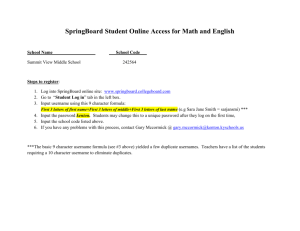

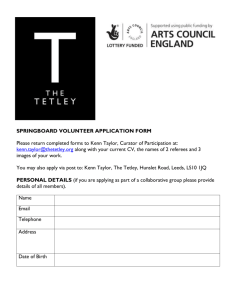

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320339877 A general theory of springboard MNEs Article in Journal of International Business Studies · February 2018 DOI: 10.1057/s41267-017-0114-8 CITATIONS READS 410 14,897 2 authors: Yadong Luo Rosalie L. Tung University of Miami Simon Fraser University 186 PUBLICATIONS 30,628 CITATIONS 83 PUBLICATIONS 8,757 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Yadong Luo on 21 February 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. SEE PROFILE Journal of International Business Studies (2018) 49, 129–152 ª 2017 Academy of International Business All rights reserved 0047-2506/18 www.jibs.net PERSPECTIVE A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo1 and Rosalie L Tung2 1 School of Business Administration, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL 33124-9145, USA; 2 Beedie School of Business, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada Correspondence: Y Luo, School of Business Administration, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL 33124-9145, USA e-mail: yadong@miami.edu Abstract The springboard view has become one theoretic lens to analyze emerging market multinationals (EMNEs) in the past decade. A decade after its first introduction in 2007, new developments offer keen insights on these firms and MNEs in general that aggressively engage in critical asset-seeking. We compare this view with other IB theories, highlighting their differences as well as complementarity. We articulate unique strengths and weaknesses of EMNEs, including their vulnerability and complexity caused in part by home country institutions. We discuss amalgamation, ambidexterity, and adaptation advantages that differentiate springboard MNEs from more established advanced country MNEs, and explain why and how springboard acts should be analyzed along with global competitiveness augmentation. We introduce an upward spiral concept to advance our understanding of linkages between springboard and post-springboard activities, and explain some critical crosscultural and human resource management issues in the process. To help continued research on springboard MNEs, we highlight macro- and micromanagement issues that are particularly worth exploring. Journal of International Business Studies (2018) 49, 129–152. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-017-0114-8 Keywords: springboard perspective; EMNEs; strategic behavior; emerging markets Received: 30 August 2017 Accepted: 1 September 2017 Online publication date: 11 October 2017 INTRODUCTION We revisit the springboard perspective for fourfold reasons: First, as emerging market MNEs, a focus of our original springboard perspective (Luo & Tung, 2007), continue to grow in numbers, size, and importance in the global economy, they face many new challenges. Our understanding of their unique ownership- or firmspecific advantages and disadvantages as well as their peculiar strategic behavior remains inadequate. Second, there are many new insights, questions, and issues that have arisen after the springboard view was introduced a decade ago. We are grateful that the view has been impactful but humbled too that additional insights and advancement are needed to reflect the changes in the global economy to capture more adequately the complexity, heterogeneity, and vulnerability of these firms. Third, it has been intellectually phenomenal to see the swift and substantial growth of research on such MNEs, including quantitative and qualitative studies over the past decade. Still, we feel that there is ample room in the field to enrich theorization of what is unique about these MNEs and how the springboard perspective is different from yet complementary with other IB theories. Fourth, the perspective can be applied to A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 130 MNEs in general to the extent that these firms aggressively seek strategic assets from the outset of outward FDI (OFDI) to augment their home capabilities and use their strengthened capabilities and improved home base to better compete globally. We thus use two terms of MNEs in this article – EMNEs referring specifically to emerging market MNEs, and springboard MNEs (SMNEs, hereafter) referring broadly to MNEs that expand through springboarding. EMNEs, still a central focus of this article, are the premier subset of SMNEs. The growth of MNEs, springboard firms included, is significantly affected by geopolitical and economic conditions at home and abroad. Factors such as the weakening demand and declining commodity prices, accompanied by depreciating home country currencies, have recently affected the internationalization of MNEs (UNCTAD, 2016). Still, EMNEs have fundamentally changed OFDI and MNE landscapes, and are in the process of reshaping the world economy. Over 120 emerging economies have engaged in OFDI, and there are now more than 30,000 MNEs headquartered in these economies (Chaisse, 2017). OFDI by emerging market firms rose from approximately US$1 billion during 1980–1985 to US$409 billion in 2015. Six of the top twenty home economies were emerging markets in 2015. China, for example, remains the largest OFDI country among all emerging markets, and the second largest among all home economies in 2015 (Chaisse, 2017). Figure 1 shows the number of EMNEs in Fortune Global 500 from 1995 to 2017, increasing from 69 (41 from BRIC) in 2007, when the springboard view was introduced, to 164 from all emerging economies (134 from BRIC). EMNEs have also changed the IB research landscape. As Figure 2 shows, there has been steady and remarkable growth in EMNE research since 1990, growing more notably since 2007. The number of articles published in major IB and management journals1 has also more than doubled from 2007 to 2016. The springboard view has been one of the top four theories used to study EMNEs,2 along with institution theory (including institution-based view), resource-based view (including dynamic capability), and OLI paradigm (see review by Luo & Zhang, 2016). Other notable theories previously used include organizational learning, social capital, resource dependence, transaction cost economics, network/alliance, and internationalization process. International springboard is a global strategy to improve a firm’s global competitiveness and catch up with established and powerful rivals in a relatively rapid fashion through aggressive strategic asset- and opportunity-seeking, and by benefitting from favorable institutions in foreign countries. By pinpointing such distinctive motives and prescribing unique international growth trajectories, the springboard view offers a succinct case for new theoretical advancements in the theory of MNE in general, and has emerged as a rich foundation to analyze the unique parameters of EMNEs in particular. The central premise of the springboard view is that these firms use international expansion as a springboard to (1) acquire strategic resources to Figure 1 Number of emerging market MNEs in Fortune Global 500, 1995–2017. (Color figure online) Journal of International Business Studies A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 131 45 41 40 35 30 30 25 23 20 20 15 12 10 5 0 18 