage multiple heavy sessions in the same week. This is also good for those who are particularly non-athletic and may have a hard time sustaining proper mechanics without regular practice. We have a rather insulting term in the personal training industry to describe this segment of the population: motor morons. The motor moron will benefit greatly from repeated exposure to this very technical movement. The benefit that this program has for athletes cannot be overstated. Non-barbell sport athletes must walk the delicate balance of training for their sport and training in the weight room. Many sports are of course quite demanding on the lower body and many athletes will not have enough reserves in their tank to squat heavy more than once per week. The HLM system allows the trainee to place their heavy squat day on whatever day of the week allows them to train in the most recovered state. For many this will be Monday since they are likely to have 1-2 days off during the weekend. During the rest of the week, the athletes will have to perform strength workouts, by and large, in a state of fatigue. The HLM system makes this a little easier to manage. On the light and medium days, the athlete will be focusing on form and technique, and SPEED. In TSS, Bill Starr talks about “making the plates rattle” at the top of the lift. For athletic training, I couldn’t agree more with this approach. Most sports are dependent on an athlete’s ability to demonstrate power – and this is a down and dirty way for the trainee to learn how to express their strength quickly. One area of this program which lacks some clarity is the degree of offset from the heavy day to the light day to the medium day. As with many things in weight training, there is no one answer that will work for everyone. One important concept to note is this however: the degree of offset will grow based on the absolute strength of the trainee. In other words, a 500 lb squatter will probably need a higher percentage offset than a 200 lb squatter. As a starting point though, start your light day 10-20% lower than your heavy day, and set your medium day 5-10% less than your heavy day. Stronger lifters will use the higher percentage offset, and weaker lifters (older trainees, women, etc) will probably use the lower percentage offset. Once you have your estimate, it is permissible to use your brain and your experience to adjust the numbers accordingly. Recent training history always produces better data than percentages. Percentages serve simply as reference points to give you an idea of where to set your numbers. Now, the alternate way to set up the HLM system for squats is to vary the exercises each day in a way that produces a HLM effect. For instance, a lifter could back squat heavy on Monday, front squat on Wednesday, and do a paused box squat on Friday. This provides the lifter with a little bit of variety in his programming and takes away the need for percentages. Using the preceding example, the lifter may squat for heavy sets of 5 on Monday, front squat for triples on Wednesday, and box squat sets of 5 again on Friday. The critical difference in this style of programming is that the lifter is actually giving maximum output on each day, but the load changes due to the nature of each exercise. This should be an important consideration when choosing which HLM method to select. Review Method 1: Static Exercise/Vary Load Example: Monday: Back Squat 3x5x405 Wednesday: Back Squat 3x5x325 Friday: Back Squat 3x5x365 Method 2: Varied Exercises Example: Monday: Back Squat 3x5x405 Wednesday: Front Squat 3x3x275 Friday: Paused Box Squat 3x5x350 Simplifying the Heavy Light Medium System – Part 2: Pressing In Bill Starr’s text, The Strongest Shall Survive, the basic pressing program was laid out much like the squatting program – a singular exercise, constant volume, and fluctuating intensity over the course of a week. In Starr’s program, the bench press was the exercise of choice for all 3 days. The benefit of this set up was that it was simple in concept and logistically feasible in a busy weight room with lots of athletes already occupying the squat racks. I also remember reading in an old issue of Ironman Magazine that Starr actually didn’t believe that benching for all three workouts was the best setup. He recalls that his primary reasoning for setting things up this way was (1) he wanted the simplest program possible, and (2) the popularity of the bench press among high school coaches made the program more marketable. Starr stated in the article that he actually would have preferred using the overhead press for all 3 days, but that he didn’t feel that his audience of high school coaches would buy into the program the same way. Fortunately we are not in a situation where we must choose just one exercise for the pressing program. The squat is unique in that it has no rivals when it comes to leg exercises. Front squats, box squats, overhead squats, etc, are all decent exercises, but none of them match up to the transformative power of just the basic back squat. Even in its light and medium versions, it could be argued that the squat is still a more effective tool than other variants of the lift. With pressing it isn’t quite so. Both the bench press and the standing overhead press (or just the Press) should be included and given their due attention in almost any basic strength program. It is hard to say which is better – the press is certainly more functional from an athletic standpoint, but the bench is equally as valuable in its allowances for much heavier loads. Even those who discount the functionality of the bench press should realize that regularly training the lift will help to drive steady improvement on the press. My Recommendations? My basic recommendation is that the heavy day exercise in the program always be bench presses. In almost every situation I can imagine the bench press will allow the trainee to use the most amount of weight relative to all other pressing exercises. For the light day exercise, I would always default to presses. Relative to just about any other type of barbell pressing variant, the strict overhead press will utilize the least amount of weight. So what about the medium day? There are a number of exercises to choose from, but for the sake of this article, I will go with my top 3 favorites: 1) Close Grip Bench Press. This option would be for those who want to focus on the bench press as their primary exercise. If I was using the HLM system for power lifting, this would be my exercise of choice. Close grip benching has been utilized by competitive power lifters for years as a primary assistance movement for competition style bench pressing. The close grip bench obviously stresses the triceps more than most competition style bench presses do, and because of this, the close grip bench also serves as a powerful assistance exercise for the press as well. Especially from the midpoint on up, the overhead press is largely dependent on tricep strength. Any exercise that allows the lifter to overload the triceps with heavy weights will have tremendous carryover to the press as well as the bench press. 2) Push Press. For the more athletically minded push presses are an excellent medium day exercise. This would be a good choice for many sport athletes, strongman competitors, Crossfitters, or anyone who wanted to put overhead pressing strength as their top priority. 3) Incline Presses. The incline press moves the bar at an angle that is directly in between the press and the bench press. Because of this, the incline could be considered the closest relative to a “hybrid” of the two exercises, and will have carryover to both the press and the bench press. Of the two, the incline press will probably have more carryover to the bench press simply because you are laying down against a bench, and the pecs are stressed slightly more than the delts are. However, those that regularly take out limit attempts on the press know that a significant amount of “upper chest” is utilized during reps that require a lot of layback to complete. Angles vary on incline benches, but lower inclines 30-45 degrees, will be much more helpful to bench presses, and steeper inclines (around 60 degrees) will be of greater benefit to presses. For a trainee who wants to focus mainly on mass and physique, I would choose Incline Presses over options 1 and 2. As most successful bodybuilders will tell you, inclines are the staple of their chest training workouts as opposed to flat presses. The look that comes with a full and developed “upper chest” will greatly improve the aesthetics in a bodybuilder, and go a long way in making the shoulder girdle appear bigger and wider than it may actually be. An important point to make is that the trainee does not have to just pick one exercise and stick with it for any length of time. It is perfectly acceptable to focus on one or the other for a period of a few weeks or months and then switch to another. It might even be a good idea to rotate the three movements on a weekly basis. This is an area where a lifter can permissibly sneak some variety into the routine to keep things mentally and physically fresh. As a final note, I intentionally did not include partial exercises into the discussion. Partial rack bench presses and presses are valuable exercises, but add a layer of complexity to the discussion that I didn’t want to get into. Depending on how the particular exercise is set up, partials may use more or less weight than their parent exercise, and this will affect its status as a heavy, light, or medium exercise. As a general rule, partial exercises could probably fit into most medium days just fine – even if the weight that was used was not technically “medium.” Some trial and error might be necessary. Simplifying the Heavy-Light-Medium Training System – Part 3: Pulling As with the squatting and pressing program, Starr’s basic template in The Strongest Shall Survive, called for just one pulling exercise to be done each week – the power clean. Like the squats and bench presses, power cleans were to be done for 5×5 arranged in a heavylight-medium sequence throughout the week. Supposing I was forced to choose just one pulling exercise to do 3 days per week, for a group of athletes, power cleans would probably be my exercise of choice. Deadlifts are the better strength builder, but doing them three days per week would be difficult for most athletes to recover from. Snatches are also a good exercise, but cleans can be done heavier, so they would win out in our hypothetical scenario. Fortunately we are not in a scenario where we must make this choice. Similar to the pressing program, most athletes will receive greater benefit from a more diverse pulling program. My favorite general pulling program is to deadlift on Heavy day, power snatch on the light day, and power clean on the medium day. To build a strong pull off the floor, we can’t just do the Olympic lifts. We need to be pulling heavy and deadlifts allow us to do this. By default, snatches are lighter than cleans and so the two Olympic variants fall neatly into the organization of this system. I’m a believer in variety when it isn’t just for variety’s sake. Having three different types of pulls for the athlete to work on prevents staleness and mental boredom from creeping into the program. Example set up of a basic pulling program: Monday: Deadlift 1×5 Wednesday: Snatch 5-8 doubles Friday: Power clean 5 triples There are however reasons to follow a different set up. A few options are presented below. Eliminate one Olympic variant from the program and do the other one twice. As an example, many trainees may be cursed with an anthropometry that makes effectively racking a clean difficult. Many lifters cannot properly receive the barbell on the shoulders, and are forced to catch the barbell with their hands, out in front of the body. This may be fine with lighter weights, but as the athlete’s strength grows, racking a heavy clean in this manner can lead to serious aggravation in the wrists and elbows. Or it may simply result in a lot of frustration due to frequently missing reps. In this scenario, the trainee may simply choose to deadlift once per week, and snatch twice – once heavy, and once light. The same scenario could potentially present itself with the snatch. Older trainees in particular may find that that proper racking of the snatch is difficult due to a lack of range of motion in the shoulders. Sometimes this can be remedied with stretching and practice, and sometimes it cannot. An example might be where there is a history of rotator cuff surgeries or arthritis. In this scenario the trainee may decide that it is more prudent to eliminate the snatch from his/her program and clean twice per week, once heavy, once lighter, and continue to deadlift heavy once per week. The benefit to this set up is that the trainee will likely get very good at whatever Olympic variant is getting trained twice per week. For this reason alone, some trainees who are capable of doing both lifts, may still only choose to concentrate on one or the other as to not spread their focus too thin. In this instance, it is my recommendation that the trainee select the clean over the snatch simply because you can do more weight, and heavier is generally better. On a programming note, the Olympic variants don’t need as much offset to be considered a “light day.” Taking 20 lbs off of a 400 lb squat doesn’t really make it a “light day” The lifter is still going to be exerting a tremendous amount of effort to squat 380 lbs. This isn’t necessarily true with the Olympic variants. The lifter who can clean 225 for triples will generally find 205 lbs fairly easy. So when selecting your light day weights, a 5-10% offset should be sufficient. As always, percentages are just guidelines. Always use your own experience and common sense to select the appropriate amount of weight. Two slow pulls per week, one dynamic pull. In this instance, the lifter may decide that cleaning and snatching isn’t doing much to drive his deadlifting weights up. Often times this is the case when a lifter has a very strong deadlift, and simply is not very good at cleaning or snatching. If technique on the Olympic lifts has the lifter muddled in say, the low 200’s, those lifts probably aren’t going to do much to drive a 600 lbs deadlift. In order to get his deadlift unstuck, the trainee may decide to implement another ‘slow’ pull such as a stiff legged deadlift, Romanian deadlift, or even a goodmorning. If the lifter decided to use these in his program, they fit neatly into the medium day. Example model: Monday: Deadlift – work up to a heavy set of 5 Wednesday: Power Clean – 6 doubles Friday: Stiff Leg Deadlift 3×5 Many lifters will find that their low backs simply cannot recover from two “slow” pulling days per week. Others will do just fine, but may only be able to do so for short periods of time, say 6-12 weeks. As a final note on the pulling program, let’s address a common issue for some very strong deadlifters. Assume that our hypothetical lifter is doing my standard program of pulling heavy on Monday, snatching on Wednesday, and cleaning on Friday. In our hypothetical scenario the lifter is getting mentally and physically fatigued from doing standard conventional deadlifts every single week and progress is beginning to stall. It may be in this trainee’s best interest to start working in a rotation of other heavy deadlifting variants. This will keep the heavy day ‘heavy’ but will begin to introduce some fluctuation in loading each week. This may break the lifter out of his rut. We see this same method in Mark Rippetoe’s Practical Programming. In Rippetoe’s text, the lifter alternates week to week between a heavy 5 rep set of rack pulls and an 8 rep set of halting deadlifts. These are done in place of the regular deadlift workout. Likewise, one of the corner stones of Louie Simmon’s Westside Barbell program is the continual rotation of various ‘max effort’ exercises in place of the standard competition lifts. In this scenario we are blatantly stealing from Louie, and using this concept on our heavy day. The lifter does not need 6,784 max effort exercises to choose from. My advice is to select a maximum of 4, including standard deadlifts. An example heavy day rotation might be: Week 1: Standard Deadlifts Week 2: Deficit Deadlifts (standing on a 2-4 inch block) Week 3: Rack Pulls Week 4: Stiff Leg Deadlifts In this scenario, the trainee would continue to snatch on his light day, and clean on his medium day. Programming Review Sample Heavy-Light-Medium Program (Powerlifting Focus) Monday /Heavy: Squat 3-5×5 Bench Press 3-5×5 Deadlift 1×5 Wednesday/Light: Squat 3×5 (10-20% offload from Monday) Press 3-5×5 Power Cleans 5×3 or 6×2 Friday/Medium: Squat 3-5×5 (5-10% offload from Monday) Close Grip Bench Press 3×5, 2×8-10 (back off set) Stiff Leg Deadlifts 2-3×8 The trainee might follow this relatively high volume program for 6-12 weeks, until performance can no longer be improved . The lifter would then transition into a phase of lower volume training (perhaps 4-6 weeks) where PR’s will be set on lower rep sets: Monday/Heavy: Squats: 5 heavy singles Bench Press: 5 paused singles Deadlifts: 1-3 heavy singles Wednesday/Light: Squats 3×5 (same weights as phase one) Press 3×3 Power Clean: 10 singles (on a 1-2 minute clock) Friday/Medium: Squats 3×5 (same weights as phase one) Close Grip Bench 3×3, 1×6-8 (back off set) Stiff Leg Deadlift 2×5 After setting some new PR’s, the trainee might take a deloading week of less frequent training, lower volume, and light weights, and then start back over at phase one again. Monday: Squats 3×5 Bench Press3x5 Power cleans 3×3 Thursday: Squats 3×5 Press 3×5 Stiff Leg Deadlifts3x5 This program is not meant to be a cut and paste prescription for anyone who wants to embark upon a HLM training program. It’s meant as a reference point as to how one might go about setting up their own training program using these principles. Exact numbers of sets, reps, and exercise selection are an individual consideration at the intermediate and advanced levels. Summary I want to make it very clear to the readers of this article that I am in no way degrading the work or the writing of Bill Starr. I am not qualified to do so, nor am I arrogant enough to try. The Strongest Shall Survive belongs on the shelf of any strength coach or personal trainer, and Bill Starr is an icon of the industry. I have it, and have read it many times. I am also well aware that the basic program I have referenced throughout this article, is not the only program presented in TSSS. My attempts in this article series to clarify and simplify, are meant to clear up some of the confusion and misinformation that has arisen and lives on the internet….NOT within the pages of TSSS. Starr’s program presented in TSSS was his program, for his audience, and for his trainees. What is regarded on the web as the “Starr 5×5 Program” was an example of a Heavy-Light-Medium program; it is not the Heavy-LightMedium program. Much of the confusion and misinformation that lurks in forums and articles on the internet has been propagated by those who have never read Starr’s text, and overall do not understand strength programming Structuring 12-week Heavy-Light-Medium Programs What Questions Does This Article Answer? How do you structure a 12-week HLM training cycle for yourself? Should you even be training with time sensitive “training cycles” or should your approach progression to be more open ended? I think by this time, everyone that reads me pretty much knows how I structure the basic template of a Heavy-Light-Medium training program for the training WEEK. But just so this article makes more sense to you, I’ll do a quick review (you can also read other HLM articles on my blog, and watch the HLM videos on my YouTube Channel for greater detail). We basically have a day for high stress (high volume, high intensity, or combo of both), a day of lower stress which is usually lower volume and lower intensity, and a day of medium stress which is medium in both volume and intensity). We can repeat the same movements over and over again each day, with just alterations in loading and volume, or we can use a variety of exercises that create a natural flow of heavy-light-medium (ex: Bench PressOverhead Press-Incline Press or ex: Back Squat-Front Squat-Paused Box Squat). As an example, a typical HLM week in one of my programs might look like this for the Squat: Monday: 5 x 5 x 80% Wednesday: 3 x 5 x 60% Friday: 4 x 5 x 70% But what about setting up training for the longer term, outside of just the structure of a given week? Or even more useful of a question, what about setting up a specific 12-week training cycle for yourself, using a Heavy-Light-Medium template? An Aside………(skip if you just want programming X’s and O’s) So let me back up a bit about my thoughts on “training cycles” and whether or not you should even be thinking about your training this way, as I believe this is a very important programming consideration. So I’m mainly speaking from my own experience of 11+ years of gym ownership and coaching and 7-8 years of delivering online based programming to my clients. I’m doing my best to examine how and why clients under both formats either fail or succeed. Here is what I have seen based on the behaviours and results of my clients and customers…….. When I am training a client in my gym and handling their programming for them on a day to day or week to week basis, I generally do not operate within the strict confines of a “time sensitive” program (unless they are prepping for competition, a sports season, etc). In other words, I don’t place them on a strict “12 week” or “8 week program” etc. The progression of load, the manipulation of volume, etc is all done on a more open ended week to week basis, as I watch how they are responding to the training. In other words, I don’t generally make drastic alterations to their programming if we are cruising. Cruising basically implies the trainee is steadily increasing loads on a weekly or “most weekly” basis, fatigue is manageable, etc, etc. In short – if they are making progress I don’t change much. I add or subtract volume as needed, alter exercise selection, etc, etc on a very individual timeline and quite frankly I am in a better position to do this than most of my clients are. My judgements aren’t diluted by emotion as much as theirs’ are, I have more experience coaching hundreds of people through similar programs, and I am there to either help push them through a particularly hard work out or week, or dial them back when they may want to keep pushing ahead. People being people, personality influences training. Some people need to be pushed, some people need to be reigned in, and this is part of the “art of coaching.” But not everybody is training in a private gym with a coach. In fact, most people are not. Most of my online customers are training alone, in their garage or basement gym, or in a globo type gym, surrounded by people, but still very much….alone. I have found that these types of trainees do better with a program that has a definitive start and end date. If you are running a race, it’s easier to know where the finish line is rather than just running until you feel like stopping, someone tells you to stop, or you collapse in a heap. We KNOW that consistency is the key to progress (more important than all the intricacies of programming details) and my observation has been that trainees are more consistent when they have the entirety of the program laid out for them in advance. This does not mean it can’t be tweaked or adjusted midway through, but at least you can tweak or adjust in a way that helps you reach the finish line as strong as possible, and maintains the spirit of the program. So that being said, the programs I design for online customers and clients almost always have a definitive starting point and ending point, usually 8-12 weeks. I have seen more people have success with this system than if the entire program is open ended. After the program is finished the trainee can go back and tweak some variables if needed, or run it again as RX’d if the program provided great results. Back to the Heavy-Light-Medium Nuts and Bolts…….. So basically I set up Heavy-Light-Medium Program two ways. First is more linear. It’s not linear in the way the Starting Strength Novice Program is (a true linear progression), but more or less the weight simply goes up a little each week and towards the end of the program, volume starts to drop. Fairly standard stuff that has been around for decades. I will start the program very traditionally with lighter weights and higher volume. The heavy days might start at 70% of 1RM, the light and medium days at maybe 60-65%. This allows people plenty of room to get adjusted to the volume and frequency. I HAVE to assume that people are adapted to neither when throwing a program out there to the masses. I have to assume that the trainee using this program is not used to squatting 3 days per week for multiple sets across, as many are not. In fact, many who start one of my programs may have been training very sporadically or not all prior to starting one of my templates and it would be malpractice on my part to assume otherwise. So I need to give them something very doable for the first week at least. The biggest mistake you can make is starting Week One way too heavy. If someone is coming to this program adapted to the volume and frequency, then they may perceive the first week as very easy, but that is less of a sin than crushing someone in the first week. In the linear HLM model, I will generally hold volume constant while increasing load steadily for about 6 weeks. It could be less or more, but 6 weeks is a good number for the average that seems to work well. So in the gym, I might extend a client out to 7-8 weeks if we are cruising, or cut them off at 4-5 weeks if they start to wear down. But 6 is a good place to start most programs. At about the 6 week mark I usually drop the volume of the heavy day (slightly) and start increasing intensity a bit more. The light and medium days will maintain their volume but I often decrease the intensity a bit. So if in phase one, we had a 10% reduction in load for the light day and a 5% reduction in load on the medium day, now we might increase those offsets to 20% drops on the light day and 10-15% on the medium day. This will allow you to maintain the volume you need on the light-medium days as heavy day volumes start to wind down. This also serves to provide a bit of a mid-program deload without letting off the gas too much in any one area. Over the next six weeks, I will continue to drop volume and increase intensity every 1-2 weeks on the heavy day while maintaining volume on the light and medium days. The final 1-3 weeks of the program will have trainees handling loads around 90%ish of their previous 1RMs for sets in the 1-3 rep range on the heavy day. I usually build in some wiggle room here in terms of rep range and total volume. By the time an intermediate trainee gets to say Week 9 of this program, they are probably stronger than when they started so “90%” of their old 1RM is not really 90% anymore. It may be less. In this case, we may be doing multiple triples across with the prescribed weights, but if not, I may allow them just to push singles or doubles. I want HEAVY, but I don’t want MAX EFFORT yet. So I adjust the rep ranges, but not the load. The load stays unless something has gone wrong in the weeks leading up to the heavy weeks. And on the final workout of the last heavy week prior to the deload, I will push their medium day pretty hard with multiple sets across in the 80-85% range. This can be a bit miserable, but it pays dividends in the end. We never fail reps, but during the last week or so the medium day gets “not so medium” and the program looks very much like a Texas Method template with one day dedicated to higher intensity singles and one day dedicated to high effort volume work. Then we deload and test new maxes in week 12 or 13. This type of program is very simple, very easy to operate and adjust, and works very very well. I’ve been using this method in the gym for over 10 years with lots of modifications over the years, but this is what I have settled on after much trial and error. Method Two – Cyclical HLM The second way I set up 12-week cycles is with multiple 3-week mini-cycles. This type of program is a bit more complex, but also works really well. Each 3-week mini-cycle starts higher in volume and lower in intensity and slightly bumps up intensity and lowers volume for 3 weeks, and then restarts again with a drop in intensity and an increase in volume. As an example a heavy day might operate like this for a 3-week cycle: Week One: 5 x 5 x 70% Week Two: 5 x 4 x 75% Week Three: 5 x 3 x 80% In the next mini-cycle you’d simply rotate back to 5×5 and bump the weight up a little bit, like this: Week Four: 5 x 5 x 72% Week Five: 5 x 4 x 77% Week Six: 5 x 3 x 82% After 2-3 of the 3-week mini-cycles I’d start to bring the volume down a little bit (on the heavy days) in prep for a testing date: Week Seven: 5 x 4 x 80% Week Eight: 5 x 3 x 85% Week Nine: 5 x 2 x 90% You could rotate through another higher intensity mini-cycle like this, or simply deload and test. So within each 3-week mini-cycle we have a move from higher volume / lower intensity to lower volume / higher intensity, but also each mini-cycle itself might follow this same pattern, leading up into a testing day in Week 12. It isn’t always good to necessarily drop volume at every 3-week mini-cycle, but usually there is an overall drop in volume at some point leading into a testing date. So which one to use? To be honest I don’t think it really matters that much. Unless you start the 12-week program way too heavy they both work really well so it becomes more of a personal preference. If you like more variation week to week, then cycle. If you want super super simple – go linear. We know that training can get stale mentally and physically if you repeat the same program over and over again, so I would suggest using both models at various points during the year. Client Q&A #3: Heavy-Light-Medium Set Up & Gym Time Saving Tip With the release of the Garage Gym Warrior program a few weeks ago, I’ve gotten several questions from those who are curious about the set up of the program – which is a very traditional Heavy-Light-Medium training template. It’s still not well understood that the Heavy-Light-Medium training template is NOT a specific program. It’s a means of organizing training. There is not one specific set/rep range or exercise selection that must be used for the program to work or to be called a “heavylight-medium” program. So the first “question” I’m going to answer is actually the summation of several questions I’ve received over the past few weeks on basically the same topic. “What is the best set/rep/exercise organization for a Heavy-Light-Medium program?” My favorite HLM set up uses a sets across approach for each of the 3 training days. The number of sets per day is varied according to the goal, as is the % intensity. I most often set the heavy day at 4 sets across. 5-6 total sets could also be appropriate, especially if lower reps are being used, but for the purpose of illustration, we will assume 5rep sets are being used. Remember, HLM programs are generally set up for populations that are a little older, are playing other sports, or just can’t recover from super-taxing barbell programs like the Texas Method. So for a heavy day 4 sets of 5 reps across is generally stressful enough. Light Days are done for 2 sets of 5 reps across at a 10-20% reduction from the weight used on the heavy day. Medium Days are done for 3 sets of 5 reps across at a 5-10% reduction from the weight used on the heavy day. Example: Monday: Squat 4 x 5 Wednesday: Squat 2 x 5 @ 80% of Monday Friday: Squat 3 x 5 @ 90% of Monday So yes, the Heavy Day (aka the “Stress” Day) is both the highest in volume AND load for any training day. This is a distinct difference from programming with the Texas Method, which separates out volume from intensity. The % offset for light and medium days is lifter and lift dependent. The bigger and stronger the lifter the greater the % offset will be. Males will use bigger offsets than females, and lifts such as Squats and Deadlifts use bigger offsets than Presses for instance. The 4 sets, 2 sets, 3 sets organization is used primarily when the same lift is done all 3 days of the week – for instance, back squats are typically used Monday, Wednesday, and Friday and we simply vary the load and the volume. However, for pressing movements, I either have people as press-focused or bench focused, meaning one lift is done on Monday and Friday, and the other lift is done on Wednesday. In this case, I usually do something more like this: Monday: Heavy Press 4 x 5 Wednesday: Bench Press 4 x 5 Friday: Light/Medium Press 3 x 5 @ 90% of Monday For Deadlifts, I do something a little different if we are going to deadlift twice in one week. Heavy Day is usually just 1 top set, and the medium day is 2-3 sets at about a 10-20% reduction in load. In the middle we do a lighter pulling variant like an Olympic lift, a barbell row, or perhaps even just some chins or pulldowns. Example: Monday: Heavy Deadlift 1×5 Wednesday: Barbell Rows 4 x 8 Friday: Light/Medium Deadlifts 3 x 5 @ 80-90% of Monday’s top set. There are of course, other ways to do this and you can read more about HLM programming in Practical Programming for Strength Training or in my 3-part article series here: Simplifying Heavy-Light-Medium. If you want a fully “done for you” Heavy-Light-Medium program that has been proven to work download this: Garage Gym Warrior. Question #2: “My Starting Strength workouts are bordering on 2+ hours per day, sometimes 3, should I change my programming up? I don’t have this much time to spend in the gym 3 days per week? Any tips?” There are a number of things you can do to speed up workouts and still get in the requisite amount of exercises and volume for a productive full body barbell training session. However, for me, the biggest time saver of all is fitting your warm up sets for the next exercise in between the 2nd and 3rd work set of the exercise you are currently performing. This obviously fills up some downtime between sets (should be minimum 5-8 minutes between work sets) but it also eliminates some dead time that occurs between exercises. Time you might otherwise get on your phone, chat with a buddy at the gym, or otherwise just fuck around between exercises. (As an aside – put your phone away while you train. You won’t die if you don’t text, email, or watch a video for 90 minutes. If you HAVE to have it for the use of the Starting Strength App or for videoing yourself, fine, but have the discipline to stay out of texts, email exchanges, or video watching. This will save time for most people as well). The way this will look in execution is something like this: Squat (warm ups + 1st and 2nd work sets) 45 x 5 95 x 5 135 x 3 165 x 1 195 x 1 225 x 1 250 x 5 (5 min rest) 250 x 5 (5 min rest) Start Bench Press Warm Ups…… 45 x 10 95 x 5 125 x 3 145 x 1 Finish Squat (3rd work set) 250 x 5 Start Bench Press Work sets (1st and 2nd work sets) 165 x 5 (5 min rest) 165 x 5 (5 min rest) Start Deadlift (warm ups) 135 x 5 185 x 3 225 x 1 255 x 1 Finish Bench Press (3rd work set) 165 x 5 Deadlift Work Set 285 x 5. Done. Heavy-Light-Medium - A principle with varying potential methodologies As I was working with a couple of clients yesterday, we discussed the nuts and bolts of their programming. Both clients, (one young, one middle aged) are using a heavy-light-medium approach to their training. Both are getting great results, but within the context of the HLM programming, they are each using two different methodologies. Client #1 - Young, Explosive, Athlete The younger client is 18. He's strong, very neurologically efficient, and therefore very explosive (he'll be going to OU next year on a full ride track & field scholarship). When you work with a guy like this you have to understand that they fatigue themselves easier than do less strong/less neurologically efficient trainees. This means you have to be careful with too much volume at work set weights, particularly if they are balancing sports practice and competition on top of training. Currently on his "Heavy Day" we work up to 3x3 across on the Squat and the Bench Press. Since he primarily competes in the shot-put these are two of his mainstay focus lifts. Usually after the Bench Press we do 1 or 2 sets of close grips as a back off set. For Light Day we do 3x3 on Presses, and then we Power Clean a bunch of singles or doubles - usually about 10 total sets. This is followed by working up to ONE heavy set on the deadlift of 1-3 reps. On Medium Day we do sets of 5 reps on the Paused Box Squat and the Incline Press. For the Incline, we usually do 3 sets of 5 reps across. Occasionally, I'll sub in a Dumbbell Incline Press for 3 sets x 6-8 reps. For the box squats we do 5 x 5 ascending in weight each set until we hit a top set of 5 reps. For sets 1-4 we really focus on exploding the weight up and making the plates rattle (a la Bill Starr). The 5th set is the only one that is truly "heavy" but never really in danger of a miss. I don't calculate tonnage and all that crap, instead I largely go by my own observation of my client at work and his feedback to me about which workouts are the most physically stressful. By far it's the 3x3 Squat workout on Monday, and everything else falls neatly into the HLM template. The whole week looks like this: Monday (Heavy) Wednesday (Light) Friday (Medium) Squat 3x3 Press 3x3 Box Squat 5x5 (ascending sets) Bench Press 3x3 Power Clean 10x1-2 Incline Press 3x5 (or DB Incline Press 3x6-8) Deadlift 1x1-3 Stupidly simple I know, but it works. I'm a fan of both simplicity and effectiveness so this works for me. Client #2 - Older client For the older client, a similar approach was taken using HLM, although in some ways this method looks a little bit like Texas Method programming. The reality is that it's kind of a blur between the two methodologies, but it's closer to HLM than Texas Method and I'll show you why in a sec. Monday is our "heavy" day, which can also be characterized as our "high stress" day. This is our money day that drives improvement across the board. Our Heavy Day is currently based around improvement of the client's ability to do 3 sets of 5 reps across on the Squat and Bench and 1 set of 5 on the Deadlift. Friday (Medium/Preparation) Monday (Heavy / Stress) Wednesday(Light) Squat work up to 1 set of 5 (about 10% Squat 2-3 x 2-3 (across) less than Monday) Bench 3 x 5 (across), 1 x 8- Press 3 x 5 (across), 1 x 8-12 (back off Bench 2-3 x 2-3 (across) 12 (back off set) set) Lat Pulldowns or Seated Cable Rows 4 Deadlift 1 x 5 Deadlift 1 x 1 x 10-12 Squat 3 x 5 (across) On our medium day we actually go heavier than on the heavy day, but the overall volume is much lower and therefore the stress is much lower. And, we only go marginally heavier than we did on Monday, maybe 2-3 lbs on the Bench and 5 lbs on the Squat and Deadlift. This is what makes it NOT the Texas Method which calls for a much bigger offset between Volume and Intensity Days and both days are pushing the limits of capacity. In this program, Friday is not pushing any limits. In a way, our Medium Day is more of Preparation Day, which gets this particular client acclimated and ready for the sets to come on Monday. I just noticed over time that he does better if he gets to "feel" the weight in his hands or on his back once before I ask him to push it for hard sets of 5. So the weight that we do on Friday is equal to the load we will do on Monday, but we only do it for 2-3 sets of 2-3 reps. Doing so gets his body and mind "ready" to blow it out hard on Monday for 5-rep sets across without overtaxing his body. For deadlifts, because they can be so stressful, we only pull for 1 x 1 with the weight we will attempt on Monday for 1x5. It’s as much a confidence builder as anything else. Here is an example of a 3-week progression using just the Squat as an example: Week Monday Wednesday Friday 1 2 3 3 x 5 x 315 3 x 5 x 320 3 x 5 x 325 1 x 5 x 285 1 x 5 x 290 1 x 5 x 295 3 x 2 x 320 3 x 2 x 325 3 x 2 x 330 So who would use this approach? Probably someone who struggles a little bit "mentally" with heavier and heavier loads each week. This approach allows you to "test" or "feel" the weight once in a "non-stressful" way before having to go all out with it for a new PR. These blocks of training won't last forever. Maybe we get a good 8-12 week run before we have to switch things up. If you're in a rut give something like this a try. It just might work for you too. Heavy-Light-Medium for Mass - An Old Method For New Gains For those of you who have read any of my writing you know that I am a big fan of the Heavy-Light-Medium system for strength training. For those of you who have not read my work….I’m a big fan of the Heavy-Light-Medium system for strength training. I of course take no credit for the development of the method. Most of us in the industry are familiar with the system thanks to Bill Starr’s classic text, The Strongest Shall Survive. For those unfamiliar with the methodology, Starr’s original program called for 3 whole body workouts per week consisting of the Squat, Bench Press, and Power Clean. All 3 lifts were trained on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday but with a fluctuating workload throughout the week. The Strongest Shall Survive was mainly targeting an audience of football players and football coaches, and for this purpose the program was fine. The program was simple and fairly easy to implement with a large group of athletes training in a small window of time. While the exact original program itself may not be the best in the world for adding mass, the basic concept behind the program can be extremely effective when applied properly. It has been my observation that many bodybuilders (and others training primarily for mass) over complicate their training, and do not spend nearly enough time hammering home the basics. By doing so they are leaving a lot of size on the table. Let’s examine a typical “bodybuilding” type of split: Monday: Chest/Biceps Tuesday: Legs, Abs Thursday: Shoulder/Triceps Friday: Back The primary problem with splits like these is that they tend to be very upper body focused. Legs are trained once per week, and the upper body is trained 3 times per week. You’ll never maximize the amount of muscle mass available to you by training this way. An alternative method using Heavy-Light-Medium….. Monday: Heavy Day Squat, Bench Press, Deadlift Wednesday: Light Day Light Squats, Military Press, Pull Ups Friday: Medium Day Medium Squat, Incline Press, Barbell Rows A full body split such as this keeps the focus on the big boys. Every workout the entire lower body, shoulder girdle, and upper back are trained with multi-joint exercises. Isolation exercises for biceps, triceps, abs, etc can be sprinkled in wherever, although it isn’t totally necessary to even do them. If you have never trained in a full body fashion like this, you will grow in response to this amount of stimulus. Especially in your legs Sets & Reps This type of programming responds better to low repetition training in the 4-6 rep range. The soreness created by higher rep, higher volume training tends to inhibit the effectiveness of this style of programming. Aim for 4 sets of 4-6 reps on each exercise. You may want to do higher reps for some back exercises (like pulldowns and rows) and may want to venture a little heavier on some of your heavy day exercises like Bench Presses and Deadlifts. Remember, this is more of a methodology of training than a cookie cutter program. Exact sets and reps, and exercise selection are highly individual and goal dependent. If this is your first introduction to squatting 3 times per week, I would suggest starting your light day with 20% less than your heavy day, and your medium day 10% lighter than your heavy day. It doesn’t matter that the squats aren’t to full capacity on these days….they are still going to yield more growth than repping out on the leg extension. The upper body movements use exercises that are heavy-light-medium by nature and using percentages is not necessary. Bench Presses are always the heaviest pressing exercise, military is the lightest, and Inclines are somewhere in the middle. You aren’t limited to just these movements though. After a while you might decide to switch things up and do this for your pressing exercises: Monday – Incline Press Wednesday – DB Shoulder Presses Friday – Weighted Dips For Back training you could change the exercises I listed above to this: Monday - Rack Pulls Wednesday - V-Grip Pulldowns Friday - T-Bar Rows If you get bored with back squatting 3 days per week you might try something like this: Monday – Back Squat Wednesday – Front Squat (quad emphasis) Friday – Paused Box Squat (ham, glute emphasis) Feel free to select the exercises that work best for you for each category (legs, shoulders, back). As long as you adhere to the heavy-light-medium pattern it should work just fine. Just don’t get too carried away with exercise selection and wander too far away from the basics barbell movements. Two Simple “Hacks” for Heavy-Light-Medium Programming As you know, Heavy-Light-Medium templates are one of my favorite programming structures for Intermediate level strength trainees. The concept is pretty simple, although the exact variables can vary quite a bit from person to person. This is one reason why people sometimes struggle with them. People like things delivered to them “cut & dried.” Given the choice, people will always go for something EXACT rather than flexible. And I understand that, however impossible it may be to actually deliver such a thing that works for every individual. My Garage Gym Warrior Program is an HLM model and is pretty straight forward and as “cut & dried” as it gets in terms of delivering exact exercise selection, sets, reps, and intensity prescriptions. It does tend to work pretty well for most intermediate trainees. If you want to design your own HLM program, you have to have a starting place for volume and I’ve got a pretty good structure that has worked well over the years as a pretty good starting point. You’ll likely have to modify over time, however, the changes tend to be small….shave off a set here or there, add a set here or there, modify intensity +/- 5-10% on any given day. Basically I like to start off with a fixed number of sets for each day and then modify the intensity accordingly. Heavy Day – 5 sets Light Day – 3 sets Medium Day – 4 sets If you are pretty strong and can produce a lot of fatigue on each exercise, or are older and struggle with recovery you may want to hedge volume down a bit to: Heavy Day – 4 sets Light Day – 2 sets Medium Day – 3 sets On the Heavy Day, aim for one big top set in the 1-5 rep range. This is your high intensity work for the week and the main metric by which to judge progress by week to week. Following the main top set, perform 3-4 back off sets at about a 5% reduction in load from the main set for about the same number of reps. So if you hit 405 x 5, then follow with 3-4 x 5 x 385 for the back off work. Of if you hit 455 x 3, then follow with 3-4 x 3 x 430-435 for the back off work. On the Light Day perform 2-3 x 5 at about a 20% reduction in load from your best sets of 5 work over the last several week. So if you’ve hit 405×5 on the Heavy Day, then do your light day for 2-3 x 5 x 325 or so. On the Medium Day perform 3-4 x 5 at about a 10% reduction in load from your best sets of 5. So based off a recent 405×5 heavy day top set, that’d be about 3-4 x 5 x 365. This works well as a starting point and then you can adjust from there. The other simple hack, is a solution to the “Mid-Week Pressing Problem.” Most people find the most struggles progressing whatever Pressing variation they are performing on Wednesday. For instance if they are doing the following: Monday – Heavy Bench Wednesday – Press Friday – Medium Bench They will progress fine on the Bench but perhaps struggle on the Press. An added day of Medium Pressing on Saturday works well. You can continue to do the Full Body Squat/Press/Pull sequence on Mon/Weds/Fri but on Saturday you can go in and hit whatever Pressing variant you perform on Wednesday again for a 5-10% reduction in load for about 4 work sets. While you are there, hit about 15-20 minutes of HIIT cardio and you have a quick 40 minute workout or so on a Saturday morning and you are out the door. If you want to add this second little “hack” to my Garage Gym Warrior HLM Program, I’ve had many clients do it and it works quite well. Aim for 4 x 5-6 (do not miss reps!) on Saturday of whatever you have chosen as your Wednesday Pressing variation and you’ll see almost immediate progress on that lift if it is feeling stagnate. Heavy-Light-Medium (16 FAQs) I’m not gonna waste time with an intro. We’re gonna go right into the heart of the issue with 16 of the most frequently asked questions I get about Heavy Light Medium Programming. If you don’t know what HLM programming is you can look it up in Practical Programming for Strength Training or search my blog for a bunch more articles (including a history/summary/overview) of the entire program. Should I do high intensity or high volumes on Heavy Days? You should do both. However you can arrange this in two different ways. The first method is to do a combination of intensity and volume in the same session. What I advise is working up to ONE top set in the 1-5 rep range. Following this, I’d suggest 3-4 back off sets of that are between 75-85% 1RM of between 3-6 reps per set. An easy to understand example might be 1 x 3-5 @ ~85% 1RM, followed by 3-4 x 4-5 @ ~80% 1RM. The other option is to train at a higher volume for a set period of time followed by an alternate block of higher intensity and lower volume for the heavy day. So perhaps the lifter trains for 4-6 weeks using 5 x 5 on the heavy day and then switches to 3 x 3 for a period of 3-4 weeks to try and really move some heavier loads. In this instance, the lifter may consider a very slight increase in volume of the light and/or medium day. Very simple alterations like this between volume and intensity can work very well for long periods of time. Except for when we may drop volume on purpose for the sake of increased loading, I generally aim for 20-25 reps or about 5 working sets on the heavy day. We may drop to just 3-4 working sets for the recovery impaired (older trainees or athletes), but we want volume fairly high today as it’s our primary stressor of the week. How much volume / intensity should I do on a medium day? As a general rule I like around 20 total reps for a medium day (4×5, 5×4, 3×6, or 10×2) all can work well on medium days. 4 sets of 5 reps is generally my “go to” middle of the road protocol for a strength athlete. Intensity will be about 5-10% lower than an equivalent amount of reps on the heavy day. For bigger/stronger athletes or recovery impaired trainees, I like a 10% drop in load from the heavy day equivalent. For sets of 5, this is generally work in the 70-75% range. How much volume / intensity should I do on a light day? As a general rule, I like around 15 total reps for a light day. 3 sets of 5 reps is the simplest way to achieve this unless there is a compelling reason not to. Intensity will be 10-20% lower than the heavy day at an equivalent rep range. If a 20% offset is used today, a 10% offset will be used for medium days. If a 10% offset is used for light days, a 5% offset will be used for medium days. For sets of 5, light day work is generally in the 60-70% range. Should I do the same 3 lifts all 3 days of the week or use variations of the lifts? For a new intermediate, keep it simple. Back Squat all 3 days until you get things figured out in terms of exact volume/intensity, etc that works for you. After you feel comfortable with the programming, then look at maybe adding Front Squats as a Light Day Squat or something like Paused / Box Squats for Medium Days. Change only one variable at a time. For Pressing, decide whether you want to focus on Bench Press or Overhead Press. Place the focus lift on the Heavy Day and the Medium Day (Mon & Friday most likely). Place the other lift on the “light day” or middle day of the week but train it heavy and for higher volume (so heavy 5×5 instead of light 3×5). Technically a violation of HLM in some instances if you want to be pedantic. But we don’t want to be pedantic so its okay. For medium day benching you can use Inclines, Close Grips, or Paused Benches as simple variants. For pulling, Deadlift heavy on the heavy day, but keep the volume down to just 1 main set. On the medium day, deadlift again but lighter and for more volume (usually 3-4 sets). Or you can stiff leg dead here. Light pulling days are best served by exercises that give the low back a rest – chins or rows rather than more deadlifts. How “heavy” should the light and medium variations be trained? Generally these lifts are trained “maximally” within the designated set/rep range. The nature of the loading of the lift itself (i.e. inclines use less weight then bench, front squat uses less weight than back squat, etc) will reduce stress so you don’t have to worry about “going light” or “going medium” or using %’s or RPE or any of that shit. If the program says “Incline 4 x 5” then just Incline for 4×5 with as much weight as will allow you to complete the volume in good form. Should I do all the heavy work on one day (i.e. heavy day) or spread the heavy work through the week? Unless you are a competitive athlete in another sport (more on this later) then it makes more sense to spread the stress around the week. Training the Squat / Bench / Deadlift all heavy in the same workout sucks big time for anyone but a beginner and it takes more time than most of us have. Instead you might do something like Monday: Heavy Squat / Medium Bench / Medium Deadlift; Wednesday: Light Squat / Heavy Overhead Press / Chins; Friday: Medium Squat / Heavy Bench / Heavy Deadlift. You can play around with this, but you get the idea. How do I know if my volume and intensity is set up correctly? Are you more or less making regular weekly progress on the Heavy Day and not feeling beat to shit? If you are making regular progress on the heavy day (are you setting a PR in some rep range?) then you are creating enough stress to drive adaptation. If you are making progress but feel like death, then perhaps you could be making the same progress with a bit less work. If you are not making progress then either (1) your program is too stressful (2) your program is not stressful enough. Which is it? Use common sense and instincts. If you are squatting 12 sets per week (M-5, W-3, F-4) then you don’t need more sets. Maybe you need more intensity on light or medium days. Do they feel too easy? They should be doable but challenging. Are your light/medium days ball busters? Missing reps? Drop the intensity. Or your programming strategy is just bad / unrealistic / non-existent. How should I progress on the heavy day? I like training up to one top set between 1-5 reps and then back off with 3-5 x 5 at about a 5% backoff from whatever my best set of 5 is. Here is an example of cycling between 5s, 3s, 1s, on the heavy day top set and then cycling the volume up in 3 week waves. Week 1: 5 x 80%, 3 x 5 x 75% Week 2: 3 x 85%, 4 x 5 x 75% Week 3: 1-2 x 90%, 5 x 5 x 75% In week 4 you can scrap the %’s and just bump everything up by 5 lbs and repeat the cycle. There is about 9,872 ways to perform a heavy day. This is just one of my faves that is very effective and very simple in practice. Can HLM be used with other sport training and/or conditioning? Yes, and it’s one of my favorite programs for combining with sports, conditioning, or military/LEO demands. The main thing that interferes with barbell training (mainly the squat) is running. So if an athlete has to run as part of their sport or training for their sport, then we simply need to arrange the week so that the Heavy Squat Day can be placed after a day of complete rest or the lightest day of the week in terms of running/conditioning/practice. If the athlete has to run prior to a light/medium day it’s usually no big deal. Decrease the % offset as needed to deal with the fatigue so that you can hit your light/medium day volumes without misses or insane amounts of effort. Use the day prior to your heavy day (hopefully a rest day!) to really focus on carbohydrate intake in order to make sure you are glycogen loaded. Carb loading on a rest day prior to heavy training is far more effective than carb loading the day of the heavy training event. Not sure why performance athletes continue to screw this up. Can HLM be used for powerlifting / weight lifting? Yes. Setting the program up for Power lifting is relatively easy. For weight lifting, you can use HLM concepts for Squatting and Pressing, but the competition lifts probably need to be trained heavier and more frequently than a standard HLM program calls for. Can HLM be used for bodybuilding / mass gain / physique training? Yes. I recommend using a wider variety of exercises than the standard template calls for and focusing on volume pretty much across the board. Something like Monday: Squat/Bench/Rows; Wednesday: Press / Deadlift / Front Squat; Friday: High Bar Paused Squat / Incline Bench / Pull Ups Can I do assistance work on HLM training? Yes, but just watch your soreness patterns and recovery. High volume of assistance work is difficult to recover from on a 3-day per week full body routine. Add 1 movement per day, adapt, and then add a little bit more as work capacity improves. Tip: reserve all direct tricep work for Fridays when you have 2-days to recover. How can I focus equally on Pressing and Benching? Do I have to prioritize? Some lifters have gotten better progress on their pressing exercises by adding a 4th “1/2session” on Saturdays. So if a lifter is doing this: Mon-Bench 5×5; Weds-Overhead Press 5×5; Friday-Medium Bench 4×5….then on Saturday he can go in and do a light-medium Overhead Press workout for 3-4 x 5 (-5-10%) In a recent HLM training cycle in my Baker Barbell Club Online, I had my members run an HLM pressing cycle that went like this: Mon: Heavy Bench, Weds: Heavy Press, Fri-Medium Bench Mon: Heavy Press, Weds: Heavy Bench, Fri-Medium Press It worked really well. What about the use of the olympic lifts with an HLM program? Power Cleans and Power Snatches work well for the general strength or power athlete and fit perfectly in an HLM template. Deadlift on Heavy Day, Power Snatch on Light Day, and Power Clean on Medium Day. I have run that variant for years at my gym with track and field athletes, football players, Crossfitters, and general strength athletes who just like the olympic lifts, etc. Can I use HLM principles with other intermediate programming, like the Texas Method? Yes. Many lifters don’t have success with the Texas Method for their Squats and Pulls, but really like it for Benching and/or Pressing. In this case, when using a 3-day per week full body plan, it’s easy to blend the two approaches. Squat and Deadlift according to an HLM model, and Bench and/or Press according to the Texas Method. Can I train with HLM just 2 days per week? Dr. Jonathan Sullivan at GreySteel Strength & Conditioning has had success with his Master’s athletes running an HLM program across a two day week like this: Mon-Heavy, Fri-Light, Mon-Med, Fri-Heavy, repeat. My preference is simply to train Heavy once per week and then Light/Medium on the other day of the week if you can only get into the gym twice per week. Still have more questions???? My Garage Gym Warrior Program is an easy to use Heavy Light Medium Program that is essentially “done for you” in terms of sets and reps. It’s my best selling program and reviews are 99% positive in terms of improvements in strength. This is a great way to get your feet wet with HLM. Go here: Garage Gym Warrior HLM Program Heavy-Light-Medium Programming Tips I thought I'd give you a couple of tips that can really help improve your results if you're following one of my two HLM programs: Tip #1: Repeat the Wednesday Pressing Variation on Saturday and Couple With a Conditioning Session In a basic 3 day per week HLM program we generally prioritize either the Bench Press or the Press and train that movement 2 days per week on Monday and Friday. The opposing lift gets trained on Wednesday. Sometimes, when a lift is just trained 1 time each week it doesn't make as much progress as the lifts that are trained 2-3 days per week. A very simple solution is to go in and train that lift again on Saturday. I usually recommend 4 to 5 sets of 4-6 reps with about 5% less load than you used on Wednesday. This allows you to Press and Bench each 2 times per week. Since you are only going in to do 1 upper body lift you should have plenty of time to add in 20-40 minutes of cardio/conditioning work to make your trip to the gym worth the drive. Adding in the conditioning work can have several benefits including better recovery between sets during your week with the possibility of shortening average session duration. Tip #2: Skip the "Peaking Phase" in each program. Both the GGW program and the Classic HLM have 6-9 week volume accumulation phases followed by 3-6 week tapering / peaking phases that culminate in a testing week. It actually isn't always necessary to taper and peak every 6-9 weeks. If you make all your sets and reps in the 6-9 week accumulation phases you can probably "assume" a 5-10 lb increase in your 1-rep max and simply repeat the accumulation phase several times before you taper and peak. At this point you don't even have to use the percentages that we use on the initial run of the programs. If you keep detailed logs (which you should!!!) then you can simply go back through the program and increase the weight of each workout by 5-10 lbs and you should be golden. You can also make small tweaks to the program such as adding or subtracting sets or switching out a light or medium day exercise with a variation of that lift (i.e. front squats for light squats or incline press for medium bench, etc, etc). Texas Method Texas Method Overview Despite its popularity and widespread use there exists some persistent confusion as how to best navigate through all the possible twists and turns of the Texas Method. The Texas Method is the enigma of intermediate programming. No other particular program has been as single-handedly responsible for some astonishing examples of extended intermediate progress while simultaneously burying so many others in just a few weeks’ time. Texas Method is pretty much Pass/Fail, and unfortunately there are too many examples of Fail from its users. There are two main reasons for the high crash-and-burn rate among trainees and coaches. First, inappropriate usage. As we have stated before, the Texas Method is a lifter’s program. It’s very effective, but very hard. Even when done appropriately, recovery from the Texas Method is difficult to manage and it’s likely that only someone with competitive aspirations will take the time and effort to consistently manage their calories, sleep patterns, and lifestyle choices to make the program work. The workouts can be long and drawn out, and the average working adult over 35 years of age probably cannot commit the time or the energy to do the program properly. So if you are over 35 or 40 years of age, and you consider yourself to be a “recreational lifter,” then it’s probably best that you consider a Heavy-Light-Medium Program or a Split Routine training model. Second, even for those who are good candidates for the traditional Texas Method training model, there is rampant misapplication of all the training variables. This is especially true in the period of transition from the novice program to the Texas Method. If you don’t navigate this timeframe correctly you can very easily sabotage your future on this program. The area where we see the most mistakes made on the Texas Method revolve around the Intensity Day and a misunderstanding of what exactly the Intensity Day is, how it is supposed to work, and how it relates to the volume day workloads. As traditionally understood, the Volume Day of the Texas Method is the primary “stressor” of the week. Having by far the highest workload in terms of tonnage (the total sum of sets x reps x load), the volume day is our primary “disrupter” of homeostasis, which is necessary for continuous adaptation. Many have come to think of the Intensity Day as simply the “expression” of new adaptation caused solely by the stress of the Volume Day. This is the truth, but not the whole truth. The Intensity Day is also an extension of the stress created by the Volume workout. Intermediate trainees need exposure to the stress of high volume workouts, but they also need the exposure to extremely heavy loads if increased force production is the ultimate goal of the program. And since it isn’t really feasible to get all of that work into a single session, we have split the week into high volume work and high intensity work. So the Intensity Day is not necessarily just an “expression” of the adaptation from the stress we applied on Monday’s volume day. Although it is that, it is also a stress in and of itself. While the nature of the stress is different than Monday’s 5x5, one all out herculean set of 15 reps is certainly a catalyst that contributes to the adaptation of greater force production. And just as Monday’s 5x5 contributes to your ability to perform a new 5RM, 3RM, or 1RM on Friday, the stress of Friday’s high intensity set or sets will contribute to your ability to perform a new 5x5 max on Monday. We’d like to think that the whole Stress-Recovery-Adaptation cycle is simply confined to a nice and neat Monday through Friday weekly training cycle, that simply repeats itself starting every Monday. The reality is that Stress, Recovery, and Adaptation are continually happening all the time. Our brains don’t like the fact that there is a massive amount of fuzzy grey area when all of these things actually take place, but that is in fact the case. We stress ourselves on Monday with a very high volume of work at a moderate intensity and we begin the recovery process as soon as we leave the gym. We add another stress on Wednesday. Even though this is a light day, and the dose of stress is relatively small, we haven’t yet recovered from Monday, so we are still adding stress to the recovery load. Although we may or may not be fully recovered from Monday and Wednesday, we are recovered enough by Friday to add yet another stress on Friday, although we must alter the nature of that stress. Experience has shown that a higher-intensity low-volume session works best here. Over the weekend, we recover from the very heavy loads we lifted on Friday with the hope that the exposure to those extremely heavy loads will aid us in our volume day efforts the following Monday. And so the cycle is continuous and we probably don’t have a precise handle on the exact time frame of how all of this occurs. We just know that we are in a pretty much constant state of applying stress, expressing adaptation, and recovery. And if all the variables are managed correctly, we know that it works. Understanding the Texas Method Intensity Day by Andy Baker Managing Intensity Day Correctly The most widely used iteration of the Texas Method Intensity Day is to try and set a new 5RM every Friday. This is balanced with a corresponding cluster of 5-rep sets on Monday (think 5x5), generally at about a 10% reduction in load. The context of this particular iteration of the program is a very important consideration. The combination of 5s on both volume and intensity days has some pros and cons. The best part about using 5s on both volume and intensity day as the first iteration of intermediate programming is that it makes an extremely easy transition for a trainee coming off the novice program. This is especially true for inexperienced novices (which is most of them) who may be working in the absence of a qualified coach or programming advisor. We have a pretty good formula in place for transitioning smoothly out of the novice program and into the Texas Method. The simplest method is to simply take your last best 3x5 performance from the novice program and set that weight as your next 5RM workout. If you want to be aggressive, perhaps you set that 5RM just a very little bit heavier than your last 3x5 workout. For instance, if your last best 3x5 workout was 305, then you might plug in 305 or 310 as your very first intensity day workout for a single set of 5. Now, it is very important to remember that we are not basing our intensity day workout off of the last attempted 3x5 workout, but your last completed 3x5 workout. If you ended your novice linear progression on a Friday with 305 for 2 sets of 4 and a set of 3 rather than 3 sets of 5, then you can’t use 305 for your intensity day 5RM. Instead, track backwards through your training log to your last successfully completed 3-sets-of-5 workout. Here is an example of how to properly transition, using a fairly aggressive approach: Monday Last week of Novice Linear Progression 300x5x3 First week of Texas Method 280x5x5 Wednesday 270x5x2 (light day) 255x5x2 (light day) Friday 305x5x3 310x5 Here is a second example of a transition from a novice linear progression that did not end quite so smoothly: Monday 2nd to Last week of Progression Novice Linear 290x5x3 Last week of Novice Linear Progression 300x4,4,4 First week of Texas Method 265x5x5 Wednesday 260x5x2 (light day) 265x5x2 (light day) 240x5x2 (light day) Friday 295x5x3 300x5,4,4 295x5 As alluded to earlier, this approach is fairly aggressive. It’s important to understand that the novice who is grinding to a halt at the end of his linear progression is a very tired lifter. At this point he has been pushing against very heavy sets of 5 across for the last 4-6 months in most circumstances. Mentally and physically, he is fatigued. Not only will the trainee welcome some changes in the structure of the programming, he could probably use a little bit of a break as well. Now, for a novice or early intermediate, it’s rarely a good idea to just take a week or two off from training. He’ll detrain and lose some of the ground he has fought hard to gain. But 1-2 lighter weeks is probably a good idea in most circumstances. So the first two weeks of the Texas Method aren’t necessarily going to be easy but we are not aiming for new personal records. We’ll save those for week 3 or 4 of the program. We’ll ensure this happens by setting the new target 5RM for week 4 of the new program. Then we work backwards a bit each workout until we arrive at the work set weights for week 1. Here’s how this looks: Monday Last week of Novice Linear Progression 300x5x3 Texas Method Week 1 Texas Method Week 2 265x5x5 270x5x5 Wednesday 270x5x2 (light day) 240x5x2 245x5x2 Texas Method Week 3 275x5x5 250x5x2 Texas Method Week 4 280x5x5 255x5x2 Friday 305x5x3 295x5 300x5 305x5 (ties old max) 310x5 (New 5RM) 3x5 This strategy borrows a bit from more advanced programming models that rely on long blocks of volume accumulation (several weeks or months usually) followed by longer blocks of volume reduction and deloading that culminates in a peak at the end of a training cycle. The trainee would then repeat another long drawn-out volume accumulation phase, followed by another deload and peaking phase. This will not be the strategy for the intermediate trainee except during this short term transition phase. After a brief (1-3 week) respite allows for some dissipation of accumulated fatigue from the stress of the novice linear progression, we will follow a weekly progression and attempt to display new performance increases on a weekly basis. As mentioned previously, there are some drawbacks to the use of 5x5 on volume day and an attempted new 5RM on intensity day. The main drawback is that this phase does not last very long before new 5RMs are no longer possible. Although this is discussed at length in Practical Programming for Strength Training, it seems to be a point that did not sink in well for many trainees. The continued reliance on the exclusive use of the 5-rep set is not a longterm intermediate strategy. New 5RMs on a continual weekly basis are generally not possible for more than about 4-8 weeks. To state it very simply, the training stress generated by 5s will have grown rather stale. Physically and mentally, the trainee needs a new stimulus and a new challenge. At this point, 5s will still be used for volume day, and the intensity day workouts will begin to utilize sets in the 1-3 rep range. At this stage in the trainees lifting career, higher force production work on a regular basis will be needed if continued progress is to occur. Not only will the trainee need to physiologically adapt to the unique stresses of loads in the 90-100% of 1RM range, but he will also need to start developing the skill of grinding against very heavy loads that move slower and challenge mental fortitude and focus. Again, the Texas Method is a lifter’s program, and lifters must develop not just the strength, but also the skills needed to work with extremely heavy loads. Once a new 5RM is no longer possible on a weekly basis, then the trainee will essentially split up the volume and work towards putting more and more weight on the bar using two triples instead of a single set of 5. Ideally the change in rep-range will occur because an experienced coach or programming advisor pre-emptively makes the change before failure occurs, but this is not an exact science and often the trainee will be forced to switch to triples because he failed their 5RM attempt. Following this change, the trainee can expect maybe 3-6 weeks worth of progress using triples, and then he will switch to the use of doubles – usually 2-3 sets of 2. Again, these programming changes work best when they are made before failure occurs on the triples. When working with doubles, again the trainee can expect maybe a few weeks of progress and then there will be another reduction in reps, this time to singles across – usually 3-5 sets of 1 rep. Perhaps 3-4 weeks of singles across will likely culminate in a session where he achieves just one heavy single. This will be the closest the trainee has come to establishing what can be considered a true 1-rep max. This cannot be repeated the following week. In Practical Programming for Strength Training, we refer to this strategy as “Running It Out.” Essentially a gradual increase in weight every single week as the target rep range is reduced every few weeks to accommodate the heavier loads until the trainee can no longer reduce reps or add weight. It should be understood that we only really apply this strategy one time. Once the trainee has successfully “run it out” from 5s down to 1s, then the next step is to incorporate a 3-week rotation of 3s, 2s, and 1s. From this point forward, as long as a Texas Method-style programming model is used, the trainee will work in 3-week waves on the Intensity Day, although there is some variability in terms of rep ranges used and the exact volume of the Intensity Day work sets. More on this later. As a slightly more advanced, stronger, and experienced trainee there will be a need for some weekly fluctuation in the nature of the stress applied to the trainee each week. There exists some confusion within the community as to how a 3-week wave differs from an advanced training model. The hallmark of intermediate training models is that there is progress – new PRs – on a weekly basis. Regardless of whether that progress comes in the form of a new maximum triple, double, single, or set of 5 is irrelevant. New PRs at any rep range on a weekly basis is intermediate level training. This is a stark difference from the advanced trainee who may only be setting new PRs once every 4-8 weeks. Once the trainee has “run it out” and culminated in a maximum single or cluster of singles, then he cycles back to triples for the start of the new programming model using a weekly rotation of rep ranges. The best way to go about this is to refer back to the training log and look at the last completed triples workout from several weeks back. The trainee can aim for a new PR with a load that is slightly heavier than where he left off. So if the last completed triples workout was 350x3x2, then it would make sense to attempt 355x3x2. The following week the trainee would add about 10 pounds to the bar and attempt 365x2x2-3 (i.e. 2-3 sets of 2 reps). The following week (week 3) the trainee would add another 10 lbs to the bar and attempt 375x1x5 (i.e. 5 sets of 1 rep). On week 4 he would return to triples for a conservative PR of 360x3x2. Week 5 is 370x2x2-3. Week 6 is 380x1x5. Below is a glance at approximately 21 weeks’ worth of training using a 3-week wave: Week 1: 355x3x2 Week 4: 360x3x2 Week 7: 365x3x2 Week 10: 370x3x2 Week 2: 365x2x2-3 Week 5: 370x2x2-3 Week 8: 375x2x2-3 Week 11: 380x2x2-3 Week 3: 375x1x5 Week 6: 380x1x5 Week 9: 385x1x5 Week 12: 390x1x5 Week 13: 375x3x2 Week 16: 380x3x2 Week 19: 385x3x2 Week 14: 385x2x2-3 Week 17: 390x2x2-3 Week 20: 395x2x2-3 Week 15: 395x1x5 Week 18: 400x1x5 Week 21: 405x1x5 During this type of training there would be continual adjustment of the work done on volume day so that new PRs can be set continually on the intensity day. Volume work is an absolute necessity for most intermediate trainees but it must be monitored carefully to ensure that priority is always extended to the intensity day. If strength (i.e. force production) is the primary goal, then the metric that is used to measure progress is the heavier loads that are used on the intensity day, not the loads used on the lighter volume days. Too much volume, or too much loading on volume day, can exceed the recuperative capacity of a trainee and stall progress. Volume day performances, such as the trainee’s best 5x5, are important to progress, but it isn’t generally possible to improve those numbers every single week. It will be necessary to make adjustments over time to the either the load on the bar or to make reductions in the set or rep totals in order to manage fatigue. Certainly, if a trainee has competitive aspirations then we must always tweak the program to ensure that the focus remains on the best sets of triples, doubles, and especially singles. No one squats 5x5 in a meet. The volume is simply a tool to drive progress – a means to an end, but not an end in and of itself. Too many trainees get caught up in their focus on volume day and never have the gas in the tank to do any meaningful work on their intensity day. Like any other form of programming, the model we have just discussed will not work forever. Doing 5x5 on Volume Day plus multiple sets of 3, 2, or 1 on Intensity Day is an extremely challenging workload. As trainees grow in strength, so too will they grow in their ability to create stress with less work. On a Volume Day it is very common for trainees to eventually have to shy away from 5x5 and perhaps drop a set or two and do 4x5 or 3x5. Remember, now that the trainee has grown in strength and skill, 3x5 across is a different amount of stress than it was several months or years ago as a novice. Or perhaps trainees will keep a 5x5 protocol on their Volume Day, but now they will do so with perhaps 80-85% of their 5RM rather than 90% of their 5RM. It is also very common for trainees to drop the sets across approach on their Intensity Day. Most new intermediates will start with a rotation of about 2 triples, 3 doubles, and 5 singles. This has been a proven set/rep strategy through the years. However, at some point it is probably beneficial to limit the volume of the Intensity Day to a single set of 3, 2, or 1. In addition, instead of small increments of weight between the trainee’s sets of 3s, 2s, or 1s, it will likely be necessary to create more fluctuation in loading. So instead of just fluctuating workload by 5 or 10 pounds each week, it might be better to fluctuate the loads by 5-10%. A trainee at this level might start a 3 week wave like this: Week Monday Wednesday Friday 1 2 3 405x5x5 410x5x5 415x5x5 325x5x2 330x5x2 335x5x2 Friday: 480x3 505x2 530x1 Additionally, it is not a hard and fast rule that the trainee must always do their Intensity Day work with sets of 3, 2, or 1. After a few 3-week cycles of 3-2-1, the trainee might transition into a several 3 week cycles of 5-3-1 or even 6-4-2 if the trainee wanted to do a little less extremely high intensity work week-in and week-out. The Texas Method can be very flexible and offer the trainee lots and lots of options depending on personal preferences. In conclusion, the lifter and coach should always keep in mind the nature of the Texas Method: above all, it is very stressful. And again, this makes it very useful for the right trainee in the right circumstances. The Texas Method can be used for the long term, but it is not reasonable to expect that you can use Texas Method programming 52 weeks of the year. I think that most serious lifters do best when they plan for competition two times per year, perhaps once in the spring and once in the fall. The Texas Method makes a fantastic protocol to prepare for competition for Powerlifting or Strengthlifting meets. You can set up Texas Method programs for perhaps 12-18 weeks in length (4-6 three week cycles) leading up into the meet. For the rest of the year, it’s probably best to switch to a less stressful Heavy/Light type split routine. Heavy/Light split routines allow the lifter to “let off the gas” a bit between meet prep cycles, and incorporate more assistance work to address potential weak points in their lifts. All serious competitive lifters should look at their training on an annual basis and plan accordingly. If you aren’t willing to put this amount of thought, planning, and effort into your training, then you probably are not a serious competitive lifter. And that’s ok. Some of us just want to get under the bar to maintain our health and fitness, counter the sad effects of the aging process, and on occasion put something cool on YouTube. But understand that the Texas Method is probably not the right solution for you. Serious Lifters Only, Please. Power-Building Optimal Training for Hypertrophy?? This is a really common question and a very common debate amongst trainees, coaches, and trainers and I’m not sure there is a definitive answer to every situation. Unfortunately like so many other debates in the strength & conditioning world the correct answer is almost always prefaced with the frustrating phrase of “well – it depends.” The fact is that there are a lot of big, strong, muscular people on the planet and most of them achieved their results through a variety of different pathways. If there was truly just one particular programming method that worked for size and muscularity then we wouldn’t have a debate, would we? Everybody would be doing the same program and that’d be the end of the story. But for every trainee with a gargantuan set of wheels that squats 3 times per week, I can point to just as many trainees that squat just once per week. Hell, I can point to a lot of people that don’t squat at all and believe that exercises like hack squats and leg presses are superior to squats if we are talking about purely muscle growth and physique development. (That isn’t congruent with my experience, but I’ve known plenty of big bodybuilders who spent very little time in the squat rack). So, two major factors that influence our discussion are the use of drugs (anabolics) and genetics. For the sake of our discussion here, I’m going to throw those two factors out. I have always trained and competed drug-free without the use of steroids or any other PEDs (other than coffee!!!). Likewise, the trainees and athletes that I typically work with through my coaching practice here at the gym as well as my online clients have been drug free. So I can’t speak with any authority whatsoever on the effects of anabolic steroids on a trainee’s programming…other than the fact that they accelerate the results of any type of programming whether it be low frequency or high frequency types of programming. My opinions on drugs have nothing to do with morality. I could care less if people decide to use anabolics as long as they aren’t trying to compete in organizations that have legislated them out of their competitions. Now we’re cheating. But the use of anabolics in non-tested organizations or for their own purposes is fine by me. It’s not a moral judgement – it’s simply just a personal choice that people need to make for themselves. Genetics also blur the picture a little bit because we know that a certain percentage athletes we work with can be classified as “genetic freaks” that respond to just about any type of sensible programming structure. Furthermore, a lot of very gifted athletes respond well to training programs that are just downright terrible, but still seem to get results. In this case, athletes are getting bigger and stronger IN SPITE OF their training programs, not because of them. For our discussion, we will consider my observations to be based on those trainees who are both drug free and genetically average. This is probably where most of my readers fall as well. It’s certainly where most of my clients are. Understanding Your Level of Training Advancement If you are a novice you need frequency. This is why a program like the Starting Strength Novice Linear Progression is so insanely powerful. Squatting 3 times per week for 3 hard and heavy work sets grows the legs, and in fact, the whole body. Pressing and Pulling 3 days per week has the same effect on the rest of the body. Novice trainees, whether the ultimate goal is strength, mass, or both, don’t need anything more specialized than the basic barbell lifts repeated as often as possible with increasing loads at every (or most every) training session. Volume must be set in a way that allows training to occur every 48-72 hours which is why the 5-rep set is preferred for novices. Less reps and the nervous system gets overwhelmed too quickly. Higher reps creates an environment that trainees cannot recover from in a 48-72 hour window and training time is lost because elongated rest periods are required. But can a novice grow bigger and stronger on training a lift (or muscle group) just once per week? Sure. But not as quickly. On the front end of a training career the most powerful stimulus for growth is overload. Simply put – you need to get stronger to get bigger. If you squat 150×5 on day 1, your most powerful mechanism for growth is to build that squat up to 350×5…or 450×5. And there are ways to get there slow, and ways to get there quickly. Let’s choose quickly. And most of us recognize that simple programs that rely on just a few tried and true lifts repeated as often as possible – get us there quickly. So let’s fast forward a bit to a more advanced trainee who has spent a few years driving his basic barbell lifts up as high as he can get them. For arguments sake we’ll say our trainee has achieved a Squat somewhere in the mid 400s, a Deadlift in the mid 500s, a Press in the mid 200s, and a Bench Press in the mid 300s. We’ll say he has achieved these numbers strictly from basic barbell programs like those inside of Practical Programming for Strength Training. His ultimate goal all along has been to build a bigger more muscular physique – maybe he wants to compete in bodybuilding, maybe not. But either way he really wants now to focus on growth and physique development. So the big question is – Does he continue to do what he has been doing? i.e. Does he continue to simply focus on driving up his main lifts in the hopes that more strength will equal more mass? OR Does he need to add any additional hypertrophy specific training to his routine? The answer is YES and YES. More strength will almost always lead to more mass. And the continued pursuit of more plates on the bar creates the right mindset and focus for trainees in the gym. You have to have objective goals in the gym whether you train for physique or for strength. Simply going into the gym to “work a muscle” can create a lot of “drift” in a training plan and trainees often lose focus on consistently practicing the activities that give the most bang for the buck. Consistent progression in strength we know leads to what is commonly referred to as myofibrillar or sarcomeric hypertrophy. In short, this is the growth of the actual contractile units of the muscle cell. Some of have called this type of muscular growth “functional hypertrophy” because it is correlated quite directly with force production. The only problem with strictly focusing on heavy low rep training that leads to myofribrillar hypetrophy is that it isn’t very dramatic after a certain point in time. So, we must recognize that muscle growth and physique development doesn’t just come from gains in strength and a bunch of calories. There is another component of muscular growth known as “sarcoplasmic hypetrophy.” This is the type of muscle growth we often associate with higher volume and higher density training (think higher reps (8-20), more sets, and shortened rest periods) This type of training creates an environment for sarcoplasmic hypertrophy which is more simply thought of as the “swelling” of a muscle cell. The swelling effect typically occurs as a result of an increased capacity of the muscle cell to store metabolic substrates within the cell – namely glycogen and water. Often this type of hypetrophy as referred to as “non-functional” in nature because there is no direct impact on force production save for a maybe a few minor changes in the leverages around a joint. But there is another problem with this type of training that makes it hard to utilize in conjunction with a true strength-building type of program. It’s hard to recover from. i.e. it makes you really really sore for long periods of time. This is why we never use this type of training with novices. It slows down the progression of strength on the main lifts because the recovery period is much longer in between training sessions. So whereas a squat for 3×5 can be performed every 48-72 hours, a squat for 3×10 cannot be. Even though the loads are lighter, the trauma to the tissue is more severe. So What is the Crux of the Problem? The problem is that for optimal gains in hypertrophy the trainee needs both types of training. He needs to train the main lifts heavy with some degree of frequency, but he also needs exposure to higher rep/higher density training. And not just on the main barbell exercises, but also on a myriad of assistance exercises for small muscle groups that are necessary to build a complete physique. So how does a trainee fit all that into a week and still make progress? Some very outdated models of Western Periodization liked to organize a trainees calendar into “blocks” of trainee with a specific focus on one area or another. So for example, a trainee might spend 6-12 weeks training for strength with just heavier low rep training and then transition into another 6-12 week block of just mass which was dedicated to just higher rep/higher density training. The problem with this approach is that time spent in each block means losses from the previous adaptation. 6-12 weeks without training heavy will result in a loss of strength. 