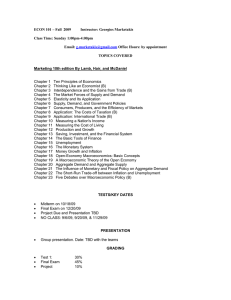

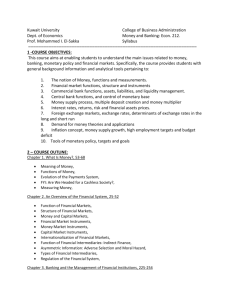

Economics of Money, Banking, and Financial Markets Textbook

advertisement