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 3 0 1 2 1 3 0 0 1 20 25 20 10 3 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Figure 2 Articles on EMNEs in major IB journals (1990–2016). compensate for their capability voids, (2) overcome laggard disadvantages, (3) exploit competitive advantages and market opportunities in other countries, (4) alleviate institutional and market constraints at home and bypass trade barriers into advanced markets, and (5) better compete with global rivals with augmented capabilities and improved home base after strategic asset acquisition (Luo & Tung, 2007). These yardsticks may apply too to some advanced country MNEs that share strategic asset-seeking motive, home base’s central role, and environmental constraints at home. Surely, country of origin matters, and complete homogeneity between MNEs from different economies does not exist. Among EMNEs, not every firm would necessarily assign the same weight to each of the above goals, and each OFDI project may emphasize different goals. However, there is a pattern of strategic intent behind the firms’ overarching globalization that involves these goals that can be accomplished through the springboard act. That is, they systematically and recursively use international expansion to better equip themselves to compete against global rivals, reduce vulnerability to home institutions, and fortify their home base to further catapult, domestically and internationally. The springboard view remains important. First, despite growing counter-globalization trends in some countries that undoubtedly inject uncertainty into the future of globalization, it is difficult to envisage a future where SMNEs will retrench from their international expansion activities. While the US may be turning its focus inward, most other countries are not. Second, evidence reinforces the logic that many SMNEs’ recent acquisitions are designed to repatriate high-end, world-class technology, advance their R&D skills, bolster their innovation, upgrade their capabilities, and augment their ownership of technology (Forbes, 2016). Even some advanced economy SMNEs share similar strategic pursuits, acquiring critical assets from other advanced economies and even from emerging economies to bolster their home country capability portfolio, a pattern highlighted as knowledge-seeking OFDI (UNCTAD, 2017: 27–29). Third, emerging economies will play a bigger role in shaping global norms and institutions that underpin the world economy. The fact that the Trump administration is no longer committed, or does less, to uphold the global economic order may make room more quickly for some leading emerging economies to assume this mantle. The BRIC countries that have benefitted immensely from the open global economy appear eager to fill the new void in global economic governance. EMNEs will serve as a key player in this pursuit. We need new insights that can further the springboard view. The springboard view needs both broader and narrower contextualization – broader in the sense that SMNEs are not limited only to EMNEs or developing country MNEs in general but can apply to some newly industrialized country MNEs (e.g., new MNEs from South Korea, Israel, Taiwan, or Singapore) and advanced country MNEs (AMNEs, hereafter),3 and narrower in the sense that Journal of International Business Studies A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 132 not every EMNE act in a springboard fashion. As noted in our original article (2007) and reported by UNCTAD (2017), EMNEs follow a dual path, investing in developed (more on strategic asset-seeking) and developing (more on market-seeking or natural resource-seeking, which involves less a springboard act) economies. We need nuanced understanding of challenges that confront SMNEs in the form of organizational complexity – within group variance and heterogeneity, different institutional and market conditions at home, susceptibility to regulatory requirements at home and abroad, evolutionary changes of these firms, and various types of organizations. Although our original piece presented the internal and external forces that stimulate EMNEs to spring, the article did not delineate in detail the competitive strengths and weaknesses that characterize these firms in comparison with AMNEs. In the present article, we will discuss this to enable us to better grasp the ownership advantages and disadvantages of EMNEs. We will also speculate on how these firms continue their growth ex post springboard. To this end, we will later introduce an upward spiral concept – that is, they begin with inward internationalization, then aggressively conduct OFDI, transfer strategic assets to home, accentuate home-centered capability upgrading, and successively re-catapult globally with stronger capabilities. We will tackle some of these issues within the springboard context, including our suggestions for future research to address them. THEORETICAL INSIGHTS OF THE SPRINGBOARD PERSPECTIVE We suggested (Luo & Tung, 2007) that EMNEs systematically and recursively use international expansion as a springboard to achieve two central objectives – acquire critical resources needed to compete more effectively against their global rivals at home and abroad and to reduce their vulnerability to institutional and market constraints at home, among other motives. These efforts are systematic in the sense that springboard steps are deliberately designed as a grand plan and a longrange strategy to establish more solidly their competitive positions in global marketplace. They are recursive in the sense that such springboard activities are recurrent (e.g., a series of OFDI activities over a period of time with each investment leveraging different strategic assets they acquire or focusing on different strategic intent such as Journal of International Business Studies market opportunity-seeking) and revolving (i.e., outward activities are strongly integrated with activities back home). Elucidated previously were also the reasons and forces that prompt EMNEs to spring, unique strategic behaviors that manifest the springboard act, fundamental challenges involving the act, as well as a typology that captures the variance of EMNEs along ownership types and global diversification. The paradigm was labeled ‘‘springboard’’ for two reasons. One, the firms’ overwhelming goal is to use international expansion to augment their capabilities and competence portfolio so as to further take off to a new height in global competition. This endeavor is intended to help them, after capability catchup, to leapfrog from their global newcomer or latecomer status and to spring further along in global competition. International expansion provides a better and faster alternative to consummate their capability portfolio than other choices. Acquired strategic assets such as technology, brands, and global consumer base complement their mass manufacturing skills and cost effectiveness, resulting in additional synergies for them. International expansion, not domestic expansion, functions as a take-off and flexible board, endowing them with great opportunities in acquiring critical assets they need (often via M&As in advanced economies) and appropriating market opportunities. The ‘‘springboard’’ is flexible in a sense that