6-12 weeks training without a pump (the result of higher rep training) will result in some loss of hypertrophy and loss of muscular endurance. If possible these two types of training need to be trained concurrently, within the same week, for the majority of the year. Many modern bodybuilders (although this is changing) have adopted training protocols where each muscle group is only trained 1x week. But at that single session the target muscle group is ANNIHILATED with a combination of heavy lifts plus lots and lots and lots of high volume assistance work. The muscle group is pounded into submission and then given a complete week of recovery. Great pains were taken to ensure that the muscle group in question was rested completely during the week with no added stress. However the problem with this approach is that for both STRENGTH and MASS a greater frequency is desirable. Muscle Protein Synthesis stops after several days of recovery and by ignoring a muscle group for a week or more, the trainee is missing an opportunity activate this powerful process. In addition, we know that for strength building purposes, there is a greater neural response to training the basic lifts more than 1x/week. Knowing this, many physique athletes have simply adopted a twice per week routine and attempted to beat the hell out of each muscle group 2x/week rather than just once. Problem solved, right? Not really. If you are just training for strength – squatting 2x/week or even 3x/week is fine provided volume is kept reasonable at each session. But what happens when you start adding in the higher volume/higher rep/higher density work needed for optimal growth 2-3 times per week. You can’t recover. You get weaker. Eventually you will overtrain. So What is the Solution? i.e. How do I get it all in without over-training? MY solution is what I call the Direct-Indirect training split. So it all goes into how you set up your training split and how you select your exercises at each training session. If you are careful and deliberate with the organization of your weekly training split and your exercise selection you can adequately cover all your bases. And as a review, the objective of the training program for gains in both strength in muscle mass should meet the following criteria: (1) allow for weekly progression of the basic barbell lifts (2) allow for adequate amounts of higher rep/higher density training for all major muscle groups without negatively impacting strength and recovery So the Direct-Indirect system basically calls for each major muscle group to be hit HARD once per week with a combination of low-rep heavy barbell work for gains in strength and myofibrillar hypertrophy, followed by higher volume rep work and assistance exercises for sarcoplasmic hypertrophy and physique development. About 72-96 hours later, each major muscle group is hit AGAIN, but not nearly as hard. Often the exercise selection you use for another muscle group will indirectly target the muscle that was hit hard earlier in the week. This generally requires a 5-day split with rest days every 2-3 days. For instance the trainee may start the week off with a training session for Chest/Biceps. The trainee will start with something heavy like Flat or Incline Barbell Bench Press for sets of 2-8 reps. Then transition into higher rep exercises using DBs or even machines to round out the workout. Same with biceps. Later in the week the trainee will perform a Shoulder/Tricep workout. However, during the tricep portion of the session, the trainee will intentionally select an exercise like Close Grip Bench Presses, Floor Presses, or Dips that will involve the chest to a large degree. This will be the indirect session for chest. Shoulders and Triceps will have been trained “indirectly” on the trainees Chest Day. Basically all pressing exercises (especially incline work) involve the delts and also the triceps. The biceps will be trained indirectly on the trainees “Back Day” about 72-96 hours after the Chest/Bicep session. Usually no direct curling movements, but exercises like chins, pulldowns, and rows pretty thoroughly involve the biceps. As we just mentioned, “Back” generally receives it’s own dedicated session on a physique program for exercises like chins, rows, pulldowns, shrugs, etc. But the back is hit again during a second session later in the week for Hamstrings, where I always include Deadlifts or some sort of heavy Deadlift variant. Furthermore, lowerbody is trained 2x/week with one session dedicated more towards quads and one more dedicated towards hamstrings and the rest of posterior chain. However, we know that there is plenty of overlap between quads/hamstrings when you perform exercises like Squats and Deadlifts and so this easily satisfies the criteria for a well constructed Direct-Indirect Training Split. Below is how this all looks on paper: Day 1: Chest / Biceps (Indirect work for Delts/Triceps w/ pressing movements) Day 2: Hamstrings, Abs, Calves (Indirect work for Quads & Back via Deadlifts) Day 3: Off Day 4: Shoulders/Triceps (Indirect work for Chest w/ Close grips, floor press, or dips) Day 5: Back/Lats (Indirect work for Biceps) Day 6: Quads, Abs, Calves (Indirect work for Hamstrings via Squats) Day 7: Off This particular routine is not set in stone, but is one that I like most and is the training split of choice for the KSC METHOD for POWERBUILDING available for download on this site. The main takeaway from this article for those of you interested in building size and strength is that you need to find balance in your routine. It’s not just about moving heavy weights, it’s not just about the pump. It’s both. And it’s about trying to find a way to train with optimal frequency. It’s a tough balance and that’s why most don’t achieve it. The Body Builders’ Cure For almost anyone reading this article, they will have, at some point, been bitten by the bodybuilding bug. That does not necessarily mean that one has any aspirations to step onto a competitive stage. Body building in this sense simply denotes that the trainee had some aspiration to build a better physique along with any improvement in their strength and conditioning. For those looking for physique transformation, there are no shortage of “example routines” available in the print media – Flex Magazine, Muscular Development, etc have lured in millions with promises of building “Titanic Triceps”, a “Barndoor Back” or even becoming “Quadzilla” if you do enough drop sets on the Leg Extension machine. I hear there are even some bodybuilding routines available on the Internet? I have to admit, I spent a number of years in my late teens and early twenties combing through the pages of Flex trying to find the perfect routine – the one magical combination of exercises, sets, reps, and scheduling that would explode my physique into comic book proportions. Thanks to some decent genetics and a lot of hard work – I got close. But I could have gotten closer. A single article cannot possibly cover every mistake I made while trying to build my physique in those early years. Perhaps when I’m old and can no longer train I’ll sit back and chronicle them all. However, I think one of the biggest mistakes I ever made was in the organization of my training. Like every physique oriented trainee ever – I focused about 80% of my efforts in the gym on the upper body. Granted the upper body is more complex than the lower body, but for many many years my bias was severe. I few of my favorite bodybuilding oriented splits looked like this: Monday – Chest; Tuesday – Back, Wednesday – Legs, Thursday – Shoulders, Friday – Arms I also spent a lot of time doing this: Monday – Chest, Biceps; Tuesday – Legs, Thursday – Shoulders, Triceps; Friday – Back In retrospect, the second schedule always seemed to work better. The scheduling bias was only part of the big mistake I was making. During my “Leg Days” I considered Squats to be just one exercise as part of a rotation of many many “compound movements” that I rotated through. You have to keep your muscles confused you know? Squats, Front Squats on a Smith Machine, Hack Squats, various forms of Leg Pressing, etc were all staples of the routine – none treated with any more priority than the next. To be honest, at the time I really didn’t care all that much about my legs. Most of my shorts were knee length and I genetically have decent calves. Problem solved, right? Well, what I didn’t understand then was the hormonal impact that lots of heavy leg training has on the ENTIRE body, not just the legs. What I didn’t understand was that had I spent the time developing my squat, and practicing the lift with more frequency, I would have had bigger arms, broader shoulders, and a thicker back. For physique improvement, I’m not opposed to a body-part split. Truth be told, if you want to truly develop your physique to its potential, you have to spend some time working each muscle group thoroughly. Doing just the big compound movements with a program like Starting Strength will build your foundation. But complete development is going to require some more focused physique specific work. Another annoying situation where the “truth” is somewhere in the middle. It ain’t all barbells and it ain’t all pump work. Big chiseled physiques require both. The solution is what I call “The Body Builders Cure” to training organization. The program is designed for those who just LOVE training the upper body like a bodybuilder. The major change is that there is no “leg day.” Instead, “leg day” is scrapped and instead, each workout starts or ends with Squats. So leg day is every day. Using my preferred body part split from above, the routine now looks like this: Monday: Squats + Chest & Biceps Wednesday: Light Squats + Deadlifts & Upper Back Friday: Squats + Shoulders & Triceps A more detailed example plan is below: Monday: Squats 5×5; Bench Press 5×5; DB Incline Press 2×10-12, Crossovers 2×15, BB Curls 4×10-12 Wednesday: Light Squats or Front Squats 5×5; Deadlifts 5RM, 8-12RM; BB Rows 4×10-12, Lat Pulls 3×10-15; DB Shrugs 2×20 Friday: Press 5×5; Seated DB Press 2×10-15; DB Laterals 2×15; Lying Triceps 3×1015; Pressdowns 2×15; Squats 3×10-20 (save for last since you’ll be dead afterward) Is this the most effective routine in the world for maximum strength? Probably not. But I don’t set people’s goals for them. And I know there are a lot of you out there who have physique goals that are just as important to you as your strength goals. This type of routine allows you to do the type of training that makes your time in the gym satisfying and enjoyable. However, if you can start thinking less about “Legs” and more on “Squat training” you’ll be rewarded with a bigger lower and upper body. The hormonal impact of 3 days per week of Squat training is what drives the effectiveness of training programs like Starting Strength, The Texas Method, and Starr’s Heavy-Light-Medium. Squats are unique too in their ability to completely exhaust every fiber of leg muscle that we have. There is no upper body equivalent to the Squat. We truly need at least a handful of exercises for the upper body to completely develop. Leg Extensions, Leg Presses, Hack Squats, etc don’t do anything that Squats don’t. Wanna get bigger? Squat and Squat often. A Simple (and Fun) Method for Mass It’s no secret that 80-90% of the progress we make in the gym comes on steady progression of the core barbell exercises: Squats, Bench Press, Press, and Deadlift. This is true whether we are training for mass & physique, pure strength, or athletic competition. But all of us that train these lifts on a regular basis like to add in a little variety where we can – it makes training fun and we can keep challenging ourselves in different areas over time. By variety, I don’t mean turn your sessions into Junior High P.E. class. But a little bit of variation at the margins of your training routine, if programmed intelligently, can not only make your sessions more fun and more challenging, but you might accidentally build some new muscle in the process! One of the important lessons that Bro-Science has taught us, is that muscle mass is best stimulated by a combination of heavy weight/low reps with complete rest periods, and higher reps/short rest periods with lighter weights. Either stimulus on it’s own is not nearly as effective as when the two methodologies are coupled together in the same workout. I’m sure this is backed up by actual science as well…..however it’s also probably dis-proven by actual science (i.e. you can find a study to prove or disprove just about anything)……which is why sometimes “Bro-Science” is your best reference point! The method that I’m going to describe in this article is based on my experiences training with some legit NPC bodybuilding competitors back in the early 2000s in College Station TX. At the time, the internet wasn’t quite what it is today, and as a consequence more people got big and strong by watching and learning what other big and strong people did, rather than just reading about it online. At the time, it became popular among the group I was training with to perform “challenge sets” at the end of our workouts. I’m not sure who initiated the idea, but for several months we wound up doing a lot of these at the end of just about every workout. I remember we first started doing these during our Back workouts, and we had a pretty simple rotation set up. We would begin with one single heavy exercise for low reps with complete rest in between. For example – weighted pull ups for 5 x 5. Following the pull ups we would do our challenge sets. For a Back workout that began with pull ups (a vertical pull), we would select a rowing exercise (horizontal pull) and combine it with deadlifts for the challenge sets. Challenge sets are based upon the idea of reaching a total number of repetitions (usually 100-200) with just two exercises over the course of 5 sets. Supposing the goal was 100 total repetitions we would aim for 5 sets of 20 reps. If the goal was 150, we would do 5 sets of 30. The first workout I ever participated in using this method utilized deadlifts and heavy full range of motion seated cable rows. After a brief warm up, I did a max rep set of deadlifts (I think I used 385) and did 12 reps. Following the Deadlifts I immediately went and performed 8 seated cable rows – 12 + 8 = 20 total reps. That was set number one. After a 3 minute rest, I went back to the Deadlift and pulled another max rep set, this time I got like 9. Again, I immediately had to proceed to the seated cable row and perform 11 reps in order to achieve the 20 rep goal. That was set 2. This process was completed until all 5 sets were done. I believe I ended that workout with 4 deadlifts on the last set, followed by 16 reps on the seated cable row. It was brutal. The following week, we would switch things around. This time, we might switch the order and begin with a heavy rowing variant (horizontal pull) and use a vertical pull and deadlifts for our challenge sets. The third week, we would generally start with deadlifts for heavy sets, low reps, and full rests and then combine a vertical and horizontal pulling motion. The exercises always changed but we generally had at a Deadlift, a Row, and either Pull Ups or Pulldowns. Some examples look like this (challenge sets in bold): Pull Ups 5 x 5; Deadlifts / Seated Cable Rows 5 x 20 One Arm DB Rows 4 x 8; Pull Ups / Deadlifts 5 x 20 Barbell Rows 4 x 6; Deadlifts / Lat Pulldowns 5 x 20 Deadlifts 3 x 3; Pull Ups / T-Bar Rows 5 x 20 Deadlifts 3 x 3; Barbell Rows / V-Grip Pulldowns 5 x 30 Obviously there are endless combinations to choose from, and the more equipment the gym has, the more you can create fun pairings to use. Eventually, we began to use this same concept with other muscle groups, although for back training it proved to be particularly effective for hypertrophy. Some examples are below: Chest: Combine an Incline Barbell or Dumbbell Press with Dips, after heavy flat bench presses Shoulders: After heavy barbell or dumbbell presses perform challenge sets by doing 8-12 strict lateral raises and finish with 8-12 machine presses Triceps: Begin with an isolation exercise such as lying tricep extensions or cable pressdowns and finish with dips or narrow grip push ups Quads: Begin with 10-20 Leg extensions and combine with 10-20 squats, hack squats, or leg presses. THIS SUCKS!!!!! Often times the weight on a given exercise will need to be adjusted slightly (or significantly) from set to set in order to get the desired effect. There is no reason to do 1 Deadlift and do 19 seated cable rows or 4 Lateral raises and 16 presses. In general, we would try to keep the first exercise above 5 (if it was a compound movement) and above 8 if it was an isolation movement. Rest periods between challenge sets are kept short as the idea is not necessarily to fully recover. This is not a strength protocol. This is a mass protocol which is relation on very high volumes performed in relatively short periods of time. Dragging out the 100 rep routine over the course of an hour is not as effective as condensing the whole thing into 15-20 minutes of focused work. Good luck, and go grow! A Fresh Look at Training Frequency For Power-Building Optimal training frequency is a confusing topic for many. How often should I squat? How often should I deadlift? How often should I bench? The crux of the problem is that there is an absolutely overwhelming amount of anecdotal evidence of great results on both ends of the frequency spectrum. In my own personal experience I’ve seen some very strong power lifters and Olympic weight lifters who squat anywhere from 3-5 times per week. However, I’ve also seen some insanely strong (and large) bodybuilders, power lifters, and “recreational” gym rats who maybe only squat once per week. I’ve seen some brutally strong guys who only squatted heavy once every other week, often alternated on a weekly basis with heavy deadlifts. Several years ago I had breakfast with Kirk Karwoski and we discussed training frequency. He kinda laughed at the idea of squatting more than once per week. Hell, one of the strongest squatters I’ve ever trained with, didn’t squat very often at all. He spent the vast majority of his lower body training doing Hack Squats and Leg Presses. As a bodybuilder, he felt like these exercises did a better job of developing his quads than traditional squats did. He was also a 600+ deadlifter who rarely did deadlifts – instead opting to almost exclusively perform stiff leg deadlifts. Now, I’m not necessarily recommending this as a solution for the masses, but it did work for him. So this kind of leaves us with a problem. The minute that some expert tells you that you have to squat at least 2-3 days per week to make progress, we can point to a guy that only squats heavy every other week and is strong as a bull. The inverse is also true, as soon as an “expert” tells you that you can’t “recover” from squatting multiple times per week, we can find a guy that is brutally strong that squats 3-4 days per week. So what is the right option for you? The long and short of it is that I don’t believe there are any blanket recommendations that can be universally applied to all lifters when it comes to frequency. For novices to strength training, I am certainly an advocate for high frequency training. Obviously the Novice Linear Progression presented in Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training and Practical Programming for Strength Training is my preferred program for most novices. However, once we get into intermediate/advanced territory then the lines start to get more blurry as to what each individual needs in terms of frequency, per session volume, and intensity. For the sake of discussion we are going to assume we are talking about drug free lifting. In my opinion the use of anabolics skews the debate too wildly and drugs can often mask the consequences of sub-optimal or even very bad programming. So my recommendations are going to assume you are training drug free, but looking for progress in both strength and muscle mass. For the drug free strength trainee I am an advocate for each muscle group to be trained every 48-96 hours for optimal growth and strength development. Notice, I didn’t say that you necessarily need to do every lift every 48-96 hours. Some may benefit from training the same lifts more repetitively, some may not. I have clients that respond differently to how frequency is dosed. For instance if we want to train lower body two times per week, does that mean we need to squat two times per week or can we squat once per week and deadlift once per week? It varies from person to person based on their experience, age, absolute strength, and also how much volume/intensity they are using at each individual session. In my opinion, the further along on the spectrum you are in these categories the less need you will have to perform very high volume or very high intensity sessions multiple times per week on the same lift. In general you’ll do better on a system where each lift (or each muscle group) is hit hard every 5-7 days with perhaps a lighter workout for that lift or that muscle group in between. That may mean doing the same lift lighter in between very intensive sessions OR using a lighter variation of the lift in between sessions. It could also mean hitting the muscles used in that lift “indirectly” while training other body parts. So while I believe that each lift / muscle group should be trained every 48-96 hours, I don’t necessarily believe that each lift / muscle group should be annihilated every 48-96 hours. Too frequent high intensity and/or high volume training will lead to overtraining, stagnation, regression, and eventually injury for most lifters. Instead I think the better approach is to hit each muscle group or lift hard about once every 5-7 days with either high intensity, higher volume, or a combination of both. In the interim each lift should be trained lighter, trained with a lighter variation of the lift, or even just ensuring that each muscle group is touched on “indirectly” to speed up recovery, prevent detraining, and spur growth. I design a lot of “power-building” programs for my clients, and these are generally programs that are trying to simultaneously build strength on the primary barbell exercises (Squat, Deadlift, Bench, Overhead Press) but also build muscle mass and improve the lifters physique. That entails a whole lot of work to be done and it must be balanced appropriately across a 7-10 day period for the program to be sustainable in the long term. My experience has been that when you try and cram too much into a 5 day window (Monday – Friday) you’ll wind up overtrained and beat up. So basically for a Power-Building program I’ll set up 5 main workouts and depending on who I’m working with we’ll spread those 5 workouts across a week or ten day period. Generally, we’ll have two heavy lower body days in the rotation. The first lower body day is very squat focused. We do either a lot of volume in the 75-85% range or some very high intensity work in the 90-95% range with some back off sets to follow. We may follow that with a deadlift variation that brings a lot of quad into the movement such as deficit deadlifts or snatch grip deadlifts. Then we may finish with a moderate volume of more bodybuilding or GPP style lower body work depending on the client. The second lower body day in the cycle is more deadlift focused. Generally either regular conventional deadlifts, rack pulls, and then back off work with things like stiff leg deadlifts or RDLs. So this is more of a “posterior chain” focused day. Lots of hamstring and low back stuff. I generally have clients squat again on this day, before or after deadlifts, with either some lighter squats or a variation such as a paused box squat. We’ll finish with lighter high volume posterior chain work with easier exercises like 45 degree back extensions, glute ham raises, reverse hypers, etc. On either day I might allow for them to squeeze in some cosmetic work for the abs and calves if they want. If there is going to be some time elapsed between these sessions, then they have the option to do a third lower body day, but this day might be limited to something like dragging a sled or pushing a prowler. This is a great lower body workout and allows for some active recovery from the more stressful barbell work. Upper body will generally be divided into 2-3 sessions spread across the week. One session is generally Overhead Press-focused and we do either a very high volume or high intensity workout for the Overhead Press (or a combo of both) and then follow that with assistance work for the delts and triceps. In general, one of our tricep exercises will be something like weighted dips, close grip bench press, or floor presses. I make sure to get something in that stimulates the pecs or serves as a light variation of the bench press (whether you think in terms of “muscles” or “movements” doesn’t matter much to me. After all, the muscles are what produce the movements). Later in the week we will hit a heavy Bench Press workout along with a few supplemental exercises (ex: Bench Press, Incline Bench Press, Dips). This will obviously work the chest but also get plenty of indirect stimulation of the delts and triceps. Most of the time, after our chest workout I’ll plug in a few sets for biceps since they are still relatively fresh. For some trainees, I’ll also assign a day strictly relegated to training the back with exercises like chins/pull ups, rows, and shrugs. Or we can just sprinkle these exercises in amongst the other 4 training days if we don’t have the time to add in a 5 th session. We already hit back once during the week with our heavy deadlift session, but a second day focused on chins, rows, shrugs, etc can really kick in some good growth for the lats, traps, and rest of the upper back musculature. All in all, the complete “training week” will look something like this: Monday – Heavy Bench High Volume and/or High Intensity Bench Press work Assistance for Chest & Biceps Indirect work for delts/triceps via bench, incline, dips, etc Tuesday – Heavy Legs Heavy Deadlift focus (conventional or rack pull) Precede or follow with lighter squats or squat variation Assistance work focus on hamstrings, low back Thursday – Heavy Press High Volume and/or High Intensity Press work Assistance focus on delts/triceps Indirect chest / lighter bench press work with close grips, floor press, or dips Friday – Supplemental Back Focus on chins, rows, etc Indirect bicep Saturday – Heavy Legs (Squat focus) High volume and/or high intensity Squat Usually include lighter deadlift variant such as deficit deadlift or snatch grip deadlift, etc. Generally a template like this achieves the goals of increasing strength and muscle mass without leaving the lifter beat up and overtrained with too much exposure to the same series of exercises over and over again during the week. I’ve also used this same template spread out over a 3 day week like this: Monday – Bench + Chest/Biceps Wednesday – Heavy Lower (Deadlift focus + Light Squat) Friday – Press + Delt/Triceps Monday – Supplemental Back Wednesday – Heavy Lower (Squat focus) Friday – Repeat 5 day cycle. If this type of programming sounds like it might be right for you then I’d encourage you to give the KSC Method for Power Building a try. If you want a little bit more hands on coaching and programming on an ongoing basis, then I generally follow this same or similar “power building” template in the Baker Barbell Club (online coaching program). What Rep Range for Hypertrophy? (hint: all of them) What is the meaning of life? How did the universe come into being? And what is the optimal rep range for hypertrophy? These are the great debates that have occupied the brains of modern man for time immemorial. For the young guys reading this that haven’t been immersed in this weight training stuff for very long, it may seem like the debate about rep ranges and what is optimal for strength vs hypertrophy etc is a new thing – let me assure you it is not. It has been going on for decades. To be honest, I’m not sure it’s really an answerable question. The problem is that a “rep range” is not an isolated aspect of your training program or your workout. The rep range can only be analyzed in the context of several other factors, all of which give the repetition it’s actual meaning. A set of 8 is not the same thing as 5 sets of 8. A set of 8 to failure is not the same thing as a set of 8 with 2-3 reps left in the tank. A set of 8 one minute after the last set of 8 is not the same thing as a set of 8 five minutes after the last set of 8. A set of 8 with a strong mind muscle connection is not the same thing as a set of 8 without one. A set of 8 with 545 is not the same thing as a set of 8 with 185. A set of 8 on a Squat is not the same thing as a set of 8 on a Side Delt Raise. So yeah, it makes it hard to come up with answers about what is “optimal” since the discussion is almost entirely context dependent. But we still have to set up a training program and we still have to perform some sets for some reps, so how do we figure that out if our primary objective is to grow bigger and enhance the physique? When it comes to training for hypertrophy (or call it power-building, bodybuilding, etc) then my viewpoint has always been that of take advantage of all potential pathways to growth, rather than trying to isolate the “holy grail” of rep-ranges where muscle magically grows best. So I use the entire spectrum of rep ranges when trying to build muscle, all the way from 2 to 20+. The trick is in applying the rep ranges in the right doses and to the right exercises and to the right body parts. You don’t need to perform heavy doubles every week (nor should you) and you don’t need to do sets of 20 on every exercise either. I personally think that if there is a “sweet spot” for hypertrophy it’s in the 5-8 range, and I don’t think this is a highly controversial opinion. Progressing in this rep range with multiple sets has the right combination of load, and with enough sets, accumulates the right amount of total volume, and even a bit of metabolic stress (i.e. chasing the pump), especially if you play with rest periods. So if I had to pick just one rep range to train in to achieve the goal of strength, muscle mass, and physique development, I guess 5-8 would be it. But fortunately we don’t have to make those silly choices and we can color outside the lines a bit to harness the benefits of training heavier and lighter to really maximize the training effect. That being said, when I design a power-building program for a client, the vast majority of the work we do is in the 5-8 rep range, and in the margins we do some work in the 2-4 rep range in order to train maximal strength, and we do some work in the 10-20 range (sometimes even higher if doing drop sets, rest-pause sets, etc) in order to achieve some metabolic stress (the “pump”) in each muscle group. Now, if we’re going to train in this way, my preference is to set up the weekly training split into 4-5 different workouts that have an intensive focus on one lift and/or one main area of the body. It doesn’t have to be this way, but is just makes training more practical, more focused, and more efficient in my opinion. A typical power-building weekly split is typically organized like this: Monday: Bench Tuesday: Deadlifts Thursday: Overhead Press Friday: Squats And often times I throw in a fifth day of the week for dedicated back work like chins, rows, etc. Once we have the days set up, then I’ll generally select 3 exercises for larger muscle groups (chest, quads, shoulders, hamstrings, lats) and 1-2 exercises for smaller muscle groups (biceps, triceps, abs, calves, traps, rear delts, etc), and then start assigning each exercise it’s rep range for the day. So on the Bench Day we might go: Flat Bench Press Incline Bench Press Dips or Cable Flys Deadlift day might also be called our “hamstring/posterior chain day” and I’d set up a workout like this: Deadlifts RDLs Leg Curls Squat Day might be a quad emphasis day and I’d set up a workout like this: Squats Hack Squats or Leg Press Leg Extensions Press Day might be: Overhead Barbell Press Seated Dumbbell Press Side Delt Raises The first movement of each day is our strength focused lift and 99.9% of the time should be a multi-joint barbell exercise that uses maximal loading. For this first exercise I tend to use straight sets / sets across with rest times being whatever is needed to complete the prescribed volume using perfect form, and generally avoiding sets to failure so that the focus can be on adding weight (or reps) week to week and/or cycle to cycle. I generally go with my standard 3 week mini cycle of rotating out 8s, 5s, and 2s although other strategies and programming methods could also be used (i.e. anything reasonable that works for you). Week 1: 3 x 8 Week 2: 3 x 5 Week 3: 3 x 2 Week 4: Repeat and add weight to each rep range if possible. So here, 2 of the 3 weeks of the mini cycle are in that “sweet spot” of 5-8 reps per set and every 3rd week we jack up the weight for doubles across. Handling the heavier weights every 3 weeks or so is a good way to keep strength progressing without burning yourself out with maximal loading in the +90% of 1RM range week in and week out. I sometimes switch out the first exercise with a close variant (deficit deadlift, front squat, incline bench, etc), but most of the time, it works best to just stick with the “big 4” each week and try to improve your performance on the 8s, 5s, or 2s. The second lift each day is an exercise that I feel best maximizes both loading as well as “isolation” of a particular muscle group. So a Hack Squat is a good example of this for the Quads. An RDL is good for the hamstring. An Incline Bench Press is good for the chest, but so is a Dumbbell Bench Press. So for the second exercise of the day we want something that enables you to move some weight, but I also want you to be able to really feel the muscle you are trying to work. So at some level, this is very individualized, based on the mindmuscle connection you can establish with this exercise. Some will work better for some than others. I almost always use Descending Sets for this exercise. That is to say, I will assign 2-3 work sets, but each work set generally decreases in weight and increases in reps (although the reps don’t always increase if fatigue is high enough from the previous sets). However, these are not Drop Sets. Descending Sets generally use a longer rest time between sets so that “mostly complete” recovery can take place. I usually cap the descending sets around 3 minutes of rest between sets. Drop Sets usually have 30 seconds or less rest between efforts. I will more or less match the first work set of the second exercise to whatever rep range we used for the first exercise of the day. This kind of preserves a “theme” to the workout as either heavier or lighter and allows you to build strength on your secondary exercises as well. The second and third work sets are dropped by 5-20% each and reps are increased so that the final workset is almost always reaching at or near failure in the 8-12 range. Depending on the exercise we are at or near failure on every set for this exercise. Here is an example using the Bench Press and Incline Bench Press: Week 1 Flat Bench Press 3 x 8 (sets across, full rest between sets) Incline Bench Press 1 x 8-10 (drop 5%) 1 x 8-12 (drop another 5%) 1 x 8-12 (note: at the higher rep ranges, I use small drops of about 5% and often times, the reps don’t change much as fatigue accumulates) Week 2 Flat Bench Press 3 x 5 (sets across, full rest between sets) Incline Bench Press 1 x 5-6 (drop 10%) 1 x 8-10 (drop another 5-10%) 1 x 8-12 Week 3 Flat Bench Press 3 x 2 (sets across, full rest between sets) Incline Bench Press 1 x 3-5 (drop 10%) 1 x 6-8 (drop another 10-20%) 1 x 8-12 So now the meat and potatoes of the workout is done and we move onto a third movement that is generally purely an isolation movement that trains in a much higher rep range with very short rest intervals or no rest intervals at all. This shouldn’t take long, but the density should be high i.e. a lot of reps in a very short period of time. There are lots of ways to do this, and it varies from one exercise / bodypart to the next and so this has to be done largely by feel. This means that you need to select exercises / rep ranges / techniques that give you the most massive pump you can possibly achieve. Weight doesn’t matter much here, although it should be bumped up over time as you can. Drop sets, rest-pause sets, sets for time, or even just 1-2 very high rep straight sets all work here. For the Quads the 3-week mini-cycle might go like this: Week 1 Squat 3 x 8 Hack Squat 1 x 8-10 (3 plates per side) 1 x 10-12 (2 plates per side) 1 x 12-15 (1 plate per side) Leg Extensions 1 x 15 (to failure) then a double drop set of 10 reps per set. Week 2 Squat 3 x 5 Hack Squat 1 x 6-8 (4 plates per side) 1 x 8-10 (3 plates per side) 1 x 10-12 (2 plates per side) Leg Extensions 1 x 20 (to failure) then 3-4 rest pause sets of 5 reps each with 20-30 seconds between each set Week 3 Squat 3 x 2 Hack Squat 1 x 4-6 (5 plates per side) 1 x 6-8 (4 plates per side) 1 x 8-10 (3 plates per side) Leg Press 1 x 50 reps with as few breaks between reps as possible. For the smaller muscle groups, we’ll generally just select 1 or 2 exercises and use the midrep range sets and maybe some density sets. Biceps might be: Incline DB Curls 6-8 x 40s, 8-10 x 35s, 10-12 x 30s (descending sets) Barbell Curls 1 x 15 to failure + 2-3 rest-pause sets of 5 (metabolic stressor) Triceps might be: Weighted Dips 3 x 6-8 (straight sets) Cable Pressdowns 3 x 10-15 + 1 drop set of 15 at the end (straight sets + metabolic stress) A question I get asked a lot by my trainees is “Can I do all this with just a single exercise, and just vary the rep ranges within the workout?” In other words, can I do this?: Squat 3 x 5 Squat 1 x 6-8, 1 x 8-10, 1 x 10-12 (descending sets) Squat 1 x 15-20 Yes, but it has it’s drawbacks. In my opinion, this much volume on a single exercise week after week after week has diminishing returns in terms of both size and strength. I feel that rotating through the second and third tier movements leads to less stagnation, less over use type injury, and better growth. I don’t have anything to prove this one way or the other, other than many years of programming this type of training for clients and observing the results. The other downside to running this type of scheme with a single barbell exercise is that it just wrecks your body (especially if you try it with squats and deadlifts). It’s hard to recover from physically. Especially when you try and apply the metabolic stressor type tactics to barbell exercises. You might get away with this on occasion, but week in and week out it is going to eat you alive. You can get the same (and actually better results) with this type of training by coupling your heavy barbell exercises with dumbbells, machines, cables, and bodyweight exercises fr the second and third tier movements. Don’t get me wrong, the method I’m advocating for is hard too, and not without recovery difficulties, but I have found that using a wider variety of exercises allows you train harder at each session without wrecking yourself. I strongly believe that it’s important to learn how to match the rep scheme / tactic to the right exercises. Go heavy with barbells. Pump up with dumbbells, machines, cables, and bodyweight. The other side is the mental aspect. When doing this type of training, I like my trainees to stay fresh and engaged mentally. This keeps training motivation higher, and when motivation is higher, effort is higher. Beating yourself to death with the same 3-4 exercises week in and week out is not a good long term strategy for growth and physique development in my opinion. When training for growth and physique development I believe that variety in exercise selection is not only helpful but necessary, because I also believe that effort must be high and that a good portion of your training volume should include sets at or near failure if you want to grow. You can’t do this on the same movement every week! You don’t need 42 different movements per body part to choose from, but you probably need a staple crop of maybe 4-6 movements per body part you rotate through every few weeks over the course of the year. The Benefits of a Dedicated Back Day (why & how) Introduction No one disputes the benefits of having a big strong back – whether it’s for power lifting or body building (the competitive or non-competitive versions of either) the upper and lower back are exceedingly important. For squatting, it’s nice to have a wide and thick shelf for the bar to rest upon as we’re pushing through a heavy weight, and provide a stabilizing force for the thoracic spine. I think we’ve all seen lifters get doubled over by a heavy weight, something that probably should be corrected with better mechanics, but perhaps could have been avoided with a stronger, bigger upper back. For Benching & Pressing, the lats play a roll in supporting the lifter (especially at the bottom of the movements), they help with a tight and powerful “arch” in the bench, and they provide a nice buoyant shelf for the triceps to rest on at the bottom of the press. And in my opinion, the lats and upper back muscles play a supportive roll in helping the lifter lower a heavy load under control and maintain a steady vertical bar path. I’ve noticed this quite a bit simply by the soreness pattern that presents in the lats the day or two following a heavy high volume bench or pressing session. It’s not severe, but it’s there, particularly after doing something like multiple heavy sets of singles or doubles across, where the eccentric tends to be a bit slower than with lighter weights for more reps. You can also test this out by trying to bench or press heavy the day after doing a bunch of chins and/or rows. You’ll find you have a little less pop out of the bottom of the movement and a lot less control of the bar path. A big strong back is obviously most helpful in the Deadlift, and as novices and early intermediates, trainees, may not need much more than Deadlifts and perhaps a few sets of chins to build a decent starting foundation of lower and upper back musculature. However, as the trainee advances through his lifting evolution, he needs to give a bit more attention to developing his back in order to maximize the contribution to all the major lifts. And if he or she is a physique oriented lifter (competitive or non-competitive bodybuilding) then certainly the back must receive additional stimulus than what is provided simply through dead lifting. Certainly all the great bodybuilders of the modern era (Haney, Yates, & Coleman most notably) had an upper back musculature that simply blew the competition off the stage. The Problem…….. When we’re trying to become notably stronger or bigger than we are right now, it requires a lot of work. If we’re power lifting (or bodybuilding), we need to spend a lot of time doing Squats, Deadlifts, and the derivatives of these movements. Most lifters probably need to be hitting each of those lifts or their variants 2 days per week, some people may even need more frequency than that. We also need to train the Bench Press and probably a few assistance exercises there as well including things like Presses, Inclines, Dips, DB Pressing variants, pin presses, direct tricep work, etc. This type of work also generally consumes 2 and maybe even 3 days per week for many. So the problem is that time and energy are often in short supply for important exercises like pull-ups and various forms of rows. These movements are extremely important for developing and strengthening the back, but they too are energy expensive, and they are quite capable of being trained with very heavy loads. However, most people wind up haphazardly slapping a few sets of chins or light rows onto the end of an upper body session or deadlift session and never really commit the time and energy to performing these exercises with the loads and volumes that are necessary for optimal back development. The Solution….. If you are primarily a physique oriented athlete, I’d say that this is a must, and perhaps you are already doing so. If you are a strength oriented athlete (power lifter, strength lifter) I’d say this is something you should strongly consider trying. What I’ve been recommending to many of my clients over the years is that they implement a dedicated session every week to training the back – separate and apart from their Deadlift training (which we’ll keep coupled with squats on lower body training days) and separate and apart from their Bench and Press training and all the constituent assistance exercises for those lifts. This often winds up being a Saturday session if the lifter is training on the popular 4-Day Upper-Lower Split (example): Monday: Heavy Bench + Light/Volume Press + Assistance (Dips, Triceps, etc) Tuesday: Heavy Deadlift + Light/Volume Squat + Lower Assistance (low back, Prowler, etc) Wednesday: Off Thursday: Heavy Press + Light/Volume Bench + Assistance Friday: Heavy Squat + Light Deadlift (SLDL, RDL, etc) Saturday: Back Day Sunday: Off When setting things up like this, I’m usually pretty intentional to put the lower body day that is Heavy Deadlift focused on Tuesday and the Heavy Squat focused Day on Friday. First, you don’t want to be trying to do a bunch of heavy barbell rows (which will be a staple of the back day) the day after doing a bunch of heavy deadlifts. Second, spreading the Heavy Deadlift Day and the Back Day more evenly through the week, in essence gives you two dedicated back training sessions. And if you are trying to prioritize this body part, it’s a good idea to hit it hard every 2-3 days. Setting Up the Back Day Routines….. I actually have three different back routines that I really really enjoy doing and seem to get the best feedback and results from clients when prescribed. The idea of the Back Day is to get progressively stronger on a handful of staple exercises (perhaps 6-10 movements), overload the back with a lot of volume, and catch a massive pump in the back at each session. This is how you will grow. If you cannot feel your back and lats completely blown up at the end of each session, I’ll bet you dollars to donuts you won’t see much change in your physique. The Back (a large collection of multiple muscle groups) responds best to a wider assortment of exercises than simpler muscle groups like say, the Quads, which probably don’t need 6-10 exercises to stimulate growth. The Bro-Science part of this is that the back seems to respond better when these exercises are mixed and matched a bit rather than performing the same combination of exercises in the same order at every session. So I’m giving you three routines to rotate through each week. At the end of each session, I leave it up to the trainee to perform perhaps 2 additional sets of exercises for the Rear Delts, Traps, and Biceps. You don’t have to do all 3 at every session, you could rotate through these as well based on time, energy, and need. Sets and reps may vary a little bit from person to person, day to day. I’ll give you my recommendations, but feel free to add, subtract or adjust based on feel. Try and keep the exercises and exercise order. I set each of these routines at 15 total sets, which in combination with your Deadlift and Deadlift Variants each week will put many people around the 18-25 set marker for the back each week. It might take this much to elicit a dramatic growth response if your back is really lagging. Routine #1 Barbell Rows (pulled from the floor or from the “hang”) 6 x 6-8. Go heavy but stay strict. Seated Cable Rows or Old School T-Bar Rows 3 x 8-12 (choose one) Pulldowns (wide overhand or reverse grip) 4 x 10-12 One Arm DB Rows 2 x 12 (strict form, deep stretch) Routine #2 Pull Ups or Chin Ups (weighted or unweighted) 5 x 5-8 Barbell Rows 4 x 8-12 Chest Supported Machine or T-Bar Rows 3 x 10-12 Pull Downs (use opposite grip of how you did exercise one) 3 x 10-12 Routine #3** Pull Ups (weighted or unweighted) 5 x 5-8 Rack Pulls (knee height) 1 x 6-8, 1 x 10-15 Rack Barbell Rows (from same pins as rack pulls) 5 x 10-12 V-Grip Lat Pulldowns 3 x 10-12 **On the Deadlift session that follows the Rack Pull session (2-3 days later) you may have to lighten things up a bit to accommodate for fatigue, or make that session another Squat focused lower body day. Rack Pulls should be done for one all out heavy set of 6-8 reps and then back off 10-20% for another all out set of 10-15 reps. Rack Barbell Rows are done with a fairly upright torso angle and pulling the bar low into the stomach (like a Yates Row). VGrip Pulldowns are pulled into the upper abs, not the top of the chest. In combo with the Rack Pulls, these will blow up the lower lats. Tips…… Keep track of loads and aim to get stronger on each and every exercise over time, but do not become centrally focused on load only. Think like a bodybuilder when doing these routines and try and establish a mind-muscle connection with the lats. These are “exercises” and not “lifts”. If you are just heaving weight around, you won’t get the same response as you will from feeling the lats stretch and contract on every rep and walking away from each set with a massive pump. Adjust the loads during each workout to make sure you are using proper form and feeling the lats work. Keep rest down to 2-3 minutes between sets. Adjust weight as needed to accommodate this. Descending sets can be your friend on back training sessions. I suggest using straps on most of these exercises to take the grip out of the equation, minimize forearm fatigue/involvement and keep the feel of the exercise on the lats. Try implementing this into your routine over the next 12-weeks and see if your back does not respond in a big way. I guarantee you it will. Cycling Bench & Incline on 8/5/2 (Power-Building Programming) Those of you who are following my KSC Method for Power-Building Program are familiar with two recommendations I make in the introduction of that program. One recommendation is to follow the 8-5-2 progression for your main exercise each day. That means setting up your primary barbell exercises for each day in a 3 week cycle that rotates between 3 sets of 8, 3 sets of 5, and 3 sets of 2. This is probably my most tried and true intermediate progression. It’s simple. It works. And it’s sustainable for long periods of time without over-reaching, constant resetting, etc. Another recommendation I make is to periodically rotate the main exercise you perform each week at each workout. This gives you an opportunity to train some important lifts when you are fresh with maximal loads. While I don’t believe in the concept of “muscle confusion” in the way that the Weider Magazines describe it, I do believe in a little variety in training, especially at the intermediate level. Some sensible variations that still serve the ultimate goal of the program are a good idea. This can help you break through plateaus, or probably more accurately stated, it can help you avoid them, by forcing your body to get stronger on lifts that contribute to the performance of the parent exercise. Getting stronger on more than just 3-4 exercises is going to make you stronger in the long run. Ed Coan followed a very basic routine of mostly Squats, Bench Presses, and Deadlifts, but he was also a huge advocate of things like High Bar Squats, Paused Squats, Incline Press, Close Grip Bench Press, Stiff Leg Deadlifts, and Barbell Rows. Ed treated the training of these lifts as seriously as he did the Big 3. Most of the time, these were second or third in his workouts, but occasionally he would prioritize a few of these variations and try to really drive up his strength on these lifts by training them fresh. I’m a big advocate of rotating in the Incline Press with the Bench Press as a staple chest exercise. This is true whether you are training purely for strength and especially if you are training for physique. For physique oriented training, Inclines are a must. In the system outlined in the KSC Method for Power-Building, we hit our chest 2x/week. The first session of the week is our “direct” session where we use the heaviest weights, the highest volumes, and the most exercises. Later in the week we hit the chest “indirectly”, usually with just a single movement – my preference being Dips for this second lower volume, lower intensity session. Let’s assume session one is on Monday and we’ll focus on Flat and Incline variations (although you could also perform dips here also) and session two is on Thursday – hitting Dips on our dedicated Shoulder/Tricep workout to ensure we get a little chest stimulation twice per week. So we train Chest twice per week but we don’t kill the chest twice per week. We kill it 1x/week and just “touch it” later in the week. This is my preference when training for mass and physique. Here is a sample week: Monday Bench Press 3 x 8 / 3 x 5 / 3 x 2 (rotate scheme weekly) Incline Bench Press 3 x 8-10 DB Bench Press 3 x 8-10 Biceps – 6 sets Thursday Shoulders – 6-9 sets Dips – 3 x 10+ Triceps Ext 3 x 10 Using this basic template you can work in your Incline Press prioritization in one of two ways – (1) every other cycle (2) every other week. Here is how Monday would look training every other cycle: Week 1 o Bench Press 3 x 8 o Incline Press 3 x 8-10 o DB Bench Press 3 x 8-10 o Thursday – Dips 3 x 8-10 Week 2 o Bench Press 3 x 5 o Incline Press 3 x 8-10 o DB Bench Press 3 x 8-10 o Thursday – Dips 3 x 8-10 Week 3 o Bench Press 3 x 2 o Incline Press 3 x 8-10 o DB Bench Press 3 x 8-10 o Thursday – Dips 3 x 8-10 Week 4 o Incline Bench Press 3 x 8 o Incline DB Press 3 x 8-10 o Dips 3 x 8-10 o Thursday – Close Grip Bench 3 x 8-10 Week 5 o Incline Bench Press 3 x 5 o Incline DB Press 3 x 8-10 o Dips 3 x 8-10 o Thursday – Close Grip Bench 3 x 8-10 Week 6 o Incline Bench Press 3 x 2 o Incline DB Press 3 x 8-10 o Dips 3 x 8-10 o Thursday – Close Grip Bench 3 x 8-10 Week 7 – Repeat 6 week cycle Here is how training would look switching priority every other week: Week 1 Bench Press 3 x 8 Incline Press 3 x 8-10 DB Bench Press 3 x 8-10 Thursday – Dips 3 x 8-10 Week 2 Incline Bench Press 3 x 5 Incline DB Press 3 x 8-10 Dips 3 x 8-10 Thursday – Close Grip Bench 3 x 8-10 Week 3 Bench Press 3 x 2 Incline Press 3 x 8-10 DB Bench Press 3 x 8-10 Thursday – Dips 3 x 8-10 Week 4 Incline Bench Press 3 x 8 Incline DB Press 3 x 8-10 Dips 3 x 8-10 Thursday – Close Grip Bench 3 x 8-10 Week 5 Bench Press 3 x 5 Incline Press 3 x 8-10 DB Bench Press 3 x 8-10 Thursday – Dips 3 x 8-10 Week 6 Incline Bench Press 3 x 2 Incline DB Press 3 x 8-10 Dips 3 x 8-10 Thursday – Close Grip Bench 3 x 8-10 With the second option, I really like keeping the 3 week cycles of 8-5-2 even when the main exercise is rotated. I’ve tried it before with 2 weeks of 8s, 2 weeks of 5s, 2 weeks of 2s, and I don’t think it worked as well. However, there is plenty of wiggle room with how you arrange the other movements. For Power-Building, I like the 8-10 range for the secondary movements. I’ve also had good success with clients who don’t have good dumbbells to work with, doing something like this: Week 1 Bench 3 x 8 / 3 x 5 / 3 x 2 Incline 3 x 8-10 Dips 3 x 8-10 Thursday – Dips 3 x 8-10 Week 2 Incline 3 x 8 / 3 x 5 / 3 x 2 Bench Press 3 x 8-10 Dips 3 x 8-10 Thursday – Dips 3 x 8-10 Sometimes, simple is better, and you really can’t go wrong with performing Dips multiple times per week when mass and physique is part of the goal. And if you have never Benched second, after Inclines, try it. Your chest will thank you / hate you for it. Deadlifts on Back or Leg Day? + Power-building Split Advice I get asked a lot about how to set up a proper power-building type training split. One that has training for increased strength on the big lifts as its foundation, but also some dedicated time for training towards increased muscle mass and a better physique. Contrary to what you might have been told, simply “getting stronger” doesn’t necessarily lead to huge gains in muscle mass or a better physique after the novice stage. While strength is the foundation for both, these are specific adaptations that must be trained for….specifically. Of course we all know that the Deadlift is a great builder of both strength and size. But it can sometimes present some programming complexity because it’s very systemically stressful and it taxes so much muscle mass at once. In a Power-building split it’s hard to find a place to slot in the deadlift because it tends to take away from everything else, especially when trained heavy with higher volumes. Do you combine with Squats on a Leg Day? Or Do you combine with Pull Ups and Rows on a Back Day? Either way is tough. Deadlifting heavy for high volume before or after heavy squats generally means that one or the other has to be trained sub-maximally. If you’re an intermediate or advanced lifter, especially if you are over 30, it’s hard to train both maximally in the same session. Deadlifts work well on a Back Day, but they know doubt take away from the energy you can commit to lots of chins, pull ups, and rows. And those exercises are helpful if you are trying to power-build correctly. A big back needs that type of work in addition to the heavy deads. My solution is to pair Deadlifts with neither. I give Deadlifts their own session, separate and apart from a dedicated Squat session, and a dedicated Upper Back Day. In a Power-Building split I have my clients train 5 days per week. Two of those training days are Lower Body / Leg Days. One of those two sessions is a Squat-focused session that primarily focuses on Squats and Squat variations and then assistance exercises that focus on development of the quads. Then we finish with some abs and calves. So that workout might be: Squats or Front Squats 4 x 4 Hack Squats 4 x 8 Leg Extensions 4 x 12-20 Standing Calf Raise 4 x 20 Decline Sit Ups 4 x 15 At another point during the week we’d have a second Lower Body session that is Deadlift focused, and we’d follow that up with assistance exercises for the hamstrings and lower back, plus more abs and calves. So that might be: Deadlifts 4 x 4 Low Bar Box Squat or Goodmornings 4 x 8 Glute Ham Raise or Leg Curl 4 x 12-20 Seated Calf Raise 4 x 20 Hanging Leg Raise 4 x 15 So the Deadlift obviously works the back, the traps, and the legs, with an emphasis on the posterior chain (hams & low back). But for a power-building split we need more back work than just deadlifts once per week. So we have a separate day each week to focus on more “bodybuilding style” back exercises to focus on hypertrophy and detail. Our back session is usually something like this: Wide Grip Pull Ups 4 x 8 V-grip Pulldowns 4 x 12 Barbell Rows 4 x 8 Seated Cable Rows 4 x 12 Barbell Shrugs 4 x 15-20 The workouts are placed into the week like this to ensure maximal recovery, maximal frequency, and optimal spacing of the workouts during the week. Tuesday: Deadlifts + Ham/Low Back Assistance Friday: Upper Back Hypertrophy (pull up, rows, etc) Saturday: Squats + Quad Assistance This optimizes what I call the “direct/indirect” method of training frequency for hypertrophy. I believe best long term gains come from when muscle is trained about 2x/week, but with varying levels of stress. Once per week, each muscle group is hit HARD with very moderately high intensity and very high volume, and later in the week it is stimulated again, although often indirectly with less volume and less direct attention. So Deadlifts hit the Hamstrings and Low Back super hard on Tuesday, but also provide some work for the upper back and quads, although those muscles won’t be absolutely hammered today like the hams and low back will be. 2 Days later the back is hit again, this time with a very high volume of direct exercises for the traps and lats (chins, rows, shrugs, etc). 3 days after deadlifts the Quads are hit super hard with Squats and Squat variants. This will, of course, provide a lot of hamstring work from squatting, but not nearly the attention and volume they received on Tuesday. If you are trying to train for strength and physique, it can be done, but you have to be smart about how you lay out your training week. 4 Day Split for Hypertrophy For those of you who have already picked up my power building program, you already know the basic principles I adhere too when designing a hypertrophy focused training program. One of those principles is the Direct / Indirect principle for designing your training week. Basically what this means is that I like to have one day per week where my trainee really really hammers a particular muscle group, and then later in the week we hit that muscle “indirectly” or just with overall less stress. For instance, you might hit the chest really hard on Monday with Bench Presses, Incline Presses, and Cable Flys, and then later in the week you hit the chest again when training your triceps with an exercise such as Dips or Close Grip Benches. So the chest gets hit 2x/week, but once with lots of volume and the second time we kinda just touch on it and then move on. The biggest complaint with my KSC Method for Power-Building program is that it’s a 5-day split……and many of you just don’t have 5 days to train. Often times, your training split is a trade off with your schedule. Some guys do better to train more often, but with shorter training sessions, and others do better to train less frequently but with longer workouts. So go with whatever schedule is going to help you stay consistent with your program. If you can train 4 days per week you can still put together a very similar program to my 5day Power Building program. It may even work better for many of you that do better with more days of recovery in your week. In the 5-day program I have 2 full dedicated lower body days….one is more quad focused, and the other is more focused on hamstrings, glutes, and low back. I also have a dedicated day in there for Back Training (lats, traps, rear delts, etc). So this is the day we do lots of pull ups, pulldowns, rows, shrugs, facepulls, etc. For the 4-day program, I usually just split up the hamstring focused lower body day and the upper back day and spread load some of that work load across the week. The basic skeleton of the program starts pretty standard: Monday: Bench Tuesday: Squat Thursday: Overhead Press Friday: Deadlift Now I’ll walk you through how I organize the assistance template, capping each day at 6 total exercises for an average of 3 work sets per exercise, a pretty good workload for most. For the lower body work, I focus the direct quad work on the Squat Day since we’re already warmed up. If we start with heavier squats then I like the second exercise to be something like leg presses, hack squats, paused high bar squats, etc for work in the 10-ish rep range. Then we’ll usually finish with some metabolic stress high density work using the leg extension machine for 3 sets in the 15-ish range, using short rests, or even no rests using drop sets. Later in the week we’ll hit the quads again with some light Squats and Deadlifts, but it’s relatively low stress compared to Tuesday. For the Hamstrings, I’ll usually put a knee flexion exercise (Leg Curls or Glute Ham Raises) on Tuesday after the quad work and then something like RDLs for higher reps or Weighted 45 Degree Back Extensions on Friday after Deadlifts. So now our lower body training is like this: Tuesday: Squat Leg Press / Hack Squat / High Bar Paused Squat / etc Leg Extensions Leg Curls or Glute Ham Raise Abs Calves Friday: Light Squat Deadlifts RDLs or Weighted Back Extensions For the Back Work, I generally split that up between Monday and Friday. On Friday’s is where I stick the heavy rowing variations that produce fatigue in the low back. If we are gonna work the back on Monday, which is the day before squats, don’t be an idiot and do something like heavy barbell or t-bar rows which are gonna fatigue the lower back the day before heavy squats. So on Monday, I usually program in Chins or Pull Ups, and also some Rear Delt work. On Friday, I plug in some heavier rows, shrugs, and maybe another pulldown or row variation for higher reps. So now our skeleton program looks like this with the Back Work included: Monday: Bench Press Chins or Pull Ups Rear Delt Raises or Face Pulls Friday: Light Squat Deadlifts Barbell or T-Bar Rows Lat Pulldowns DB Shrugs 45 Degree Back Extensions The rest of the program generally looks the same as the 5-day split. On Monday, after we Bench, we’ll throw in two more exercises for the chest, usually a barbell or dumbbell incline press and then either a fly variation or dips. We’ll also hit the biceps Monday. Thursday would be exactly like the 5-day split – a focus on Overhead Pressing, delts, and triceps. The full program outline looks like this (as an EXAMPLE…not prescriptive for any one person) Monday Bench Press DB or BB Incline Press Chins or Pull Ups Dips Rear Delt Raises Bicep Curls Tuesday Squat Leg Press or Hack Squat Leg Extension Lying Leg Curl Calves Abs Thursday Overhead Press Dumbbell Press Side Delt Raise Close Grip Bench Lying Tricep Extension Cable Pressdown Friday Light Squat Deadlifts Barbell Row Lat Pulldown Shrugs 45 Degree Back Extension OR Light Squat Deadlifts RDL Dumbbell Row Lat Pulldown Shrugs If you are interested in the full 5-Day power building program, you can pick that up here: KSC Method for Power Building. Frequency & The Power-Building Split For those of you that follow my Power Building routine, or at least my writings on power building type training, you know that I’ve come to favor a 5-day training routine for my clients. Of course you can split things up into a 3-day or a 4-day routine (and those work well for many), but I feel like to really get the best combination of size, strength, and physique development, the 5-day split is optimal. In my standard program there are 2 lower body focused days and 3 upper body focused days. The problem? A lot of my clients don’t have 5-days a week to train. And I understand, as I often don’t either. Several years ago, I decided to test out extending my “training week” beyond the traditional Monday-Sunday 7 day week, which is a purely societal construct anyways. So instead of trying to cram in 5 training days into a 7-day week, I simply fit my preferred split into a schedule that worked for me. What I started doing was this: Mon: Bench + Chest/Bicep Weds: Deadlift + Hamstrings, Calves Fri: Press + Delts, Triceps Mon: Upper Back, Traps Weds: Squats + Quads, Calves Fri: Repeat Schedule On certain weeks I would train on either Saturday or Sunday if I wanted to. And that shortened the split down by a few days, but most of the time I simply adhered to the schedule above. What did I find? I found that I had outstanding results. I got stronger and I grew like a weed. And almost as important, I felt GREAT going into each training session – physically and mentally. Always refreshed and always hungry to train my ass off on that days lift / muscle group. I rarely missed my target numbers on my big lifts and made progress on all my assistance exercises as well. This schedule has now become my “default” training program for most of the year. As I worked out the kinks with the split I started implementing it with clients and I found similar success with many of them. Not only were my clients growing and getting stronger – they were having fun in the gym, they never felt beat up, and this led them to train harder and harder and get even better results. One thing I’ve done with this split is make sure that I “sneak” some added frequency in there in order to make sure that each muscle group (not necessarily each lift) is actually being stimulated more often than it would appear at first glance. This is less important for me, as I respond well to lower frequency, but very important for some of my clients. The heavy Bench Press is trained on the chest/bicep day , usually first in the workout, followed by Incline Pressing and usually Dips to finish. Often times we have clients start with Inclines and do Bench Press second. So that takes care of the Chest, but also serves as a pretty good second day stimulus for the Triceps and also the Delts (especially if Inclines get hit first). And then later in the week when we directly train the triceps, I do lots of extension type work, but also almost always incorporate Dips or Close Grip Benching, both of which hit the Chest pretty hard, serving as it’s second day stimulus. So now we have Chest, Delts, and Triceps each getting hit twice during the “week”, each one once really hard, and each once more indirectly. On the Deadlift Day, we obviously do Deadlifts (hamstrings, quads, and back) but I often precede or follow that up with Box Squatting. So while this is a hamstring dominant leg workout, the quads get hammered pretty hard too. And then we have a Quad dominant workout later in the week which usually has plenty of squatting and leg pressing, both of which hit the hamstrings for a second time in the week. The Back and Traps are hit on the Deadlift Day, but both are hit later in the week too with a more direct, higher volume session that involves lots of things like Chins, Rows, Shrugs, etc. And in turn the high volume Back workout serves as the indirect stimulus for the Biceps which are usually trained after the Chest workout. The body part split gets a lot of hate now days for not delivering enough training frequency, but that is really a myth. Sure if you try to go to some weird extreme and work each muscle group totally in isolation, then yes, frequency is low and results will be terrible. But nobody does that. Does anyone “do quads” by simply doing leg extensions? Does anyone “do chest” by strictly hitting the pec-deck? The reality is that most people hit multiple muscle groups every time they train, even if the focus of the day happens to be fairly narrow. It’s a straw man argument. The truth is that most body part splits can deliver adequate frequency as long as you remember, it’s all about exercise selection!!!! Being intentional about what exercises you choose ensures that muscle groups are stimulated more often, and this can be the case whether you want to perform your 5 workouts inside of a traditional 7 day week, or if you want to extend things out like I do. I can hear many of you already up in arms about the lack of Squat, Bench, and Deadlift frequency on a plan like this. And yes, in some cases it may be less than once per week for the actual competitive movement. But remember, if the goal is added muscle mass and physique development – you don’t have to build your training around the Squat, Bench, and Deadlift. If you are a power lifter, then you do. In bodybuilding, no one cares about your total. So it’s a question of priority. In fact, I have several more advanced clients who do very little Squatting, Benching, and Deadlifting because mass and physique are the primary goals and we have found that those exercises are not the best for them at this stage of their training. But that’s another article for another day. Pumpin’ Ain’t Easy Sorry about the cheesy subject line. I just couldn't help it, given the topic of this email. If you are following my Power Building program, you know that I recommend that the final exercise for each muscle group be something that chases a massive pump versus chasing a massive weight. In the past few years we have started to call this Metabolic Stress. That is generally something that is done with higher rep ranges, short rest times between sets (or no rest), and is generally an isolation exercise that is not limited by peripheral fatigue. In other words, Bench Presses for sets of 15 on 30 sec rest are probably a bad idea because the triceps are likely to gas out way before the pecs do. But a Chest Fly for sets of 10-15 on 30-60 sec rest is a good idea because the only limiting factor is the musculature of the chest. When you are training for maximal muscle size, it's not a bad idea to look at attacking the major muscle groups with varying methodologies in order to get the most out of your training. I like to set physique oriented clients up to work in 3 different "pathways" for the big muscle groups. First, we want progressive overload in the compound movements that allow for the greatest loads to be lifted, across the longest effective range of motion. These are typically your basic barbell exercises. These sets are 1-3 reps shy of failure for a few sets across in the 4-8 rep range. The goal is adding weight to the bar every week or every couple of weeks Second...I look for a movement that can cause some pretty good muscle damage via a combination of (1) load (2) a long eccentric phase (3) a deep loaded stretch position at the bottom end of the range of motion (4) highish reps taken to or very near failure So if exercise number one was a Squat for a sets 5 reps......exercise number two might be a Hack Squat for sets of 10. If exercise number one was a Bench press for sets of 5 reps, exercise number two might be a Dumbbell Press for sets of 10-12 Third is our "pump" exercise. Or where we chase Metabolic Stress on the muscle group. Leg Extensions, Cable Flys, Lateral Raises, etc. Isolation movements that can be trained with sets of 15-20 reps per set. 30-60 second rests between sets. You can also do things like Myo-Reps here. Basically a 15-20 rep 'activation set" to failure followed by multiple low rep sets of maybe 3-6 on 10-15 second rests until we hit a desired rep total or the reps just drop off too much. Here is are a couple of sample workouts for various body parts: Quads: Back Squat 3 x 5 (same weight each set, 1-2 reps in reserve each set, 3-5 min rest between sets) Hack Squat 2 x 10-12 (take first set to within 1 rep of failure 2 minute rest between sets, drop weight 25% for second set) Leg Extension - 3 x 10-15 (60 sec rest between sets. Drop weight each set to maintain volume) Chest: Incline Bench Press 3 x 5 (same weight each set, 1-2 reps in reserve each set, 3-5 min rest) DB Bench Press 3 x 8 - 12 (take all sets to failure, 2-3 min rest between sets, drop weight 5-10 lbs per set) Cable Fly - 30 reps. (Take first set to failure around 15 reps. Myo-Reps up to 30 on 10-20 sec rests) Conjugate Program A Simple & Complete Guide to Conjugate / Westside Training The Conjugate Method is a term and methodology made most popular by Louie Simmons, owner of the Westside Barbell Club and the creator of what has become known as the “Westside” method of training. Since Louie started publishing his articles on his methodologies in Power Lifting USA back in the 1990’s, the methods grew wildly in popularity mainly for two reasons – (1) it was/is totally different from the standard power lifting programs up until that time, and (2) the methods worked for a lot of lifters. Since then, Louie’s methods (as evidenced by his own writings) have evolved and morphed over and over again through the years and this has created confusion as to what exactly the Westside method is and isn’t. Combine that with the fact that 100s of power lifting and sport coaches have borrowed from, modified, and bastardized the Westside method over the years to blend with other programming models, even more confusion was created. And lastly, especially in recent years, with the popularity and rise of Raw power lifting, the Westside method has come under severe criticism for only being applicable to Multi-Ply power lifters who compete in federations with very lax standards on things such as squat depth. Much of this criticism is fair and warranted. Some is not. I am a firm believer in the utility of the methods, not only for the raw power lifter, but perhaps even more so for the recreational strength athlete who needs a system that is malleable, flexible, easily adjustable, variable, fun, and not predicated on long drawn out progressive training cycles. More on this later… But first let’s look at some terminology associated with this program. The Westside Method This is Louie’s mixture of the Max Effort Method, the Dynamic Effort Method, and the Repetition Effort Method, blended with a healthy dose of GPP/conditioning work to get the Westside Method. I would say that if you are not training at Westside Barbell, then you aren’t technically doing the Westside Method, you are doing a version of the Method. The system is a concurrent system. This is a fancy way of saying that multiple athletic qualities are simultaneously trained at once, instead of in separate blocks over the course of a training cycle. Some programs might spend 4 weeks training for hypertrophy, 4 weeks training for strength, and then maybe 2 weeks training power production, then tapering into a meet. In the Concurrent System, every week work is done on all relevant qualities – absolute strength, power, and hypertrophy. This is maintained virtually year round. So every week you will train the Max Effort Method on a Squat or Deadlift variation and a Bench Press variation for absolute strength. This generally involves working up to a 1-rep max or at least some sets at or above 90% of 1RM. In other words you go super heavy twice per week, once for upper body, once for lower. Every week you will also train Power with the Dynamic Effort Method. Usually all 3 power lifts are trained in this fashion, with lots of sets, low reps (1-3 usually), and lighter weights with maximal volitional bar speed. Every week you will do “special exercises” i.e. assistance work for the squat, bench, and deadlift. This basically means lots of exercises for the pecs, shoulders, triceps, lats, lower back, hamstrings, and quads. This is where you work in the typical bodybuilding rep range of 8-15 reps and try and build as much muscle mass as possible and address weak points. Every week you will also train your conditioning with activities like Sled Dragging and Prowler Pushing in order to maintain the work capacity to push long and hard in the gym. Louie is a big, big believer in training volume. And the more work you can do on your Dynamic Effort Training and your special exercises the stronger you will become. But you have to be in shape enough to train. The Conjugate Method So the Conjugate Method is not actually the same thing as the Westside Method, although the two terms have become so closely linked as to be almost interchangeable in the dialogue. But technically, the Conjugate Method is simply a PIECE of the overall Westside system. Conjugate training is simply a way of saying that you constantly rotate your exercises in and out of the program. This comes into play on the Max Effort Day and with the Special Exercises / Assistance Work. Typically we will perform the competition versions of our Squat, Bench, and Deadlift on the Dynamic Effort Day. This gives us tons of volume and lots of practice on those lifts. But you cannot train the same lifts maximally week in and week out. You either have to wave the loads around OR if you want to practice lifting heavy every single week, you have to wave the exercises around. The latter is conjugate training. Basically a different max effort lift every week. And perhaps you come back to that lift every 6 weeks or so and try to beat your previous best performance. Accessory movements are treated the same way. You do a movement for 1-2 weeks at a time, push it as hard as you can, and then swap it out for a different but similar movement, and come back to it in a few weeks and try to break a record on it. Below is an example 6 week cycle of the Conjugate Method at work for a Max Effort Bench Press Day: Week 1: Competition Bench Press – 1RM + 2-3 @ 90%. Incline DB Bench Press 5 x 8-12. Barbell Rows 5 x 8-12. Lying Tricep Extensions (ez curl bar) 5 x 10-15 Week 2: Incline Bench Press – 1RM + 2-3 @ 90%. Flat DB Bench Press 5 x 8-12. T-Bar Rows 5 x 8-12. Overhead Tricep Extensions (ez curl bar) 5 x 10-15 Week 3: Close Grip Bench Press – 1RM + 2-3 @ 90%. Incline DB Bench Press 5 x 8-12. One Arm DB Rows 5 x 8. Cable Tricep Pressdowns 5 x 10-15 Week 4: Bench Press w/ Bands – 1RM + 2-3 @ 90%. Close Grip Bench Press 5 x 8. Seated Cable Row (narrow grip) 5 x 10-15. Lying Tricep Extensions w/ Dumbbells 5 x 10-15 Week 5: Swiss Bar Bench Press – 1RM + 2-3 @ 90%. Flat DB Bench Press 5 x 8-12. Hammer Strength Row 5 x 8-12. Overhead Tricep Extension w/ Cable 5 x 10-15 Week 6: Floor Press – 1RM + 2-3 @ 90%. Incline Barbell Press 5 x 8. Seated Cable Row (wide grip) 5 x 8-12. Dips 3 x failure. So in the above example our sample template is a (1) max effort bench variation (2) supplemental chest exercise (3) a row (4) a tricep extension. I like the use of a template like this (you can create your own template based on need and preferences) and then just plug in new exercises week. Record Keeping…….. It is absolutely vital that you keep records of the max effort and assistance exercises you are performing. Constantly aim to break new records and set new personal bests. This doesn’t mean you actually will break a record every time you train, but try to. On the max effort day, you need to be aiming to break your old 1-rep maxes each time you cycle back to that exercise. On the special exercises you need to try and be setting new bests in the form of increased load, adding reps, or adding sets. So if your previous best DB Bench Press was 3 x 10 x 80, you need to try and do 3 x 10 x 85, 3 x 12 x 80, or 4 x 10 x 80. Any of those would constitute a PR. The Ideal Training Split ……. Usually I set this up for my clients as a 3-5 day per week training program with 4 days being the average. The original training split set up by Louie was like this: Monday – Max Effort Squat / Deadlift Wednesday – Max Effort Bench Press Friday – Dynamic Effort Squat / Deadlift Sat or Sun – Dynamic Effort Bench Press I often set it up like this: Monday – Max Effort Bench Press Tuesday – Max Effort Squat / Deadlift Thursday – Dynamic Effort Bench Press Friday – Dynamic Effort Squat / Deadlift Either way, I recommend scheduling a day of REST after the max effort squat / deadlift day. The 5-day split is basically identical to the above except we add a 5th day that is a body building style “Back & Biceps Day.” This can be nice because back accessory work like heavy rows and chins are actually pretty damn taxing and they have a way of getting half assed at the end of the other sessions. The back day allows a lifter more time and energy to train the back movements harder and more time in the other workouts to focus on other assistance movements. Monday – Max Effort Bench Press + Assistance for Chest & Triceps Tuesday – Max Effort Squat / Deadlift + Assistance for Hamstrings & Low Back Thursday – Dynamic Effort Bench Press + Assistance for Delts & Triceps Friday – Dynamic Effort Squat / Deadlift + Assistance for Quads and Abs Saturday – Back & Bicep Day (about 15-25 total sets) In the 3-day per week schedule we simply take the 4-day program and spread it out over a 3-day week. This works great for lifters who struggle with recovery or who can only commit to 3-days per week of training. Monday – Max Effort Bench Press Wednesday – Max Effort Squat / Deadlift Friday – Dynamic Effort Bench Press Monday – Dynamic Effort Squat / Deadlift Wednesday – Repeat Cycle This is exactly how we program this method in the Baker Barbell Club. Now, let’s get into a breakdown of each training day. Max Effort Bench Press Day I like to set up the Max Effort Bench Press Day in cycles of 6 weeks in length and I’ll show you how and why. Week 1 is going to be the “competition” version of your Bench Press. i.e. your normal Bench Press. This is important from a “testing” stand point – i.e. you need to be able to gauge if your program is working, but also as a way to set up the percentages for your Dynamic Effort training day. So however you normally Bench Press, use that technique today. In Week 2 use an Incline Bench Press. Standard would be about a 45 degree bench with a normal bench grip, but in subsequent cycles you can modify things like angle of the bench and grip width for even more variety in programming. In Week 3 use a Close Grip Bench Press. You can do a normal touch n go, use a pause, or even press off the pins in following cycles. In Week 4 use accommodating resistance – i.e use bands or chains and use your normal bench press technique. In Week 5 use a specialty barbell. Use a cambered bar, a swiss bar, a fat bar, etc. In Week 6 use a partial range of motion. Use a floor press, a 1 or 2 board press, or a pin press. After the 6 week cycle go back through and repeat everything and try and break new records. So the base cycle is 6 weeks, but if you modified each exercise each time through the cycle you could actually come up with a pretty good 12-24 week cycle using the basic template I provided above. Beginners won’t need that much variety, but more advanced athletes may. For example: Week 1: Bench Press Week 2: 45 degree Incline Bench Press Week 3: Close Grip Bench Week 4: Bench w/ Mini Bands Week 5: Swiss Bar Bench Press (narrow grip) Week 6: Floor Press Week 7: Bench Press (test) Week 8: 60 degree Incline Bench Press Week 9: Close Grip Bench Press (from dead stop off the pins) Week 10: Bench w/ Monster Mini-Bands Week 11: 3 inch Camber Bar Bench Press Week 12: 1-Board Press You could go on and on forever, but having a loose template in place helps give some organization to your training. If you don’t have all the gadgets (bands, chains, specialty bars, etc), no problem. Set up your own cycle using different grip widths, pin positions, bench angles, etc and you can come up with a long list of options for max effort bench cycles. For the max effort movement you are going to work up to a max effort single for the day, aiming for a personal best when possible. I always recommend aiming for a conservative PR first, and then go by feel after that. So if your previous best on the Close Grip Bench Press was 275 lbs x 1, then today, make your target 280 lbs x 1. If you nail 280 x 1 as a fast and smooth rep, try one more set. Maybe anywhere from 285-295 lbs x 1. If 280 lbs was a grind it out type of single, you are done for the day. The idea is to hit a top single for the day but avoid a bunch of missed reps. After the top single for the day, deload the barbell to 90% and hit a top set of 2-3 reps. Then move onto the special exercises / assistance. After the Max Effort exercise, I recommend you do work for the Chest, using a high volume of sets in the 6-12 rep range. My favorites are Dumbbell Pressing at a flat, incline, or decline angle. Dips are also good. You can also take an exercise that is normally on your max effort menu and use it today for higher reps. Inclines are good, so are many specialty bar exercises. Just make sure you hit a bunch of volume and leave with a huge pump in the chest. Rotate this exercise out every week or at least every 2-3 weeks. Try not to go “stale” on a movement. The minute you regress or don’t make progress, swap it out. Come back to it in a few weeks. After that, hit 2-3 more exercises for the lats, triceps, delts, etc. Dynamic Effort Bench Press Day People get super confused here because the recommended percentages are literally all over the place in the “official” Westside literature. Let me attempt to simplify. For a raw lifter using straight weight (no bands or chains), use 60-70% of 1-rep max in a 3-week wave and perform 8-12 sets of 3 reps. For example: Week 1: 12 x 3 x 60% Week 2: 10 x 3 x 65% Week 3: 8 x 3 x 70% Week 4: Repeat cycle. Rest times should be about 30-90 seconds in length. We WANT a high density of training here, but we also want bar speed. So take as little time as possible between sets, BUT rest long enough so that fatigue doesn’t slow down your bar speed. I recommend you pause each rep on the chest and then EXPLODE up as fast as possible on the concentric. Use your competition Bench Press (i.e. normal) set up and technique, but just move every rep explosively. When you come back through the cycle, you don’t need to increase the weight. Repeat the same weights again, but try and move the loads FASTER and/or decrease rest time from the previous cycle. Every time you hit a new Bench Press PR (every 6 weeks or so) then you can adjust the weight on the bar to reflect your new max. If you want to use bands or chains for Dynamic Effort work, lower the bar weight down to 50-60% of 1RM and then add the bands or chains. Test a set out. If the reps move slow, then reduce weight even further and perhaps do a wave at 45-55% of 1RM. But use light band tensions only – Mini Bands or Monster Mini-Bands are enough. After the Dynamic Effort Benching, I usually move my lifter onto heavy direct overhead pressing work. Standing Barbell Presses or Seated DB Presses are my go to’s. Again, we want a high volume of pressing and then we’re gonna follow that with more work for the delts, lats, and triceps, as needed. Max Effort Squat / Deadlift Day A 6-week cycle of max effort movements works here as well, although you can of course spread it out over a longer cycle length. And I think for most advanced lifters a 12 week cycle is probably better. In the example below I’m using a 12-week Template, but you can obviously pare this down to something more basic In order to keep it simple, just alternate each week between a Squat variation and a Deadlift variation each week. Do not use a TWO max effort movements in the same day, every week. In Week 1 max out your competition squat for testing purposes and to set up your percentages for your dynamic effort squat day. However you regularly squat is how you will squat today. In Week 2 max out your competition Deadlift. If you compete with a conventional pull, do that. If you compete sumo, do that. In Week 3 do a Front Squat. I like a “lighter” movement here because of the stress generated by the max effort squat and deadlift in previous weeks. I also like front squats for assistance throughout the program so having a rough 1RM on paper is useful for estimating loading. In Week 4 do a Deadlift with the opposite stance of what you used in week 2. If you pull sumo, then do a conventional Deadlift today. If you pull conventional, do a medium stance sumo pull today. In Week 5 do a Squat to Pins or a Box. Either way, get down at or below parallel and pause for a good 2-3 count. In Week 6 perform a partial Deadlift. So this is a Rack Pull or Block Pull. Usually this is something just below the knees. In Week 7 perform a Squat with a Specialty Bar. This is usually a Safety Squat Bar or a Cambered Bar. You can do this to a box or as a “free” squat. In Week 8 perform a Snatch Grip Deadlift. Grip somewhere between the rings and the collars depending on height. In Week 9 perform a Squat with accommodating resistance. You can go with or without a box, but add chains or bands to the bar. In Week 10 perform Deficit Deadlifts. Stand on a platform about 2 inches in height and perform regular conventional deadlifts. In Week 11 perform Squats with a Pause. Don’t use a box or pins. Just pause the weight for a good 2-3 count at the bottom of your regular squat position and come back up. In Week 12 perform Deadlifts with accommodating resistance. Add bands or chains and deadlift with your competition stance. You can alter this menu of course, but the order of the movements is intentional to build towards better testing in Week 1 and Week 2, so try and stick with this as close as possible if you have the right equipment in place. Usually on the max effort day we’re going to work the hamstrings and lower back really hard using the conjugate system. After the main movement pick a supplemental movement like RDLs, SLDLs, Goodmornings, or Weighted 45 degree hyper extensions. Or you can pick an exercise from the max effort menu. Rack Pulls are one of my favorites for supplemental work. Hit some good volume here without killing yourself. 2-5 sets in the 6-10 range. Then finish with a few other lighter movements such as unweighted 45 degree extensions, leg curls, glute ham raises, or reverse hypers for sets in the 10-20 range. Dynamic Effort Squat / Deadlift Day Like the Bench Day, there is a lot of confusion how to use this day for the raw lifter. A lot of the official literature on Westside has a whole lot of information about boxes and accommodating resistance like bands and chains here and it can read very confusing. A lot of this stuff is written with a lifter competing in multi-ply power lifting in mind. So we don’t need above parallel box squats with tons and tons of band tension. Remember that today is serving as the main VOLUME STIMULUS and the main chance to PRACTICE your COMPETITION lifts. The max effort exercises and the assistance exercises are changing often and will help to build strength and muscle mass, but we need to make sure we stay TRAINED on the lifts we actually compete with or test with. So I recommend staying with a form and technique here that is very close to, if not exactly how you compete. I think just a regular Paused Squat (without the box) with maximal acceleration on the concentric is best here. IF you prefer to do your dynamic squats with the box, that is fine, but be wary of the fact that losing the “feel” for the bottom of the squat can be a very real thing with a raw lifter. If you choose to box squat, stay tight at the bottom and make sure the box is at or below parallel. Using your competition squat as a guide, the raw lifter can set up a 3-week wave with 6070% of 1RM for about 16-24 total reps per workout. Rest times are generally 45-90 seconds Week 1: 12 x 2 x 60% Week 2: 10 x 2 x 65% Week 3: 8 x 2 x 70% The use of doubles is simply convention here, because it basically assures there is no drop in bar speed within a set. But there is no reason why you couldn’t do triples for a bit of added volume, and some lifters even do well using a conventional 5 x 5 workout with these same percentages. This would yield a similar protocol to what Fred Hatfield advocated for several decades ago with his Compensatory Acceleration Training (CAT) which is similar to the Dynamic Effort Method. After the speed squats, we’ll move onto Dynamic Effort Deadlifts, which, by convention yet again, is often programmed for with a high set count of singles with one set performed approximately every 30 seconds with maximal bar speed. However, there is no reason why you can’t pull for 2-3 reps per set provided your bar speed stays elevated. I often program the Deadlifts at about half the volume of the Squats. So usually something like this: Week 1: 6 x 2 x 60% Week 2: 10 x 1 x 65% Week 3: 8 x 1 x 70% If you are going to add bands or chains to the Dynamic Effort Squats or Deadlifts then I’d lower the percentages down by 10% as we did with the bench. So now loads are 50-60% of 1RM plus band tension. Light band tension is fine here. We aren’t trying to mirror the strength curve of a squat suit so super heavy band tension is not needed or productive. Light band tension can be very effective. Once you get warmed up on the Squats you ought to be able to complete ALL the squat and deadlift volume in around 30 minutes or so. It’s a very fast and efficient workout and why you need to be in shape enough to train this way. The density of work and bar speed need to stay elevated for this to work, otherwise you are just lifting light weights slowly which does not work. After the Dynamic Effort Squats and Deadlifts I like some dedicated leg work – especially for the Quads. I actually really like things like Leg Presses, Hack Squats, and Leg Extensions here because you can hit the quads hard with some quality volume, but save the lower back from further abuse. Single leg work like lunges and step ups are also good today. If you aren’t into the body building type of leg work then a great follow up to the Dynamic Effort Day is just to go push the Prowler until your quads want to explode. This is a great option for guys who want to “train like an athlete.” explosively. Deadlift explosively. Push the prowler. Done. Squat Sample Full Week of Training (4-Day Split) Monday – Max Effort Bench Press Day Close Grip Bench Press – work up to 1-rep max for the day. Back off 10% and perform 1 set of 2-3 reps. Incline DB Bench Press 5 x 8-12 Chest Supported T-Bar Row 5 x 8-12 Lying Tricep Extension 5 x 10-15 Side Delt Raise 3 x 20 Tuesday – Max Effort Squat / Deadlift Day Front Squat – work up to 1-rep max for the day. Back off 10% and perform 1 set of 2-3 reps. Stiff Leg Deadlift – perform 3 sets of 5 reps 45 Degree Back Extensions – 5 x 10 Lying Leg Curl – 3 x 10 Thursday – Dynamic Effort Bench Press Day Bench Press 12 x 3 x 60% Standing Barbell Press 4 x 8 Chin Ups – 50 total reps Dips – 3 x failure Hammer Curls 3 x 10 Friday – Dynamic Effort Squat / Deadlift Day Squat 12 x 2 x 60% Deadlift 6 x 2 x 60% Leg Press 5 x 10 Leg Extensions 3 x 15 Weighted Decline Sit Ups 3 x 10 Again, just a sample here but it shows how things might get organized. Summary……..and why this works for average Joe’s. One of the things that I like best about the Westside method is that it’s a bit random. You can certainly structure things into a long range multi-week / multi-month plan, but you don’t have to. As a regular guy with a job and family life it can be difficult to stick to a long drawn out multi-week / multi-month training plan which is how many “conventional” plans are drawn up. Interruptions happen and missing a few sessions or especially an entire week(s) can completely blow up your training program. With this style of training it doesn’t matter. The whole thing is almost completely autoregulated based on your state of preparedness TODAY. You just go in and max out today and do whatever you can do. You go in today and take out a light to medium weight and squat it FAST. It doesn’t have to be exact. Something that moves fast with a little effort. Then pick 2-4 assistance exercises and chase a massive pump with each exercise. Done. That’s it. Very little planning is involved and you can basically train HARD every time you are in the gym. This method is excellent for guys who (1) love to train hard (2) have trouble with highly structured programs. This program is also FUN. If you like a little of everything and a lot of variety this program has it. Want to train heavy? Max Effort day Want to train explosively? Dynamic Effort Day Want to do a little body building? Do as much as you can handle Programming with the Conjugate Method (my favorite features!) There are a lot of things to like about the Conjugate Method. Over the last year or so I’ve really fallen in love with the method (again) for use with my clients. After many years of experimentation I feel like I’ve finally got a “formula” down for how to best apply the methodology with the general demographic that I work with. For those that might be unfamiliar with the methodology, a quick review: the conjugate method is often used interchangeably with what is known as the “Westside Method” – derived from the methods used by Louie Simmons at his gym Westside Barbell in Columbus Ohio. You can busy yourself for hours, days, weeks reading and watching material straight from Louie and Westside if you want to get into the finer details of his practice. The conjugate method is really just a piece of the total Westside method if we want to break down all the semantics. The total Westside Method is a combination of The Max Effort Method, the Dynamic Effort Method, and the Repetition Effort Method. In short, this means every week trainees will train with maximal weights to train absolute strength, medium weights moved with maximal speed to train power, and light weights moved for high repetitions in order to build muscle mass. Typically the week is organized like this: Monday – Max Effort Squat or Deadlift Variation + 2-4 lower body assistance exercises (repetition method) Wednesday – Max Effort Bench Press Variation + 2-4 upper body assistance exercises (repetition method) Friday – Dynamic Effort Squat & Deadlift + 2-4 lower body assistance exercises (repetition method) Saturday – Dynamic Effort Bench Press + 2-4 upper body assistance exercises (repetition method) The Conjugate Method generally applies to the max effort training days. This means that in general we are doing a different variation of the Squat, Bench or Deadlift every single week. And every single week that movement is trained maximally i.e. we are working up to a 1-rep max in whatever variation we choose that week. The goal is to avoid misses if possible, but end with a heavy all out single that causes us to strain extremely hard under very heavy weight. This is why choosing different exercise every week is not just something we do for fun and variety but because it is a necessity. You cannot max out on the same movement multiple weeks in a row. You will burn out, regress, and even get injured. However, if there is variety in exercise selection you can actually train maximally (100% of 1RM) week in and week out without burnout and with less chance of injury. One of the criticisms of this type of training is that it is too non-specific to power lifting (where it is most commonly employed). In other words if we are doing Box Squats, Rack Pulls, Front Squats, Deficit Deadlifts, Goodmornings, Safety Bar Squats, Snatch Grip Deadlifts, etc we aren’t getting the necessary technical practice and repetition with the movements that we are actually trying to compete with. This is a misunderstanding of the system. On Max Effort Day, the SPECIFICITY we are looking to achieve is NOT technical proficiency…..it’s the STRAIN we are after. Which makes it incredibly specific to power lifting. So again….the movement that you choose for your max effort day is actually a bit less important than the fact that you strain hard under a very heavy load (relative to the movement you choose). This might be 350 on a Front Squat one week and 650 on a Rack Pull the next week. Done right, the absolute loads will oscillate and vary every week which is why you can make the system work. Straining under a very heavy load regularly not only prepares you physically for heavy 1-rep max attempts on the competitive version of the Squat, Bench, and Deadlift but also mentally and emotionally. When you are used to max weights every week you aren’t freaked out when it comes time to test or compete. The lift-specific volume and the technical practice of the lifts generally comes on Dynamic Effort Day. In contrast to the 90-100% loads we use on Max Effort Day, on the Dynamic Effort Day we’ll use loads generally between 60-80% for lots of sets (I usually use about 10) but low reps (1-3). I’ve found that I’ve been getting good results for clients with about 30 reps for the Bench (10 sets of 3 reps) and about 30 reps combined for Squat / Deads (10 sets of 2 for Squat, and 10 x 1 (or 5 x 2) for Deads). The emphasis on this day is bar speed, technical proficiency, and density (i.e. a lot of work done in short periods of time using 30-120 rest periods between sets depending on load for the day). I’ve been running a 5-week wave for my clients starting at 60% and going up in 5% increments each week up to 80% and then running the “wave” again starting back at 60%. The goal is not necessarily to add weight every time (although we bump up weights when we set new maxes) but to move the same loads faster and faster and perhaps with less and less rest between sets. So back to the title of the article…..What do I love BEST about this methodology?? Aside from the fact that the method is extremely effective and fun….I really love the fact that there is no structured long term planning involved. This factors in PERFECTLY into the lives of many of my clients – all of which have jobs, families, travel schedules, that often interfere with their ability to complete a highly structured long term 8-16 week training program. It also accounts for the fact that clients may or may not always be at the same state of readiness on a given training day. Bad sleep the night before, stress at work, etc and the planned Sets x Reps x Load that they need to complete for the day simply doesn’t happen. The conjugate system accounts for all of this. Many of the programs that I sell on my site and many of the programs I write for my clients are structured in a way that a certain amount and type of work must be done between Week 1 and Week X in order to produce a peak at a meet or testing day in Week Y. This works on a correctly designed program. But I often get emails and texts from clients asking what to do during the program because they have to miss 1-2 weeks for business travel or because they contracted the Flu, etc. Or they are shift workers with a fucked up sleep schedule etc. This is problematic to a highly structured time sensitive program. Or perhaps you trained consistently for 12-weeks hitting all your prescribed numbers but then on your scheduled testing day you come down with a sinus infection or the A/C goes out at your house. Being sick or distracted and your testing day goes all to hell. That really sucks as it’s hard to hold that peak for very long. The conjugate system doesn’t require you to focus on much more than THIS week. On Max Effort Day you pick an exercise and go balls out on it. Work up to a 1-rep max. If your schedule and consistency has been off for the last month you may or may not set a PR today. And that’s okay. You aren’t necessarily expected to hit a PR at every max effort session. They will manifest themselves throughout the year but it’s rare (i.e. it never happens) that you will set PRs 52 weeks out of the year. What matters is that you strain against a heavy load. Pick a handful of complimentary assistance exercises that support that lift and crank out a bunch of volume in the 8-15 rep range. On the Dynamic Effort Day later in the week your Percentages of 1RM need not be highly precise. Estimate a weight that is between say 60-70% of what you think your 1-rep max might be at that time and move it for 2-3 reps as fast as you can. If it’s slow…..peel some weight off until you are hitting some reps with speed. Again the goal today is a moderate weight moved FAST, not necessarily an EXACT weight. Once you get a few weeks of this under your belt your capacity to move heavier and heavier loads comes back rather quickly. In my online barbell club, where I run a conjugate program for my clients, new members often ask “What week should I start the conjugate program?” My answer is usually – this week. You can hop into the program at any time. There isn’t a definitive stop and start point necessarily. And if you miss a week or two for whatever reason, you just hop back into the programming. No going back to Day 1, Week 1 or any of that shit that drives clients and coaches nuts. If you come into the gym that day tired, hungover, a little sick or whatever it’s fine. Go the heaviest or fastest that you can on that day. If you come into the gym rested, full, pissed off and ready to tear the head off a Rhino, then crush some new PRs with the heaviest weights you can handle. Or put 70% on the bar and try to explode it through the ceiling. To me this is the ultimate system for auto-regulation. If you like auto-regulation (you must auto-regulate as an advanced lifter), but dislike RPE based systems this is a great alternative. This isn’t me bashing RPE. This is just another alternative for those who dislike using that type of system. So are there downsides to this system? Yes. Mainly when lifters first start this type of training there is going to be a learning curve. Using new max effort exercises every week is going to be unfamiliar. When you start doing things like Front Squats or Snatch Grip Deads, etc you might just feel a bit awkward and uneasy about taking them out for heavy singles and you may not feel like you are getting much out of them, especially since we don’t do them every week. But as you give the system time you will get better and better at each of these movements, which makes performing them more and more effective. For this reason I suggest two things: 1) Don’t set up a rotation of exercises that has 986 different options to choose from. Limit your selection to maybe 10-12 at most. (2) don’t use the variations just for max effort. You might only max out the front squat once every 12 weeks or so, but you can include the movement for volume perhaps as often as every other week as a supplemental movement. This will give you the chance to practice the movement and build up strength more frequently making your max out days more productive. Here is a sample 12 week rotation for the Bench Press: 1. Competition Bench Press 2. Standing Overhead Press 3. Close Grip Bench Press 4. Incline Bench Press (30-45 degree) 5. Floor Press 6. Bench Press with Light Band Tension 7. Seated Overhead Press off Pins 8. Specialty Bar Bench Press 9. Incline Bench Press (45-60 degree) 10. Rack Bench Press or Spoto Press 11. Bench Press with Heavy Band Tension 12. Long Paused Bench Press (3-5 sec pause) Of course you can mix and match your own favorite exercises and just using different grips etc you can create lots of variations without a lot of specialized equipment. Here is a sample 12 week rotation for the Squat / Deadlift 1. Competition Squat 2. Competition Deadlift 3. Front Squat 4. Sumo Deadlift 5. High Bar Squat 6. Rack Pull 7. Box Squat 8. Deficit Deadlift 9. Squat with Light Band Tension 10. Snatch Grip Deadlifts 11. Safety Bar Squat 12. Deadlift with Light Band Tension One little trick to use on max effort lower body days with a program like this is to perform the next week’s max effort movement as the second exercise of the day for something moderate like 4 x 4 in order to get accustomed to the movement before hitting it for a max the next week. For instance (reference the order above): Week 2: Deadlift 1RM + Front Squat 4 x 4 Week 3: Front Squat 1RM + Sumo Deads 4 x 4 Week 4: Sumo Deads 1RM + High Bar Squat 4 x 4 Week 5: High Bar Squat 1RM + Rack Pull 4 x 4 etc, etc Using this system my clients are getting stronger faster than ever before. And even better, they are training with motivation, having fun, and not stressing about missed weeks, bad workouts, etc, etc. The PRs are rolling in the insane regularity from members of my private coaching group. Supplemental Work & Accessories on a Conjugate Program Decided to write this today as a follow up to my last article which was just kind of a loose and incomplete summary about the conjugate method, how and why to use it. I hate calling things like this a “program” because then people start looking for the cook-book version where every set/rep/exercise is uniformly prescribed in explicit detail for everyone. Unfortunately it generally doesn’t work that way in any program – there has to be some room for individual modifications. And this is especially true for a conjugate routine. This is an organization of training not a paint by numbers program. We’re doing max effort work, speed work for volume, and accessory and supplemental work for hypertrophy, and possibly some conditioning work to maintain enough work capacity to do all of the former effectively. Aside from that it’s really wide open to be individualized. One thing we didn’t get into much on the last article was how to go about organizing your supplemental and accessory type work. The way that most people tend to organize these terms in their head is that “Supplemental” work is the heavier (often barbell based) exercises that come as the second movement each day. These lifts can generally be trained heavy and are similar in execution to the competitive lifts. In the way I design the programs, the exercises we use for supplemental exercises are also exercises that can be used for max effort work (front squats, rack pulls, close grip benches, etc can be used as a supplemental lift or max effort lift depending on the week). On max effort exercises the volume is fairly low and the intensity is very high. I often have clients (after warm up) work up in singles until we hit a 1-rep max for the day (may or may not be an all time PR). Then I may back them off to 85-90% and have them complete 2-3 sets of 2-3 reps as back off. The volume and intensity of the back off work (or even if it gets done at all) depends on the lift and the lifter. If we do a 3″ Deficit Deadlift that takes 6 seconds to lock out and has the lifter’s legs shaking and bursting blood vessels under their eyes…..then we probably drop the back off work entirely or drop the volume/intensity way down. If the top set for the day is a quick smooth single on say a Front Squat….then we may do quite a bit more volume as back off. And we tend to do more back off on exercises that are unfamiliar/new to a lifter just for the sake of technical practice. As a lifter gets stronger and more skilled at a lift, we typically can create more stress with less work and thus the need or ability for tons of back off is less. The supplemental exercise comes next. Usually this is going to be an exercise in the medium-ish volume range (I like around 15 reps for barbell exercises for most intermediates) of like 3 x 5 or 4 x 4, etc. Sometimes this may be higher volume on upper body days, especially if I use Dumbbell Flat/Incline Presses as the supplemental movement, which I often do. Actually very often. Here the volume is like 3-5 sets in the 6-12 rep range. On upper day I often do descending sets (with 3-5 minute rests) as well on exercises like Incline Barbell Presses. I may have them do a max set in the 4-6 range, then peel 10% off and do a set in the 6-10 range, peel another 10% off and finish with a set in the 10-12 range. On the flip side, sometimes volume may also be pretty low on the supplemental exercise on max effort day depending on the lift and the lifter. Especially on lower body day, after a max effort squat variant, I might have a lifter do a Stiff Leg Deadlift or Rack Pull for a 4-8 rep max and then we’re done with that movement. On exercises like this you can often get the job done with one all out set. And remember, on max effort days, it’s okay for the volume to be on the lower side. We’re going to be using higher volumes later in the week on the speed day. Here is a breakdown of where and when the supplemental lift is performed: Monday – Max Effort Lower Body Max Effort Squat Variant or Max Effort Deadlift Variant – 1RM + 2-3 x 2-3 @ 85-90% (optional) Supplemental Squat or Deadlift Variant or Goodmornings – work up to 4-8 rep max or medium load for medium volume (3×5, 4×4, etc) (On max effort squat days I usually use a supplemental deadlift or goodmorning. On max effort deadlift days I usually use a supplemental squat movement) Wednesday – Max Effort Bench Press Max Effort Bench Press Variation – 1RM + 2-3 x 2-3 @ 85-90% Bench Press Variation, DB Bench Press (any angle – flat, incline, or decline), or Weighted Dips 3-5 sets 5-12 rep range. Usually focus here is full range of motion and building up the chest, hence my tendency to focus on DB pressing for volume Friday – Dynamic Effort Squat/Deads Squat 10 x 2 Deadlift 10 x 1 Since we normally squat and deadlift here for up to 10 sets each then we don’t use another barbell based supplemental movement. We move into lower stress accessories Saturday or Sunday – Dynamic Effort Bench Press Bench Press 10 x 3 Shoulder Press or Partial Bench Press Variants (rack press, floor press, board press) or Close Grip Bench Press So on the Dynamic Effort Bench Press days I usually have clients go in one of 3 directions. First, this can be a really good spot to do some heavy and/or high volume overhead work because fatigue levels are only moderate at this point after the speed sets. A good strategy can be to perform one heavy all out set in the 4-6 rep range on the Press, and then back off with 2-4 back off sets in the 8-12 range to really build up the delts. Or skip the heavier set and just focus on building up volume. Or if the lifter has a weak point in their triceps and misses a lot of heavier Bench Presses halfway up…then we can use today to overload the triceps with partial variations. On the Max Effort Day I do use some partial range of motion movements but for raw lifters I like to bias things heavily towards full range of motion exercises. For partials, we normally work for 3-5 sets in the 3-5 rep range with as much weight as you can handle to build up strength in the triceps. It’s okay to maybe work up to a heavier single on these on occasion, but you don’t want to necessarily make a habit of maxing out on Bench Press variations twice per week every week. The third option, which is pretty quick and easy in terms of just being efficient (or lazy if you want to define it that way) in the gym is to just use whatever weight you used for the speed sets and perform like 3 sets of close grip bench presses. Or you can more finely tune the load on the bar by adding subtracting weight so you hit some smooth volume for like 3 sets of 5. So that is kind of the supplemental strategy in a nutshell and as you can see there is almost an infinite amount of ways to organize it. The idea here is arrange things that line up with your individual weaknesses as a lifter and then tailor the volume and intensity to your work capacity, ability to recover, and to match the exercise selection you are using. The accessory work comes next. Accessories, we often call these “assistance exercises”, are going to be lower stress exercises that build muscle mass but minimize systemic fatigue. In my opinion, 1-2 barbell exercises per day is about maximal. Assistance movements generally use dumbbells, cables, machines, or your own body weight. We work with higher repetitions, shorter rest periods, etc. At this point, it’s basically a body building program with an emphasis on building up the muscles that contribute to the big lifts, and there is room even for purely cosmetic work for muscles like biceps and calves if that is something you are interested in. Quads, hamstrings, low back, upper back, and triceps tend to be the areas of emphasis here. How you arrange the assistance work is less important than the fact that you actually do the assistance work and that you are working week to week and month to month to make improvements on all of the exercises in your arsenal. On the upper body days I almost always place a Lat / Upper back exercise as the third exercise of the day while still somewhat fresh. And I usually prescribe a pretty high volume here. 4-6 sets in the 8-12 range is a common recommendation. Rows of all types, chins, pull ups, pulldowns, etc. Along with Deadlift and Deadlift variants on lower body days that hits the back about 4 times per week. With the rows, I often prescribe a lot of chest supported rows or at least variants of rows that don’t fatigue the lower back too much. Since we may be deadlifting up to 2x/week then we have to watch for the fatigue build up in the lower back. Chest supported T-Bar Rows, seal rows, DB rows, chest supported machine rows, Hammer Strength rows, cable rows, etc are all fine. I usually prescribe rows 1x/week and the other day of the week we do something like chin ups/ pull ups or pulldowns. After the rows, then our chest/shoulders/triceps have had a chance to recover a little bit within the workout and so for the fourth exercise of the day I generally prescribe a tricep movement. There are dozens of isolated extension type of movements to choose from and I also like to use a lot of Dips here. I find that doing the tricep movements after all the lat / upper back movement allows the lifter to handle a much more substantial load than if we move right into the extensions after doing say max effort bench presses and dumbbell bench presses. If there is a fifth exercise of the day it is generally lifters choice. We often do stuff here like biceps, rear delts, side delts, shrugs, or whatever. Usually the gas tank is starting to run low here so we’re doing easier stuff. Below is a breakdown of how two upper body days might look in a given week: Wednesday – Max Effort Bench Press 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Max Effort Bench Press Variant – 1RM + 2-3 x 2-3 @ 85-90% Incline DB Bench Press 3-5 x 8-12 Chest Supported T-Bar Rows 4-6 x 8-12 Lying Tricep Extension 3 x 8-12 Side Delt Raises 3-5 x 15 Saturday / Sunday – Dynamic Effort Bench Press 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Bench Press 10 x 3 @ 60-70% Standing Overhead Press 4-6 RM + 3 x 8-12 Chins – 50 reps in as many sets as it takes or Pulldowns 5 x 8-12 Dips – 3 sets max reps with body weight Bicep Curls 2-3 x 10-12 If you read a lot of the traditional material from Westside Barbell, there is going to be a very heavy emphasis on hamstring and lower back work on lower body days. This is important for raw lifters, but raw lifters also benefit from training the quads as well. For many of my clients the extra Quad work also satisfies some of their physique / aesthetic goals as well. I’ve written before about the “Turnip Look” that can be the result of heavy emphasis on low bar squatting and deadlifts. Genetics / structure play a big role in this as well, but many of my clients don’t like the look of having small quads and a big ass. I’ve found that for many (including me) the quads grow a lot better with traditional body building exercises such as leg presses, hack squats, and leg extensions in the 10-20 rep range (high bar squats as a supplemental movement after max effort deadlifts are also useful for growing the quads). I usually put one exercise for the quads on both lower body days. Hamstrings and lower back are already getting a lot of work on the max effort day and for this reason I train the hamstrings on this day with a knee flexion exercise such as a leg curl or glute ham raise and avoid more hip extension work. On the Dynamic Effort lower body day I have my clients do lower stress hip extension movements such as 45 degree back raises and reverse hypers for higher reps. I have found this to be extremely beneficial for building up work capacity in the lower back so that lower back fatigue does not become a limiting factor for the max effort, supplemental, and speed work. Sessions are often rounded out with optional calf and ab work. One note for older lifters, athletes, or just lifters that struggle with recovery for whatever reason……. Lifters often avoid assistance exercises for the lower body. My clients tend to LOVE LOVE LOVE doing lots of “bro work” for the chest, arms, shoulders, etc because (1) it’s not as hard (2) they like the “look” that it creates. People are less enthusiastic about high reps and volume for the legs. Mainly because (1) it’s hard (2) recovery is more difficult (3) they aren’t as into the aesthetics of their lower body vs upper body as long as they don’t have stick legs. And if you squat / pull twice per week you aren’t going to have stick legs. For this reason, many lifters forgo the bodybuilding type approach for training the lower body and may just focus on things like pushing a Prowler or dragging a sled as a substitute for lower body assistance. This can be an effective method and recovery will likely be easier. Sleds/Prowlers don’t have the same eccentric stress that say Hack Squats do and thus soreness through the week is less. So you might experiment with something like that. On max effort day….hit a max effort and supplemental exercise and then go drag the sled. On speed day…hit 10 sets of squats and speed pulls and then go push the prowler. I might still suggest some dedicated low back work on the 45 degree bench or reverse hyper though since sleds/prowlers are mostly quads, hams, glutes, calves. Here is a breakdown of how the lower body can be trained using the conjugate method: Monday – Max Effort Lower 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Squat or Deadlift Variant – 1RM + 2-3 x 2-3 @ 85-90% (optional) Squat or Deadlift Variant or Goodmorning 3 x 5 Leg Extensions 3 x 15 Leg Curls 3 x 10 Calf Raises – 50 reps broken up Friday – Dynamic Effort Lower 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Squat 10 x 2 Deadlift 10 x 1 Leg Press, Hack Squat, or Belt Squat 3 x 10-20 45 Degree Back Extension or Reverse Hyper 3 x 15-20 Abs Hopefully this clarifies some questions that lifters have about organizing assistance and supplemental work as part of a conjugate routine. Choose Weakness Over Strength What the hell are you talking about, Baker? I'm talking about exercise selection. 