these MNEs benefit from multiple gains and options, depending on their original intent and destined host countries, ranging from institutional arbitrage and barriers bypassing to capability acquisition and market extension. Underlying such intentions is to make them competitively sturdy on the global stage. This flexibility is in part attributed to new global landscapes such as the availability of global open resources and increased M&A opportunities, willingness of AMNEs to share, sell or spin off their key assets, technological changes and advancement, and global connectivity and integration. The second reason behind the label is that international expansion supplies EMNEs with not only opportunities and capability augmentation (hard skills) but also global visions, views, insights, and experience (soft skills) needed in international competition. They cannot leap, jump, and spring in global competition if they stayed home. Recent studies confirm that successful EMNEs tend to maintain strong entrepreneurial leadership (Cui, Meyer, & Hu, 2014; Rui & Yip, 2008; Yiu, Lau, & A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 133 Bruton, 2007; Zhou, Barnes, & Lu, 2010) and that internationalization brings in global visions for both foreign subsidiaries and parent firms, and such visions buttress business growth at home and abroad (Al-Aali & Teece, 2014; Brouthers, Nakos, & Dimitratos, 2015; Wang et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2010). A global springboard furnishes new impetus, new visions, and new horizons, which, along with newly acquired capabilities, enables these firms to attain higher levels of competence and a stronger home base, both of which then fortify their global spring. EMNE executives have to skillfully maneuver their strategic choices within their domestic institutional contexts. Firms that compete and upgrade successfully are often led by executives who have a sharp global vision yet with pragmatic measures to tap into foreign markets that provide resource-seeking or market-seeking opportunities (Luo & Tung, 2007). The springboard view sheds light on the firms’ unique behaviors, motives, and activities, integrating inward internationalization (experience, networks, absorptive capability, and activities) and outward internationalization and explicating leapfrog trajectories to mirror the springboard act. It explains that springboard firms tend to internationalize rapidly, not incrementally. Parachuting internationalization, a notion that has been introduced by Fang, Tung, Nematshahi, and Berg (2017), parallels springboarding in this regard by showing that firms can successfully enter into psychically distant markets through the adoption of creative strategies, such as ‘‘correct positioning, swift actions, and fast learning.’’ As global latecomers, they accelerate their pace of internationalization so as to catch up with that of incumbents. This view suggests that while organizational learning and international experience or evolution are still important to them, these firms are often radical in bypassing cross-country, cross-region distances (cultural, institutional, economic, and geographic). Often, they first venture into advanced markets. Similarly, their initial commitment tends to be large and does not necessarily involve many small steps. Also, departing from the conventional wisdom of control, EMNEs tend to recruit host country nationals as members of the senior management team rather than deploying parent country nationals, and tend to delegate more power to foreign subsidiary managers than traditional MNEs (Wang et al., 2014). The springboard discourse elaborates on firm-, market-, and institution-level forces that prompt or support springboard behaviors. Contextual differences also exist between the new vis-à-vis traditional views toward MNEs. Finally, this view explains, though briefly, the challenges to both EMNEs in general and to springboard behaviors in particular. For instance, poor accountability and weak corporate governance may tarnish the process and outcome of springboard endeavors. They face enormous post-springboard, post-acquisition difficulties, ranging from building effective working relationships with host country stakeholders, reconciling disparate national- and corporatelevel cultures, retaining local talent, organizing globally dispersed complex activities, to integrating home and host country operations. The springboard view has been supported and validated by numerous studies. For example, Gubbi, Aulakh, Ray, Sarkar, and Chittoor (2010) analyzed 425 cross-border acquisitions by Indian firms during 2000–2007, confirming that international acquisitions facilitate internalization of tangible and intangible resources that are both difficult to trade through market transactions and take time to develop internally. The magnitude of value created will be even higher when the target firms are located in advanced economic and institutional environments. Kedia, Gaffney, and Clampit (2012) demonstrate that the EMNEs’ ability to overcome their inherent disadvantages as latecomers relies heavily on their capability to seek knowledge outside of their home country through OFDI and that such knowledge-seeking OFDI is not based on the traditional asset-exploitation model of FDI, but rather focused on asset-augmentation. Li, Li, and Shapiro (2012) confirmed the notion that an important catchup strategy for EMNEs is to invest in developed markets that have industry-specific comparative technological advantages. Bae, Purda, Welker, and Zhong (2013) demonstrate that EMNEs use international expansion as a way to circumvent the institutional and market constraints they face at home and to acquire the resources they need to compete globally. Their findings, based on a longitudinal analysis (1991–2009) of credit rating data by Standard & Poor’s, also confirmed our proposition that EMNEs use internationally known market intermediaries to mitigate their poor perceptions of weak governance, transparency, and accountability. Kothari, Kotabe, and Murphy (2013) and Kotabe and Kothari (2016) employed an inductive approach by performing a historical analysis of Chinese and Indian MNEs, and concluded that EMNEs’ foreign expansion is driven by both assetseeking (acquiring resources and absorbing them to Journal of International Business Studies A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 134 build their own advantage) and opportunity-seeking (finding foreign market niches and entering into markets untapped by AMNEs) motives. More recently, Satta, Parola, and Persico (2014) compared EMNEs with AMNEs, stressing the important role of inward FDI in boosting EMNEs’ OFDI. They also find that the effect of psychic distance is not significant to EMNEs. Also comparing EMNEs with AMNEs, De Beule, Elia, and Piscitello (2014) conclude that EMNEs acquire less control than AMNEs, especially in high-tech industries, while institutional distance in trade and investment freedom effectively increase the probability for EMNEs to undertake full acquisition as opposed to AMNEs. Focusing on autonomy delegation to foreign flagship subsidiaries by Chinese MNEs, Wang et al. (2014) suggests that decentralization is often used to facilitate the springboard act in assetseeking and opportunity-seeking. Based on a sample of 1004 cross-border acquisitions undertaken by Indian firms during the period 2000–2010, Gubbi and Elango (2016) find that seeking critical assets is a key motivation for EMNEs to make acquisitions in foreign markets, especially those in developed economies. Gaffney, Karst, and Clampit (2016) compared BRIC country MNEs with UK MNEs, confirming that, in order to facilitate the transfer of critical or tacit assets during cross-border acquisitions, EMNEs pursue higher levels of equity participation or full acquisition when targets are based in locations that are institutionally distant in terms of knowledge protection. A major limitation of the springboard view, and essentially most views toward EMNEs, is a deficit in articulating how exactly EMNEs differ from AMNEs in their respective ownership advantages before, during, and after expanding internationally. As Ramamurti (2012), Cuervo-Cazurra (2012), Hennart (2012), and Verbeke and Kano (2015) stated, EMNEs do possess some ownership advantages, but these are different from the ones we have been trained and conditioned to see in AMNEs. Little is known about how such home-built or home-grown ownership advantages can be transferred and utilized as they go global. The springboard view suggests both opportunity-seeking (e.g., exploiting ownership advantages and market opportunities in other developing economies) and asset-seeking (e.g., acquiring critical capabilities from mature MNEs in advanced economies). Explanations are needed regarding what such advantages are and how they are leveraged. Two, the springboard view emphasizes the importance of the home base in Journal of International Business Studies both impelling capability augmentations via the acquisition of foreign strategic assets and re-catapulting global expansion later from this base by leveraging upgraded capabilities. This view stops short of fully elucidating reinforcing and successive linkages, processes, and mechanisms between home base and global expansion. One particular challenge for EMNEs pertains to their weak skills in organizing the transfer, diffusion, and integration of what they have acquired abroad with what they already possess at home. To compensate for the firm’s competitive disadvantage, it is essential to integrate and organize capabilities ex post foreign acquisitions. Although it is beyond the scope of the springboard view, post-springboard integration or orchestration is critical to understanding the growth of EMNEs. Three, the springboard perspective ignores soft power deficits of many EMMEs that can affect the host country nationals’ attitudes and policies toward investors from emerging markets. Four, the springboard view suggests that there are multiple goals and motives underlying SMNE expansion, but why and how to bundle these multiple objectives has yet to be explained. For example, it is possible that a firm may simultaneously pursue market opportunities and institutional arbitrage from the same OFDI project. Acquiring foreign strategic assets may be comingled with capability acquisition and enhancement of both global and home reputation. A more comprehensive explanation of interconnectivity of multiple goals and acts is needed in the literature. Finally, the view does not adequately address the evolution of SMNEs. When and where will they be path dependent or otherwise path departure as they grow? Further, it is incorrect to assume that organizational learning and foreign experience are not important to them. Viewed from a long-term perspective, SMNEs are and will continue to be evolutionary. COMPARING THE SPRINGBOARD VIEW WITH OTHER THEORIES Table 1 offers a comparison of the springboard view with other major perspectives toward EMNEs such as the LLL (linkage, leverage, and learning) framework, unique advantage logic, and institutional arbitrage logic, which are a set of prevalent EMNEspecific perspectives (Luo & Zhang, 2016). The springboard view and the LLL framework (Mathews, 2002, 2006) both recognize an accelerating trajectory of some emerging market firms in A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 135 Table 1 Comparing springboard with other views on EMNEs Springboard perspective (SP) Key points SP focuses on the logic that EMNEs systematically and recursively use international expansion as a springboard to achieve multiple strategic goals such as acquire strategic assets, compensate for their disadvantages, exploit unique strengths, and cope with home institutions Home market exploitation and global competitiveness catchup motivate them to acquire strategic assets and to springboard Linkage–leverage–learning framework (LLL) Ownership (but unique) advantage logic (OA) Institutional arbitrage logic (IA) The 1st ‘‘L’’ draws attention to how Asian MNEs (e.g., from Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and South Korea) overcame resource deficiencies by accessing superior external resources via linkage (partnerships). The 2nd ‘‘L’’ refers to the ways that links with incumbents can be leveraged. The 3rd ‘‘L’’ refers to the learning resulting from repeated application of linkage and leverage processes (see Mathews, 2002, 2006) LLL focuses on very large Asian firms from newly industrialized economies EMNEs have ownership advantages before going global yet these advantages may differ from AMNEs, such as deep understanding of customer needs, operating in difficult environment, low-cost ability, right feature-price mix (Dunning, Kim, & Park, 2008; Ramamurti, 2009; Rugman, 2009) These advantages are contextspecific, reflecting home country or country-of-origin conditions (Narula, 2012; Ramamurti, 2012) Escapism or exit view: EMNEs go global to distance themselves from or avoid weak institutional environments at home (Boisot & Meyer, 2008; Witt & Lewin, 2007; Yamakawa, Peng, & Deeds, 2008). It is especially so when they invest in advanced markets where property rights are better protected Exploitation view: EMNEs are adept at competing in other developing countries with weak institutions because they are accustomed to, and knowledgeable in handing, such hardship and uncertainty. They are superior in surviving in such conditions (CuervoCazurra & Genc, 2008) LLL is less concerned with institutional conditions at home and host countries A firm’s home market growth plays a larger role in SP than in LLL Acquiring strategic assets to compensate for the firm’s weaknesses is key per SP, and less so per LLL SP explains logic of radical expansion such as M&As SP addresses a continuous and upward spiral link between home country and foreign expansion; LLL doesn’t deal with it Undoubtedly, every firm must possess certain firm-specific advantages (even compete locally), yet OA needs more explanation on what specific advantages they have, and how much such advantages are valuable and transferable across borders SP states that springboard act is a critical and special capability of EMNEs, underpinned by their sharpened firm-specific ability in intelligence, networking, entrepreneurial leadership, and speed. OA should embrace this SP acknowledges both advantage leveraging especially for market-seeking and disadvantage compensation via strategic assets and capability acquisition; OA focuses mainly on the former IA focuses on the logic