99% of us like to pursue the things we're good at and that we're comfortable with. And this of course extends into the gym. But I'm telling you that if you only focus on the exercises that you Know, Like, and Trust you are leaving progress on the table. If you're following my Conjugate Training routine (or any other routine), don't just choose exercises off the menu that you're good at. Get good at the things that you suck at. Most of the new members of my club HATE when I prescribe them Front Squats as a supplemental or max effort exercise. Why? Because maybe they're a 405 back squatter who can barely Front Squat 185. That's indicative of some serious weaknesses my friend. Maybe it's your abs. Maybe it's your back. Maybe it's your quads. So get better at Front Squatting and these weaknesses are no longer weaknesses. And what happens - Deadlifts go up. Squats go up. You have become stronger. Are you getting stronger? If not, try getting out of your comfort zone. Pick an exercise you hate and go to fucking war with it for 12 weeks and see what happens. Go get it. Use What You Got! (Conjugate Method in the Garage Gym) Contrary to what you might think, you don't have to train at Westside Barbell or the EliteFTS warehouse in order to train with the Conjugate Method. You can do it right there in your garage or basement gym if you understand the system. People often associate the method with all the crazy shit they see on YouTube and Instagram. 12 different types of squat bars.....bands....chains.....foam boxes.....etc, etc. Kettlebells hanging off the end of a bamboo bar. They think THAT is the method. It's not. You don't have to have all that shit. You don't have to have any of it. Here is what you need to know.......... On the Max Effort Days you need to STRAIN against a heavy load. A heavy single is ideal. But you can't strain on that heavy single on the same exercise every week. The absolute load on the bar MUST oscillate every week (or at a minimum every 2-3 weeks), hence the need to frequently rotate exercises. You can achieve this simply by changing a few very simple variables such as grip width, stance, or the use of pauses. Here is a sample 8 week Max Effort Cycle for the Bench Press Week 1: Touch n Go Bench Press (pinkies on rings) Week 2: Close Grip Bench Press (index finger on the smooth) Week 3: Incline Bench Press (or sub with seated overhead press if no incline bench) Week 4: Close Grip Pin Press (2-3 inches off chest) Week 5: 3-5 count Paused Bench Press (pinkies on rings) Week 6. Medium Grip Bench Press (thumbs distance from smooth) Week 7: Standing or Seated Overhead Press Week 8: Floor Press This is just a sample but there are many, many more variations you can use. No bands. No chains. No specialty bars. Basically just grip varying grip widths, pauses, and angles and you've got a complete 8-week training cycle. You got this!! Garage Gym Conjugate Training (Lower Body Edition) Wednesday I gave you a sample 8-week training cycle for the Bench Press that would work in most any garage or basement gym. I thought it'd be kind of a dick move to not include a lower body training cycle as well. Like a lot of trainees who get burnt out with the same old exercises week in and week out, you might be interested in trying out all this Conjugate stuff to get yourself out of a rut. It seems exciting and fun, but maybe too complex? It's not really. Every week, select a variation of the Squat or Deadlift and Bench Press and work up to a top single. Rotate exercises every 1-3 weeks. That is max effort day in a nutshell. Where people get their brain tied in knots is in exercise selection. They see all the crazy shit on social media with bands, chains, goofy looking barbells, and get gun-shy. But you don't need to outfit your garage or basement gym with thousands of dollars of new equipment to follow the conjugate program. Here is a sample 10 Week Max Effort Lower Body Training Cycle: Week 1: Competition Squat (low bar) Week 2: Deadlift (conventional) Week 3: Front Squat Week 4: Sumo Deadlift (medium stance) Week 5: Close Stance High Bar Squat Week 6: Snatch Grip Deadlift Week 7: Paused Pin Squat or Box Squat Week 8: Rack Pulls (mid-shin to below knee) Week 9: Competition Squat (no belt, 3 sec pause) Week 10: Deficit Deadlift (stand on 2-4 inches of boards or mats): You don't need anything to do this training cycle other than a barbell and a power rack. And a willingness to try some new things and get out of your comfort zone. If you're current training isn't delivering for you, there is no reason not to try a different approach! 3 Favorite Lower Body Supplemental Lifts Since I started sending out emails last week about what my crew has been doing with the Conjugate Method, I've had a flood of questions about some of the specifics of the program. In particular, people are really curious about the format for assistance and supplemental work. When I refer to supplemental exercises I'm generally referring to the heavier barbell variations that follow the max effort movement. A few pointers to remember here: 1. Pick exercises that resemble the Big Lifts in mechanics and in load 2. Build technique on unfamiliar max effort movements by training moderate weights at moderate volumes 3. Be aware of fatigue build up Here are 3 of my faves: 1. Front Squats: o Use for sets of 3-5 reps after a max effort deadlift variant. o The upright position is less impacted by the low back fatigue of deadlifts. o Lighter by nature and produce less systemic fatigue than back squats. o Hammer the quads which may be neglected to a degree by deadlift variants. o People suck at these. More practice as a supplemental can lead to bigger numbers when used as max effort 2. Romanian Deadlifts o Use for sets of 5-8 after max effort squat variant o Hammer the hamstrings with a less fatiguing exercise than deadlifts from the floor o An important movement but a poor choice for max effort work. Pure hip extension movements can be dangerous at very low rep ranges 3. Goodmornings o Use for sets of 5-8 after max effort squat variant o Hammer the hamstrings with a less fatiguing exercise than deadlifts from the floor or RDLs o An important movement but a poor choice for max effort work. Pure hip extension movements can be dangerous at very low rep ranges o A great movement if you want heavy hamstring work without the bar in your hands An easy transition from a squatting movement. Saves transition time in the gym. Why You Should Train the Floor Press If you've been reading my emails lately about Conjugate Training you know that you need a diverse stable of exercises to rotate through on your Max Effort training days. For every Max Effort Bench Press session you'll be working up to a heavy single / 1-rep max for the day. If you are going to employ this strategy you know you can't just Bench Press every week for a 1-rep max. You need to max out on a different exercise each week. Ideally each week some aspect of the movement pattern will change. We can change the grip width, we can change the angle of the bench, we can use a specialty barbell, or we can perform some sort of partial range of motion. The Floor Press is a great exercise, that just about everybody can and should add to their rotation of max effort movements. Here's why: 1) No special equipment. If you have a rack and a barbell and a floor you can do this movement. The only exception to this would be the pin hole setting in your power rack. If the holes aren't low enough you can't set the j-hooks in a position where you can rack / rerack the barbell. Additionally, it's a good idea to be able to set the safeties low enough to catch the barbell in the case of a missed rep 2) Little to No Stretch Reflex. In an earlier email I made the point that your max effort movements should be harder than the actual Bench Press. The Floor Press is hard because it builds raw pressing power without the aid of the stretch reflex. This is partly due to the fact that you need to pause each rep but also because the floor will prevent you from getting the stretch from the pecs needed for a big stretch reflex. 3) Little to No Leg Drive. Read #2. You can perform these with bent knees or make it even harder by keeping legs straight. 4) Trains the Sticking Point. Typically the Floor Press stops the bar in a place where most people stick on a heavy bench press. Maybe 1-3 inches off the chest although this varies based on your build. 5) Can be used for 2-4 variations for your rotation. Close Grip or Competition Grip. Knees Bent or Knees straight. If you don't have a lot of equipment you can use the floor press to create 2-4 different variations for your rotation of max effort day movements. Programming Which Program Is Right For You? In this article, I’ll attempt to clarify which of the programs for sale on AndyBaker.com is best suited to your goals. If you are trying to decide on a program to purchase but you aren’t sure which one to pick, this should help give you some insight. Garage Gym Warrior This is by far my most popular and best selling program and the program which I get the most positive feedback from. Who is this program for? Any intermediate trainee. This is a classic Heavy-Light-Medium program focused purely on building and peaking strength in the Squat, Deadlift, Bench Press and/or Press. This program is ideal for lifters who train with minimal equipment and like the structure of a 3-day per week full body routine. This program is extremely effective for older trainees with limited recuperative abilities or trainees who are trying to balance stressful personal/professional lives with training. There are some hard weeks, but overall the program does not require exhaustive effort physically or mentally. This program is very straightforward in that the entire cycle is laid out for you with strict sets, reps, and percentages to follow for loading. If you don’t like to “think” about your training too much, this is the way to go. As laid out, this program is pretty “bare bones”. It’s just the major barbell lifts with very little assistance work outlined. However, you can add assistance work to this if you like. How to use this program? This is a good baseline program to run for the bulk of the year if basic strength is the goal. It can be repeated for multiple cycles in a row with very simple adjustments to sets, reps, and loading. In my article series on Annual Periodization, this would be a good program to use for basebuilding at the beginning of the year, or during the summer months, between more aggressive peaking programs if you aren’t interested in doing any power-builiding / hypertrophy based training. KSC Texas Method & KSC Method for Power-Lifting Who is this program for? KSC Texas Method – early intermediate trainees KSC Method for Power-Lifting – late intermediate / advanced trainees. Both programs are fairly short term and aggressive peaking programs which involve alternating between higher volume sessions and higher intensity sessions. The KSC Texas Method is more “bare bones” in that it involves very little to no assistance work and operates on the classic 3-day per week full body programming model. However, it can be modified into a 4-day per week program. Percentages, sets, reps are all laid out for you in a very easy to understand manner. The KSC Method for Power-Lifting is a 4-day per week program (although it can also be modified for a 3-day per week schedule) and involves a bit more assistance work and some higher-rep hypertrophy work thrown into the week. It’s a bit more nuanced than the Texas Method, but still pretty straight forward. If you like a bit more variety in your training, do the KSC Method for Power-Lifting. If you want something very straight forward and “done for you” do the Texas Method program. How to use these programs? It’s best to use these programs for just 1-2 cycles before transitioning to something with a little less frequency on the intensity side of the spectrum. Both programs call for you go heavy on a weekly basis. This is very effective in the short term (like before a meet), but is not the best solution for year round / long term usage. Alternated with with cycles of something like the Garage Gym Warrior program, both programs are very effective additions to your annual plan. In my article series, I suggested that the Texas Method be used for a strength peak in the spring, and the KSC Method for Power-lifting be used for a strength peak in the fall. This strategy works well. KSC Method for Power-Building and Strength & Mass After 40 Although these are two very different programs, they are based on a similar model. Both systems use a 3-week rotation of different rep schemes for the strength movements, layered with a moderate to high volume of assistance work for hypertrophy and physique oriented training. Who are these programs for? KSC Method for Power-Building: Intermediate / Advanced Trainees focused on strength with a massive emphasis on building mass and physique development. Strength & Mass After 40: Intermediate / Advanced Trainees focused on strength with some additional hypertrophy work The Power-Building program uses my very popular system of rotating 8s, 5s, and 2s in 3week waves along with lots of higher volume assistance work. The weekly training is a 4-5 day per week body part split organized like this: Monday – Bench + Chest/Biceps Tuesday – Deadlifts / Squat + Hamstrings, Calves, Abs Wednesday – Off Thursday – Press + Shoulders/Triceps Friday – Back / Lats Hypertrophy Day Saturday – Squats + Quads, Calves, Abs Sunday – Off The program is very difficult but very effective for both size and strength. Strength & Mass After 40 uses a model of 5s, 3s, and 1s on a 3-week wave. This is a 4-day per week plan that operates off of a Heavy – Light split (each lift performed 2x/week, once heavy, once light) plus some higher volume assistance work for hypertrophy in a dose more appropriate for older lifters. How to use these programs? Many lifters have had success running several cycles of the Power-Building program followed by the Strength & Mass After 40 program where intensity on the main lifts is increased and the volume of assistance work is decreased. This strategy has worked well for trainees over 40 as well as younger trainees. Younger trainees may do long periods of time with the higher volume Power Building program followed by short spurts of the SM40 program. Older lifters can do just a few high volume cycles of the Power-Building program followed by longer stints with the SM40 program. Trainees have had good success running both programs as a base-program for many months at a time. A simple lower volume, lower intensity deload week every 6-12 weeks is enough to keep you running for long periods of time without overtraining. A Sample Annual Plan January – March: Garage Gym Warrior or other Heavy-Light-Medium Program April – May: Strength Peaking with KSC Texas Method June – August: Strength / Physique / Hypertrophy Training with KSC Method for PowerBuilding Sept – October: Strength Peaking with KSC Method for Power-Lifting Nov-December: General Strength / Hypertrophy with Strength & Mass Over 40 Short Guide To Intermediate Programming If there is one area in programming where most people get “stuck” it’s as an early intermediate trainee. When I answer questions via email, answer questions on the Starting Strength Programming forum, or design custom programs for clients, I’d say a good 80% of the time these trainees are having issues/difficulty with the first few months of intermediate level programming. There are a few reasons for this. First and foremost is that there is no clear cut “program” that is going to work for every individual trainee at the intermediate level. The further and further along one gets in their training career the more individual factors start to come into play that influence program design / program selection. Age, attitude, physical ability, aptitude, genetics, goals, etc start to play a more significant role at the intermediate level and they play a major role at the advanced and elite levels. Thanks to Mark Rippetoe and the Starting Strength program, we have a pretty good blueprint for what works optimally at the novice level. Through 30+ years of experience and analysis, Mark has put on paper something that coaches and trainees can use that works with just about everybody. With only a few minor modifications here and there for each individual, we (the overall community of strength/fitness professionals) haven’t really come up with anything that works better than the Starting Strength linear progression for those initial gains in strength and muscle mass. Maybe in the future, we come up with something new and improved, but I haven’t seen it yet. Do other programs work for novices? Sure. But with novice trainees we are looking for our program to deliver one thing above all else – speed. What I mean by speed is – rapid progression. Novices are capable of getting very strong very fast. More precisely – novices are capable of creating new performance increases about every 48-72 hours. Any program that asks for a display of increase performance at a slower rate (for example – once per week) is less than optimal. So it doesn’t mean that other programs don’t work – they just work slower. Why make gains slowly when you can make them quickly? As a novice, specific goals are not factored into program design as they are at the intermediate and advanced levels. Because any specific goal is first predicated on laying the basic foundation of general strength and increased muscle mass, it isn’t necessary to worry about the specific until we have addressed the general. And the Starting Strength linear progression is, to date, the best general strength training program available. However, as many of you reading this article will acknowledge, those easy novice gains don’t last for long and the insanely simple programming model of the Starting Strength linear progression has a shelf life. In about 3-9 months you are done with that program. It won’t work anymore. And now we’re much stronger, but we’re paralyzed by a litany of choices on what to do next. As we laid out in Practical Programming for Strength Training, there are lots of options available to intermediate trainees. And much to the frustration of trainee and coach alike, sometimes we try something that looks good on paper and it simply doesn’t work in practice. What we planned on doing for the next 6 months doesn’t last for 6 weeks before we are stalled out, burned out, and stuck! Unfortunately there is no intermediate or advanced program that works for everyone in the way that the Starting Strength program pretty much works universally for novices. So here’s a few helpful guidelines to follow for those of you who are no longer novices, but haven’t quite figured out how to master intermediate level training to keep progress going. #1: Read the F*cking Book! I know that many of you reading this have a copy of Practical Programming for Strength Training (PPST3) floating around your house or office somewhere. I also know that a large number of you skipped right over the first half of the book and jumped right into the sections on specific programming examples. As some say, you skipped over the fluff and went right into the meat and potatoes. Big mistake. The “fluff” in PPST3 is designed to give you a big picture overview and a broad understanding of how programming works at the novice, intermediate, and advanced levels. You need to know this stuff if you are programming for yourself. You also need to read the book correctly! What I specifically mean by this is how some people read the “programs” section of the book. None of the programs in PPST3 or in the new book The Barbell Prescription: Strength Training for Life After 40 (BP40) are meant to be prescriptive for any single individual. They aren’t cook books. They are illustrative examples of how a specific type of program might look in operation. But each of those specific programs in the back of the book are meant to be modified and tailored to the individual. But you won’t be able to modify the programs at the back of the book correctly, if you don’t have a clear understanding of the information presented in the front of the book!!! This is the crux of the problem for many of the clients I consult with. #2: Identify Your Individual Goal and Train for it Appropriately I basically break clients/trainees down into 4 different categories and then the programs I design for them are based on these goals. 1. Pure Strength 2. Physique/Aesthetics/Mass 3. Performance/Sport 4. General Health/Fitness Pure Strength These could be competitive lifters in the strength sports, or just a guy in his garage that really wants to put up some big numbers on a core group of barbell lifts. But the ultimate goal is the same – weight on the bar. In general, these lifters are going beyond what they need to do for the purposes of general health and fitness which doesn’t require a 600 lb deadlift. These lifters want to put up big numbers because…..well, they just want to. Mainly because being really strong is really useful and really cool. But for pure strength training, the focus of the program is only on a small assortment of competitive lifts and maybe a very small pool of assistance or supplemental movements that aid in the performance of those lifts. No other factors are interfering with the acquisition of more weight on the bar. An early intermediate trainee who is training for pure strength needs a blend of both volume and intensity with the main barbell exercises. For this purpose, I really like the good ole’ Texas Method. The Texas Method is a lifters program. It’s hard. Brutally hard. But it works really well. And it’s described in detail in PPST3 so I’m not going to rewrite the protocol here. I like the standard 3-day method (especially for powerlifting) because it is so easy to manipulate and adjust. And I like having the mid week light day for most early intermediate trainees. But there are some drawbacks to the 3-day Texas Method. As I already stated, it’s really hard. It’s difficult to recover from. If you aren’t a competitive lifter or very serious strength trainee you probably don’t have the mental fortitude to make it work over a long period of time. If you are over 40 years of age (or hell, even over 30), you might also have some difficulty with the program. The other drawback is that the workouts take a long time. Again, if you aren’t super serious about this shit, you may not have 2 hours of training time for a heavy volume day. So there is the 4-day Texas Method (also described in PPST3) which shortens the workouts and makes recovery easier. Instead of 3 full body workouts each week, you have 2 upper body workouts and 2 lower body workouts. If you are 30+ years of age, I’d probably opt for the 4-day Texas Method in most cases. After many months of the 4-day Texas Method, you might need to switch to a 4-day Heavy/Light routine. Its very similar in structure to a 4-day Texas Method, but only has you performing each lift heavy/hard 1x/week rather than 2x/week. If you like the 3-day a week / full body format, but are limited on training time or if you are 40+ then a Heavy-Light-Medium program makes sense. HLM programs are easier to recover from than a Texas Method program. (Extra Help? A simple and easy to follow HLM template is used in my Garage Gym Warrior Program ) So to clarify for pure strength athletes: 3 Day Texas Method – brutally hard, but very effective and simple to program. Best for serious lifters under 30. 4 Day Texas Method – still very hard, but shorter workouts make recovery more manageable. 4 Day Heavy/Light – logical next step when progress on 4-Day Texas Method becomes too difficult. 3 Day Heavy-Light-Medium. Easier to recover from the 3-day Texas Method. Better for lifters who are over 30. Physique/Aesthetics/Mass For those whose primary purpose in training is a massive overhaul in their physique, then we need to do a few other things other than just train the main lifts heavy. We need more volume, particularly some higher rep type of volume work, and we need a few more exercises. Make no mistake, if you want to get bigger you still need to keep getting stronger. But you need to keep the pure strength work in balance with the training you will do for your physique. You can’t just take an already brutally hard program like the Texas Method and pile on a bunch of assistance exercises and higher rep work on top of everything else. Its just too much. This is where split training becomes necessary. It can be a very basic split of upper/lower body spread out over 4-days per week or something even a little bit more specific – arranged by body part. Split routines get a bad rap as being “all fluff” or “just for the guys who are juicing” or “bullshit from the bodybuilding mags” and sometimes this is true. But the devil is in the details. A good split routine, built around the foundation of the heavy barbell lifts, is, in my opinion the best way to train for physique. There really isn’t another practical layout for a routine that needs to address the big lifts plus the development of all the smaller muscle groups. Split routines will generally have an athlete training 3-5 days per week. In my KSC Method for Power-Building program I have the program organized into 5 different workouts. 3 for upper body, and 2 for lower body. In the program, you can train Monday-Friday like this: Monday – Chest/Biceps Tuesday – Lower Body (Deadlift focused) Wednesday – Shoulders/Tricep Thursday – Upper Back (lats, traps, etc) Friday – Lower Body (Squat focused) Or you could train 2 days on, take Wednesday off, and then 3 days on with Sunday off. Performance/Sport Sport athletes have a balance they must walk too. Conditioning for their sport and practice/game play of their sport compete for recovery resources with the weight training program. For this reason, we should also probably avoid trying to train on the most demanding barbell programs. Again – it probably won’t work. So I’m not a fan of trying to run through the Texas Method while competing in/training for sports. Sport athletes don’t need all the specific body part work that a physique athlete needs either, so split routines aren’t really the best approach either. In my opinion, a 3-day per week Heavy-Light-Medium program is best. This allows athletes to stay focused on just the primary barbell exercises, while limiting some stress. Plus, an HLM program is very flexible. You can organize it around your sport, and even select exercises you think might help you with your sport. For instance, I’ve used something like this for athletes who compete in shot put and discus in the past: Monday – Heavy Squat, Medium Press (Push Press), and Light Pulls (Power Snatch) Wednesday – Light Squat, Heavy Press (Bench Press), and Heavy Pulls (Deadlift) Friday – Medium Squat, Light Press (strict military), and Medium Pulls (Power Clean) General Health/Fitness In my experience, this is largely the goal of many of my personal training clients over the years, most of whom are 45-75 in age. For this demographic, they aren’t really interested in pulling a 600+ lb deadlift or benching 405. It’s about maintaining a high quality of life and feeling great outside of the gym. For these people, strength training may or may not be a passion like it is for some of us. It’s viewed more as “something I need to do to stay healthy.” Kinda like eating your vegetables as a kid. So I don’t really want them to commit to a strenuous 3-4 day per week program. They’ll burn out mentally and physically. A two day per week full body program will get the job done. They’ll still get the results/benefits of getting stronger and making some aesthetic changes to their body, but they’ll easily recover from the workload and feel good outside the gym too. Something as simple as this can be effective for a long period of time: Monday – Heavy Squat, Press, Chin Ups Thursday – Light Squat, Bench, Deadlifts In our new book The Barbell Prescription: Strength Training for Life After 40 we have TONS of examples of 2-day per week programs appropriate for trainees in their 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s, and even 80s. A Plan For Annual Periodization (Part 1: January – May) As we get closer to the start of the new year, there will no doubt be thousands of people around the globe who are sitting down to re-assess their goals and their training plans for 2018. My hope is that this article might potentially serve as a guide for some of you to think about how you might set up your next year of training in a way that is logical, productive, and dare I say even fun. The truth is that no single training plan generally works for 12-months at a time without serious manipulation and modification during the year. Adjustments in volume, intensity, and frequency must be made continuously to avoid stagnation and keep progression going. So for those of you who just want to pick one training program and run it all year long on “auto-pilot”, I hate to break it to you, but it usually isn’t that simple. For those of you on the other side of the spectrum that just want to “wing it” for the next year, well that typically doesn’t work either. Some degree of planning needs to be in place or you’ll wind up spending 2018 as a Chronic Program Hopper without much rhyme or reason as to why you are doing anything. Most of you are aware of the basic programming models presented in Practical Programming for Strength Training such as The Texas Method, Heavy-Light-Medium Training, and Split Training Routines. There are of course many many other methodologies that work, but we’re going to keep the discussion fairly narrow and I’ll suggest some ways in which to implement all 3 of these programs throughout the year in a way that works. Keep in mind that my suggestions are coming from a perspective of having implemented all of these routines with 100s of clients in the gym over the course of a decade. I take into account certain “realities” of working with regular people such as summer travel schedules, holiday travel schedules, and people’s physiological and psychological need to vary their training routine over the course of a year. For those of you who are coaches, personal trainers, or gym owners, this article might be helpful to you as a guide to keep your clients engaged over the course of a year rather than getting burnt out and bored with the same old – same old. Let’s start with January 1, and where most people will be physically and mentally. Coming off the holiday season many of you or your clients will be starting the year detrained, deconditioned, but motivated to hit the weights hard. I like to ease my clients back under the barbell with a basic Heavy – Light – Medium program to start the new year. I like the frequency of the program in order to get people dialed back into their form and technique on the basics. I feel like the volume of the programming and the relative “ease” of some of the training days is also appropriate, as we don’t want to start things off with a lot of higher intensity work for people who may have lost some of their base level of conditioning to barbell training program. What I like to do is spend about 12 weeks or so (could be a bit more or less) starting with moderate volumes and moderate weights and building up with some slight increases in volume and intensity over the course of the 12 week period. This will roughly take you from January thru March. So let’s look at three 4-week blocks of training to get you or your clients started for the new year. (Only Barbell exercises shown, add in small doses of assistance work at your discretion). Block 1 (4 Week) Monday: Heavy Squat 4 x 6, Heavy Bench 4 x 6, Medium Deadlift 3 x 6 Wednesday: Light Squat 2 x 6, Heavy Press 4 x 6, Barbell Rows 4 x 8 Friday: Medium Squat 3 x 6, Medium Bench 3 x 6, Heavy Deadlift 2 x 6 * For heavy days, loads should start around 70-75% of 1RM (or just whatever you can do for the given rep range and increased week to week. Light Days are ~10-20% less than you heavy day, and medium days are 5-10% less than heavy days). Block 2 (4 Weeks) Monday: Heavy Squat 5 x 5, Heavy Bench 5 x 5, Stiff Leg Deadlift 4 x 6 Wednesday: Light Squat 3 x 5, Heavy Press 5 x 5, Barbell Rows 5 x 8 Friday: Medium Squat 4 x 5, Close Grip Bench Press 4 x 6, Heavy Deadlift 3 x 5 *Loading will increase slightly into the 75-80% range for most work and increased week to week) Block 3 (3-4 Weeks) Monday: Heavy Squat 6 x 4, Heavy Bench 6 x 4, Stiff Leg Deadlift 5 x 4 Wednesday: Light Squat 4 x 4, Heavy Press 6 x 4, Barbell Rows 6 x 6 Friday: Medium Squat 5 x 4, Medium Bench Press 5 x 4, Heavy Deadlifts 4 x 4 *Loading will increase into the 80-85% range and increased week to week The HLM program usually ends with a pretty giant dose of volume and you may only be able to sustain it for 3 weeks rather than 4. HOWEVER. The key with this program is the volume and not necessarily load. So adjust your weights accordingly so that you can get your sets and reps in for the prescribed volume. If that means increasing your offsets for light/medium days or the use of back off sets for the really high volume days instead of sets across then you should do so. Also, note that I prescribed loads in the 70-85% range, and most of the work probably average out closer to 75-80% so you should not really be “grinding” out every set of every workout. And of course, the exact sets and reps can be adjusted for the individual. Most of those adjustments would be in the direction of slightly less volume and not more. This amount of volume should be sufficient for most trainees. Before starting the next phase of training, I suggest a one week deload (probably last week of March) to rest up a bit. Simply train twice per week with less volume, but keep loading somewhat high around 80-85%, or right around where you ended the HLM program. So if you ended your HLM program squatting 6x4x350, then you might just squat 3 x 3 x 340. This will allow fatigue to dissipate but not encourage a detraining effect. I suggest to only deadlift 1 time during the deload. April – May: The Texas Method The extremely high volume HLM program that we ended with sometime in March will dovetail beautifully into a lower volume but higher intensity Texas Method program that will culminate in a “peak” sometime in May, usually before the summer travel months begin. I don’t like to schedule big strength peaks in the summer time because adherence is often compromised for clients who miss gym time June – August. Again, dealing in reality here. As the fatigue from the volume of the HLM program begins to dissipate in April with lower volume training it serves as a catalyst for some nice PRs in the 1-3 rep range that are kinda the hallmark of a Texas Method program. The Texas Method is rough, but it works well, especially if you time it right in an annual plan. Not as a yearly program, but for short bouts of 8-10 weeks or so, it’s wonderful for peaking strength or prepping for a meet. We’ll keep a very similar structure to the HLM program, but some of the medium day workouts will transform into Intensity Days for the next several weeks. I like to plan for about 9 weeks on the Texas Method, with the final week being a combination of deloading and testing. I prefer a 3-week cycling of both volume and intensity, although you can run a more straightforward approach to the Texas Method as well, such as those presented in PPST3. Week One: Monday: Volume Squat 5 x 5-6 (~75%), Volume Bench Press 5 x 5-6 (~75%), Stiff Leg Deadlift 3 x 6 Wednesday: Light Squat 3 x 5 (-10-20%), Press 5 x 5-8, Chins 3-5 x max Friday: Intensity Squat 1-2 x 3 (~90%), Intensity Bench Press 2-3 x 3 (~90%), Deadlift 1 x 3 (~90%), 1 x 5 (~75-80%) Week Two: Monday: Volume Squat 5 x 4-5 (~80%), Volume Bench Press 5 x 4-5 (~80%), Stiff Leg Deadlift 3 x 6 Wednesday: Light Squat 3 x 5 (-10-20%), Press 5 x 5-8, Chins 3-5 x max Friday: Intensity Squat 1-3 x 2 (~92-93%), Intensity Bench Press 2-4 x 2 (~9293%), Deadlift 1 x 2 (~92-93%), 1 x 5 (~75-80%) Week Three: Monday: Volume Squat 5 x 3-4 (~85%), Volume Bench Press 5 x 3-4 (~85%), Stiff Leg Deadlift 3 x 6 Wednesday: Light Squat 3 x 5 (-10-20%), Press 5 x 5-8, Chins 3-5 x max Friday: Intensity Squat 3-5 x 1 (~94-96%%), Intensity Bench Press 3-6 x 1 (~9496%), Deadlift 1 x 1 (~94-96%), 1 x 5 (~75-80%) Weeks 4-6: You will basically repeat the previous 3 week cycle, but add small amounts of load across the board to both volume and intensity days of each week. Weeks 7-8: You will basically repeat weeks 4 and 5 of the previous 3 week cycle, but add small amounts of load across the board to both volume and intensity days of each week. Week Nine: Tuesday: Volume Squat 3 x 3, Volume Bench 3 x 3 (Repeat loads from previous weeks volume day) Friday or Saturday: Test 1RMs for the Squat, Bench, and Deadlift in a meet or mock-meet format. *Note: It is difficult to use %’s with exact precision on a Texas Method based program. Use them as a reference point and weigh them against the numbers you put up during your HLM program. Use those two points of reference to “script” out the numbers you will be using for your volume and intensity days on the 9 week Texas Method program. My suggestion is to avoid making it up as you go along. In part two we will look at using a split routine for the summer months, another strength peak in the fall, and then look at some simple strategies for training through the holidays. For some “Done For You” Heavy-Light-Medium and Texas Method programs, I invite you to look at the following programs: Garage Gym Warrior (Heavy – Light – Medium). Note that the GGW program is slightly different than what I laid out in this article, but the basic premise is the same. The GGW program ends in a testing day, and I would recommend omitting that day prior to beginning the Texas Method. The KSC Texas Method is very similar to what I laid out in this article, complete with how to properly set up 3-week waves for volume and intensity days. A Plan for Annual Periodization (Part 2: June – December) In Part One of this article we looked at a simple strategy to get back to serious training at the beginning of the New Year. We begin by easing back with somewhat high frequency, moderate/high volume Heavy-Light-Medium program with most of the loading occurring between 70-85% of 1RM. This is ideal for building back a solid base of strength, muscle mass, and conditioning to barbell training. As the volume peaks fairly high somewhere in March, we leverage that high volume training as a leap off point for a slightly lower volume / higher intensity Texas Method program which is designed to peak strength some time in May. Although the Texas Method has gotten a bad rap as of late, I still like it and use it regularly with clients. It’s not an ideal training system for year round use, but for short periods of time, especially on the back end of a higher volume / lower intensity program it works well and is easy/simple to implement. It’s still my go-to program for my powerlifting clients prepping for meets. By the time our hypothetical trainee reaches summer time they are likely SICK of 3-day per week barbell only training. Let’s face it…. Squatting/Pressing/Pulling gets really old after a while for most of us. It can wear you down physically and mentally. June – August / September – Split Routine During the summer months a good annually periodized program can include the use of a Split Routine to introduce some variety into the program while preserving those hard earned strength gains you made January – May. Split Routines allow us to do a few things that are appropriate for this time of year. As I just mentioned – they can reduce the frequency of some of the main barbell exercises giving your mind and body a much needed break. Second, split routines allow for the introduction of some higher rep range assistance exercises which don’t always pair well with 3-day per week full-body training. As we just peaked our strength in May, we can now leverage some of that strength into some higher rep training with actual meaningful loads. This will help you pack on some new layers of muscle mass which you can carry with you to the next strength peak in the fall. And let’s be real here…most of you guys would like to look better at the pool or the beach this summer. Even if you won’t admit it. We’re all a little vain and it’s okay to want to “look like you lift.” During these summer split routines you can focus on some physique oriented training on top of your basic strength training routine. Here is another reality. People vacation and travel during the summer months and often miss training. For this reason, I don’t like running programs where missing several weeks over the course of a 12-18 week block of training can derail a program in terms of throwing off all the numbers. Physique/Mass training doesn’t have to be as precise in terms of hitting certain numbers on specific days on specific lifts. People training in less than ideal situations such as hotel gyms, small 24/hour gyms, etc can go in and work a body part or a handful of body parts with less than ideal equipment and still stick to the program….more or less. So if you are forced to Leg Press rather than Squat or do DB Bench Press instead of Barbell Bench Press – no big deal. Just hit the body part hard and call it a day. For optimal physique/mass gains I actually like a 5-day training split. This is a lot, but keep in mind that most sessions are limited to just 1 or 2 main barbell exercises followed by a handful of body part specific accessory exercises used to build up smaller muscle groups. You don’t have to do 5-days, you can pair this down to a 3 or 4 day per week program based on your schedule. Here is an example 5-Day Training Week from similar to what I lay out in the KSC Method for Power Building: Monday: Bench Press + Chest/Biceps Bench Press – 3 work sets of 8, 5, or 2 Incline Bench Press or DB Incline Press 3-5 x 8-12 Barbell Curl 3-5 x 8-12 Dips – 50 reps in as few sets as possible Incline DB Curl 2-3 x 8-12 Tuesday: Deadlift + Hams/Low-Back/Calves/Abs Deadlift or Deadlift Variation – 3 work sets of 8, 5, or 2 Box Squat or Deadlift Variation – 3 work sets of 5-8 Light Posterior Chain – back extensions, glute ham raise, reverse hyper, leg curls, etc – 50-100 reps in as few sets as possible Abs/Calves – whatever Wednesday – OFF Thursday: Press + Delts/Tricep Press – 3 work sets of 8, 5, or 2 Press back offs or Seated DB Press 3 sets of 8-12 Side Delt Raises – 50-100 reps in 5-10 sets, short rest intervals Close Grip Bench or Dips – 5 sets of 5-8 Tricep Extensions (1 or 2 variations ) 6-8 total sets of 8-15 reps Friday: Lats / Upper Back Chins or Pull Ups – ~50 total reps in as few sets as possible Pulldowns (different grip than exercise one) 3-5 x 10-12 Barbell Rows (or other row variation) 3-6 x 8-12 Rear Delt Rows or Face Pulls 5 x 10-15 Shrugs 3 x 15-20 Saturday: Squats + Quads/Abs/Calves Squats – 3 work sets of 8, 5, or 2 Hack Squat or Leg Press – 3 work sets of 10-20 Weighted Step Ups – 3 sets of 10 per leg Abs/Calves – whatever Obviously you don’t have to follow this routine exactly if you aren’t into the bodybuilding aspect of it. For instance, many clients will forgo all the quad assistance stuff and simply Squat and then go drag a sled or push a prowler. Fine by me. Modify how you like, but you get the point. Still train each lift heavy 1x/week but allow yourself to experiment with new exercises, train with some higher rep ranges, and have a little fun. You might even surprise yourself with some new PRs. We’ve been using this formula in my online training club The Baker Barbell Club for the past several months and my guys are setting PRs left and right. September / October – November: Strength Peak #2 Now the fun stuff is over it’s time to get back to work with more regular exposure to the barbell exercises for a second strength peak of the year. How you choose to do this up to you. but I suggest you select programming that increases the frequency and per session volume of the “contested” lifts, cuts down on the volume of the assistance work, and increases the average weekly intensity across the board. This might mean a second run of the Texas Method if it worked for you back in the Spring. Set some conservative PR goals for your lifts and set those up towards the last week of November. Maybe the week prior to Thanksgiving if you plan on traveling during that holiday. From there, work backwards through the month of November and October to set up your training cycle. Weigh those numbers against the numbers you ended your summer split routine with to make sure you aren’t dramatically over-estimating your strength or under estimating your strength. Or you can use a different type of peaking program such as my KSC Method for Raw Power Lifting / Strength Lifting which uses a Volume / Intensity approach but is organized differently than the Texas Method. There are obviously a number of other peaking type programs you can use here. December (Deload + GPP) Sometime in late November or early December you will have hopefully hit some new numbers for the year and ended things on a positive note. How you handle December is up to you. I know around my gym, attendance starts to drop in mid-December as people begin to travel and more or less focus on family activities and closing out the year at work. Mentally, a lot of people just kinda use this time of year to relax and recharge. I’m a supporter of this actually, and if you are busy with lots of family activities and travel it can make some sense to use this time of year as a prolonged deload or what some people call “strategic deconditioning.” I don’t necessarily mean that you just cease all training. But you can back off quite a bit. If you lose a little bit of strength, it’s not really the end of the world. It’s hard to hold a “peak” all year long and strength comes back relatively quickly when you start hitting the weights hard again in January. 3-4 weeks of easy training is good for the body and soul. You can heal up some of your aches and pains, relax from the pressure of climbing under the heavy squat bar week in and week out and relax your nutritional habits a bit. I’d still try and get into the gym 2-4 days per week, but do what you feel like doing, more or less. I often use this time of year on myself to go light for 2-3 weeks and I wind up doing a lot of body weight type training and a lot of cardio interval stuff. I find that these types of workouts which dare I say are “Crossfittish” in nature (although I don’t kill myself with volume) keep me from getting ridiculously fat during the Holidays and keep my conditioning from dropping off so much that the month of January is hell on soreness. I’ll often do a routine that looks like this: Monday: Bench Press – work up to set of 5ish, then Bench Press or Press x 10 or Push Ups x 50 + 500m Rower for 3 rounds Tuesday: Squat – work up to set of 5ish, then Incline Treadmill or Sled for 20 minutes Thursday: Press – work up to set of 5ish, then Dips + Chin supersets Friday: Deadlift – work up to set of 5ish, then Deadlift x 10 + 500m Rower for 3 rounds Saturday: AirDyne Bike for 30 minutes For the heavy sets I usually just pick an arbitrary weight that is an even plate arrangement (225, 315, 405, etc) somewhere in the range of what would be a moderately heavy set of 5. Sometimes I do a little more or less. Again, I kinda go by feel and don’t focus on trying to go exceedingly heavy, just get a little work in for a single set so my strength stays in the ballpark. I like leaving them gym on these days feeling good and energized, not exhausted and beat to hell. You obviously don’t have to do this routine exactly. It’s not a prescription for anyone. Just an idea of how you might approach the last several weeks of the year. Give yourself a break from heavy, high volume barbell work, go easy but stay in shape. Do something you don’t ordinarily do and don’t spend more than 45-60 minutes in the gym. Client John Petrizzo – Case Study, Part 1 In 2012 I was contacted by fellow Starting Strength Coach John Petrizzo for consultation regarding his training. John is a very bright guy. He is on the Starting Strength Coaches Association’s Science Committee and is Physical Therapist by trade. John knows his stuff about training and is an excellent strength coach himself. But he is also sharp enough to recognize the fact that even coaches need coaches. We all suffer (to varying degrees) with the inability to objectively analyze ourselves. We are all plagued by our own biases about training, and we find ways to talk ourselves into doing the things that we want to do, or talk ourselves out of the things that we don’t want to do – regardless of what will actually bring us closer to reaching our goals. So John contacted me to get some objective analysis of how to move forward with his programming. All of us that have spent any significant time under the bar, have dealt with the dreaded “paralysis by analysis” when it comes to our programming. There are a lot of options out there to choose from, and quite frankly, World records have been set with all types of different strength programs. It can be difficult to hash out the correct path forward. One of the most difficult crossroads to navigate is the transition to intermediate level training from simple novice linear progression. John had hit a wall on his linear progression (using the basic Starting Strength program) and there was a wide variety of possibilities for him to explore for his intermediate level training. The most common transition into intermediate programming is the Texas Method, however I didn’t think that was the direction for him. His work schedule was too demanding to accommodate the length and rigor of the workouts and he was strong enough that I felt like he might burn out pretty quick on that format. I told him that the next phase of programming should keep two goals in mind: 1) Short and focused workouts 2) Get away from doing strictly sets of five One of the biggest mistakes I see with those who have used the Starting Strength program is the insistence to try and stick with sets of 5 forever, once they become intermediate trainees. Think about the Starting Strength novice program……basically all you do is sets of 5. Mentally and physically you need a break from the monotony. Myself and fellow Starting Strength Coach Matt Reynolds have had numerous discussions about how well trainees respond to lower volume higher intensity training after their initial run on the Starting Strength program. You are ripe to get some big gains out of less volume. Also, an overlooked part of the switch to less volume is the MENTAL BREAK that you get from knowing that you really only have to hit ONE thing hard when you get to the gym each day. I work long hours, similar to John, and I know that I could not train effectively if I had to Squat/Press/Pull at every session. Shorter, more focused gym time is critical for many busy professionals, especially after 30. Most trainees love this aspect of the program. It is sustainable over the long term and it will keep your enthusiasm up for training. There are basically four workouts: 1 – Squat 2 – Bench 3 – Deadlift 4 – Press You can plug those into a four day training week, like: Mon/Tues/Thurs/Fri (or whatever arrangement works for you) ………Or…….. You can rotate those four workouts over a Mon/Wed/Fri schedule. The latter can be good because it gives your body 4 unique training loads over the course of the month. In other words, over a 4 week training period, every week is a little different in the stress placed on your body. This makes stagnation and overtraining easier to avoid. Here is what a month would look like, using a 3 day schedule: Mon – Squat Wed – Bench Fri – Deadlift Mon – Press Weds – Squat Fri – Bench Mon – Deadlift Weds – Press Fri – Squat Mon – Bench Weds – Deadlift Fri – Press The first thing people usually do is freak out over the lack of squatting volume. Simple solution: Do a light to medium squat workout prior to deadlifting. You will be fine. Sets & Reps? Start your training program off with a weight that is 5 lbs heavier than your last 3×5 workout on your linear progression. So if your last squat workout on the LP is 395x5x3, then your first day on this program would start at 400. Do a set of max reps with 400 lbs, capping yourself off at 8. The next time you squat you will do 405 x max reps also capping yourself at 8. You will keep adding 5 lbs per workout and capping yourself off at 8 reps for as long as you can. As the weeks go by, your rep total will of course drop…….just add 5 lbs per week until you hit a heavy triple. At that point, reset the weight back to about 410-420 and start the progression over again….eventually aiming to beat all your previous rep maxes and winding up with a triple that is 5-20 lbs heavier than the previous cycle. You will follow this same protocol of doing rep work between 3-8 reps for all four lifts. Keep in mind, there is no set time frame for completing a cycle from 8 to 3. It may take you 20 weeks to get there, it may take 6. It doesn’t matter really, as long as you are beating rep maxes and winding up with a triple that is a little higher than the previous cycle. Back off sets To keep the volume up you may decide to include 1-2 back off sets of 10-12 reps after the main heavy set. Most will find they like doing this on the bench and the press and can live without it on the squat and deadlift. My buddy John Sheaffer of StrengthVillain.com calls this strategy “pushing up the back end.” This is just using higher rep back off sets to build volume. If you employ back off sets for the squat and deadlift, you won’t need more than 1 set in all likelihood. Jim Wendler’s Boring But Big Template in his 531 program operates off this same mechanism, but I tend to recommend a little less volume for the back off work than Jim does. Alternate Exercises As a way to add variety and keep from stagnating you might find that after a while you start introducing some alternate movements into the program. You can use them for the main lift itself, or for back off sets. For the deadlift, I like using 2 sets of Stiff leg Deadlifts on a raised platform for my back off work. Additionally, every 2nd or 3rd training cycle you can try subbing deadlifts with Deficit Deadlifts, standing on a 2-4 inch platform. For Bench Pressing you may try Inclines for your back off work or your main exercise. DB Bench presses also work well for the back off sets. Squats and Presses tend to do better when you just train those two lifts. Subs for them tend not to work as well. Assistance movements Chins/Pull Ups I have had success doing them as the second movement on Bench & Press day or as the 1st movement on the Squat/Deadlift day. For some of my MMA guys I put a big priority on chins and we do them when fresh before our leg stuff. The choice is up to you. I’d try to do one or the other twice per week. Triceps Consistent improvement on a 3-4 different tricep exercises is a good way to keep your bench and especially your press moving up. Do 2-5 sets of 8-12 reps after your Bench/Press sessions. Lying Tri Extensions, Dips, Pushdowns, Overhead Tri Extensions etc are all cool. Close grips benches can also be used as your back off sets after your main bench set. A lot of people who are used to training with the Starting Strength program don’t think this is enough volume. For some it may not be. And this program is not a universal recommendation for all intermediates. I felt like this program was appropriate for John, due to the fact that he is handling some pretty big weights and has a very demanding professional life. Factors like this can’t be ignored, they do have an impact on training. Brutal full body routines will just be too draining. You can do it for a few months here and there, but the goal (as John had stated to me) was to get a program that he could stick to for a long time and train with consistently. This program will allow that. If you get interrupted by work or illness and miss some days, you just pick up where you left off. It’s a simple program to manipulate. This was essentially a glimpse into what I recommended to John as his go to intermediate program when he wasn’t prepping for a meet. For lack of a better term, it is an “offseason” program. In part II, we will examine how we altered his training to prepare him for power lifting competition. Using the meet prep cycles I laid out for him, John added 210 lbs to his total in about 1 year. Client John Petrizzo – Case Study, (Power Lifting), Part 2 Overview In part I of this case study we looked at the “offseason” program of power lifter and strength coach John Petrizzo. In part II we will look at his meet prep program for the RPS Long Island Heat Wave in July 2013. There are several important changes we made to his program for the meet prep. First, we added much more volume in on the competition lifts. Instead of just hitting one top set to failure (or close to it) we changed to a sets across format. Adding in the higher volume work (5×5 in this case) allows the lifter to get in more practice with the competition lifts, and allows some fatigue to accumulate over the course of the loading period, which makes the tapering period even more effective. The second big change we made was the institution of a “mock meet” day on Saturdays. Power lifting is a sport and like all sports, it places a “sport specifc” demand on the body. The mock meet is nothing more than a workout that includes lots of singles on the squat, bench, and deadlift. Training the squat, bench, and deadlift on their own training days is fine, but it is not uncommon to see lifters who do this gas at meets. Especially when they get to the deadlift. If the lifter is always used to doing deadlifts first in the workout, on their own day, he may be in for quite a surprise when meet day rolls around and he is pulling his deads on tired achy legs. The mock meet does an excellent job of conditioning the body to go heavy on all 3 lifts in the same session. The mock meet was intentionally placed on Saturday to get his body in tune with lifting on a Saturday morning. I encourage all lifters to do this if they are able, especially if you are used to working out in the evenings. Our body has a way of setting its ‘clock’ to do certain things at certain times. Lifting heavy in the morning may not go so well if you aren’t used to it. Training Schedule The training schedule we set up for John was very simple: Tuesday: Squat Volume (5×5) Wednesday: Bench Volume (5×5) Saturday: Mock Meet Keeping in mind that John is limited on time with his career demands, and is a pretty strong guy, he wasn’t required to do anything other than squat on Tuesdays. It doesn’t seem like that much on paper, but 5 work sets of squats with 8-10 minutes of rest between sets can easily take 60-90 minutes, especially if you are slow to warm up (like me!). If one wanted to add in assistance work to this day, things like ab work, back extensions, reverse hypers, etc could all be performed although I’m not convinced they help all that much. If you wanted to be a bit more aggressive with your selection of assistance exercises then movements like goodmornings or power cleans are good choices. As you will see in just a bit though, we did John’s pulling volume at the end of his mock meet sessions. On Wednesday’s Bench Presses were also trained with 5×5 across with long rest periods. Bench Presses are not as fatiguing as squats, nor are they as complete an exercise, so I generally like to include standing overhead presses as an assistance lift on this day. Done strictly, this is an excellent movement to strengthen the shoulders (and keep them healthy), the upper chest, and the all-important triceps. 2-3 sets of 5-8 reps is appropriate when trained after the volume Bench Presses. John didn’t do any more than this, but certainly some additional tricep work could be added. However, it is important to remember that in 72 hours, the bench will be trained again for heavy singles, so we want to avoid creating excessive soreness and fatigue that will hinder progress on Saturday. Saturday’s mock meet trains the Squat and the Bench Press for 5 singles across, and the Deadlift works up to just one heavy set. At the beginning of the cycle we had John pulling his target weights for 3-5 reps. Over the course of 7 weeks, we lowered his target reps to 23 and eventually to 1-2. We have the option after the deadlifts to pull 1-2 sets of Stiff Leg Deadlifts for sets of 5. The back off sets are an easy way to accumulate some pulling volume without having to pull from the floor twice per week. The choice to do the extra deadlifting volume is an individual one that varies from lifter to lifter. John puts a TON of focus and intensity into his deadlifting sets (and therefore a TON of fatigue) and I’m not sure that he actually did the back off work on most weeks. Tapering After six weeks on the following schedule, it was time to taper down for Meet day, which was set to occur at the end of week 8. I have a very specific deloading/tapering plan that I use for intermediate/advanced lifters prior to a power lifting meet, that starts approximately 10 days out from the meet. Here is the basic template that I used for John: Week 6: Tuesday: Volume Squat Wednesday: Volume Bench + Assistance Saturday: Mock Meet (Last heavy day of singles) Week 7: Tuesday: Volume Squat (last volume day – hit new 5×5 PR) Wednesday: Volume Bench (last volume day – hit new 5×5 PR) + Assistance Saturday: Mock Meet (work up to openers only, approximately 90% of last week) *Mimic meet conditions as much as possible. Use commands, etc Week 8: Tuesday or Wednesday: Squat 3x2x80%; Bench 3x2x80% Saturday: Meet Day Notes Below (in quotes) are a few random excerpts directly from the documents that I sent over to John after our consultation: “Try and stay with 5×5 as long as possible. If you can’t make all 5 sets across in the latter weeks then you can just do like 1 set of 5 with the target weight and then back off about 5% and do the latter 4 sets with a slightly lighter weight. It is important that we keep the volume up though. You will reap the rewards during out deload at the end of week 7. Ditto with the 5 singles across. Make the sets across for as many weeks as possible, then just make your target single and back off 5% and do your last 4 sets with lighter weight.” On the Bench Press plan: “These numbers will probably seem very easy in the first few weeks. One thing you can do to make things harder is do everything with as close a grip as you can. As the weeks go by you can start sliding your grip out. This is a way to “make a light weight feel heavy” and it has been shown over and over again that doing close grip work has tremendous carryover to the heavy stuff. You can do this on the 5×5 work and the singles.” Results John totaled 1460 at the RPS Long Island Heatwave in July. Almost exactly 1 year before he totaled 1250 at the RPS Long Island Insurrextion. 210 lbs in one year! How to Cycle Training Volume (Example Programming Model) One of the most difficult tasks for an intermediate or advanced lifter is the management of training volume. We all know that to varying degrees volume is a necessary component of continued progression on the barbell lifts. We also know that a lot of volume is difficult to recover from. There are a myriad of factors that play into how we handle training volume including age, gender, level of training advancement, absolute strength (do we squat 300 or 600?), and our level of General Physical Preparedness (i.e. our fitness – Are you in shape to train?). Typically lifters will try to progress their volume work in a somewhat linear fashion. So if volume squats are on Monday for 5x5x315, then the following week we do 5x5x320, and the week after that is 5x5x325 and so on and so forth. This simple approach works pretty well for new intermediate lifters as it’s just about as simple as novice programming. But of course we all know that this method can’t go on forever and so lifters often have to “reset” their volume day loads every 6-12 weeks to keep from burning out and regressing. As a lifter grows in strength and in his ability to create stress, more fluctuation in the nature of the training stress is usually warranted. This is where a 3-week volume cycle becomes very very useful. As a general rule of thumb I like to keep volume work between 75-85% of 1RM and total workload between 15-30 total reps, although certain lifts might benefit from a little less or a little more. In addition, volume work set/rep schemes can also be “auto-regulated” a bit depending on the lift and the physical state of the lifter on a given day. In other words, if the goal is ~25 reps at 75% of 1RM, then 5×5, 4×6, 6×4, or 8×3 all might be suitable for that day. 5×5 is always a good go to set/rep scheme, but what if the lifter is feeling exceedingly strong on that day? Perhaps he can shorten the workout a bit by eliminating a set and just doing 4×6. What if he’s off just a bit and can’t manage that 5th rep on his sets….6×4 would be fine. What if he wants to keep rest time down and focus on explosive bar speed…..8×3 will allow for that, or even borrow from Westside and hit a session of 12 doubles on a 60-90 second clock. In fact, the system that I use is heavily influenced by what Louie Simmons of Westside Barbell advocates. According to Louie’s writings (which can at times be all over the map in terms of specific recommendations) he advocates a 3-week wave that looks like this for Squat Volume: Week 1: 12 x 2 @ 50% 1RM Week 2: 10-12 x 2 @ 55% 1RM Week 3: 8-10 x 2 @ 60% 1RM Of course, Louie’s lifters are mainly training for geared power lifting so bands are added to these percentages making them actually quite a bit more than 50-60% of 1RM at the top of the movement. At Westside they also use a variety of specialty bars, boxes, and all sorts of other equipment that make his exact programming model totally unnecessary and overlycomplicated for 90% of the audience that is reading this article. But we can certainly borrow this concept from one of the strongest gyms in existence and apply the fundamental concept to an intermediate Raw Lifter. The first thing to square away is that for your volume lifts you don’t need boxes, bands, chains, or specialty bars. I am not opposed to those things in general, but I reserve them mainly for assistance work and/or variations to use on a max effort day, since you can’t really max out every week on the primary lifts (squat, deads, press, bench). Volume Day is the day where we want to really grease the groove of our focus lifts and practice our technique, so practice the volume days without altering your mechanics with specialized equipment or varying the mechanics of the lift. Second, for building muscle mass, I’m a fan of keeping volume day reps in the 3-6 range. I’m not opposed to Dynamic Effort work, but I don’t rely on it exclusively for volume days for a prolonged period of time. In PPST3, there is an example program of how to work Dynamic Effort training into a cycle if you are interested. All that being said, lets look at how we might set up a 3-week Volume Cycle for a raw lifter. Week 1: 75% of 1RM – Goal of ~30 reps. In general I like to use 5 sets of 6 reps. If you are used to doing just 5×5, that added rep on each set will be quite noticeable. It makes the workout quite a bit harder, but most can handle it at this intensity which is fairly low. You’ll find this easier on Bench/Press and harder on Squats but it’s manageable and it creates a pretty high “stepping off point” for week 2, so you can actually notice (and appreciate!) the drop in volume. If it’s too much then 5×5 is fine. Week 2: 80% of 1RM – Goal of 25 reps. To me this is the meat and potatoes week where higher intensity / higher volume really intersect. Most of the time we’re aiming for 5×5, but if you have a little less energy, 6×4 also works. Admittedly we don’t do much 4×6 or 8×3 work on this day, but you can experiment. Week 3: 85% of 1RM – Goal of 15-20 reps. This week tends to have the most variability in terms of performance. Generally we are working in sets of 3-4 reps per set. So 4-5 sets of 4 work well or 5-6 sets of 3. Again, this is influenced by both the lift and the lifter, their absolute strength and level of fitness. How to progress….. Since this is a percentage based approach you can obviously just reset your %’s every time you hit a new max single on a lift. For an intermediate lifter you can hit a new heavy single every 4 weeks and re-adjust your %s based on your performance. Or you can simply add small amounts of weight each time you come through the cycle. So 2 cycles might look like this for a lifter with a 500 lb Squat: Week 1: 5×6@375 Week 2: 5×5@400 Week 3: 5×4 or 6×3 @425 Week 4: 5×6@380-385 Week 5: 5×5@405-410 Week 6: 5×4 or 6×3 @ 430-435 On Heavy Squat days where you aren’t training volume you should be hitting lifts at or above 90% of 1RM on the main lift or a close variant of the lift such as a box squat, front squat, pin squat, specialty bar squat, etc. This will help preserve your ability to strain against maximal loads which is a skill set that much be practiced with some degree of frequency if you want to lift big weights. There are lots and lots of ways to integrate this into a training program depending on how you have things set up. The following is how I have things set up in my Online Coaching Club. I’m using just the Squat and Deadlift as an example. I set things up on an 8-week cycle which creates a manageable amount of frequency for the lifters in my club, most of whom are over 30, and many of whom are well over 40. Week 1: Monday: Deadlift Intensity Friday: Squat Intensity Week 2: Weds: Deadlift Volume (75%) Week 3: Mon: Squat Volume (75%) Friday: Deadlift Intensity Week 4: Weds: Squat Intensity Week 5: Monday: Deadlift Volume (80%) Friday: Squat Volume (80%) Week 6: Weds: Deadlift Intensity Week 7: Monday: Squat Intensity Friday: Deadlift Volume (85%) Week 8: Wednesday: Squat Volume (85%) Week 9: Repeat Cycle This system creates an environment where lifters can train “all out” on volume and intensity days and performance is rarely compromised due to an overload of frequency, which is, in my opinion, what overtrains most 30+ lifters the fastest. One other thing we do though is place a Light Squat or Squat Variation on most every deadlift day for a medium amount of volume and intensity so that the lift doesn’t detrain. I also place a Deadlift variation (stiff legs, snatch grip, etc) on most squat days, also at a moderate volume/intensity to preserve performance on that lift as well. This means that lifters will perform high-stress Squat and Deadlift workouts 3 times every 2 weeks with a continuous fluctuation in the exact nature of that stress. In my opinion this is probably the number one way to avoid stagnation in your lifting without continual resets or switching to a new program every few months. Strategy: Rotating Rep Ranges The following article was based off of a coaching call I did with one of my clients, John, just last night. John is a strong late intermediate trainee who has built a 500+ Squat, 600+ Deadlift, and a 350 Bench Press. In the past, John has made significant progress with very basic intermediate level programming. His best gains have traditionally come through a tapering type approach that has him starting a program at a low intensity/high volume and linearly working down into a high intensity/low volume phase. This approach is reminiscent of many great Powerlifters, both past and current. Generally speaking we are talking about starting a training cycle with sets of 8 and working down the reps until we arrived at a max double or triple and then possibly hitting a max single at a meet. John’s best runs have occurred when the journey from 8s to singles was “unscripted.” In other words, we never really planned out when we would drop from 8 to 7 to 6 to 5, etc. We just started with sets of 8 and ran them as long as we possibly could until the weight on the bar forced us to drop down to 7 or 6. Then we would run that as long as possible until we were forced to drop to 5s and 4s. John had some amazing runs on this type of simplistic programming. But based off our conversation from last night, we both came to the same conclusion that John may be “done” with this type of programming. Although we have tried to duplicate this process several times since his first few initial successes, it seems that his body has become unresponsive to this methodology and changes need to be made. After his next meet, John will begin a cyclical approach to his training. This is an approach that I have used with dozens of trainees, both at the gym and with my consulting clients. Examples of cyclical training can be found everywhere in the strength training literature….I most certainly did not invent the concept. In Practical Programming for Strength Training many of the intermediate programs we wrote rely on cyclical training or a rotation in rep ranges week to week. Westside programming calls for new Max Effort exercises to be cycled in every week, and the Dynamic Effort Squat cycle follows a 3 week rotation. The ever popular 531 program designed by Jim Wendler is another example of a cyclical programming that has worked for a lot of people. I have lots of clients that operate off of a cycle of 5s, 3s, and 1s. I don’t do my programming the same way Jim does though – training maxes, AMRAP-ing the final set, etc is generally not part of my strategy. And with most early intermediate trainees I use a “sets across” approach to the 5s, 3s, and 1s – anywhere from 3 to 5 sets across at the specified rep range. I have found the reason that many trainees don’t respond well to Wendler’s 531 is due to the lack of training volume at the actual working percentage. The “one all out set” approach works extremely well for many, but most early intermediates require a little more training stress to drive adaptation. An example progression might be: Week 1: 3-5×5 Week 2: 3-5×3 Week 3: 3-5×1 Week 4: Deload or Repeat cycle The rotation doesn’t have to be 5s, 3s, and 1s. Sometimes when a client gets stuck in a 5,3,1 rotation I make a very very minor change to their programming – I switch them to 6s, 4s, and 2s. This doesn’t seem like much, but I think the power of this adjustment comes from turning the singles into doubles. For instance, if a trainee got stuck at 5x1x495, I’ll back them off a bit and try working up to 2-3x2x495 after a few cycles. This has a powerful effect. Even though total volume is about the same, the effect is different. With John, we are going to spread the rep range out a bit more. In the past, he has seemed to respond well to sets of 8. We both agree that 5s are an essential rep range to train in, so those will be included too. For the heavy neural work, we will use doubles instead of singles. This gives us the ability to avoid early burn out and drop to singles later once the doubles get stuck. So his rotation will be a 3 week wave of 8s, 5s, and 2s. This gives us work in the entire spectrum of strength producing reps. Mentally and physically, this weekly fluctuation is important. 3 different workouts gives us enough variety to keep things fresh, but we never get detrained in any one area. With the linear approach, John would always be a little detrained in one area or another. Working his 8s for too long was excellent for work capacity and growth, but he lost the sensation of the very heavy weight in his hands or on his back – something a strong lifter needs to do fairly regularly. Training too long for triples and doubles meant he was losing some of his work capacity and risking the “burnout” effect that heavy training can cause when done too often. The exact volume of a routine like this will vary from lifter to lifter. John has always been a kind of “one and done” lifter. His best progress has come when we focused on just one all out work set, followed by 1-3 back off sets depending on the exact exercise. Other lifters can still use this approach, but work sets could be done “across” for more training stress. Why the 8-5-2 Program Works (In a Nutshell) The following (in italics) is an excerpt from a Facebook Exchange we had last week in the private group for the Baker Barbell Club Online. We have been running variations of my 8-5-2 program in the online barbell club for several months and many of the members, old and new, are surprised about the regularity of new PRs being set by members on a regular basis on the Squat, Bench, Press, and Deadlift. The original question from one of my members was: Andy Baker et al, have you written (and for the rest, have you read) an article that gives a simple explanation of why 8-5-2 works? Or, is there a post you can point me to just to satisfy my curiosity. I have a copy of PPST3, and I don’t see anything similar in the intermediate section (though I confess I have not read the entirety). My Response is Below: Stephen and Mark are both correct. As an intermediate it’s not just that you need more or less volume / intensity etc, but also that you need to vary the TYPE of stress you are exposed to regularly. Sets of 5 work so well because they are right in the “metabolic middle”. In other words, multiple sets of 5 are heavy enough that they actually improve force production, but have enough work (or time under tension if you want to go there) to deliver some hypertrophy and endurance adaptations as well. Perfect for a novice to do JUST that. However at some point you can’t just keep doing 5s and expect to keep progressing. How do we improve the hypertrophy/endurance component and how do we improve the force production component? Well…..if you drive up your 8s you get more of the hypertrophy/endurance thing, if you drive up your 2s you get better at force production i.e. handling heavier weights. 2s are good because they don’t burn out our CNS like regular singles do and they allow a small amount of wiggle room to miss or have a bad workout and still hopefully come up with a few singles instead of just complete failure. Same with 8s. You can miss on occasion and still get 6 or 7 good reps – still building strength. The 3 rep ranges are far enough apart from each other that the loads each week vary quite a bit, but are all in the “strength building zone” I have programs that cycle between 5s, 3s, and 1s and that works too but not for prolonged periods of time. Before you know it your 5s, 3s, and 1s are all kinda “clustering” around similar loads and this makes stalling/burning out easier. Having wider gaps between loading each week prevents physical AND mental burnout in my opinion. The 3 week cycle means that you are hitting each rep range frequently enough so you don’t lose the adaptations you are gaining from each one. If you do say a 4 week block of 8s, a 4 week block of 5s, and a 4 week block of 2s then you are potentially detraining from the adaptations you aren’t working. Louie Simmons recognized and solved this detraining and stagnation problem with his Westside System which is a concurrent periodization model which trains all these facets simultaneously each week. Force production is trained EVERY WEEK with a max effort day (although exercises vary every week which is the conjugate method), Power is trained every week with a dynamic effort day, and hypertrophy / endurance is trained every week with a high volume of high rep “special exercises” i.e. assistance work. ” In a nutshell, the 8-5-2 program operates in 3-week cycles where each week is either focused on new PRs in sets of 8, sets of 5, or sets of 2. It’s not revolutionary or complex, but it does work. And we use this core strategy in split training routines, heavy-light routines, and heavy-light-medium routines. This is basic intermediate cycling. There is an emphasis on weekly PRs, although the target rep range changes each week. This fluctuation week to week keeps trainees progressing, but prevents premature burnout and stagnation. Alternating Rung Method The manipulation of sets, reps, and weight increments is probably one of the most confusing and tedious aspects of effective programming for strength training. However, as I often tell my clients “the devil is in the details.” This is one of the great challenges of programming. And the devilish details are the subject of this article. Arranging the weekly schedule and the order of exercises is fairly easy. This is in part due to the fact that there are only a handful of arrangements that actually work well. Unless you adhere to the old Weider “muscle confusion” principle, there are not an infinite amount of exercises to choose from that all work with equal effectiveness. It’s quite easy to stratify exercises in terms of their effectiveness, and that stratification easily determines the level of attention and priority they receive in the weekly schedule and in each individual workout. Where the rubber meets the road in programming is how we manipulate volume and intensity (determined by sets/reps/weight/frequency) from day to day, week to week, or month to month. This is the tricky part because it tends to be so highly individual and the same formulas do not apply to every lifter or every lift. Another challenging aspect of programming is rate of progression. In other words how much should each lifter add to the bar each workout? Or should they even add weight at all? Is it better in some circumstances to say, keep the weight on the bar the same but increase reps? Or add a set? Should you add weight but drop the reps? If you drop the reps should you add more weight than normal? How often should I drop the reps? If I drop the rep range down, when do I go back up again? There are other questions that pop up as well, but these are particularly frequent. One method I have come to rely on heavily with my clients is what I call the Alternating Rung Method of progression. This system involves weekly progression so technically this qualifies as intermediate level programming – although the nature of the progression is not as straight forward as many of my clients are used to, and many view it as slower than what they might like. The argument is that this methodology is steady. It tends to produce far fewer and less frequent stalls, and in the long run this saves time. Conservative yes. But I’d rather have a year of conservative progress than 6 month of aggressive progress followed by another 6 months fumbling around in the dark trying to replicate the previous 6 months. Simple entry-level intermediate level programming involves adding weight to the bar once per week. For instance, someone following basic Texas Method style programming would focus their efforts on a weekly improvement of their 5RM strength on each of the main lifts. This means that once per week the objective is simply to add 2-5 lbs for 1 set of 5 reps on each of their main lifts. Simple. So why not just do that all the time? Unfortunately simple weekly progression does not stay simple for long. Within Practical Programming for Strength Training, we introduced 2 primary mechanisms for sustaining longer term weekly progression – “running it out” and “alternating rep ranges.” The Alternating Rung Method is a variation of “alternating rep ranges” as described in PPST3, with just a little bit more complexity. We’ll use The Squat as an example of how to set this up. What I like to have my clients do is start with heavy sets of 6-reps. Depending on exactly what type of program you are running, this could be a single set of 6, or multiple sets across. For our example, we will use just a single set of 6 reps for the sake of simplicity. On week 1, we will say that our hypothetical trainee does a set of 6 reps with 300 lbs. In week 2 the client will perform a set of 4 reps with 320 lbs (that’s a 20 lb increase for those of you who struggle with math). In week 3 the client will perform a set of 2 reps with 340 lbs – another 20 lb jump. In week 4 the client will increase the reps back to 5 and decrease the weight – 310 lbs for a set of 5 reps. Notice that the 5 rep set is right in the middle of what was done for a set of 6 and a set of 4. In week 5 the client will perform a set of 3 reps with 330 lbs. In week 6 the client performs a heavy single with 350. In week 7 the cycle starts over again at sets of 6. This time with 305×6. Just a little bit more than what you did for 6 reps last time. Below is a sample progression of 12 weeks’ worth of training. (We will refer to weeks 1-3 and weeks 4-6 as mini-cycles. We will refer to the entirety of weeks 1-6 (or 2 mini-cycles) as a mesocycle). Week 1: 300×6 Week 2: 320×4 Week 3: 340×2 Week 4: 310×5 Week 5: 330×3 Week 6: 350×1 Week 7: 305×6 Week 8: 325×4 Week 9: 345×2 Week 10: 315×5 Week 11: 335×3 Week 12: 355×1 In case you are confused, let me try to further clarify. In the above example we use increases of 20, 10, and 5 lbs at various points in the program. These are the Alternating Rungs. Twenty pound jumps are used within each 3-week mini-cycle: Between the 6s, 4s, and 2s. And then again between 5s, 3s, and 1s. Ten pound jumps are used between mini-cycles one (6-4-2) and mini-cycle two (5-3-1). So between 6 and 5 is a 10 lb increase. Between 4 and 3 is a 10 lb increase and between 2 and 1 is a 10 lb increase. Five pound weight increases are used to start a new 6 week mesocycle (642531 is a six-week cycle). Twenty, ten, and 5 lb weight increases are just an example for the Squat, for a lifter at this particular level of strength. A stronger lifter might use even bigger increments – especially on say, the deadlift. A weaker lifter, or someone applying this method to the Bench or the Press might use smaller increments. For instance, a hypothetical progression might go like this: Week 1: 100×6 Week 2: 110×4 Week 3: 120×2 Week 4: 105×5 Week 5: 115×3 Week 6: 125×1 Week 7: 102.5×6 Week 8: 112.5×4 Week 9: 122.5×2 Week 10: 107.5×5 Week 11: 117.5×3 Week 12: 127.5×1 In this instance the lifter uses 10 lb increments within a 3 week minicycle, 5 lb increments between 3 week minicycles, and 2.5 lb increments to start a new 6 week mesocycle for the Press. If you are confused about how to progress, when to progress, and you keep running into walls try introducing this style of programming into your training. This level of complexity is not necessary for early intermediate lifters. However, if you’ve been plugging away at weekly progression for more than a few months then this method might be just the thing that gets you unstuck. And the plus side is that it can keep you unstuck for many months with little to no changes to the programming. What is a Rotating Linear Progression? A rotating linear progression is a very very simple method to structure your training that has been around for many many decades. I’m certainly not taking credit for inventing it, but I do use this strategy at times with certain clients. The rotating linear progression is a method that tends to work best for later intermediate trainees who respond well to lower volume training. While I wouldn’t necessarily classify the method as “high intensity” it is certainly high in “intensiveness.” In the lifting world we tend to classify “high intensity” training as something that occurs when lifters are handling loads in excess of 90% of their 1-rep max. This is mostly going to be heavy training in the 1-3 rep range. In certain bodybuilding circles (as well as with the general population) high-intensity training is generally assumed to be anything where the lifter is exerting very high levels of effort. However, high levels of effort can be demonstrated at just about any rep range provided load is sufficient and sets are taken to or near failure. But if we want to be just a little bit more technical – this is better defined as intensiveness – just so we don’t get our terminology confused. The rotating linear progression is high in intensiveness, but not necessarily high intensity, although on occasion the lifter may enter into some higher intensity training (<90% of 1RM) whether it be purposeful or accidental. But in general, the way I use the rotating linear progression (RLP) is with a single all out set that results in a new PR for either weight or reps. If you stopped there (and some people do on occasion) this would be an exceedingly low volume program, but in general, volume will be accumulated during the remainder of the workout via back off sets and assistance exercises. How much volume is added to the rest of the workout will depend, by and large, on the goals and needs of each individual lifter. So what does an RLP look like in practice? Usually I try to select a load for the trainee that I know he can do for about 8 reps. Then after I warm him up, we get under the bar and try to squat that weight for 8 reps. If my load selection was right, then rep number 8 was a bit of a struggle, but there was no technical form breakdown. It was just a really hard set of 8. When we come back the following week, I’ll have him add 5 lbs to the bar and attempt to squat it for 7-8 reps again. If he gets 8, then the next week we go for 7-8 reps again. He may be able to add 5 lbs to the bar each week and hit a top set of 8 for say 3-4 weeks and eventually we’ll have to stop at 7. The following week we’d add 5 lbs to the bar and aim for a top set of 6-7. If possible we keep hitting sets of 7 for a few weeks while adding load to the bar. We’ll eventually drop down to 6 reps, and then 5 reps, and then 4 reps. We may spend several weeks at each rep range before dropping down (this is ideal!!). Once we cap out at a heavy set of 3 reps then we start the cycle over again at 8 reps. However, when we start over, we will renew the cycle with a top set of 8 that was equal to his last set of 7 from the previous cycle. Then we run the whole thing through again, trying to set rep PRs all along the way. So weights we squatted for 7s, we try and get for 8. Weights we hit for 5 reps in the previous cycle, we try and get for 6-7 reps in this cycle. Ultimately we want to end with our max effort triple heavier than where we ended the previous cycle. If you are able to set rep PRs all along the way (in the 4-8 range) on each subsequent cycle, and each cycle culminates with a heavier and heavier triple then you can consider the program to be working for you. If you are not regularly setting rep-PRs week to week (most weeks, not necessarily every single week) and your max triple is not ending any higher than it did on the previous cycle, then I would suggest that this is not the best programming strategy for you. Here is an example of multiple cycles of a RLP for you to get an idea of how this should work: Week 1: 300 x 8 Week 2: 305 x 8 Week 3: 310 x 8 Week 4: 315 x 7 Week 5: 320 x 7 Week 6: 325 x 6 Week 7: 330 x 6 Week 8: 335 x 6 Week 9: 340 x 5 Week 10: 345 x 5 Week 11: 350 x 4 Week 12: 355 x 4 Week 13: 360 x 4 Week 14: 365 x 3 (Don’t do another week of triples. Stop here and restart the cycle Week 15: 315 x 8 Week 16: 320 x 8 Week 17: 325 x 8 Week 18: 330 x 7 Week 19: 335 x 7 Week 20: 340 x 7 Week 21: 345 x 6 Week 22: 350 x 6 Week 23: 355 x 5 Week 24: 360 x 5 Week 25: 365 x 5 Week 26: 370 x 4 Week 28: 375 x 4 Week 29: 380 x 4 Week 30: 385 x 3 Restart at 330 x 8 There are a few keys to making a program like this work for you……. 1. You must put forth high amount of effort on your main work set every week. You don’t need to crash into the pins every week, but you should be damn near limit each week. If you don’t have the mental fortitude to push week in and week out, you won’t have success on this program. 2. This is not a high frequency program. Doing limit sets like this cannot be done on the same lift 2-3 days per week for an intermediate lifter. On squats for example I would recommend squatting on Monday for example with an RLP, and then later in the week (Thursday) you can apply this same approach with Deadlifts and then perhaps follow the deadlifts with some lighter squats or front squats. 3. Always come into the gym with a predetermined load and rep goal for the day. This makes a difference mentally. Saying to yourself “I am going to Squat 315 x 8” is more powerful than saying “I’m going to Squat 315 until it gets hard.” 4. Try and get at least 2-3 weeks at each rep range while increasing load before allowing yourself to drop a rep from the progression. In other words, try and hit 6s for 2-3 weeks before dropping to 5s. If you drop a rep every single week then you likely aren’t pushing hard enough each set to drive adaptation or you just aren’t responding to this approach 5. There is no set timeline for the RLP. It simply starts at 8 reps and whittles it’s way down to 3 reps over many weeks. If you are kicking ass in the gym and with your recovery and you spend 5 weeks hitting new 6-rep maxes, so be it, and it will extend your cycle out pretty long. That is a good thing. In my observation, the longer your cycles are lasting the stronger you are getting. You may have some cycles last longer than others. In fact this is almost always the case. Following your main work set you probably want to add some volume with 2-3 back off sets. The simplest way to do this is to simply strip about 10% off the bar (maybe up to 20% for deadlifts) and perform 2-3 sets of a rep range that is equal to or slightly higher than where your primary work set finished. So if you hit 365 x 6 then drop down to about 325 and hit 3 sets of 6-8 reps. If you do multiple back off sets like this, they should not be limit sets. You are just drilling down on some volume with submaximal loads. However, I have had a lot of past successes (personally and with clients) of performing just a single back off set, again taken to the limit. So instead of hitting 325 for 3 sets of 6-8, you’d just rep out with 325 and take it as far as you can, maybe even up to a set of 10-12. This is brutally hard but very effective. You can do a mix of both approaches depending on your preference. The 2 all out sets method was a favorite of my friend John Scheaffer of Greyskull Barbell. We talked several times about this approach and both had lots of professional and personal success with this approach. So again, if you respond to (or simply enjoy) high intensive and lower volume training, this approach can work for you. If you want to add a simple strength protocol on top of a bodybuilding protocol, this can work for you. Or if you are simply in a time crunch right now and don’t have time for long drawn out workouts you might be surprised at what an ass kicking 2 all out sets of squats can be, and how quickly you can get it done. Rotating Linear Progression – Meet Prep Question Q: Andy, your Rotating Linear Progression model of training is working well for me in prep for the United States Strengthlifting Federation Nationals in Jan. I’ve set up a 12 week cycle up to the meet on Sat 18 Jan, and the past 5 weeks have gone well, but I need some advice on how to program meet prep going forward. The 2 x week seems to be agreeing well with my old guy recovery. I’m doing the single AMRAP backoff set for both SQ and DL after the main work set, its a fucking killer, but like it. Here’s the weight, set and reps done so far: Week 1 Day 1 SQ 275x8, 245x12 (AMRAP 90% of workset) Day 2 DL 405x8, 175x15 in 30 sec (stupid AYF FB challenge) Week 2 Day 1 SQ 295x8, 265x11 (AMRAP 90% of workset) Day 2 DL 415x8, 335x12 (AMRAP 80% of workset) Week 3 Day 1 SQ 300x7, 270x12 (AMRAP 90% of workset) Day 2 DL 425x7, 340x12 (AMRAP 80% of workset) Week 4 (Thanksgiving week traveling VA Beach) Day 1 SQ 305x7, 275x10 (AMRAP 90% of workset) SLDL deficit 275 2x5 Day 2 missed Week 5 Day 1 SQ 310x7, 280x9 (AMRAP 90% of workset) Day 2 435x7, 350x12 (AMRAP 80% of workset) Monday and Thu are Day 1 & 2 of Week 6 coming up If I can I’ll be adding 5 lbs to SQ and DL weekly Week 6 6 reps Week 7 6 reps Week 8 5 reps Week 9 5 reps? Week 10 4 reps? Week 11 3 reps? Week 12 light sets (65% 1 RM), meet on Week 12 Sat How do you recommend I move forward weekly from here? Andy: what is the Squat goal for the meet? I might try walking this cycle backwards like Marty Gallagher used to do Reply: SQ goal is 380, 5 lbs over all time PR of 375 set at last meet end of Sep. DL goal is 500 Andy: 90% of 380 is 342 so if you can end the cycle at 345x3. You SHOULD be able to hit 380 x 1. I think you can go a bit more aggessively than that though…Let me know if you think this is possible 320 x 7, 330 x 6, 340 x 5, 350 x 4, 360 x 3, 370 x 2. You do that and 380 will fall. Very aggressive DL run up would be: 445 x 6, 455 x 5, 465 x 4, 475 x 3, 485 x 2-3, 495 x 2-3. 