that EMNEs can leverage institutional arbitrage by utilizing their skillset in adapting to institutional pressure that is difficult to Western firms, or just benefit from better institutional environment overseas SP addresses the institutional arbitrage too but it also explains other unique motives and behaviors of EMNEs. SP assumes that springboard act is intended to achieve multiple strategic goals and benefits beyond institutional IA has to reconcile the coexistence of escapism and exploitation views for diversified firms investing in both developed and less developed countries IA is laudable in bringing in the unique institutional insight but it warrants to integrate this insight with market-seeking and capability-seeking act Distinctions Journal of International Business Studies A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 136 Table 1 (Continued) Springboard perspective (SP) Linkage–leverage–learning framework (LLL) Ownership (but unique) advantage logic (OA) Institutional arbitrage logic (IA) Both intend to address the question of how non-Western firms can become competitive through international expansion Both views recognize that the influential monopolistic advantage logic may not apply well to normal run of these firms Both recognize the use of networks and partnerships For foreign market opportunity-seeking EMNEs, both SP and OA state the importance of advantages in products, marketing, price, and technology In the long run, springboard will augment and create more ownership advantages for EMNEs. Virtually all EMNEs aim to catch up and be more competitive both home and abroad Relational capability as ownership advantage can be a common ground shared by SP, OA, and others Both IA and SP delineate links between home and host conditions Both IA and SP acknowledge that home governments and their policies matter. Promarket reforms and property rights protection at home influence EMNEs’ OFDI Both IA and SP need to offer more nuanced insights into internal differentiations within EMNEs, even from the same home country, e.g., who would escape, and when and where to go? Complementarity internationalization, the use of linkages or networks in this pursuit, and the quest to overcome resource deficiencies by accessing superior external resources. The LLL framework focuses on large Asian MNEs from newly industrialized economies such as Singapore, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, which embarked on massive OFDI in the early 1990s in response to their small home market base, increased domestic labor costs, and appreciation of home country currencies. Inherently, they differ from numerous EMNEs that began large-scale internationalization a decade later with a different dominant intent (e.g., bolster and leverage their home base by upgrading capabilities through global expansion and M&As for the latter). Also, the LLL framework does not deal with institutional pressures in home and host countries.4 Ramamurti (2009, 2012), Rugman (2009), and Dunning et al. (2008) argue that EMNEs still have some ownership advantages before going global but such advantages may differ from those possessed by AMNEs. The former, for example, may have some potent edge in understanding customer needs, operating in difficult environments, maintaining a low-cost position, and offering right feature-price mix. These advantages, as reminded by Ramamurti (2012) and Narula (2012), are context-specific, reflecting the home country or country-of-origin conditions, which imply low transferability to contexts that are hugely dissimilar. This ownership (but unique) advantage logic accords with the Journal of International Business Studies springboard view in that both perspectives recognize a likelihood that some unique advantages possessed by EMNEs are context-specific (e.g., products offered to mass middle-class or belowmiddle-class consumers), thus constraining transferability of these advantages. Relational capability as EMNEs’ ownership advantage is also consistently acknowledged by these views. The springboard view suggests that EMNEs seek to catch up and be competitive in both domestic and international markets. Ultimately, the springboard act will augment and create more ownership advantages in the aggregate which allows the firm to better compete. Nevertheless, the springboard view sees OFDI as a flexible board to jump (capability upgrading), augment (compensating disadvantages at home), and re-catapult domestically and internationally to new heights. It also illustrates that the springboard act itself is a critical and special capability, involving a firm’s adeptness in business intelligence, foreign networking, and entrepreneurial leadership (Luo & Tung, 2007). Rui and Yip (2008) suggest that an EMNE’s strategic intent that goes beyond the conventional logic of leveraging ownership advantage is an important driver of their OFDI decisions. Sun, Peng, Ren, and Yan (2012) analyzed 1526 cross-border M&As by Chinese and Indian MNEs, and found that comparative ownership advantages in areas such as national factor endowments, institutional constraints, and industrial supportiveness are also significant drivers of their M&As. A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 137 Institutional arbitrage logic encompasses passive (escapism) and active (exploitation) notions. An escapism notion stresses that EMNEs go global in order to avoid weak institutional environments at home (Boisot & Meyer, 2008; Witt & Lewin, 2007; Yamakawa et al., 2008). They tend to do so by investing in advanced markets where property rights are better protected and institutional conditions are more conducive to business development. The exploitation view highlights that EMNEs are adept at competing in developing countries with weak institutions because they are accustomed to, and knowledgeable in handing, such hardship and uncertainty. They are superior to AMNEs in surviving under such conditions (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008). This logic is commendable in so far that it conveys institutional insights, but it is limited in its ability to combine institutional logic with market-seeking and capability-seeking rationality. EMNEs globalize not merely as a response to institutional forces but as a strategic act for capability augmentation and market-seeking. The springboard view thus acknowledges more strategic motives and traits than does institutional arbitrage logic. Future research in institutional arbitrage should seek to unify both passive and active notions for the same firm when it diversifies its investments in varying types of economies wherein both exploitation and escapism benefits can concurrently ensue. The springboard view and institutional arbitrage both explicate the links between home and host country conditions, acknowledging that home country governments and their policies are important to EMNEs’ expansion. Nonetheless, both views need further development in illuminating dynamic changes – how the firm evolves from its initial pursuit of institutional arbitrage to subsequent pursuit of market opportunities, for example. It is unlikely that an EMNE will remain focused solely on institutional arbitrage without later seeking for host country market opportunities and/or resource opportunities. Table 2 summarizes the comparison between the springboard view and other IB theories.5 This comparison allows us to see abundant complementarities and differences. Contrasting to the eclectic paradigm (Dunning, 1981, 1988; Rugman, 2009), the springboard view does not see the possession of conventional ownership advantages such as proprietary technologies and market power as a precondition to go global, and it focuses instead on acquiring critical capabilities that compensate for the firm’s competence void. The springboard view realizes the importance of internalization, but it interprets internalization mainly as transferring acquired foreign strategic assets back home and subsequently catapult at and from home with solidified capabilities. That said, the springboard view and the OLI paradigm are highly complementary in that springboard is not just an act but a firmspecific capability that reflects the firm’s ability in identifying, negotiating, acquiring, and combining skills. As explained later, SMNEs do possess unique ownership-specific advantages, and thus the explanatory logic of ownership- or firm-specific advantages works well for springboard firms. In post-springboard operations, MNEs will increasingly engage in internalization and orchestration, and will use their home as the base platform for integrating their globally dispersed activities. Finally, location advantages (e.g., Porter’s diamond forces) are relevant to SMNEs pursuing overseas market opportunities and global economy of scale. Institutional arbitrage opportunities can be considered as special location advantages as well. The springboard act is an evolving process but it differs substantively from the conventional logic of internationalization process represented by Johanson and Vahlne (1977, 2009). The springboard view does not presume that a firm’s expansion process necessarily involves a series of incremental steps nor does it postulate that a lack of knowledge and experience is a big obstacle to this expansion. It does not base its premise on an assumption that the firm enters and furthers new markets via progressively greater psychic distance. While the springboard view recognizes the learning and experience effect, it does not correlate the springboard moves with the accumulation of host country-specific market experience. These differences are easy to understand because SMNEs are compelled to overcome their global latecomer disadvantages, while their dominant intent is to acquire strategic assets. Increased global connectivity also attenuates cultural and geographic divides, while amplified availability of global open resources and intermediary resources lessen the necessity of path dependence in the internationalization process. That said, springboard moves do involve organizational learning in globalization. Global experience is and will continue to be one of the major determinants for these firms’ global success during their post-springboard expansion. Much of such experience is tacit and firm-specific (Buckley et al., 2016). The springboard view meshes well with internalization theory (especially the new internalization Journal of International Business Studies A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 138 Table 2 Comparing springboard perspective with other IB theories Springboard perspective (SP) Major arguments EMNEs use int’l expansion as a springboard to acquire strategic resources, reduce home institutional constraints, overcome laggard disadvantages, and compensate for their weaknesses via a series of aggressive measures like M&As SP explicates unique traits, motives, strategies, fostering or constraining factors, and risks and challenges involving springboard behavior OLI paradigm (OLI) Internationalization process theory (IPT) Internalization theory (IT) RBV/dynamic capability (RBV and DCT) OLI (O) emphasizes possession of proprietary or ownership-specific resources, market power, or monopolistic advantage as the prerequisite for going global OLI (I) suggests that internalization serves as a unified, integrated intrafirm governance structure due either to no external market or to deficiency and imperfection of such market for intermediate products needed by MNEs OLI (L) argues that MNEs locate manufacturing activities in countries that are the most advantageous for cost (e.g., labor) and revenue (e.g., market demand) considerations The Uppsala model sees int’l expansion as a process involving a series of incremental steps, assuming that lack of knowledge and experience is a big obstacle to this expansion Incrementally and farsightedly accumulated knowledge and experience on countryspecific market, practices, and environment increases the firm’s local commitment and reduces uncertainty The firm enters and furthers new markets via progressively greater psychic distance. Commitment increases as both experiential and objective knowledge increase Internalization unfolds via a unified, integrated intra-MNE governance structure, which is even more critical when market is inefficient Firms choose the least cost location for each activity they perform, and they grow by internalizing markets up to the point where the benefits of further internalization are outweighed by the costs MNEs internalize the market in knowledge within the firm. Proprietary knowledge flows within the firm are superior New IT focuses on the dynamics of int’l governance, whereby value creation hinges on successful knowledge recombination and governance choices The fundamental principle of RBV is that the basis for a competitive advantage of the firm lies primarily in the development of the bundle of resources that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and nonsubstitutable. Such resources should be heterogeneous in nature and not perfectly mobile DCT addresses a firm’s ability to build, integrate, and reconfigure competencies to cope with rapidly changing environments. It underscores internal processes, routines, and practices for coordination, integration, learning, adaptation, and reconfiguration Dynamic capability requires a strong base of established capability and an ability to efficiently deploy, evolutionarily reconfigure, and continuously upgrade them Unlike OLI, SP does not see possession of conventional ownership advantages such as proprietary technologies, market power, and global brands as a precondition to go global. Instead it centrals on going global to fill in these areas they are weak SP assumes that global markets for intermediaries and open resources have improved. EMNEs internalize, less for addressing imperfection of intermediary markets but more for integrating major capabilities they acquired back to home, then furthering their global competitiveness SP doesn’t assume that how country location advantages such as labor costs are central to EMNEs’ decisions but institutional environment, resources availability, and mass markets matter Per SP, distance matters less for EMNEs due partly to global connectivity and partly to their strategic intent Springboard act is often radical and aggressive, not incremental, because EMNEs need to circumvent laggardness and lateness visà-vis established global rivals Path dependence (including experiential knowledge) and sequential foreign entry or OFDI are strong logic for IPT, but