500+ x 1. Less aggressive: 445 x 6, 455 x 5, 460 x 4, 465 x 3, 470 x 2-3, 475 x 2-3, 500 x 1 Time Saving Techniques for Assistance Work Don’t let the title of the article fool you. This doesn’t necessarily mean that “saving time” through the use of these techniques makes these exercises any easier. In fact, it generally makes things harder. But the benefit you get is not just a shorter more efficient workout, but often times a more effective exercise. Minimizing time in the gym with the techniques I’m about to explain doesn’t necessarily reduce the amount of work you are going to do. It simply takes a similar workload and condenses it into a shorter time frame. Certainly if you are training for hypertrophy or increased work-capacity, this is a win-win. A short note of caution…..for most of these techniques, I don’t advocate using them with the big lifts (squat, bench, deadlift, press, etc). These techniques are best used with assistance exercises for smaller body parts, and most of the time they work best when using machines, dumbbells, your own bodyweight, or cables/bands. Super-Sets / Mini-Circuits One of the biggest mistakes lifters make is not resting enough between sets, particularly on the major barbell exercises. I can’t tell you how many times people have told me they rest just 2-3 minutes while performing their heavy 5×5 Squat workout. Sorry folks – for heavy strength work, that ain’t gonna get the job done. I almost always prescribe 5-10 minutes of complete rest between heavy sets across on the major barbell exercises. But that’s all at the front end of the workout, usually just on the first lift of the day. Once you get the heavy stuff out of the way, you might have a few assistance exercises you’d also like to complete with lighter weights in order to work on weak points, build muscle mass, or improve your GPP. Depending on how your training split is organized you can often group together 2-4 movements and perform them in a continuous circuit with minimal rests between exercises. I prefer to use this approach with exercises that don’t all work the same muscle group. Let’s take an example. In the programming I use for my online Barbell Club, every other Squat workout is a high volume squat workout. So in one of our upcoming workouts, we’ll start the session off with Squats for 5 sets of 6 reps at approximately 75% of 1RM. So my guys are gonna be pretty tired after this is done, and I wont’ have anything prescribed after that except for lighter lower body stuff for GPP (and I also usually put some back work on Squat/Deadlift days). So the workout might read like this: Primary Strength: Squat 5 x 6 x 75% of 1RM Assistance: Lat Pulldowns 3 x 10-12 Back Extensions 3 x 15 Weighted Decline Sit Ups 3 x 10 Standing Weighted Calf Raise 3 x 25 So….if we want to take the long way (and I mean really long way) then we will perform each exercise one at a time, one set at a time, and we’ll rest as much as we need between sets of each movement. But I think the better way to perform work like this is to either group the workload into 2 super sets or one giant circuit. In the former, I’d group together the Lat Pulldowns and the Back Extensions and do approximately 3 sets of each alternating back and forth between the two movements until all the work was done, and then I’d move onto the super sets of Sit Ups and Calf Raises. Again, with little to no rest between exercises. Since none of this work is heavily dependent on force production – it doesn’t matter if you are tired. Just push through and get the work done and you’ll build some conditioning and work capacity in the process. And you’ll have a much shorter workout. I’m not a terribly huge fan of super-setting exercises that overlap too much on the same muscle group. For instance, trying to super-set tricep pressdowns and dips. I just feel like one or both of the exercises has to get compromised so much in terms of load, that it makes it a non-ideal way to do things. However if you want to build some upper body GPP and save some time then it makes total sense to pair up things like Chin Ups and Dips together or maybe push ups with bodyweight rows on rings, or the ever popular bicep/tricep super set where we match up a curl variation with a tricep extension of some sort. Rest Pause Sets (My favorite!) Rest-Pause sets are essentially setting up a certain rep goal for each set and then hitting that total rep goal in a series of “sub-sets” with extremely short rest periods between them. Each subset will be taken to failure or near failure. Generally the rest time between sub-sets is like 10-20 seconds. I usually just count out like 10 deep breaths rather than use a timer. Then you would take a full 2-3 minute rest before you start your next rest-pause set. Let me give you an example: Let’s say you are going to do a Cable Tricep Pressdown for 3 sets of 20 reps, using the rest-pause technique. Generally I like to aim for at least half (or just a little more) of my reps on the first effort, and then hit my target goal with no more than 3 total subsets. So here is how it might look….11 reps x 100 lbs…rest 10 deep breaths…..5 reps x 100 lbs….rest 10 deep breaths…..4 reps x 100 lbs. Rest 2-3 minutes and start another rest-pause set of 20. This has an advantage over simply doing a set of 20. Primarily – load. To do a set of 20 reps without stopping requires extremely light weights, but just by breaking that set of 20 up with some very short rest periods, I am raising my average workload tremendously. Same volume, but more weight = more strength and more muscle mass. The way most people screw these up is going too heavy. If you aim for a total rep count of 20, and your first sub-set fails out at 4 you are in big trouble. You don’t want to do 8 sets of 2 all the way up to 20. That’s why I advocate getting 50-60% of your reps with that first effort and then limiting the total number of subsets to 3. One big chunk at first and then two smaller subsets and you should be at your goal. You should adjust the weight accordingly from set to set to make sure that this happens. Descending Sets & Drop Sets This is the perfect follow up to the rest-pause set explanation. Descending sets and drop sets both do the same thing. They lower the weight from set to set, thereby allowing you to shorten rest intervals between sets. The main differences between the two (and it’s big differences) are the (1) rest time (2) and the degree of the reduction in weight between sets. Let’s use a Seated Dumbbell Press as an example since I like this exercise and I like both these techniques applied to this exercise. Most commonly people use “straight sets” for this exercise. Let’s assume the goal is 4 sets of 8-12 reps. With straight sets the lifter would simply choose a weight that he can perform for 8-12 reps on all 4 sets with let’s say a 3 minute rest between sets. We’ll say he can do that with a pair of 65 lb dumbbells. The downside of this, is that in order to achieve all 4 sets of 8-12 reps on a 3 minute rest our lifter is probably using weight that isn’t really taxing him that much on the first set or two. If he did go all out on set 1 (when he’s the strongest) he’d empty his gas tank and fall out of his desired rep range….unless he added rest time. But remember the point of the article is to save time, not add time to our training sessions. With descending sets, our lifter would take a weight that causes him to fail out between 812 reps…the heaviest weight possible he can do with good form. Blow it out, go all in on this first work set while you are the strongest. Let’s say that weight is 75 lbs x 8. But now, since he’s gassed….let’s rest 2-3 minutes and drop down to 70s for another set. Maybe 8 or 9 this time. Another 2-3 minute rest and drop down to 65s for 9 or 10. Another 2-3 minute rest, drop down to 60s for 10-12. So basically the same protocol, but aggregate load was much higher than with straight sets and especially his top end set was much heavier. Drop sets are a little different. Drop sets generally only occur on the tail end of whatever exercise you are doing. They might follow a series of straight sets, a series of rest-pause sets, or even a series of descending sets. It’s a little exclamation point at the end of an exercise. If you are training for hypertrophy, it creates an incredible pump. Drop sets occur immediately following the last regular set of an exercise with little to no rest in between and because of that, there is generally a large drop in weight. So let’s say our lifter (from the previous example) ends his shoulder workout with 60 lb dumbbells for a set of 10. If he wants to do a drop set then he will rack the 60s immediately following his 10th rep and walk directly over to say…the 40s, and perform a set of max reps. He’d rack the 40s and immediately pick up a pair of say..25s. And rep those out as well. Then we’d say our lifter has performed 2 drop sets. There are no real rules as to how this is supposed to work in terms of reps, but I generally like to average about 10 additional reps per drop set. The goal with these is blood volume into the muscle, so it doesn’t make that much sense to do too many low rep drop sets. Timed Sets and Rep-Total Sets These are essentially two sides of the same coin. It’s essentially setting a pre-determined workload and then using time as measured variable and not just reps. So for a timed set, I might say something like “Barbell Curls for 3 minutes and 65 lbs.” And so the lifter does as many curls as he can in 3 minutes with a 65 lb bar and writes down his total reps achieved. Next time, we might do the same time and the same weight, but try and achieve more reps in that 3 minute period. Rep-Total sets are actually a lot like rest-pause sets. You’ll set a predetermined number of reps to achieve with a given weight and then hit that number in as many sets as it takes. Then you will time how long it takes to get there. Typically though, when I talk about rep-totals I talk about very high rep totals like 50-100, usually done in sub-sets of 10-20 reps at a time. I really like this for bodyweight stuff. So maybe we end an upper body workout with 100 push ups for time. And as an example our lifter does 35, 27, 19, 11, 8. He’d time how long it took him to do all that and then next time try and hit 100 in shorter time with perhaps less sets. Maybe next time he does 42, 31, 20, 7. Training on Imperfect Schedules - Part 1: Training Twice Per Week One of the issues I deal with regularly, both here at the gym as well as with my online clients, are schedules that don’t necessarily allow for the perfect training routine. It’s funny how our bosses, our businesses, our customers, and our families seemingly never “get on board” with our training schedules! The nerve! The reality is that a solid barbell based strength training program takes a lot of TIME to administer properly. For most novice and early intermediate trainees, the preferred schedule is the standard Mon-Weds-Fri routine, working the fully body at each session with 3 major barbell exercises and perhaps 1-2 assistance exercises with bodyweight, dumbbells, or machines. When I start with a new novice client the workouts in this format are generally pretty short and sweet. At their level of strength, they can move pretty fast through all the warm up and work sets because they haven’t yet developed the ability to severely tax their body yet with their work sets. Rest time can be kept down to 2-3 minutes and there aren’t a whole lot of warm up sets yet in the workout. To get through an entire full body workout of Squats, Presses, and Deadlifts may only take 40-45 minutes during the first couple of weeks if we aren’t messing around. As the client grows in strength however, there is the need for both additional rest time between work sets (now 5-8 minutes usually) and there is an increased number of warm up sets. The time drain isn’t limited to just the workout either. It’s the recovery time afterward. I don’t know about you, but when I get done with a heavy squat and deadlift session, my brain is no good in the immediate aftermath. Tack on a Prowler workout to the end of the lifting session and I’m toasted for at least an hour or so post workout. Nothing productive is likely to happen. Most people are looking at a minimum of 90 minutes to get through a heavy full body barbell based training session after their first few months of training. When you include drive time to and from the gym, showering/eating, and a built in buffer time for your brain to come back on-line, there is a serious challenge in getting in the preferred fully body workout 3 days per week. I’d say for the majority of 30+ working adults it’s a constant challenge to get everything in consistently. What I have generally found is that most clients can set aside the time for the longer workouts twice per week, but 3 times per week is a challenge when trying to balance the training time with their work and family lives. A lot of my online clients in particular tend to train once on the weekends (Saturday or Sunday) and then once during the week (often Wednesday), and find they can do so without having to rush through their workouts. The reality is that twice per week training works very well. At the gym, most of my clients train on either Mon/Thurs or Tues/Fri. These are the two preferred schedules as it balances out the workload evenly over the course of the week. Especially for my clients over 40 (and that number continues to grow) a twice weekly training schedule might actually be preferable to 3 days per week. A typical training week looks like this for a strength focused trainee: Day 1: Squat / Bench Press / Upper Back (Chin, Lat Pull, Row, etc) / Specialty Exercise (1 or 2)* Day 2: Squat / Press / Deadlift / Specialty Exercise (1 or 2)* (*Specialty exercises are individualized assistance exercises that we select for each clients’ weak point or perceived weak point. Often these exercises are for the triceps, biceps, the abs, extra lat/upper back work, or some sort of DB Press for added upper body mass). For clients that have been training a long time we switch up exercises more often, but we can stay within this solid basic template. It is almost universally applicable for novices and intermediates. Sets and Reps are completely dependent on each individual trainee, so I’m not going to go through all those details here. As a client progresses out of the novice and early intermediate strength focus, their attention often turns to physique – especially upper body development in the case of many male clients. Now that they are strong, they want to use that strength to build a better looking body. Here is how I have structured a twice weekly schedule for someone who wants to focus a little more on upper body development and physique and less on just pure strength: Monday: Squats + Chest / Delt / Tricep Thursday: Deadlifts + Back / Biceps An example week might look like this: Monday: Squats 1 x 3-8, 2-3 x 10-15 Bench Press 1 x 3-8, 2-3 x 8-12 Seated DB Press 3-4 x 8-12 Dips 3-4 x 10-15 Thursday: Pull Ups – 5 sets to failure Deadlifts 1 x 3-8, 2-3 x 8-12 Barbell Rows 3-4 x 8-12 Barbell Curls 3-4 x 10-12 I also have a “general” fitness template that I utilize for clients who have kind of graduated from pure strength training into something that challenges not just their strength, but their cardiovascular and muscular endurance. This is just an old-school “supersetting routine” but don’t be fooled, it is a bear to get through. This type of training tends to be very popular among my female clients, but many men enjoy this as well. It is quite literally a change of pace. Here is an example week: Day 1: Quads / Upper body Pull / Abs Squats + Chins or Assisted Chins – 5 sets each Weighted Step Up + Barbell Rows – 4 sets each Decline Sit Ups + Barbell Curls – 3 sets each Day 2: Post Chain / Upper body Push / Abs Deadlifts + Standing Overhead Press – 5 sets each KB Swings + Push Ups – 4 sets each Hanging or Lying Leg Raises + Lying Tricep Extensions – 3 sets each. Templates like this are great for general fitness trainees as they are almost infinitely customizable, allow for tons of variety, but still include the tried and true basics on a weekly basis. In part II, we’ll discuss ways in which we can organize training into shorter more frequent workouts, and how to best train while traveling. Training on Imperfect Schedules – Part 2 In Part 1 of this series we briefly went over a few training templates that work for people who can realistically only get in two full-fledged training sessions each week. For many of us 3 or 4 heavy barbell based strength workouts might be ideal, but the constraints of our careers and family lives simply prevent us from putting in that many serious gym days each week. For this type of client we generally set aside two days per week that are evenly spread out by 2-3 days of rest. Mon/Thurs, Tues/Fri, or Weds/Sat are set ups that work well. During these sessions clients will train the full-body with 3-4 compound exercises and maybe 1 or 2 assistance lifts to work on a perceived weak point. These types of workouts, if done right will usually average about 90 minutes in length. If you push the pace and focus you might be able to squeeze the session into an hour. If you like to take your time, talk to your gym buddies, or gaze at yourself in the mirror for extended periods of time, it might push 2 hours. Other clients that I work with, are really stretched for time each and every day of the week. Long office hours with a brutal commute on each end plus kids activities on the weekends mean that this client might do better with a shorter, more focused workout performed more frequently. In other words, this client has a really difficult time carving out 1-2 hours at any point during his or her work week. No problem. I have solutions for that too. In my early 20s, I was very focused on bodybuilding type training and one of the more effective routines I ever used was the old “one body part per day” routine. That type of routine is can be very effective for someone with really limited gym availability. In fact, you can narrow it down even further to just one lift per day if you are really pressed for time. Below is an example of how one might organize their training into a 5 or 6 day per week plan: Monday: Chest Tuesday: Back (upper back focus) Wednesday: Quads Thursday: Shoulders Friday: Arms Saturday: Hamstrings/Lower Back If thinking in terms of “body part” bothers you, then you can essentially accomplish the same thing by breaking it down into lifts. To keep things really really simple, do one primary lift for strength, and one secondary lift for hypertrophy. An example routine is below: Monday: Bench Press or Incline Bench Press 5 x 5; Dips 3 x 10-12 Tuesday: Weighted Pull Ups 5 x 5: One Arm DB Rows 3 x 10-12 or Barbell Rows 4 x 8; Lat Pulldowns 3 x 10-12 Wednesday: Squats 5 x 5; Leg Press 3 x 15-20 Thursday: Press 5 x 5; DB Press 3 x 10-12 Friday: Barbell Curl 4 x 8-12; Lying Extension 4 x 10-15 (you don’t really need a strength lift for direct arm work) Saturday: Deadlifts 2 x 5; Glute Ham Raise or Back Extension 3 x 15 A simple routine such as the one above could realistically be accomplished through 20-45 minute workouts. The longer workouts for the heavier days such as Bench Presses, Squats, and Deadlifts and the shorter workouts for things like Shoulders, Arms, and Upper back work. To simplify even further, drop the secondary assistance lifts and just perform a series of higher rep back off sets of the main lift. In a format like this, you’d basically perform 3-5 heavy sets in the 3-6 rep range and then follow that up with 2-4 additional sets in the 8-20 rep range for hypertrophy. If you aren’t interested in the higher rep hypertrophy work just do the strength work and go home. That’ll work too. One final variation is for those who want to both Squat and Deadlift with a little more frequency during the week. Since Deadlifts can be adequately trained with just a single heavy set, it doesn’t place that much more of a time demand on your workout to place them directly after squats when not much of a warm up is needed to work your way up to the main set. An easy to follow set up would look like this: Monday: Squat & Deadlift Tuesday: Bench Wednesday: Squat Thursday: Press Friday: Squat & Deadlift Saturday: Accessory Upper body (upper back, biceps, triceps, etc) Any of these routines can work well for clients who want to put an emphasis on cardio work as well. If you can get your strength work done in 20-40 minutes that leaves another 20-40 minutes to hit some cardio work and you are in and out of the gym in an hour having accomplished your strength and conditioning goals for the day. 2 Days a Week Training Template 1 Day 1: Squat - 4-6RM, Back off 1 x10-15 Bench - to 4-6RM, then 2 x 8-12 DB Row/Lat Pulldowns/Chins 3-5 x 8-12 Accessory Upperbody Day 2: Squat - 5 x 5 - light Press - to 4-6RM, then 2 x 8-12 Deadlifts 4-6RM, then back off 1 x 8-12 (could be sldl) Accessory Upperbody Example for Squat - 4-6RM, Back off 1 x10-15: Bar x 20 135 x 5 185 x 3 225 x 1 275 x 1 315 x 6 225 x 12 This is hard but effective. Template 2 I have a 16 year old kid that does this (This Template is obviously also a good choice for older Trainees!): Tues: Squat/Press Thurs: Bench/Deads This kid is the epitome of one and done. He's very neurally efficient and gasses himself rather easily. We do one all out set followed by a single back off set. He Squats and deadlifts in the mid to high 400s, benches 330ish, and pressed 205. We use the following rotation: Week 1: 5s Week 2: 3s Week 3: 2s Week 4: 5s Week 5: 3s Week 6: 1s OR KISS programming for pure strength. Power-building scheme - 1 part strength, 1 part bodybuilding: 4-6 RM with back-off set. Template 3 Jonathan Sullivan: My work (long shifts, life-and-death stuff, stressful), age (50), and other activities (Krav/MMA) limit my lifts to 2x/week. So for my novice progression, I designed a 2-day "staggered" program, which looks like this: WEEK A: Mon: Squat, Bench, Deads, Chins Sat: Squat, Press, Cleans, Pullups WEEK B: Mon: Squat, Press, Deads, Pullups Sat: Squat, Bench, Cleans, Chins This program has me squatting every workout, and doing deads and cleans once a week each. (In truth, I will often do an extra set of cleans right after MMA on Wed, but that's because I'm new to cleans, need the practice, am still at relatively low weights, and just kinda dig doing them.) This program switches out the benches and presses in a way that staggers the recovery times for the two exercises: one week, there's a short recovery for one and a long recovery for the other, and it flips the following week. I realize that this is not The Program, but it seemed the best compromise for a harried Geezer with limited recovery potential. So far, by using this program, going slow (2-5 lb jumps only after the third week), and jacking up my caloric intake by about 20%, I've managed to progress for 12 weeks without getting stuck. YMMV. K.I.S.S. Training Program We all fall victim to it. Over complicating our strength training programs. One expert on the internet says “X” and just a click away, another expert says “Y”. Both sound like great ideas, both guys are respected coaches, and both have plenty of strong athletes under their tutelage. For many of us the result can be the dreaded Paralysis by Analysis. It happens. The best remedy is often just to take a step back, get off all the websites, shut the books, and get back to the basics. Find the simplest program you can find and then EXECUTE IT!!! Turn off your brain and just lift!! I don’t have a lot of time right now so here it is. If you are chronically programming hopping or are just “stuck” not knowing which direction to turn, try this. Its painfully simple, yet very effective. Its about 14 weeks long Monday – Squat Day Wednesday – Bench Day Friday – Deadlift Day Weight Progression (off estimated 1rm) 5 x 5 x 75% 5 x 5 x 77% 5 x 5 x 79% 5 x 5 x 81% 5 x 5 x 83% 5 x 5 x 85% 4 x 4 x 87% 4 x 4 x 89% 4 x 4 x 91% 3 x 3 x 93% 3 x 3 x 95% 2 x 2 x 97% 2 x 2 x 99% 1 x 1 x 101-105% *Add assistance work if you want, but you don’t have to. 2-3 sets of 8-10 for each exercise. No assistance in the 99% week. Deload without Detraining Deloads are something people struggle with. When to take them? How long should they last? Slash intensity, volume, or both? Plan them or take as needed? As with many things, the answer to all these questions is the annoying but true phrase – it depends. Sometimes deloads work like magic, sometimes they don’t. So people come back rested and refreshed, but detrained. Workloads too light, volume too low and unfortunately the result is a fully recovered weaker lifter. That sucks. One of the biggest changes I’ve made in the programming I write for my clients over the last 2 year or so is how I deload them. The long and short of it is – I don’t. At least not in the traditional sense. Meet prep is the exception. What I have been doing a lot of in the last 2 years with a lot of success is FREQUENCY DELOADING. And I don’t change much else. Intensity stays high. Per session / per lift volume is very close, but weekly training volume goes down. The big change is the length of time between workouts. It literally could not be simpler. We’re just taking more time off, and often shortening the workouts. It’s amazing how well it works in most cases. Below are the two primary instances in which I like to use this with my clients. First is the conversion from 3-day per week Full Body to a 3-Day per week Upper / Lower Split. This works really well for guys who HAVE to stay on a 3-day per week plan due to scheduling. Often times life limits us to Mon-Wed-Fri training, and shorter more frequent sessions are not an option, so we keep a 3-day per week plan. We can always drop to 2-days per week for a while, BUT some trainees would prefer just to simply be in the gym more often than 2x/week. And we can accommodate that, but with shorter workouts. So let’s say that a guy is training like this – 3-day per week (sets/reps just for illustration) Monday Heavy Squat 5 x 5 Heavy Bench 5 x 5 Medium Pulls (SLDL) 3-4 x 5 Wednesday Light Squat 3 x 5 Heavy Press 5 x 5 Light Pulls (Chins or BB Rows) 3 x 8-10 Friday Medium Squat or Squat Variant 4 x 5 Medium Bench Press or Bench Variant 4 x 5 Heavy Pulls (Deadlifts 5 x 5) From here, what I might switch him to is something like this: Monday Heavy Squat 5 x 5 Light/Medium Pull (SLDL) 3-4 x 5 Wednesday Heavy Bench 5 x 5 Light/Medium Press 3-4 x 5 Friday Light/Medium Squat 3-4 x 5 Heavy Deadlift 5 x 5 Monday Heavy Press 5 x 5 Light/Medium Bench Press 3-4 x 5 Wednesday Heavy Squat 5 x 5 Light/Medium Deadlift (SLDL) 3-4 x 5 Friday Heavy Bench 5 x 5 Light/Medium Press 3-4 x 5 etc, etc. So you basically have 4 workouts that you roll across a 3-day week that creates a scenario where we have week one as Lower – Upper – Lower and week 2 as Upper – Lower – Upper. Little if anything about the per exercise volume or intensity needs to change. I may keep them on a schedule like this for anywhere from 4-12 weeks and then often times I like to go back to the higher frequency schedule. The second scenario is really even more simple. It basically just takes ANY traditional 4day split (Texas Method, Heavy-Light, Split Routine, etc) and rolls it across a 3-day week. So let’s say our lifter has been having success on the 4-day Texas Method, but is feeling a little sluggish and beat up. I might have him do this for 2-4 weeks: Original Plan Monday – Bench Intensity / Press Volume Tuesday – Squat Intensity / Deadlift Volume Thursday – Press Intensity / Bench Volume Friday – Deadlift Intensity / Squat Volume So now he simply does this: Monday – Bench Intensity / Press Volume Wednesday – Squat Intensity / Deadlift Volume Friday – Press Intensity / Bench Volume Monday – Deadlift Intensity / Squat Volume Wednesday – Start over 4-day rotation As of this writing, my Baker Barbell Club Online crew is starting to hate life just a little bit, as they are in the 11th week of a pretty high volume high frequency Heavy-Light-Medium 12week program. But in a couple of weeks you’ll be hearing the shouts of joy as their programming morphs from a 3-day full body routine, into a 3-day upper/lower split. Not a whole lot will change, but a little more days off between heavy lower body lifting and heavy upper body lifting will be a welcome change and I’m positive the results will manifest in lots and lots of new PRs. Performance Flexibility In the past couple of weeks of doing consultations with some of my clients, there was a reoccurring theme that kept popping up with many of them. The issue was simply having unpredictable performance in the gym. Some days they felt great, other days they felt terrible. Now, these clients are not unique; this phenomenon is pretty much universal. Nobody that trains regularly is “on” 100 percent of the time. We all have bad days in the gym from time to time. Sometimes we can explain it, sometimes we can’t – we are just off. With some trainees, this type of irregularity is chronic. Factors affecting chronic irregularity in the gym might come from the following: 1. Poor Recovery – inconsistent sleep and nutrition. Is sometimes unavoidable (odd work schedule, etc) or is completely avoidable (i.e. you just need to get some discipline and plan better). 2. High Stress – we all get stressed from time to time, but sometimes stress can build up over prolonged periods of time like during a protracted divorce, dealing with a terminally ill family member, managing a struggling business, being out of work, etc. 3. Weight Loss – if you need to lose a bunch of weight, its hard to not lose some strength at the same time. If you are doing a carb cycling approach, then you can be assured that workouts that fall towards the end of a low carb cycle will feel awful, while workouts that fall immediately after a carb load will feel great. 4. Athletics – for those that play a sport that requires lots of conditioning and sport specific practice, gym performance can be negatively impacted. A high volume of wind sprints the day before a squat session is certainly going to have an effect. There are ways to structure practice, conditioning, and strength training for the least amount of impact on performance, but sometimes the ideal training schedule can not be adhered to as a matter of logistics. Whatever the reason for chronic irregular performance in the gym, the trainee needs to find a solution. A training system such as the Texas Method is not only extremely difficult, but it is extremely rigid. If the trainee is consistently up and down in their ability to perform under the bar, it screws up the program. The solution is to find a program that is built around Performance Flexibility. Performance Flexibility is a concept that is nothing more than designing a training program to accommodate fluctuating ability levels from day to day and week to week. In other words, if the trainee is having a horrible day in the gym, there must be some minimums that he must meet before the workout is over, but PRs are not necessarily expected. He doesn’t quit the workout, he doesn’t quit the program. He just meets a few minimum volume/intensity standards and moves on to the next week. Likewise, if the trainee is having a great day in the gym, he should not be restrained in his ability to set a PR – quite possibly a very large PR. After all – the trainee doesn’t know when his ability to set the next PR is going to surface again. So he should take advantage of his increased performance ability NOW. For some reason, I attract a lot of Type A personalities into my ring of consulting clients. Type A’s are good because they generally stick to whatever program I design for them, but they are also a pain in the ass. They tend to want everything to fall neatly into an Excel Spreadsheet. Nothing would thrill them more than to be able to layout 52 weeks of training, set for set, rep for rep, into a nice neat spreadsheet and just go on auto-pilot for the rest of the year. Any time I get into estimations, approximations, or anything uncertain it makes them nuts. If you find yourself amongst those that struggle to maintain consistency in the gym, then you will struggle with the type of long range planning I just mentioned…..UNLESS you build some performance flexibility into the program. Performance flexibility is not a program. It”s a concept that programs can be built around. An excellent example of a program that offers performance flexibility is the Westside Barbell Program. As most of you are familiar with, Westside Barbell uses a Max Effort Day at the beginning of the week for Squats/Deads and for Bench Presses. Each week the lifter selects a variation of the competition lifts and works up to a 1 rep max. That 1 rep max may or may not be an all time PR. Of course the lifter is hoping and trying for a PR, but if its not there, he simply works up to his best single for that day. After the top single, many lifters will do back off sets with a certain percentage of the 1RM they hit on that day. Perhaps 80% for a max set of 5+ reps. At the advanced level of training, performance flexibility becomes increasingly important. As a lifter gets closer and closer to his genetic potential it becomes increasingly difficult to hit PRs with predictable consistency. Using the concept also becomes easier for more advanced lifters because they are a little more in tune with their bodies and their capabilities. They can more readily identify a “good day” versus a “bad day” with objectivity and adjust the training session “on the fly.” If you are struggling with up and down performance in the gym, try and look for ways to build in some performance flexibility into your program. Start by figuring out some minimum’s you must hit at each training session for the workout to qualify as a workout. Then look for a strategy that will allow you to take advantage of a good day. Is it working up to a 1rm in a given lift like Westside? Or perhaps it is simply doing a repetition maximum with whatever load is scheduled to be handled that day. Perhaps a set of 5 is your minimum, but if you feel great, bust out 6 or 7. If all this is very confusing for you and you’d like some help, feel free to hit me up for a virtual coaching session or an all inclusive program design. We can implement some performance flexibility into your current program, or design you something new from scratch. “One All Out Set” vs Multiple Sets So here we are again….. If you’ve been involved in the fitness / bodybuilding / powerlifting world for any time at all then you’ve either had or been witness to this debate multiple times. So if you’re already firmly in the camp of one side or the other and you want to go read something else, I won’t blame you. But as I’ve said before, anytime that I get hit multiple times in the same week with the same question, then it usually gets put in the “potential articles” pile on my desk. I got hit with this one 3 times this week, so I thought I’d share my thoughts on the issue. And the issue at the heart of the debate is this: To get bigger and stronger, is it necessary to use multiple sets (high volume) or can you get the same results (or better result) from training just one all out set to failure?? Like most debates in the fitness/lifting world this debate doesn’t address several key issues. Primarily because most of the people that get embroiled in debates like these don’t know what these key issues are. “Debates” on the internet on this topic usually end with one guy pointing to Dorian Yates and his Mentzer-esque HIT philosophy and the other guy pointing to Arnold and his 30-set Arm Routine as ‘PROOF!” that one side or the other is correct. So what are my thoughts….. I’ll start by pointing out the fact that there is no shortage of successful lifters and bodybuilders that train with approaches at both ends of the spectrum. So for anyone to come out and say that ONLY one way or the other can work hasn’t spent enough time training around really big strong lifters to see multiple approaches work. Either that or he is using “science” to back up a claim for one method over the other. I can tell you right now that there is “science” in abundance to support either side of the argument. So after giving this some thought and reflecting on my own experiences as a lifter, a coach, and an observer I basically think it boils down to a few issues…… Those that have success on the “one set to failure” type of program have basically 2 things in common. 1. First, they tend to be highly neurologically efficient. Highly. Very naturally explosive. The athletes I have trained that have had success on the very low ends of the volume spectrum tend to be competing at a very high level in an explosive sport like track and field. They are capable of imposing a tremendous amount of stress on their bodies with not very much work. So a single set of 5 reps (done all-out) is a different event for a very high level shot-thrower than it is for a more genetically average athlete. I have not had good results with this caliber of athlete on higher volume training programs. But these athletes are the exception and not the rule. And they are exclusively male. 2. They tend to be extremely aggressive trainees who have an iron-will under the bar. They have grit and determination and will push what might be a 5RM for you and me into a 6-7RM. They will not quit on a weight. They have mastered the ability to grind under heavy loads and will do so for more reps than you think they ought to be able to do. (Any chance that there is a link between aggression and explosion??? Maybe starts with a T???) The other issue that I think NEVER gets discussed in the power lifting or body building world is the issue of the TIMING of certain low-volume routines. What do I mean by this? One of the hallmarks of advanced level programming is the concept of accumulation / intensification phases. We wrote about it at length in Practical Programming for Strength Training if you want the details. But basically it boils down to this….peak strength is best achieved by a very high intensity / low volume phase (maybe a few weeks) that immediately follows a phase (or multiple phases) of very high volume / high frequency training. The idea of course being that the lifter approaches the cusp of overtraining by over reaching a bit with volume during the accumulation phases, then drastically peels back volume, and ramps up the intensity for several weeks leading into a meet. It works. It’s one of the easiest and most reliable advanced training programs to set up for a lifter. I’ve done it many times. I also had my own experience with this phenomenon back in college when I was about 20 years old. Interestingly enough, I stumbled onto the discovery by accident and didn’t actually realize I had discovered anything until several years later when I put the pieces together of what actually happened to me. But at the time, I was training with a crew of bodybuilders in College Station TX and everyone in the group was basically following a 3 on 1 off type of bodybuilding split with TONS of volume per body part. Our routines looked something like this: Day 1: Chest, Arms Day 2: Legs Day 3: Shoulders, Back Day 4: Off Repeat. So every muscle group was getting hit 2x/week with probably 10-20 sets at each session. I grew and had a pretty good physique mainly because my nutrition was totally on point and I was 20 years old. After a couple of years of this, I switched gyms and began training with a new training partner. He was older and bigger and so I kinda followed his lead. His philosophy was that each muscle group should only be hit 1x/week for no more than 6-9 sets. So I did what he did. And I went from 180 to 205 in just a few weeks. It was an amazing amount of growth in a short period of time. My other training partners accused me of taking steroids it was so rapid. So what the hell happened? Well, since I didn’t really know anything about programming at the time, I just attributed everything to the new program I was on!!! It was magical!!!! The truth was, of course, is that the new program I was following worked so rapidly mainly because of the TIMING. After 2 years of basically overtraining with too much volume and frequency, my body rebounded like crazy when I drastically dialed back the volume and frequency. I think the same thing happened to the bodybuilders of the Dorian Yates era. For decades many of these guys had been following in the footsteps of Olympians like Arnold and Lee Haney. Very high frequency, very high volume. And these guys set the tone for the elites and average Joes of the gym world. Everyone did what they did. Well then you had the successes of Mike Mentzer and his protégé Dorian Yates who set a new standard for size on the Olympia stage. Leaving the discussion of the advances in chemistry aside for now, Dorian ushered in the HIT era of training where the elites of the bodybuilding world as well as the average Joes at the Y started doing a lot less. And my guess is that many of them had the same experience that I did. They fucking grew. And they got stronger. And like me, they judged the two approaches independently. They failed to appreciate the effects of a very low volume or “one set to failure” approach immediately following years or even decades of over reaching with excessive amounts of volume. So do my ramblings end the debate? Unlikely. But maybe it will give some context. The best way to think about your training may not be to think in terms of High Volume vs Low Volume as an either/or approach. Perhaps the best results come from the intelligent management of periods of higher volume with periods of lower volume/higher intensity. My recommendation is not to spend years on either at the exclusion of the other like the dumb bodybuilders and college kids of the 90s did. Ever Miss Time in the Gym? (How to adjust training when you come back) As a gym owner, strength coach, and personal trainer I simply have to deal with the fact that my clients are going to occasionally miss workouts. Sometimes it’s just a session here or there, but often it may be for several weeks at a time. People travel for business, take vacations, and become ill. And it’s part of my job to figure out how to get them back up to speed as quickly as possible in a responsible manner. My responsibility lies beyond just getting people back to previous PRs, it also means I have to assign them workloads upon their comeback that do not injure them or make them so sore they can’t walk for a week. Over the years I’ve developed a few guidelines that I use to help get people back on track as quickly as possible. Before I go through these guidelines I need to clarify that these recommendations are not absolute nor are they universal. My clients are a diverse group of unique individuals ranging in age from 17 to 88. They are men, women, fit, and fat. Some are experienced lifters and athletes, some are experienced exercisers. This means I have to reign some of them in so they don’t kill themselves and others would be quite content to just restart with the empty barbell. Some clients are strong, some are weak. Some pay attention to recovery, some don’t. Over time, I get intimately familiar with each client and their recovery patterns, and I tweak the following protocols to each and every one of my trainees, but these guidelines are a good place to start if you’ve missed significant time in the gym and don’t know how to re-start training. Rule #1: If you miss a single workout (or even two), don’t worry about it. Very few people are training on such a razors edge of complexity that a single workout missed is going to affect training. If you are that advanced, you probably rarely miss gym time anyways and if you do you already know how to handle it. But for you guys that stress and freak out over the occasional missed workout – stop. You aren’t going to detrain with a couple extra days of rest and if you think you are, it’s likely in your head. The workouts may be harder than they otherwise would have been, but I’d suggest to at least attempt your next scheduled workout and see what happens. If you come up a bit short, don’t worry about it, and adjust your subsequent workouts accordingly. Hell, half the time my clients come back stronger after a few extra days of rest. Now, there is a difference between missing a session because of a work obligation and getting sick. In the case of something like a 24-hour stomach virus or food poisoning, give yourself one light workout back (about 5-10% reduction in loads across the board) and then attempt to get back to your regularly scheduled program. If you are really really sick it might take you 2-3 workouts to get back to regular work set weights, but this is not as common as people missing for less traumatic reasons. If you miss 1-8 weeks of training, adhere to the following guidelines…….. Rule #2: Reduce load on work sets by 5% for every week missed. Pretty self explanatory. For a week out of the gym, reduce loads by 5% across the board. If you miss 4 weeks, reduce loads by 20%. If you miss 8 weeks, reduce loads by 40%. Again, this is not universal, but I have been using this approximation for a number of years at my gym with clients and it’s reasonably accurate. As I stated, individual differences affect this number, as does the reason for the missed time. A prolonged family vacation or business trip is not as traumatic as a major illness. Rule #3: Cut volume by about 25% for every week missed. This applies when a trainee misses 1-3 weeks of training. Beyond 3 weeks, it’s all about the same reduction in volume. So if a trainee misses 1 week of training I’ll usually get him back into the game with about 75% of the volume he had been doing before the break along with the 5% reduction in load. If a trainee misses 2 weeks, I’ll cut his volume in half with a 10% reduction in loads. If a trainee misses 3 weeks or more, he should come back into the gym with about 1/4 to 1/3 of his previous levels of volume. You can cut volume by reducing sets, reducing reps or a combo of both. So a trainee using 3 sets of 5 reps for his work sets might adjust to 2 sets of 5 reps or 3 sets of 3 reps after a week out of the gym. Either is usually fine. The volume reduction simply mitigates some of the potential for severe DOMS after time off. Remember that conditioning fades faster than does absolute strength. Part of our conditioning involves our ability to recover from the stress of training. We lose that pretty fast and volume is the quickest way to severe DOMS. You’ll build your conditioning back rather quickly so don’t stress about cutting a bit of volume after a lay off. Rule #4: Attempt to work back to PR weights at a 1:1 ratio of time missed In other words, if you miss a week, expect 1 week to work back to PR weights. If you miss 2 weeks, expect 2 weeks to work back to PRs, etc. Ideally you’ll want to train as frequently as possible as part of a short term linear progression. But if prior to the hiatus you were squatting heavy 1x/week, don’t expect to come back and immediately be able to squat heavy 3x/week to get back up to speed. I generally base my assumptions and progressions off a 2 day per week frequency for each lift. You have to take into account your soreness and shitty recovery when you first get back under the barbell. Be patient, but don’t stress, it comes back quicker than the first time around……. It may have taken you months to go from 275 to 315 the first time you achieved this goal. You had to build new tissues and lay down the neurological hard-wiring to put 40 lbs on your squat. However, getting back up to previous PR weights, doesn’t take nearly as long. Keep in mind that conditioning dissipates fast, but it comes back fast too. Most times, your ability to get back into the volume (which is partly a conditioning adaptation) will come back faster than the loads on the bar. Putting it into practice……. Let’s say you squatted 275 x 5 x 5 (5 sets of 5 reps) before you had a business trip that didn’t allow you to train with barbells during that time. Here are a few examples of how to handle your re-entry back into the gym: One Week of Missed Training: 95% of 275 is 260. We’ll call it 255 to hedge a bit and give us more even numbers to work with. 75% of the total volume is 18 reps. We’ll call it 15 reps. Workout 1 (Monday) would be 255 for 3 sets of 5 reps or 5 sets of 3 reps. Workout 2 (perhaps done on Thursday) would be 265 for 4 sets of 5 or 5 sets of 4 (20 reps). The following week, you should be good to go for 275 x 5 x 5. This gets you two lighter lower volume sessions under your belt and gets you back into PR territory within 1 week. Two Weeks of Missed Training: 90% of 275 we’ll call 245. 50% of the volume is about 12 reps. Workout 1 (Monday) would be 245 for perhaps 4 sets of 3 reps. This would be very manageable. Workout 2 (Thursday) would be 255 for 4 sets of 4 reps. Workout 3 (Monday) might be 265 for 5 sets of 4 reps Workout 4 (Thursday) might be 275 for 5 sets of 5 reps. This gets you back into PR weights at the end of the second week back into the gym after a 2-week hiatus. Four Weeks of Missed Training: 80% of 275 is 220. We’ll call it 225 for ease of plate loading. 25% of the volume is 6 reps. We’ll call it 10. Workout 1 (Monday) would be 225 for 2 sets of 5 reps. Workout 2 (Thursday) would be 235 for 3 sets of 5 reps Workout 3 (Monday) would be 245 for 4 sets of 5 reps Workout 4 (Thursday) would be 255 for 4 sets of 5 reps Workout 5 (Monday) would be 255 for 5 sets of 5 reps Workout 6 (Thursday) would be 260 for 5 sets of 5 reps Workout 7 (Monday) would be 265 for 5 sets of 5 Workout 8 (Thursday) would be 270 for 5 sets of 5 Workout 9 (Monday) would be 275 for 5 sets of 5 Let me simplify and summarize for you how to work this process, as the examples above are just that. Examples. Each trainee might add load and volume back at a slightly different pace. 1. Use the 5% and 25% rules for establishing the first workout back into the gym. Get this one right. 2. Use the 1:1 ratio rule to set your old PR workout up on a day in the near future that is approximately equal to the number of weeks missed (i.e. plan your old PRs 2 weeks from the date of your first workout back if you missed 2 weeks of gym time). 3. Between the re-introduction workout and the PR workout, increase both volume and intensity in manageable and even increments until you hit your old numbers. I suggest you pre-plan all this out, but also be flexible and adaptable if things start to come back quicker than expected or progress slower than expected. If it takes 1-2 workouts longer than expected to get back to your old numbers, so be it. 4. Train each lift 2x/week increasing volume and/or intensity a little bit each session. If you miss really long stretches of time (more than 8 weeks) then these formulas become less reliable. In those instances, I suggest you simply “start where you are at” and work off of a top single your first time back in the gym. You don’t have to perform a 1-rep max, but working up to a quick single can give you an idea of where you are at, and starting back at say 70% for 3 sets of 5 reps might be a good place to restart a short 2-3x/week linear progression to get yourself back in spitting distance of your old PRs. 2 Random Pieces of Training Wisdom As I sat down at the computer this morning to knock out an article, it was just one of those days where I sat staring at the blinking cursor and not much was going on upstairs. I’ve written enough material over the last several years to realize that sometimes you have it, sometimes you don’t. It’s very difficult to generate anything useful into text when it’s just not there. So instead of trying to put together some well thought out, long drawn out article, I started scribbling down random pieces of advice I’ve been given over the years from some of my coaches, training partners, meet competitors, or even some of my clients. I thought I’d share them with you today. Maybe they’ll help. #1: 80% of the Time, Train at 80% This is a good little rule of thumb for program design. This essentially refers to something that we already know which is that the best “strength building” range is between 75-85% of 1RM. And the vast majority of our barbell work should come in this range. Practically speaking this is basically the 4-6 rep range for most of us. I remember giving this piece of advice at a Starting Strength seminar a few years ago to one of the attendees, and I was oh so gracefully corrected by Rip. “What Baker means by 4-6 reps is FIVES!” So yeah, basically sets of 5 reps make a good base of any program, whether its novice, intermediate, or advanced. So what do we do with the other 20% of the time? Well, very loosely speaking we’d be doing maybe 10% of our work over 90% (sets of 1-3 reps) and another 10% of our work in the 8-10 range for muscle building and work capacity, mostly on the non-barbell work (machines, dumbbells, etc), although it’s not a bad idea to occasionally knock out some higher rep barbell work as well. Before you get out your calculators and start trying to figure out if you are doing exactly 80% of your work at 80%, STOP! Just keep the spirit of the cute little saying in mind. In reality, for an intermediate or advanced trainee I’d probably have them doing more than 10% of their work in the 90%+ range. But you get the point….don’t stray too far away from your mid-range work of 4-6 reps in the 75-85% range, for most of your barbell work. But don’t forget that we need a neurological stimulus with sets in the 1-3 range and a little bit of higher rep work in the 8-10 range as well. #2: Focus on Throwing Touchdowns, Not Interceptions I love to use analogies when I’m coaching clients. This is one of my favorites and I use it all the time here at the gym and with my online coaching clients. Basically this one has to do with failed reps and injury. I believe this to be 100% true….those trainees who approach a heavy lift thinking about failed reps and injury tend to fail their reps or get injured. It becomes a self fulfilling prophecy for them. It’s a mindset issue. Some clients are very aggressive under the bar, some are very timid. Over time the timid can learn aggression, but it takes some mental/emotional work on their part. In other words….if you are approaching your first 315 Squat thinking to yourself “Please don’t fail! Please don’t fail!” Well, you’re probably going to fail. And I guarantee there are A LOT of you guys reading this post right now that have the “failure” mindset in the gym. This causes you to do two things, neither of which are productive. First, you’ll have a lot of missed and failed reps in the gym. You’ll quit on a set at rep #4, when you could have gotten 5. You were just too scared to grind it out. So you never learn how to grind and you never get the psychological or physiological benefits of completing a completely limit set. The second thing you’ll do is frequently rationalize the need to “reset.” I’m actually really starting to hate this term and this tactic because people are doing it way too often. The “reset” is being used when things get heavy. But when things get heavy is when you get strong. You’ve got to learn to push through those really really heavy sets, then rest 5-8 minutes and push through it again. But if you “reset” every time the weight becomes a challenge you’ll never going to get strong. So you need to get really honest with yourself. Do you really need a reset? Or do you really just want a reset? I think in a whole lot of cases, lifters don’t actually need a reset. But they justify one by convincing themselves their “form was off.” That’s a very common excuse. Don’t get me wrong…if your form is totally fucked and you’re training too heavy with bad form, then you might need to reset to clean things up. But sometimes I’ll have lifters send me video where literally ONE REP out of their entire 3×5 workout was high, or their knees caved in, or some other minor error was committed, and they are asking me about a reset. NO!!! Just clean it up next workout and carry on! So this goes back to the Quarterback analogy. When Tom Brady drops back in the pocket I guarantee you he is thinking “TOUCHDOWN!” Or at the very least – completion! And guess what, he throws a lot of touchdowns and very few interceptions. Natural ability, coaching, and work ethic aside – a lot of his success comes from an extremely aggressive mindset. He’s out to fucking WIN on every pass he throws. Now, if you are a Houston Texans fan like me you had the unfortunate experience a few years ago to watch Matt Schaub completely implode. A formerly pretty damn good quarterback completely lost his confidence and inside of just a few games his career was ruined because he lost his mojo. He didn’t get old or injured – he just lost confidence. You could almost see the thought bubble over his head when he dropped back to throw a pass “Don’t throw an interception! Don’t throw an interception!” And guess what….for a time, all he did was throw interceptions. It became a self fulfilling prophecy. Many of you have that same approach under the bar. When you approach a heavy squat or deadlift, you are thinking about throwing an interception instead of throwing a touchdown. Trust in your mechanics and give it 100% and don’t quit until you meet your goals. Success is the biggest driver of confidence. All you need is a few workouts of completing sets you didn’t think you could complete and your confidence will grow, as will your approach under the bar. 6 Reasons Why Your Training is STUCK (Part 1 of 2) Ever been STUCK in your training program? Ever review your training log and realize that despite your best efforts, the last several months really hasn’t generated any substantial progress? Of course you have. We all have. Sometimes these things happen that are beyond our control. Most of us have had some kind of injury that has set us back. We’ve all had the flu or a stomach virus. Sometimes family vacations or business travel put is in locations without access to adequate equipment. These things are going to happen and in my last article we looked at a few ways to navigate a comeback after a longer than expected lay off from the gym. However, the purpose of this article is to examine some behavior patterns that are SELF INFLICTED. In other words, these are behaviors or habits that “stick” our progress when we are trying like hell to make progress. That’s the most frustrating aspect of training. When you feel like you are putting out your best effort and just not getting a return on your investment of time in the gym. I do a lot of distance coaching with clients not training in my gym via phone and email. I’ve done it for years and so I’ve seen a lot of the same patterns repeated over and over again. And over again some more. 9 times out of 10 the person who contacts me for consultation is someone who fits the description from above – training and trying hard, but just seems to be STUCK. They are frustrated beyond belief. They keep coming up to the same numbers and stalling out in the same old places on all their lifts. Over the years I’ve identified 6 primary categories where people keep sticking themselves. For some people, it’s just one category, most people fall into multiple categories. Some are victims in all 6 areas. Each category is it’s own coin with two opposing sides to it, so I guess technically there are more like 12 potential pitfalls we’re trying to avoid. Let’s take a look today at the first THREE major categories that hang people up: 1. Form & Technique In scenario 1 our trainee hasn’t mastered the basic mechanics of the major lifts. Most people know when this is an issue, but some people don’t treat it seriously enough, and many aren’t willing to invest the time and potentially the money to get their form fixed. Look, some people need coaching. Some need it more often than others. But certain technique flaws in a squat, deadlift, press, or bench press must be corrected or you’ll never progress or you’ll keep getting injured. If you keep shooting your ass up in the air on a deadlift you’re going to get stuck coming off the floor. There is only so much weight you can pull off the floor with straight knees and a rounded back. And if you keep trying you’re gonna hurt your back. If you keep trying to lift your chest instead of drive your hips on the squat, you are going to keep missing reps halfway up on hard reps. If you keep letting the barbell track forward of the midfoot on a press, you are going to keep missing at nose level. All the programming tweaks in the world aren’t going to fix bad mechanics. Read and reread Starting Strength. Post videos to Starting Strength Coaches (this is free by the way). If you keep fucking up, hire a Starting Strength Coach for a few hours. Or a few weeks. Even if you have to travel a bit. Again – some people need in person coaching. We’re not all good athletes. Some of you are motor morons (I say this with all due respect!). But if you can’t hold your form together, you need a hands-on coach. YouTube video demonstrations help, but it may not be enough. You need someone to yell at you or even physically adjust you….in real time. True coaching is done in real time, on the platform. Get yourself fixed. In scenario 2 we have the other end of the spectrum. We have the guy who has basically mastered the form on all the major lifts, but is too timid to take this ability and run with it. The fitness world is wrought with Obsessive Compulsive tendencies. Your form needs to be good, but it doesn’t need to be 100% perfect on every rep of every set in order for you to keep progressing. If 90% of your reps are clean – good! Keep going! As long as you can identify your form errors when they occur and work to correct them as you go, you’ll be fine. Don’t ignore flaws and don’t let them get worse, but don’t let them hold you back either. I’m not kidding when I say that I’ve had people tell me that they reset all their Volume Day weights because 1 or 2 reps were “just a little bit high.” In other words in a 5×5 squat workout, 23 of the 25 total reps were clean. But 1 or 2 of them were a little high, so they reset everything by 10%. NO, NO, NO!!!!! Cases like these are an example where Perfectionism is Killing Progress. Keep working to clean up form flaws, get coaching if you think you need it, but don’t use an error here and there to justify being a pussy. Put weight on the bar forge ahead. If I reset my clients every time they made a mistake on a lift, no one in my gym would be squatting past 135. We’d spend all day drilling technique and never getting strong. Training is a constant refinement of technique. Always pursue better technique, but don’t forget we’re training for strength, not technical perfection. 2. Programming Again we have two types of people here. Trainee #1 is suffering from the deadly disease of CHP – or Chronic Program Hopping. You know who you are. Every week it’s something new, hoping you’ve found the magic bullet. A trainee has a bad workout on his Texas Method Intensity Day on Friday…so Monday begins Wendler’s 531. Well, that didn’t feel like enough volume so let’s try the Smolov Squat Program the next week. Wow, overtrained after a week, so let’s dial back on the volume and do a 2 day per week maintenance routine. Well that was boring, Westside looks fun, let’s try that this week. I’m serious. Sometimes it’s that bad. Listen, there is no perfect program. Jumping around from one thing to the next every week is a surefire way to stifle progress. In the military we used to say that one bad plan is better than 10 good plans. It’s true. Find something that makes sense for you and stick with it for 12 weeks. Try not to adjust every major variable every week. Just right down your plan and stick with it. Re-evaluate at the conclusion, make some adjustments and keep going. If things don’t work, well at least you have learned what doesn’t work for you. Over time, you’ll start to get a feel for what works and what doesn’t for you and you can start writing your own programs that fit your needs better than anything you can find in a book or online. But you have to see things through long enough to determine whether it works or it doesn’t. Trainee #2 is what I call the Stubborn Spreadsheet Warrior. This is the guy that has been doing the Starting Strength Novice LP for 2 years. He stubbornly refuses to admit that he has exhausted all the potential for his current programming and wants to squeeze out every last bit of progress before moving onto the next thing. Even if he’s not making progress. Look, I don’t want you hopping from one thing to the next every week or every month. Consistency is a virtue in training. But there is such a thing as “going stale.” You can’t do the same routine year in and year out and get progress without some sort of build in fluctuation in the degree and type of stress you apply to yourself. I’ve looked at training logs from clients who haven’t trained in a single rep range except for FIVE in 2 years. That will never work. You go stale, mentally and physically. Remember what I said about OCD tendencies? You need adjustments in volume, intensity, sets, reps, frequency, exercise selection etc from time to time. Fives will always be a staple, but you can’t get strong without occasionally challenging some heavy singles. You won’t grow as much without some work in the 8-12 range. You need it all once you are out of the novice stage. There are times for hitting it hard 5 days per week and there are times to throttle back to twice per week. Don’t be a slave to any one program if you haven’t gotten any stronger in weeks or months. I’m not sure why, but these types of clients just love spreadsheets. Show me a client with 2 years of no progress on the same program and I’ll show you a spreadsheet that has documented the whole journey. 3. Conditioning / Cardio Most of you reading this article are interested primarily in one thing – STRENGTH. Cool. Me too – primarily. So most of us want to be strong first, but we’d also like to “look like we lift” and we’d like to have enough cardio to go for a hike in the mountains without an oxygen tank. Most of us recognize the need for some conditioning work in our training program, but many of us will overdo it and kill our strength gains. I get it. Many of you like to run. But you have to come to grips with the fact that long distance running and heavy duty strength training are not all that compatible. I have clients that are not going to give up their daily 3 mile jog. It’s a mental and physical release for them. It clears their heads and gives them a physical high. Fine, but for 90% of you, don’t expect to squat 500 and still keep up your daily jog. If you are long distance running to try and get rid of your beer gut, stop. Fix your diet first. The beer gut is from the beer, not because you don’t run. Body composition is primarily diet + strength training. A little cardio here and there can help “smooth out the wrinkles” from a diet that isn’t 100% perfect all the time, but don’t try to use cardio to counteract the effects of a shitty diet. On the other end of the spectrum, we have the guys that are purely anti-cardio. They believe that even walking through the cardio section of their gym on the way to the bathroom might put them into a catabolic state. This is purely bullshit. Some cardio is good for us. As I mentioned above, if you are a natural fatty like me, then a little cardio in the mix will help smooth out the wrinkles in your diet and keep your metabolism elevated so you can process a high calorie diet for more productive purposes and keep body fat at bay. But body composition aside, good cardio fitness can actually help your strength gains in my opinion. Louie Simmons talks at length in many of his articles as to why he has all of his lifter drag a sled on a fairly regular basis….you have to be in shape to train. Many of you only think about this in reverse – I have to train to get in shape. Both are true. We talk about Work Capacity and GPP (general physical preparedness) all the time. That basically refers to the fact that a certain amount of aerobic and anaerobic fitness will help you train harder and longer in the gym. You can fit in more exercises and take less rest time between sets. You won’t gas out as easily on that 5th set on a heavy 5×5 workout. You’ll have the energy to perform a few assistance exercises on the tail end of a draining barbell based training session. Some degree of volume is a necessary component of continual strength gains and muscle growth. But to perform multiple high volume workouts in a week, you need to have good general fitness. A little bit of the right type of cardio can help with that. I also feel that a little cardio during the week helps with between workout recovery. Moving blood around the whole body helps with recovery so we aren’t chronically sore, stiff, and beat up. My faves are sled dragging, incline treadmill walking, airdyne type bikes, and elliptical trainers. None of these make you sore or add too much to general fatigue that competes with recovery from heavy training. 20-40 minutes at a time 2-4 times per week is enough for most. Remember, we’re not trying to prep for the Crossfit games. We’re just doing enough to slightly improve our cardio base for weight training. I also like circuit training with non-essential assistance exercises for conditioning. We don’t do this with major barbell exercises, but after you squat and pull heavy, you can set up a lower body based circuit that include 2-4 exercises such as Weighted Step Ups, 45* Back Extensions, Sit Ups, and maybe even calf raises for 10-20 reps each repeated for 2-4 rounds at a quick clip. This won’t take long and will help with conditioning. In part 2 of this series, we’ll look at 3 more areas that contribute to trainees getting STUCK in their training including assistance exercises, training intensity, and “expert” advice. 6 Reasons Why Your Training is Stuck (Part 2 of 2) In part 2 of this series we’ll take a look at 3 more reasons why people stagnate and regress in their training plans. Once again, in all 3 of these areas, we’ll see a spectrum, and those that exist too far on either end of the spectrum seldom make much progress. 4. Assistance Exercises Assistance exercises are a hot topic in strength & conditioning. Whether training for just pure strength, mass & physique, or sport the role of assistance exercise is confusing to many. First let’s define what an assistance exercise actually is and how it relates to your training. Whether you are training for pure strength, sport, or physique, the primary basic barbell movements are generally always fairly constant – Squats, Deadlifts, and Presses (standing press and bench press). In addition, I’d probably throw in Chin ups / Pull ups as a “semi-core” exercise, and for various types of sports I’d also include the Olympic lifts. These are considered the primary lifts mainly because they satisfy 3 major criteria – lots of muscle mass trained, complete range of motion around multiple joints, and they allow for significant poundages to be lifted. For a novice trainee, not much else needs to be done other than these 3-6 major exercises. And even for advanced and intermediate trainees, these lifts should always form the core of the training program. Getting stronger in these 3-6 basic movements will have DIRECT carryover to whatever the trainees goal – strength, mass, or sport. Without them in the program – results will be less than optimal. However, very few trainees can make a complete career out of training JUST these basic exercises. Despite the nearly infinite permutations and manipulations of volume, intensity, and frequency, at some point most lifters will need some exposure to other movements for optimal results. For a strength trainee, weak points / sticking points will often keep a lift from progressing. Often times this is the inability to finish or lockout a lift, such as in a Deadlift or Press. There are assistance exercises to help with this or “overload” a sticking point. For a physique oriented lifter, complete development of all the major muscle groups cannot be achieved without a pool of assistance movements to rotate through. In addition, any lifter (strength, physique, or sport) can fall into physical and mental ruts if nothing but the basics are used. I see this quite often with Deadlifts. No matter what we do with a trainees set/rep scheme, the Deadlift just doesn’t want to budge off a certain number. Sometimes the best advice I can give someone is “don’t deadlift” for about 6-12 weeks. Instead, pick a couple of variations (ex: Rack Pulls and Stiff Leg Deads) and alternate them every other week for 6-12 weeks and then resume deadlifting. Usually a small PR is the result of such a change. Bill Starr was doing this with his athletes back in the 70s. My friend and mentor Mark Rippetoe uses Rack Pulls and Halting Deadlifts for intermediate trainees “stuck” on the Deadlift. Often times, however, we see lifters stray too far away from the basics with too many variations of the primary lifts or variations that simply have no carryover to the primary exercise. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. At a certain point in your lifting career there is a need for experimentation. You need to try new programs, new set and rep schemes, new training splits, and yes, new exercises in order to find what works for you. During this process you may indeed spend some time doing things that don’t work. But that’s why we call it experimentation. There isn’t always a guaranteed result. As long as you learn from your failures, then I don’t consider it a mistake. If you want to get to a point in your career where you can design your own programs for yourself (and certainly if you want to coach others) you will inevitably try some things that don’t pay off. So some experimentation with new protocols is acceptable, encouraged, and even necessary for long term success. However, perhaps I can save you some time by warning you that very rarely do programs work include little to no focused effort on the basics. The Westside Barbell method of training is a popular training style for many competitive lifters. I’m a fan of “the conjugate method” (i.e. a frequent rotation of exercise variations), Louie Simmons, and all things Westside…..for the most part. However, I think that many lifters have ventured into Westside styled programming and gotten lost in the weeds. The main mistake lifters make is too many exercise variations without enough frequency on the tried and true basics. Box Squats, Pin Squats, Safety Bar Squats, Cambered Bar Squats, Front Squats, Banded Squats, etc are all fine by me…..but NOT at the exclusion of an old fashioned back squat. If you want to be a good squatter, you have to squat. If you are an experienced lifter, do you have to Back Squat at every lower body session…..no. There is enough evidence to support that a small pool of squat variations, mixed with the basic lift, can yield steady progress. The same goes for Benching, Pressing, and Deadlifting. Performing partial variations of the lifts, adding bands or chains, or using specialty bars are all fine….as long as the core of your programming still includes the tried and true basic lifts. So on one end of the spectrum, we have the trainee who gets carried away with assistance work and variations of the basic lifts and doesn’t make progress. On the other end of the spectrum is the Mike Bridges inspired lifter. For those of you who don’t know, Mike Bridges was an elite powerlifter who made a name for himself with the most barebones style of programming imaginable – Squat, Bench, Deadlift 3 days per week with only the volume and intensity manipulated. Did this work for Mike Bridges – yes. Has it worked for other lifters – yes. Will it work for the vast majority of trainees training for strength, physique, or sport – no. Not in my experience anyways. So the optimal results are, once again, found somewhere in the middle of the spectrum. As a general rule of thumb I’d say that 60-80% of your training sessions should BEGIN with one of the basic primary lifts – Squats, Deadlifts, Presses, or Bench Presses. Following those lifts there is room for a small assortment of assistance exercises that will build up the constituent muscle groups used in each lift. For example, after we Bench and Press there is room for things like Dips, DB Press variations, and isolation tricep exercises. This will eliminate weak points as well as build a better physique. And if you begin 60-80% of your sessions with the basics, that means 20-40% of the time it’s acceptable to begin a workout with a close variation to the parent lift – incline presses, rack pulls, or front squats for example. This will keep your mentally and physically fresh, sure up weak points, and keep your training fun and interesting. 5. Intensity Anyone reading this probably has a primary interest in getting strong. And we all pretty much know that the most direct means of getting strong is to train with heavy weights. However, many lifters overdo it when it comes to loading. In other words, they spend too much time and energy “testing” strength instead of building strength. Training at or above 90% of 1RM strength is the most direct means of training force production. This intensity range will generally yield sets in the 1-3 rep range. This is a very powerful tool, but it must be used somewhat sparingly. Week in and week out of training at or above 90% will result in some rather extreme fatigue of the central nervous system. We often refer to this as “frying your CNS.” Some training styles (think the ever popular Bulgarian method) rely on near daily “maxing out” of lifts like the squat, front squat, clean, and snatch. This has worked for a few genetically elite and often chemically enhanced lifters. What you don’t hear about are the scores of lifters who completely crash and burn using this style of training in just a few weeks. For many the ability to “adapt” to this style of training is non-existent. Some schools of training (think Westside) also “max out” on a very frequent basis, but rarely with the same lifts week to week. So each week the lifter is working up to a 1RM, but on different exercises. This changes the loading week to week and often circumvents potential CNS fatigue. However the better way to go about this is to spend more time building strength, mainly with reps in the 4-8 range, with the occasional venture into higher intensity zones. Most of the programs I use for intermediate and advanced clients have trainees using loads at or above 90% once every 3 weeks. The other weeks of the program are spent in the midrange of 75-85% of 1RM. So on one end of the spectrum we have trainees that get impatient with the “building phase” and want to “test” their strength too frequently, resulting in chronic fatigue and frequent brushes with overtraining. On the other end of the spectrum we have those who never get comfortable handling heavier loads – either out of fear or an illogical addiction to the 5 rep set. Don’t get me wrong, sets of 5 are a staple of every training program I write. However, if you want to get good at straining against really heavy weights…..you have to strain against really heavy weights. At least every 3-4 weeks, most every intermediate or advanced athlete should be venturing into the 1-3 rep range with loads at or above 90%. Some may benefit from going heavier more often (every other week) or even once per week, although this approach will need to be offset with some planned deload weeks or at least the occasional week off from heavy neural work. Although we don’t want to “fry” our CNS, we do need to train our CNS…and that means heavy singles, doubles, and triples as a regular part of the training plan. 6. Expert Advice I’ll make this last part short and sweet since it’s rather self explanatory. In the Age of the Internet, “expert” advice is everywhere. As a strength coach with an online business I know first hand that I’m in competition with literally thousands and thousands of “online strength coaches” vying for your business. Trainees are getting hundreds of mixed messages everywhere you go. The deadly disease of CHP (chronic program hopping) was not as pervasive in 1995 as it is in 2016. Information is everywhere….much of it is conflicting, much of it is just plain wrong. As I mentioned in the previous article – one less than perfect plan (I won’t say bad plan) is better than 10 good plans. Too many guys are trying to follow the WestsideWender531StartingStrengthCrossfitPhilHeathMassAttackEdCoanPowerlifting plan and getting nowhere. Your best defense against silly bullshit online is experience – your own experience. Don’t be afraid to experiment for yourself and see what works for you. And if something is working, no matter what any “expert” says about your plan, keep following it. Find someone, or a handful of someones, that you trust and listen to them, but weigh it against your own experience. I encourage you to read everything you can, but do so through a very discriminating filter. If it sounds like bullshit, it probably is. There main criteria I’d look for in a trusted resource in an online coach or mentor is – Does this person actually coach real people??? Does he or she run a 100% online coaching practice or do they actually get out on the platform or gym floor with regular every day folks and make it happen. In other words – does their mortgage payment depend on this person getting real results with real people? People like Mark Rippetoe no longer coach personal training clients…..but he did so for 30 YEARS before he launched his first book! Do I sell and promote online programs and products – you bet, but I also coach clients for 8-10 hours per day and I’ve owned my gym for nearly a decade! It’s easy to throw up a website or blog…not so easy to run a profitable gym for 10 years. If your methods are bullshit, you won’t last. So the moral of the story is this – expert advice is how we learn and grow as lifters and coaches, but nothing is as powerful as your own experience under the bar. Don’t rely 100% on one or the other. Monthly Programming – Two Steps Forward, One Step Back One of the simplest ways to introduce a trainee to the concept of “advanced” programming is through the Two Steps Forward, One Step Back model. Before we get into the nuts and bolts of the model, it’s first useful to discuss a few points about terminology. First, and most problematic is the term “advanced.” When we talk about “advanced” lifters, it doesn’t necessarily mean that this person is highly competitive at the elite level of power lifting, it doesn’t mean they have been training for 10+ years, and in some cases it doesn’t even mean they are all that strong (depending on how you define strong). In this instance, “advanced” simply means that our trainee has reached a point in their training career where attempting to set PRs on a daily basis (novice) or weekly basis (intermediate) is no longer possible. Instead the trainee should be programming with the longer game in mind, and PR attempts on the major lifts should be attempted with less regularity. How much less? Every 2 weeks? Every month? Every 6-8 weeks? Quarterly? Twice per year? Well it varies, and this is why there is no clear dividing line between intermediate and advanced lifters, and you don’t necessarily go from weekly to monthly progression overnight on all your major lifts. It’s a slower and more gradual process, and experience has shown that the lines between intermediate and advanced programming can be blurry enough to make the strong case that there isn’t much of a line at all. There is a time in the immediate post novice window (several weeks to several months usually) where trainees are indeed capable of weekly progression on the major lifts, where as a novice, we were setting PRs 2-3 times per week. We tend to call this stage early intermediate training where PRs are occurring on the major lifts at approximately weekly intervals. However, once this runs it’s course, we have to start planning our heaviest and hardest sessions less frequently. We simply cannot create enough stimulus across the span of 1 or 2 days or even 1 week that is sufficient enough to drive new adaptations that can be displayed every single week. The build up process takes longer now. We need to accumulate stress over the course of many days or even several weeks in order to force the adaptations we are looking for, and we have to have a window of time prior to our “performance” days that allow some built up fatigue to dissipate enough to be able to actually set new PRs. Just because you are capable of that 500 lb squat, doesn’t mean you are capable of that 500 lb squat today. So the Two Steps Forward, One Step Back model is a means of addressing these programming issues. The “Two Steps” represents a period of “build up” or volume accumulation. This is the real work the trainee is doing in order to build the muscle and strength necessary to display a new PR later in the month. The “one step back” part of the nickname represents a week of lower volume and sometimes a bit lighter training that allows for fatigue to dissipate in preparation for the PR week. Now, one of the problems with the program’s nickname is that the trainees or coaches might box themselves in with the “Two Steps” part of the month and think that all the volume accumulation work must be done in two weeks. I’ve found my best results with Three weeks – so Three Steps Forward, One Step Back is just as viable. Trial and error is your friend here. Start with a two week build up and then if you aren’t happy with your end of cycle performances, add a third week to the build up phase. My rule of thumb in most programming troubleshooting is that stagnation requires more work and regression requires less work. Strength tends to be easier to maintain than build. And this programming approach isn’t pushing the boundaries of volume or intensity so hard that large scale regression is likely to occur. So if you aren’t making much progress – add a little more work. Two Steps Forward, One Step Back Week One: Moderate to High Volume, Moderate Intensity Week Two: High Volume, Moderate to High Intensity (i.e. pushing volume PRs) Week Three: Lower Volume, Maintain or slightly reduced intensity Week Four: Moderate Volume, High Intensity Three Steps Forward, One Step Back Week One: Moderate to High Volume, Moderate Intensity Week Two: Moderate to High Volume, Moderate Intensity Week Three: High Volume, Moderate to High Intensity (i.e. pushing volume PRs) Week Four: Lower Volume, Maintain or slightly reduced intensity Week Five: Moderate Volume, High Intensity Volume & Intensity for each week……. Here is where the rubber meets the road and where the details matter. It’s difficult to give out a blanket prescription that will suit all trainees, mainly because it doesn’t exist. You have to base these numbers off of past training history to figure out exactly how to dose all these variables for each individual lifter. I usually start with the “performance week” and try to figure out exactly what we’re going to use as our measuring stick to see whether our programming is optimal. “Performance” week does not mean a 1-rep max test or mock meet every 4 weeks. This is unnecessary and counterproductive. I prefer to be more in the range of about 90% of 1RM with a low to moderate volume of work. It’s a “test” yes, but we also want to do enough work to simultaneously serve as a stimulus. I think a real sweet spot for this type of work is in doubles and triples across. Usually like 3 sets of 3 reps or 4-5 sets of 2 reps with a weight that is approx 90% of a 1RM. This means that the work in the build up weeks would range from 70-85%, with most of the working coming in at the 75-80% range. So if we have a lifter who prefers to Squat 2x/week, we might have one heavy day of squatting per week paired with lighter deadlift variants and one lighter day later in the week where the lifter squats at a low intensity for speed paired with heavy deadlifts His very simple 5 week Squatting cycle might look like this: Week 1: Monday 5 x 5 x 70% Thursday 10 x 2 x 60% Week 2: Monday 5 x 5 x 75% Thursday 10 x 2 x 65% Week 3: Monday 1 x 3 x 85% / 5 x 5 x 80% Thursday 10 x 2 x 70% Week 4: Monday 3 x 3 x 80% Thursday 5 x 2 x 70% Week 5: Monday 3 x 3 or 4-5 x 2 x 90% Thursday 3 x 5 x 70% Sets and reps and exact % may vary of course. And some lifters like the speed work, some don’t. Plain old light squats or a squat variant is also fine on this second day of the week. So this is all very malleable to an extent. But the gist of the program is that you should try and spend 2-3 weeks building up some volume. Start the first week fairly light to recover from the 90% work from the previous week and build up the intensity over a 2-3 week period. In the final week of the volume loading, really push yourself during those volume workouts with some hard and heavy 5×5 work and aim for new PRs here if possible. Then take the deload for a week which should maintain your intensity (for the most part) but drop volume. And then aim for some heavy PR sets in the 90%ish range in the 4th or 5th week of each cycle. Follow this with multiple 4-5 week cycles arranged in roughly the same fashion and you can train for many months and make progress. Programming Assistance Work We know there are 101 ways to effectively program our main lifts – the Squat, Bench, Deadlift, and Overhead Press. There is much confusion and much debate as to what works best, why, and how, and I believe much of the confusion exists precisely because so many different things actually do work in practice. The same is true with assistance work. People go about things differently and yet many different approaches work. Some guys rigidly try to plot our every rep and every set for the next 6 months on an Excel spreadsheet that’s more complex than mapping the human genome. Some guys completely wing it. They go to the gym with very little plan for their assistance work and go completely by feel. Exercise selection, sets, reps, weight, tempo, rest periods, etc are all done by feel. Nothing is recorded or tracked. Really neither end of the spectrum is ideal. I believe at least a loose plan for your assistance exercises is best. And this may actually mean planning to be random. But either way, you need to be tracking your exercise selection and recording weights, sets, reps, etc so that progress can be measured over time, and as importantly, we want to be able to track how our main competition lifts respond to increases in strength in our assistance work. Over time you are going to want to identify those assistance lifts that have carryover to your main lifts and those that don’t. For instance if you go from a 315×5 Stiff Leg Deadlift to a 365×5 Stiff Leg Deadlift, you need to pay attention to how this affects your Deadlift performance. Are your reps getting easier/faster at heavier loads? Are you able to train heavier? Do more reps? Whatever, but if you are making 10-20% increases on a supplemental barbell exercise there should be some positive transference to the main exercise. If you’ve spent a substantial amount of time on an exercise, gotten a lot stronger on that exercise, continued to train your main lifts, and notice zero carryover – then maybe that exercise doesn’t need to be in your tool kit. Below are a few ideas to help you better program and progress your assistance work. #1 Keep Main Lifts Fairly Constant, Alter Sets / Reps / Load I like variety in programming, however, this is one of those factors that varies quite a bit on an individual level. Some guys need a lot of frequency on a given lift in order to maintain their technique and confidence. Some don’t. But I think for most trainees you need to be doing your main competition lifts (Squat, Bench/Press, Dead) at least once per week, along with some very close variations of those lifts another 1-2 days per week. Some may do better to ditch the variations and do light / medium days of the competitive movements. The reason we need to keep the main lifts in the program is (1) to maintain the technique / skill / preparedness (2) measure the effectiveness of our assistance menu. In other words, if you spend a lot of time on variations and assistance work and get really strong on a diverse selection of exercises, but drastically decrease your frequency and volume on the competitive lifts, you may not get the carryover you are looking for when you pick back up on the main lifts. But maybe you would have, had you gotten strong on some new exercises AND stayed in practice on the main lifts. So long story short – keep the main lifts in your program at least once per week. Program them how you see fit, but make sure you stay in practice and train these lifts with adequate volume and intensity to at least maintain the status quo while you build your strength on some new exercises. #2 Account for the Novice Effect with New Exercises When you first hit a new exercise there is going to be a little bit of a learning curve with the new technique on the new exercise. But usually, once the trainee gets comfortable with the technique, the first 2-3 sessions with this new exercise result in some really big jumps in performance. Just a few weeks ago I had a client doing Incline Presses for the first time ever. We used 185 lbs for sets of 8 reps. By our third Incline Press session he was doing 225 for sets of 8 reps. This is a 40 lb increase in 3 weeks and predictably, didn’t do much to move his Flat Bench Press. That’s because those first 40 lbs of progress were learned and not earned!!!!!! Now over the next several weeks I predict we will progress much slower from 225 lbs to say 255 lbs. Jumps will be small, progress slow, and reps will be hard. So that next 20-30 lbs of progress will be much more earned strength and muscle mass and I predict it will have carryover to the Flat Bench Press. So moral of the story is that you can’t expect that initial huge leap in performance on a new exercise to immediately affect your primary exercises. You have to spend some time with the exercise and get into those hard sets and reps and really earn a 10-20% increase in performance before you can expect much carryover. #3 Rotate Supplemental Exercises Every 2-4 Weeks Supplemental movements are those exercises that are very close to the parent movements both in performance and in load. So things like Front Squats, Close Grip Bench, Stiff Leg Deadlifts, etc. Once an athlete is trained and practiced on a given exercise (i.e. he’s mastered the technique and gotten his initial novice gains) I like to hit the movement hard for short periods of time, take it up to 1-2 limit performances, and then rotate it out with another supplemental exercise. 2-4 weeks is an average estimate, and often I will rotate the supplemental movement out every week or keep the movement in there a bit longer, but 24 weeks is a good ballpark. So one good way to handle these movements coming in and out of your program is to treat the movement similar to how you would select your attempts at a meet. When you rotate a movement back into your program after a few weeks, use week 1 to “re-familiarize” yourself with the exercise. This is like your “opener” at the meet. This can serve as sort of a deload of sorts as well, as the previous weeks leading into this week would have been limit attempts on a different supplemental movement (you’ll see this in the example below). So if you have a previous Stiff Leg Deadlift PR of 365×5, then maybe week 1 of this current rotation comes back in with an easy-ish 345×5 (about 5% decrease). In week 2 – we’re aiming for a small PR of 5-10 lbs, so maybe 370-375 x 5. This is kinda how I treat my second attempt at the meet – usually aiming for a small PR. Depending on how that goes, come back in Week 3 and go for broke (like your 3rd attempt) and hit another PR of anywhere from 5-20 lbs based on the ease or difficulty of week 2. If you like the numerical RPE scale, this is a good place to use it. I use a subjective scale of easy / medium / hard. If week 2 is easy, go up 20, if it was medium go up 10, if it was hard go up 5. If it was LIMIT or you have missed reps, then record your new PRs and move onto the next movement. If after the 3rd week you still have a little gas left in the tank on that exercise – go up another 5-20 lbs and hit more PRs. Usually after week 4, I’d move onto a new exercise. I really like to avoid having missed reps or regression. I almost NEVER do resets on assistance work unless the trainee has a prolonged layoff from a given exercise. Instead, if we have a miss, regression, or a plateau on a supplemental exercise – we just rotate out to a new exercise and come back to this movement in a few weeks. It works better. Here is an example using two different assistance movements: Week 1: Stiff Leg Deadlift 345 x 5 Week 2: Stiff Leg Deadlift 370 x 5 (5 lbs over previous PR – medium) Week 3: Stiff Leg Deadlift 380 x 5 (hard) Week 4: Stiff Leg Deadlift 385 x 5 (Limit!!) Week 5: Goodmorning 205 x 5 (10% under previous PR – deload from week 4 limit sets) Week 6: Goodmornings 230 x 5 (5 lbs over previous PR, easy) Week 7: Goodmornings 245 x 5 (hard) Week 8: Goodmornings 250 x 5 (limit!) Week 9: Stiff Leg Deadlift 365 x 5 (5% under previous PR, deload) Week 10: Stiff Leg Deadlift 390 x 5 (5 lb PR, hard) Week 11: Stiff Leg Deadlift 395 x 5 (limit) Week 12: Goodmorning 225 x 5 (~10% below previous PR, deload) Week 13: Goodmorning 255 x 5 (5 lb PR) etc, etc. This type of planning is not limited to just two exercises rotated in and out. I’ve done this with clients with as many as 4 different movements, hitting each movement for 2-4 weeks at a time. Sometimes one of the exercises in the rotation hits a plateau. There are two things to do in this scenario…..(1) change how you train that exercise. In other words, change the set/rep scheme, add/subtract volume, etc. or (2) drop the exercise from your rotation and come back to it after a longer break. Oddly enough, sometimes training something less yields more progress than training it more. Not always, but sometimes this is true with assistance and supplemental movements. #4 Rotate Accessory Exercises Every 1-2 weeks The accessory movements are those exercises that are generally non-barbell, lighter load, and/or isolation type movements. Things like glute ham raises, leg curls, tricep extensions,, lat pulldowns, etc. I tend to rotate these movements out with even more frequency than the supplemental exercise menu – usually every week. So pretty much every time we do these exercises we are looking for PRs of some kind. It’s difficult to progress in load every time you do these movements, but there is usually some metric of performance you can increase. Maybe that is adding reps to your sets, adding sets, reducing rest between sets, etc. But prolonged weekly progress on a Cable Tricep Pressdown is difficult, so we’re going to hit it hard every time we do these movements, try and set a PR of some sort and then come back to it in a few weeks and hit another PR. On most of these exercises we’re going to be chasing some metabolic fatigue in the target muscle group so use the “pump” as an indication of how and when you need to change things up. If the exercise gives you a massive pump on week 1 and fades in week 3, time to switch things up. I think the pump is maximized when exercises are switched weekly. #5 Mirror the Competition / Primary Lift’s Sets and Reps and Intensity This is a little bit different way of doing things and doesn’t precisely square with some of the advice I’ve already given. Like I said in the intro…..lots of approaches can work, these are all different tools in the tool kit, just some things to think about, not prescriptions for life. So here’s what I mean. Let’s say you are doing my 3 week mini-cycles of 8s, 5s, and 2s on the main exercises. For instance, in Week 1 you will Bench Press for sets of 8, in Week 2 you will Bench Press for sets of 5, and in Week 3 you will Bench Press for sets of 2. When you do your supplemental lifts, I like to keep with the “theme” of the day in terms of rep range and intensity, and I select exercises that work best in that rep range. So in Week 1, we Bench Press for sets of 8, and then perform Incline DB Presses for sets of 8-10. In Week 2, we Bench Press for sets of 5, and then perform Weighted Dips for sets of 6-8 In Week 3, we Bench Press for sets of 2, and then perform Incline BB Presses for sets of 4-6. Then the accessory lifts pretty much always stay in the 8-15 range depending on the exercise. You certainly don’t have to do this, but it’s something that has worked well in the programming I run for my clients. If you want a more detailed example of how this works in an actual training program I would check out my KSC Method for Power-Building Program. Great Advice on Assistance Work This past weekend I went to a local power lifting meet – strictly as a spectator, for the first time in many years. But the opportunity to watch James Strickland Bench Press 700 lbs Raw was something the meat-head in me just couldn’t resist seeing first hand. Unfortunately James didn’t make his 700 lb goal but it was still a great learning experience to watch James and his coach Josh Bryant in action. While at the meet I heard a great piece of advice that I wanted to share with you – “If you continue to train small muscle groups as if they were small muscle groups…..they will remain small muscle groups.” Apparently the original source for the quote was IFBB pro Evan Centopani when he was being interviewed about his insane calf development. The gist of the interview was that when he stopped treating his calves as secondary body parts that got casually and haphazardly trained at the end of the workout – they started to grow. Now, I know that most of you reading this are not aspiring body builders and this isn’t an article on training the calves. However, even for (and maybe especially for) a strength athlete, there is much you can learn from changing your approach to training “secondary” muscle groups like the lats, triceps, low back, hamstrings, etc. How many of you work the big lifts hard, but when it comes time to hit your Dips, Lying Tricep Extensions, Barbell Rows, Back Extensions, Glute Hams, etc, etc, you just simply “punch the clock” and knock out your obligatory 3 x 10 or whatever with plenty of gas left in the tank on that exercise. If you even do the assistance work you had planned…….it’s half-assed at best. Always a few reps in the tank, always a few pounds left on the bar. Well stop doing that. The longer you train, the more valuable the role of assistance exercises will become in your training regimen. Over time it becomes more and more difficult to elicit the adaptive response we want from our training simply by hitting the Squat, Bench, & Deadlift on repeat. Sure, there is an almost infinite amount of volume / intensity / frequency arrangements we can tinker with but many lifters will simply go stale with this approach. Continual progress will require dedication to the training of the big lifts, but also to steady progress on the assistance exercises as well. Progress will mean that you have to push yourself on these lifts. You need to constantly be trying to add weight, add reps, add sets, and make these exercises harder and harder. When you go stale on one, switch it out and push another for a while. This is the best way I know of to add muscle mass and thereby strength. James Strickland is a perfect example of this. He didn’t build up to hitting 672 lbs on the bench press just by doing bench presses (this was his final warm up set this past weekend). Here is a guy that weighs 290 lbs that also does weighted dips with 260 lbs. He does chest supported seal rows with 405 lbs. The list goes on, but the moral of the story is that he treats the assistance exercises that work for him with as much tenacity and effort as he does his heavy bench press work sets. We can all learn from this. If you aren’t doing so already, and your lifts are not progressing, select a handful of assistance exercises and start working the hell out of them on a regular basis. Start where ever you are at with each exercise and every week hit the movement hard and try to add weight or reps. When you go “stale” on a movement, switch to a different exercise in that category, and then revisit the original exercise later in the year. If you aren’t sure what to choose, here is a quick guide that can help you narrow down your choices: 1. Supplemental Pressing: DB Bench Press, DB Incline Bench Press, Seated DB Press, Dips 2. Tricep Extension: Lying Tricep Extension (ez curl bar), Lying Tricep Extension (DBs), French Press (ez curl bar), Cable Pressdowns 3. Row: Barbell Row, Old School T-Bar Row, One Arm DB Row, Chest Supported Row 4. Hamstrings/Low Back: Romanian Deadlift, 45 or 90 Degree Back Extension, Glute Ham Raise, Lying Leg Curl, Reverse Hypers, Goodmornings Of course if you are already following some sort of assistance template then keep on keeping on, but see if you can’t pick up the intensity a bit and start hammering home some new progress on some of those exercises where you are currently just “punching the clock.” Are You Training to Heavy? (Part 1) You judge the effectiveness of your program by how often you are able to increase load on the bar, right? Right. But do we go heavy all the time, on every exercise, if more weight on the bar is the goal of the program? Not necessarily. I've talked a lot over the years about ways to regulate the loads on the main lifts with programs such as 3 day per week Heavy-Light-Medium programs and 4-day per week Heavy-Light Programs. And more recently I've been discussing the value of rotating Max Effort movements as a means of oscillating loads week to week by changing exercise selection. So today I'm not really talking about load on the main lifts....I'm talking about load on your accessories and assistance movements. Do we still want to take these movements heavy? The answer is YES......but within certain constraints. Heavy is relative to REP RANGE. I like to keep most small accessory movements in the 8-15 rep range, occasionally dipping below or going above, but 8-15 is a good ball park. This gives you plenty of volume if you work 2-4 sets of each movement, it can deliver a great pump, and keeps your joints healthier than banging away at everything with lower reps. So go as heavy as possible, but keep reps high. As a rule of thumb, I assign a range to a given exercise. And it varies by exercise. Might be 10-15. Might be 8-12. Might be 610. Or even 15-20. Lets say 10-15 reps for 3 sets. When do we add weight? When at least one set hits 15 reps, and no set drops below 10. Then add weight. Follow this pattern with whatever rep range you are working in. If you can't get 15 on any of your sets, then keep the weight the same on the next workout but try and increase reps. If you are dropping below 10 reps on your sets, then decrease the load so you can keep reps above 10. Oh.....and a really important detail......keep rest times consistent. 2-3 mins on accessories is good. If you don't keep track of this, it's hard to gauge performance. There is a big difference between 1 minute and 3-4 minutes. So stay heavy, but stay within the constraints of the rep range you assign to a given exercise. Copy & Paste the following summary somewhere........ Increase weight only when you hit the top end of that rep range with at least one set. Increase reps if you are within the rep range but haven't hit the top end yet. Decrease loads if you are falling below the bottom end of the rep range. Train heavy, but train smart!!!!! Are You Training to Heavy? (Part 2) Yesterdays email discussed the differences between just arbitrarily adding weight to the bar every week versus progressing within a given rep range. Which, again, might mean adding weight to the bar if you hit the top end of your rep range. And it might mean keeping the weight the same while trying to increase reps. And it might mean taking weight off the bar (or machine or dumbbells or whatever) if you are falling out of the rep range you want to maintain for a given exercise. I challenge all of my clients to push the boundaries on their accessory and assistance movements. I push them all every week to either chase more weight or more reps on a given exercise. That is how you grow. But again, this must all be done within certain constraints.......... Specifically, I'm talking about RANGE OF MOTION today. Assistance exercises are about working muscle groups. In a sense.....you are bodybuilding when you do assistance work. It can never be about moving the weight from Point A to Point B by whatever means necessary. Your form must be strict. You must establish a mind muscle connection with the body part you are working. And you need to take the muscle through the fullest range of motion possible when you do the exercises. Partial reps on a DB Bench Press are ludicrously dumb. The only reason to use dumbbells is because they offer you the ability to take the pecs through a more complete range of motion than a barbell. But yet I see guys all the time doing 150 lb dumbbells and stopping 6 inches from their chest. They'd get better growth by doing the 80s and taking them deeeep and holding the bottom position for a 2-3 count. Use a weight that allows for a full and complete range of motion. Learn to feel the muscle work. Get a pump in the muscle. Get some stretch under load! Once you can do that......then load it up!!!!! But never sacrifice the range of motion for more weight. Go Deep!!! Intermediate and Advanced Training: A Few Ideas Starting Strength is on a roll. The method is growing in popularity, and as it does, more people flow through the Novice pipeline and end up as Intermediate and even Advanced lifters than ever before. Once a tiny fraction of the training population, post-novice trainees now comprise a rapidly expanding section of the market for training information. It is important that the logic and clarity of the Starting Strength approach to Novice programming be maintained as these lifters enter into more complex stress/recovery/adaptation environments. Complexity is seductive. There is something about it that the human mind finds attractive, as though harder to understand/more moving parts/some assembly required equals Better. Lifters are not immune, as the near-universal tendency to prematurely advance to unnecessarily complex programming demonstrates. And yes, it matters. Progress will still be made on programs that are satisfyingly complex and advanced-lifterly, but if we can make progress every workout instead of every week or every 4 weeks or 8 weeks, the arithmetic indicates that the progress is faster. Most people’s training eventually gets interrupted by circumstances outside their control, and if they’re stronger when this happens – because they made faster progress when they had the advantages novices have – the interruption leaves more on the table after the layoff than it otherwise would. This also applies to post-novice programming. The same principles that allow the efficient management of the stress/recovery/adaptation (S/R/A) cycle apply even when the cycle no longer operates in a 48 to 72-hour period. In the absence of a convincing argument against faster progress, it should be the default assumption. And the fastest progress will always be obtained by 1.) basing your training program on data collected directly from your training, and 2.) adding complexity to your training only when necessary and as little as possible. PRs are the measure of progress, and these two principles, when properly applied, result in PRs with the maximum frequency your level of training advancement permits. Train Based on Your Training Your training needs to be based on the training itself, not a performance. So we’re all on the same page here, training is the process of accumulating a specific physiological adaptation or adaptations necessary for improved performance in an athletic event. Training is composed of a series of workouts that progressively and intentionally increase the stress from which recovery provides the adaptation. Training takes place over time, and it is carefully designed to produce the type of stress necessary to generate the adaptation specific to the performance for which you are training. The performance is a point in time when an athletic contest will occur and for which an athlete prepares to demonstrate the best effort possible under the scrutiny of judges or against direct competition. The performance tests the limits of the preparation provided by training. (In contrast, practice is the repetitive execution of movement patterns that depend on accuracy and precision, to develop the skill that will be demonstrated in the performance.) Training is therefore a process, and performance is a demonstration of the results of the process. It is obvious that Novice programming works because of the process of adding 5 pounds to the squat every workout until this process cannot continue to generate improvement. Novice training is not based on a performance, because there has been no performance – no test, no attempt to find the limit of ability. Rather, the novice determines his first workout weights by titration up to a heavy-ish weight that still permits absolutely correct form for 3 sets of 5, and then he adds 5 pounds to that weight for 3 sets of 5 for the next workout. This pattern continues until it cannot be sustained, with each workout based on the accumulated adaptation produced by the process as manifest in the previous workout’s numbers. The novice calculates his training loads based on his previous training – not a performance – and the process works because of the reliability of the S/R/A cycle and the trainee’s diligent attention to driving the process efficiently. He rests enough between sets and between workouts, his incremental increases in training load accurately reflect his proven ability to do the work, and his diet and sleep effectively supports his training. For the Intermediate trainee, the same principles apply: effective training must be based on the process that generated the adaptation – the selection of loads and workouts that produced the accumulation of strength, just like those which formed the basis of the novice progression that led up to the now-more-advanced state of adaptation. The Intermediate should not assume that just because he’s no longer a Novice, the basis of his training load selection must change. The Conventional Wisdom It is common for Intermediate trainees to “fall off the wagon” and default to the conventional wisdom, which holds that a training cycle must be based on new PRs set at a meet or on a Test Day – a performance, as opposed to the training history that produced the need for Intermediate programming. The conventional wisdom holds that the meet PR forms a new datum line, and that training loads should be calculated as percentages of this PR. I have been told by sources I trust that some people will go so far as to use a “1RM calculator” table in order to estimate their 1RM for the express purpose of using a program based on 1RM percentages. Complexity rears its beautifully seductive head. In reality, a PR at a meet is the result of the same processes that produced the training PRs leading up to the meet – which the Intermediate lifter experiences every week – with several other variables added in, factors which are not present during training and which therefore do not apply within the workouts – where the actual work that produces the adaptation will be done. Some people feed on the adrenaline of competition, some are distracted by it. Meet directors have ways of fucking up your performance with inadequate staffing, shitty equipment, delays, misloads, and irritating displays of incompetence. Perhaps making weight in a weight class you don’t belong in adversely affected your total. Maybe it’s just a plain old Bad Day. Sometimes your Test Day at the gym doesn’t go as well as you’d hoped it would, for many of the same reasons. All these factors contribute to a sub-par performance. And sometimes, on rare occasions, the meet runs so well and things fall into place so perfectly that the circumstances can’t be duplicated in your own training environment. You taper your training away from basic work toward peaking for the performance. And then you take a 2-week layoff, to “rest” and otherwise detrain. All these performance scenarios, your taper, and your well-deserved layoff almost always generate bad data that cannot be relied upon for planning the resumption of training – data that will not accurately reflect what you can do or should do now, especially if it is used to project numbers based on a percentage of the performance number. A snapshot from a single day’s performance is a myopic approach to a long-term project. This is why a meet PR and a true 1RM are seldom the same thing, and why a 1RM test/performance is irrelevant to your future programming. The Starting Strength Approach The simplicity and elegance of the Starting Strength method is this: plan your training on the previous workout if you’re a Novice, the previous week’s workouts if you’re an Intermediate lifter, the previous month’s workouts if you’re an advanced lifter. Project your programming forward based on the trends that develop within these training periods, and on what you know about how you respond to the stress of training, how best to facilitate recovery, and how the adaptation affects subsequent workouts. If you’re a Novice, just go to the meet and see what happens. If you’re an Intermediate, do the meet in lieu of your heavy Friday workout. If you’re an advanced lifter, plan for the meet as far out as your training advancement requires. Then everybody resumes training after a meet using the most recent data from training before the meet, not data from the meet itself, since training data is better-quality data for training. This is not to discount the value of the performance itself. Assigning yourself the task of getting ready for a meet and executing a performance under pressure adds urgency and value to your training. It focuses the mind. And the performance itself provides very highquality experience that comes in handy at the next meet. In this sense the performance itself is a form of practice for subsequent competition, and the data obtained will include such things as attempt timing, the conversion of training loads into 3rd attempts, the proper selection of 1st and 2nd attempts, the effects of varying rest periods on your attempts, how you deal with misloads and timing errors, etc. But the data obtained during a meet is best applied to the next meet, not to your training.Your performance at the meet is not the determining factor of your level of training advancement, even though your level of training advancement may well determine what you do immediately after the meet, i.e. the necessity of a deload period. Training data and performance data are two separate data sets, and are best used that way. Train according to your training data and compete according to your meet data, and the results will not be distorted by inapplicable inputs. The Lowest Effective Dose of Complexity When considering our Novice lifter’s training status, it’s important to keep the actual length of his “training career” in perspective. A trainee with 6 months of experience may no longer be a Novice (as defined in PPST3 with regard to level of training advancement), but anybody who has only been training 6 months is still a beginner in terms of experience under the bar. As any experienced lifter knows, 6 months of training only scratches the surface of what a lifter has yet to learn. The aforementioned near-universal tendency to attempt to train past your level of actual training advancement is an example of inexperience getting in the way of progress. A Novice who has been accumulating strength by adding weight to his squat every workout for 6 months, who has a couple of tough workouts, and who then decides that Novice programming has lost its allure will often jump into a program designed for lifters much more advanced than he is. This is an example of selecting a program to emulate your Heroes, not training based on an accurate assessment of where you are now and an analysis of the best way to improve from here. Since trainees using post-novice programming have by definition exhausted their ability to apply stress sufficient to cause an adaptation and be recovered from it in one workout. In other words, the overload event – the operative unit of stress in the S/R/A cycle – takes more than one workout to administer, perhaps a week, eventually a month or more. As the lifter progresses, the program will become more complex than the novice program. But no more complex than is absolutely necessary – the lowest effective dose of complexity principle should be followed. If a week-long overload event works, don’t use a month, or two months. The closer you are to Novice programming, the shorter the overload event will still be. Disregarding this causes time to be wasted, and if approached incorrectly will cause absolutely unnecessary levels of detraining. For example, a 35-year-old Novice finishes up a productive squat LP at 375 x 5 x 3 – he’s tried 380 x 5 x 3 and missed some reps on his last 2 sets after a previous reset. He should back off to 355 x 5 x 5 for his first squat workout using the 4-Day Split, an excellent programming choice for a guy in this situation. The 4-Day Split represents a change in training schedule from the 3-day Novice progression, while retaining the simple logic of regular progression. The lifts are trained only twice a week, the workouts are shorter, and recovery is easier, very important since recovery limitations were why the change was necessary. But intensity is preserved, progression moves from 48 hours to weekly, and PRs are only a few workouts away. 4-Day Split Upper Body – Monday/Thursday Lower-body – Tuesday/Friday Bench or Press Chest/Shoulder assistance Squats Pulls Lats Arms Again, PRs are the point of training: if you’ve stuck with this long enough to switch from Novice to Intermediate programming, lifting heavier weights was your motivation for doing so. The last thing most people in this situation should do is change the entire emphasis of the programming – moving from the simple elegance of the Novice LP to Matveyev Undulating Periodization or Verkoshansky Block Training or Smolovninskyevov Eludium Q36 Space Modulator Oscillating Phase Determinative Training or anything else developed for Elite Russian Athletes. This will be necessary eventually, but certainly not a few months after you start training. On Volume Volume training seems to be gaining in popularity. Backing off from 375 to 305 for more reps, sets, and higher volume while adding more squat days to the program would actually be detraining in intensity to favor increased volume, and “junk reps” do not drive a strength increase in anybody except a baby novice. Volume outside the context of tonnage is meaningless: 8 sets of 6 reps at 50% is high volume. What often gets lost in discussions about volume is the fact that as a lifter moves upward through the levels of training advancement, and as the overload event obviously becomes longer, volume is calculated across the now-longer overload event. The Novice overload event is a workout, so the volume and tonnage are calculated for the workout. Intermediate trainees are using a week's training as the overload event, and the math reflects this time period. A week's training in a Novice program and a week's training in Texas Method are not equivalent overload events – the Novice week is 3 overload events, and the TM example is one overload event. As every lifter progresses through the levels of training advancement, the volume in each increasingly-long overload event is higher than it was in the previous programming iteration as a natural consequence of the changing nature of what constitutes the overload. It is true that hypertrophy is the only mechanism – after an initial co-development period of neuromuscular efficiency improvement – by which a muscle increases in strength. It is true that bodybuilders who train for hypertrophy use higher reps, maybe 8–12, more sets and less rest between sets (using lighter weights than 5s and 3s because you can't do high-rep volume with very heavy weights), which results in higher rep numbers for each workout. But it is also true that as your deadlift increases from 500 to 600 using 5s, 3s, 2s, or singles across weekly and even monthly overloads, hypertrophy occurs to facilitate the adaptation, and increased volume has been a contributing factor. You’ll have to decide whether you want to train light bodybuilding volume for hypertrophy to drive strength, or train for strength and obtain hypertrophy as the facilitating adaptation. I suggest that the latter makes more sense to most people. It’s also important to note that avoiding exposure to higher-intensity training in favor of lighter volume at this point in a lifter’s career robs him of critical lessons that all good lifters must learn. Straining against loads in excess of 90% does not merely display and build strength – grinding out heavy triples, doubles, and singles is also a skill. And skills must be practiced. You already know how to lift light weights – they're called “warmups.” There is a psychologically and even an emotionally developmental component to unracking and lowering a weight you aren’t sure you can actually squat. Inexperienced lifters must learn to manage fear and apprehension, and develop the skill required to focus through it. In my four decades on the platform with clients and lifters, I have observed thousands of people who prematurely racked a heavy set of squats or set down a heavy deadlift before it even got stuck on the way up. All experienced coaches have heard inexperienced trainees say, “I couldn’t have done another rep!” when we know from experience they had 2 or 3 more reps left on the bar. Experience Experience. Experience. Experience. Perception is based on it. Accurate assessment of your subjective perceptions is utterly dependent on it. Baby lifters don’t know how limit work feels because they have never reached that level of intensity. They don’t know that warmups sometimes feel like shit right before they find themselves able to do all the programmed work sets. Experienced lifters set PRs under the same conditions – the warmups feel like shit, they gather up their balls, try the PR anyway, and it goes up. Not as often, the opposite situation occurs: warmups feel better than they’ve ever felt, and the work sets are just not there. Experienced advanced lifters learn to be objective about their capacities by experiencing actual failure under the bar. You cannot learn to be objective about your perceived capacity under the bar without the occasional failed attempt. While failure is not a desirable occurrence, it is the unavoidable consequence of training at the limits of your ability. And each time you fail, you learn what it feels like and what led up to it, and you get better at accurately analyzing your efforts under the bar. By the same token, lifters also learn important lessons when they complete a rep they didn’t think they could make. There is a lot to be said for grinding out a heavy rep, taking 10 or 15 deep breaths, then digging in and completing another one. I have written about heavy sets of 20 squats before, and I think the lesson learned from reps 18, 19, and 20 is far more valuable than the training effects of this horrible program. Having never been exposed to very heavy singles, doubles, and triples as a novice, early intermediate training is an excellent place to introduce this new training variable. It’s a catalyst for continued progression – physiologically and psychologically. More sets at lighter weight doesn’t teach you anything you don’t already know. Using the 4-Day Split example, the first week’s volume day’s 25 reps at 355 is a 10-rep volume increase that has you handling within 6% of your previous intensity on volume day, with work tonnage at 8875 pounds. It’s both enough room for a run-up to fresh PRs and heavy enough to maintain the strength adaptation you’ve trained months to obtain. Then, intensity day at 380 x 5, the same weight you’ve done for 5 before the changeover, sets the stage for the intensity and the “grind” practice necessary for continued progress. The reduction in squat frequency from 3x/week to twice increases the recovery potential from the higher-volume workout while maintaining your strength for heavy weight. A comparison of the Novice Linear Progression Squat overload event and the Intermediate 4-Day Split Squat overload event. Advanced lifters often use longer periods of higher volume at lighter weight. Tapering up to PR intensity is necessary for athletes who are adding only 10–15 pounds to a lift over an 8 to 10-week period. If high intensity is the end of the taper, high volume has traditionally been the start of it – a deload period after a long cycle of high intensity and low volume. But if you were making 48-hour jumps of 2.5–5 pounds as recently as a couple of weeks ago, the jump into several weeks of lowered intensity for the sake of a training volume adaptation will be an unsatisfying, and more importantly unnecessary, regression into detraining. In this case the “lowest effective dose” refers to the amount of deviation from what has previously worked well. At some point in a lifter’s training it will be necessary to get complicated, and to program in periods of time longer than were previously used, because the closer you approach the limit of your physical potential, the longer it takes to make a smaller amount of progress, the more complex the process will be, and the greater the likelihood of an injury because of the proximity to your absolute limit and your high level of motivation to find that limit. But actively seeking a level of complexity that is not only unwarranted but unproductive is a waste of time and potential strength. Training is more productive if it remains as simple and straightforward as possible, and this means the absolute least amount of deviation possible from the task of setting new PRs as often as possible. Pulling for Speed: A 6-week Squat & Deadlift Cycle If you aren’t an Olympic Weightlifter, but you love using the Olympic lifts in your training, then I think you’ll love this training program. I’ve written this out for about 5 or 6 private clients of mine this year and it has worked like a charm each and every time. While that isn’t a huge sample size, in general if something works really really well for 5 or 6 people it’s probably a keeper of a program. As I was writing up a program for a new online client of mine this morning, I included this little Squat & Deadlift cycle as part of his overall program, and I thought “what the hell!” let’s throw this thing out there to my readers as food for thought and a thank you for supporting my blog! Who is this program for? I would recommend this program to an intermediate or advanced trainee who has some skill with the Power Snatch and Power Clean…..or at a minimum, just the Power Clean. I’m an advocate of the Olympic lifts, but only for those who can kinda naturally “get it.” If you just suck at them, then you probably don’t get much out of them. “Suck” doesn’t necessarily mean “weak” at them. It just means you have very poor skill, timing, and coordination. If you don’t have that, you probably won’t get real strong on these. If you are reasonably proficient at the lifts, then you can get stronger at them, even if you aren’t strong on them now. Overview…… My experience with this program has been part of a 4-day split routine (2 days upper / 2 days lower). In general, the routine is just kind of a mish-mosh blend of some concepts that stem from the Texas Method, the Westside Barbell method, and a healthy dose of my own influence and experience. Basically you’ll have one lower body day per week that is higher in Intensity and lower in Volume and this day alternates weekly between a Squat emphasis and a Deadlift emphasis. The second day of the week is higher in volume and lower in intensity. Both days have a Speed / Power element in the form of Dynamic Effort Squats and Pulls and/or Power Cleans and Power Snatches. The Program…. Week 1 / Day 1: Back Squat – work up to 85% x 3+ Speed Deadlift 70% x 3 x 8 (8 sets of 3) Week 1 / Day 2: Speed Back Squat or Box Squat 5 x 5 x 70% Power Clean 15 x 1 (30 sec btw reps) Week 2 / Day 1: Power Clean – work up, in singles, to a miss. Go down 10% and work back up to a miss. Done. Deadlift – work up to 85% x 3+ Front Squat 5 x 3 (5 sets of 3) Week 2 / Day 2: Speed Back Squat or Box Squat 6 x 4 or 8 x 3 @ 75% Power Snatch 15 x 1 (30 sec btw reps) Week 3 / Day 1: Back Squat – work up to 90% x 2+ Speed Deadlift – 75% x 3 x 6-7 sets Week 3 / Day 2: Speed Back Squat or Box Squat 8 x 3 or 12 x 2 @ 80% Power Clean 15 x 1 (30 sec btw reps) Week 4 / Day 1: Power Clean – work up, in singles, to a miss. Go down 10% and work back up to a miss. Done. Deadlift – work up to 90% x 2+ Front Squat 5 x 3 (5 sets of 3) Week 4 / Day 2: Speed Back Squat or Box Squat 5 x 5 x 70% Power Snatch 15 x 1 (30 sec btw reps) Week 5 / Day 1: Back Squat – work up to 95% x 1+ Speed Deadlifts – 80% x 3 x 5-6 sets Week 5 / Day 2: Speed Back Squat or Box Squat 6 x 4 or 8 x 3 @ 75% Power Cleans 15 x 1 (30 sec btw reps) Week 6 / Day 1: Power Clean: work up, in singles, to a miss. Go down 10% and work back up to a miss. Done. Deadlift – work up to 95% x 1+ Front Squat 5 x 3 Week 6 / Day 2 Speed Back Squat or Box Squat 8 x 3 or 12 x 2 @ 80% Power Snatch 15 x 1 (30 sec btw reps) Tips….. At the end of 6 weeks you can test for new 1RMs…..OR……if you want to avoid testing you can probably safely “assume” a small increase in 1-rep max and just go back through the cycle and bump all your poundages up 5-10 lbs as you see fit. This works too. Although if your assumption is off, it can screw you up pretty good for next cycle. Aim conservatively. Rest time for speed work on the Squats and Deadlifts is 1-2 minutes. Move the bar with good speed, but do not get out of control in the name of speed. Maintain good mechanics FIRST and then aim to put a little more juice into the bar on each rep as you can. Lower Body Assistance? I typically add in maybe 2 assistance exercises on both sessions for a little added volume or simply to satisfy the needs of a client who wants to do things like ab work, single leg work, glute ham raises, etc. So if that’s you’re thing you can add it in, if you are a minimalist, leave it out. I’m not really into the debate on how much this stuff helps or doesn’t help particularly for athletes training for sport. This is a very difficult thing to measure or split test. I’m of a mind that if you keep the volume and frequency of this stuff fairly moderate, then at worst you are just wasting time. But I think that it does help, albeit marginally. Look at it like this, getting stronger on glute ham raises is probably a good thing. There is no downside to being stronger on an exercise. And if you can do that in 10 minutes per week knocking out, say 3 sets of an exercise…..even if it is wasted time and energy, it is a small amount of both. To start with I usually add in 2 hamstring exercises per week – 1 knee flexion (glute ham raise or leg curl) and 1 hip extension (RDL, SLDL, 45 degree back extension, etc) – one exercise on each day. I’ll give my usual disclaimer / caveat here at the end that sets and reps and even exercise selection are of course subject to change and individualization to a degree. Adding or subtracting a set here or there is fine. Increasing or decreasing intensity +/- 5% here and there is fine. Sub out front squats for 5×3 with high bar squats for 3×5 – fine. Try not to get lost in the tiny minutia and miss the broader structure of the program. I have used this almost exact program with several people and it’s been kicking ass so don’t rewrite the thing so much that it becomes a different program entirely. If your squatting and pulling is stuck in a rut, this might be something for you to try. Why & How to “AMRAP” Effectively (4 Methods) So most of us have come to know and use “AMRAP” as a pretty common acronym in the strength and conditioning world, but in case you don’t know “AMRAP” stands for As Many Reps As Possible. We used to just call this “taking a set to failure.” But with all things terminology changes and training to failure has kind of earned itself a negative connotation for better or worse. So we’ll go with the times and talk about the most effective strategies when using an AMRAP set or sets in your programming. So why do AMRAP in the first place? Well, good question and some coaches argue against it and not without merit. But there are two main reasons why one might do an AMRAP set – testing and training. An AMRAP set can be an effective way to run a “test” if you want to gauge where your strength is at during a given training cycle or perhaps at the end of a training cycle. This would be in lieu of testing a heavy single. If you want to gauge absolute strength, singles are the most reliable method since you are basically cutting right to the chase. If you want to see how much weight you can lift….then see how much weight you can lift. But this has it’s draw backs. Mainly taking out a random 1RM on the Squat, Bench, or Deadlift is fatiguing as hell and can screw up a training cycle when you time it wrong. Others might want to avoid singles because they have previous injuries they don’t want to provoke with extremely heavy weight or perhaps they train alone and prefer to not handle weights on a squat or bench press that they might get pinned with. In these cases you can use an AMRAP set as a metric for testing strength. I’d suggest using weights in the 3-6 range for these types of AMRAP sets as they tend to be more reflective of actual 1RM strength than say a 10-rep max which has a major conditioning / endurance component to it. I’ve seen some brutally strong men who probably didn’t have a great 10rep max….mainly because they don’t train with 10+ reps. Given a few weeks of specific training they COULD have a big 10-rep max, but they simply lack the stamina to get there. So for this reason, I like lower rep sets. So for instance if you know your previous best Bench Press at 275 lbs is 3 reps, then AMRAPing 275 and hitting 4 or 5 reps is a good indicator that you have gotten stronger without having to test a 1RM. If you REALLY want to know your 1RM – then test a 1RM. But if you just want to know if you are getting stronger….adding reps and/or weight to a 3-6 rep max is fine. Training w/ AMRAPs I do actually like AMRAP sets when used appropriately. There is always debate on how total volume, training to failure, fatigue, muscular damage, and metabolic stress factor into muscular hypertrophy. Most of the current thinking tends to lean towards total volume as the primary driver of hypertrophy while other mechanisms are considered to be irrelevant or of lesser importance. So in terms of hypertrophy does 405 x 10RM yield to more gains than 405 x 5 x 2??? Volume is the same, but the stress is a bit different. I’d argue that the former is more powerful than the latter…….in the short term. In the long term, the 405 x 10RM is a helluva difficult thing to perform week in and week out, whereas 405x5x2 can probably be improved upon more linearly by adding sets/reps/weight more easily and in the long term you can argue that 405x5x2 is more powerful than 405x10RM. So I like AMRAPs, but sparingly and I tend to use them on ASSISTANCE AND SUPPLEMENTAL work far more often than I do with the primary exercises. I tend to rotate assistance and supplemental work in and out of the program on a fairly regular basis and for this reason I find AMRAPs work great. I get the most out of the exercise as I can NOW! and then I switch it out for something else and come back to it in a few weeks. FOUR WAYS TO AMRAP If you are just doing a single set of an exercise for an AMRAP then it’s pretty straight forward. Typically I’ll program this for a client as a single set back off for max reps, either with the parent exercise, or as a slight variant. For instance, on the Deadlift I might have the person work up to a heavy single for the day and then back off to 80% and hit an AMRAP of between 4-6 reps. On the Deadlift example, I only use Deadlift AMRAPs after a heavy single. If I have the client work up to say a heavy set or sets of 3-8 reps (the “training reps”) then I might do their single set back off AMRAP as a Stiff Leg Deadlift, RDL, or Deficit Deadlift. So maybe they Deadlift for 3 sets of 5 and then hit an SLDL for an 8-10RM. Or maybe I’ll have them Bench for 5×5 and then hit a close grip bench AMRAP for a set of 810. etc, etc. I believe these types of sets go a long ways towards building muscle mass and work capacity. If I want to do an AMRAP for multiple sets there are three main ways to go about this. First is to AMRAP the first set and then AMRAP out the subsequent sets as well. Lets just assume 3 work sets of Dips. In the simplest version of this, you’d perform an AMRAP set of Dips and then rest for a set period of time that allows for complete or at least mostly complete recovery. We’ll say 2-5 minutes of rest between sets. What might be common in this scenario is a set of 15, a set of 12, and a set of 9. Basically the trainee will always hit the biggest number on the first set and then lose some reps as he goes. The second option is to AMRAP the first set and then rest very little and hit a bunch of very “small sets” until you reach some sort of cut off point in terms of reps or sets. There are several popular iterations of this. Currently “MYO-REPS” (credit to Borge Fagerli) are popular. With Myo-Reps the trainee might do a max effort or semi-max effort set of say 10 reps and then rest about 10 seconds and bang out 5-10 more sets of 2 reps with 10 seconds between reps until the trainee hits a total volume of between 20-30 total reps. This is similar to the DoggCrapp method which has been around since the early 2000s. Dante Trudel was epically successful with his clients (and himself) and created an entire bodybuilding system out of “DC” sets in which the trainee hits a max effort set (usually between 6-15 reps) and then takes a bit longer rest, usually in the form of 10-20 big deep breaths (about 30-40 seconds) and then hits another set to failure. The trainee then repeats this process one more time. The result is 3 sets done in quick succession. Usually about a 50% loss in capacity is normal. So it’s normal for a DC set to go from 8 to 4 to 2. Far less volume than the My0-Reps approach, but the weights are generally far heavier. The third option, which I often use with my clients is to perform two sub-maximal work sets and then have them AMRAP a third set. John Scheaffer of GreySkull Barbell uses a similar format in his version of his novice linear progression with the Squat, Bench Press, and Press. I don’t use this approach much with my clients with the main exercises, but I do it all the time on assistance exercises. For instance, if I’m having them perform a Dumbbell Bench Press I might have them do 2 sets of 8 with 75 lbs with maybe a 2-3 minute rest in between. On set 3, I’ll have them AMRAP out a set and hopefully hit around 10-12 reps to failure. Having a detailed history of past performances is critical with this method so you have an idea of what rep-max to shoot for on set 3 and how many reps to use on sets 1 and 2. I’ve found that this method allows for more overall total volume with meaningful weight, but still getting the benefits of taking sets to failure, creating fatigue and metabolic stress. I find potential benefits in all of these methods and potential risks in all of them as well. These are just some ideas for you to think about in your own training, as in all things training, there is usually more than one way to skin the cat. 4 Ways To Get More Consistent You’ve heard it from me and others 1,001 times right? We love to get way back in the weeds as it pertains to the details of programming and training, but for those of you who have been in the game for any length of time already know…..consistency and effort trump all. I don’t care what program you follow, what coaches you respect, and what lifters you idolize…..none of the details of the program you follow matter a lick if you aren’t consistent with your training. And most people aren’t unfortunately. One of my roles as a coach is to help people stay consistent by setting them up within a structure that is most likely to breed success in the short and long term. This is part of the “art” of coaching. Sets/reps/frequency/intensity/exercise selection, etc all have to be in alignment with the lifters level of advancement, the lifters goals, but also the lifter as a human being. People bring their personalities with them into the gym. And to the degree possible (i.e. we aren’t going to completely sacrifice results and principle) we need to accommodate this in order to get the most out of our clients. When I start work with a new client I don’t just ask them about their goals, I try to get a sense for who this person is as an individual. A Mechanical Engineer will typically have a different approach to training than a Serial Entrepreneur. It’s two different personality types and this influences training to a degree. So this brings us to point number one…… #1: Do What You Like To Do….Not Just What You Need To Do Fact of the matter is that there are a lot of different ways to train that are effective. Most of us have a preferred “style” of training that suits us best. Some of my clients love order, structure, and repetition. Many of these types of clients were drawn to the Starting Strength Program because the simple structure of the program was appealing to how their brains are wired. As intermediates these types of trainees will likely prefer programs that are similar in structure. 3 days per week of full body workouts are a good choice. Simple Heavy-Light-Medium or Texas Method Programs are a good idea. Pre-set templates are also a good idea. These types of trainees tend to operate well when there is structure provided and not too many decisions have to be made “on the fly” and there aren’t a lot of new variables to constantly learn and manage. “Loose Programming” is often how I train my clients at the gym. I have a plan and a structure but I’m constantly adapting and modifying as we go. Some extreme Type A clients hate this approach and do better in a format where they can operate off a pre-determined 12-week Spreadsheet. This is opposite my own personality, but that is irrelevant. A good coach understands his clients without projecting his own personal biases onto his clients. There are of course drawbacks to operating with extreme rigidity, but there are positives as well. For certain clients the biggest positive is the relative security and confidence they have in a well thought out plan versus the lack of confidence and security they have in a loose plan that is constantly evolving and changing as they go. When security and confidence are lacking then effort will be sacrificed. Trust me – people do not train hard on plans they don’t like or trust. And when the effort is not there, then neither will the results. And that’s when people start Program Hopping. This is a guarantee of no progress. The other side of the coin is the guy who just can’t do rigid. He needs some variety. Split Routines work well here. Split Routines typically give our lifter the structure he needs at the front end of every workout with dedicated work on the major barbell lifts, but also give him opportunities at every session to experiment and chase whims. If you don’t build this into the program the client will do it anyways!! So best build it into the program!!! Split routines generally get the lifter his volume in with a hefty dose of assistance exercises rather than repetition of the basics over and over again. There is pros / cons of either approach, but that is a debate for another time. The larger point is that the higher assistance volume type of routines (often upper/lower or body part splits) fit certain personality types better by giving them opportunities for more experimentation with different exercises and protocols. Typically the full body type approach has the lifter training like exercises more frequently with only a day or so of rest in between sessions. In these types of programs the lifter and coach have to be very careful about overdoing things as we have to keep in mind that more of the same is coming in about 48 hours. Haphazardly adding new exercises or experimenting with some crazy new rep scheme can wreck our next workout. With the split routine we typically have more days of rest between similar sessions. This makes the handling of all the relevant variables much less complicated. Overdoing things a bit or experimenting with new exercises or set/rep schemes is typically less consequential when you have more days to recover between sessions. Below you’ll find links to a few programs I offer that suit different personality types: If you like rigidity and the structure of a 3-day per week full body workout you might like the following programs: The Classic Heavy-Light-Medium Program The Garage Gym Warrior Program (A Cyclical Heavy-Light-Medium Program) The KSC Texas Method If you like variety in your programming you might try: The KSC Method for Power Building The KSC Method for Raw Power Lifting #2: Train More……..OR……..Train Less Talking out both sides of your mouth again, Baker! Yep. I am. Because I know from having coached hundreds and hundreds of clients that trying to conform to a routine that doesn’t match the rest of your life just won’t work to keep you consistent over the course of the coming year. Time is always a problem for busy adults with careers and families. Even people with the time to train often struggle with one of two options: Do I train more often, but with shorter sessions? Or train less often but with longer sessions? There really is no right or wrong answer. Adapt the program to fit around your work and family schedule. If either of those two things are getting negatively impacted by your training, eventually your training will slide. So maybe you need to just hit ONE major lift 5-6 days per week. Or maybe you need to consolidate 3-4 lifts into a 2-day per week program. Or maybe it’s somewhere in the middle. Just keep in mind BOTH ways can work. BOTH ways do work. So pick which one works for YOU and run with it. Keep your life in balance as best you can and you will enjoy your training more and stress about it less, giving you time to focus on work, family, and training in the appropriate ratios. #3: Schedule Your Year, Program Around Obstacles At the beginning of every year I suggest that each of you take a birds eye view of your calendar and try to get a feel for how your training will be impacted by events that are inevitably going to impact your training. Most of these big events are work related travel or vacations. If you KNOW these big events are coming, plan your training accordingly. It drives me bonkers when I get an email from someone who starts one of my 12 week programs KNOWING they have a week long camping trip right in the middle of the it!!!! Schedule your testing or peak weeks BEFORE these events occur, and if you want to follow a rigid 8, 12, or 16 week program, don’t stick a vacation right in the middle of it. Plan to run these types of programs during the times of year where you can train uninterrupted to the extent that is possible. For most people January – April are productive as is Sept – November. These are good times to try and plan to work through a structured program and potentially run a test or mock meet prior to summer travel or the holiday season. If you have periods of the year where you just can’t be consistent (summer vacation months, military training, sports seasons, etc) then I’d suggest you learn about Conjugate Training or other methodologies that allow you to train effectively without any long term rigid plans. I have articles on this Blog site about Training Without A Plan and Annual Periodization. They’re worth the read. #4: Find Accountability Most of the clients I work with online train alone in their garage or basement gym. Training in this environment is great for convenience and for avoiding the hassles of a crowded gym. But at times it can cause some people to struggle with consistency. If your home gym is too close to your home office or your wife and kids are always dragging you away from your workouts then your training sessions won’t be as therapeutic as they ought to be. And of course, when you train alone – who knows when you miss sessions? Having the accountability of a coach, a training partner, fellow gym members, or even an online community can help hold you accountable to your training if this is an area where you struggle. Figure out a way to build something into your training life that holds you accountable to other people. Maybe you training in your home gym Monday – Thursday but Friday nights you go to the local barbell gym and Deadlift with a group of fellow lifters. If it’s a good environment it can help spark enthusiasm into that Friday night Deadlift session that you otherwise dread. There are now thousands of online communities you can plug into and find good people to interact with and this can also help. I’ll go ahead and plug my own service here with the Baker Barbell Club Online. Some of the things we offer that help people stay accountable to their training are: Done for you weekly programming with TWO different tracks: A rigid Basic Barbell track and a highly variable Power-Building Track. Or some members do their own programs or one of my templates A highly engaged interactive Facebook Group where you can discuss the programming, get video form checks, and troubleshoot your own training A super positive and informative Private Forum where you can participate in several Q&A forum with me and other members and a place to keep your training log. So if 2018 wasn’t your year for training, then hopefully 2019 can be a better more consistent year. Implement a few of these strategies and see if you don’t get a better result. Case Study: Exploding Bench & Overhead Press Numbers on an Underweight Male So this case study is not meant to be read as any sort of authoritative, declarative, or definitive statement on “Bench & Press Training for the Underweight Male.” Instead, this article should be taken for what it is – a case study of a single individual who is training with extraordinary results using a specified set of methods. The fact is that many of you may try these methods and not see the same results that Jackson is seeing. You may have far better progress using the exact set of programming methods that were NOT working for Jackson in the months leading up to his sudden leap forward. Jackson is a hardgainer to say the least. He’s young (24), he’s got a naturally fast metabolism, he’s busy as hell (a student at one of the top law schools in the country), and he admittedly does not do everything possible outside of the gym to ensure he’s recovering and growing. Probably like a lot of you. Most of the time, for a guy that fits this mold, I’m going to prescribe a program for the Bench and Press that is fairly high in frequency and total volume. Most of the time, it’d be something like Benching on Monday & Friday and Pressing on Wednesday or Wednesday & Saturday. Sets and reps vary with the individual, but in general with the underweight genetically average young guy I lean towards a program that favors volume. Heavier guys, guys who have been training for many years, and those with better genetics tend to be able to “do more with less” in my observation. So often my early intermediate program is some flavor of Heavy-Light-Medium programming that allows me to jack up volume and frequency without burning my client out, but in this instance with Jackson, he just wasn’t responding well to this type of programming. We played around with myriad variations of set, rep, and intensity combinations, but his “slow and steady” progression, was a little too slow and steady for my taste, so we tried a different approach. I cut his frequency way back. Once per week for the Bench. Once per week for the Press. I jacked up his per session volume. I varied his exercise selection up, a lot. So basically I gave him a routine that was straight out of my KSC Method for Power-Building Program. Monday we Bench Press. We run in 3 week cycles, between sets of 8 in week 1, sets of 5 in week 2, and sets of 2 in week 3. We do 3 work sets. On the last set each week, I have him squeeze out any extra reps if they are available. I have been using my 852 Program for many years with my clients and it rarely lets me down, although it’s usually not my immediate “go to” for an underweight, early intermediate. But in this case it worked well. After the Bench Press we go into Incline Pressing. On the 8s week, we do Dumbbell Incline Presses for sets of 8-12 reps. 3 work sets after warm up. On the 5s and 2s week we do Barbell Incline Presses for 3 work sets. On the 5s week, we do 3 sets of 6-8 reps. On the 2s week we do 3 descending sets. Set 1 is for 3-5 reps, Set 2 is for 5-7 reps, Set 3 is for 8-12 reps. After the Bench & Incline Presses, we give the Chest and Triceps a brief rest while we knock out 3 sets of heavy barbell or dumbbell curls. We alternate weekly which we start with, usually 3 sets of 6-8 reps. Then we finish the workout with a super set of Weighted Dips in the 10-15 rep range (he’s really good at Dips) and either barbell or dumbbell curls for sets of 10-12 reps (the inverse of whichever we started with). Bench Press 3 x 8 / 3 x 5 / 3 x 2 (alternate weekly) DB or BB Incline Press 3 x 8-12 / 3 x 6-8 / 3 x 3-5, 5-7, 8-12 Heavy Barbell or Dumbbell Curls 3 x 6-8 Weighted Dips 3 x 10-15 Barbell or Dumbbell Curls 3 x 10-12 (superset with Dips) On Thursday we Press. Same protocol as the Bench Press (sets of 8, 5, or 2). We follow the Press with 3 work sets of Close Grip Bench Press in the 8-10 range. After the Close Grips we move into Seated Dumbbell Presses for 3 work sets in the 8-12 range. We’ve played with Seated Dumbbell Presses performed before the Close Grips (how I’d normally program this) but for him we get more out of both lifts with this sequence. I don’t ask too many questions – I just observe and follow trends. After the DB work we move into an isolation tricep exercise. Most of the time this is a Lying Tricep Extension with an EZ Curl Bar. If he has a week where he stalls then I switch the exercise out for 2-3 weeks with a Cable Tricep Pressdown or an Overhead Extension with a single dumbbell. Then we get back to the LTE as I find this is probably the most effective all around isolation tricep movement. If we have time, we finish with 3 sets of Bodyweight Dips to failure. Being light, the kid can Dip all day. I’d say we do these 50% of the time and the other 50% we skip them due to time limitations or because he’s just simply smoked. Press 3 x 8 / 3 x 5 / 3 x 2 Close Grip Bench 3 x 8-10 Seated DB Press 3 x 8-12 Lying Tricep Extension 3 x 8-12 Bodyweight Dips 3 x max (optional) Following this protocol his Bench and Press have exploded and continue to explode week to week, and so has his physique. Noticeably bigger chest, shoulders, and arms. If you are interested in learning more about this style of programming, I’d encourage you to pick up a copy of my KSC Method for Power Building. Inside I lay out the details of 852 programming, setting up a Power Building style training split, and organizing an assistance exercise template. Again, I’m not saying this programming example will work for you. It might not be right for you. But it might. Don’t get wrapped up in the details and minutia but instead see the broader point of the case study which is to try something new if what you are doing is not working. I’m not a fan of program hopping every few weeks. But if you are giving a certain style of training a good honest effort for 8-12 weeks or so and progress is minimal or non-existent…….change. Training OCD – channel it the RIGHT way In the spirit of not being OCD I’m gonna try and keep this article about being OCD short and to the point. This topic can easily get me off on a rambling tangent so maybe that’s ADD and not OCD….whatever. The bottom line is this: a lot of the clients I’m working with and a lot of the trainees I’m talking to suffer from some degree of OCD about their training. And in many cases it is absolutely killing their progress. Killing their progress because they focus and obsess around the things that really don’t matter that much over time. There is nothing wrong with analyzing and tracking the details of your training and programming – in fact you should be tracking key numbers – but you need to focus those OCD tendencies in the right places in order to get the results you want. First you need to recognize a few things – there is no magical combination of volume, intensity, frequency, and exercise selection that is going to unlock the magical vault of gains. There is obviously a ballpark that you need to fall into, but the exact numbers are all a moving target week to week and month to month as our physical status changes. To simplify, we are basically in a continuous state of building up adaptations and resistance to the various stimulus in our program while at the same time compiling varying levels of fatigue while forming those adaptations. So our state of “fitness” and our state of “fatigue” are basically constantly moving up and down and this is not something that can easily be measured. Add to this the constant variable of outside the gym stresses such as sleep, nutrition, stress, or just the daily ebbs and flows of our body, and this makes finding what is “optimal” very difficult indeed. The PR (personal record) set is the best measurement we have to figure out whether our training is in that ball park of optimality or not. If you never test anything – how do you know things are working? Now, with all things the devil is in the details. For guys that have been training more than a few years (consistently) you can’t go into the gym every week and try and PR your squat, bench, deadlift whether it be a 1-rep max or a 5-rep max or whatever “test” you assign value to. But this is where variety in exercise selection comes in. The longer I program for clients the more I have come to believe in the utility of supplemental and assistance exercises for the intermediate and advanced lifter. You need to get stronger and better at a wider variety of exercises in the gym in order to drive progress on the main lifts that you may care about. This is even more true if your goals are mainly physique oriented and less power lifting oriented. Power lifters require some specificity in their training, but bodybuilders don’t (in terms of exercises you must retain in your program). This doesn’t mean that you stop training the big lifts – especially as a power lifter – you have to train the big 3. It simply means that you can’t just use the big lifts as the main driver of progress for eternity. It works exceedingly well as a novice. It works pretty well as an early intermediate, and then those “magical” combinations of sets/reps/intensity/frequencies get harder and harder to nail with precision over time. When simple reorganization of sets, reps, and frequency starts to dry up lifters start to fall into the abyss of OCD trying to figure out that set-rep-frequency combo that will get them moving again. I think that magical combination probably exist for most lifters. It’s just really hard to pin point. This can lead to months of lost training time as lifters punch the clock repeating the same exercises over and over again with layers and layers of submaximal sets perhaps leading to some minimal strength gains, and very little change in physique. I think the better way to channel your focus is on a new set of exercises that support and build the main lifts. And then get OCD about setting constant PRs on these exercises. With a wider variety of exercises you can train with a higher level of intensity (i.e. intensiveness / effort) day in and day out. When a lift fails to make progress after several weeks – drop it. Replace it with something else and come back to it in a few weeks. This type of mentality has been a hallmark of successful programs such as the Westside Method of training. Max Effort Lifts, supplemental lifts, and assistance exercises are rotated in and out of the program CONSTANTLY. The more advanced you are the more often you rotate your exercises. The main lifts are trained weekly or nearly weekly, but not maximally. You stay in the groove by accumulating lots of volume via speed work which is effective, but doesn’t wipe your system out. Over the last several years, I’ve converted the power building track of my online coaching program over to a strictly conjugate style of training and the results have been fantastic. With many of my lifters I have to get on their ass all the time about keeping focus and keeping track of PR SETS when they hit their assistance and max effort exercises. This system doesn’t work if you are a clock puncher. You cannot just Ho-Hum go knock out 3 x 10 nowhere near failure on a lying tricep extension and expect it to make your arms grow or carry over to the big lifts. You have to PR that mother fucker as often as you can and you need to be taking the smaller exercises to failure or even beyond. And then when progress stalls for a workout or two you switch over to a French press or dips or cable pressdowns or whatever else you want to use, and still focus on building up PRs on that new exercise as often as possible. Track your PRs on every exercise at every rep range. Add weight, add reps, something. Don’t get caught up in obsessing about total volume and all that shit. In terms of HYPERTROPHY I have seen some of the best progress from myself and from my clients when going down to about 2 sets of each exercise. One big heavy set in like the 4-8 rep range focused on maximal loading, followed by an all-out set in the 10-20 range. In both rep ranges, we’re constantly chasing more weight or more reps. This type of training was a hallmark of Dante Trudel in the 90s and 2000s who produced some insanely good bodybuilders with his DoggCrapp system of training. Dante changed the paradigm by getting bodybuilders away from thinking about just piling up set after set after set and instead got them OCD level focused on “beating their log books” on a very low training volume, chasing PRs over just 1-2 all out work sets. And just like Westside, Dante was a big believer in keeping up with a rotation of exercises for a period of time, and then intermittently dropping and replacing an exercise when it failed to produce a PR. He’d wait a few weeks or months and return to that exercise for new PRs. Borge Fagerli’s system of Myo-Rep sets are extremely effective, but not new. Borge’s system can trace its origins back to Dante and his DC training. Dante’s rest-pause sets and Borge’s myo-rep sets are basically slight variations of each other but both feature a focus on setting small PRs on either weight or reps using effort and effective reps rather than total volume to drive adaptation. Even with the added rest-pause sets or myo-reps or whatever you want to call it, the total volume still winds up being relatively low, but there are multiple points of failure in every set and the reps you wind up doing wind up being more effective than compiling a bunch of submaximal work. The argument I’m making here is not for low or high volume necessarily, nor am I arguing that everyone needs to start using DC training or myo-reps. It’s about effort, intensiveness, and obsessively “log booking” every exercise you do. Not just your squat, bench, and deadlift. Your RDLs, your Dips, your Rows – whatever exercise you do – do it with the express purpose of trying to beat a previous performance on that exercise – however small that increment might be. The additional rep you squeeze out or the additional 5 lbs you add to the bar all add up over time. So instead of worrying so much about whether you should do 3×8 or 5×5 or 4×10, or WHATEVER……worry about whether you are PRing your lifts regularly. If your excessive training volume is preventing you from doing so – drop your training volume. Most of the programming I run is pretty middle of the road in terms of volume and frequency, whether it’s for strength or hypertrophy purposes. It’s just weird talking to some lifters because they get super focused on things like what brand of shoes they should squat with? Ohio bar vs Texas bar? 4×5 or 5×4? Does their gym have calibrated plates? And don’t even get me started with the form stuff. Guys deloading by 10% because their big toe wiggled on the fifth set of squats yesterday. That kind of thing. But then when it comes to THE ACTUAL TRAINING they seem to be unconcerned with the details that matter – like more weight or more reps on some sort of consistent basis. 500 lb Deadlift PR for Frank! (age 67) Patience, Persistence, and Tenacity. That's what it took for Frank to finally achieve his goal of a 500 lb Deadlift. No special tricks. No secrets. No end runs around effort. Frank has been a long time client of mine, and we have worked together for many years. And for the last several years we have had a sticking point on the Deadlift of around 475480. That's awfully damn close to 500, and too close to that magic number to simply stop at 475. But no matter what adjustments we made to the programming we kept ending up around the same ol' 475-480. That's actually not too shabby for a guy that is 67 years old and below 200 lbs of body weight. But we stayed the course, kept adjusting, kept pushing, until we finally introduced the variable that brought us that last 20-25 lbs of progress.... SPEED!!!!!! For the last several months we have trained exclusively with sets of 2-3 reps on the Squat and Deadlift. All weights were sub-maximal for that rep range, but every set was pulled with maximal volitional speed. Frank started slow, but he got faster. And faster. His ability to generate force and generate force quickly improved. We cruised from a 1RM of 475 to 500 without missing a single rep in training. We only Deadlift once per week. 4 to 6 total sets. One set is heavy for 1 to 3 reps. Then we deload the barbell and pull the rest of our sets with maximal volitional speed for sets of 23. I'd estimate our average intensity is around 75-80% of 1RM. Based on the speed of his 500 lb single, I don't actually think 500 is a 1-rep max. Our last training day was 5 sets of 2 reps @ 415. I'd estimate that to be about 80% of his actual 1-rep max. If you have a lift that is stuck, consider other variables beyond just more intensity or more volume. Improving the quality of your repetitions via increased average bar speed can be incredibly effective. How To Do a Rest-Pause Set Rest-Pause Sets have been around for a long time but they really took off in popularity in the late 90s and early 2000s. Their quick rise in popularity was due, in total, to the work of bodybuilder and bodybuilding coach Dante Trudel. Dante is the man behind the infamous "DoggCrapp" or "DC" training program. DC training is one of the few programs in the bodybuilding world that very strong and very big lifters actually used and wasn't some ghost written muscle mag garbage. One of the main components of the DC Training Program were the Rest-Pause sets. For those of you familiar with "Myo-Reps"......Rest-Pause was the precursor. As I always say, there is very little that is new. It's all recycled and renamed and slightly tweaked and updated. Rest-Pause sets are fairly simple to perform, but brutally hard, and wildly effective. The first set is your activation set. The rep range can vary based on the exercise and the lifter, but in general the lifter is going to aim to hit failure somewhere between 8 and 20 reps. This will be followed by a short rest. You can time the rest with a stop watch and aim for about 30 seconds. Or just take 10-15 big deep breaths between sets. That often comes out to between 20-30 seconds. (I prefer the stop watch because it keeps me consistent). Once your rest period is over you go right into the second set. You won't be recovered. But you try to get to around 50% of the reps of the first set. It might be less or more based on the fatigue created by the first set, but you push as hard as you can on that set for as many reps as you can get. Then take another 20-30 second rest. Then get another max effort set. Again, aiming for about 50% of the reps you got on the second set. As an example.....lets say you do a Barbell Curl with 95 lbs for 16 reps on the first set. Rest 30 seconds and aim for 8 reps. Rest 30 seconds and aim for 4 reps. Keep form strict and maintain full range of motion. Don't sacrifice form for pursuit of more reps. If you do it right, you aren't going to need more than one Rest-Pause set for any one exercise. And you probably won't do more than 1 or 2 rest-pause sets for any one muscle group. This only works if you are pushing very very hard. Every set to technical failure. Another tool for the tool kit! 50% Sets....Build Size & Save Time One of the first thing my clients notice about working with me is that I have a lot of tools in my tool box. I'll use just about anything and I'm not married to any single approach to training. I don't say that in order to brag on my own ingenuity and brilliance, but rather to highlight the fact that I'm not afraid to beg, steal, and borrow methods from just about anyone that has a great idea when it comes to training more effectively and more efficiently!!! One method I've really come to like is the concept of "50% sets" made popular by the late great Dr. Ken Leistner. Dr. Ken was way ahead of his time in recognizing the concept of "effective reps". In other words, it's not just about the total number of reps you do in a workout, but how many of those reps are truly stimulative towards more growth. A 50% Set basically goes like this..... Perform a maximum effort set in the 10-20 rep range. You don't have to hit absolute failure, but you need to come pretty damn close. Then rest exactly 60 seconds. Then start the next set with a goal of 50% of the first set. So if you hit 12 reps on the first set, aim for 6 reps on the second set. If you hit 50%, go up in weight next time. If you don't, stay with the same weight for the same number of reps on the first set. Then the next time you hit this workout you try to increase the reps of set #2. If you want, you can add a third 50% set by resting another 30-60 seconds and trying to get 50% of the 2nd set. In this case you might hit a Barbell Curls with 100 lbs for 12 reps...rest 60 seconds and hit 6......rest 30-60 seconds and hit 3 reps. Then you're done. It's brutal and it's time efficient. It's also almost identical to Dante Trudel's DC Rest-Pause sets. DC training has a long track record of success at all levels of bodybuilding. Neither coach was / is a huge fan of total volume for hypertrophy. Both systems focus on short bursts of extremely focused, extremely intense efforts with a focus on progressive overload over time. No junk volume, every rep counts. If you're tired of the standard old 3 x 10 for hypertrophy, and you want better results in less time, try out some of Dr. Ken's 50% sets. I've been using them with my clients. They work, they're fun, and very time efficient. Top Set + Back Off Set (Simple Low Volume Approach to Hypertrophy) You might be doing a lot more work than you need to do to grow. Or you might be doing just enough. Or you might might not be doing enough. Wow, I know I'm really going out on a limb here with those 3 statements. But that's the reality folks. There are a lot of different approaches that can work for different lifters based on their goals and experience. There is no one best approach that uniformly applies to all of us. The current trend right now is all about training volume for hypertrophy. The more you do, the more you grow!! Not necessarily. I have a lot of clients that simply don't respond well to a lot of training volume. And I have clients that respond well to a TON of training volume. Most of my clients do best on a middle of the road approach with slight shifts in either direction based on a given response week to week or month to month. When a lift gets stuck - we nudge up the volume. When we start feeling burnt out - we back things down. It's a safe and effective approach that avoids wild swings in either direction of super high volumes or ultra low volumes. Don't Detrain. Don't Overtrain. Stay middle of the road and nudge each lift in either direction on a lift by lift basis. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------But if you are a low volume type of guy, you might really like what a lot of us at the gym are doing right now, including myself. I'm basically just doing 2 work sets per exercise. That's it. My goal is to get the most effect out of the least amount of work. We're doing one top set of an exercise, plus one back off set. 1-2 exercises per muscle group at a each training session. We're training 4-5 times per week in an upper / lower split. We have 3 rep ranges that we work within: 5-10, 10-15, and 15-20. You pick 2 rep ranges for each exercise - 1 for the top set and 1 for the back off set. Each upper and lower session has 6 exercises. Upper body sessions are generally structured like this: Bench Press 1 x 5-10, 1 x 10-15 Barbell Row 1 x 5-10, 1 x 15-20 (or 1 x 10-15, 1 x 15-20) Strict Press 1 x 5-10, 1 x 10-15 V-Grip Pulldowns - 50% set Tricep Extension - 50% set Bicep Curl - 50% set For many of the smaller exercises we opt to use 50% sets which I detailed out in my last email. For 50% sets we just hit a single max effort set between 10-20 reps, rest 60 seconds and aim to hit 50% of the reps of the first set. Then rest another 30-60 seconds and aim to hit 50% of the reps from the second set. Lower Body Sessions might look like this: Squat 1 x 5-10, 1 x 10-15 or 15-20 RDL 1 x 5-10, 1 x 10-15 Leg Extension - 50% sets Leg Curls - 50% sets Calf Raise - 50% sets Abs - 2 x 15-20 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------BUT THAT ISN'T ENOUGH VOLUME!!!!!!!!!!!!!! Yep. In many instances it won't be. Not everybody responds well to low volume and some are going to need a lot more to grow. Or....you are like a lot of my clients and you THINK you need a lot more volume to grow. I guess my question would be.....how long have you been doing what you are doing and is it working? Are you putting in 90 minute or 2 hour workouts and not growing??? I know many of you are. If so, maybe try an alternative approach ___________________________________________________________________________ A few tips to make this approach work.... 1. You have to take every set as close to failure as possible. Leaving 3-4 reps in reserve each set does not work for low volume approaches 2. You have to use a log book and constantly try and set new records for weight or for reps within each rep range. If you just "go by feel" it probably won't work. Having that numerical goal for every set will help you push deeper into each set. 3. Don't do the same exercises every workout. You'll burn out HARD by trying to push this deep into failure on the same exercise multiple times per week. Set up 3 different workouts with different exercises that you rotate through each session. Example: Week 1: Monday - Upper Body A Week 1: Thursday: Upper Body B Week 2: Monday: Upper Body C Week 2: Thursday: Upper Body A Week 3: Monday: Upper Body B Week 3: Thursday: Upper Body C Referencing the example upper body workout from above....we'll call that session A.....session B might be structured like this: Incline Press 5-10, .10-15 Pulldowns 5-10, 10-15 Seated DB Press 5-10, 10-15 Cable Rows 10-15, 15-20 Dips 10-15, 15-20 Shrugs 50% set You focus 100% on getting stronger within each rep range for each exercise and you'll see some growth. If you are like me you will SUCK at all the stuff between 10-20 reps, but as I've gotten better at work in that rep range, I've seen the best results. It's 1 rep at a time and 5 lbs at a time. Stacked up over weeks and months it all starts to add up. Power Rack Power Rack Series - Part 1: Rack Pulls Over the course of the next several weeks and/or months we will be taking an in depth look at how all of us can better utilize one of the most important pieces of equipment for the strength athlete – the power rack. The series will be at least four parts, each part dedicated to assistance exercises for the Deadlift, Squat, Bench Press, and Press. Most of the exercises that will be discussed in this piece are referenced in Rippetoe’s Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training, so we will not overly focus on how to perform each lift. If you are unfamiliar with how to do these exercises then make the investment in SS: BBT. Instead we will examine how and when to program these very important exercises for optimal results and most importantly carryover to their parent exercises. Part I will start with probably the most common exercise performed in the power rack: the Rack Pull. Rack Pulls are essentially partial ROM deadlifts pulled from some point just below the knee (or on the top half of the shin), right at the knee, or just above the knee. There is not necessarily one position in which the lifter should always do his rack pulls. In fact an argument could be made that variation in the height of the pull is a good thing to strengthen all areas of the back. Middle to Top of Shin This is the longest ROM pin position which will generally have the plates only a few inches off the ground. This is just enough height to eliminate the quads from the “breaking” of the bar from its dead stop position. From this height, the lifter can feel a stretch in the hamstrings while setting up. The more he feels this stretch in the set up, the more they will be involved in the pull on the way up. This height rack pull involves the most amount of muscle mass. At Knee or Just Below Knee Many lifters will find that this is a very difficult height to pull from. From this position the ROM has been shortened enough so that there is significantly less hamstring involvement. This means that the lifter is using a whole lot of glute and low back to break the weight from the pins. I personally find that my weakest Rack Pull position is directly even with my knee cap. I can just find no tightness whatsoever in the set up. Arguably this is a good thing from a training standpoint. Above Knee This is probably the most abused Rack Pull position in the gym. The very short range of motion allows for very very heavy weights to be pulled, but the incredibly short range of motion may or may not have a lot of carryover to a full deadlift. What is the right height for you? As with many things, the answer is “it depends.” The subjective difficulty of the Rack Pull is greatly influenced by a lifter’s height and his build. I would encourage all lifters interested in the lift to experiment with various heights and find their weak and strong points throughout the range of motion. Typically lifters will do better to focus their training on the areas in the lift where they feel the weakest. Again, for me, that position is directly at the knee cap. I can actually Rack Pull more weight if I move the bar down a few inches and get more hamstring involvement. This tells me I probably have some weakness in my erectors that is ultimately holding back my regular deadlifts. For you it may be different. Sets & Reps Like Deadlifts, Rack Pulls can be useful along the repetition continuum from heavy singles to sets of 10. Whatever the rep range used, 1-2 sets is probably plenty of work for a lifter strong enough to even be bothering with the exercise. That is one main workset with perhaps one back off set for extra volume. If you want to pull heavy singles on the Rack Pull I recommend using one of the lower pin positions (from below knee to midshin). Use the singles to strengthen as much of the ROM as possible without the use of the quads. When pulling at knee height or above knee height I prefer to use sets of 4-12. If you are particularly strong above the knee it may be tempting to really pile on the plates and impress the whole gym with how much you can rack pull 4 inches. On occasion it may not be a bad idea to let your CNS feel what this much weight feels like, but it is just unlikely that very short range of motion lifts will carry over to the full range of motion deadlift. And again, we are using Rack Pulls to strengthen the deadlift, not just for the sake of Rack Pulling. Short ROM Rack Pulls are better thought of as a way to strengthen the erectors rather than test your absolute strength. This means using rep work to build muscle mass. An excellent way to do this is to work up to around a 4-6 rep max on the first main work set and then perform a back off set with around 8-12 reps. After doing so your back should be experiencing a massive pump from the base of your spinal erectors to the top of your traps. When/Why do Rack Pulls? Rack Pulls are most often a replacement exercise for the deadlift. As lifters get into the mid400 range for rep work it often becomes very difficult to deadlift week in and week out and make progress. Rack Pulls are an excellent alternative to alternate back and forth with regular deadlifts. They still allow you to use very heavy weights but the fluctuation in load and range of motion can keep the lifter from getting stuck in his deadlift training. Rack Pulls can also be done as back off work after regular deadlifts. For instance, the lifter might work up to a heavy single or double with his regular deadlift and then go to the rack and pull a heavy set of 4-6 for extra stress on his erectors. This is the appropriate way to use deadlifts and Rack Pulls in the same training week. Deadlifts on one day of the week and Rack Pulls on another would completely burn out most lifters, and progress on both lifts would come to a halt very quickly. Basic Programming Rack Pulls work very well as part of a rotation of heavy pulling exercises, and they would be installed on whatever your heavy pulling day is each week. A good strategy to use when setting up a deadlifting rotation is to do one week where “bottom end” strength is emphasized and one week where “top end’ strength is emphasized. This could be as little as two exercises. A popular set up is often used by Mark Rippetoe using just a simple weekly rotation of Rack Pulls and Halting Deadlifts. For even more variety, below is an example of a 6 exercise rotation using three different types of Rack Pulls: Week 1: Deadlift Week 2: Rack Pull (top of shin) Week 3: Deficit Deadlift Week 4: Rack Pull (knee height) Week 5: Stiff Leg Deadlifts Week 6: Rack Pull (above knee) This routine is not a prescription, but just an example of how one might think about setting up their training incorporating the Rack Pull. Power Rack Series - Part 2: Dead-Stop Rack Bench Press Using the power rack pins for the bench press and standing press is a powerful yet underutilized tool in my opinion. Like the rack pull, rack presses and bench presses can be employed in a variety of ways to improve various aspects of each lift. Typically, when rack presses are described they are associated with lockouts. But this is only one way to employ this powerful exercise, and arguably the least effective. For the bench press, “lockout” work is by far the most popular variation of the exercise. This is in large part because the exercise has been widely written about by geared lifters and those who coach geared lifters, and for them, the top end of the movement is of course very important. It’s also popular because it enables lifters to use tremendous amounts of weight. And this is always fun and good for the ego. But for those of us who prefer to lift raw (think t-shirt and a belt) we need our focus to be on the bottom end of the lift. Enter the Deadstop Rack Bench Press The Deadstop Rack Bench Press has been around for many decades but, mysteriously, is still not something you see in wide use today. This particular variation of the movement calls for the lifter to start with the bar resting on the pins at the lowest point possible without actually resting on the chest. From here the lifter has to actually crawl or slide between the bar and the bench and get set up. After tightening up, the lifter must explode into the bar with zero momentum and zero stretch reflex. This is a serious challenge and your Deadstop Rack Bench Press 1RM will be significantly less than your Bench Press 1RM. In fact, it will be significantly less than if you had actively lowered the barbell to the pins and paused. Even if a long pause is used of 3-5 seconds, it still is not the same challenge as the “dead stop” version of the lift. The exercise can also be done with a medium or close grip. This makes the movement even harder and places more stress on the triceps to finish the lift. Make no mistake, even though lockout work gets the credit as the best tricep builder, dead stops are not solely for bottom end strength. One thing you will notice if you do the lift is how amazingly slow the lift starts out at the bottom. There is very little speed with a heavy weight, so when the bar gets to the midpoint of the lift where the triceps take over, the bar is moving very slowly and carrying very little momentum. So when the triceps kick in they have to really kick in or the lift will stall halfway up. I have lost several at the halfway point. The other advantage to a close or medium grip is safety. Wider grips place more stress on the pecs which is the area most exposed to injury with this lift. Deadstop Rack Bench Presses are best trained for singles only. Working up to a 1RM in the lift is fine, but it is also risky from an injury perspective. Pec injuries (especially around the very sensitive pec/delt tie in area) are common if the exercised is used too often with too much weight. Therefore, a more effective method may be to use multiple singles for sets across. For high intensity work 3-6 heavy singles with complete rest periods is appropriate. For higher volume work 10-15 high speed singles with 30-60 sec rest can also be effective. Whether you go heavy or fast, nothing quite builds explosion from the bottom end like dead stop bench presses. Below is sample way to program the Dead Stop Rack Bench Press Texas Method Volume Day – Bench Press 5×5 Intensity Day – Bench Press 5×1 (week 1) Dead Stop Rack Bench Press 5×1 (week 2) This method alternates the exercise in with regular bench presses every other week. In my opinion this exercise is best used as part of a rotational concept instead of something that is done week in and week out. It’s simply just too stressful on the shoulders/pecs to be used every week. Power Rack Series - Part 3: Standing Rack Press In Part II of the series we examined the benefits of the Dead-stop Rack Bench Press for building explosive power at the bottom of the Bench Press. In Part III we will take a look at an extremely effective variant for the Standing Press. Standing Rack Presses can be done from multiple locations within the range of motion of a standard press. My favorite starting position is about 1-3 inches just above the shoulders. This will generally lie somewhere between the collar bone and the chin. At this point in the movement, the range of motion is still fairly long, but the leverage is quite poor. The lifter is starting the lift with very little tension built up in the front deltoids and upper chest. In the starting position of a standard press, when the bar is resting on the clavicle, the lifter has the benefit of having that tension in the upper chest and front delts, so that when he starts the lift he is getting a little bit of a boost from the bottom. It is not uncommon, therefore, to see a lifter fail a heavy press an inch or so off his shoulders. Ideally, in this variant of the Rack Press, the lifter would be initiating the lift from the lowest point in which he might fail. Or thought of another way, the point in which the upper chest and front deltoids release their tension. When done correctly, a Rack Press done from this height will start VERY slowly. It will be a slow grind off the pins, and for a brief moment it may feel like the weight isn’t going to budge at all. From here it will be a slow grind all the way to lockout as the lifter is never able to generate any momentum on the bar. Simply put, this variant is HARD. You should expect to be lifting significantly less poundage than you would be with a standard press – even though the ROM is shorter. You’ll quickly learn that the upper chest/front delt tension accounts for a lot. Just to give you a frame of reference, my 1RM Press is 285 lbs, and my 1RM Rack Press from just below my chin is 245 lbs. The next Rack Press height should generally fall somewhere right in the middle of the ROM. For most this will be somewhere between upper lip and eyebrow. This will be at the point where upper chest and delts start to transfer a significant load onto the triceps. For this reason, this is another point where lifters commonly fail on heavy presses. It’s not a bad idea to get some video of yourself doing some heavy press attempts and try and figure out where exactly you tend to miss. It’s not always the same for everyone. Lastly, Rack Lockouts are also an effective exercise. Lockouts for raw lifters tend to be more effective for Presses than for Bench Presses. The range of motion is longer (especially for a tall long armed lifter) and more stress is placed on the triceps during Presses than Bench Presses. It is much more common to see lifters failing to lock out Presses than it is Bench Presses. Starting around the forehead or hairline is a good estimate for most. Anything higher than that is generally not as productive. A training tip for all three variants: Stay strict and minimize layback. When doing Rack Presses we are trying to work specific areas of weakness in the ROM. Make sure stress is directed to the appropriate areas and you aren’t just “sneaking” under the bar with excessive layback. That defeats the purpose of the exercise. Programming If your program has you doing two days of Pressing each week, then it is a good idea to continue to regular Presses for volume one day of the week, and Rack Press for singles across or 1RMs later in the week. Rack Presses are best trained for singles. If you do decide to do rep work with Rack Presses, just make sure to deweight each rep on the pins for 2-3 seconds for full effect. If your program has you only Pressing once per week, then you should Press for volume one week, and on alternate weeks do a high volume of Rack Presses for singles across. Anywhere from 5-10 singles across is appropriate. As for which variant to use, it tends to be an individual thing. Almost everyone will benefit from the first variation I listed – starting just 1-3 inches off the chest. The inclusion of mid-range Rack Presses and Rack Lockouts will be individual to each lifter – their use will only be included if you tend to miss reps at that level. And it is possible that this can change over time. Power Rack Series - Part 4: Rack Squats vs Box Squats Traditionally there are two types of Rack Squats, both of which are underused in my opinion. The first variation of the Rack Squat involves lowering the bar down to the pins inside of a power cage and pausing for just a few seconds then exploding back up with the weight. The second variation is the harder variation (and utilized even less) and involves starting the lift with the bar resting on the pins. Both have value under the right circumstance. The first variation of the lift we shall just call the Rack Squat. By and large this exercise has been driven out of mainstream use due to the popularity of the box squat which accomplishes a very similar purpose. Both the pins and the box can be set to a predetermined height so that the trainee has a quantitative indicator of where he/she should pause with the weight. Any sort of paused squat variation can be useful in developing power out of the hole on a traditional squat that utilizes a hard stretch reflex. Take the stretch reflex away, the lift gets harder, and hopefully you get stronger. It generally does work. HOWEVER, it has been my experience in my own training and in the training of my clients that box squats do not always have carryover for the raw lifter. It isn’t that box squats don’t work to get the lifter stronger, they do, but they can also create a dependence on the surface area of the box at the bottom of the squat. Lifters who train too often with a box can start to lose the subjective feel for what the bottom of the squat should feel like. So even though they may have gotten stronger by training the box squat, we often see this cancelled out by the loss of proprioceptive “feel” for the bottom end of the regular back squat. What you will find is that lifters get tentative and hesitant at the bottom of the squat when the box is taken away. Is this universal? No. I know several raw lifters who do lots and lots of work off a box with no negative consequences. But there are enough problems created by box squats for a raw lifter that an alternative method is useful to have in your hip pocket. Enter the Rack Squat. The Rack Squat gives a marker for depth just as the box does, but since the pins come into contact with the bar and not the butt, the lifter doesn’t seem to develop the same dependence for finding the bottom of the squat. In my opinion, for paused squat work of this nature, the Rack Squat is superior to the Box Squat for the raw lifter. A couple of interesting comparative notes. At the same level of depth and for the same length of the pause, the Rack Squat will utilize less weight than the Box Squat. This is almost universal, and may be further evidence that it is the more useful exercise. As I allude to in Practical Programming 3rd Ed I tend to favor exercise variants that “underload” movements rather than “overload” them. Part of the reason for the weight differential is because the box allows the lifter to rock back (even if it is very subtle) and gather momentum for the ascension. The Rack Squat holds the bottom position of the squat completely immobile. There is no ability to rock back or forwards, and momentum is absent from the lift. Lifters will also find a difference in where they get sore from each lift. Rack Squats traditionally create much more quad soreness than Box Squats, which tend to create more soreness in the glutes and hamstrings. Again, much of this has to do with how much the box allows the lifter to sit back into the squat, often getting the bar behind the middle of the foot. In a box squat this is acceptable because the box is there to “catch” you, and it allows you to rock forward to get the bar back over the middle of the foot where it can be lifted. The Rack Squat tends to follow the mechanics of a regular back squat a little closer. Programming Rack Squats can be used for singles for up to sets of 5. Rack Squats are a pure strength and power exercise and getting out of this range is getting out of the strength and power range. Below are several ways in which Rack Squats could be programmed into some traditional training splits: Back Off Sets: After your main work set or sets of Squats do 1-2 back off sets of Rack Squats with lighter weight. So a trainee who squatted 500×3 for his main work set, might strip the bar down to 405 and do 2×5 for added volume. Substitute: If a trainee does 5×5 sets of squats once per week as part of his heavy training day, he might alternate every other week with 5×5 sets of rack squats. Medium Day: If using a Heavy Light Medium routine, Rack Squats make an excellent medium day exercise. Just be careful with total volume because they are very stressful. In fact, they are too stressful to every be considered a light day exercise Dynamic Effort Sets: Most of those who use Dynamic Effort method sets utilize a box. Next time you do your Dynamic Effort Squat workout, try doing Rack Squats instead of box squats for 8-12 doubles on the clock. You can still use bands and chains with Rack Squats Max Effort Work: If you have a rotation of max effort squat/deadlift exercises, plug these into the rotation. Rack Squats work great for heavy singles. Last Tip: Use a coach, training partner, or cell phone camera to find the right height for the pins of the power cage. The temptation with the Rack Squat is to go high and use a lot of weight. Take the pins low enough so that you can sink down to just below parallel. The crease of your hip joint should be just below the top of your knee. Do NOT bounce the bar off the pins. We want to pause at the bottom for about 2-3 full seconds. The bar should be motionless before you come back up. It’s supposed to be hard! In the next week or two I will write Part 4.5 of the series and we will examine the second variation of the exercise: The Dead Stop Rack Squat Power Rack Series - Part 5: Dead Stop Rack Squats Quite possibly the single most difficult exercise you can do in the gym is the Dead Stop Rack Squat. We talk about “grinding” reps out all the time, but nothing embodies the “grinding” rep more so than a Dead Stop Rack Squat. The difficulty of the exercise has the potential to make you incredibly strong, but it must be respected as well. It is not an exercise for a beginner, and there are some inherent risks involved with the exercise, that even intermediate and advanced lifters should be aware of. First, let’s define the exercise. The Dead Stop Rack Squat begins with the bar resting on the pins of the power cage. The height of the pins will vary from lifter to lifter. The bar should be set at a height that allows the lifter to start from a position with the crease of the hip joint just below the top of the knee. In other words, just below parallel or right at parallel. No higher, no lower. Once the bar is set up, the lifter begins each repetition by starting at the bottom of the squat. There is no stretch reflex, and the lifter does not actively lower the bar to the pins to start the repetition. Because of this, you can expect to be using weights much lower than your regular squat or even the regular rack squat that we addressed in the last article. Once the lifter is set up under the bar, he/she must explode into the bar to break it off the pins. Expect the first few seconds of the lift to be the hardest. It is not uncommon for the weight to feel like it isn’t going to budge. STAY WITH IT! The purpose of the exercise is to learn to get the bar moving from the dead stop. You will have to learn how to strain. Once you get the bar up the first few inches the rest of the lift gets easier…but not easy. The weight will generally move slowly for the entire range of motion. Without the rebound out of the hole, you will develop very little momentum, and it is hard to get any speed on the bar at any point. When the lift is done, return it to the pins. Because the focus of the exercise is to lift the barbell from a dead stop, the lift is best trained for singles only. Important Considerations The Dead Stop Rack Squat has tremendous carryover to both the squat and the deadlift. Training the squat with zero stretch reflex will obviously make squatting with a stretch reflex much easier. However, breaking the bar off the pins from a dead stop mimics very closely what happens when we break a deadlift off the floor. So for a lifter who is struggling with his/her deadlifts, this is an excellent assistance lift to build a more powerful break from the floor. Mechanically there are also a few other similarities to the deadlift. First, the Dead Stop Rack Squat generally forces the lifter to use a slightly more horizontal back angle than whatever their regular squat uses. Second, the Dead Stop Rack Squat does not employ any significant amount of hip drive to get the bar moving. Doing so will almost always throw the lifter too far forward and he won’t be able to move the bar. So the exercise is initiated much more so with the quads than a regular squat is – just like a deadlift. For these reasons, I think of Dead Stop Rack Squats to be as much an assistance movement for the deadlift as I do for the squat – maybe more so. Programming Dead Stop Rack Squats will be used on whatever day the lifter schedules their heavy squatting/pulling. Generally the exercise will be done in place of the heavy squats or deadlifts (or both), not in addition to them. It is a very stressful exercise and must be respected. This is not an exercise that should be used on a weekly basis for any significant length of time. Every other week is probably a good idea if you want to implement them into your routine. The movement creates a lot of stress on the back and the knees, and the slow grinding nature of the lift is very hard to recover from. Below are some typical training splits. The examples show where the Dead Stop Rack Squat might fit into the plan. Only squatting and pulling movements are show for the sake of simplicity. Texas Method Volume Day – Squat 5×5, Power Clean 5×3 Recovery Day – Squat 2×5 Intensity Day – Dead Stop Rack Squat – 1RM, followed by 5 singles @ 95%. RDL – 3×5 (we would intentionally select a pulling movement that creates less stress than a heavy pull from the floor, if we are going to pull on the same day as we rack squat). Heavy-Light-Medium Heavy Day – Dead Stop Rack Squat 10 singles @ 90% in place of normal Squat 5RM. Light Day – Squat 3×5 Medium Day – Squat 4×5 Split Routine Monday – Bench Day Tuesday – Squat Day: Squat 5×5 Thursday – Press Day Friday – Deadlift Day: Replace Deadlifts with Dead Stop Rack Squats for 5 singles across If using a Westside styled template with a Dynamic Effort Squat/Deadlift day, and a Max Effort Day, Dead Stop Rack Squats make an excellent max effort exercise to work into the rotation with other squat and deadlift variations. Squat The Squat Q&A: Mechanics, Belts & Assistance (Part 1) So there are lots of questions about Squats and everything and anything related to Squats and Squat Training. Today, I decided to opt out of writing The Definitive Squat Manifesto and instead select three random points of discussion that I am often asked about. And as I’ve said before, if you get asked the same question 3-4 times you can basically multiply that by a factor of 100,000 or more to estimate the number of people that also have the same question. So, what are the 3 questions we’re going to investigate? 1. What is the ONE major mechanical error that most people make when squatting? 