much less so for SP Per IPT, an initial option involves a small amount of OFDI used to explore opportunities in a host country. Once enough experience is gained and the option class for further investment, the MNE will increase its commitment to exploit more opportunities. EMNEs show a less propensity to this pathway SP emphasizes how MNEs internationally expand in order to compensate for their capability weaknesses via capability acquisitions, while IT focuses more on leveraging a firm’s strengths (both internal governance and firmspecific advantages) Key intermediary product (including technology) market conditions and global open markets for key resources have noticeably improved since internalization theory was introduced, spurring springboard in the 21st century Home market or home base plays a central role in SP for the MNE’s overall growth and development, which is not the focus of IT Home country institutions and institutional arbitrage is another central element of SP, but less so in IT SP focuses on entrance stage of global expansion, explaining what motivate EMNEs to go global in a radical and risk-taking way, whereas RBV and DCT discuss what are and how to build sustained distinctive capabilities and competitive advantages SP applies only to EMNEs going global and undertaking OFDI; RBV and DCT apply broadly to all kinds of firms in various contexts although they are not specifically IB theories Global dimensions of RBV and DCT are not explicitly articulated, but there exists a great potential to extend them to global competition and global competitiveness RBV and DCT remind us that not all resources and capabilities can be acquired or attained by EMNEs via crossborder M&As. Even IF they do, many deeply embedded processes and routines associated with such capabilities within the firm are sticky, tacit, and nontransferable Differences Journal of International Business Studies A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 139 Table 2 (Continued) Springboard perspective (SP) OLI paradigm (OLI) Internationalization process theory (IPT) Internalization theory (IT) RBV/dynamic capability (RBV and DCT) Springboard is not merely an act but a unique capability that is firm-specific, involving business intelligence, acquisition capability, and combinative skills In post-springboard operations, EMNEs will increasingly engage in internalization and orchestration, and will use home as the base platform to be integrated with their globally dispersed activities Location advantages (e.g., Porter’s diamond factors) are relevant to EMNEs pursuing overseas market opportunities and global economy of scale. Institutional arbitrage opportunities are viewed as location advantage too While SP deals less with evolutionary processes, both SP and IPT acknowledge the importance of organizational learning in globalization International expansion can be regarded as an optional window permitting MNEs to gain more tacit knowledge about int’l expansion and competition in general, and the host country in particular. IPT (more directly) and SP (more indirectly) both share this tenet Global experience is, or will be, one of the major determinants for EMNEs’ global success during their post-springboard expansion Both IT and SP addressed resource recombination. Integration and orchestration within the MNE are critical in both theories Both IT and SP view internationalization as a dynamic, multifaceted process, whereby strategic governance modes are subject to change over time; Both IT and SP (upward spiral) articulated the importance and process of internalized governing of global value chain Both explained capability and resource flows within a globally differentiated yet centrally coordinated and integrated intra-MNE system EMNEs must build their own distinctive capabilities (RBV) and dynamic capabilities (DCT), especially after springboard. The ultimate goal of EMNEs is to solidify their global competitiveness The notion of capability deployment, transfer, alignment, and upgrading is profoundly critical to all MNEs, EMNEs included, in a global setting. Postspringboard success rests squarely on such deployment, transfer, integration, and reconfiguration A successful springboard act involves well-designed global planning and opportunity identification skills, and execution of such plans requires distinctive capabilities, routines, and processes both overseas and at home Complementarity theory) in multiple regards. Both explain the importance of resource recombination and view internationalization as a dynamic, multifaceted process (see Narula & Verbeke, 2015; Verbeke & Kano, 2015). Both articulate the importance of orchestrating an evolving process and internalized governing of global value chain (see Kano, 2017). Nonetheless, the springboard view emphasizes how MNEs expand in order to compensate for their capability weaknesses through aggressive capability acquisitions, while internalization theory focuses more on leveraging a firm’s strengths (both internal governance and firm-specific advantages). Market conditions (including markets for intermediary products and technologies) in the two different periods of time when internalization and springboard perspectives were introduced, respectively, noticeably differ too. Global open markets for key resources are profusely improved in the 21st century. Also, home market and home base play a central role in EMNEs’ overall growth and long-term development, and such a role is not the focus of the internalization logic. Finally, home country institutions, together with offensive or defensive arbitrage arising from institutional differences between home and host countries, is another central element of the springboard perspective, which, however, is not an emphasis of the internalization theory. The springboard view shares a key tenet of dynamic capability theory (DCT) in that a firm’s sustained growth depends on its sharpened ability to integrate, diffuse, adapt, and reconfigure its key resources to cope with changing environments. The central goal behind springboard is to augment and upgrade the firm’s critical resources and capabilities, which aligns with DCT in global competition. More recently, Teece (2014) added that dynamic capability should be coupled with good strategy as a necessary condition to sustain superior performance in fast-moving global environments. The springboard act is a deliberate strategy for capability catchup and upgrading with the objective to be savvy in competing against AMNEs. As more research is needed to address post-springboard activities and processes, we see an upright convergence between DCT and post-springboard orchestration of globally dispersed operations. The ultimate goal of SMNEs is to fortify their global competitiveness, and to this end the notions of capability composition, redeployment, and reconfiguration are cogent to diagnose post-springboard organizing, managing, harnessing, and harvesting. Nonetheless, the springboard view does not carry broad implications as does DCT or RBV that applies to a wider range and kinds of firms in various contexts. It also differs from DCT or Journal of International Business Studies A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 140 RBV in that the latter requires a strong base of established