2. Should you wear a belt? If so, when? 3. What are the best assistance exercises for the squat? #1: The most common mechanical error…. Every week I meet with lifters who are getting serious coaching on their squat for the first time ever. Some have been squatting for many years, and some are brand new to lifting. Most have dabbled in it for a few weeks or months before realizing they don’t know what they are doing. But new or “experienced” I see a lot of the same trends week in and week out. Maybe the most common error I see is simply a lack of understanding about how bar placement on the back effects the entirety of the mechanics of the whole movement – the descent, the ascent, and the cues we use to refine the movement during the lift. I often refer to this as the “blending” of high bar squat mechanics and low bar squat mechanics – and that is something you just can’t do. As a Starting Strength Coach, I obviously prefer the low-bar back squat for all the reasons detailed in the book – more weight, more muscle mass, longest effective range of motion. And I believe that if you can squat this way you should. However, many people cannot. The most common reason people cannot low-bar squat is shoulder immobility. Especially when first starting out, people often have limitations in shoulder mobility and are forced into high bar squatting. So what I have seen people do over the years is place the bar in high-bar (on top of the traps) due to shoulder discomfort / immobility, but fail to understand that this alters the mechanics entirely from what is described in Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training. If you want to squat according to the model in Starting Strength – you can’t just change the bar position and then try and keep everything else the same. The Starting Strength Model of squatting is predicated on the barbell being in low-bar (below the traps). If you change this – you have to change nearly everything. So people come into my gym and show me their squat, and what I see is someone carrying the bar in high-bar position and trying to squat with low-bar mechanics. Not surprisingly they will often report low back pain and/or a sensation of wanting to “fall forward” with the bar or come up on their toes. When you “sit back” into a squat you must necessarily lean forward to keep yourself in balance. When you create a somewhat horizontal back angle by sitting back and leaning forward, you throw the barbell well forward of your mid-foot if the bar is on top of the traps. The mid-foot is the balance point of the entire lifter-barbell system and you cannot squat efficiently or safely with the barbell resting forward of the mid-foot. It must be over the mid-foot through the entire range of motion. This is not optional. So assuming a horizontal back angle (low bar mechanics) with the bar on top of the traps (high-bar) creates poor leverage that leads to an off balance, inefficient, and even dangerous squat. If you have to squat with the bar in high-bar position (on top of the traps) due to shoulder immobility then you have to keep a more vertical torso in order to keep the barbell centered over the mid-foot. Therefore you will think more about squatting DOWN! instead of sitting back. On the way back up, you won’t think as much about Hip Drive! as described in the book, but instead you need to focus a little more on leading up with the chest, and keeping the torso more vertical which will keep the barbell over mid-foot. So while I prefer the low-bar squat, if you are going to squat high-bar, you need to do it right. On the flip side…….. The second scenario is often a little harder to fix because it usually occurs with lifters who have been squatting a while and established some bad habits. This is where the lifter is carrying the bar in low-bar position, but is trying to squat with high bar mechanics i.e. a very vertical torso. This “blending” combination essentially places the barbell BEHIND the mid-foot during the movement and results in one of two inefficiencies. The first scenario we might see is the lifter who cannot achieve depth. Basically the lifter reaches a certain threshold of depth, beyond which, further descent into the hole would place the barbell so far behind the mid-foot that he would lose balance and possibly fall backward. Sensing this, the lifter usually has to cut his depth off about midway down. He may cite “lack of flexibility” but the real reason is that the system is off balance to the rear thus limiting his range of motion. If he would lean forward more and get the barbell centered over his mid-foot the lifter would then be in balance and full range of motion would be achievable. In the second scenario the lifter is actually able to achieve full depth BUT is experiencing a sharp change in back angle at the bottom of the squat. So the lifter descends into the hole with a chest that is too vertical thus keeping the barbell just behind mid-foot and then when he begins his ascent the barbell sharply moves forward to center itself over the midfoot. Barbells want to be over the mid-foot and given the chance they may find it for you. But when the barbell shifts forward to center itself, it forces the lifter to shift his back angle from vertical to more horizontal. At the bottom of the squat is a bad place for this to happen. We want the barbell moving in straight vertical lines up and down. We don’t want horizontal movement of the barbell during the squat and we certainly don’t want a quick forward translation of a heavy barbell when the lifter is deep in the hole. The correction for this is to get the back angle set more horizontally at the beginning of the squat and maintain virtually the same back angle throughout the range of motion. The Squat Q&A: Mechanics, Belts & Assistance (Part 2) In Part 2 of this series we’ll answer the all too commonly debated topic of lifting belts. More specifically – should you wear a lifting belt, and if so, when? The short answer to this question is – yes. You do need a lifting belt if you are going to lift seriously, but probably not on Day 1 of your novice program. But within a few weeks or a few months of your basic novice program, and certainly by the time you are training as an intermediate, you probably need to be in a belt. A belt is optional for the first few weeks, shoes are not. So if finances are an issue, hold off on the belt and invest in some decent lifting shoes first. Objections to Belt Use….. The most common objection to wearing a lifting belt is that by doing so you are neglecting to train your “core” and the belt is “doing the work of the abs for you.” The related argument is that the use of any sort of personal lifting equipment and is a slippery slope and leads to more and more gear to help maximize load on the bar. So let’s look at these arguments, which are not entirely without merit. The reality is that when squatting with a belt you will squat more weight. This is not debatable. So the belt does “artificially” aid in the squat. However, it does so through a fairly indirect mechanism. It traps pressure internally and yes, reinforces, the abdominal wall, both of which help you maintain a stronger safer more efficient posture under the bar. However, to say that it “does the work of the abs for you” is ludicrous. The abs, obliques, and low back are just as involved in the belted squat as they are in the beltless squat, and your “core” will get stronger, much stronger in fact, even in the presence of a belt. Think of a heavy beltless squat forcing your “core” to work at 100% to execute the lift. With a belt, your “core” is still at 100%….with an additional 10% aid from the belt which allows for a heavier load. This dovetails into my next point which is that Squats are a HIPS & LEGS exercise, not a core exercise. Wearing a belt, allows you to place MORE LOAD on the hips and legs, while supporting the core. So the hips and legs get stronger when working under the heavier loads provided by the belt support. This seems a fairly simple argument. So if you want to squat to increase strength in your legs and hips – wear a belt. It’s the same argument for not pulling your Deadlifts Double Overhand. Deadlifts are a hips, legs, and back exercise. Not a grip exercise. However, some lifters insist on using a double overhand grip for the sake of “purity” (or something?) as opposed to using a hook grip, mixed grip, or even straps. All of which are preferable to lifting submaximal loads double overhand, where grip is the limiting factor. The grip is a by-product of training the deadlift, but it is not the primary purpose of the exercise and should not be the limiting factor in deadlift training. Here is the other – purely anecdotal – argument…..heavier belted squats make your beltless squats go up, whether you ever train beltless or not. There is an impressive video of Dan Green Squatting 635×10 beltless online. Did he achieve this feat of strength by training beltless? or by pushing his belted squat up over 800? My argument is that it’s the latter. You can probably assume that your beltless squat is largely going to remain some FIXED percentage of your belted squat…..let’s call it 90% although it could be more or less. If you wanna get that beltless squat up, make it 90% of a larger number. For instance, let’s assume you can Squat 315 x 5 with a belt. And without a belt you can Squat 285 x 5. You want to get that beltless number up to 315×5? Then push your belted squat up to 345 x 5 and you’ll hit 315×5 without a belt, without ever training beltless. And in the process your legs and hips are stronger since you made them Squat 345×5. Belts vs Wraps / Sleeves / Briefs / Suits So remember earlier when we said that Squats are a hips and legs exercise and not a core exercise? This is an important point when it comes to supportive equipment. Belts help to support the core while the hips and knees GENERATE THE FORCE on the barbell without the aid of any extra equipment. When you add wraps, heavy thick knee sleeves, or certainly squat briefs or suits, you cross the threshold of DIRECTLY influencing force production. Force production is generated at the knees and the hips and when you add serious magnitudes of compression with thick materials around the knees (wraps or thick sleeves) or the hips (briefs or suits) you are influencing the weight on the bar with help from material that isn’t your own muscles. These pieces of gear are helping to operate the levers of force production, rather than aiding in more efficient force “transmission” as we see in the use of the belt. And in my opinion this is a distinctive difference between the belt and everything else. So should you wear these items in training? Simple answer…..it’s up to you. I don’t have a problem with a guy wearing a light pair of sleeves if he’s old and creaky or has a history of knee injury. A little extra warmth and compression can keep you safe and healthy and pain free and won’t aid that much to your lifts. Wraps add a lot more than sleeves. A good rule of thumb is that you should be able to leave your knee sleeves on during your whole squat session. If they are so tight you have to pull them down to your ankles between every set or risk losing feeling in your feet, then your sleeves are too tight for training. You can make a case for the periodic use of knee wraps as a way to train overload for some stimulation of the nervous system, but “squats with wraps” have to be treated as an entirely different exercise and I would not ever recommend training in knee wraps regularly. I can see no reason for briefs and suits unless you want to compete in geared power lifting for some reason (back, back, back, back, take it!!!) The Squat Q&A: Mechanics, Belts & Assistance (Part 3) So in this last installment of our Squat Q&A, we’ll discuss another common question about Squats: “What are the best assistance movements for the Squat?” Of the Big 4 Barbell Exercises (The Squat, Bench, Deadlift, & Press) I feel like the Squat actually benefits the least from assistance exercises – especially if we are talking about lower stress / non-barbell / isolation type work. So whatever assistance exercises we are talking about using for the Squat, we’re mainly talking about barbell based variations of the squat. I’ll briefly go through a list of a few of my favorites and how I’ve had the best success programming them. In terms of programming, we’ll assume a very basic intermediate routine – using a heavy, light, medium full body training split, or a 4-day per week heavylight type split, and I’ll show you how I plug these exercises in. We’ll also assume that your “heavy day” or “competition” squat is the standard low-bar back squat. #1: High Bar Back Squat I like this movement with a slightly narrower stance, a deep range of motion, and often with a pause at the bottom. Ed Coan was a big fan of these, as back-off work after his heavy squats, and so that’s how I’ve generally used them as well. Very easy to just strip some weight off the bar after your heavy work for the day and knock out 1-3 sets. Deep high-bar back squats are tremendous for building up the Quads and I usually program them for sets of 8-10. This will build up the quads as well as increase your overall work capacity. These can be done for sets across or descending sets with shorter rest periods between sets. If you’ve never done this, just start with one back off set for 8-10 reps or you’ll struggle to walk the rest of the week. Add volume slowly over time as needed or as tolerated. Example Week Monday – Heavy Squat / Light Deadlift o Low-Bar Back Squat 5 x 5 x 405 o High-Bar Back Squat 1 x 10 x 325 o RDL 3 x 10 x 315 Thursday – Light Squat / Deadlift o Low-Bar Back Squat 3 x 5 x 365 o Deadlift 5 x 455 #2: Front Squat Similar to the High-Bar Back Squat in the powerful stimulus you get in the Quads, I usually use this for lower reps but more sets than the High-Bar Squat. And I really like Front Squats as a Light Day Squat variant. I also like performing Front Squats after Deadlifts, as the low back fatigue from the Deads doesn’t seem to interfere with Front Squat performance that much, and the CNS stimulation you get from heavy Deadlifts really makes the lighter front squat loads fly up with some good pop! at the top. Example Week Monday – Heavy Squat o Low-Bar Back Squat 5 x 5 x 405 Wednesday – Light Squat o Front Squat 3-5 x 3 x 315 Friday – Medium Squat o Low-Bar Back Squat 4 x 5 x 365 Example Week 2 Monday – Heavy Squat / Light Deadlift o Low-Bar Back Squat 5 x 5 x 405 o RDL 3 x 10 x 315 Thursday – Heavy Deadlift / Light Squat o Deadlift 5 x 455 o Front Squat 3-5 x 3 x 315 #3: Paused Squat Paused Squats are one of my favorite “medium day” exercises in an HLM routine. The loads are generally appropriate for a medium day level of stress, but instituting a brief 2-3 count pause at the bottom adds a greater degree of difficulty. You can also pause your light day squats, but usually on light days I’m not looking to make things really difficult by adding techniques like pauses to the program. I usually save these for medium days. Example Week Monday – Heavy Squat o Low-Bar Back Squat 5 x 5 x 405 Wednesday – Light Squat o Low-Bar Back Squat 3 x 5 x 285 Friday – Medium Squat o Paused Back Squat 5 x 4 x 345 #4: Paused Box Squat The advantage to the Paused Box Squat is that recovery from the pause on the box seems to be a bit easier than a dead stop pause without the box. The other bigger advantage to the box squat is the ability to really overload the posterior chain by sitting further back into the squat than the regular squat or paused squat will allow. Doing paused box squats correctly should really allow you to feel the hamstrings more so than any other squat variation. This also makes the box squat a good option for inclusion in your training if your deadlift needs a little stimulus. In my opinion, if you are not using the paused box squat to sit further back than in your normal squat, there is really no reason to use the box. The main drawback to the box squat is the dependency you can develop on the box for the feel at the bottom. I rarely recommend you use the box squat exclusively because it can ruin the feel of the bottom of the squat. Box squats are good for working around knee injury / knee pain and this is the only case where I’ll use box squats exclusively. Box squats can be used for regular straight sets of around 5-reps per set, or used for Dynamic Effort Training. Box Squats are great for a medium day squat variation. Example Week Monday – Heavy Squat o Low-Bar Back Squat 5 x 5 x 405 Wednesday – Light Squat o Low-Bar Back Squat 3 x 5 x 305 Friday – Medium Squat o Paused Box Squat 4 x 5 x 345 Example Week 2 Monday – Heavy Squat / Light Deadlift o Low-Bar Back Squat 5 x 5 x 405 o RDL 3 x 10 x 315 Thursday – Heavy Deadlift / Light Squat o Heavy Deadlift 5 x 455 o Dynamic Effort Paused Box Squat 10 x 2 x 325 (1 min between sets) #5 Pin Squats While some will use Pin Squats interchangeably with box squats in their programming templates, I have found that pin squats are quite a bit more stressful and more difficult to recover from quickly than a paused box squat. Pin Squats can be quite brutal on the quads and also the knees. Like other exercise variations that are paused in the rack (pin presses, rack pulls, etc) I’m usually careful about the frequency of the pin squat. While I really like the exercise, I typically don’t program them more frequently than every other week. Because I have found them to be on the high end of the stress spectrum, I usually program them on the heavy day during the week and then regular squats will be done on the light and/or medium day that week. Pin Squats really force the lifter to explode out of the hole and it’s damn hard to get a heavy barbell off the pins. This has the potential to build some serious strength. I have found that I like programming Pin Squats with clients using 5 x 5 in Ascending Sets rather than with sets across. This gives the lifter some decent volume, but less risk for overstressing them. This also helps them to really dial in the technique prior to the main top heavy set of 5. So if the lifter is aiming for a top set of 5 at 365, the work sets might look like this: 225 x 5, 260 x 5, 295 x 5, 330 x 5, 365 x 5. Example Week Monday – Heavy Squat / Light Deadlifts Low-Bar Back Squat 5 x 5, alternated each week with Pin Squats for 5 x 5 (Ascending) o RDL 3 x 10 Thursday – Light Squat / Heavy Deadlifts o Low-Bar Back Squat 3 x 5 o Deadlifts 1 x 5 o Those are really my main 5 that I would use regularly in programming. Of course there are other methods as well including specialty bars, bands, etc, but for most people reading this article, those 5 variations will give you plenty of variety to try and work with an improve upon over time. There are of course dozens of bodyweight and machine based exercises that also train the quads, hamstrings, lower back, calves, and abs. These types of exercises (ex: leg presses, step ups, lunges, leg curls, glute ham raises, reverse hypers, etc, etc) can be useful for building up your total training volume and your overall work capacity, and can be useful for some forms of hypertrophy specific training, but they aren’t going to do much in terms of actually improving your squatting strength. Unfortunately the only way to do that is with squats and very close derivatives of the squat trained heavy and hard. The Case for Front Squats Sometimes the strength and fitness world makes me laugh and shake my head. It seems like no matter the exercise there is always a debate or controversy regarding its utility, value, performance, or safety. Bench Presses are crowned “The King” of upper body exercises for one camp and are named wholly “non-functional” for another. Front Squats are definitely one of those exercises that puts people in “camps” of yays and nays. I generally try and take an objective stance with exercise selection and I avoid painting myself into a corner as a hard advocate either for or against any exercise. Does it make sense for the program? Does it make sense for the goal? Does it make sense for the person? No matter the exercise, we simply need to be able to justify it’s existence in our program. It can’t just be there because Coach X said he likes them. Our time and energy is too valuable to waste on exercises that don’t help us toward our goals. So we know that Front Squats are essential for Olympic Lifters. It’s a part of the sport. A skill that must be practiced and strengthened regularly But what about for the average recreational lifter? The power lifter? The athlete? Is there a role for the Front Squat? The short answer is “yes.” Let me start by saying that I never recommend front squats to novices who are focusing on trying to learn the low-bar back squat with correct technique. For most novices we are trying to get them to “unlearn” lifting with their chest out of the hole, and instead trying to teach them to drive “up” with their hips while holding a fairly constant back angle. I don’t like deviating from this teaching model for a novice. The front squat teaches “chest up” as a cue for coming up out of the hole……this can create some “technique confusion” in less athletic lifters. Until the low-bar back squat is mastered and technique is internalized, I stay away from front squats. However, for intermediate lifters I really like Front Squats as a light day Squat Variation. So I like Front Squats in addition to, not in place of regular heavy back squats. Some coaches like Mike Boyle and Dan John are “front squat only” advocates but I just think they are wrong, plain and simple. I don’t think they have a good model of teaching the back squat and have therefore defaulted to something they are more comfortable teaching. The front squat works less muscle and uses less load than a back squat. It’s more knee and less hip and I just can’t see how it’s a better strength exercise than a back squat. Unless we aren’t defining strength the same way. However the fact that the front squat uses less load and works less muscle is what makes it such a great exercise for an intermediate! As you guys know, I’m a big fan of Heavy-Light and Heavy-Light-Medium programming for intermediates. Light Days and Medium Days can be done two different ways. The first way is that the parent exercise (say Back Squats in this example) can simply be repeated throughout the week, but with less volume and lighter loads. An example: Mon: Heavy Back Squat 5 x 5 Weds: Light Back Squat 3 x 5 (-20%) Friday: Medium Back Squat 4 x 5 (-10%) The advantage to this approach is simplicity and practice through repetition. Especially if you struggle with form or technique, this approach will get you really good at squatting! The other approach is to use variations of the parent exercise as subs for the light and medium day, that by their nature constitute light and medium day exercises. As an example: Mon: Heavy Back Squat 5 x 5 Wednesday: Heavy Front Squat 3 x 5 Friday: Paused Box Squat 4 x 5 In this case, the Front Squat, even when trained heavy is lighter than the heavy back squat and produces about the same amount of systemic stress as does a lighter back squat. So here is the big question? ……Why bother with the added complexity of learning to front squat? Why not just squat light and keep it simple? My answer basically has two parts. First, I first and foremost value being strong. I’m not just interested in achieving a good Squat, Bench, and Deadlift for competitive purposes. There are lots of programs that “grease the groove” on just a few lifts with tons of volume and frequency for just the competitive lifts, and those programs work well in many instances. However, for the purposes of general strength, I like being strong on a broad base of different lifts. I find that when focus gets too narrow in terms of exercise selection that trainees lose out on the benefits of developing a broader base of strength that carries over better to a broader range of real life applications. I look at it like this….do you want to wrestle with an elite strongman or an elite powerlifter? Who do you want to hire to move your furniture? The point is that the elite strongman is probably comparable in strength to the power lifter in the Squat and Deadlift (maybe not the bench) but is probably far stronger across the board in a wider array of lifts and real world life events. So I take the same approach in my own training and that of my clients. When possible and effective – broaden the base of exercises if you can. The second part of this is that I like the mindset behind trying to actively get stronger on a lift rather than just training something light. When doing a “light squat day” we’re kind of just going through the motions. Generally working off of a set % that makes the light weight moderately challenging, but undoubtedly doable. It feels like practice instead of training. After a few years of training under your belt – how much practice do you still need? Been training for 5 years and still working on squat form? Come on. I’d much rather approach a training session like it’s a challenge. I want to chase progression. Placing the front squat on my “light squat day” enables me or my clients to train hard, with an aggressive mindset, chase new PRs, while still giving our systems a break with a lower stress workout. Let’s say you can currently Squat 365 x 5 x 5 on a Heavy Squat day. A light day at a 20% reduction in load would be something like 295 x 5 x 3. Can you front squat that? If the answer is “Hell NO! I’d be lucky to front squat 225 x 5 x 3!!!” Well then there you go….there is your project for the next couple of months! Do you think that driving your front squat from 225 to 295 over the course of a few months will help your Squat, Deadlift, and overall base of strength better than just squatting a weight over and over again you already know you can do??? You’ll have to try and see. But it’s something to think about. Pause Squat vs Pin Squat vs Box Squat As part of my power building program as well as my basic barbell program, at my gym and in my online coaching group I have my members do a lot of each of these movements as variations of the Squat. I like all 3 of them, but I think they each serve a different purpose. There may be other reasons why other coaches and trainees use them….so I don’t necessarily intend for this to be a comprehensive manifesto on the 3 squat variations, but instead, just some things to think about if you are considering introducing some variety into your squat programming. In my power building program we are currently running a conjugate type of program that includes a Max Effort Lower Body day as part of the 5-day cycle. On the Max Effort Day we typically do only variations of the Squat or the Deadlift. The primary Squat and Deadlift are performed on a separate day which is our volume / speed day. But on the Max Effort Day we work up to a 1-rep max on a variation of the Squat or Deadlift then follow that up with some back off sets based off today’s top single. I alternate every week between a Squat and Deadlift variation. For the Max Effort Squat day, we do a lot of pin squats and box squats. I also use the box squat for sets of 5 on max effort deadlift days as an assistance exercise. In my Basic Barbell program, we have a heavy squat day where I rotate reps weekly between sets of 8, sets of 5, and sets of 2. Then we have a light squat day later in the week. I give my members the option of simply performing light squats – or using a squat variation – such as pause squat, pin squats, or box squats. So what is the purpose and usefulness of each variation and why pick one over another? Pause Squats. Simplicity. No equipment is required, and you don’t have to mess with pin settings. Many of my members train in extremely bare bones garage gym environments and actually don’t have sturdy enough boxes to squat down to and don’t have thick bumper plates to stack up. Most have benches, which can be used for a box squat, but for many, the bench will be too high of a squat to be of much value. Some cages have very wide hole spacing and pin settings might be either too high or too low for a good pin squat. So if you want to keep variations down to the most utterly simple version possible….you just pause your squat in the hole for a 2-3 count and explode back up. Technical Refinement. If you have issues with the bottom of your squat (knees caving, back rounding, chest collapsing, inconsistent depth, etc) these can help. With a prolonged pause and a lighter weight a paused squat can really help the lifter get a feel for certain cues he or she may need to work on at the bottom of the squat Strength in the hole. If you have any of the above issues, holding the correct squat position isometrically in the bottom of the hole for a prolonged 2-3 second (or even 5 second count) can build up strength in the muscle groups that may be giving way under load. Speed Training / Dynamic Effort. If I’m prescribing lighter weights (say 60-70%) for speed work then I like to have my trainees pause briefly before initiating the ascent. I find that for most, this slight pause helps lifters be more intentional about generating maximum speed out of the hole while maintaining good form and consistent depth. Without the pause, some lifters have a tendency to cut depth off short in anticipation of the explosive concentric and/or just have issues with balance over the mid foot and things can get sloppy. Used on a “light” squat day, this is an excellent strategy to make a lighter weight serve a greater purpose other than just serving as a placeholder to maintain some volume and prevent detraining. I think the more advanced you get, the less value there is in simply having a “light squat day.” Make those extra sets and reps serve multiple purposes if possible. Pin Squats I find that pin squats are just a slightly different variation of a paused squat. I personally find them much harder than a pause squat. Power out of the hole. If you find yourself with a very low sticking point in the squat i.e. you get buried coming out of the bottom on heavy efforts, then pin squats might help you. You might think that when the weight is intercepted by the pins it allows you some sort of rest or reprieve at the bottom that would make the movement easier than a regular pause squat. But it’s really the opposite that is true. While you aren’t holding that isometric contraction as hard in the bottom like in a true pause squat…the pins absolutely kill the stretch reflex. Unless you are not pausing long enough or bouncing off the pins. Don’t do that. Pause and pause for at least a few beats to allow for the stretch reflex to be mitigated as much as possible. That’s the idea here. Without the stretch reflex you have to volitionally generate a ton of power out of the bottom of the squat. In fact, the pin squat might be equally or even more effective as a Deadlift supplemental movement as it is for squats. The old University of Houston power lifting coach John Hudson, was an advocate of pins squats as the primary movement which built explosive leg drive off the floor in the deadlift – even more so than a deficit deadlift which tend to get all the credit in this department. His results as a coach and lifter make me think he knew what he was talking about Learn to grind a slow rep. Heavy pin squats move slow. All heavy squats move slow – by definition – but pin squats seem like they rarely ever get out of first gear. This has some value. If you are a lifter that struggles with the mental and/or physical ability to really grind through super slow heavy reps, the pin squat can help you build up your skill set in this department without forcing you to actually train your competition squat maximally all the time – which can have diminishing returns done too frequently. Quad work for low-bar squatters. For the most part, the pin squat allows you to keep the same mechanics as you would in your regular low-bar squat. The one minor change is that it kinda kills your ability to drive up out of the hole with your hips as we would normally teach a low-bar squatter. Pronounced hip drive in a pin squat can have the effect of causing the lifter to rotate his ass up while his chest stays down. This is not good leverage and can even be dangerous. We don’t want to goodmorning the bar off the pins, but more likely you will just get stuck. The pin squats forces you to drive straight up into the bar and makes this variation of the low-bar squat much more quad dominant. If you want to find out for yourself, just do a bunch of pin squats and your quads will be way more blown up than normal and your soreness pattern the next day will also reflect this change in mechanics. So if you have under developed quads relative to your ass and hamstrings you might make pin squatting a more regular part of your training. Box Squats Overload the Hamstrings. I have a slightly different opinion on the Box Squat than many. I actually don’t believe they help you build that much power out of the hole if you take them down to your normal squatting depth. I understand that many do not share this opinion and that is fine if their experience has been different than mine. But for a raw squatter who puts too much emphasis on box squatting, I find that he or she will actually lose the feel of the bottom of the squat, especially in the absence of regular “free squats.” For power development out of the hole – I prefer pin or pause squats. Instead I find that the key benefit of the Box Squat is strengthening of the hamstring – if you do them right. The benefit of the Box, is that is allows you to sit much further back into the squat than you could in a regular squat or off the pins. With the hips way back and the shins nearly vertical you put an enormous load onto the hamstrings in both the eccentric and concentric portion of the squat. If you have underdeveloped hamstrings, more box squatting can help build up the hamstrings. And you can do so in a way that is more effective than isolation movements like leg curls or glute ham raises, and that doesn’t put as much stress on the lower back. I love RDLs, Stiff Leg Deadlifts, and Goodmornings for the hamstrings, but you can only do so much heavy hip extension variations in a given week before you exceed the ability of your low back to recover. Box Squatting is less low-back intensive while still giving a major dose of heavy eccentric and concentric work to the hamstrings. Work around injury / inflammation. For my clients that tend to build up inflammation in the knees easier than others (many of my older clients) or have a knee injury – box squatting can allow you to take a lot of pressure off the knees and shift even more of the load onto the hips. A few years ago when I had a non-lifting related (don’t ask!) quad tendon strain, I could not perform a regular weighted squat for many weeks. However, I was able to box squat with very minimal pain, and over the course of a few months, built my box squat up from a slow painful 135 lb squat to over 500 lbs without reaggravating the injury. There are so many ways to program these lifts into your training plan that it would constitute an entirely new article or even series of articles. I don’t think you need to arbitrarily and randomly toss all 3 variations into your training program at once. Instead, think about your biggest struggles with your squat and figure out which variation might contribute most in your program. Deadlifts Deadlift Programming & Assistance There is nothing quite as frustrating as a Deadlift that just won’t budge. Every lifter that has been training for a while has experienced that day where he locks into to pull his 5-rep work set, but instead the barbell just sticks to the floor. Instead of 5 reps, you maybe get 5 inches. It’s the kind of thing that makes you check the plates on the bar to make sure you didn’t accidentally load a few extra 45s by mistake. It’s defeating, but it happens. Relative to my squat, I’ve never been a great deadlifter. My presses and squats have always responded well to pretty basic programming, but I’ve always had to get a little creative to get the deadlift to keep moving, and I’ve had plenty of clients in the same boat. Over my 10+ years of coaching the barbell lifts I’ve tried, failed, and succeeded with several different approaches to deadlift programming. In this article I’m going to outline one method that requires quite a bit of work outside of just deadlifting, but generally works well, especially over a long period of time. You’ll need to be able to devote 3-days per week to this approach, and one top of this you can layer in your Bench and Press training as you see fit – either on separate days of the week or you can add some pressing to any of these 3 days. Monday – Deadlift Day Exercise #1: Deadlifts You’ll start on Monday with regular conventional deadlifts for 3 work sets. Each week you will alternate between sets of 8, sets of 5, or sets of 2. I suggest starting this program at 70%1RM for sets of 8, 80% 1RM for sets of 5, and 90% 1RM for sets of 2. Every time you complete the 3 week cycle you will add 5 lbs to each week for the next cycle. Exercise #2: (Choose One of the Following) Box Squats, Pin Squats, Front Squats, Stiff Leg Deadlifts, or Deficit Deadlifts. You will perform 3 work sets for 8 reps. For experienced lifters I recommend changing the exercise up every week. For intermediates I would pick one and stay with it for several weeks until you are struggling to complete 3 sets of 8 reps. At that point switch movements. Exercise #3 (Choose One of the Following): 45 degree back extension, 90 degree back extension, glute ham raises, lying leg curls, or reverse hypers. The point here it to build work capacity in your posterior chain with a low stress movement. I suggest 3 work sets of 15-20 reps. This will help you build the tolerance for all the deadlift volume in this program. Wednesday – Upper Back One the upper back day you will do anywhere from 1-4 movements depending on your work capacity and how you have your week scheduled. You will always do Barbell Rows as your 1st or 2nd movement of the day. Second priority would go to Pull Ups which you should probably do before you Row if you are going to do both exercises. Third and/or Fourth would be some shrugs and/or another row variation such as DB Rows, T-Bar Rows, or Seated Cable Rows. I recommend 3 work sets for each exercise, all in the 8-10 range. Use straps as needed to save your grip and keep the focus on building your back, not your grip. Friday – Squat Day Exercise #1: Squats Program your Squats the same way you did the Deadlifts with my 8-5-2 scheme. 3 work sets, rotating through the different rep ranges each week. Exercise #2: RDL or Goodmornings After squats perform either an RDL or a Goodmorning. If you know how to do both, then switch on a weekly basis. If you don’t know how to do a Goodmorning then simply perform RDLs. Again 3 sets of 8 reps. Every 9-12 weeks you will drop this exercise completely in preparation for a deadlift testing day on the following Monday. Exercise #3: (Choose One of the Following): 45 degree back extension, 90 degree back extension, glute ham raises, lying leg curls, or reverse hypers. Again 3 sets of 15-20 reps and I suggest a different exercise than what you used on Monday. Testing and Deloading After 3-4 cycles of this (9-12 weeks) you will test a new 1RM on the Deadlift. The testing day should fall on a week that would normally have your performing 3 sets of 2. You will test the 1RM in place of the 3×2 workout. After the 1RM Deadlift on Monday I want you to skip exercise #2, and only do the light posterior chain work. On Wednesday, just do light and easy upper back work. Maybe Lat Pulldowns and Seated Cable Rows. On Friday you will Squat 3 moderate sets of 5, skip the RDLs or Goodmornings again, and perform some light posterior chain work. The following week you will restart the program with sets of 8, recalculating off of your new 1RM or simply adding 5-10 lbs from where you left off in the previous cycle. Simple Deadlift Program That WORKS Sometimes we like to outsmart ourselves with complexity, and often we wind up doing more work and more thinking than we need to, when less work will get the job done just as well. I’m currently coaching a young lifter who is working his way through law school and doesn’t have a lot of time or energy to devote to weight training, although he still makes it into the gym 2-3 days per week pretty regularly. And he busts his ass while he’s there. He’s also very underweight (only about 140 pounds) but he seems pretty happy at this body weight. He knows he’ll be stronger if he gains weight, but I’m not one of those coaches who forces the issue all the time. Your weight is your decision not mine, and I’ll figure out a way to get your lifts up regardless. It might be slow and tedious, but we’ll get them to move. So for the last several months we’ve been using a very simple method for his deadlift program, and just last week we hit our 405 deadlift goal. Not bad for a buck-40 lifter. On Thursdays we Press & Deadlift. And that is our only Deadlift session of the week. No light days, no assistance work. 3 sets of Deads once per week. Just a few weeks ago we tested the Deadlift and he pulled 385. So we set up his next training cycle like this: Week 1: 5 x 5 x 75% Week 2: 3 x 3 x 90% Week 3: 3 x 5 x 80% Week 4: 2-3 x 2-3 x 95% Week 5: 3 x 4-5 x 85% Week 6: New Single We’ve done this cycle twice now, each time, we’ve hit a a new 20-lb PR in Week 6. The first 3 weeks are generally not too hard, and in fact, in this second cycle we actually wound up pulling 8-reps in the last set at 80% in Week 3. The 95% week is definitely the hardest week and so I build in some flexibility. We can do as little as 2×2 or as much as 3×3 depending on bar speed. Week 5 is somewhat hard, mainly from the fatigue of the 95% week and so again, we have some flexibility in rep range. I’m aiming for 3×4, but if he feels good, I let him pull 5. No AMRAP sets in Week 5 though. We save any extra energy for week 6. So far this cycle has paid off and now I’ve got a few other clients running it as well and so far so good. Is this right for you? No way to tell, but if your Deadlift is stuck, and you’ve overcomplicated your programming (again) then try this out and see what happens. When in doubt…..increase effort and simplicity. Deadlift Injuries? 4 Step Safety Check Of all the exercises that get a bad rap in regards to injury, the deadlift might stand alone as the lift that receives the largest share of unwarranted blame. Can you get injured on the Deadlift? Of course. And many people do. But I don’t feel like the Deadlift is inherently dangerous when done correctly. I’ve been teaching clients how to Deadlift at Kingwood Strength & Conditioning for over 10 years now. I can count on one hand the amount of injuries we have had here at the gym from the Deadlift. I’ve coached hundreds of clients (maybe even thousands now) how to Deadlift – most of which were not elite athletes, and most of which were over 40 years of age! If Deadlifts were just inherently dangerous I’d have racked up alot more injuries by now! Furthermore, the reason people get injured on the Deadlift is rarely if ever due simply to load. It’s due to incorrect technique. This can happen on heavy loads or lighter loads. In fact, most of the injuries I’ve seen have been at submaximal weights. One of the reasons for this is that people get sloppy with their warm ups at times and on their way up to that 405 workset, they don’t give the 315 warm up enough respect. You have to practice perfect technique even at lighter loads. It’s that, coupled with the fact that sometimes very heavy weights won’t actually move much when you demonstrate poor technique. Light weights will allow you to move them, even with poor technique, and there is enough time under tension with bad mechanics to cause an injury. Really heavy loads just have a way of gluing themselves to the floor when you try and pull them wrong. So here is your 4-Step Deadlift Safety Checklist to avoid injury: #1: Don’t Get the Bar Forward Of Mid-foot This most often happens when trainees sink their hips/ass down too low at the start position. Whenever you try to “sit” down into the deadlift and the hips get too low, it will cause the knee angle to close, and as a result the shins will travel forward. When the shins travel forward it can push the barbell forward of the midfoot. For most beginners especially the hips will start out higher than you think they should be in the correct starting position. If in doubt, video yourself from a profile shot and see if the barbell is in line with your midfoot (the knot on your shoelaces) and also that your scapula is over the barbell and not behind the barbell. So we want a straight vertical line drawn from the scapula through the barbell through the mid-foot. If the hips are too low the scapula will be behind the barbell, the torso will be too vertical, and the shins will be angled too far forward thus pushing the barbell out over the front of the foot. When you try and lift from this position the bar will try and leave the ground while it’s out over the front of the foot and this can cause back injury. Never attempt to pull a bar off the ground that is out over the toes. Even just a few inches forward of mid-foot is dangerous. If you do this right, and do everything else wrong you’ll probably be okay. But this is the number one cause of injury that I have seen. #2: Don’t Shoot Your Hips Up Early I see this alot when lifters are attempting a heavy weight, even if it didn’t manifest itself on the warm ups. In an effort to pull the bar with force and speed, the lifter’s body misinterprets the cue, and instead of exploding the bar up off the ground, they shoot their tailbone straight up into the air and THEN try and pull the bar off the ground. This error essentially turns a deadlift into a stiff-leg deadlift and causes the lifter to pull with nothing but hamstrings and back without any contribution from the quads. When you try and pull a maximal load with less muscle mass it can result in injury. More often it just results in a missed rep or burning up more energy than you needed to and so what should have been a 5RM becomes a 2RM. Focus on keeping the hips down (not too low or you encounter mistake #1) and breaking the bar off the ground with the quads. Again, a quick profile video with your cell phone can identify this error rather quickly. #3: Get Your Back Into Extension I know, DUH! Extending or “arching” your back is Deadlifting 101 but many fail to do it even so. Sometimes this is just do to negligence. Maybe focused on fixing some other form error, they simply forget to do the final simple step that occurs before you pull which is to set the back into extension. For others, setting the back into extension, or arching, is just difficult. That mind-muscle connection with the lumbar spine is simply not established and without constant verbal and tactile cues the lifter may not be able to tell if he or she has indeed set their back. You must practice this on all warm up sets and even between sets without load until it becomes habit. Some older men especially may not have the ability at all to achieve spinal extension that is pleasing to the eye. Their back may be flat at best or even always have some small degree of rounding. As long as the lumbar muscles are actively held in tight contraction a very small degree of rounding may be acceptable BUT you must be very careful with this scenario and I do not recommend that trainees deadlift maximal loads in these situations. I often advise these types of trainees to elevate the barbell off the ground by 1-2 inches using cut out rubber mat squares or squares of plywood. Sometimes (not always) this helps get the trainee into a better pulling position. Another option is a rack pull with the pins set very low in the rack. Just enough room for the trainee to get into a safe start position. #4: Lower the Bar Correctly Some trainees have a picture in their brains of lowering the barbell between reps with a nearly vertical torso as they “squat” the weight down back to the floor. When you do this, the knees will travel forward and then the barbell will have to loop out around the knees before it hits the floor. Doing so will get the barbell waaaaay out in front of the mid-foot as you lower it. This can result in injury with even very light loads. Lower the barbell down to the floor by pushing the hips back and letting the barbell “fall” in a line that is over the midfoot. Keep your knees out of the way. The barbell should NOT hit the top of your knees on the way down. The deadlift does not have a slow eccentric. But it’s not a complete free fall either. Guide the bar down to the floor but you shouldn’t be under a lot of tension. By trying to “squat the weight down” you will be forced to lower the bar with a pronounced eccentric, the bar will be out over the toes, and your starting position for the next rep will be off. Your hips will be too low and that puts you in the scenario where mistake #1 occurs. Deadlift Variations – What, When, Where, How Everybody loves variety right? Sometimes variety is great for training, sometimes it’s the death of your training. Variety just for the sake of variety is not really a productive way to go about things in the gym. The caveat to that, for me, is on the margins – when we’re dealing with exercises that are not part of our primary group of core barbell lifts, then a little variety is fine. It keeps things fun and interesting in the gym without sacrificing productivity and efficiency. Does it matter if we barbell curl or dumbbell curl? No. Does it matter if we train triceps with a cable machine or an ez curl bar? Not really. Sit ups or leg raises? Who cares. But what about variety on the main lifts? Squats, Presses, and Deadlifts. What’s better – switch things up all the time or stay consistent? It seems like I write the next two words in just about every article I write – it depends. For novices we know that the basics are plenty. 4-6 exercises repeated over and over again, add a little weight each time, done. But it gets trickier as an intermediate and advanced lifter. It’s not as simple as just adding a little weight to your sets of 5 each time you go into the gym. As an early intermediate, we don’t train much variety on the exercises. Most good strength coaches I know have found that early intermediates still need a bit of frequency on the core lifts for optimal progression. Maybe not heavy 3 days per week, but most do better with at least one heavy session per week on each of the main exercises, and most probably do better on 2 sessions per week on the main lifts, even if one is heavy and one is light. It varies from lifter to lifter based on age, absolute strength, overall goals, etc. But basically the variables we manipulate for early intermediates tend to be in terms of sets/reps/frequency, but not so much exercise selection. However, after many months of early intermediate style programming, you start to run out of set/rep manipulations for all the exercises. It’s helpful to have some other variables to play with to keep a lifter progressing and growing. That’s where we get into exercise selection. Basically the way I think about this is by breaking things down into 2 different categories: Variants & Assistance. To me, assistance work is your “weak link” training. Some will say that if you just do the primary barbell lifts often enough you won’t have any weak links. I disagree. Most assistance work is isolation type work (though not always), it’s done for higher reps and usually involves apparatus other than a barbell – dumbbells, bodyweight, cables, machines, etc. But over time, I think all later stage intermediates and advanced lifters do better when they regularly perform some assistance work to build muscle mass and strength in specific areas of the body that can help in the performance of the primary barbell lifts. Then we come to lift variations. These are exercises that mirror their parent lift both in performance of the lift and in load. These include all sort of variations performed for partial ranges of motion inside a rack, variations that use accommodating resistance (bands and chains), the use of specialty bars (safety bar squats, axle presses, etc) or even just changes in the way we carry the bar (front squats, close grip bench, etc). Lift variations are an important component of long term programming, but are trickier to work with than assistance exercises. Why? Well, because they mirror the parent lifts so closely they create a lot of stress. Stress is a good thing, but when overdosed or mismanaged it can screw up the program. You don’t just haphazardly throw in some Rack Pulls at the end of the workout the way you might haphazardly throw in some bicep curls. It has consequences for the rest of your week, or even the rest of your month. So in this article, let’s look at some popular Deadlift Variations. The purpose of this article is NOT a “how to” for the actual mechanical performance of these exercises. This will simply be a short expose of how I like to best utilize some of these variations in a client’s programming. Deadlift Variant Category #1: Partials / Top End / Overload These types of variations are highly stressful. Because they actually use more weight than a deadlift they are quite taxing on the nervous system. These movements also tend to place a high load on the lower-back and should be used with caution. Rack Pulls / Block Pulls Rack Pulls and Block Pulls allow us to pull some very heavy loads for a reduced range of motion. This has the benefit of being extremely stressful to the central nervous system (i.e. we get good at straining against super heavy weight) and also directly targeting the lumbar muscles in a way that no other exercise even comes close to. The downside to Rack Pulls and Block Pulls is the same as the upside – they fry our CNS and our lower backs. For this reason, they must be used with extreme care. Frequency must be limited to every other week at most, although I think once every 3rd week might be even better for longer term usage. When you go all out on a Rack Pull it takes a while to recover. I’ve seen guys come in and pull 600×5 on and the following week they can’t budge 500 off the pins for a single. You can’t do them heavy weekly. Rack Pulls should be rotated with regular deadlifts or with other deadlift variants explained in this article as part of a rotation of movements that get included in a lifters “heavy” pulling day. For volume, 1-2 sets is optimal. And this would be 1 heavy set in the 1-5 range followed by a back off set of 5-8 reps at a reduced load. If each set is maximal or near maximal, I can’t see a reason to do more than 2 sets of Rack Pulls. So even though Deadlifts are technically lighter than Rack Pulls, you could never set up a Rack Pull as a Heavy Day, and a Deadlift as a Light Day. Way too much stress in a single week for most lifters. Example #1 (4-Day Texas Method) Week 1 Week 2 Monday – Intensity Squat / Light Pulls Squat 5RM Power Cleans 5 x 3 Monday – Intensity Squat / Light Pulls -Squat 3RM -Power Snatch 5 x 2 Thursday – Volume Squat / Heavy Pulls Squats 5 x 5 Thursday – Volume Squat / Heavy Pulls -Squats 5 x 5 Deadlifts 1 x 5 -Rack Pulls 1 x 5 Example #2 (Heavy – Light – Medium) Week 1 Week 2 Monday: Heavy Squat 4 x 5 Medium Press 3 x 5 Medium Deadlift: Stiff Leg Dead 3×5 3 Monday: - Heavy Squat 4×5 - Medium Press 3×5 - Medium Deadlift: Power Clean 5 x Wednesday: Light Squat 2 x 5 Bench Press 4 x 5 Light Deadlift: Power Clean 5 x 2 Wednesday: - Light Squat 2×5 - Bench Press 4×5 - Light Deadlift: Power Snatch 5×2 Friday: Friday: - Medium Squat 3×5 - Heavy Press 4×5 – Heavy Deadlift Rack Pulls 1x5 Medium Squat 3 x 5 Heavy Press 4 x 5 Heavy Deadlift 1 x 5 Rack Pulls and/or Block Pulls could also be used as a back off exercise immediately following a set of heavy conventional deadlifts. For instance, the lifter might perform 1 set of 1-5 reps off the floor and then move the barbell up onto some blocks about 6″ off the floor. Following a 5-10 minute rest period and an adjustment of the load, he might pull a set off the blocks for 3-8 reps in order to train the top end of the lift. Banded / Reverse Band Deadlifts Although set up differently, both ways of using bands to deadlift change the load at the top of the lift. Banded Deadlifts and especially Reverse Band Deadlifts should be used like Rack Pulls / Block Pulls as “heavy day” variations that are programmed in place of regular heavy deadlifts during the week. Assuming the lifts are being trained hard and heavy, banded and reverse band deadlifts do not fit into a light or medium training day. Banded Deadlifts especially make an excellent way to perform back off work after regular deadlifts. It’s quite simple to strip some plates off the bar, throw a band over the top of the barbell and perform 1-2 additional sets in the 5-8 rep range. Especially if the lower back is considered a weak point in the lift, banded deadlifts as a standalone heavy day exercise or as back off work is an excellent choice. Speed Work Banded Deadlifts make an excellent choice for Dynamic Effort or Speed Work. My favorite way to perform speed work is with about 60% of my 1RM plus some light band tension. I’m not a fan of very heavy band tension for heavy work or speed work if you are a raw lifter. But 5-10 singles at 60% + light band tension is an excellent formula to increase power. If used in this context, I’ve found that Dynamic Effort Deadlifts are suitable for medium day type work and can be used with heavier deadlift versions later in the week. Example (Heavy – Light – Medium) Week 1 Monday: Heavy Squat 4 x 5 Medium Press 3 x 5 Week 2 Monday: -Heavy Squat 4×5 -Medium Press 3×5 Medium DL: Speed DL 10x1x70% 10x1x60%+mini bands -Medium DL: Speed DL Wednesday: Light Squat 2 x 5 Bench Press 4 x 5 Light Deadlift: Power Clean 5 x 2 Wednesday: -Light Squat 2×5 -Bench Press 4×5 -Light Deadlift: Power Snatch 5×2 Friday: Friday: -Medium Squat 3×5 -Heavy Press 4×5 –Heavy Deadlift Rack Pulls 1x5 Medium Squat 3 x 5 Heavy Press 4 x 5 Heavy Deadlift 1 x 5 Deadlift Category #2: Extended Range of Motion Extended range of motion variants are obviously those that target certain links in the deadlift chain for greater stress by increasing their range of motion by altering the mechanics of the lift. Generally these lifts are done with lighter loads than a regular conventional deadlift and with the exception of one, seem to be less stressful overall, making them good candidates for light/medium pulling days for some lifters. Stiff Leg Deadlifts / Romanian Deadlifts / Goodmornings All 3 of these deadlift variations place a tremendous amount of stress on the hamstrings. If you need extra work on the hamstrings, you need to be doing at least one of these exercises. They also hit the lower back hard (although not as hard as rack pulls). Stiff Leg Deadlifts (SLDLs) and Romanian Deadlifts (RDLs) often get used interchangeably from a terminology standpoint. Technically, the difference is that an SLDL starts from the ground and is de-weighted between reps on the ground like a conventional deadlift. RDLs start in the hang position, usually pulled out of the rack about thigh height, and use a stretch reflex in the hamstrings to return to the top. Some people only take RDLs down to their knees…..I personally do not see the point of this. If you want a partial range of motion, do a Rack Pull. It will work better for partials. RDLs are meant to train the hamstrings and hamstrings are trained better when they are taken through a LONG range of motion and STRETCHED DEEPLY at the bottom of the rep. That’s why I prefer SLDLs or RDLs for a full range of motion (plates hit the floor), or even better…..I like to stand on a small elevated platform (2-4 inches) for an increased range of motion and deeper stretch in the hamstrings. SLDLs and RDLs make excellent choices for light/medium day pulling variants with a regular heavy deadlift day later in the week. SLDLs and RDLs are best trained for sets of 5-8 repetitions for 1-3 heavy work sets. I don’t like putting the hamstrings in a maximally stretched position with insanely heavy loads which is why I don’t often have clients perform SLDLs or RDLs for less than 5-reps. My personal favorite use for an SLDL is as back off work after regular heavy deadlifts. This is a great way to add volume to a heavy deadlift session without frying your nervous system for the next week. After the completion of a heavy deadlift set in the 1-5 range, its simple, and very logistically efficient to strip off a few plates and perform 2-3 additional sets of stiff leg deadlifts in the 5-8 range. Three Example Uses of an SLDL: 4-Day Texas Method Example #1 Monday – Intensity Squat / Volume Deadlift Squat – 5Rm Stiff Leg Deadlift 3 x 5 Thursday – Intensity Deadlift / Volume Squat Deadlift – 5RM Squat 3 x 5 4-Day Texas Method Example #2 Monday – Volume Squat Squat – 5 x 5 Thursday – Intensity Squat/Intensity & Volume Deadlift Squat 5RM Deadlift 5RM Stiff Leg Deadlift 2 x 5 The second example is one of my favorite protocols for lifters of 40. Its how I set things up in one of my featured programs: Strength & Mass After 40. On a 3-Day Heavy-Light-Medium Program…. Monday (Heavy) – Deadlift or Rack Pull 1 x 5 Wednesday (Light) – Power Clean or Power Snatch for 5 x 2 Friday (Medium) – Stiff Leg Deadlift 3 x 5 Goodmornings kinda looks like a squat variation to a lot of people, but they are technically a deadlift variation. The only similarity they have to a squat is the position of the barbell across the back, but mechanically they are much closer to deadlifts. Goodmornings, done correctly probably stress the hamstrings more than any other movement. A few tips for Goodmornings: 1. Do them deep. Take them down to torso at parallel with low back in hard extension. Lower them to pins in the power rack and briefly pause. This will ensure you get to parallel each and every rep if you set the pins up at the right height. 2. Use a cambered bar or safety squat bar if you have one. A traditional barbell will keep rolling up your neck and is a general pain in the ass although it still works. My favorite bar for these is a Cambered Bar but Safety Bar is good too. Much easier to control when the weight gets heavy. 3. Train in the 5-8 range for 2-3 sets across. Deficit Deadlifts Whereas SLDLs and RDLs manipulate the range of motion of a deadlift in order to place extra stress on the hamstrings, deficit deadlifts place extra stress on the quads. By standing on a 2-4 inch block and doing regular deadlifts, the trainee is forced into a deeper squat position prior to initiating the exercise. If you need a little more horsepower breaking the barbell off the floor on a conventional deadlift, this is a tremendous exercise to try. It is very important to NOT turn this exercise into a stiff-leg deadlift which is easy to do if you get sloppy with form. The idea is to keep the quads engaged in the movement for a prolonged period of time, so keep your butt down, your chest up, and drive you and the barbell straight up! Don’t let the ass come up first and turn this into an ugly SLDL. It happens all the time. Deficit Deadlifts can be used in a variety of ways in your programming. These are very very stressful however, and I really do prefer that trainees use these on a heavy training day. I would not advise attempting to make heavy deficit deadlifts into a light or medium day exercise. It’s simply too much for the long term in my opinion. Deficits can be used in place of regular deadlifts on an every other week rotation, or as part of a longer series of 3-5 deadlift variants that all work across the heavy pulling day. Deficit Deadlifts also make an excellent choice for back off work after regular deadlifts. After a set of heavy deadlifts, you can strip about 10% off the bar and do 1-2 sets of deficit deadlifts to gain some volume. Deficit Deadlifts can be trained in a variety of rep ranges. For a very heavy day, top sets of 1-5 reps are appropriate, and for back off work, sets of 5-8 work well. In Summary…… So why do we make things so complex? If I just want a bigger deadlift why don’t I just do deadlifts? For some people this works. They make great deadlift progress simply by manipulating sets/reps/frequency. For others there will be a physical and sometimes mental/emotional need to do something different. When you deadlift gets legit “stuck” and you can’t make progress, I’ve found that the best method of unsticking the lift is to spend some time setting some PRs on deadlift variants that carry over well to the conventional deadlift. In other words – take your Stiff leg Deadlift from 315 x 5 to 365 x 5. Take your Rack Pull from 455×5 to 500×5. Take your Deficit Deadlift from 365×5 to 405×5. Even if you did just those 3 exercises for several months and didn’t Deadlift at all, I can just about guarantee a new Deadlift PR when you get back to pulling conventional. Goodmornings vs RDL vs SLDL One of the most common questions I get on my forum over at StartingStrength.com is something along the lines of: “I want to build up my hamstrings and lower back to help with my deadlift. But I’m confused about which assistance exercise to use? Goodmornings, Romanian Deadlifts? Stiff Leg Deadlifts? They all seem kinda the same? Is there any reason to use one over the other?” To be clear, there is never one right answer. As in most cases, the correct answer is “it depends.” But before we get into when or why to use each one of these, let’s get our definitions straight so we are all on the same page. Goodmornings For most people reading this post, they will at least be somewhat familiar with the mechanics of a goodmorning. Bar on the back like a squat, push the hips back and allow the torso to travel forward until the torso is roughly parallel with the floor. In this position the barbell will be a good deal forward of the middle of the foot, so the goodmorning forces the posterior chain to work through a range of motion where leverage is the least favorable (compared to RDLs or SLDLs). It also forces the hamstrings to work through the longest range of motion. Because of this, the goodmorning probably creates the most amount of hamstring soreness at equivalent volumes and intensities. While soreness is not everything, it’s probably our best indicator of which muscles groups are receiving the most stress from our assistance exercises. Goodmornings will also use significantly less weight than the other two deadlift variants. An important point to remember later. Stiff Leg Deadlifts (SLDLs) vs Romanian Deadlifts (RDLs) The difference between these two exercises probably creates the most confusion for strength trainees. Often the names are used interchangeably, but there are some important distinctions to be made even though the basic mechanics are almost identical. The most important distinction between the two exercises is where the movement begins. The SLDL begins on the floor, from a deadstop, just like a regular deadlift. Ideally, each rep is paused on the floor and completely deloaded between reps, again, just like a regular deadlift. RDLs begin from the hang position – ie. from the top. Generally the bar is taken out of a rack or off a pair of stands about thigh height. The rep begins when the bar is eccentrically lowered and the lifter will take full advantage of the stretch reflex between reps. This can mean stopping at some point around the knees or midshin and coming back up, or even doing a very light touch and go off of the floor (not a bounce). For this reason, RDLs can generally be done with the most weight at equivalent volumes and intensities. Originally, RDLs were done in the Olympic lifting community to strengthen the second pull. So most of the time, the weight was lowered to about knee height only. This is perfectly acceptable, but it is common to take the weight down further for increased ROM. In fact, it is common in both the RDL and SLDL to stand on a small elevated platform of 2-4 inches for increased range of motion and to make the mechanics even more difficult. So which one to use and why? – How I program them for my clients. So if I have made the determination that one of my coaching clients might benefit from one of these exercises, I look at a couple of things: First, where in the structure of their program will this exercise go? Generally my clients are on programs for 2, 3, or 4 days per week, and exercises may be arranged in a myriad of different ways. I am usually working with time constraints on how long an individual workout can last, and if I am working with a private client in my studio, there are often logistical considerations that are made in the interest of time. Second I ask, “Am I looking to ADD stress or REDUCE stress on a particular client?” If I want to add stress to a client’s routine, then I will often add in 1-3 back off sets directly following his heavy deadlift sets. My preference is to use an SLDL. We simply strip some weight off the bar and go right into the back off sets. It’s quick and easy. An alternate way to add stress/volume to his pulling program is to place one of these exercises on an alternate day of the week. Perhaps our lifter has a heavy squat day on Tuesday and a heavy deadlift day on Friday. In this scenario we would add in one of these movements after squats. For me, the choice would almost always be goodmornings. Again, quick and easy is always a winner. Simply strip some weights off the bar and you are ready to go. No additional set up, no change of location. Time saved. Goodmornings also make a good choice here because they are, by nature, lighter. A strong lifter may have a very difficult time pulling heavy RDLs or SLDLs on Tuesday and then trying to pull heavy from the floor again later in the week. Goodmornings don’t take quite the same toll on a lifters recovery capacity, but still deliver a powerful stimulus to the hamstrings. If I am l looking at reducing the stress on a lifter, then I may look at substituting one of these lifts in place of the deadlift on a given week. All these exercises can be used as a means of “deloading” from constant heavy pulling. But generally my exercise of choice is an RDL. The use of the stretch reflex makes the exercise a little easier to recover from than the SLDL (even at heavier loads) and often times the reason for taking the lighter week is to reduce stress on a client’s low back. I also feel that RDLs are a little bit safer. Violently breaking the weight off the floor without the use of the quads is a risky proposition for the hamstrings – especially for an older lifter. Eccentrically lowering into that deep stretch with an RDL reduces the chance of a pull or strain. Programming Stiff Leg Deads & Barbell Rows (a simple strategy) Two exercises I love programming for my clients are Stiff Leg Deadlifts and Barbell Rows. I’ve talked before about having a “reliability test” for your supplemental / assistance lifts, which basically means – how predictable is an increase on the parent / competition lift (in this case the Deadlift) if you have an increase in a given assistance exercise? For my money, the Stiff Leg Deadlift is one of those exercises. In my experience it is one of the most reliable / predictable of any assistance exercise for producing an increase in Deadlift strength. Make a legit increase here, and the Deadlift goes up. So, I like Stiff Legs in the program. But there is a downside. Mainly it’s that they can fatigue the living hell out of your lower back, even with perfect form. This is especially true if you’re continuing to Deadlift, Low Bar Squat, etc with regularity. The same is true with Barbell Rows, especially with how I coach them, which involves not resetting the bar on the ground each rep. Instead I prefer the bodybuilding style row where the torso is kept closer to 45 degrees and the lumbar muscles must be able to hold a fairly long isometric contraction while the lifter rows a heavy barbell – usually for sets of 8-10 reps on average. Now, if you do them right and you set up correctly, there shouldn’t be THAT much stress on the lower back, but this is an exercise where most people struggle with the set up, especially when just learning. So sometimes we have to really account for low back fatigue when doing heavy barbell rowing. Now in the long run, I think it’s worth it to learn the row because over time it will absolutely blow up your back with more size. And as it actually starts to get heavy you can see and feel it start to have some impact on the deadlift. But incorporating all of these things into the weekly training plan can be a bit much over time – Squat, Deadlifts, Stiff Leg Deadlifts, and Barbell Rows are all taking a toll on the lower back. And for any of you who have really felt the effects of beating the shit out of your low back for too long you know it can take a while to get yourself recovered and in the meantime your lifts can really suffer. So here is one of the strategies I’ve been using lately with many of my clients to keep them progressing and feeling fresh. It should be noted that this strategy is one that I might use for a client who is generally consolidating all of his/her high stress deadlifts and deadlift accessories to just one time per week. You might do some light deadlifts later in the week after you squat heavy, but in general this protocol is not ideal if you’re a trainee who likes to deadlift with a lot of frequency. This method is stupidly simple but I like the results I’m seeing from my clients. The Method…… For the first 3 weeks, we focus on building up to a peak in the Stiff Leg Deadlift. Starting with lower intensity and relatively high volume we do a simple wave that looks like this: Week 1: 3 x 8-10 (straight sets) Week 2: 3 x 6 (add 5-10% from week 1 and drop the reps to 6) Week 3: 1 x 4-8 (add 5-10% from week 2 and go for an all out maximum set). Sometimes I follow this with a lighter back off set of 8-12 reps, sometimes not. During this 3 week wave, we don’t do any Barbell Rows. We still row, but we select from other rowing variations. We might do a different one each week or stay with one variation for the whole 3 week wave. The only two rules that apply are (1) the variation you choose doesn’t beat up the lower back (2) you are able to establish a good mind muscle connection with the variation you choose. Good options are chest supported t-bars, chest supported seated row machines (there are dozens of models), cable rows, and even dumbbell rows. Reps are generally in the 8-12 range. We do these rows after the Stiff Leg Deadlifts. So our workouts for the first cycle might look like this: Week 1 – 3 Light Squat 3 x 8 Heavy Deadlift 3 x 8 / 3 x 5 / 3 x 2 Stiff Leg Deadlift 3 x 8-10 / 3 x 6 / 1 x 4 – 8 Chest Supported Row or Dumbbell Row 3 x 8-12 Lat Pulldowns 3 x 10-12 After 3 weeks we drop the Stiff Leg Deadlifts, and substitute them with the Barbell Row for another 3 week wave. With the rows I don’t have an exact set and rep scheme that I use for everyone. Some people are really good at heavy barbell rows and some are not so there is plenty of room here for individual variability, but in general we follow a pattern of starting lighter with higher reps and tapering down to heavier with less reps. That might mean starting at sets of 12, down to sets of 10 in week 2, and down to sets of 8 in week 3. Or you might start with sets of 10 and taper down to sets of 6 in week 3. But honestly……don’t stress about this too much. Actually, don’t stress about this at all. Programming barbell rows is not nearly as hard as doing them correctly. The main thing is that you are doing a whole bunch of quality reps and the weight is slowly going up over time. Keep the reps between 6-12 and keep driving the weight up and perfecting your form and you’ll be good. That’s it. At the end of today’s Deadlift workout, we’re going to still hit some work on the lower back and hamstrings, but we’re going to use movements that are far lower stress than a stiff leg deadlift. Our main goal here is to keep these muscles conditioned to lots of work, so that when we go back to the Stiff Legs in 3 weeks we haven’t lost all our conditioning to them. My 3 favorites are 45 degree back extension, 90 degree back extensions, and reverse hypers. So Week’s 4-6: Light Squat 3 x 8 Heavy Deadlift 3 x 8 / 3 x 5 / 3 x 2 Barbell Rows 3 x 10 / 3 x 8 / 3 x 6 Lat Pulldowns 3 x 10-12 45 Degree Back Extension 3 x 15 After Week 6 we simply start back over with the cycle we ran in weeks’ 1-3, dropping the BB Rows and getting back into the Stiff Legs. Every time you start a new cycle, look back at your training log and see what you did last time and try to beat your performances. So if in the first cycle (weeks 1-3) you did this: Week 1: SLDL 3 x 8-10 x 315 Week 2: SLDL 3 x 6 x 330 Week 3: SLDL 350 x 7 (rep max) In the next cycle (weeks 7-9) you would do something like this: Week 7: SLDL 3 x 8-10 x 325 Week 8: SLDL 3 x 6 x 340 Week 9: SLDL 355 x 7 (rep max) We would do the same thing with the Barbell Rows. In the first cycle with your Barbell Rows (weeks 4-6) you might do this: Week 4: Barbell Row 3 x 10 x 185 Week 5: Barbell Row 3 x 8 x 205 Week 6: Barbell Row 3 x 6 x 225 Then we’d drop the BB Rows for 3 weeks, cycle back to SLDLs but in weeks’ 10, 11, 12 we’d cycle back to rows like this: Week 10: Barbell Row 3 x 10 x 195 Week 11: Barbell Row 3 x 8 x 215 Week 12: Barbell Row 3 x 6 x 235 If your Deadlift is not where you want it to be you might consider something like this. Bouncing back and forth in these 3 week mini cycles for about 6 months or so should take your Deadlift PRs to a whole new level. Bench Press Blow Up Your Bench Press (3 Easy Tips) How much ya Bench? Chances are if you’ve spent more than about 5 minutes in the gym you have either (1) asked this question or (2) been asked this question. Hopefully you are in the latter and not the former. It’s just better that way. The latter is a gesture towards the fact that you’ve probably accomplished something in the gym and at the very least – you look like you lift. The former is the true sign of a gym noob (almost as bad as facing the plates outboard on the barbell) – but probably something that we were all guilty of doing at least once in our gym life. If you are currently the guy that walks around the gym (or worse – at the party) and asks everybody “How much ya Bench?” – please stop. That being said, being able to Bench a lot of weight is still a productive thing to be able to do. It builds tons of muscle in the upper body, helps to build a bigger Overhead Press, and most importantly it gives you a good answer to the annoying kid in the gym who is eventually going to ask you how much you Bench. (Hint: In reality the best answer to that question is “I don’t Bench” or “I don’t workout” – even if you do. This is especially true if you Bench over 315. A 315+ Bench immediately invites a discussion on how you benched 315 – and this should be strictly avoided, especially in social settings, and especially if you are trying to get laid). So let’s look at a few strategies that might help you improve your Bench Press….. #1: Prioritize The Bench Press For many of you reading this you will have used novice and intermediate programming up to this point that pretty much had equal focus on the Bench and the Press. I’m okay with that, but the Bench Press likes frequency and volume, and to really get it to move, it might need enough work that you simply won’t have time, energy, or recuperative capacity to put equal focus on the Bench and the Press. For a 3-day per week plan (Mon-Wed-Fri) I’d suggest Benching on Monday and Friday and Pressing on Wednesday. For a 4-day per week plan (my preference if Benching is a high priority for you) I’d suggest a Heavy Bench Day and Press Day, and I’d follow each of those movements up with supplemental variations of the Bench Press for increased overall volume and to work weak points. Something like: Monday Bench Press Close Grip Bench Thursday Press 3 Count Paused Bench Press #2: Always Use Close Grip Bench Presses Assistance exercises are not always reliable predictors of success on their parent lifts. But in my opinion – nothing is as reliable an indicator as a Close Grip Bench Press is to a Bench Press. Almost without fail when I can get progress for a client on their close grips – the Bench Press will move too. A close second might be the carryover of a Stiff Leg Deadlift to a Deadlift, but I still think Close Grips win out. I’d suggest including them either as back off work to the regular Bench Press, or on a second day of the week – perhaps after Presses or as the main exercise of the day. Doesn’t really matter – just do them if Bench Presses are a priority for you. I would do a minimum of 3 sets, and perhaps as many as 6 sets mostly in the 5-8 rep range. You can occasionally take them heavier – for heavy 5RMs, heavy triples across, or even heavy singles, but Close Grips work best as a “builder” of strength rather than a tester of strength so I’m a fan of more volume on Close Grips. #3: Use Lying Tricep Extensions To Build the Close Grip Bench Press As the Close Grip Bench builds the Bench, the LTE will build the Close Grip. Close Grips for volume will always die out due to localized muscular fatigue in the triceps. Close Grips are notorious for dying out 2-3 reps short of when you think they are going to die out. The triceps just love to shut off unexpectedly and when they are done…they are done. If you are going to build up to big volume on the Close Grip Bench Press as a means to build your Bench, then you better due something about the work capacity of your triceps outside of just Close Gripping. My suggestion is that every time you train the Bench Press, the Press, or a variation thereof, you also train the triceps directly. LTEs are good, but so are Overhead Extensions/French Presses and Cable Pressdowns. I suggest you do these for reps in the 1015 range for about 5 sets. Train your triceps to handle high volumes on short rest intervals (1-2 minutes) and your Close Grips will respond and in turn so will your Benches. In Practice…… Here is a look at how we’ve programmed the last several months of the Baker Barbell Club Online – and my guys have been setting Bench Press PRs left and right (see video below). Bench Day (every 4th workout) Bench Press 3 x 8 / 3 x 5 / 3 x 2 – rotate rep ranges each week. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume and aim for a conservative PR for each rep range each time it comes around. Bench Supplemental (exercise varies each cycle) or Light Press 3-5 x 5-8 Bicep Curls Dips 3-5 x max reps *Biceps after exercise #2 allows for some rest/recovery of the chest/delts/triceps before we do our Dips so we can hit better numbers of reps or use loads on the Dips. Press Day (every 4th workout) Press 3 x 8 / 3 x 5 / 3 x 2 – rotate rep ranges each week. Rest as needed between sets to complete the volume and aim for a conservative PR for each rep range each time it comes around. Press Back Offs – 2-3 x 8-12 Side Delts / Rear Delts Close Grip Bench Press or Floor Press 5 x 5-8 Tricep Extensions (1-2 exercises) 3-6 x 8-15 *Side Delt/Rear Delt work after the Press Back Offs allows us to hit better numbers on the Close Grips than if we do the Close Grips immediately after our Press Back Off work as the triceps are allowed more time to rest and recover from the fatigue of higher rep Pressing. Even though the Baker Barbell Club Online Programming is a general power-building program, not specifically focused on prioritizing the Bench Press, you can see how the concepts work in practice. Bringing Up Your Bench Press (Frequency, Intensity, Volume, Exercise Selection) Yes, yes, I know another “How to Bench Press More!” article. Add it to the thousands already floating around the internet in 2019 – some beneficial, many more are simply click bait. Hoping you’ll find this article leans towards the former! This particular “check list” of to-do’s is not necessarily meant to be the Final Word on Bench Press programming. But, as I often do, I tend to write about topics and practices that I’m currently having success with whether it be personally – or more often – in the role of a coach working with my clients at the gym or online. Frequency It’s currently in vogue to Bench Press with a pretty high frequency, often 3 days per week, or even as many as 4 days per week. Obviously this can work as many lifters are finding success with the high frequency approach. The main drawback to this approach is you really need to be able to dial in your per session volumes and intensities as the margins for error decrease as frequency goes up. I don’t program this way as a coach or a lifter so I can’t really advise beyond that. I personally have found my best results from a twice per week frequency on the Bench Press. In 2010 my best Bench Pressing came from a simple twice weekly program using a 4-day Texas Method type split. The first session of the week was a simple 5 x 5 volume approach. I generally followed the 5×5 Benching with 3-5 sets of 8-12 reps of Weighted Dips. Later in the week I would Bench for 5 singles across. I alternated the singles workouts between regular Paused Bench Presses and Dead-Stop Rack Bench Presses – each rep starting from the bottom from a Dead Stop. I followed this up with a high volume of strict shoulder presses and lots of tricep work. The end result was a 380-lb strict paused bench at a body weight of 192 lbs. Nothing elite by any stretch, but it was a N.A.S.A. state record for a few weeks I think! A few weeks later I hit 405 in the now defunct Asylum Gym when my body weight crept back up to about 210215. Sadly – that was my one and only 405 Bench Press! But since then I’ve been able to maintain a consistent ability to hit around 385 on the bench with a variety of different types of programming, benching just 1-2 days per week. I’m a fan of hitting a fairly high volume of assistance work to compliment your Bench Press training and that is another reason I like just training your Bench two times per week. Most assistance work needs to be taken to, or at least very close to, failure for multiple sets in order to induce the hypertrophy response we want from it. If you are taking lots of sets to failure you will have to reduce frequency to 1-2 times per week in most instances. If you think you’ll respond better to benching 3-4 times per week, my suggestion is to severely limit the number of sets you take to failure on any major compound exercises or higher stress assistance work. Cycling Intensity Every Week The program I outlined above is not really a sustainable long term program although I would still recommend it to certain lifters for a short period of time prior to a testing date or meet. Pushing the heavy 5x5s combined with singles across is a really powerful stimulus, but it will run it’s course pretty quickly. The one thing I do like about the above approach however is alteration at each training session between volume and intensity. I think most lifters do best when they feel something heavy in their hands once per week. However, the nature of “heavy” can change on a weekly basis. In fact, I’d argue it SHOULD change on a weekly basis. It’s a rare thing indeed to find me programming anything anymore that is not cyclical in nature. For a more basic intermediate program, like the one we just got done running in my online coaching group with the Garage Gym Group, we cycled each heavy bench press session between a heavy triple, double, or single. This works good for less experienced lifters, lifters who have limited equipment access, and lifters who simply prefer simple and basic. Combining this approach with a volume session on an alternate day of the week, we had a lot of PRs each week. If I’m not cycling rep ranges for an exercise then I tend to cycle exercises. This is the basis of the conjugate method popularized by Westside Barbell and Louie Simmons, but now used in many, many strength programs around the world. This is the system we are currently running in my online coaching group with the Power Building Group. What I generally do here is work through a rotation of maybe 6 Bench Press variations, and each time we have a heavy Bench Press session, we take one of the variations up to a 1-rep max for the day and then follow with a few back off sets. You can also work in variations of the Press if you want to split focus between benching and overhead pressing. What I generally recommend is something like this if you are focused on the Bench Press: 1. Competition Bench Press – alternate between touch n go & paused 2. Change Angle – Incline or Decline (I hate declines, but you can use them if you want). Inclines are good between 30-60 degrees 3. Change Grip – use a close grip bench press with index fingers 16″ apart 4. Perform a partial – floor press, pin press, 1-2 board press, etc 5. Use a specialty bar – cambered bar, football bar, axle bar, buffalo bar, etc 6. Use accommodating resistance – bands or chains So that is a 6 week rotation, but honestly if you used all the permutations available for each ‘category’ you have an almost infinite amount of variations you can use. The point of the Max Effort session is basically to strain hard against a heavy weight for a few heavy singles at or above 90%. You want to try and set a new PR if possible on a given variation, but it isn’t necessarily a requirement each week. By switching exercises we assure we don’t burn out and can condition the body to go heavy every week. Which ever form of cycling you prefer…..go heavy. Go heavy often. But don’t repeat the same sets / reps / weight / exercise every week. Two Weekly Volume Sessions The volume work on the Bench Press or it’s close variations is performed twice per week for most clients, but the nature of each volume session is different. After the max effort exercise singles I like to perform some back off sets of that variation for about 10-20 total reps in the 75-85% range. So this is our heavier volume work. Later in the week I like a lighter volume session focused on speed, often with the use of light mini bands. Speed work is done with about 40-60% of bar weight plus the addition of light bands. If no bands are used then we might up the percentages to 60-75% with straight weight. I find this is optimal bar speed for most lifters. The weight needs to move fast. But you should have to work to make it move fast. Speed work is done with 6-12 sets of 2-3 reps on about a 60-90 second rest, although we’ve done up to 15-16 sets and recovered fine. Many lifters get faster as they go between each set and in that case we may add sets to take advantage of the speed increases. Having two different types of volume sessions in our week allows us to train volume HARD twice per week without overtraining. Adding Assistance The Bench Press responds well to the addition of assistance exercises. On your heavy Bench Press session – pick an exercise to blast the pecs and go to town with 3-5 sets with reps in the 8-15 range. I like a mix of Dumbbell Bench Presses, Incline Dumbbell Bench Presses, Decline Dumbbell Bench Presses (I only hate the barbell version!), and Dips (pick one exercise per session – not all in same session). After you hit the chest, follow up some work for the lats and rear delts. Having a bigger back helps tremendously on the Bench Press. On your Speed Bench Day, follow up with a high volume of work for the delts and triceps. Do a bunch of barbell or dumbbell presses, and 1-2 tricep extension movements: lying tricep extensions with dumbbells or barbells, overhead tricep extensions with barbell or dumbbells, cable pressdowns, or more dips, etc, etc. Of course there is 101 ways to arrange assistance work so do whatever suits you best. But don’t avoid it if your Bench Press is stuck. Example Week Monday – Intensity Bench Press 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Option 1: Bench Press – rotate between heavy triples, doubles, or singles Option 2: Bench Press Variation – work up to heavy single Back Off Sets: 3 to 5 sets of 3 to 5 reps @ 75-85% DB Chest Press or Dips: 3 to 5 sets of 8-15 Chest Supported Rows 5 x 8-15 Face Pulls or Rear Delt Raises 3 x 15 Thursday – Volume Bench Press 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Speed Bench Press: 8-12 sets of 2-3 reps @ 40-60% + Mini-Bands Barbell or Dumbbell Shoulder Press 5 x 8 Lat Pulldowns 5 x 10-15 Tricep Extension 1: 3-5 x 8-12 Tricep Extension 2: 2-3 x 12-20 Bench Press Technique There are two different bench techniques for (1) moving the most weight (2) building the chest. When you do a Bench Press session you need to decide what the purpose of that session is. It might vary from time to time. When competing....the Bench Press is a LIFT, not an EXERCISE. The objective is to move the most weight from point A to point B and typically this means we will manipulate the leverage in whatever way is necessary to do that, even if it comes at the expense of training certain muscle groups - think big arch, wide grip, low touch point (tip of the sternum or even upper abs). If we want to build the triceps we are going to narrow the grip substantially - sacrificing load for stress on the triceps by creating a very acute angle at the elbow. If we want to stress the pectorals we are typically going to use a more moderate arch, a medium-ish grip and most importantly....a higher touch point typically at the bottom of the chest or even right in the middle of the chest. And the elbows will be flared more to the sides vs tucked. Why? Think about the function of the pecs adduction of the humerus. Think of a Chest Fly. That is the function of the chest. With the higher touch point and elbows out we are using the chest to bring the arm from an abducted position (away from the body) towards the body (adduction). When we do this, we sacrifice some load. If you are training for maximum bench press numbers you need to do your max effort work and your speed work in the strongest position. When you are trying to build the pecs - change the mechanics a bit. Typically I'll do the higher rep back offs in the "bodybuilder" style in order to build the pecs. This is also the reason why I (and others) like to use a lot of Dumbbell work because dumbbells enhance the adductive (I don't think that is an actual word) function of the chest by allowing you to focus more on getting the humerus OUT (abduction) and then bringing the humerus IN (adduction). Flys completely isolate this function without contribution from the triceps.....but you make a huge tradeoff in LOADING when you do flys instead of presses. This all runs in parallel with how we might train for a bigger Squat vs training for bigger quads. Bigger squats typically come from a wider stance and a low bar carry. More weight, but potentially not the best way to build a jacked set of quads which might be better trained with a closer stance, a deeper range of motion (ass to grass even), and a high bar carry. Less weight but more tension on the quads. And Leg Extensions are even more isolated on the quads removing any contribution from the hams, glutes, and adductors, but again...like the flys.....a massive trade-off in loading. So to bring this back to your original question......I think you can potentially have TWO different touching points based on what the objective of the workout is. If you want to train the LIFT.....touch low and use max weight and focus on movin the weight from point A to point B. If you want to train the Pecs.....touch higher and use less weight and focus on the mind muscle connection with the pecs. Press How to Build a Bigger Overhead Press (7-step Blueprint) Everyone wants a bigger Overhead Press. Of course we all want a bigger Squat, Deadlift, and Bench Press too. But there just seems to be something uniquely cool about standing out in the middle of the floor – just you and the barbell – and pressing it over your head. I remember Mark Rippetoe once saying at a Starting Strength seminar a number of years ago that the first thing the cavemen did when they found the first set of barbells was pick it up and shove it over their heads. It just seems like something you should do if you want to get strong. For starters, there just aren’t a lot of guys with big overhead presses. It seems like nowadays 500-600 lb Deadlifts are a dime-a-dozen, but you still don’t walk into most commercial gyms and see anyone repping out 225 overhead on a strict overhead press. So let’s figure out how to do that, so you can be that guy. Big Press Rule #1: Don’t lose bodyweight More so than any other lift, the overhead press is extremely sensitive to changes in your bodyweight. Five to ten pounds of weight gained or lost can affect your progress on the press significantly. When we lose weight, we lose some combination of fat, water, and muscle mass. How much of each depends on the individual and their nutritional plan. A proper nutrition plan can help to minimize muscle loss, but if you try to cut significant amounts of weight you are probably going to lose a little bit of muscle unless you are using anabolics (I am life time drug free as are my clients). But mainly (on top of the fat that you want to lose) you are going to lose quite a bit of water in and around the muscle cells. A loss of water weight changes leverages around your joints – usually to your detriment when it comes to strength. This is why many power lifters aim for “The Bloat” prior to a contest. A single (or several) high sodium / high carbohydrate meals can add several pounds of water weight to a lifter in a short period of time. This extra water weight stored in and around the muscle cells creates better leverage around all the joints and will increase your lifts. (Great “bloat” meals include things like McDonalds French Fries or an order of Pancakes and Sausage – remember high carb + high sodium combo). The more muscle mass you have in a lift (think Squat or Deads) the less a small loss of water weight is going to affect you. But in a Press we aren’t using very much muscle mass to move the barbell (delts and triceps). Even small changes in leverage are very difficult to overcome when you don’t have a lot of muscle mass to make up for it. Sooooo……if you want to prioritize your Press, don’t try and prioritize weight loss at the same time. Pick which goal is more important to you and get that done first. Big Press Rule #2: Train the Press with Lots of Strength Volume Presses like strength volume. You may be asking – what the hell is strength volume? Strength volume is a term I made up (I think) that differentiates between different types of high volume training. To me “strength volume” is work done in the 75-85% of 1RM range, generally with a rep range between 3 and 6 and a set count usually between 4 and 6. So set/rep schemes such as 5×5, 4×6, 6×4, or even 8×3. This is “strength volume” training and Presses seem to respond very well to it. The other barbell lifts do too, obviously, but Presses are particularly dependent on this type of volume work. Be sure to include a strength volume day at least once per week if you want to prioritize Pressing (recommended 18-24 total reps between 75-85% of 1RM). Big Press Rule #3: Train with Higher Reps (8-12) Too Although the meat and potatoes volume work should be “strength volume”, Presses also like a little bit of dosing in the higher rep ranges as well. You don’t need to dedicate an entire training session to higher rep training, but I recommend the occasional back off set or two in the 8-12 rep range. You can do these back off sets after your strength volume work or after higher intensity sessions. It really doesn’t matter, but once a week or once every two weeks I’d aim for a max effort set(s) between 8-12. This type of training will do a couple of things for you. First, it helps with size. As we discussed earlier, the delts and triceps are the primary movers in a Press and neither muscle is particularly large when we compare them to quads, glutes, hamstrings, etc that we use in the Squat and Deadlift. Even a small increase in muscular size (even if it’s mainly just swelling of the sarcoplasm) will help to improve leverage for the heavier lifts. Second, it will increase your endurance and work capacity on your “strength volume” work. Doing very heavy 5×5 sets is not easy. Often the limiting factor on your later sets is muscular endurance. You simply gas out early and can’t perform all your sets at the prescribed loads. Or you have to take 10 minutes between all your sets and it takes you an hour just to press. Also not ideal. Triceps especially tend to gas out rather quickly and training some high rep presses relatively frequently will keep them in the game longer. Big Press Rule #4: Train Frequently with Heavy Singles As discussed, volume work is exceedingly important for driving up your Press. But if you want to Press heavy – eventually you have to press heavy. You need to learn how to grind through a very heavy load, you need to learn where you sticking points are, and you need to train your nervous system to handle heavy loads. Singles across is my favorite method of heavy press work. And I like lots of heavy singles across. Generally a minimum of 5-6 and often times up to 10 heavy singles across. Often times you will find that as you perform your singles across workout, the first 3-4 sets are very difficult and then all of a sudden things get easier and you can crank out a ton of singles with a nice smooth bar path. If I notice this start to happen we’ll do up to 8-10 sets of singles. If not, then we usually cut things off at 56 as to not overtrain the CNS. Heavy doubles and heavy triples are fine as well, but I’d make the vast majority of my high intensity press sessions “singles across”. Singles on one day and fives on another day go together like steak and potato. The best combo for strength in my opinion. Big Press Rule #5: Use Dynamic Effort Sets (Speed Work) to Bust Plateaus. All lifts eventually get stuck and we need to have tools in our tool belt to unstick them. I don’t use Dynamic Effort Presses year round with all my trainees, but I do use them for short blocks of time to get a stuck press unstuck. Usually I start by adding in Dynamic Effort sets in place of the high intensity day for about 4-6 weeks. So if we were doing 5×5 on Monday and 5×1 on Friday, now we do 5×5 on Monday and 12×2 on Friday. I find that for Presses, the optimal bar weight is about 60-70% of 1RM. I like to do a “pyramid” type of workout with Dynamic Effort sets. As an example: Lifter with a 225 lb Press: Set 1-2: 2 x 135 (60%) Set 3-4: 2 x 145 (~65%) Set 5-8: 2 x 155 (~70%) Set 9-10: 2 x 145 (65%) Set 11-12: 2 x 135 (60%) Rest time between sets is kept to about 1 minute and emphasis is on max bar speed. This is a new type of stress for the system which has become used to slow grinding reps on both volume and intensity days. On multiple occasions I have seen the speed stimulus get a lift moving again after just 1-2 workouts. After 4-6 weeks go back to the use or regular strength volume work and high intensity work or use the speed sets on your volume day and press heavy singles across on the other pressing day of the week. Big Press Rule #6: Train the Incline Bench Press and/or the Close Grip Bench Press If you want a big overhead press you need to keep bench pressing as well. Bench Presses allow our upper body to handle significantly heavier poundages than does the overhead press and this is important for the development of the overhead press. If you want to press 275 overhead one day – you probably need to bench it first. However, don’t forget about the incline bench press and the close grip bench press. Both of these lifts still allow us to use heavier-than-press weights, but they also are a little more specific to the press than is the regular bench press. Close grips obviously allow you to overload the triceps and press very heavy weights with a “press grip” – or at least somewhat close to a press grip. Inclines work the upper chest and front delts much more so than does the flat bench press. A very heavy press with a lot of layback sometimes winds up looking like a standing incline press – even if only by accident. The point being that the angle of the incline is quite beneficial for training the musculature used in the press. The incline bench press is particularly useful if you are weak out of the bottom of the press (something you won’t know unless you frequently press singles by the way). Several years ago when I pressed 285, I had been stuck at 265 for quite some time. My press didn’t move until my incline press moved. When I moved my best incline from 295×3 to 315×3, all of a sudden I pressed 285 with relative ease. The focus on the incline was the only major factor I changed in my programming. Big Press Rule #7: Train the Triceps The best exercise for the Press is the Press. There aren’t a whole lot of Press-variations that I have found to be useful as assistance exercises (other than the bench press and its variants). The best assistance exercises for the Press are those that train the triceps – particularly the long head of the triceps on the inside part of your arm. While you can’t “isolate” a particular head of the tricep, you can and should emphasize a particular area of the tricep. Which head of the tricep is most active in an exercise largely depends on the position of the shoulder during the exercise. Maximal shoulder extension would be on an exercise like Dips or Tricep Kickbacks. Kickbacks are totally worthless so throw those out, but Dips are useful for triceps training, although their focus is mainly on the outer head of the tricep, or what Louie Simmons likes to call “the lazy head.” I love dips and I recommend that you do them because of the total amount of overload they place onto the totality of the triceps, but don’t just rely on Dips. The long head / inner head is best trained by movements where the shoulder is in full flexion (i.e. extended overhead). French presses with an ez-curl bar or a dumbbell (unilateral is best) are the best exercises for the long head of the triceps. Lying triceps extensions and rolling dumbbell extensions are also good builders of the long head. Do a mix of tricep exercises 1-2 days per week for 3-6 sets per exercise in a rep range between 6-12. Occasionally do some very heavy dips or lying tricep extensions in the 4-6 rep range, but don’t abuse your triceps with too much frequency on the heavy stuff. Your elbows won’t hold up to too much isolation type work dropping below about 6 reps. A Simple 6-week Overhead Press Program (Get Unstuck!) This is a program I’ve been using with clients for a number of years, but haven’t written much about it. So I figured it’s about time to share. I generally implement this simple protocol when a trainee is having a tough time getting their Press to do move forward in a meaningful way with more basic programming. The program essentially uses two different strategies that most trainees (up until this point) will have been unfamiliar with. I hate using this term, but the program serves as a pretty good “shock” to the system, as well as an increase in volume to what they may be accustomed to. I first used this program on myself about 4-5 years ago when my Press was stuck at 250 lbs and I couldn’t get it to budge. After the first 6-week run on the program my 1rm jumped to 265 lbs. I tried running the protocol again for another 6-weeks but had less success with it. Since that time I have used this program with clients maybe 15-20 times over the years and each time I’ve had really good success getting a Press “un-stuck” in about 6 weeks time frame. A handful of times, I’ve used this for 12-18 week runs of progress, but most of the time I wind up altering the program back to something more basic after 6 weeks with a program based off of the new 1RM. On this program, the frequency is usually 2 days per week (Monday and Friday). If you want to add in a 3rd light press day on Wednesday, you can, but I usually perform Bench Presses on Wednesday. And this program works just fine on a 2x/week frequency, so I don’t think you need to Press 3x/week unless you just don’t like to Bench Press. On Monday, we’ll perform a pretty simple 5×5 workout. I suppose you could use something else that is largely equivalent (4×6, 6×4, etc) but I usually just stick with what I know works which is 5×5. The idea is to get 6-weeks of progress using 5×5, so start with a weight that allows you to get all 25 reps in good clean form. Something around 70% of 1RM is a good starting place. Each week you can go up in weight about 2% which after 6 weeks will bring you to about 80% of 1RM. This will be very challenging but doable. Example Monday: Week 1: 5x5x70% Week 2: 5x5x72% Week 3: 5x5x74% Week 4: 5x5x76% Week 5: 5x5x78% Week 6: 5x5x80% Week 7: 3x3x80% (deload) You don’t have to use %’s, but this is just there to give you an idea on how to load. You need to keep the load in a place that is challenging, but where you aren’t down to doubles and triples by week 6. You should be able to get 5×5 for 6 weeks, unless you start way too heavy. However, if form gets shitty or you just can’t muster a 5th rep, then you can alter the scheme to like 6 x 4. You should be able to get at least 4 reps per set unless, like I said you start way too heavy in week 1. If you know your Press 1RM, then 70% should work pretty universally as a starting point. If you mess things up and start way too heavy in week 1, then simply lower the weight on the barbell, recalibrate your loads and aim for 5×5 each week. On Friday you will alternate between Dynamic Effort Sets and High Volume Heavy Singles Across. I use 10 sets on each day, although on the Dynamic Effort Days I’ve gone as high as 12-15 sets if the weight is flying up. Week’s 1, 3, 5 will use Heavy Singles Across. Week’s 2, 4, 6, will use Dynamic Effort. This will set you up best for a testing week in Week 7. The Friday Workout will look like this: Week 1: 10 x 1 x 90% Week 2: 10 x 3 x 60% Week 3: 10 x 1 x 92-93% Week 4: 10 x 3 x 62.5% Week 5: 10 x 1 x 94-96% Week 6: 10 x 3 x 65% Week 7: Test New 1RM A few notes and observations……. 1. The heavy singles across workouts start moderately hard (sets 1-4), they get really hard in the middle (sets 4-7) and then it’s almost always reported that sets 8, 9, 10 felt lighter and faster. I’ve seen this happen with my in gym clients on multiple occasions and this was also my own personal experience with this program. This is a good sign that the program will pay dividends. Even in Week 5, you’re going to think “How in the bloody hell am I going to get 10 sets of this??” But you will. Just keep knocking them out and you may be surprised that set 10 @ 95% moves pretty well. 2. If you miss a weight for some reason, back the weight down slightly and continue until you get all 10 singles. Try and keep rest down to 1-2 minutes in weeks 1 and 3 and then expand that rest time out a bit to 2-3 minutes in week 5 as needed. Make sure you wear a belt and wrist wraps. This can take a toll on the joints. 3. On Dynamic Effort Days you must move the barbell as quickly as possible. 10x3x60% is not much of a stimulus unless you move the load with speed. Each rep should be moved on the concentric as fast as possible, with a controlled eccentric. Some coaches teach to move the entire rep (eccentric and concentric) as fast as possible, but I don’t like that technique on the Press. It gets sloppy if the eccentric is not controlled. Focus your speed on the concentric. 4. Rest about 60-90 seconds between sets on the Dynamic Effort Days Assistance Exercises Improving Your Pull-Ups or Chin-Ups: Do’s and Don’ts One of the most frustrating exercises to make improvements on for many trainees is the Pull-Up and the Chin-Up. We often use the terminology for these two exercises interchangeably, but I guess there is some level of nominal agreement within the strength training world that Pull-Ups are done with an overhand grip (palms facing away from you) and Chin-Ups are performed with an underhand grip (palms facing towards you). In the end it’s not terribly important which exercise you prefer, both exercises work the lats pretty thoroughly, but Chins give quite a bit more work to the biceps, which is why trainees can generally get more reps in this fashion. I’ve tried basically every method you can think of over the last 10+ years with different trainees to see what works best and what doesn’t work at all. Below are my thoughts and observations about what works and what doesn’t when it comes to improving chin up / pull up performance. #1: Aim to Improve Chin Ups first…..Pull Ups Will Follow. As Chins are easier to improve (which might mean getting from 0-1), get these strong first and your pull-up strength will eventually follow. Work your Chins hard until you can get about 8 of them and then start adding in Pull-Ups. At first, you’ll probably get about half the number of Pull Ups as you can Chin Ups, but they’ll improve fast. As you start improving your Pull Ups then you’ll start getting better at Chin Ups too. The two exercises will kind of wind up feeding each other. #2: Don’t Waste Your Time With Negatives Pretty much summarizes my thoughts on this methodology. Never had much luck with it. #3: Use an Assist – But Do It Manually First I’ll tell you that the “Gravitron” or Assisted Pull-Up Machine is a waste. In the several years I spent working at various Globo Gyms that had this piece of equipment I don’t think I ever once successfully moved someone off of this machine and into a real chin up or pull up. Resistance Bands are slightly better but not by much. The problem with using a machine or bands as an aid to get you up over the bar is that there is continual assistance through the entire movement. This is actually a bad thing. There will be parts of the pull up / chin up where you are able to complete some of the range of motion on your own, but these apparatus don’t allow you to do any of the work yourself. They give you aid even when you don’t need it. Also, sometimes you may be able to get 1-3 reps or so on your own but then you peter out and need assistance to complete more volume. These apparatus support you through an entire set, even when you don’t need it. The better option is Partner Assisted Pull Ups with Forced Reps. This is admittedly hard to do if you train alone. But, as long as you instruct him or her correctly, your partner can cup your feet in their hands or place their hands on the small of your back, and give you assistance only where you need it. For instance, you may be able to get from a deadhang to about halfway up with your own strength and then get stuck in the middle of the rep, this is where your partner can give you a slight push to get you through that sticking point to allow you to finish the entire rep. Or maybe it’s the inverse. You can’t get your fat ass moving from a deadhang, but once you get about halfway up you can complete a rep. Your partner can give you a little bit of a boost out of the bottom of the rep and then ease back on the amount of help they provide and let you finish the rep on your own. For this to work, your partner should keep his hands on your feet or the small of your back for the entire rep, but only aid when he feels you start to stick. Additionally, I like to do a couple of forced reps at the end of each set with partner assistance. So crank out as many as you can on your own and then have your partner help you with 2 to 3 additional reps with a spot. This has been my most reliable method of increasing a trainees pull ups / chin ups over the years. #4: No Partial Range of Motion – Learn to Pull From Your Lats Many trainees who are weak on Pull Ups / Chin Ups like to shorten the range of motion and only go about halfway down each rep. This forces you to use mainly biceps and forearms to complete the movement. You’ll actually be stronger if you allow yourself to descend ALL the way down, feel your Lats stretch at the bottom of the movement and rebound out of the hole with your Lats. The Lats are obviously much bigger and stronger than the Biceps/Forearms so harness the power of the stretch reflex from the lats and learn to go all the way down, stretch, and EXPLODE out of the bottom with the power of your lats and then finish with your arms. #5: Get The Grip Right I see most people go too narrow on both exercises. Too narrow on Chins makes for a very long range of motion and a heavy dependency on the Biceps. Go about shoulder width or a just a tiny margin wider on Chins. Pull Ups should be done a good distance outside of shoulder width at first. A shoulder width or narrower grip on a Pull Up is very mechanically dependent on the strength of the forearms which is the weakest link in your chain. Go wider to shorten the range of motion a bit and get more into the lats. #6: Use Lat Pulldowns to Build Volume and Muscular Endurance In combination with regular Pull Up or Chin Up work, adding higher rep Lat Pulls to the mix is beneficial. This has the benefit of allowing you to do some “density work” for the muscles involved in the Pull Up / Chin Up and use the incremental loading ability of the Lat Pull machine to slowly build strength. Usually I set up two workouts per week dedicated to improving Chin Ups / Pull Ups if this is something you want to focus on. The first workout would be Chin Ups followed by Lat Pulls with a wider overhand grip. The second workout of the week would be Pull Ups followed by Lat Pulls with a narrower underhand grip. If you are weak on both exercises, aim for about 20-25 total reps of Chin Ups / Pull Ups each workout in as many sets as it takes to achieve that number. As a measure of progress look at the total number of reps you achieve on your first work set, as well as how many total sets it takes you to achieve each rep total goal. Over time, we want the number of reps you perform on set #1 to increase and the total number of sets you perform to reach your target number to decrease. When you can achieve your target number in 3 sets then bump up your total by 5-10 reps. Follow this up with 3-5 sets of Lat Pulls in the 8-10 range with short rest periods, full range of motion, and absolutely perfect form. #7: Train Your Biceps Tack these onto the end of your Chin Up / Pull Up / Lat Pull workout. I like the following set up: Day 1: Chin Ups (20-25 total reps), Wide Grip Lat Pull 5 x 8-10, Barbell Curl 3 x 8-10 Day 2: Pull Ups (20-25 total reps), Reverse Grip Lat Pull 5 x 8-10, Hammer Curl 3 x 810 If you want to really prioritize your Chin Up / Pull Up strength it’s going to mean making some room in your weekly training split to give enough attention to the movements. If you suck at them you cannot just throw a couple of sets onto the end of a Squat, Bench, Deadlift workout and hope to improve on them. You can only accomplish so many goals at once. So if you want to prioritize these, make sure you are relatively fresh for each of your two weekly sessions and hit each of the 3 exercises HARD. This may mean temporarily consolidating some of your other lifts/bodyparts into separate sessions at other points during the week so you can devote adequate time and attention to these exercises. Arms Why You Have Small Arms (and how to fix it) I get asked about arm training a lot. The questions started really ramping up last year when I started to get somewhat regular with my YouTube videos and people started to notice that I do in fact have larger than average arms. So invariably, questions started rolling in about what super secret program I was following in terms of arm development. The secret is that there is no secret. The prescription I use for myself (and have used for many years) is basically identical to what I lay out in my power-building program. It’s what I use for myself. It’s what I use for my clients, and it’s what I suggest you use if you want bigger arms. Before getting into program specifics, let’s get into a few mistakes guys make when they are trying to grow their arms. As usual, many of the mistakes are made at the far left and right of the spectrum. Mistake #1: Dieting You will NOT grow your arms in a major caloric deficit. Sorry. They may look better if you start to train them a bit and drop some water and body fat, but they will not grow. I think arms, more than all other body parts, need to see scale weight move a bit before there is a noticeable difference in size. Look, if you are a great big fat guy, then don’t worry about your arms as a priority just yet anyways. Just get less fat. Spend the extra 10-20 minutes you’d spend training your arms at the end of a workout doing some prowler pushes. That’s a better use of your time. If you do decide that arms become a priority for you for a certain point in time, make sure you are eating in a way that supports muscle growth (see this article here for tips on mass building nutrition: http://www.andybaker.com/building-asimple-diet-for-mass/ Mistake #2 “If you just get stronger on the main lifts, your arms will grow with everything else!” True for a raw beginner. Not so true once you’ve got a few years of training under your belt. When a novice trainee starts Squatting, Deadlifting, Benching, Pressing, Cleaning, and Chinning for the first time ever, then yes, dedicated arm training is largely unnecessary. There is plenty of tricep work on the Bench and Press and plenty of bicep work if the trainee is chinning, but after the first several months (or maybe even up to a year or so) then size gains are going to level off and more specific work is likely needed. So if you’ve been training for several years and you still have small arms, then you probably need to train them. The notion that “squats make your whole body grow” is again, true, but only up to a point. Mistake #3 Over-training the arms This is probably the biggest mistake I see. In an effort to prioritize arms, guys will do way too much work. You can overdo things in terms of volume, frequency, or both. Often, trainees will add a dedicated bicep/tricep day to their week (which isn’t an entirely stupid thing to do) but then within that session they are cranking out way too much volume. Hammering your arms with 10-20 sets of curls, extensions, etc doesn’t work that well for most. There is simply a point in which more and more sets and reps just pushes a muscle beyond what is needed for a growth stimulus and becomes a liability. Some other guys will add some arm work 3-4 days per week, often a few sets of biceps/triceps at the end of all their main workouts. This doesn’t work well either. They don’t need to be stimulated this often to grow. Mistake #4: Too Heavy or Too Light Again, mistakes at both ends of the spectrum. I haven’t gotten my best arm growth from doing super heavy barbell curls or tricep extensions. I have used this approach in the past, but the end result mainly tends to be lots and lots of elbow inflammation and that is about it. The really heavy stimulus comes from our heavy pressing exercises, chins, and rows. Arms grow better from more moderate weights taken to failure in the 8-15 range (maybe lower on occasion to break through a strength plateau) with near perfect form. Likewise, you aren’t going to grow your arms much by tossing in a few token pump sets with half assed effort at the end of a workout. It’s better than not training them at all, but it won’t lead to any serious growth. You don’t have to go long or often, but you do need to go hard when it comes time to train the biceps or triceps. Mistake #5: Partial Range of Motion, Shitty form, and ignoring the Mind-Muscle Connection. I understand that many people don’t think that the latter matters that much or even exists at all. For the smaller exercises especially, it does. When you are squatting a heavy weight, you don’t need to focus on feeling the quads stretch and contract on every rep. This is going to happen regardless. But when we’re doing isolation work, we can’t just move the weight from point A to point B without an intense mental focus on feeling the muscles stretch and contract on every rep. If you aren’t walking away from your sets of curls with an intensely painful pump at the end of each set, you are likely not seeing much growth. Same with tricep work. If your arms just feel “tired” after working them rather than swollen and pumped I’d encourage you to work on that mind muscle connection during your sets and you’ll get better results. All your isolation type bicep/tricep work should be taken through as full a range of motion as possible. Focus on full deep stretches at the bottom end of the range of motion, and hard volitional contractions at the top. Control the eccentric phase as well. Mistake #6: Same exercises, same weights, same rep scheme My experience has been that isolation type assistance exercises need to be rotated in and out of the program much more frequently than the major barbell lifts. Meaning that you pretty much need to perform Squat, Bench, Deads, and Presses every week (or some very close variation thereof) but you don’t necessarily need to barbell curl or LTE every single week. Doing so leads to very quick stagnation and often overuse type injuries around the elbow and wrist. You don’t need 42 different curl variations, but maybe 3-4. Same with triceps. May 3-4 different types of extension movements that we rotate through on a weekly basis. You’ll progress your strength better this way, stimulate the muscle more effectively, and avoid some overuse type injuries. Ditto with rep scheme. Sometimes we may want to BB Curl some heavy sets of 6-8 with full rests, and other times we may want to do sets of 15 with 60 second rests. How to set up the template……. I usually build the program around a dedicated Bench Press focused session to start with. So if we assume you are going to have a dedicated Bench Press focused session, let’s place that on Monday for the sake of discussion (it can be whatever day of the week works for you). On the Bench Press day we’ll start with Heavy Flat Bench Presses, then move to Incline Presses, and finish the Bench work with Dips. After we are done with our Bench and Bench Assistance work (or call it “chest work” if you prefer) then we’ll move to Bicep training. I like doing Biceps here because the elbows and biceps are warm up, but not tired like if you train them right after doing Back work, which is very common practice. This allows us to go a bit heavier in a fresher state. Go with TWO bicep exercises. You’ll be rotating the two exercises around weekly or every couple of weeks with as many combinations as you want from a menu of maybe 4-6 exercises at most. The first exercise of the session is heavier usually about 3 sets in the 8-10 rep range. Maybe as low as 6 reps on occasion. Rest 2-3 minutes between sets and focus on moving as heavy a weight as possible for an average of 8 reps per set with perfect form, full range of motion, etc. Adjust the weight as needed (down) from set to set to make sure you are keeping your reps around 8ish and maintaining perfect form. These sets should be taken to failure. We aren’t doing a ton of volume here, so we want quality, fatiguing reps. If you stop at 8 reps with 2-3 reps left in the tank you aren’t getting enough stimulus. The second exercise is lighter with sets in the 12-15 rep range. Rest periods will be shorter and loads will often be dropped set to set to maintain the volume and form. I may often use drop sets, rest-pause sets, etc here to keep the reps high, sometimes even up to 20 or so reps. The object here is metabolic stress…..i.e. get a massive pump. That’s it for biceps. 6 intense focused sets taken to failure with perfect form, and full range of motion. Sample: Bench Press 3 x 5 Incline Bench Press 3 x 8-10 Dips 3 x 10-15+ Barbell Curl, Dumbbell Curl, Incline Dumbbell Curl, DB Preacher Curl, etc 3 x 6-10 Barbell Curl, Dumbbell Curl, Incline Dumbbell Curl, DB Preacher Curl, Cable Curl, Machine Curl 3 x 12-20 A little tip……if you struggle with Dips after Bench / Incline, do the first heavy bicep movement as the third exercise of the day, then do dips, then do the second bicep exercise. This short break will allow you to crank out more dips. Again, assuming the Bench Press / Bicep Day is on Monday, then we’ll do a dedicated Back Training session on Friday. If biceps are a priority, start this session off with Chins or Weighted Chins and then do all your other exercises like BB Rows, DB Rows, Pulldowns, etc. This is our second bicep stimulus of the week, but it’s kind of an “indirect” stress on the biceps. This is part of my direct / indirect system that I use with all muscle groups in my power-building program. The Back Day usually has around 15 total sets for back, and about 10 of those sets have a bicep component to them. The rest usually rear delt work and shrugs. Now for Triceps……. So if we are doing Bench, Incline, and Dips on Monday, all of that serves as our “indirect” tricep stimulus, although the reality is that it’s pretty damn direct. The Dips on Monday I like to keep in the higher end of the rep spectrum, like 10-15. This is partly because I like to do Dips again on Thursday as part of a dedicated Shoulder / Tricep session. On Thursday, I like to take the Dips heavier, with added weight in the 6-8 rep range. This also serves as our “indirect” chest stimulus later in the week after hitting it really hard on Monday. If I need to give my shoulders a break, I will sub out the Dips with heavy Close Grip Benching or even Floor Presses as my heavy tricep exercises and my “indirect” chest stimulus. I follow that up with an extension exercise that I change up every week. This is worked in the 8-15 rep range, often with a drop set or two on the final set to really pump some blood into the muscle. We rotate through Lying Tricep Extensions (with EZ Bar or Dumbbells), French Press (with EZ Bar or unilaterally with a Dumbbell), and Cable Pressdowns. And that’s it for triceps. 6 dedicated intense sets on Thursday (after Overhead Pressing). The Sample Week……. Monday: Chest / Biceps (plus indirect shoulder, triceps) Bench Press 3 x 5 Incline Bench Press 3 x 8-10 Dips 3 x 10-15 Seated DB Curls 3 x 8-10 Barbell Curls 3 x 15 (descending sets with 30-60 sec rest) Thursday: Shoulder / Triceps (plus indirect chest) Standing Shoulder Press 3 x 5 Seated DB Press 3 x 8-10 Side Delt Raises 3 x 15-20* Heavy Dips 3 x 8-10 Lying Tricep Extension 3 x 8-12 + Drop Set x 8-12 *the side delt raises serve as a nice break for the triceps between the overhead pressing and heavy dips Friday: Back, Traps (plus indirect biceps) Weighted Chins 3 x 8-10 Barbell Rows 3 x 8-12 Seated Cable Rows 3 x 12 Rear Delt Raises 3 x 15-20 Shrugs 3 x 15 Follow this protocol as I’ve laid out here and your arms will grow. Use the full KSC Method for Power-Building if you want to see how I lay out an entire training program using the Direct / Indirect training system for muscle hypertrophy and physique development. Got Guns? – 5 Tips for Bigger Arms Don’t lie to yourself – you know you that filling out your T-shirt sleeves with a little more mass would be a cool side effect of your strength program. I know that most of my clients are not looking to become bodybuilders, but anyone that trains with weights consistently likes to add a little muscle mass to their frame, and for a lot of guys it starts with the arms. One of the biggest mistakes trainees make when trying to build up their arms is too much focus on the biceps. The reality is that the triceps make up the large majority of the upper arm mass and that’s where most of your attention should be. The side benefit of added tricep work is that your Bench Press and Overhead Press will likely improve as well. The tricep muscle is composed of three heads and complete development of the muscle mass means that you need to be performing exercises that target all 3 heads. These are not really 3 separate muscles and you can’t truly isolate one head from the other. Basically any pressing exercise or any tricep isolation exercise will train all 3 heads. But through careful exercise selection you can place emphasis on one specific area. If you want to test this out you can use the “soreness” test to see where each exercise focuses most. Simply perform one exercise for 5-8 total sets of 8-12 reps and see where you are sore the next day. As you rotate through different movements you will notice that localized soreness occurs in different parts of the arm. Tip #1: Train the Medial Head with Lying Tricep Extensions and Standing Cable Pressdowns In reality, both these exercises do a pretty good job of training all 3 heads fairly comprehensively. Both of these movements place the humerus in a position that is either directly out in front of the torso (LTE) or about 45 degrees out in front of the torso (pressdowns). In this position all 3 heads are very active and this makes these two movements ideal candidates as your primary tricep isolation movements. I prefer to do LTE’s strict, meaning I lower the bar down to the forehead. Depending on the length of your forearms the bar will naturally fall somewhere between your eyebrows and your hairline. Use the inside grip of an ez-curl bar for reduced stress on the elbow and wrist joints. I like to do 3-5 sets of 8-12 reps on these. Occasionally I like to take these heavier into the 4-6 rep range but only on occasion. Going too heavy on these can tear up the elbow joints. I like a straight bar or slightly cambered bar for pressdowns and generally do these for higher reps and a lot of volume. 3-6 sets of 10-15 reps on short rest intervals will blow your triceps up. Tip #2: Train the Outer Head with Dips Often called “Squats for the Upper Body” , Dips do a good job of developing the triceps as well as the chest and shoulders. Dips allow you to load up a little heavier and push some bigger weights which can help you break through strength plateaus. Because these are a multi-joint movement you can take dips heavier more often without the stress on the elbows. Weighted Dips are excellent if you are hitting sets of 10+ with just body weight. Most of the time we use a belt with weight hung from a chain. If you are really feeling like punishing yourself you can do Dips against band tension. To do this you have to SECURELY fasten a band to the bottom of your dip station and then loop the other end around your neck. As you get to the top of the movement the tension on the bands increase and your triceps really have to work to lock out. The continuous tension of the bands and the difficult of the lockout will give you a tricep pump like you have never experienced. These are an advanced movement though so please be careful with these. Tip #3: Train the Triceps Overhead to Develop the Long / Inner Head Less common than the Lying Tricep Extension (LTE) is the Overhead Tricep Extension or French Press. These can be done seated or standing, and again, use an ez-curl bar. With arms straight overhead, lower the bar behind your head and then return to lock out. This will target the long head of the tricep or the length of muscle that runs on the innerunderside of your arm more than any other exercise. According to Westside Barbell’s Louie Simmons this is the most important area of the tricep to develop. Especially on Overhead Presses, the long head of the tricep is extremely important. Another way to blast this area of the tricep is to do some higher rep sets of Overhead Presses. If you are used to training with sets of 5 or less, throw in a few sets in the 8-12 rep range and you’ll feel the pump in your triceps (as well as your delts). Tip #4: Stop Doing Alternating Dumbbell Curls If you want the biceps to grow, then understand that they respond well to exercises that place them under continuous tension. Alternating DB Curls which are often billed as a “mass exercise” allow tension to come off of one arm while work is being done with the opposing arm. DB Curls are fine, but if you are going to do them, then do both arms simultaneously and don’t rotate the wrists – keep the palms up throughout the whole movement. Rotate these around with standard Barbell Curls and you’ll grow your biceps. Training the biceps is really really simple in terms of exercise selection. The key is not to rotate through a bunch of different curl variations, but rather work through a wide variety of rep ranges. With either barbells or dumbbells, do a small volume of work in the 4-6 rep range to keep strength moving up, but focus the majority of your volume on sets of 8-12 with strict form. Tip #5: Don’t Forget About the Side Delts Typically “arms” are thought of as triceps and biceps, but if you look at a well muscled trainee from a profile view – a big rounded set of side delts completes the “look” that most guys want. For the most part, developing a bigger stronger Overhead Press will take care of this, but you can pack on a little added mass through seated dumbbell presses, behind the neck presses, and/or lateral raises with a pair of dumbbells. Behind the neck presses and seated dumbbell presses (performed with the elbows flared out to the sides) put a little added emphasis on the side delts as compared to a standard military press where the arms are more in front of the torso. Lateral raises are essentially useless in terms of performance, they are purely used for aesthetic purposes. But if you want a better physique – 2-3 quick sets of side laterals after you press only takes a few minutes and doesn’t add that much in terms of overall stress on the body. Use strict form and use higher reps in the 10-20 range and chase a big pump in the delts. Strengthening & Growing the Biceps (my favorite simple method) Bicep training is not difficult, complicated, and it shouldn’t take a lot of time. I maybe spend 15 minutes, once per week, training my biceps for a total of about 6 sets. I’ve never done much more than this and I’ve got pretty decent sized biceps. I’ve just stayed consistent with it over the years and it’s paid off. Biceps, in my opinion, are underrated as an important muscle group for overall total body strength. While certainly not on the level of squats, presses, and deadlifts, strong arms are important and if you want to maximize both size and strength in the arms, you need to train them and you need to do lots of loaded elbow flexion – i.e. curls. Many regard biceps as purely cosmetic (and of course we all have our egos to feed, and big arms are cool) but I use curls regularly in my programming for certain athletes – especially grapplers, and I also use them in my programming for seniors, as an upper body exercise that can be done standing. For many seniors, they cannot perform standing presses well. Presses are excellent for senior who need to do as much barbell work as possible on two feet for total body strength as well as balance. But many senior have very limited range of motion in their shoulders and overhead work is problematic. So I use a lot of standing barbell curls. When you take them fairly heavy there is not just bicep activity but also some work for the abs, low back, and traps. In a basic strength program for an athlete or for seniors curls are usually performed just once per week for about 3 sets of 8. Occasionally dipping down into the 3-5 rep range for athletes. In my Power-Building programs, we perform our Bicep Training on our Heavy Bench Press Day after we Bench and do our supplemental chest exercises such as Inclines, Dips, and Dumbbell Presses. I’ve always liked the pairing of Chest/Biceps. Lots of volume on the Bench and it’s variants is fatiguing and after all that pressing work I was never very strong on direct Triceps work. However, after training chest, the biceps and elbows are warmed up, but not fatigued, so I can train them pretty heavy and relatively fresh, and it doesn’t take very long to do, which is also good. Training the biceps after my back sessions also seemed rather pointless to me as my biceps were pretty well smoked from all the chins, pulldowns, and rows. Plus, overall general fatigue is higher after a hard back session than a hard chest session so I don’t like doing anything on a back day other than back. Furthermore, for maximal hypertrophy I like stimulating a muscle twice per week. Once directly and once indirectly. I usually train the biceps early in the week (directly) after chest, and then later in the week they get hit indirectly when I do my chins and rows. So this works out perfectly scheduling wise. I use the same philosophy for Triceps. I hit them directly with lots of dips, lying extensions, and cable pressdowns one day of the week, and on another day of the week they are stimulated again when I do my heavy chest training. A simple routine for bicep strength & growth…… For biceps I rotate each week between workout A and workout B. The biceps only contract one way and so you don’t need 34 different curl variations. But I have found that better growth and less elbow irritation occurs with a small amount of variety in the training plan. In Workout A, I start with heavy Barbell Curls and I normally do 3 working sets of 8 reps. Following the Barbell Curls I do a Single Arm DB Preacher Curl for 3 sets of 10-15 reps. Heavy Barbell Curl 3 x 8 Single Arm DB Preacher Curl 3 x 10-15 For the Barbell Curl I perform maybe 2-3 warm up sets with lighter weights to make sure the biceps and elbows are thoroughly warm and then I do 3 sets of 8 across with a straight weight, trying to add weight each week. I keep these fairly strict but if I have to “cheat” a little bit on the last rep or two I will. Every 3rd workout or so I will drop the target rep range down to 4-5 and really try to load up heavy. I might do this for all 3 worksets or just the first workset and then back off to sets of 8 to finish out. I find that the occasional really heavy BB Curl workout is necessary to keep strength gains going. I keep rest times on my heavy BB Curl worksets at about 3 minutes. For the Single Arm Preacher Curls I usually use an adjustable incline bench set around 70-80 degrees. I don’t like the standard preacher curl benches because the angle is too horizontal in my opinion. Usually those benches are around 45 degrees and I think a little more vertical is better. I select a light to moderate load that causes failure between 10-15 reps and I alternate arms with little to no rest between arms. So the reps are high and the rest is short and I’m aiming to pump as much blood into the muscle as possible in order to stimulate growth. I won’t hesitate to the lower the weight from set to set to keep rest time down and reps high and maintain a full range of motion. Aim for a deep prolonged stretch at the bottom of the exercise and squeeze the hell out of the biceps at the top. Keep the wrist as supinated as possible through the whole range of motion for maximum biceps activation. If you can straighten your arms at the end of this workout you did it wrong. In workout B I start off with either a Seated DB Curl or Incline DB Curl. An incline DB Curl should have the bench set around a 60 degree angle and this allows a deeper stretch at the bottom of the range of motion and you’ll use a little less weight than you will with a seated DB curl at 90 degrees. Either way, curl with BOTH arms simultaneously. I don’t like the old fashioned alternating DB Curl because it takes tension off the non-working bicep for too much of the exercise and it allows form to get sloppy. I like continuous tension on bicep training. Again, try and keep the wrist as supinated as possible for the whole exercise. These are done for 3 worksets (after 2-3 warm ups) for 6-8 reps. Strict but heavy. 2-3 minutes between worksets. After the DB Curls, I go back to the Barbell Curl again, but this time the loads are lighter and the reps are higher. Usually 3 worksets of 10-15 reps. Rest times are just 1-2 minutes, but I will very often just perform this exercise as a double drop set. So I might do a workset of 10 reps at 95 lbs, strip it down to 75 lbs and immediately perform another set of 10-12 reps, strip it down to 55 lbs, and then immediately perform 10-15 more reps. So no rest between sets. Yes, you will use some embarrassingly light weights at the end of that double drop set, but the object here is not strength – it’s maximal blood flow and metabolic disruption, which is a stimulus for growth. Seated or Incline DB Curls 3 x 6-8 Barbell Curl 3 x 10-15 That’s it. I find that this very simple routine 1x/week is sufficient for growth, especially if you are doing a back training session on another day of the week, preferrably 2-3 days before or after this session. Lately my Chest/Bicep days have been falling on Sundays and my Back Day falls on Thursday. If you really want to focus on bicep strength and growth, start all your Back Day sessions with Chin Ups, rather than with Pull-Ups or Rows and you’ll get some good bicep stimulation there. I’ve also found that when I regularly train my biceps hard, that I am stronger on my back exercises, especially my chins and pull ups. So, for all you closet bodybuilders – you now have my permission to curl. Just don’t do it in the squat rack. An Easy Tricep Training Schedule If you want your arms to grow you gotta train your triceps. If you want your Bench to move, you gotta train your triceps. It’s true that the triceps get tons of work through Benching, Overhead Pressing, Incline Pressing, etc and for a relative beginner or early intermediate trainee this might be all the stimulus that is required to get the arms to grow. But over time, the work must become more specific, more isolated, and more focused and intentional. The biggest mistakes I see people making with their arm training in general lies on either end of the spectrum. Group 1 wants to train the arms directly 3 times per week or sometimes even more. I don’t think this is productive long term strategy and I rarely see guys who are trying the super high frequency approach make much progress. For triceps, direct training 1-2 times per week is sufficient. Group 2 might train the triceps 1-2 times per week, but the approach his lazy and hohum. The standard 3 sets of 10, not even close to failure, never tracking weights or reps…what I call clock-punching. Putting a check in the box. Clock punchers and box checkers never get any growth either. When you are trying to make small muscle groups grow you must create fatigue and muscle damage. You need to be training to failure. You need to be varying your exercise selection, and you MUST be trying to chase rep and/or weight PRs every time you train a movement. Training this way will require a moderate volume and a moderate frequency. You can go high volume and you can go high frequency. But doing so requires less intensity and less intensiveness. Intensity being defined as load (absolute as well as relative to the rep range you want to train in) and intensiveness is basically the amount of EFFORT you put into your sets and how close you are training to failure. Focus on quality and not quantity will yield you better results in the long term. I honestly think that if you are doing a lot of Benching, Overhead Pressing, and variants of each exercise every week, then you can train with as little as 6 sets of direct tricep work per week and get great results, provided each of those sets is actual meaningful work. Don’t count bullshit sets. Work sets should generally terminate in muscular failure and create a fairly significant pump in the tricep. There is debate on the actual significance or effectiveness of the “pump” to muscular growth. My own personal experience as a lifter and coach is that I’ve never really seen anyone grow their arms to a significant degree without it. At the very least the pump is an excellent indicator of how effective your sets and reps are, even if the pump itself is nothing more than a meaningless short term accumulation of blood and metabolic waste products in and around the muscle cells. So don’t count warm up sets, work sets only. Take every work set to failure and occasionally beyond failure. What I generally like to do is set up two different “sessions” for the triceps per week, 2-3 days apart. I “airquoted” sessions because these sessions are generally tacked onto the end of other upper body workouts, not necessarily given their own day. In one of the sessions always like to include Dips. Dips are unique because they put the shoulder joint in an extreme position of extension. This targets the outer head of the tricep the best. The outer head is the most visible head of the tricep from an aesthetic point of view, but it’s often described as the “lazy head” in power lifting because it’s believed to contribute the least to the Bench Press. The only other exercise that trains the triceps with the shoulder in extension like this is the tricep kickback. But the kickback is really pretty worthless as an extension movement though just from how the movement is loaded and for a good portion of the exercise the tricep is really not under tension. If you were going to get into kickbacks, you’d want to do them with bands or cables rather than DBs for the continual tension……but really……just do Dips. If you can’t do Dips, find an assisted machine, use bands for assistance, or even find a seated dip machine. Several manufacturers make them, and many are quite good at hammering the triceps, especially for very large guys who maybe struggle with dips. If you want to add resistance to the Dips you can do the standard way which is to add weight to a dip belt. Or if you want to look extra hardcore you can put chains around your neck. However, if you want to use the Dips to really overload the triceps, do your Dips against band tension. Put one end of the band around your neck and anchor the other end to the floor. This is superior, even to a weight belt, for added resistance to the triceps. I generally like to place the Dips in a spot in the training schedule where they can be done relatively fresh. So if I begin an upperbody workout with Bench Press or Overhead Presses, I might put in a “pulling” movement second (chins, pulldowns, rows, curls, etc) and then hit the Dips 3rd after the chest, delts, and triceps have had a bit of a rest. I find that my clients can move SIGNIFICANTLY more weight for more reps after even just 10 minutes of rest from the main pressing movements. On another day of the week I’ll program in an extension movement. For the smaller exercises you’ll find that you need to rotate the movements out fairly frequently. This might be every week or it might mean staying with 1 exercise for 2-4 weeks until progress halts and then rotating out to a new exercise. I usually set up the rotation like this: Week 1: Overhead Extension / French Press (w/ EZ Bar, Machine, or single dumbbell/unilateral) Week 2: Lying Tricep Extenison (w/ EZ Bar or dumbbells) Week 3: Cable Pressdowns Not even counting all the different grips for the cable machine, this simple rotation basically gives you 6 variations to work through over time. Each week the shoulder is placed in a different degree of flexion/extension and so the emphasis shifts week to week to different heads of the tricep. You can’t really isolate any one head of the tricep from the other 3….it’s one big muscle that acts together when the elbow and shoulder are extended but the emphasis does certainly shift. All you have to do is track your soreness patterns to confirm. In general, the greater the amount of shoulder flexion (arms overhead) the more work you’ll place on the long head / inner head of the tricep. As you move down the spectrum (arms out in front of you (LTEs) -> arms pinned down to sides (Pressdowns)-> arms behind you (Dips), the more you shift emphasis from inner to outer head. Now, with whatever variations you choose to perform over the course of weeks and months…the most critical factor is that you are tracking your performances week to week and constantly trying to beat your record book. You can beat your records via reps or weight. So if on a given day you did 3 sets of 12 with 100 lbs on a lying tricep extension, then the next time you train this movement you need to either add some weight or add some reps. It doens’t really matter, but something must go up all the time or you aren’t going to be growing or getting stronger. I like to set “baseline” volume goals for each exercise to try and work towards. So let’s say we go with 3 sets of 12 reps as a baseline for an extension exercise. If on a given week we perform 3 sets of 12 with a given weight, then the next week/session we are going to add weight. It’s likely the reps will fall. Lets say in Week 1 we do 3x12x100lbs and in week 2 we do 3×12,10,9×105 lbs. From there we will work on adding reps and not weight until we hit 3x12x105. Then we’ll bump up in weight. It might take several attempts to move from 3×12,10,9 to 3×12 and that’s okay. Even if we add 1 rep on just 1 set, we are moving in the right direction. This is how progress is made. Do this with every exercise and in general triceps will be be trained in the 8-15 rep range. I don’t always use a sets across type approach for triceps because they are so susceptible to fatigue. I very often use descending sets with tricep work in order to maintain volume and get more quality work sets in closer to failure. For instance…..if I go 3 x 12 x 100 lbs then it’s likely that the first two sets were not really close to failure at all. Maybe only the final set was all that fatiguing. It’s more likely you’d see me programming something like: 110 x 10 100 x 10 90 x 10 With all 3 of these sets taken to failure. I can build up more fatigue and do my first work set (when I’m the most fresh) with a higher load. You can also implement things like Borge Fagerli’s Myo-Rep system or Dante Trudel’s RestPause type sets for your tricep work. Both are very similar protocols. I personally prefer Dante’s system, but either is effective for getting in a lot of reps in a highly fatigued state. This can be a powerful stimulus for growth. Again, don’t get carried away with volume and frequency. I’ve gotten the best growth from my own training and that of my clients by setting people up on an upper body split that looked like this: Monday: Heavy / Max Effort Bench or Bench Variation Incline or DB Bench Pressing Rows Rear Delt/Side Delt/Traps Tricep Extenison (rotate 3-6 different movements) 3 x 8-15 (descending sets) Thursday: Light / Speed Bench Overhead Pressing Chins / Pulldowns Dips 3 x 8-15 (rotate bands, weight belt, and/or bodyweight each week) Biceps Note that on this schedule I’m trying to prioritize the triceps by allowing them to get trained in as fresh a state as possible, thereby maximizing load, and volume and frequency are quite moderate because we are focusing instead on effort, intensiveness, and beating our log books every time we train a movement. Nutrition & Cutting Building a Simple Diet for Mass We all know that to grow we need to eat. And if we want to grow a lot we need to get ourselves into a caloric surplus and we need to stay there. This is one of the few points on the web that isn’t really a point of contention amongst lifters and coaches. The debate always comes over the details. How much protein? How many carbs? What about fat? What kind of fat? Can you build muscle without fat? How much body fat is too much? What about pre/post workout nutrition? Intermittent fasting? Keto? Paleo? It goes on and on. It’s confusing by design because everyone is trying to sell something new and revolutionary in the diet world. It’s also because producers know that consumers want something easy, and everyone wants to be huge, ripped, and strong without having to do all the hard annoying shit that gets you huge, ripped, and strong. Unfortunately it doesn’t work that way. Even the honest brokers in the industry contribute to the misinformation by parroting the results of various “studies” that are inherently flawed in their methodology and don’t square at all with what we see actually working (or not working) in the real world. Some dishonest brokers manipulate the results of the studies in order to sell supplements or the newest diet fad. What I will propose is nothing new or revolutionary. There is variations of this all over the web, magazines, books, etc. (maybe there is a reason for that?) But it’s mainly just what I’ve seen work with myself and others in the gym over the past 20+ years or so. It’s practical, simple, and fits with the goals of most guys trying to put on mass. That is to say, we want to get bigger and gain weight, but not so much weight that we put on 25 lbs of blubber in the process. A little fat is inevitable, too much fat doesn’t help us build more muscle, and in fact may slow that process down. Your abs may not stay visible as you are putting on weight, but you don’t need your belly hanging over your belt either. So, let’s walk through the process I use when building out a diet for a client……. Protein Intake Step One is to set the protein requirements in place and then spread that out over 5-6 meals. Not 2, not 3, 5-6 is best. I do believe we grow and recover best when protein is injected into the system roughly every 3 hours in moderate doses. Unless you are Ronnie Coleman, I don’t think your body can do much with 80-100g of protein at a sitting, and you cannot store protein for later. So eating waaay over and above what you can assimilate at a sitting is a waste of calories, IMO. For most of us 30-50 grams is probably the sweet spot. So for a 200 lb male who wants to slowly bulk up to 225 lbs, we’re looking at about 200-250 grams of protein per day (yes, I like the 1 – 1.5 grams per lb of body weight rule, assuming adequate carbs and fat are supplied for energy). So let’s just say we’re going to average about 40 grams of protein per sitting, we’re going to spread that out over 6 meals per day. Breakfast – 40g Mid-morning – 40-50g Lunch – 40g Mid-afternoon – 40-50g Dinner – 40g Before Bed – 25 – 50g Post-workout – 25g. This will average out to be about 240 grams per day, which is perfect. (+/- a few grams is fine, don’t get neurotic). The protein requirements will basically stay fixed 7-days per week. Again, we can’t store protein so feedings need to be continual, and if we are training hard and heavy 3-5 days per week, then we can assume our body is pretty much in a constant state of repair/recovery so there is really no reason to ever lower these requirements. In fact, I’d argue it’s just as important to keep protein high on rest days or even deload weeks as on training days. Now, as far as the TYPE of protein we are eating……as long as it comes from complete sources (egg, meat, fish, dairy) it’s not terribly important, however, I do like to vary my protein sources just to cover my bases. I don’t know if there is anything to that to be honest, but it makes some sense, and there isn’t any risk in doing so. For the mid-afternoon and mid-morning meals, I typically recommend protein shakes here. Why? Because they are easy and convenient. Usually around 10 am and 3-4pm is when most working adults are busy with their jobs. It can be inconvenient to sit down and plow through a chicken breast or a steak at this time, and if you are busy with meetings, sales calls, etc, it’s just easier to gulp down a shake really quick then heat up or cook meat. I try and have clients cook meat just 1x/day (or cook a bunch in bulk every 3-4 days). And so whatever type of meat you cook for dinner (chicken, steak, fish, etc) just cook a double portion and make that the next days lunch. 40g is about 6 oz cooked of most lean meats. Again, it doesn’t have to be exact, but around 6 oz would be good in this example. It could be 4 oz for a smaller individual or 8-10 oz for a larger individual. Breakfast is usually eggs or egg whites. I am partial to whole Omega-3 eggs for the micronutrient profile as well as the healthy fats, but egg whites can be quicker in the morning if you are in a rush. You actually don’t need to even cook your egg whites. 1 carton of 100% liquid egg whites is 40-50g of high quality protein and can be drunk straight. It’s pasteurized and will not make you sick. They have no taste, but the texture is off putting for many. This is a quick and easy protein fix and I prefer it to simply having another shake. I try not to get too many meals per day with shakes as the primary protein source. If I do egg whites during the work week, I try to switch to whole eggs on the weekends when I have more time to cook. Bedtime is often 1 cup of low-fat cottage cheese. Cottage cheese is a slow digesting protein that will stay in your system for a while, while you sleep. On non-training days, you can mix 1 cup of cottage cheese (25g protein) with 1 scoop of chocolate whey for a pretty good protein pudding. On training days, just have the 1 cup of cottage cheese as the single protein scoop will be used in your post workout drink. So now we have: Breakfast (6-7am) – 6 whole Omega-3 Eggs or 1 Carton of 100% Liquid Egg Whites (35-50g) Mid-morning (9-10am) – 2 scoops of Whey Protein (40-50g) Lunch (12-1pm) – approx 6 oz of cooked chicken breast, fish, lean steak, or lean ground beef/turkey (~40g) Mid-afternoon (3-4pm) – 2 scoops of Whey Protein (40-50g) Dinner (6-7pm) – approx 6 oz of cooked chicken breast, fish, lean steak, or lean ground beef/turkey (~40g) Bed-time (9-11pm) – 1 cup cottage cheese (25g) Post-workout – 1 scoop whey (20-25g) or add this to night time meal on rest days Fat Intake I actually don’t have clients add in a lot of excess fat sources (olive oil, nuts, avocado, etc) to the diet when trying to build mass. I simply ensure that at least several days per week we are taking in protein sources with a higher fat content. So while chicken breast and egg whites are 100% a-ok, just make sure that several times per week (or even daily) you are getting in some whole eggs, salmon, some steak, or ground beef. Even the leaner sources will have a decently high fat content. With enough carbohydrate present in the diet, we don’t need to add in tons of excess fat. I avoid very high content fat sources like 80/20 ground beef, sausage, or deli meats (salami, etc). Stick to Sirloin / NY Strip steaks, and 90/10 ground sirloin, etc Carb Intake Now comes the trickier part. Carbs is where we really manipulate things to find the right balance of total calories. By and large this will have to be trial and error-ed in and out of the diet to find the right pace for gaining weight. Protein intake stays SET, and we don’t really track fat down to the gram. With weight gain, about .5 – 1 lbs per week is plenty for most if you are training your ass off. Faster than about 2-4 lbs per month you might find that you are adding more body fat than you want. So we just manipulate carb intake until we start hitting that sweet spot of about .5 – 1 lbs per week. Remember that this number might be close to 50/50 water retention and lean tissue with an increased carb intake. So at 1 lb per week of weight gain, we might be looking at a half lb of lean tissue and a half pound of water weight on average. Lean tissue is good, water is inevitable, but we want to minimize fat accumulation. If you are more of an endomorphic body type (i.e. a natural fatty) with a slower metabolism and a higher sensitivity towards carbohydrate, then start with about 1 g of carbs per pound of body weight. If you have a higher metabolism and struggle to gain weight then start around 2g of carbs per pound of body weight. This is a very general starting point and may inevitably have to be adjusted up or down week to week based on scale and mirror feedback from each individual. But now we have something that looks like this for someone shooting for 200g of Carbs per day…… Breakfast: 1/2 cup of oatmeal (uncooked) ~27g Midmorning; 1 Banana ~30g Lunch: 1/2 cup rice (uncooked) ~35g Midafternoon: 1/4 cup Cream of Rice (uncooked) ~35g (just throw this into the shake) Post-workout: 1 bottle of Gatorade ~60g Dinner: 1 Red Potato ~25g This comes out to roughly 215 g of carbs per day which is close enough for a starting point. If the lifter is not putting on weight with this amount of carbs then we simply bump things up by maybe 50-100g per day. Using this set up, we’d simply double a few of our portion sizes. For an extra 50g per day, just bump the oatmeal up to 1 cup (uncooked) and add an additional red potato at dinner. Now we’re at 250g per day. If we need more still, then we could get an additional 50grams (approximately) by doubling our rice portion at lunch (35g) and adding in a small apple or orange to the pre or post workout meal (15-20g). So for 300g of carbs per day, our menu is like this: Breakfast: 1 cup Oatmeal (uncooked) – 54g Midmorning – 1 Banana ~30g Lunch – 1 cup Rice (uncooked) ~70g Mid-afternoon – 1/4 cup Cream of Rice ~35g Post-workout – 1 bottle of Gatorade ~60g, + 1 orange ~15g Dinner – 2 red potatoes ~50g This gives us approx 315g of carbs. Again, close enough as an estimate. We would follow the same pattern in reverse for a trainee accumulating too much body fat while bulking. Simply remove about 50g of carbs at a time for a week at a time and watch the scale to see what happens. The moral of the story is simply to start with an estimated baseline of carbs and then adjust 50-100g at a time each week based on feedback. Don’t adjust daily or you can’t get an accurate picture. And don’t adjust 10g at a time. That doesn’t represent enough change to even cover the inevitable inaccuracy in our food estimates. So make changes 50-100g at a time and stay with the new numbers for a week before going up or down even more. Trace Macros…… What I mean by this is the trace amount of carbs we get in our fibrous vegetables, like broccoli. Or the trace protein we get in our oatmeal. I never factor those into the equation. The reality is that unless you are getting ready to step on stage for the Mr. O, then you don’t need to be that OCD about your macros and calories. Instead we need to be in the ballpark on everything and we need to be consistent. An extra 5g here or there of anything doesn’t matter. Now, lathering your chicken breast in a 1/2 cup of BBQ or Teriyaki sauce? Yeah, you might be putting in an extra 20g of sugar you didn’t realize you were consuming and that can throw you off. So read labels and watch for hidden carbs and fats. If your protein drink has 25g of carbs, you need to factor that in. If it has 2g, don’t worry about it. Count the carbs from starch and fruit. Count the protein from meat, shakes, and eggs. Don’t count fibrous vegetables as anything, but include them in your meals for the fiber and micronutrients. Keep it simple. Sodium Sodium isn’t going to make you fat, but it does lead to water retention. This is mainly important because it skews your readings on the scale and you can’t accurately gauge weight gained or lost. If you marinade your steak in an extremely high sodium marinade on Thursday night and weigh yourself on Friday morning, you might be up an additional 2-3 lbs. You may not realize that this is mainly water retention from a giant sodium bomb the night before. Bagged chicken breasts are notorious sodium bombs. I recommend eliminating things like marinades and other sauces (soy, etc) that have very high sodium content. Learn to eat without a shit ton of condiments. Use sodium free seasonings on food and use Mortons Light Salt for your food. It has less sodium and does an adequate job of flavoring your food. The Wrap Up…… As a final summary, below is a picture of a diet that is about 200g of protein per day and 200g of carbs per day using the examples from above. If you are not building muscle or if you are just getting fat, start eating more in line with these recommendations and you will grow in all the right places. Effective Diet is like training……it’s so simple a fool cannot comprehend it, and so brutally hard that a lazy man will refuse to accept it. 7:00am: 6 Whole Eggs scrambled with onion and peppers + 1/2 cup Oatmeal (uncooked) made with water 10:00am: 2 Scoops Whey in water + 1 Banana 1:00pm: 6 oz cooked chicken breast + 1/2 cup rice (uncooked) + 1 cup broccoli 4:00pm: (Pre-workout): 2 scoops Whey mixed with 1/4 cup Cream of Rice cereal (dry) + 1 Orange 6:00pm: (Post-workout): 1 scoop Whey mixed with 1 bottle of Gatorade (immediately post workout) 7:00pm: 6 oz Sirloin (cooked) + 1 red potato + Asparagus 10:00pm: 1 cup low-fat cottage cheese Most guys send me a diet that looks like this when I start working with them as clients: Breakfast: Bowl of cereal and a piece of fruit Lunch: Sandwich and some pretzels Snack: some fruit or almonds Dinner: whatever my wife makes Of course they also include about 42 different types of supplements they are taking. Throw that shit out. Spend your money on food if you want to grow. And if you are eating like this, your program won’t matter, so stop engaging in internet fighting about volume vs intensity, high bar vs low bar, training frequency, or whatever. None of that shit matters when you don’t fuel the growth and recovery. Training is simply a stimulus. That’s it. We grow and get stronger while we’re sleeping and eating. Start treating your diet with as much focus as your training and you’ll find that again, whatever program you are currently following will all of a sudden become a lot more effective. Best Strength Program While Cutting Body Fat This might be the most asked question I get on a weekly basis. If not, it’s definitely top 5. It goes something like this: “Andy – I want to keep getting stronger, but I also want to drop some body fat. What’s the best type of strength program to use while I’m cutting body fat?” I don’t know that there is ONE single program to use that works 100% of the time with every trainee in every situation, but I would say in general my favorite barbell-based strength program to use during a fat loss phase has to be the Classic Heavy-Light-Medium protocol. If you don’t know what the Heavy-Light-Medium template is, search my blog for a 3-part article series I wrote a few years ago that goes into pretty good detail on the subject. The program is also discussed in Practical Programming for Strength Training 3rd ed, and of course Bill Starr’s classic – The Strongest Shall Survive. It is important to understand that the Heavy-Light-Medium template is just that……a template. It’s NOT a “program.” A program is something very specific. It’s sets, reps, loads, exercise selection, etc. It’s written out for an individual or very specific population. The Heavy-Light-Medium template can be manipulated dozens of different ways to form a specific program for a specific individual to chase a specific goal – general strength, competitive strength sports, non-barbell sports, hypertrophy, etc. It’s extremely flexible and that’s one of the reasons I like it so much. But the purpose of this article is to examine WHY I like it so much for a client or trainee who is trying to preserve or even build as much strength as possible, while cutting body fat. #1: Big Lift Frequency For anyone who has ever done a weight cut before, you’ve probably experienced the defeating feeling of crawling underneath the bar and having the barbell feel about 50 lbs heavier than it actually is! I’ve even re-racked the bar to double check and see if I misloaded it! Of course, we know, that the weight didn’t get 50 lbs heavier over the course of the week if you are training correctly……you just got smaller! Even if your bodyweight is only down 2-3 lbs, it often feels like the load on the bar increased by 10 times that much. If your fat loss strength program only calls for doing each lift 1x/week and you are losing weight on a weekly basis, that barbell is going to feel exponentially heavier week to week, even if you are only making small incremental increases week to week. One of the ways to mitigate this de-motivating experience is to train your primary lifts with a relatively high level of frequency. At least 2-3 times per week. This helps you “keep pace” with the weight loss. In addition, higher frequency training keeps the nervous system “primed” to more efficiently perform whatever exercises are being frequently repeated throughout the week. Usually, when we increase in strength, our gains are essentially coming from two areas: growth and neurological efficiency. Growth can occur through an increase in size of the muscle fibers themselves (sarcomeric hypertrophy) which increases their actual contractile strength. Growth also occurs from the “swelling” effect within the muscle cell that comes from an increased capacity to store glycogen and water (sarcoplasmic hypertrophy). This can have an impact on strength mainly through creating more advantageous leverages around the joints. Either way – growth is driven by caloric excess. i.e. you have to eat a lot of food and specifically a lot of carbs. If you are trying to drop body fat you’ve got to create a caloric deficit and you probably have to restrict your carbs to some degree as well. Neither lends itself to an optimal environment for growth. Since we aren’t maximizing muscle growth and weight gain to drive progress on our lifts, we need to maximize the neurological side of things. We do this really in two main ways: train each lift heavy and train each lift often. The Heavy-Light-Medium template allows us to do both. On the standard Mon-Wed-Fri schedule we can train each lift directly up to 3 days per week. #2: Structured for Recovery Training each lift 3 days per week hard and heavy is not really feasible on a strong caloric deficit. If you are a natural trainee, you simply cannot recover from this amount of stress during the week. In fact, even in a caloric surplus, training each lift heavy 3 days per week is difficult, unless you are a rank novice in your first few months of training. However, with the Heavy-Light-Medium system two of the three training days are actually relatively easy. Even though they may not actually FEEL easy, trainees should never really be in danger of missing weights on Light and Medium training days. These days are not meant to impose new stress on the trainee – they are meant to preserve strength, facilitate active recovery, and keep motor pathways fresh while the trainee recovers from the stress created on the Heavy Day. This is in contrast to a much harder program such as the Texas Method. The Texas Method basically splits volume and intensity work up over the course of the week with a light day in between. So essentially you have a training week that is structured as Heavy-Light-Heavy as opposed to Heavy-Light-Medium. This can be difficult to navigate on a caloric deficit. This is also in contrast to body-part splits, which aren’t inherently bad, but are designed to maximize muscle growth by placing a high volume of work across all parts of the body with a combination of low-rep heavy training on the big lifts and higher rep isolation type work to maximize the “swelling effect” on each individual muscle group – usually with the expressed purpose of enhancing the physique. My very popular KSC Method for Power-Building program is structured like this and is very effective for gaining size and muscularity, but would not work well in a deep caloric deficit. It’s simply too much day to day stress and recovery would become a problem very quickly. #3: Only One High-Stress Day per Week Works Well With a Fat-Loss Diet The Heavy Day could also be re-named “High Stress Day.” So the heavy day really has to be the one day of the week where all the progress of the program is derived from. This means that both volume and intensity must be supplied in sufficient quantities that strength can be improved or at least maintained. If you are using the Heavy-Light-Medium system on a weight cut, you need to place your priority lifts on this day. The Heavy Day will be long and it will be hard. And we’re going to eat enough to train through it appropriately. Even on a weight-cut you can afford (and I actually recommend) at least one very high calorie/high carb day per week. We are going to use this high calorie/high carb day to get us through the Heavy Day workout. Many coaches recommend that you place the high calorie/high carb day on the same day as your hardest weekly workout. I actually feel that the better method is to place your high calorie/high carb day as the day before your hardest training day of the week. This is for two reasons. First is to leverage the “post cheat day bloat” and weight gain that occurs after a highcalorie/high carb or “cheat day.” If you’ve been dieting pretty hard on low-carbs/low-calorie for a week or more, and then all of a sudden you have an entire day of double, triple, or even more of increased carbs and increased overall caloric intake, it’s not uncommon to wake up the next morning 7-8 or even 10 lbs heavier than the day before. This is mostly all water weight or “bloat” but that bloat isn’t non-functional. It will improve your strength (if only temporary) and increase your energy reserves for a long hard Heavy Day workout. In my experience it takes a day for us to efficiently “uptake” or store all that excess glycogen and water so placing the cheat day or high calorie/high carb day BEFORE the Heavy Day only makes sense. Placing the high calorie day the same day as the Heavy Day workout is not efficient timing if you want to leverage all those increased calories towards a better workout. Second, when you’ve been eating low carb/low calorie for a week or so and all of a sudden you start gorging on high carb meals – energy drops as blood sugar spikes rapidly. This is the infamous “Carb Coma.” This is especially prevalent in natural fatties (or endomorphic body types) who tend to be more carb sensitive. And if you are on a severe weight cut – this is likely to be you. The “Carb-Coma” is not a productive state to train in. Energy is low, focus is off, and you generally feel heavy and sluggish. In my experience, the day AFTER the highcarb day is much more conducive to an energetic and focused training session. #4: Easy to Program Cardio in a Heavy-Light-Medium Program If you are trying to lose body fat, then diet alone may or may not be the only method that you use. For many of us, we can have a little more wiggle room in our diets if we institute 24 days per week of cardio work. The biggest problem many people have with cardio or conditioning is – when to perform it during the week? Depending on the nature of the cardio work performed, it can have a negative impact on a strength training session the following day. However, with Light and Medium days during the week, it’s okay if your legs are a little tired and beat up from the previous days conditioning work. You’re going lighter on your lifts so you can generally push through a little fatigue and it’s no big deal. The only day you should strictly avoid cardio work is the day PRIOR to your Heavy Day. However, if you are training Heavy-Light-Medium on MondayWednesday-Friday then it becomes very simple and easy to perform say 20-40 minutes of conditioning work on Tuesday-Thursday-Saturday without a huge drain on your strength work. It’s hard to do that on more demanding programs. #5: Adaptable to Any Individual As I mentioned before, the Heavy-Light-Medium template is extremely flexible. This is a big plus for a coach who has to program for a wide variety of trainees. Volume, Intensity, and exercise selection can all be tailored to the individual within this template. It can be used with a hard-charging 26 year old competitive power-lifter or a recreational 45 year old casual lifter, or even a 65 year old trainee with a few health problems. Simple manipulation of sets/reps/loads can make the template work for just about anyone. If you’re not sure on how to set up your own Heavy-Light-Medium program, I can probably get you set up on the right track with a simple 1-hour phone consult. All we need is your current numbers on each of the main lifts and then we can convert them all over to an easy to follow program that should yield a steady 12-16 weeks of progress. You can book a Phone Consult Here if you’d like some individualized help with this type of programming. Otherwise, do yourself a favor and review my Heavy-Light-Medium article series, read the Heavy-Light-Medium section in PPST3, or even review some of Bill Starr’s old programs, many of which followed this type of template. This should give you some insight on how to set one of these programs up for your own personal goals. Strength & Fat Loss: A Simple Formula Train on a Heavy Light Medium System When you are in the process of losing weight you need frequent exposure to the lifts. Your exposure to the lifts needs to keep pace with the weight loss so each time you hit a lift you aren't significantly lighter than the time before. You don't need a ton of per session volume, so maybe 4 work sets on Heavy Days, 2 work sets on Light Days, and 3 work sets on Medium Days. Try and keep your percentage offsets relatively small - about a 10% reduction in load on Light Days and maybe a 5% reduction in load on Medium Days. Squat on all 3 Days, Bench on Monday, Press on Wednesday, and do either Close Grip Bench or Paused Bench on Friday. Deadlift on Wednesday or Friday and perform Rows or Chins on the other two days. Have a Strategic Cheat Meal The night BEFORE your Heavy Day, have a higher carb, higher sodium cheat meal. This will fill up your glycogen stores and at some water weight before you do your Heavy Day on Monday. Squat and Bench heavy on Monday. A burger and fries (maybe 2 orders of fries!) and a regular coke is a good meal. Pancakes and Sausage is another good option the night before. Think starchy carbs and sodium! Don't Overcomplicate Macros Set protein up at 1 gram per pound of bodyweight each day. If you are over 25% body fat then you might scale that back to 3/4 gram of protein per pound of bodyweight. Carbs will be set at a HALF gram per pound of bodyweight and the adjusted after two weeks based on results. Add fat (but don't bother counting grams) via 1 higher fat protein meal as the last meal of the day (80/20 ground beef, whole eggs, or Salmon). Eat 5 Meals Per Day Divide protein up by 5 and eat that amount at each meal (ex: 225 lbs bodyweight / 5 = 45g per meal. Divide carbs up over the first 4 meals of the day (ex: 225 lbs bodyweight / 2 = 112g. 112 / 4 = 25-30g per meal) Meal 5 is a higher fat source of protein and green vegetables only. The first 4 meals of the day should be your carb serving and a LEAN source of protein from chicken, turkey, fish, egg whites, or protein powder. And So The Weight Cut Begins…….(Diet Plan) As much as I really don’t want to, I have made the decision to try and compete at 205 lbs at the meet in July. The lazier / hungrier side of me would rather compete at 230….which would mean just a 10 lb weight cut. 205 lbs means a 35 lb weight cut though…..ugh. As of now, I’m sitting at 240 which is just too much weight at my age and height. The decision is not necessarily a competitive one. Although at 5’4 – 5’5, I’m better suited to compete at 205 instead of 230, the real decision is based on my health and my energy levels. Now with 3 kids and a busy small business, the demands on my energy levels are ever increasing. I’ve been heavy and I’ve been light. There is no doubt that carrying around less weight means more energy and vitality. I know I’ll likely lose a little bit of strength in the process of dieting down 35 lbs, but I’ll deal with that when I get there. As of now, I don’t really have any target numbers for the meet. The primary purpose for me is to (1) Get me consistently training hard in the gym (2) Give me a target date for my weight loss goal. Or, like everyone else who tries to lose weight – it will become a distant mirage somewhere on the horizon – ill defined and impossible to grasp. The Diet Plan For now, I have set up 3 different plans: a low, medium, and high carbohydrate day. Protein is fixed at 250, and fat is minimal. No “added” fat to the diet plan, strictly what comes as a by-product through my meat selections. High and low carbs are always relative to the individual. I have done enough dieting to know what is high/low carb for my metabolism which happens to run quite slowly. Depending on how the weight loss goes I’ll rotate these 3 days appropriately over the course of the week, and will work in some strategic cheat meals as well. The overall strategy is quite simple. 5 meals per day Each meal with about 50 grams of protein per day. High carb days have 40-50g carbs at all 5 meals Low carb days have 40-50g carbs at meal 1 only Medium carb meals have 40-50g carbs at meal 1, 2, 3. Minimal fat, no oils, nuts, etc I’m not overly strict about weighing and measuring things out to be EXACT. I only count the macros from their primary source. In other words, I don’t worry about factoring in the protein from my oatmeal or the trace amounts of carbs from my whey shakes. And I count all veggies as free foods. The way I normally set the macros up is to set my protein right at my body weight, or just a little bit more. So at 240 lbs, 250 grams of protein will work. High carb days are generally about equal to the protein number or just a little under if you feel that body fat is really high. For those with a faster metabolism, I might set the high carb day up at say 100-200 grams more than their body weight, possibly even more. From there I just subtracted 100 grams for the medium day, and another 100 grams for the low day. If the high day was higher, say 400g, then I might subtract 150 g for the medium day, and another 150 g for the low day. Again, the faster the metabolism, the more carbs you get. This protocol has always worked for me and my clients, but as with any diet, sometimes you have to adjust based on the individual metabolism. Sunday was Day 1, and I started with the high carb day to give myself a little room to run. For the rest of this week, I have and am going to stick to just the low carb day to see how much weight I can shed right off the bat. After just one day of low carbs and a bunch of water I dropped 6 lbs. Down from 240 to 234. Here was the last two days: Sunday – High Carb 1 carton egg whites (50g pro) , 3/4 cup raw oats (measured dry) Protein Shake, 1 banana 6 oz chicken, 1/2 cup white rice (measured dry) Protein shake, 1 apple 6 oz chicken, 1/2 cup white rice Monday – Low carb 1 carton egg whites, 3/4 cup raw oats Protein Shake 6 oz chicken, vegetables (yuck) Protein shake 6 oz pulled pork Excited to keep it going! Conditioning The Necessity of Good Conditioning for Lifers Conditioning is one of those topics that raises a lot of debate in the strength training world – particularly for those who are not pursuing some sort of sport outside of the weight room. It’s pretty well accepted that if you participate in a traditional sport, there is a minimum degree of conditioning that must be maintained in order to practice and play your sport effectively. I hate the term “sport specific strength” because by and large it doesn’t exist. Yes, some sports require more or less upper body or lower body strength than others, but for the most part strength is strength, and it’s a general adaptation that carries over to any sport specific movement. Conditioning, however, is different. Conditioning is actually quite specific to time/duration, intensity/output, and modality. So cycling doesn’t necessarily prepare you well for running. And running doesn’t necessarily prepare you well for swimming. And long slow runs don’t prepare you well for high intensity sprint intervals. So this makes preparation of an athlete for their sport of choice relatively easy. A coach needs to examine the nature of the conditioning needed to practice/play a sport and match it as closely as possible in duration, intensity, and modality during the training program. This is most often necessary when working with athletes who have long offseasons where they may not be engaged in practice or play of their sport for long periods of time. In order to maintain some semblance of conditioning, we need to find a “proxy” conditioning routine to prevent the athlete from completely detraining. Keep in mind an important point – it is not necessary to maintain “peak” conditioning year round. Peak conditioning can be achieved in a relatively short period of time, provided the athlete doesn’t become completely detrained. A fundamental mistake many coaches make is trying to maintain peak conditioning year round, and this often comes at the expense of increasing strength, adding muscle mass, or letting the body heal up from chronic overuse injuries that are often the by-product of year round engagement of very high repetition movement (think running, swimming, cycling, throwing, etc). For some athletes who engage in their sport year round (often times to their detriment) it isn’t necessary to condition them at all outside of their practice environment. This would be the case for many swimmers and grapplers who never have much of an offseason, and whose conditioning demands are hard to replicate by anything other than practicing their sport. But the purpose of this article is not for the sport athlete – it’s for the lifter. This could be the competitive lifter, or simply for the guy in his garage who simply wants to get as big and strong as possible. Does this athlete need to condition at all, or should he simply lift and eat? If so, how much conditioning should he do and what should be the nature of his conditioning protocol? My opinion is, yes. Lifters will get better long term progress when they are conditioned. Now, before we go deeper into why I believe this to be true, let me first reassure all of you who absolutely abhor any type of cardio activity – I’m not going to recommend that you need to transform yourself into a hamster who spends an hour a day slaving away on a treadmill. We aren’t competitive bodybuilders and we don’t need single digit body fat levels and “razor abs” to be good lifters. We aren’t prepping for a 5-round UFC fight so we don’t even need our cardio to be that hard. You can get away with doing a little bit of moderate conditioning and have a tremendously positive impact on your strength training. So take a deep breath and take another bite of your cheeseburger. It’s not going to be that hard. 4 Reasons to Condition regularly…. #1: Tolerance for Volume If you want to get bigger and stronger you need to be able to perform and ever increasing amount of work under the barbell. I think most of us understand that moving from a 400 lb Squat to a 500 lb Squat takes more work than going from a 200 lb Squat to a 300 lb Squat. Whether you are a disciple of Westside Barbell or you prefer more traditional approaches (such as those in PPST3) there will always be a need to increase your training volume on the primary exercises. To what degree, how often, and exact set/rep arrangements will vary from lifter to lifter and program to program, but there is no way around training volume. You need to raise it over time. Whether its something old school like a ball busting 5×5 workout or a Dynamic Effort Squat session that includes 12 explosive doubles on a 1 minute rest….that shit is hard. It’ll challenge you physically, mentally, and even emotionally – but it needs to be a part of your training program somewhere if you are serious about getting big and strong. This type of work takes strength – duh. But there is also a conditioning element to these types of workouts. If you are out of shape it’s hard to complete them. It’s especially hard to complete them with serious weight on the bar, and without taking 15 minutes between sets. Real people have real lives and we don’t always have 2-3 hours of gym time to leisurely plod through our sets. So if you are out of shape you have two options – (1) take an exceedingly long period of time between your sets (2) do less work by either reducing load on the bar or reducing your volume. Well unfortunately option 1 isn’t practical or doable for most of us and option 2 won’t get you the results you are after. What if you just force the issue and dramatically reduce your rest time between sets? Maybe that works and maybe it doesn’t, but if you aren’t in condition enough to handle a reduced recovery period between sets your 5×5 workout is likely to become 5 x 5, 4, 3, 3, 2. That isn’t the same thing as 5 x 5. This is where conditioning comes into play. If we want to be able to keep handling heavy loads for high volumes with reasonable rest intervals between sets we need to be in shape to do so. And I think we need to get out from underneath the barbell to do so. So instead of just thinking about “training to get in shape” we need to reverse our thinking….”we need to get in shape to train!” And I really credit Louie Simmons for bringing this issue to the forefront of the strength training world. Louie is responsible for making sled dragging a staple of many powerlifters training regimens. At Westside Barbell, the Friday Volume Squat day is generally 10-12 explosive doubles, and there is some serious weight on the barbell for these workouts. Generally the lifters use 5060% of their 1RM plus about 25% of added band tension. For a Raw Lifter using straight weight (no bands or chains) this comes out to about 75-85% of their 1RM for 10-12 explosive doubles…..on very short rest intervals. And oh by the way, it’s expected that set 12 is just as fast (if not faster) than set 1. You have to be in shape to endure this type of volume at this pace. Don’t believe me? Try to do 85% of your 1RM for 10×2 with 1-2 minutes between sets. And stay explosive all the way through the 10th set. It’s a bitch. And you can’t do it if you aren’t in great shape. In order to keep his lifters and athletes in good enough shape to complete and progress on these types of workouts, Louie has his lifters regularly drag a sled for conditioning. As lifters build up their capacity on the sled (heavier loads, longer trips, shorter rest intervals, etc) their ability to handle the training volume improves. This doesn’t just apply to Westside Barbell. If you favor a more traditional volume protocol, say 5×5 with loads approximately 80% of 1RM (give or take a bit) you need to be in shape to complete those workouts as well….ideally with rest intervals under 10 minutes and form that doesn’t go all to hell on the 5th set. And what if you want to do something else after your 5×5 Squats? Can you, or is your gas tank so empty that you are just going through the motions on any other exercise performed that day? Ideally, after we squat we’d like to pull a few Deadlift sets, or some Cleans, or even Press or Bench Press. Do you have the work capacity to do so effectively. Even if you can, can you do it in a reasonable time frame? If not, you might consider raising your work capacity via some conditioning outside of the gym such as sled dragging or pushing a prowler. Science and Theory Muscular Tension Part 1 By Lyle McDonald Andy: “An absolutely fantastic article series by Lyle McDonald on muscular tension and its role in muscle hypertrophy. It’s a 3 part series, long but entertaining and informative. If you are interested in the relationship between strength / size this is a must read.” ------- While I’m waiting until I get the energy to get aggro again, and I will, I wanted to write about a topic I’ve been meaning to address for a while, a detailed look at the idea of muscular tension. What it is, why it’s important, how we can or cannot measure it and what confusion comes out of the concept in a practical sense. I’ve sure as hell typed up most of this in my Facebook group enough times to make this easier for me: I can type it up once and just link to it in the future. Honestly, that’s why I write most of what I write. Write it once, link to it forever after. Eventually, maybe put it in a book. This series will certainly be long enough. As well, this article is going to act as a background piece for some stuff I intend to write about going forwards regarding training, muscle growth and what the actual PRIMARY driver on growth is (hint: it’s still not volume). But since I’ll likely have several articles using this information, it’s faster and keeps the articles shorter to write it up once and link to it. Even if this thing got rapidly out of control. So with that short introduction, I want to look at the concept of muscular tension. What it is/represents, why it’s important to the training process and, perhaps more, err, importantly, how so many people completely misinterpret the concept in a real world training way. To address the latter, I’ll have to make a couple of digressions but, hey, let’s remember who I am and how I (over) write. And it will take multiple parts. How Muscles Work Ok, so picture one of your major muscles, pecs, biceps, quads whatever. The muscle has several components. At either end is the tendon which attaches the muscle to the bone. Tendons are just dense connective tissues although their density changes from the bone end to the muscle end getting less dense as you move away from the bone and towards the muscle. When the tendon meets the muscle, this is called the musculotendinous junction. Fun-fact: when people ‘tear’ a muscle, it is almost unheard of to tear the tendon from the bone because that connection is insanely strong. Rather, the relatively weaker musculotendinous junction is typically where the injury occurs: the muscle tears away from the tendon (rolling up like a window shade when a full tear occurs). So between the tendons is the muscle itself which is also made up of multiple components. This includes the myofibrils themselves, the actual contractile components of the muscle which generate force. There is also the sarcoplasmic component which is mostly everything else: fluid, enzymes, glycogen, everything that’s not the myofibrils for all practical purposes (as I wrote about a few weeks ago, despite years of debate, it’s now looking like the idea of sarcoplasmic hypertrophy is an actual phenomenon). There are also various connective tissues, titin, desmin and a host of others that connect the myofibrils in all sorts of complex ways. Some run along the muscle fibers, some connect the muscle fibers to one another in a grid, some connect it to the other parts of the cell. It’s just this interconnected lattice of stuff. Here’s a basic graphic showing how all of this works/fits together, linked from this page. So it’s time to generate force. The brain sends some signals, which move down the motor nerve until they reach the neuromuscular junction. Then a bunch of stuff happens causing muscles to contract, generating force to (hopefully) accomplish whatever is being attempted. I’ll discuss some of the details of this in a bit. As I’ve discussed previously, there are a fairly large number of factors that can influence on the actual force produced. The big one of relevance here is the physiological cross sectional area of the muscle or muscle fibers. So imagine you took a cucumber and cut it down the middle top to bottom so you’re looking at the round end. That diameter allows you to calculate the cross sectional area. If you cut a muscle in the same fashion, that distance across would be the same thing essentially. I said ESSENTIALLY. And the amount of force a muscle can generate is related to this measure times what is called specific tension. Specific tension is the amount of force per unit cross sectional area that can be generated. The Initiator of Muscle Growth For decades it was stated that “We don’t really know what makes muscle grow” and this assertion was used to defend the absolutely goofiest bullshit training approaches that you can imagine. If you can’t say what generates growth, then any training system you can dream up is fair game so long as it “works” or at least seems to. It didn’t help that so many things seemed to work. Well, especially once steroids got into the game and literally anything did work because steroids build muscle without training to begin with. Any stupid shit you do in the gym works so long as your dose is high enough (the main volume component of training is volume of gear used). Hence any stupid shit got defended for training because we supposedly didn’t know what triggered the process of muscle growth. This isn’t to say that a variety of theories weren’t thrown out over the years. The most common and still believed to this day was probably the idea that training breaks down muscle which is then built back up to higher levels. This was based on the almost wholly incorrect idea of supercompensation but that’s another topic for another day. It also doesn’t work that way in the least. It was also related to the idea that muscle damage per se was a stimulus for growth (why so many people continue to chase DOMS/soreness) although that’s mostly thought to be incorrect. Many types of training stimulate growth with no damage and if anything, muscle damage may be detrimental to growth. This tied in somewhat with an energetic theory of growth, the idea that training reduce skeletal muscle energetic status (i.e. ATP/CP) which somehow triggered growth. In my first book The Ketogenic Diet, I wrote about a then highly regarded theory that training would cause a depletion of ATP in the muscle causing it to reach ‘rigor’ and lock-up with the subsequent lowering causing the damage that turned on growth. Dan Duchaine’s Bodycontract training system (something that probably 3 people reading this will remember) was based around this: a set of 8-12 to failure to deplete ATP and then 3 heavier eccentric reps to cause targeted muscle damage after the muscle fibers had hit rigor (he called it ‘targeted intensity’). I doubt this model in fashion anymore given that muscle damage doesn’t seem to be a big player in growth overall. I certainly haven’t seen it discussed in a lot of years and I wouldn’t argue nor defend it 20 years later. Mind you, it has elements of the actual picture but isn’t entirely correct. There were ideas related to ischemia/hypoxia (basically low blood flow/Oxygen) which were dismissed for years but may have some merit when you consider some of the blood flow restriction work (BFR). I’ll be writing up another longwinded article on this but short version: hypoxia would appear to be an indirect contributor to growth in that it helps the body to recruit more muscle fibers. Others felt that flooding the muscle with blood was the key: the pump theory of growth, essentially. This might actually have some validity if you’re on steroids to keep the drugs within the muscle longer so that they bind to the receptors longer. Maybe. But big picture the pump doesn’t seem to mean very much. Humorously, others felt that keeping blood moving through the body was the key, hence the PHA training system (that maybe 2 people reading this remember). There’s also been some theorizing about cell swelling for over a decade now but I haven’t seen anything particularly convincing in that regards (most of the research seemed to be in liver cells under non-physiological conditions such as saline infusion and such). I’m not saying it doesn’t play some role. I’m saying I’m not convinced it’s that big of a deal in the big picture under normal conditions. I could be wrong. If this were a thing in muscle, pump training might play a role in that it could conceivably cause cell swelling. A super goofy study came out recently using ‘sarcoplasmic specific’ training protocols that generated immense increases in muscle thickness immediately after training due to fluid shifts. But you wanna look good in the club for a few hours, this is your jam. Go get your pump on and then go get your drink on and you might get lucky. Perhaps Arnold was right. Currently there is interest in the metabolite theory of growth although, as I’ll write about eventually, it’s unlikely to have much merit (I’ll address it briefly in Part 2 or 3 of this series) in terms of metabolites directly stimulating growth. Like hypoxia, accumulating metabolites probably just help to recruit the highest threshold muscle fibers at the end of a set (this will make sense when I explain the process below). Don’t get hung up on this right now, I have a tediously long article coming later. Then there was the hormonal response theory, that the testosterone or growth hormone response to training, was important. And, pretty much it’s not with any effect being extremely minimal since those small spikes in hormones just don’t amount to much. At best it plays a very minor role; at worst it is 100% irrelevant. Sure, injecting supraphysiological levels of drugs matters. Spiking testosterone or growth hormone for 15 minutes not so much. The growth response to training is almost purely local. The one I’ll mention last, because it was probably the closest to right, was proposed by Vladimir Zatsiorky. He pointed out that during any given set, a certain number of muscle fibers would be recruited to generate force. But that recruitment per se wasn’t sufficient. Rather, those fibers had to be fatigued as well (this was based on the idea that fatigue of a fiber per se triggered growth which isn’t quite right). Basically you had to recruit the fiber (unrecruited fibers aren’t trained) but you also had to subject it to sufficient work to cause it to adapt. So with all of those theories floating around, it seems easy to understand why people would argue that “We don’t know what causes muscle growth.” Tension/Mechano Sensors As it turned out, the idea that “We don’t know what causes muscle growth” was wrong to begin with. As early as 1975, researchers had the picture about 90% worked out and it had been established that the primary initiating factor for growth in adult skeletal muscle was the exposure of muscle fibers to high levels of tension with the researchers concluding: It is suggested that increased tension development (either passive or active) is the critical event in initiating compensatory growth. Yet people maintained that “We don’t even know what causes growth” for decades afterwards. Well, I’m sure they didn’t know. But physiologists sure as hell did. Or had enough of a model, that would then be shown to be more or less correct. Now tension can be generated in different ways and you will read about active vs. passive tension. I’m not getting into this in any detail but passive tension are things like those goofy ass studies where they tie a weight to a quail’s wing for 30 days. The chronic weighted stretch exposes the muscles to passive tension overload and causes rapid growth along with an increase in muscle fiber number (hyperplasia) This doesn’t work in humans, by the way. Active tension is what we are interested in, when a muscle is forced to actively generate force. One nifty way they create increased active tension in animals is through what is called the synergist ablation model. This is a nice way of saying that they cut one of the muscles (the synergist) that supports a joint. This causes the remaining muscle to be overloaded to an insane degree overnight. And growth is absurdly fast and potent. It’s like 50% in a matter of days in animals or something (don’t swear me to that number). So in a human it would be like cutting the soleus so that the gastrocnemius has to take over. Suddenly the gastroc exposed to an enormous overload since it has to take over for the cut muscle. It might be the the only way for some people to get calves. I am joking by the way. I think. But let’s move to something a bit more physiological as an example of active tension. For example, lifting a weight where muscle fibers must generate force to perform the movement. This requires them to generate/exposes them to high tension which, as above, is the initiating factor in muscle growth. Like I said, we knew this in 1975. Or at least had an inkling that this was the case. And it turns out to absolutely be the case (literally any review paper you read on mechanisms of hypertrophy regardless of the author or their bias will list tension as the primary factor in initiating growth). What we didn’t know up until fairly recently (by which I mean like 15 years ago or so) were the actual biomchemical pathways that were involved in turning on protein synthesis. And we now know that the primary mediating factor for muscle growth is something called mTOR (the mammalian target of rapamyacin). Training activates mTOR and so do amino acids, especially leucine which is where the whole BCAA thing comes from (they are still garbage, for the record). Yes, there are other pathways and factors involved such as AKT and ribosomal activity and many others but mTOR is kind of the key or final pathway. If you block mTOR (with rapamyacin), protein synthesis from training is blocked no matter what else you do. You can think of mTOR as sort of the final pathway for all of this stuff. What was missing for a while was how the first achieved the second. That is, how was a purely mechanical signal (muscle tension/mechanical work) being translated into a chemical/biological signal? Because at some level, this didn’t make much sense. How can a mechanical process activate a biological one? What did make sense was that some biological change in the muscle, ATP or lactate or hormones or whatever was causing it that it was related because it makes sense for one biological change to trigger another. This was clearly a case of a mechanical effect causing a biochemical pathway to activate. What was going on? Bioengineers to the Rescue As I originally heard the story, the muscle physiologists couldn’t get anywhere with this and got some bioengineers to come take a fresh look at the problem. This was kind of before all of that other connective tissue stuff like desmin and titin I mentioned above were known about mind you. The idea that muscle fibers were connected to other parts of cell wasn’t a thing at the time . You just had muscle fibers kind of running down the length of the muscle with tendons on the end and when they contracted, movement occurred around the joint they were attached to. And somehow that could turn on this biological growth process. And supposedly the bioengineers were like “Ok, so if you had some sort of tissue that connected the actual muscle fibers (running lengthwise down the fiber) to other structures in the cell, that could explain how a mechanical signal turns into a biological signal. The fiber contraction would pull on those other tissues which alters cell structure and could translate into a biological signal.” This would provide a mechanism for mechanical tension to turn on a biochemical cascade. And I’m sure the muscle physiologists were like “Lol, ok” and then looked for these supposed structures and were like “WTF, they were right” or something. And then probably took credit for the idea when it was all said and done. Now I may have dreamt all of the above up (it wouldn’t be the first time) but, even if I did, it turns out that this is exactly what is going on. Essentially, there are mechanosensors within skeletal muscle that, when activated, transform a purely mechanical signal (muscle fibers generating/being exposed to high tension loads) into a biological one, the activation of mTOR. Note: I don’t know exactly when the above model became a thing but it was somewhere between 1993 when I graduated from UCLA and the early 2000’s when I took an advanced exercise physiology class at UT Austin. So what are the mechanosensors? So far as I can tell, they are currently calling these things Focal Adhesion Kinase which, when they do their magic, activates mTOR (this appears to be mediated through the generation of phosphatidic acid which is why those supplements were popular a while back). Going forwards I’ll just abbreviate this process as FAK/PA/mTOR. Boom, a mechanical signal is converted into a biological one. Tension overload activates mTOR and growth is stimulated. Problem solved. Note: Other systems have this too. Bone is an interesting one where high force impact loading activates mechanosensors called osteocytes within the bone that turn on the process of increasing bone mineral density as an adaptive response. Even more interesting, after some number of high force stimuli, the osteocytes become refractory to further stimulation. That is, there is a per workout or per day maximum to the stimulus. Hmm, that sounds familiar. Even the cell swelling theory is thought to work through physical stretching of the cell where the mechanical stretch turns on biological processes even if I remain unconvinced that it’s a major pathway in skeletal muscle growth. But, fundamentally it’s mechanosensors all the way down. And, once again, that is the primary initiating event in turning on hypertrophy: high tension forces generate a biochemical cascade that turns on protein synthesis. Yes, there are other players in this process but this is the key one. Importantly, it looks like there need to be a sufficient number of high-tension contractions for this to occur. It’s not just a function of exposing a muscle to a singular brief high tension load. You have to do it a number of times for the mTOR cascade to get activated. But at this point nobody knows how many contractions are required on either a per set or per workout level (though it’s funny that everything seems to be coming back to Wernbom’s recommendations from 12 years ago and it won’t surprise me in the least if he was right all along). A single maximum daily contraction doesn’t turn on growth and a group that did 5 maximum single reps twice/week showed no growth so there’s clearly more to it than just high tension. Some volume of high-tension contractions is required (and nobody including me has ever said differently, that volume doesn’t matter. I’ve said that it wasn’t PRIMARY because it isn’t). Put more succinctly. High muscular tension is REQUIRED but not SUFFICIENT to stimulate growth. Without a high tension stimulus, growth isn’t turned on (and note that I didn’t say high LOADS, I said high TENSION which I’ll explain later). But other factors play a secondary role to the presence of mechanical tension. Volume is one of them. You need some amount of contractions under high tension conditions to turn on growth. We just don’t know how many yet. Which is basically what the Zatsiorsky model of growth I described above is getting at. He put it in terms of recruitment and fatigue which is wrong but his general picture was still right. Just making a fiber generate high tension isn’t sufficient to trigger growth. Some number of contractions is also required to activate the FAK/PA/mTOR cascade. High tension is still the key which is why running and other low intensity activities don’t generate muscle gains. Ok, that’s not true, they do in total beginners where even that low intensity activity probably is a tension overload for a little while. Then again, so is Wiifit at that level. But beyond a certain point, those activities do not increase muscle mass. I’ll address the low-load/BFR stuff, which seems to contradict this (except that it really doesn’t), briefly later in the series and in excruciating detail eventually. So we ask: how do we generate high tension in a muscle? Now I have to digress into some details. Recruitment and Rate Coding Fundamentally there are two ways that the body can get muscles to generate force. The first is through recruitment, actually making the muscle fibers themselves activate to generate force. The second is through rate coding, the rate at which signals are sent down the motor nerves to those fibers which impacts on how they fire. The combination of the two determines the force output of the muscle and the body has different “strategies” for using one or the other depending on the situation (and this gets insanely complex and I am so not going to try to get into it because it’s not big picture relevant). I should that there are two primary types of muscle fibers, Type I (slow twitch, oxidative) and Type II (fast twitch, glycolytic). There are also a bunch of sub-fiber types like IIa, IIx, IIax and some hybrids but I’m going to ignore the details here since they aren’t really important. I’m just going to pretend that there are Type I and Type II to keep it simpler. Type I are typically smaller, contract slightly less quickly, generate less force, are more aerobic and fatigue very slowly. They are good for endurance activities. Type II are typically larger, contract a bit more quickly, generate more force, are more glycolytic and fatigue more quickly. They are better for high-intensity activities. Type II fibers generally have more potential for growth as well. During activities, muscle fibers are recruited in a fairly orderly way from smaller (Type I) to larger (Type II) depending on force requirements according to what is called Henemman’s Size Principle (not to be confused with Henneman’s Wife’s Size Absolutely Matters Principle). So Type I are recruited first, with Type II coming in later progressively. And there is a continuum of both types of fibers with a continuum of characteristics that will come in progressively as the intensity of activity goes up. It’s also way more complex than this, don’t worry about it. At around 20% of maximum force, basically lower intensity aerobic work, only Type I fibers are needed. This is why it can be continued for extended periods: Type I fibers are highly aerobic and don’t generate many waste products. You can go until you get bored or dehydrated. I mean, ultra-endurance “runners”, who may be going 3.5-4 mph (a brisk walk) will cover hundreds of miles at that pace. It’s all Type I fibers at this level. As force requirements go up, Type II fibers will be recruited to a greater and greater degree. So you move to faster running and start to recruit some Type II fibers. Now Type II can still be somewhat aerobic, especially at this level. So you still don’t fatigue particularly rapidly. Forever maybe become 6 hours on the bike or when glycogen runs out. Now you’re running near your maximum sustainable speed, something you could do for an hour. Lots of Type II fiber recruitment. Not all of them, but more. There’s waste products being generated but they are not accumulating. It hurts but you can keep going. Then you go all out sprinting, HIIT type. Depending on the intensity you probably get damn close to full recruitment. Waste products build up rapidly and you fatigue in 45 or 90 seconds. And that’s how fiber recruitment basically works, at low intensities the body only needs lowthreshold Type I fibers with higher threshold fibers being recruited progressively with increasing intensity. At least up to the point where full recruitment occurs. What is that point? In a weight training sense, maximum recruitment occurs at about 8085% of MVIC (maximal voluntary isometric contraction which I will roughly take to be synonymous with 1 repetition max even if it’s not exactly the same). At that level, all muscle fibers are recruited. Beyond this point, the body generates more force with rate coding and other complex neural stuff as there are no further fibers to be activated. A quick note: there is a long held-belief that the body can only recruit a small portion of available muscle fibers but this is fundamentally wrong. Using a technique called the Interpolated Twitch Technique (ITT), it’s been found the people can recruit 98-99% of their biceps fibers. In contrast, they can only recruit 88-90% of their quadriceps muscle fibers (low back is down at 75% if I recall correctly and I suspect this is to protect spinal disks). This leads me to speculate that the “empirically observed” and “semi-research suggested” idea that legs need more volume than upper body might be related to this. If even during a hard set you can’t get full activation of your quads/legs, you might need more total volume to get the same overall growth stimulus. We really need more structured and systematic work on this. In any case, this recruitment threshold of about 80-85% 1RM (and some put it closer to 90%) has a couple of implications. The first is that beyond about a 5-8RM you don’t get any more fiber recruitment. Doing a 3RM or 1RM won’t recruit any more fibers than a 58RM. You’ll certainly see different neural patterns, rate coding and such. But from a fiber recruitment standpoint there is no real difference and going heavier beyond a certain point won’t lead to further recruitment. I’ll come back to the other implication later down. Fun fact: The above only holds for large muscles like arms, quads, pecs, the ones we care about. In smaller muscles like the eyes and fingers, recruitment occurs up to about 50-60% of max with rate coding dominating after that. This provides much finer muscle control; if it didn’t work that way, your eyes would fly back and forth as you tried to read this and you’d have no control over your fingers for fine motor tasks. This is also why all those finger and thumb muscle strength or endurance studies have less than zero relevance to training (and why citing them to make any argument about real-world weight training is not only pointless but shows a lack of basic physiology knowledge by the person doing it). They simply don’t apply. Ok, so that’s recruitment and rate coding and implies that getting full recruitment of a muscle means training at 80-85% or heavier. Except that that isn’t correct. Two Ways to High Tension So if you start at 80-85% of MVIC, maybe a 5-8 RM you get full recruitment from repetition 1 and throughout the entire set and I’ve written previously that if you had to pick a single repetition range for growth, this is it. I based the argument on optimizing both recruitment and total mechanical work. Because working in this range will cause full fiber recruitment from the first repetition and allow you to perform the most repetitions under that condition compared to either heavier or lighter sets. Knowing that we need fiber recruitment and some number of contractions this would arguably be the most efficient way of achieving that. In any case, if you do a 5RM you’ll get 5 total reps at full recruitment. If you do 3 reps with 5RM you get 3 reps with full recruitment. Of course, you can probably do more sets of 3 at a 5RM than sets of 5 at a 5RM and might get more total per workout contractions. Those sets of 3 will be a higher quality technically or in terms of bar speed as well. So you can do 5 sets of 3 with 5RM for 15 effective reps versus perhaps 2 sets of 5RM for only 10 and with better technique and speed. This is how strength/power athletes typically train, using a heavy load but not taking it to failure so that more total high-quality sets can be done. The same principle can hold for hypertrophy but let’s move on. But now lets ask the question what the process of fiber recruitment looks like if we start below 80-85% of max. So let’s say we’re lifting at 70% of max, maybe a 12-15RM on average. Now, by definition, the body doesn’t need to recruit all muscle fibers in this situation since force requirements can be met by less than 100% fiber recruitment. For some number of reps in the set, full recruitment will not be achieved since it’s not needed. But as the set continues, some of the initially recruited fibers will start to fatigue. When that occurs, the body will recruit higher threshold fibers to maintain force output and continue the set. And more fatigue will occur. And more fibers will be recruited. And this will occur until, at some point in the set, full recruitment of all available fibers has occurred. And that full recruitment will be maintained until the set is terminated either because the lifter stops or muscular failure occurs (defined here as the repetition not being completed no matter how much force the lifter exerts). So, hypothetically, say you start lifting at 75% of max, about a 10-12RM or so. For the first 5-6 reps you won’t reach full recruitment as the body can generate enough force without needing all muscle fibers to contribute. As fibers fatigue, the body will recruit more fibers and over perhaps the last 3-5 reps (or whatever number) you will get full recruitment. Which means that it’s only over those last 3-5 reps that the highest threshold/Type II fibers are being recruited, hence exposed to high tension, and doing mechanical work and hopefully activating the FAK/PA/mTOR cascade. Which raises the question of when in the set do all fibers reach full recruitment. I am aware of two studies on the topic. In one study, trained men performed a set to failure in the leg press at either 90% or 70% of 1RM with surface EMG (admittedly limited as a methodology) being used to determine activation. On average, the subjects got 8 reps at 90% and 18 reps at 70%. Without getting into the weeds on what they measured (it was a bunch of peak and average EMG), what the study ultimately found was that the peak EMG at 70% was the same when compared to the “matched repetitions” of the 90% set. Which is a weird way of saying that the peak EMG was the same for the final 8 reps of the 18 rep set as for the 8 reps of the 8 rep set. Either way you get 8 repetitions with full recruitment. You just have to do 10 non-full recruitment reps first with the lighter weight to get those same 8 full recruitment reps. A similar study in untrained women using rubber tubing found the same thing. It looked at trap activation during a lateral raise at either a 3RM or 15RM set. And what it found was that full activation was reached from the first rep in the 3RM set as would be expected. But full recruitment was not reached until the last 3-5 reps in the 15RM set. So in the 3RM set, 3 total reps were done under full activation, in the 15RM, 3-5 reps at full activation were done. Both groups got essentially the same number of full recruitment reps. The 15RM subjects just had to do 10-12 reps without full activation to get there. And I do wish they’d stop using such extremes, comparing perhaps 85% to 75% or whatever to see how it differs. What you see is that submaximal loads lifted close or to failure can cause similar fiber recruitment patterns as heavy sets. I’d note and I’ll come back to this in a later part of the series that this is how low-load/BFR training essentially works. By taking a low-load set to failure (and this doesn’t happen if you stop short of failure which is a big pointer in to what’s going on), you reach or achieve full muscular activation near the end of the set. In a conceptual sense, you sort of have to by definition since failure is 100% regardless of how you get there. A 5RM is 100% effort at the end but so is a 30RM so long as both are to true failure. So the fiber recruitment patterns would be expected to be at least similar. And they basically are. The same occurs with BFR with the metabolites/hypoxia helping with fiber recruitment. Simply, they increase high threshold fiber recriutment even with the submaximal loads. At the end of each set the highest threshold fibers are recruited and exposed to a tension stimulus for a sufficient number of contractions. Yadda yadda, FAK/PA/mTOR cascade. Mind you, you have to do 25-30 painful, pointless reps first to get to full recruitment and tension but that’s what’s happening. But it sure looks edgy on Instagram and isn’t that what training is all about? Put more simply, whether you do a set of 3-8 with 80-90% 1RM, a set of 15RM with 70% 1RM or a set of 30 with 25% 1RM (or BFR it), you end up getting some number of repetitions under full recruitment and high tension. In the first case it’s from the first repetition and you get 3-8 reps under full recruitment. In the second full recruitment occurs around reps 10-12 and you get 3-5 reps under full recruitment, in the third case, you waste your life doing 25 worthless reps to get to the 5 or so good ones or however many it is. But it’s all ultimately a path to high tension overload of the high threshold muscle fibers (yes, there is some speculation that low load/BFR may target Type I and this is assuredly a durational/fatigue issue that I’m not getting into here). As I wrote on Facebook the other day: All roads lead to high tension. It’s just a matter of how you get there. Effective Reps While I’m on the topic I might as well address a relatively new concept which is that of “effective reps”. The idea here is that it’s only those repetitions of a set done under full (or near full) activation that “matter” in terms of the growth stimulus. The total sets don’t matter. The total reps don’t matter. It’s the effective reps that matter. I don’t know that I’d argue this in the strictest sense although it’s certainly true if you’re talking about the highest threshold muscle fibers. Clearly fibers are being recruited or trained without full activation. Just not all of them. If you did a 5RM set, that’s 5 effective reps since they were all done under conditions of full recruitment. So if you do a set of 12 near failure and get full activation for reps 10 through 12, that’s 3 effective reps. If you do a set of 35 reps with 30% of your 1RM, you just fucked around for ~30 reps to get to the 3-5 or so effective reps. The end result is effectively the same. Get it? Effectively? Effective reps? Effectively? Nevermind. Now we still don’t know how many effective reps are necessary to optimally activate the FAK/PA/mTOR pathway. Once we do, and if we also find out that it saturates at a certain point on a per workout or per week level we’ll be able to end this fucking volume debate once and for all. So if we determine that 20 or 40 effective reps per workout or whatever (or so many contractions per week) is optimal and/or the limit to the growth stimulus, we have the basic answer of how to optimize training for growth. I still suspect Wernbom’s earlier data will turn out to be roughly correct. Because we know that there are different ways to get the same number of effective reps. So consider someone doing multiple straight sets of 8 say 4X8 on a 2′ rest. Let’s say they start 2 reps in reserve/reps to failure, so it’s a 10RM load. Realistically, the first set might get a couple of effective reps under full fiber recruitment. With each successive set, assuming the rest interval isn’t too long to allow full recovery, as fatigue accumulates and the set gets closer to failure the number of full recruitment reps per set will increase. Becuase what will happen is that set 1 is at 2RIR and set 2 is at 1-2 RIR and set 3 is at 1RIR and set 4 is 0 RIR. So on set 1 maybe it’s 1-2 effective reps, on set 2 it’s 2-3, on set 3 it’s 4 and on set 4 it’s also 4. What’s that, 11-13 total effective reps across the 4 sets. Do it for a second exercise and maybe you double that to about 20-26 effective reps or whatever it works out to. So that’s one way to do it: some number of straight sets with an incomplete recovery that results in an accumulating number of effectivee reps per set over the workout as full recruitment starts earlier in each set. Or consider the various rest-pause approaches such as Myo-Reps or Doggcrapp (or simply rest-pause). Here you start with a heavy set, often called an activation set. The idea is to either start heavy enough (i.e. with an 8RM which is about 80% of max) or get close enough to failure with a submax weight to get full fiber activation in that first set. So you get to rep 8 with maybe 2-3 full activation reps and stop the main set set (Myo-reps used to use speed cutoffs, DC went to failure). Now rest 15 seconds, long enough to recover a bit but not completely. Now you get 2-3 more reps which are probably also still under full activation so they count as effective reps (and they do that without requiring another 5 reps of a straight set). Rest 15″ and you get 1-2 more. Rest 15″ and you get 1 more. So maybe it’s 8-9 effective reps across that singular rest-pause set. If you do two of those sets you get 16-18 total effective reps which is about the same as the straight sets although it only took you two rest-pause sets versus 8 straight sets to do it. Is this making sense? The corollary to this is that sets that are too light AND nowhere close to fatigue, may not contain any effective repetitions, or certainly not many (or certainly not effective reps for the highest threshold muscle fibers). If you do a set of 6 with a 12RM, you’re not recruiting the highest threshold Type II fibers at all. Not unless you do repeat sets with a short rest interval so that there is cumulative fatigue across the sets. So if you do 6 sets of 6 reps with your 12RM but only rest 15-30 seconds between sets, fatigue will accumulate and you’ll reach full recruitment eventually. Maybe by the fourth set you’re getting some effective reps or whatever and that increases with each subsequent sets. It “works” although you basically fucked around for the first 3 sets to even get close to a meaningful training stimulus. As I think about it, Gironda’s 8X8 probably worked by this mechanism. It was an honest workout. In this vein, there is a recent super stupid study that looked at what they called the the 3/7 method. Using untrained subjects, it compared a single set of 3,4,5,6 and then 7 repetitions at 70% of max (12RM) with like 15″ rest between mini-sets to a group doing 8 sets of 6 with 12RM. And the 3/7 method worked better than the straight sets (inasmuch as more or less everything works on beginners). Because with that short rest, it probably got at least some effective reps near the end despite being pathetically submaximum. In contrast, 8 sets of 6 at 12RM is a series of warm-up sets and I bet they were lucky to get even a few full recruitment reps during that workout. I made similar comments about the Haun et al. study Mike Israetel was involved with. It used repeat sets of 10 at 60% of max with the subjects reporting 4 reps in reserve. So it was 4 reps from failure and there was an 8-10′ rest interval due to the goofy nature of the workout setup. So there was no cumulative fatigue (RIR stayed at 4 across the workouts and study). If I’m being generous let’s say each of those warmup sets got maybe 1 effective rep per set. Maybe it’s 2. Don’t believe me? Go back to that 15RM study I described above. Full recruitment didn’t occur until rep 9-12. 10 reps with a 14RM load and you maybe get full recruitment on rep 9. 8 if you’re lucky. 1-2 effective reps per set at best. First let’s compare a workout with 1 effective rep per set to a real workout. At 10 sets/week that’s 10 effective reps per week. NOT per workout. PER WEEK. You can achieve the same thing with 2 all out sets of 5RM. Go to 20 sets per week and that’s 20 effective reps per week. 4 sets of 5RM per week. At 32 sets/week maybe they got 32 effective reps. I can do that in 4 all out sets of 8 in a single workout. I could also do 2 sets of 8RM twice/week and go home. In those 4 sets I might accomplish the same number of effective reps as 32 piss-ass sets. I’ve done 32 effective reps in 32 reps vs. 32 effective reps in 320 reps. 1/10th the volume by reps and 1/8th by sets. If I go nuts and double my workout to 4 sets of 8RM twice/week, I’ve gotten 64 effective reps in those 8 sets. I’ve done 64 reps in 8 sets versus 320 reps in 32 sets for TWICE the effective reps. And that’s without spending 2 hours in the gym fucking about. Even if you give the benefit of the doubt and say the 10 reps at 4RIR gave 2 effective reps per set, 32 sets is 64 effective reps PER WEEK. If I train a muscle group for 4 sets of 8 to failure twice a week I achieve the same thing. 8 sets for 64 total/64 effective repetitions vs. 32 sets and 320 reps for the same 64 repetitions. And I get to do it without having to live in the gym fucking around warming up for 2 hours. Basically the workout in Haun et al. was a lot of pissing around. And maybe that’s why it needed such ludicrous volumes to accomplish anything at all. The sets were so piss-ass low intensity, low fatigue that almost none of the reps were an actual stimulus to the muscle fibers. These are warm-up sets at the rate of 6-7 sets per muscle PER HOUR. You could do that all day long until you went nuts from boredom. Seriously. The fact that the growth appears to have been predominantly sarcoplasmic speaks to that. Actual myofibrillar protein synthesis wouldn’t be turned on if there aren’t enough high-tension reps to activate the FAK/PA/mTOR pathway. But you get a lot of volume and stress sarcoplasmic components with that kind of ineffective training. And if that’s your goal, go to town. Or just learn to train for real. Because contrast that to the Barbalho papers on women and men where all sets were truly taken to failure and where the low volumes did just as well if not better than the higher volumes. Because in every set that was done, a large number of the reps were done under full recruitment and were effective reps. When they were doing 4 sets of 4-6RM in that week that’s 16-24 effective reps per workout because every rep was done under full recruitment from rep 1 until the end of the set. And that was true of every week since they were true RM loads (I still do not believe the squat workouts were achievable, mind you). It would take 16-24 sets of piss-ass low intensity work getting 1 effective rep per set to accomplish the same stimulus or 8-12 if you got 2 effective reps. So 1/2-1/4th the volume if you actually train hard. And no I’m not saying you need to train to failure. I’m making a point about how different approaches to training can generate vastly different numbers of ‘full recruitment/effective reps’ per set, workout or per week. You can do way more sets but if they are ineffective in terms of not achieving full recruitment for sufficient tension overload, they may still work worse (or certainly no better) than a lower number of sets that are actually challenging. And that alone might explain all of the volume debate or the discrepancies in the studies (which really don’t exist as currently 6 of 8 studies show the same thing with one shit show and one outlier people refuse to discount). Because studies that use lower volumes of actually intense work (you know, all the ones supporting low to moderate volumes which represent 6 out of 8) are getting plenty of effective reps with a low volume of training. And if there is a per workout saturation point, higher volumes shouldn’t work better. And, in contrast, those that are using piss-ass intensities are not. They only appear to ‘need’ such high volumes because the workouts are so ineffectually designed. You know, like a workout where supposedly guys did 5 sets of 8-12RM on 90 seconds in the squat or bench which is utterly impossible (PROVE ME WRONG, FOLKS). Which would ONLY be remotely achievable if “failure” were defined as about 4-5 reps before actual failure. Which if I don’t miss my guess is exactly what happened in that particular study (I would love to see video of even one of the workouts). Because the workout is simply impossible to do once much less 3X/week for 8 weeks if the sets are anywhere close to failure. They can’t have been close to failure becuse the workout would be impossible at the higher volumes. Mind you, it’s not as if the statistics supported the highest volumes anyhow but I digress. Because in 5 truly hard sets with a sufficient rest interval, you can readily achieve the same number of effective reps as 15 piss-ass intensity sets with a stupid workout design. You may only ‘need’ high volumes if you simply don’t, can’t or won’t train with any degree of intensity. And that’s probably exactly what is the case. All those bros in the gym doing 20 sets/muscle group who get “big”. Well it’s probably taking them those 20 sets to get an effective stimulus as someone doing 4-6 hard sets. Which is what I’ve said before: If you think you NEED 70 sets/week for a muscle, you don’t know how to fucking train with any sort of intensity or focus. Visit me in Austin and I’ll prove it to you. Summing Up Muscle Tension: Part 1 Ok, so this already got away from me and it’ll probably go 4 parts to address this all. The basic gist of Part 1 is this. High muscular tension is, without debate, the primary initiating factor in muscle growth and we’ve known this since the 70’s. And every review paper regardless of author or their personal bias or online bullshit states this. This occurs through mechanosensors, probably Focal Adhesion Kinase which translate a mechanical stimulus (high tension in muscle fibers) into a biochemical cascade involving mTOR. Tension alone is required but insufficient. Some number of high tension contractions is required to turn on this cascade but we don’t know how many in either a per set, per workout or per week fashion. What this means is that the process of turning on growth means 1) recruiting the highthreshold/Type II muscle fibers and 2) exposing them to sufficient amounts of mechanical work to turn on this cascade. Towards that I examined how fibers are recruited in response to force requirements. The take-home is that you can get full recruitment with heavy loads of 80-85% of max or so or by taking lighter loads near or to failure. With lighter loads, as fatigue sets in, the body will progressive recruit higher threshold fibers, eventually reaching full recruitment at some point late in the set. Both ultimately end up causing recruitment of muscle fibers, exposing them to a high tension load. A heavy set of 5 and a set of 30 taken to failure probably both get about 5 full recruitment reps. The 30 reps to failure just made you do 25 pointless reps to get there. This led into a discussion of the idea of effective reps, those reps in a given set or workout that are done under full recruitment/high tension conditions which, as noted can be achieved in different ways. Straight sets at a low RIR/RTF is one way, rest-pause is another. There are also stupidly ineffective ways of training that have so few effective reps per set that this might explain why some research or theorists suggest that the body needs an insane volume to generate growth. When the intensity of your sets is utterly piss-ass low, you probably do need 5X the volume as if you actually knew how to train with some degree of focus or intensity. But you’d be better off learning how to train with some degree of focus and intensity than just doing more bullshit sets. But regardless of how you get there, the key to turning on growth is doing a sufficient number of high-tension contractions. High-tension alone isn’t sufficient but without it, nothing happens. All of the insufficient tension work in the world simply doesn’t generate growth. But this raises a question which is this: Ho do we measure tension in the muscle? And the answer is that we can’t in the gym, not in any meaningful way. Not yet anyhow. But we have something we can use as a proxy for tension. Something that we can measure and track to give us some indication of what tension the muscle might be experiencing. If you’ve read much of my work, you know what it is. If not, you’ll find out next week. Where in addition to explaining what that proxy is (hint: it’s weight on the bar), I’ll move into a detailed discussion of the misunderstandings that come out of using that proxy. Of which there are many. Yeah, this is gonna be one of my stupid long article series for sure. But I need to get this written down once and for all. See you next week. Muscular Tension Part 2 By Lyle McDonald Ok, so in Muscular Tension Part 1 I looked at the topic of muscular tension in overview. What it is, what it represents and why it is important (i.e. as the primary initiator) in terms of muscle growth. This had to do with high-tension skeletal muscle contractions activating mechanosensors which turned on the protein synthesis pathway via mTOR . This requires two factors which are recruiting the fibers and then exposing them to some (currently uknown) number of contractions to activate the mTOR pathway via mechanosensors.. This can occur in a number of ways including lifting heavy weights (8085% of max or higher) which recruit all fibers from repetition 1 or by lifting lighter weights near or to failure. Both may end up achieving the same or a similar number of high tension repetitions. All roads lead to tension. It’s just a matter of how you get there. I ended up by addressing the idea of “effective reps” the number of reps of a set or workout that occur under full recruitment and activate mTOR. The idea being that only those effective reps really matter in terms of a growth stimulus, at least for the highest threshold muscle fibers. Effective reps can be achieved in a number of ways including multiple straight sets at an appropriate intensity with insufficient rest, rest pause and others. How you do it less important than that you do it acutely although I will still argue that there are better and worse ways to achieve that goal. I also posited that workouts where the sets generate very few effective reps might explain why some research and training theorists are positing enormous volumes of training. When every set is so ineffective/inefficient, you have to do a on more than if you did fewer sets that were challenging or accomplished something. And despite people’s hope that I was going to turn this into some deep molecular look at muscle growth, that actually wasn’t the purpose of my blathering. Part 1 was really just a longwinded background to explain why high muscular tension, regardless of how you get there, is the key to turning on growth. I ended by pointing out that, practically we lack a way to measure muscular tension in the gym. You can do it in the lab, eventually some type of patch/APP might exist. So we need some sort of proxy for muscular tension, something we can track in a practical sense to at least guesstimate the amount of muscular tension And I want to start today by looking at the proxy for tension that we have in a practical sense. More to the point, I want to look at not only some of the enormous misunderstandings that come out of the idea but places where using load without qualification is not a good proxy. Weight on the Bar as a Proxy for Tension While some number of effective reps under high tension overload is critical to the acute growth stimulus, we have the problem that we can’t measure tension in the gym yet. We need a proxy for muscular tension that we can measure beyond “I feel it/I got tired/I got a pump/I got sore, bro”. Something a touch more objective. And as I gave away in Part 1 and as anybody who has read anything I’ve written already knows, the real-world practical proxy for muscular tension is weight on the bar, the actual external load being lifted. Yes, there are other factors here. Lifting speed can impact this although it’s complicated, you get into peak and average forces and force/time curves and maybe I’ll write about that at some other time. Maybe some of the internal vs. external focus work. That sort of thing. But ultimately the load on the bar is the best quantifiable proxy we have. By this logic, lifting 120 lbs requires more muscular tension than 100 lbs. More external load means more muscular tension. Except when it doesn’t which is in a lot of situations. Before getting to that, you ask what I am basing this overall idea on. How is weight on the bar/external load a proxy for muscular tension? Remember that muscular contraction generates force. Also recall that force production is related, among other factors, to the physiological cross sectional area (XSA, effectively the size) of the muscle. Smaller muscles generate less force, larger muscle more force, at least assuming that the cross sectional area increases are made up of myofibrillar and not sarcoplasmic growth. This relationship is just staggeringly strong, like one of the strongest in any biological system, nearly a straight line relationship. At least this is true if you’re looking at somewhat artificial lab measures of force output under controlled conditions in the lab. Even outside the lab, the relationship is incredibly strong with lean mass correlating staggeringly well with 1 repetition max: more lean mass means a higher 1RM. It’s simply that once you get outside of the lab where you’ve attached an isolated muscle fiber to tension meters, it gets more complicated. You can’t go from a muscle is X size to this weight Y can be lifted. There are factors of biomechanics, fiber typing and neural factors that will all determine what actual external load can be lifted for a fixed amount of muscular force output. Two individuals may lift different weights if they are the same size and one person may lift more by changing technique (i.e. high-bar to low-bar squat). But this says nothing about the actual force output of the muscle. It simply points out that a given amount of muscular force/tension may move varying amounts of weight in the real world. So for 100 arbitrary units of force out of the biceps, a guy with shorter forearms will lift more weight than a guy with longer. It’s a physics and lever arm thing. And when people see that a seemingly smaller guy with better mechanics outlifts more than a bigger guy with worse mechanics, their simplistic conclusions is “Lyle is an idiot, muscular tension and load on bar have nothing to do with one another.” But this is not the argument, comparing two individuals to one another. It’s about the relationship for one individual between bar weight and muscular tension. Their limb lengths don’t generally change although technique can (again, high-bar vs. low bar squat). For the time being the statement being made is that the load on the bar will be related to the amount of tension generated/required by the one individual’s muscle mass for a given individual in a given exercise. So if you take Lyle the Crocodile, high-bar squatting 275X5 will require more force output and expose the muscle to higher tension than Lyle high-bar squatting 225X5. What Lyle might do in a low-bar squat doesn’t matter. What Bob the Builder does in either movement is irrelevant. I’ll address some of these issues later in the series in more detail. But this is far from the last time when external load on the bar and muscular tension may diverge: where the external load isn’t representative of actual muscular tension. I examined one of those in Part 1 and will do so again here. The Repetition Range Contradiction Astute readers may already see a contradiction with something I wrote in part 1 which was that you can reach high tension in a muscle via multiple paths: heavy weight for fewer reps, moderate weight for moderate reps or light weights for high reps with all three potentially leading to the same/similar numbers of effective reps per set. But the weights being lifted will be very different. Assuming a 100 lb 1 rep maximum, you might be using 85 lbs for 5 reps, 70 lbs for 15 reps and 30 lbs for 30 reps (i.e. 85%, 70% and 30% of max). Clearly 85 lbs is heavier than 70 lbs and both are heavier than 30 lbs. Aha “Lyle is an idiot, load and tension aren’t equivalent.” And I didn’t say that they were. But I never said that you had to expose the muscle to high LOADS but rather high TENSION and these are just different ways to reach high tension. And while my idiot status may remain in question, this is still missing the point. It simply requires further qualification. The mistake here is comparing different rep ranges in absolute terms. All three situations lead to full recruitment and absolute load and tension are not equivalent. Weight on the bar is still a proxy for tension, however. 100X5 requires more tension than 85X5, 85X15 requires more than 70X15 and 45X30 requires more than 30X30. Within a comparable situation, external load is a proxy for tension. Now I’ve already given a few of this series’ points away, qualifying some places where absolute load on the bar and muscular tension are not identical. Load is only a proxy for tension with certain qualifications in place. And I’ve only scratched the surface of some of those qualifications. There are places where a heavier load leads to less tension and a lighter load to more tension and I’m gonna look at a bunch of them in this series. Now, there is actually another, bigger issue to consider, one that might have fit into Part 1 but I didn’t have space. Because while acute tension overload sufficient to stimulate adaptation in the sense of a single workout is critically important, there is a factor that is more important over the long-term. Progressive Tension Overload While high muscular tension and a sufficient number of contractions/effective reps is the key to an acute training stimulus (i.e. within a workout) that’s not all there is to the topic because that’s just addressing an acute training stimulus. Most of us train more than once in our lives and what matters is how all of this works in the long-term. So let’s back up, we do it all right in the weight room, turn on the FAK/PA/mTOR thing, protein synthesis (which I’m told I don’t understand hahahaha) occurs, hopefully outstrips protein breakdown and the muscle gets bigger and stronger over time. What are the implications of this? One is that the tension overload that was sufficient to activate the mTOR cascade previously will eventually be insufficient to trigger that same pathway. So consider someone lifting 70% of max for 15 reps with 2 reps in reserve (and they do enough sets to stimulate growth). Say it’s 100 lbs right now. Over time the muscle gets bigger and stronger and that 100 lbs now only represents 60% of their maximum. Boom, we’re right back to ineffectual training where the number of effective reps is too low to be a good stimulus to further adaptation. The weight that was a stimulus a week or two weeks or two months ago is eventually no longer sufficient to stimulate growth. But you argue, what if they now take that new 60% weight to failure? Won’t it accomplish the same thing? Probably. But eventually 60% becomes 50% and on and on. I guess eventually that 100 lbs goes from being a heavy set of 8 to a set of 30 although realistically this would never actually happen for reasons I can’t be bothered to explain. And if you wanted to go that route it might work at least over the short term. Except that constant training to failure eventually burns people out and most people reading this don’t have a clue where failure really is to begin with which is the topic of another forthcoming article series. There is also the fact that nobody actually trains this way and most just pump out the same reps with the same weight. 225X8 stays at 225X8 forever and so does their muscular size. So I’ll work in this section from the assumption that you’re targeting a specific repetition/intensity range. And eventually the muscle adapts and what was a sufficient tension overload acutely isn’t. The weight that was an overload for a heavy set of 8 isn’t anymore (or is less effective as a set) because it’s dropped from 80% to 70% of maximum. Now what? Some would argue to do more sets That is, if you cut the number of effective reps per set in half as you adapt, why not just do twice the volume? That is, if 4 effective reps per set becomes 2 after you’ve adapted, just do twice the volume. When it drops to 1 effective rep per set, double it again so you’re doing 4 times as many sets as before. And when the stimulus per set is zero effective reps, you can do infinite sets and still not grow. Which would probably work but will also double your training times and just has you doing endless extra work (cutting into recovery) that just going heavier would accomplish more easily. Eventually you’ll get zero effective reps per set and MUST increase weight anyhow. Even the biggest “volume is the primary driver of growth” hardhead I know has written that “adding weight in the 6-12 rep range is THE key to long-term growth”. So rather than just tacking on sets to the limits of your tolerance, why not just add weight in the first place? Yes, fine, blah blah, when you’re very very strong adding weight can be problematic but I’m not saying do it every workout or week to begin with. Past the intermediate stage, it might be 4-6 weeks before a load increase is needed. Consider that elite PL’ers train for 4 months to add 5 lbs to their lifts. This isn’t a fast process beyond a certain point. Then again by the time this matters, when you’re lucky to gain 0.25-0.5 lbs a month of muscle and a few pounds per year to begin with, you’re pissing into the wind training anyhow. Adding volume won’t grow you any faster than adding weight either unless the added volume is what’s in your syringe. You might as well quit at this point because now you’re just fighting the slow slog to death and decay. But I digress. At the end of the day, no matter what else you do, to generate further growth, you need to increase the tension overload/requirements. Yes, there are other progression methods. But progressive tension overload in terms of increasing the load is the primary one over the long-term. This isn’t even debatable even if folks continue to debate it. And literally every study, no matter what they say they are studying, has progressive tension overload built into the protocol. The methods always describe that loads are being adjusted during the workout and throughout the study. It’s an assumed part of the protocol because without it nothing happens. And this means that what these studies are actually asking is “What happens if we compare these different frequencies or volumes WHEN PROGRESSIVE OVERLOAD IS ALREADY PRESENT.” Everything else being examined, EVERYTHING ELSE, is a secondary factor of study even if nobody but me seems to have noticed it. Now, the occasional study has worked on a base of not increasing load. The Haun et. al study I seem to be picking on lately (even if it was done methodologically very well) is one of them. So far as I can tell it didn’t add weight to the bar across the 6 weeks, it simply added sets to a fixed (piss-ass intensity) load. And the results, or rather non-results bear me out. The growth was sarcoplasmic rather than myofibrillar. Because all of the low-tension work in the world doesn’t stress the actual myofibrils because the number of effective reps (full recruitment under high tension) is so close to zero. it was also only 6 weeks long and over a longer time frame, what the fuck do you do? 32 sets/week, 48 sets/week, 64 sets/week? Yes, this is a bit of a strawman so spare me the bitching, I know nobody is suggesting that. But I think it’s a bullshit progression when you could have just started with a proper intensity set (i.e. not 10 reps with 4RIR), done 8 proper sets 2X/week and added weight to the bar instead. And I ASSURE you that a second group that had done that would have experienced actual myofibrillar growth without spending all day in the gym doing repeat warm-up sets every 8-10 minutes. Progressive overload is THE BASIS of all training and every sport requires it in some form or fashion. The stimulus that is sufficient today won’t be after some amount of adaptation and must be increased. And, in the context of muscle growth, given that high tension/effective reps is the stimulus to turn on protein synthesis, that means that tension overload has to increase over time. And the implication of that is: If we start from the standpoint of using weight on the bar as a proxy for tension, the implication is that increasing the weight on the bar is a proxy for progressive tension overload. Because if the 100X15 you were lifting a month ago is no longer a sufficient tension stimulus because you’ve adapted, that means that increasing to 110X15 (or whatever) will be required to create a sufficient new stimulus. And when that is no longer sufficient, you go to 120X15. If you never move up from 100X15, there is no further overload. Adaptation stops at the point it’s an insufficient tension overload and you get insufficient numbers of effective reps to turn on the FAK/PA/mTOR pathway. And ultimately, the idea of progression is far more important than what is being done acutely. Yes, the single workout stimulus is critical because without it adaptation won’t occur at all. But what happens over the long-term is more critical. It’s not the weight on the bar right now, it’s that weight is added to the bar over time. Importantly, you can only measure progression from the starting point of a given situation. Whether you go from 120 to 150X5 or 100 to 120X15 or 30 to 45X30 over some time frame, you’re applying progressive tension overload over time. The starting point doesn’t matter in an absolute sense outside of needing to be a sufficient stimulus for adaptation acutely. If 30X30 isn’t a stimulus in the first place, you won’t have to increase the load to keep growing because you won’t grow in the first place. You won’t even get “toned”. It’s that progression that applies progressively increasing tension loads so that the FAK/PA/mTOR pathway is activated and maintained such that growth continues over time. Back in the Real World People continue to argue against the above, especially in the era of “Volume is the primary driver on growth” bullshit. I am told that one brain surgeon argued that adding weight to the bar is a negative because it reduces his volume and I will laugh and laugh in 6 months when he has seen no progress and realizes I was right all along. I already mentioned that every study showing effective growth, outside of what it thinks it’s studying (frequency, volume, etc.) is done on a base of progressive weight overload. It is FUNDAMENTAL to the training process. Load is adjusted day to day and week to week because apparently “labcoats” understand the training process better than gym dipshits and Internet rocket scientists who think progressive tension overload isn’t the key part of stimulating growth. You can prove this all to yourself easily. Go to your gym and pick out a few regulars and note their current training poundages. Come back in a year. The guys who are lifting sufficiently heavier weights will have grown. And the guys lifting the same weights have not grown no matter how much volume or frequency they throw at it. They will be doing the same bullshit 2 hour chest workout every Monday with the same weights and look exactly the same as a year before. Ok, that’s not true. For some gym trainees, they will get bigger if they don’t add weight to the bar but focus on volume. But in this case it’s their volume of anabolic steroids. Trust me, double from 600 mg/week to 1200 mg/week and you’ll grow better than doubling your set count OR adding weight to the bar. Drugs beat out all of this. And I think if you look at a lot of arguments that volume is the primary driver on growth on growth, what you will find is that it’s not the training driving the bus but rather the special sports supplements being used. As I said in Part 1, a lot of goofy/stupid/inefficient/ineffective bullshit works pretty well when your dosage is high enough. And when you want to grow more, it’s easier to take more than to train more. Or consider how altogether too many women training: all the volume at worthless intensities and with no progression. And nothing happens for years. Then they cut volume, go heavier and work on progression. BOOM, they see more progress in 2 months than in the last 2 years. There are lessons to be learned here folks. Look at your own training: if you haven’t added weight to the bar for a year, you haven’t grown either. A ton of volume might have worked for a bit and that was it. Researchers know that adding weight to the bar is fundamental no matter what else is being done. How can anybody still be arguing against this in 2019? No matter what you want to argue or believe,when the rubber hits the road: No progressive tension overload over time means no long-term growth. In practice, that means adding weight to the bar. Or look at good NATURAL bodybuilders. In most (read: all) cases they are pretty damn strong. They aren’t powerlifter strong by and large (though some of the good naturals come from a powerlifting background). But that’s because they don’t usually practice very low reps and use different lifting techniques (another article for another day). Mind you, if you transition a bodybuilder to powerlifting, they tend to be extremely good at it. They’ve got the muscle mass (and hence strength potential) and once they get efficient with more efficient PL’ing techniques and get the necessary neurological adaptations, they move huge weights. But show me a big natural bodybuilder and you’ll show me someone who is pretty damn strong in the big picture, especially relative to smaller guys. You just don’t see good naturals farting around with light weights although you may see this among juiced bodybuilders who just let the drugs do the work. But some of the hugest pro bodybuilders (i.e. Dorian or Ronnie) who are immensely strong. Though remember I said you can’t really compare people like this. Comparing two natural bodybuilders, the guy squatting 405 isn’t automatically bigger than the guy squatting 315 because biomechanics and stuff all play a role. But the natural bodybuilder who went from squatting 225X8 to 315X8 will be bigger than he was. Far more importantly than their absolute strength is the fact that they have gotten stronger over the course of their career.The difference between being strong and getting strongER is another critical distinction people fuck up regularly and leads to one of the common misunderstandings of this topic. I’ll look at this in detail in Part 4. Hell, go back and look at all the big guys of the early 20th century, they mainly trained to get strong as hell because their main game was strongman performances. Specific bodybuilding training wouldn’t come until much later and the guys in the pre-steroid era just focused on getting strong as hell. And they got big as a consequence because in progressing from squatting 225X5 to 365X5 over several years, your legs can’t have not grown. Because nobody can add that much weight to the bar through simple technical and neural mechanisms. Snarkily, I find it interesting that one individual who will trot out these old timey guys to “disprove” the 25 FFMI cutoff is currently writing training programs meant to pander to current fads which have NOTHING to do with how those guys actually trained. They sure as hell didn’t train a muscle five times per week to “do more volume” and you shouldn’t either. They trained to get strong as fuck with relatively moderate volumes and frequencies and they grew as a consequence of that. There are lessons here folks. Now, don’t misread this. If you go from 250X5 to 260X5 and there may be no meaningful difference in muscle size. I’m not saying every pound you add to the bar equals some amount of growth because that would be stupid. I’m also not saying that there will be a linear 1:1 ratio of muscle gain to strength or vice versa (which seems to be a rather dumb assumption made by a fairly specific research group/individual) since there are clearly other factors involved. But beyond some point, as you build up the weight on the bar in a moderate repetition range, the muscle has to get bigger. As Dante Trudell put it so brilliantly “The key to growth is getting stronger in a moderate repetition range.” That sums up training for size. Note: I will maintain that irrespective of it’s other strengths (and there are many) Doggcrapp training “worked” for people because Dante got lifters to stop fucking about with the pump and volume and all of that irrelevant bullshit and got them trying to “Beat the training log and add weight to the bar over time.” That is, to get stronger in a moderate repetition range over time. And when they did that and ate, they grew. Because all of the fucking about without adding weight to the bar doesn’t work. QED. So as I mentioned in Part 1, let’s work from an early qualification that we are talking about moderate or higher repetition ranges. Three is at the low end and you have to do a lot of sets to get it done but 3-5 reps per set and higher up to about 30 reps per set near or to failure is where we’re talking about here. A Mid Article Summary So here are the key things to remember so far: 1. High mechanical tension for a sufficient number of “effective” contractions is the initiating factor in muscle growth via the FAK/PA/mTOR pathway 2. We can’t easily measure mechanical tension in the gym 3. Weight on the bar is, to a first approximation, a proxy for mechanical tension 4. Adding weight to the bar means an increase in mechanical tension which stimulates growth in the long term Where 3 and 4 are really the key focus of this series. And they are absolutely true except when they aren’t. Or rather they have to be qualified a bit. You can’t compare two individuals in terms of load on the bar, the absolute load may differ between rep ranges even if both can lead to the same high tension stimulus. They may be relatively more or less efficient at getting there but they all get there. In a sense it doesn’t matter because of #4. Progression is more important overall: where exactly you start is less relevant than where you end up. I mentioned others as well. One of which was the idea of comparing two different exercises and this leads me to one the common mis-understandings of the concept of “higher load means more tension” along with a favorite dumb-assed argument you see sometimes. To really address that, I need to bore you with some physics. Lever Arms, Torque and Force Production So remember back to high school physics, with free body diagrams where you had to keep track of different forces on a system and figure out what they were and stuff. I loved those things, like working a puzzle. I also love putting Ikea furniture together so take that for what it is. Anyhow, we can look at weight training through that concept although we only need to focus on two forces: the force generated by the muscles pulling on the bone and the force required due to the resistance being moved (air resistance doesn’t matter and we’ll ignore friction although it can matter on poorly maintained machines). Most things we do in the weight room rely on gravity for resistance but there are exceptions. Tubing pulls along the line of the tubing regardless of the direction and cable stacks allow the up and down gravitational pull on a weight stack to be changed to an angled or horizontal resistance. Many movements that don’t work with free weights such as the standing horizontal DB rotator cuff exercise works with tubing or a cable. There are also mechanically braked isokinetic machines, those old stupid pneumatic things, some electronic machines and water resistance is weird as hell because it pushes back in any direction the opposite of how you push against it. But that’s just detail mongering to shut down the nitpickers (I deliberately left out one current technology just so someone can bring it up and dismiss my entire article because they think I’m out of the loop. I’ll mention it in Part 4 for lolz). The key here is that, however you set up the external force of resistance, the force the muscle has to generate to complete the movement depends on the force that is opposing it. So if the force required to lift a weight is 100 arbitrary units, your muscles have to generate at least this much force to complete the repetition. And this is true regardless of how the resistance is created. I’ll just use gravity based movements to keep it simpler. Ok, so we have muscular force pulling against the force due to gravity and, in that sense, the heavier the weight being lifted the more force that is required to move it. Lifting 300 lbs requires more muscular force to move than 200 lbs. Well, kind of. Because there is an added complexity and this gets us into the concept of a lever arm. This is defined as the perpendicular distance from the axis of rotation to the line of force (in the case of weight training, this is the force due to gravity acting on a weight). This is shown in the image below which you can think of as representing a biceps curl. It actually shows two lever arms. The long one is the lever arm of the resistance from a weight held in the hand to the elbow and the down arrow is the resistance of gravity pulling on the weight (or whatever). The short one is the lever arm of the muscle, from the biceps to the elbow and the up arrow is the force pulling up. What you can see is that in different parts of the motion, both the lever arm of the resistance and biceps pull is changing length. Note how the resistance force is always straight down (gravity always and only points down) although the biceps line of pull changes slightly from straight up in the far left to the steepest angle in the middle. And simply, the longer the lever arm, the higher the effective force at the axis of rotation and vice versa: the shorter the lever arm the lower the effective force. When the forearm is perpendicular to the floor, the lever arm is at its longest and for any fixed weight, the force requirements will be the highest (this also defines the sticking point of the exercise). Early and late in the movement, that lever arm is shorter which is why it’s easier to start and finish a biceps curl than to get it through the middle. Note: There is a hugely critical practical training aspect that comes out of the fact that maximal tension only occurs at the point of the maximal lever arm but I don’t have space here to get into it (and it’s sort of tangential to the point of this series). Essentially the only time the muscle can experience maximal tension is at the sticking point. It must be lower at every other point in the movement, at least with free weights. Other types of resistance can work differently (i.e. cams try to alter resistance to match the force curve, chains overload the top). But it has some implications for exercise selection in terms of possibly selecting movement which stress a muscle maximally at different parts in the movement by changing where the maximum lever arm occurs. Another article for another day for sure. Anyhow, technically we are not concerned with forces, we are concerned with torque, a force that tends to cause rotation (like a torque wrench). Torque is defined as the force times the lever arm (the perpendicular distance between the force and the axis of rotation). For any given load or force, the longer the lever arm the larger the torque and vice versa. And this is a critical concept for the weight room. Torque in Weight Training Movements So in weight training, the axis of rotation is the joint that moves. And this is super easy to understand for isolation movements. In a biceps curl or triceps pushdown, rotation occurs primarily around the elbow. In a leg extension or the leg curl it’s the knee unless you are doing something very strangely. In a pec deck or DB flye it’s the shoulder (and the forearm if you use bad form). Pedants will point out that there is often small movement around other joints even in single joint movements. People will curl their wrist slightly on biceps curls or extend them on triceps in an attempt to shorten the lever arm and make the movement easier. The shoulder may move in a curl and the elbow or wrist may move on a pec deck or flye. All true but not relevant here as I’m focused on the axis of rotation for the relevant muscle. If the goal is training the pecs, the axis of rotation that matters is at the shoulder. Note: Real pedants will note that the axis of rotation moves around a little bit in the joint throughout the movement. This is true but the effect is miniscule, the practical effect irrelevant. It’s a bit of biomechanical nerd trivia that is interesting and nothing more. And knowing it won’t get you laid. This is a lot harder to picture for compound movements where there are multiple muscles acting at multiple joints all at once and you can technically define moment arms for all of them. So in a squat there is movement around the ankle, knee and hips with glutes, quads, hamstrings, adductors, calves and low back all playing a role. There are multiple lever arms and multiple muscular contributors, etc. I made the mistake of writing a term paper in college on squat biomechanics. Ugh. In a bench press there is movement around the shoulder (often in multiple planes depending on elbow position) and elbow with pecs, delts, triceps, lats, serratus anterior and others all contributing. For shitty benchers who bridge up off the bench there’s movement at the hip too. I fondly remember an article by Charles Staley about bench pressing for the hamstrings. Funny stuff. Ignoring that, in weight training movements, both the weight being lifted and the muscle are acting in the above fashion: at some lever arm relative to the axis of rotation. In most situations, the muscle is closer to the joint than the weight which means a shorter axis of rotation/lever arm for the muscle than for the resistance/weight being lifted. The biceps attaches closer to elbow than the weight in you hand. There’s a couple of weird exceptions, the calves are one (and I think one of the jaw muscles) and this gets into a bunch of stuff about 1st, 2nd and 3rd degree levers that I never remember because that’s what textbooks are for. These are just details. All of this goes to a point I made above which is the mistake in comparing two lifters. Even if they have similarly sized or strong muscles, they may lift drastically different external weights due to having different levers around a joint. A guy with a short forearm will curl more for the same muscular force output than a guy with a longer arm because the lever arm is shorter. The Real Implication of Lever Arms But there is a much more important implication of lever arms. The effect of the lever arm means that two entirely different loads (generating force due to gravity) can generate an identical torque at the axis of rotation. Remember that the resultant torque is the external force times the length of the lever arm. So say you’re lifting a weight that would require 100 arbitrary units of force to lift at a lever arm of x length so the torque is 100x. If you move that same weight to a point that is half as close to the axis of rotation the lever arm is now 1/2x and the torque is cut to 50x. The absolute load is the same, the torque at the joint is not. By the same token, if I double the force at the halfway point, the resultant torque at the axis of rotation will be identical to half the weight at the original position. I’ve shown this in the drawing below. AOR is the axis of rotation and I’ve shown a 100 unit force at distance x from the AOR and a 50 unit force at distance 2x from the AOR. In both cases, the resultant torque is 100x. In both cases, the muscle has to generate an identical amount of force to lift the weight. A smaller force applied at a longer lever arm can have the same or a higher resultant torque than a larger force at a shorter lever arm. It’s the whole you can lift the world with a long enough lever. It’s also why a longer handled wrench makes it easier to turn a frozen nut. For any given amount of muscular force, the longer handle means a longer lever arm and a higher effective torque at the nut. And in a muscular sense, that means that the absolute weight on the bar can’t indicate what tension it requires/exposes the target muscle to without considering the lever arm. And this leads into not only that bit of confusion but one of my truly favorite dumbshit Internet arguments. The Compound Exercise Mistake I could also call this the exercise comparison mistake but I like this title better since it’s usually an argument couched in the idea that, if load on the bar is a proxy for tension, and higher loads mean more tension, compound exercises MUST be better for growth because the weight on the bar is higher. I think the most common way I’ve ever seen this stated is like this: “What’s better for the shoulders, an overhead press with 300 lbs or a lateral raise with 30 lbs?” Which has so much wrong with it it hurts. It could be made for most other compound to isolation exercise comparison (i.e. what’s better, a 315 bench or a 30 lb DB flye). It actually works the opposite for squat and leg press since everybody can move more weight on the leg press than in the squat but I’m not getting into the vector math or physics of it because I’ll get it wrong. I’ll focus on the shoulder example since I see it most commonly and it’s just dumb as shit. First, how many legitimate 300 lb OHP’s have you ever seen? Unless you train with strongmen or elite powerlifters, I’m going to say roughly zero. Just like you haven’t seen many legitimate 400 squats, 300 benches of 500 lb deadlifts in the average gym. So it’s kind of a stupid example even if it’s only meant to illustrate a point. Second, those numbers are an idiot exclusion of the middle. Anybody who can OHP 300 lbs should be able to lateral raise more like 50-75+ lbs per hand (100-150 lbs total) depending on their mechanics and I’ll show you how I reached that conclusion below. Find someone with a huge OHP and have them do heavy laterals and you’ll see a similar relationship and it won’t be a huge OHP and a pitiful lateral raise. The example as it stands simply fails the reality check. Anybody who could OHP a ton can lateral raise slightly less than that ton but still a ton. Yes, I know, the people saying this are making a point between BADASS powerlifters and LAMEASS gym bros but it’s still a stupid example because the numerical comparison has no basis in reality. It’s an example containing the implicit conclusion that they want to make. And it’s dumb. Someone will counterargue that PL’ers lift all the weights and lots of gym bros never go above 30 lbs in the lateral. Which is true but making a different point which is about the bullshit nature of most gym bros training since they never add weight to their movements because the think things like the pump, or the squeeze or doing a shit ton of volume per se is more important than adding weight to the bar over time. Adding weight to the bar over time is the end metric for powerlifters and, frequently, they grow better than gym bro bodybuilders in my opinion (another article for another day). But again it’s tangential to the idea that a 300 lb OHP MUST be superior to a roughly equivalently heavy lateral raise. It’s only superior to a dumbass comparison example. Because what the example is really trying to say is that the higher absolute weight on the bar MUST be better for growth than the lighter weight used in the lateral raise. Because this is America and bigger numbers are better than smaller numbers. 300 is more than 30 (or 100 or 200) hence 300 is better. But in doing this it’s confusing absolute weight on the bar with actual muscular tension (remember I said that the key isn’t high LOADS on the muscle but high TENSION). The confusion is worse with the dumbshit weight comparison of 300 to 30 lbs since it’s a false dichotomy. But even if you make a much more reasonable comparison, say a 300 lb OHP to a 75 lb lateral raise (75 lbs in each hand or 150 total pounds), the assumption that 300 lbs requires a force output or subjects a muscle to inherently more muscular tension than 75 lbs/hand 150 total pounds has problems. Now I’ll assume here that the goal is to build the delts. Pedantic assholes will invariably comment “But OHP is better for delts and triceps” or “overall growth” or “all of those real world activities where you lift stuff overhead” or some bullshit but that’s not the point of my discussion or the stupid ass quote. The statement as made is talking about shoulder growth only and that is my singular focus. None of the rest of it matters. And the problem with the comparison is that it’s conflating the absolute LOAD on the bar with the TENSION experienced by the muscle. And there are two problems with this. Problem 1: The Lever Arm Issue Ok, so here’s a picture of me doing a DB OHP and a DB lateral raise at the longest lever arm that will be experienced. I did my best to line up the pictures top to bottom to make the comparison reasonable and fair. The red vertical line running through my shoulder is meant to indicate the axis of rotation. The red arrow dropped down from the weight is the force of gravity acting on the weight. And the green line is the lever arm, the perpendicular distance from that force and the axis of rotation. And what you can see is that the lever arm is roughly three times as long in the lateral raise as the OHP because I have long assed arms and a long forearm relative to my humerus. Note: I can see someone with a biomechanics background composing their critique of this right now. “It is clear that Lyle McDonald doesn’t understand this system since he is ignoring movement in other planes during the OHP and lateral raise and how that impacts on the resultant lever arm and torques. He’s an asshole and should be ignored.” Yeah, well, see here’s the thing. I am well aware of this but this isn’t an article about the physics of lifting and I’m trying to stick with concepts more than math. Assume that the humerus is in the same position in both movements (i.e. mid-scapular plane) so that is fixed in the system and the only consideration distance along the arm from shoulder to the weight. Anyhow, I have no idea if this is normal biomechanics or I’m just a weirdo. But let’s say the distance from shoulder to elbow is x and from shoulder to hand is 3x based on the extremely scientific method of eyeballing it. That is, the lever arm is three times as long for a weight held in the hand versus having it applied through the elbow. Ok, crap, I have to qualify something else which is that I’m trying to compare a movement done with two hands to the weights held in one. And this will end up getting confusing. Assuming the lifter is symmetrical, the weight being lifted with two arms is effectively split in half with each arm. OHP’ing 300 lbs means that each arm is having to put out 150 lbs of force. And that force will be applied at the elbow assuming it’s the forearm is perpendicular to the upper arm. What this means is that, with my roughly 3:1 lever arm length: 150 pounds at the elbow generates the identical torque at the shoulder as 50 lbs held in the hand: 150x. So if I have the muscular force to OHP 300 lbs, 150 lbs in each hand essentially, I should be able to lateral raise at least 50 lbs/hand. And the torque at the shoulder will be identical. And so will the muscular tension. If the lever arm of the OHP was closer to 1/2 that of the lateral raise (and for anybody able to OHP 300 lbs it probably is), that 300 lb OHP which is 150 lbs per hand should allow for a 75 lb per hand lateral raise, at least to a first approximation. Because both will create an identical torque of 150x at the shoulder. Ok, it’s probably not absolutely identical for some obtuse biomechanical reason that someone will dredge up but just consider this as a back of the envelope calculation and focus on the point: two completely different loads can generate an identical resultant torque at the axis of rotation. Lifting 150 lbs at 1/2 the lever arm is the identical torque to lifting 75 lbs at twice that lever arm. Yeah, comparing that 300 lb OHP/150 lbs in each hand to a 30 lb lateral won’t achieve that. The effective torque here would be 150x vs. 60x (or 150x vs. 90x for my long arms) and clearly the OHP is superior. But it’s a dumb comparison because anybody who can OHP that much will be able to lateral raise a lot more than 30 lbs. For an equivalently loaded lateral raise, the muscular tension requirements will be roughly identical despite the OHP having twice the external load. And once again we might rough estimate that the guy who can OHP 300 lbs, 150 in each hand might be able to do a lateral raise with about 75 lbs assuming double the lever arm. And while a physics teacher would have an absolute aneurysm over this, I’m going to write this in the next section as the 300 lb OHP with 150 lbs in each hand as having an effective force requirements of 75 lbs. Clearly this is dumb and wrong, 150 lbs can’t be 75 lbs but I’m tired of writing out arbitrary torque values. What I mean by this is that the 150lbs per arm that is being lifted is roughly equivalent to the 75 lbs per hand lateral at twice the lever arm. It’s just shorthand to save me some typing. But let’s start from a slightly different assumption, that the guy who can OHP 150 lbs/hand can only lateral raise 60 lbs in good form. Now the resultant torques becomes 150x vs. 120x and the OHP is still superior. Put in my weirdo wrong terminology, the effective 75 lbs of the OHP is still higher than than 60 lb requirement of the lateral. The case is made, compounds rool, noob. Or do they? Because there is more to consider. The Muscular Involvement Issue In addition to the lever arm issue, there is another to consider which is that the OHP uses multiple muscles to complete the movement: delts, triceps, pecs have a minor contribution, serratus and there are probably others. Which means that the total torque requirement for the OHP is not isolated to the delts: it’s spread out across multiple muscles. Now, how much is being contributed by each I couldn’t begin to rough estimate. It will depend on relative strengths of the muscles and such and I’m sure someone can find some obtuse EMG study on it to math it out. I don’t care. This is a concept discussion about the problems with the simplistic assumption that compounds are superior to isolation due to higher absolute loads on the bar. The point is that the total torque requirement of the OHP (and really any compound movement) is spread across multiple muscles. Again, I’m assuming that the 300 lb OHP is equal to 150 lbs per hand with an effective force requirement of 75 lbs due to the 1/2 as long lever arm. If the delts contributed 100% of the force requirements, that would be 75 lbs. Certainly they contribute a majority, that’s what prime mover means. But it’s not 100% no matter what. And we can contrast that to the lateral raise with 50 lbs in each hand where it is basically the delts contributing 100% of the force. Yes, traps play a role but that’s shoulder elevation, not humeral ABduction. I’m sure someone will point out a minor neck muscle. Whatever, there is no true isolation movement where only ONE muscle works. It’s just a matter of degrees: single joint movements are more isolated to a single muscle/group than a compound exercise which uses a bunch. For all effective purposes, the delts are the only muscle really contributing to the movement in the lateral raise. So they have to generate the entirety of force/torque requirements. If the lifter could do a 75 lb lateral raise, I’d state categorically that the lateral raise would expose the delts to more tension than the 150 lb/hand OHP with an effective 75 lb force requirement due to the lever arm and this is reduced further due to the delts not being the sole producer of force. Because the OHP would require less than 75 lbs of force output from the shoulder. But even at a 60 lb lateral raise, with the longer lever arm and only the one muscle effective working, the medial delts might still be exposed to more tension in the lateral raise than in the OHP. I’m not saying they absolutely are or are not and that probably depends on a host of factors such as the lifter’s mechanics and relative strength levels. Let’s wank about this mathematically. If the delts only contribute 90% of the OHP, the 75 lbs effective force becomes 67.5 lbs which is about 12% higher than the 60 lb lateral raise. At 80%, it drops to 60 lbs which is exactly the same as the lateral. And anything lower than 80% and the OHP will require less force than the lateral raise. I am not saying that any of these numbers are correct, this is a concept discussion, making a point about how the comparison as it’s stated is based on bad logic. But irrespective of the exact numbers, my point is this: the differences in muscular tension between equivalently loaded movement with severely different lever arms is not nearly the differential implied by the absolute numbers of 150 lbs and 60 lbs per hand (or 300 lbs and 120 lbs total). Because clearly the OHP isn’t requiring 2.5 times the force output (and hence exposing the muscle to 2.5 times the tension) in the delts as the lateral because 150 lbs is 2.5 times higher than 60 lbs. Depending on your assumptions about relative muscular contributions, it’s more like 5-10% different in either direction. The shorter lever arm cuts the resultant torque/effective force requirements which is then spread out across multiple muscles which further reduces the force requirement of the TARGET MUSCLE. Yes, I’m beating this dead horse because the assumption that compound movements are inherently superior for growth because you use more weight is utterly flawed. And that is what we are interested in here: the force requirements of the target muscle since that will determine how much tension/force they must generate and what tension load they are exposed to. Which is a very long way of making the point that while external load is a proxy for tension, you have to think about the situation a bit. You can’t just look at the load on the bar and draw conclusions about anything. In this case the qualification has to do with the mechanics of the movement itself. If one movement lets you lift twice as much due to having half the lever arm and more muscles contributing, it may require similar, slightly more or even a little less tension in the target muscle than another. It’s not inherently superior (outside of impressing Internet idiots) just because the number on the bar is higher. It might be. But it might not be. This actually brings up another issue that is often unconsidered. What Muscle is Experiencing Optimal Tension Overload? Recall that growth occurs when the muscle we’re targeting experiences high tension for enough contractions to activate the mTOR cascade. This means that far more important than performing an exercise in such a way as to generate effective reps per se, we want to expose the target muscle to the appropriate stimulus. If our goal is to train the delts for hypertrophy, the goal is to expose the delts per se to sufficient effective reps to trigger the FAK/PA/mTOR pathway. And this means that we have to consider what muscle is failing during a movement. So if you are performing a heavy set of OHP and your triceps fail early, you may or may not expose the delts per se to a sufficient tension overload or enough effective repetitions to turn on mTOR. That 150 lb/hand OHP with a 75 lb effective force requirement due to the lever arm might or might not be sufficient for the delts per se because there are other muscles which are involved. I’m not saying it will or it won’t and that will depend on a lot of factors such as mechanics and relative triceps strength. Someone with long arms or weak triceps will get less of an effective delt stimulus out of OHP than someone with short arms and strong triceps. And when you start to look at who responds to certain exercises what you see is this. People built to do certain movements get a lot out of them for the target muscle (i.e. bench for pecs). People not built to do them do not. And this is very likely to be a big part of why. But if your triceps are severely limiting and fail early, the delts might not get an optimal stimulus or less effective total repetitions. Certainly, the triceps got that stimulus but if you’re using the OHP to train the triceps, you’ve missed the point of this discussion. We’re talking about training the delts for hypertrophy. Not the triceps, not the OHP as a movement itself. We are concerned with training the delts for hypertrophy and nothing more. So consider a hypothetical situation where the weight you’re using for an OHP is such that the triceps are fully recruited from repetition 1 but the delts don’t reach full recruitment until repetition 6. On a set of 8, the triceps will get 8 effective reps but the delts will only get 2. Compare this to a lateral raise with the equivalent weight where full delt recruitment will occur in the delts from rep 1 and all 8 reps are effective reps. Even in the tension requirements are slightly lower in the lateral raise, if the triceps fail early, the effective stimulus from the lateral raise may still be superior. Again, I’m not saying that it absolutely will or won’t be. Rather I’m just making the point that the differential in tension isn’t nearly what the 150(75 effective weight) vs 60 lb values imply at face value when people simplistically look at the load on the bar. And even if the lateral raise still requires slightly less tension output from the deltoids, it may still allow for more total effective reps and a better stimulus for the delts since it’s not limited by the failure of accessory muscles. Note: People with some training experience have probably noticed that different types of exercises tend to “fail” in different ways. In compound movements, it’s most common for the movement to slow and get grindy and then fail at some part in the middle of the movement. So on a final rep of bench you might get it partway off the chest and then it stalls in the middle. Or you get it through the middle and still don’t make lockout. Same with OHP. In contrast, isolation movements often seem to just fail. It’s like one rep goes and the next won’t even start. It’s an on-off switch. And this is probably due to what I talked about above, the issue of multiple muscles contributing to the compound exercise versus only the one in the isolation movement. In the OHP, when your triceps start to fatigue but your delts are still relative fresher, your body can utilize different recruitment strategies to keep going and you can grind another rep. When your delts are cooked in a lateral raise, your delts are cooked and there is no movement to be had. Which I think indirectly points to part of what I was saying above: in many cases,the nature of muscular fatigue and what is fatiguing first in a compound movement often results in a poorer overall stimulus compared to the isolation equivalent where only the target muscle can fatigue and be trained. But I digress. Because lest we forget, this is still within the context that progression more than acute training stimulus is the more important issue. Regardless of which is superior acutely, progressing the OHP or equivalently loaded lateral over time should result in growth. This brings up a practical issue that I’ll get more into in Part 3 but should at least mention here. The Practical Issue of Progression In that progression more than acute loading per se is the critical factor in long term growth, we face the often difficult issue of progressing lateral raises compared to OHP (or any isolation movement compared to a compound movement). Where adding 5 lbs to the OHP may cause no problems but adding 5 lbs to the lateral turns it from strict to a technical shitshow where not even 1 good repetition can be done. This is an issue of percentages and load increments. In most gyms, 5 lbs (just under 2.5 kg) is the lowest increment most can increase a weight. And this represents a vastly different percentage increase depending on the base weight of the lift. On a 100 lb OHP, 5 lbs is only 5%. On a 30 lb lateral, it’s 16%. If you added 16% to the OHP, it’d get ugly too. Microplates can get around this but often a lateral raise is very hard to increase in weight while maintaining anything approximating technique. In which sense, the OHP might be arguably superior in a progression standpoint. At the same time, there is the technical nature of the OHP where you often have to dick around getting the bar around the face although again, this is practical issue not a tension one. This whole thing can be avoided by using a Hammer BTN press machine but everybody knows that machines are for noobs. And of course this pretty much applies to any compound to isolation exercise comparison. The lighter weights in the isolation movement make progression a practical issue. But that’s irrespective of the physiology. I’d note that women have this issue almost across the board in the weight room with only a few exceptions: the weight increments are invariably a much larger percentage of the weight being lifted compared to the same increment for men. Finding a way to microload exercises is often mandatory for female trainees in a way that it isn’t so much in men. The weight jumps available are simply too large. But these are both practical issues, not related to the specific discussion at hand in terms of bar weight and muscular tension not being synonymous. Knowing my nitpickers, I just like to cover all my bases. I’ll go into more detail on the above, in a different context in Part 3. Back to the Compound Exercise Mistake I won’t bother getting into it but all the above holds for many other movement comparisons. Bench press versus flye or pec deck for example. In the bench, the load is heavier but the elbow is bent and the effective load is 1/2 or 1/3 as close to the shoulder as in a flye or pec deck with the weight in the hand. That’s on top of bench using pecs, delts, triceps, a little lats while the pec deck uses the pecs. And triceps are likely to fail before pecs so someone with long-arms or weak triceps may get a wonderful tricep stimulus and an ineffective pec stimulus. Those people ALWAYS grow better pecs from more isolation movements because they are able to get a sufficient training stimulus for the pecs that way. It gets harder to examine for other movements without a lot of free body diagrams. I wanted to try to compare squat to leg extension but it’s way harder in the big picture to do so and I’m super lazy. Squat mechanics are much more complex, depth impacts on what muscles are being most challenged (most bench full range) and I can’t be bothered to try to show how it all works. How you squat, the depth and your levers all determine what muscles are most challenged and what tends to fail first. The same logic holds, just because someone can squat more doesn’t automatically mean that the tension on their quads is higher or that the growth stimulus is superior than in an equivalently heavy leg extension. Really the key factor to take away from this discussion is this: An absolute higher load on the bar may not mean a higher tension in the target muscle when comparing two different exercises. Lifting 300 lbs in one exercise does not inherently require or generate more tension on the target muscle than lifting 120 lbs in another if that 300 lbs has a much shorter lever arm and 6 (whatever) versus one muscle generating force. Quite in fact, the compound movement might expose the target muscle to less tension than with an equivalently loaded isolation movement. Even if it doesn’t, it might generate less effective reps per set for the target muscle due to early failing of accessory muscles. There are actually other implications of the above but I’m going to bump them to Part 3 for space reasons. Summing Up Part 2 Ok, so that got out of control to cover only a single issue but perhaps you’re seeing the point of all of this already. High tension overload is the key to turning on growth acutely. Over time we have to increase that tension overload to maintain the stimulus. Since we can’t measure tension directly, we need a proxy. And the easiest proxy we have is the weight on the bar. To a first approximation, the load on the bar will be an indicator of tension on the muscle. But only with some qualifications in place. You can’t compare two individuals to one another as their mechanics will change how much weight is lifted for a given amount of muscular force. You can’t compare different repetitions in absolute terms either. And you can’t compare different exercises where, due to changing mechanics, lever arms and muscular contributions, the absolute load being lifted will not indicate per se how much tension a given muscle experiences. A 300 lb bench is not inherently more tension than a 100 lb pec deck/flye (yes, pulleys, yadda, you know what I mean) since the lever arm at the pec is 1/2 to 1/3rd as short and you’ve got multiple muscles contributing versus one. It might or might not be but the idea that 300 is inherently more tension than 100 because the number is three times as large is based on simple logic. And simple logic is almost always wrong. On the compound movement, smaller muscles will usually fail before larger so while the triceps or anterior delt might get a sufficient stimulus from the set, the pecs might not depending on the relationships between muscles. Guys built to bench which usually means thick chest and short arms can get a great pec stimulus from bench because their pec and triceps strength is closer. Guys with long arms or just weak relative triceps don’t get much out of the flat bench. And the same holds for most movements. Guys built to squat think they are GREAT for legs and for them that might be the case. And people not built to squat can toil for years at the movement and get jack shit out of it for growth of their legs. Their low back on the other hand. And neither can usually understand the other. And much of this is sort of irrelevant in a long-term sense. Progressive tension overload is more important than the acute stimulus. In the sense that weight on the bar is a proxy for tension, adding weight to the bar is therefore the proxy for increasing tension requirements. As I’ll discuss next, there are other places where heavier weights may mean less tension, lighter weights may mean more tension, etc. And this is true even within the context of the same individual performing the same exercise in the same repetition range and applying progression. Tune in next time, true believers! Muscular Tension Part 3 By Lyle McDonald So I’ve already covered a lot of information in Part 1 and Part 2 of this series on muscular tension and believe it or not I’ll wrap up here. Let me try to rapidly summarize the previous 2 parts (rapidly meaning like 6 paragraphs). High mechanical tension for some number of “effective” contractions is the primary initiating factor in muscle growth; this occurs via the FAK/PA/mTOR pathway. Activating this pathway requires that muscle fibers are first recruited and then exposed to enough high tension contractions (the amount needed per set, per workout or per week are currently unknown). You can get to a number of high tension “effective” contractions in numerous ways: heavy weights (80-85% or heavier) for lower repetitions or moderate/lighter weights for moderate/high repetitions so long as the sets are near or to failure. We can’t measure mechanical tension easily in the gym (yet) and need some objective marker we can use. Weight on the bar is, to a first approximation, a proxy for mechanical tension and heavier weights should lead to higher muscular tensions. But only with the understanding that you can’t compared dissimilar situations. You can’t compare two different individuals, you can’t compare different repetitions ranges and you can’t compare different exercises (i.e. compound vs. isolation) in terms of the absolute load on the bar and conclude anything meaningful. You can only compare like situations to like situations. For the compound versus isolation issue, differences in the lever arm and number of contributing muscles can make it such that an equivalently loaded isolation movement may generate similar, the same or more tension despite a lower external load. At the very least, the differences in tension are nowhere close to the magnitude implied by the weight differential. That you use double or triple the weight in a compound movement doesn’t mean the tension on the target muscle is double or triple. As importantly, due to the potential for non-target muscles to limit poundage and fatigue early in the compound movement, the isolation exercise may generate more effective reps even at a slightly lower tension stimulus. 8 effective reps at 90 arbitrary units of tension will be better than 2 effective reps at 100 arbitrary units in terms of stimulating growth. Over time, with a sufficient acute stimulus, growth occurs and the previously sufficient stimulus is now insufficient. Progressive tension overload must occur over time. Given this, the starting point in absolute terms is less important than the progression over time. 30X30 reps may be less than 85X5 in absolute terms acutely but this is irrelevant so long as both are a stimulus. If a trainee goes to 45X30 or 100X5 from the starting point, they have applied progressive tension overload. Just as weight on the bar is a proxy for tension per se, adding weight to the bar is, to a first approximation, a proxy for progressive tension overload. Except when it isn’t. And while the above really leads into the main part of Part 3, I need to address two other issues first. A Clarification on Progressive Overload Something I thought I had made somewhat clear in Part 2 seems to have been missed. Or I just didn’t repeat it 6 times or something so it didn’t take. This had to do with the frequency with which progressive overload (of any kind) has to be applied. A mistake some make is in thinking that progression must occur every workout or every week. That you have to overload the body more and more in this linear fashion to get adaptation. And that just isn’t the case. Other sports certainly don’t do this or event attempt to. An endurance athlete might be waiting 4-6 weeks or more to get any adaptation that allows or necessitates a change in training volume or intensity. The same is true for other athletes. As adaptation rates slow down, the same training load remains a sufficient training load for longer and longer durations. Even when you see those 3 week ramp/1 week deloads in old school periodization, just remember that it was as much to match with drug and school schedules as anything else. They’d start submaximally, ramp, ramp, overload and take a deload week while they dropped the drugs or the kids went back home to their families. Rinse and repeat. Certainly beginners can usually add weight at almost every workout but this is due mostly to learning to lift, neural adaptations, etc. rather than changes in muscle mass which take much longer. Of course can and should are different things and once the weight is sufficient to let them ‘feel’ what they are doing in the exercise, slowing down the weight progression may allow technique to get more stable and/or not degrade when you they add weight too rapidly. This phase will usually continue for at least the 6 month mark and sometimes longer although the frequency with which weight can be added will slow over time. Even into the early intermediate level of training (years 1-2/3 of proper training), it’s usually possible to add weight pretty consistently, at least week to week, over relatively short periods or training if someone is eating sufficiently. My own Generic Bulking Routine (GBR) for example. It starts with two submaximal weeks at perhaps 80-85% and then 90-95% of previous best to get a little momentum (and give a deload from the last cycle) before at least attempting to add weight to the bar consistently over the 6 weeks of the cycle. Maybe you don’t do it every workout but you should do it as often as possible and most can do it at least weekly for that time frame. Doggcrapp training cycles are very similar although Dante’s system is much more about muscular failure than mine. That’s a difference in volumes for the approaches, his are lower per workout than in my GBR. You cruise for 2 weeks and then blast for 6 trying to beat the record book as often as possible while eating enough. Remember that there is a 3 exercise rotation in many cases so you’re only trying to beat the same exercise number every 3 workouts. As you get stronger in a moderate repetition range over time and eat, growth ensues. My specialization cycles are drawn up similarly but there you’re focusing on two muscle groups and hitting it HARD for 4-6 weeks tops. When you’ve only got two muscles to target so all of your “adaptational energy” (whatever that means) goes into them and you can push it pretty hard. Even there you might only go up every other workout in practice. The goal is still to add weight as best as you can but that’s still within the limits of adaptation rates, practical weight increments and what I’ll discuss later in this part of the series. At the advanced intermediate level of training (years 2/3-4 years of training), you’re simply not adding weight to the bar that frequently. Nor do you need to. Ok, fine powerlifters often do this but it’s always from a submaximal starting point. Coan’s old routines followed this nice linear progression for the most part but he was starting well below his goal weight at the meet. So he’d start at 75% of his max and build up over 12-16 weeks to hit a new PR. But assuming loading is relatively near to limits to begin with (no further than 2-3 reps from failure), adding weight more than every 4-6 weeks tends to be unrealistic at this level. Note: Some powerlifting systems do attempt this but it’s usually a 3 week cycle where they have (re)introduced a new movement and attempt to set records in it over those 3 weeks. But this is generally maximum singles to begin with and those adaptations can still be neural in the short term. It’s also on a base of the previous weeks and months of training that have hopefully brought up muscles involved in that movement so there is more maximum strength potential. But 3 weeks is not 3 months. An advanced lifter will not add weight to the bar in any consistent fashion over a 3 month training cycle. Note 2: Tricksters will use approaches like this to deceive clients. They recommend changing exercises every 3 weeks so you can “progress every week”. What they leave out is that it’s mostly neural (re)adaptations when you switch movement. It takes you a week to remember the movement and then you make fast perceived progress. You improve by 5% every 3 weeks but it’s the same 5% over and over again rather than actual long-term progress. This is simply a function of how rapidly someone is gaining muscle or strength at this stage which is not very rapidly at all. You’re not adapting so quickly that your current sufficient training load becomes insufficient in any short period of time not unless you’re still getting some rapid neural adaptation. Those 10-20 sets/week or whatever at a sufficient intensity will be a stimulating load for a pretty long time and you won’t have to change anything. You don’t have to add weight to the bar and you don’t have to add volume very week unless you started with an insufficient training intensity or volume to begin with. So don’t do that. This was even one of Mike Isratael’s “arguments” in the Debate that Settled Nothing. He argued that adding volume every week was safer/better than adding weight every week. Perhaps. But who said that an advanced lifter should add weight to the bar every week in the first place? I certainly never have so it was an argument against nothing to begin with. Even if it’s safer to add volume weekly, it’s still totally unnecessary. At that level you don’t have to ADD anything week to week in the first place to get a stimulus so long as it’s sufficient to begin with. In fact, you probably shouldn’t. At this point just set up the right combination of volume and intensity parameters and wait it out for the adaptation to occur and then make a progression. In this situation, I usually recommend that every fourth week or so the lifter do a test on your last set of an exercise and go to failure on it (this assumes it can be done safely and they know where failure actually lives). If you’ve been working for heavy sets of 8 and get 12 on that final set, go up in weight at the next workout. If not, stay the course until you can. If you’re trained and can accurately use them, you can use RPE, Reps in Reserve or Reps to Failure as a gauge. If your goal is to work at a 1-3 RIR/RTF, and you’re working at a 4+, add a little weight because your training has become too light to be worth a damn. Note: This brings up a separate issue, whether or not we should adjust loads on a given set or for a series. So say you’re doing 4 sets of 8. The first set is a 3RIR and this falls over the series of sets to 2,1 and finally zero. Some argue that the first set isn’t optimal and you should adjust it upwards from the get go. Then you can decrease the weight (called by some reverse pyramid training or RPT) as needed to maintain the rep count. Basically that you should treat the sets individually. When the first set is too easy, adjust it regardless of the latter sets and so on. If at the next workout the first set is at the appropriate place and the second set is too easy, adjust the second set at the next workout too. Basically when a given set in a series is not heavy enough, you adjust that outside of any adjustements to the other sets. This tends to keep lifters a lot closer to failure but certainly can work if volume is relatively low to begin with. With higher volumes I think it will tend to lead to burnout. Trying to do 8 sets to true limits in a workout by microadjusting each one of them is just too grueling. To address this in full is probably another long-winded article series but that’s why I’m writing this tension thing, as background for those subsequent series. So rather than worrying about day to day or week to week progression or any of that at this level of training, just set up a proper workout in terms of volume, frequency and intensity and wait for the adaptation to occur. You don’t have to add or change anything at this point over fairly extended periods. A proper overloading workout will stay a proper overloading workout until it’s not and that takes a while. It might be a few weeks it might be longer. Change when you need to change and it’s all good. And at the very advanced level (4-5 years+ of proper training)? Well, I already addressed this. When you’re gaining 2-3 lbs of muscle per year (if that), you’re pissing into the wind with your training no matter what you do in the gym. The rate of muscle gain won’t make your current training poundages stop being a training load for freaking ever. When elite PL’ers and Ol’ers take 12-16 weeks to make a 2.5 kg/5 lb improvement on their max there’s simply no rush on progression. Adding weight or volume weekly or bi-weekly or monthly won’t do anything to hasten the process unless it’s your volume of anabolics because you can’t force growth. At this point it’s more about maintenance as age starts dragging you back into the mire of suck. Time for HRT/TRT/higher doses because that’s all that works here. And with that out of the way, back to the point which is about the exceptions to the idea that load on the bar per se automatically indicates tension or that adding weight to the bar automatically means an increase in tension. A Brief Digression on Exercise Selection Before getting to that I want to reiterate and expand on a point I made in Part 2 regarding comparing different exercises because it subtly changes/qualifies, one of the points/statements I made in Part 2 I gave as a hypothetical a situation where someone with long arms and weak triceps might have a situation where the triceps reach full recruitment and fail much earlier than the delts in an overhead press. So for a heavy set of 8, the triceps might see 8 effective reps and the delts only 2 or 3 or whatever. In contrast, the equivalently loaded set 8 in the lateral is, by definition, exposing the delts (essentially working alone) to the high tension stimulus. So 8 effective reps occur in the medial delts providing a superior growth stimulus. And this isn’t really a hypothetical except for my specific numbers being made up to make an example. Clearly in any compound movement, failure will almost always occur in an accessory muscle before the target muscle. How much earlier depends on a lot of factors. But by definition the heavy set of 8 or 12 is limited by what the accessory muscle can do for 8 or 12 reps. And this will impact how many effective reps the target muscle experiences. Which changes the original statement about effective reps per set to the following. Fundamentally we are not really concerned with the number of effective reps per set for a given exercise per set. We are concerned with the number of effective reps per set for the target muscle. Let me reiterate that I am talking only about hypertrophy here. Not function or increasing a given exercise. To improve the OHP you have to OHP. To improve the squat you must squat. But if the goal is increasing medial delt size or leg size, what matters most is the effective tension reps for the deltoids or quads or hamstrings and nothing else. If your low back limits your squat, it may get a fine growth stimulus. But your legs may not due to that limiting factor. This gets into exercise selection which will probably be a follow-up article series. For now I’ll simply say that exercise selection for hypertrophy must only meet the criteria of allowing a given individual to safely perform and progress an exercise that puts sufficient tension overload on the target muscle. And there will be no absolutes in this regard. There are no best exercises for hypertrophy. There are only best exercises for a given individual. Back to Progressive Tension Overload So back to the topic, the idea that adding weight to the bar is an objective proxy for progressive tension overload. Except when it isn’t. Because even given all of the above qualifications, there are still places where the assumptions that 1) the weight on the bar indicates the tension on the muscle 2) an increase in weight on the bar means an increase in tension are incorrect. That is, in certain situations, even for the same person performing the same exercise in the same repetition range, lowering the weight may increase tension on the target muscle and raising the weight may decrease it. To be honest, both examples are just two sides of the same coin but I’m wordy enough to make them separate topics and I find that if I don’t beat the dead horse with examples, people miss my point and then misrepresent what I actually said like they did with the progressive overload thing. When Lower Weight Means More Tension First let me look at the situation where lowering the external weight on the bar may or will result in increased muscular tension in the target muscle, an idea that seems to contradict everything I’ve written so far. If the weight on the bar is a proxy for muscular tension, how can lowering the weight on the bar increase muscular tension? The issue here has to do with technique and the fact that it is entirely possible to do a heavy set of seemingly effective reps per exercise (i.e. a heavy set of 8 or 15 or 30 to failure) with either a minimal or nearly no involvement of the target muscle. You can probably already see where this is going. And you can sure as hell see this in every gym every day. So we have our typical macho male trainee who is doing biceps curls. They are going too heavy because of course they are, throwing (not accelerating) the weight out of the bottom, leaning back and cheating the weight up through whatever means necessary. They probably talk about the great low back pump (or cramp) they get from their arm day a lot but rarely about biceps fatigue. “Bro, I’m just not feeling my arms for some reason.” “Bro, you just need more sets.” Hell I’d half argue that the excessive volumes that seem to be “needed” by many is just a consequence of their exercise choice or form not targeting the muscle effectively (on top of their intensity being piss-ass). If the way you do an exercise technically only gets 2 effective reps per set when you could have gotten 8, you seem to “need” 4X the volume to get the stimulus. Except that what you “need” is to learn to lift correctly and with intensity. Now you have them strip the weight down by half or whatever and lift properly with strict technique. Nice upright torso, elbows locked by the body, squeeze or accelerate out of the bottom with continuous contraction to the top, nice squeeze at the top (peak contraction, baby), a controlled lowering, maybe even a brief pause at the bottom to dissipate the stretch shorten reflex before the next repetition. Repeat. Sometimes locking someone into a machine can make it better since it tends to limit technique shenanigans. This isn’t a guarantee, people still do goofy shit on machines when they go too heavy which is basically always for male trainees. Suddenly they report that their biceps feel something, they get a pump during the workout (for what little that means) or get sore the next day (for the even less that that means outside of indicating that they actually trained their biceps for the first time in forever). Despite cutting the external load, often significantly, the tension in the target muscle is now much higher. Those 8 crap reps that hardly exposed the biceps to any tension at all are turned into 8 quality reps that do. And 8 effective reps for the target muscle always beats out a smaller number of less effective reps even if the load on the bar is lower. Back training is an unbelievably common example of this. Go into any gym any day of the week and watch people train back, rows or pulldowns and it’s just a nightmare to watch. They go way too heavy, heaving their upper body back and forth to get the weight to move, their shoulders never moving from a protracted position and basically arm pulling the entire time. They finish leaned back with shoulders forward and chest dropped and the handle maybe half way to their torso. They never feel it in their back but talk about how pumped their arms get. I suppose that makes up for their lack of a training stimulus on arm day. Now you cut the weight and have them actually use proper form. You get them to use an upright torso with minimal forwards and backwards lean. Squeeze/accelerate out of the bottom, keep the chest high and emphasize this in the peak contracted position, get a good squeeze between the shoulder blades (as their training partner or coach/trainer, put your finger tips on the inner border of the scapula and cue the squeeze by bringing your fingers together in back. Always ask first before you touch anybody in the gym), a controlled lowering to extension. Cue them to think about using their hands as hooks and think about driving the elbows back instead of pulling with the arms. Boom, suddenly they feel it in their back. Despite the lighter external load, the target muscle is now being exposed to far more tension. Now, in this situation, it’s likely that the biceps are being exposed to less tension due to the reduction in weight. But presuming that their goal of training back is to train the back, this is kind of irrelevant. And so long as you fix this person’s shitty technique on arm day, that’s taken care of. Now they can train back on back day, arms on arm day, and use an actual low back movement to train their low back rather than poorly done curls and rows. And everything will be right in the world so long as you can now convince them to add weight to the bar over time. That last one seems to be a lot harder these days for some reason. Even on an exercise like chest, a lot of guys heave around a lot of weight without feeling much in their pecs and there are all manners of goofy things lifters do on flat bench. When you cut the bar weight and teach them to bench with the pecs, they start actually using their pecs in the movement. Pump, soreness, yadda, yadda. More importantly, growth over time. Perhaps for the first time. The external load may be lower, and the tension in the delts or triceps may be reduced to be sure. But the effective tension on the pecs is increased and they actually get a training stimulus and grow. When it leads to technique improving or actually being correct for the first time, a reduction in external weight may lead to MORE tension on the target muscle. Squats are Complicated The same holds for other movements where excessively heavy weights cause problems and this is often a range of motion as much as technique thing. Think about the guy partial squatting the world. Or partial leg pressing the world. It looks really impressive but they don’t seem to get much out of it for their legs. Yeah, it feels heavy (some call it soul crushing) but their legs never really improve. Now, cut the weight in half and have them actually do a full range of motion: below parallel for the squat or to whatever depth to avoid back rounding on the leg press. Suddenly their legs get TORCHED despite the load being much lower in absolute terms. There are a bunch of reasons for this and you’re not only getting different muscular involvement but huge changes in the lever arms and hence effective torques around the joints which means huge changes in actual muscular force requirements and hence tension (there’s also a bunch of detail mongering with length-tension relationships over a fuller range of motion and this is NOT the place for that discussion). And I’m not going to try to describe it verbally or draw pictures of it. I honestly wish I’d stop bringing squats up because it’s so complex to describe or visualize. Just focus on the concepts. The lever arms at the top of a squat or leg press are very short so there is a huge mechanical advantage in that range. This is why people can partial squat enormous poundages or leg press with every plate in the gym and 2 dudes standing on top and still not work very hard. An old training partner of mine was a beast squatter, doing 405X5 and 315X20 rock bottom high bar. I saw him do something like 800 in a top end partial squat. The 405X5 was still a much greater effort for him than doing double the weight for a couple of inches. Once we tried isometrics in the power rack, which was bolted down to a piece of wood. In the top range he nearly pulled the rack out of the wood. That’s how strong the mechanical advantage is in the range. It’s great for ego. Less so for training the legs. It’s why guys who compete in PL feds that allow high squats can lift much more than guys who squat in feds that don’t pass what we used to call bullshit but which is now considered legal. There are a few factors here actually. Suits and briefs and gear are part of it, the shorter lever arms at the top are part of it and avoiding the sticking point as you come up from below parallel is a huge part of it since that tends to be what limits the overall movement: what you can get through the sticking point. This was the mistake in the Power Factor Training concept: they confused mechanical work (load lifted through distance) and power (load lifted through distance over time) with muscular/metabolic work (complicated as hell) and assumed that the first two automatically led to the third. That is, their assumption was that working in the strong range of motion, where mechanical work and power (sort of) is maximized would lead to metabolic work being maximized. PFT wasn’t just wrong but it was exactly the opposite of right: a greater range of motion with a lower external load will generally require less mechanical work (depending on if the reduction in weight on bar is or isn’t offset by the increase in distance moved) but far more metabolic/muscular work (which is what matters in terms of growth). But this is what happens when you let a pure engineer try to apply things to human physiology. At least get a bioengineer in there. This is a little bit more complex in the above example due to how muscular involvement changes throughout certain movements. In the squat, certain muscles are used to relatively more or less degree at different ranges of motion due to the joint actions that are occurring and where the maximal lever arms and changes in length/tension are occurring. So glutes tend to come in most when you deep squat, quads out of the hole, hamstrings near the top. All that stuff. Technique (i.e. high bar vs. low bar) also plays a role since you’re changing the amount of flexion around the knee and hip along with a bunch of other stuff and this changes torques and lever arms and….. Sit back more and depth is typically higher and you get less knee flexion and more hip flexion and vice versa. God why do I keep trying to describe squats? A partial squat may very well be putting a lot of tension on certain muscles but not others. Bodybuilders long did high-bar narrow stance half range squats to focus on the quads without involving the glutes. They deliberately limited the range of motion to focus on the part where the quads were providing the force. It also let them overload that range since they weren’t limited by what they could get through the sticking point. They not only took certain muscles (so those muscles got less or no effective reps) out of the movement but weren’t limited by the sticking point of a full squat. In contrast, a full squat may put a lot of tension on a different set of muscles but not the first set because different muscles are working maximally as you get from below parallel out of the hole with mechanics improving as you get closer to the top. In the full squat, you’re also limited by the weight you can get through the sticking point so the bottom portion may experience the heaviest load/tension and the top portion much less. It’s why getting out of the hole is the hard bit and locking out usually isn’t (yes, I know people stall near the top for various reasons). And why PL’ers use things like chains and bands to overload the top which is a whole separate thing. I should stop using squats as an example, it’s way too confusing and now I have a headache. So for the squat example you have to get further up your ass, so to speak, in terms of which muscles you’re focused on (there aren’t squat muscles) during the movement and what style of squat or range of motion you work through. Is your goal to train the squat, focus on the quads, the glutes, all of them or what. Mental note: stop talking about this before my head explodes. Ignoring squats per se, this is an issue inherent to compound movements, however. With multiple muscles contributing and often contributing maximally at different parts of the movement with changing lever arms and potentially different maximal lever arms for each muscle at different portinos of the movement, you have to start worrying about what muscle may be experiencing maximum tension requirements where in the movement. A bottom range bench is different than a top range bench in terms of what is most involved muscularly. People just seem to cut range of motion on squats more than on benches on average (this is discussed more below which is why I’m skirting it for now). Ok, No More Squat Discussion A final weird example: calf raises. We’ve all seen the guys with no calves who can move the entire stack on calf raises and if you watch closely, they all do the same thing: they bounce out of the bottom.