capabilities. It would be fascinating to probe how springboard strategies, coupled with the firms’ resilience, buttress their subsequent dynamic capabilities evolutionarily, and how they transform their acquired strategic assets and resources later into a bundle of distinctive capabilities that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable. We know little on routines, processes, and mechanisms, which may be deeply embedded within the firm, that propel such a transformation. UNDERSTANDING THE PECULIARITY OF SPRINGBOARD MNES Despite growing inquiries on SMNEs, the majority of research addresses internationalization motives, entry strategies, and institutional effect (see review by Luo & Zhang, 2016), while a big lacuna remains on studies of their unique strengths and weaknesses. Ramamurti (2012) and Cuervo-Cazurra (2012) state that emerging market firms must possess some unique ownership advantages before and during their internationalization, but, as they point out, we know little about what exactly these advantages or disadvantages are. In this article, we submit that unique advantages (realized or potential) of springboard firms lie in amalgamation, ambidexterity, and adaptability (AAA). It is reported, for instance, that EMNEs have a competitive edge over AMNEs in cost and speed advantages (Guillén & Garcı́a-Canal, 2009; Ramamurti, 2012; Sun et al., 2012; Wells, 1983), learning and linkage advantages (Elango & Pattnaik, 2007; Govindarajan & Ramamurti, 2011; Mathews, 2006; Zhou et al., 2010), and their ability to transform institutional disadvantages into advantages (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008; Gaur, Kumar, & Singh, 2014; Hoskisson et al., 2013). We echo these observations, but underlying these advantages, we suggest, are these firms’ deeper abilities in amalgamation, ambidexterity, and adaptation. These capabilities are not entirely new or applicable only to SMNEs. We caution too that these firms vary among themselves in such capabilities. Amalgamation Amalgamation means an MNE’s ability to creatively improvise and combine all available (internal and external) resources (including those purchased from global open markets), creating impressive price–value ratios suited to mass global and domestic consumers who are generally cost-sensitive. Journal of International Business Studies These firms are able to compete by creatively assembling and integrating the open and generic resources they possess or purchase; that is, they are astute in distinctively identifying, leveraging, and combining available resources, both external and internal, to create some temporary competitive advantage in cost, speed, and price–value ratios (Luo & Child, 2015). The springboard act helps amalgamation via identifying and acquiring key resources, exploiting market opportunities, and building global networks. Amalgamation involves identification (detecting needed resources and amalgamation opportunities), composition (combining technologies, resources, product features, and functions), and exploitation (using a mixture of competitive means such as combined low cost and extended features). The composition-based view developed by Luo and Child (2015) offers a foundational understanding of amalgamation. SMNEs generally have competitive disadvantages in global brands, core technologies, high-end customer bases, and original innovation compared with long-established MNEs from developed economies. What they are good at, however, is sharpened skills in improvising all existing and available resources, combining new product features and functions in a cost-effective fashion, and responding quickly to mass market needs (Luo & Child, 2015). Improved global open markets (e.g., applied technologies) and springboard opportunities jointly alleviate the burden for these firms to invest heavily in R&D, and in many industries enable them to skip multi-generations of technological development conducted by established AMNEs. Meanwhile, many advanced country firms specializing in industrial design, technological configurations, and modularity of technologies provide sophisticated industrial services to springboard firms. While cross-boundary, cross-sector open markets for technologies, key components, industrial design, and other key inputs facilitate this phenomenon, amalgamation actions and processes do involve some degree or fashion of creativity. It is indeed difficult for firms to sustain competitive advantages by amalgamation; however, by creatively or innovatively combining and integrating different yet suitable technologies and complementary product features and services that bring in greater convenience, experience, and values to the world’s mass middle-class and below-middle-class customers who care about price–value ratios, amalgamation can create some temporary competitive edge. Per Luo and Child (2015), composition-based strategy is manifested in compositional offering A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 141 and compositional competition. This applies to businesses that engage in springboard as well. Compositional offering occurs when a firm amalgamates an extended array of its products’ performance features and functions, as well as services for existing customers whose satisfaction increases as a result of this extension and amalgamation (e.g., one-stop for all or total business solutions). This approach works because it provides customers with amplified services, value, convenience, and time savings, yet does so at a fraction of the cost of nonamalgamated or separated functions or services. Asset-seeking springboard provides the firms with technologies and resources needed for compositional offering, while opportunity-seeking springboard extends foreign markets in which compositional offering can be harvested. The rise of open architecture or platforms that assemble and reconfigure various technologies and functions also stimulates compositional offering. Compositional competition exists when an SMNE uses a set of combined and integrated means or measures to compete against rivals (e.g., combining cost, price, product features, speed, and design-based customization), providing customers with superior price–value ratios. Compositional competition seeks to exploit opportunities associated with mass markets (middle-class, below-middle-class, and base-of-pyramid consumers). They compete on the basis of a composition of combined price, design, functionality, quality, features, volume, and services. With an exception of some large companies, many of emerging market firms do not possess global competitive advantages in areas such as technology, brand, and market power in separation, but are able to compete when composing building blocks of a competitive advantage. Springboard benefits these MNEs not only with imbuing them new resources needed for compositional competition but with more opportunities to understand and exploit global markets and to cultivate global business networks and value-chain systems imperative for compositional competition. Both compositional offering and compositional competition are underpinned by amalgamation capability. This capability overlaps with the concept of combinative capability introduced by Kogut and Zander (1992) that synthesizes current and acquired knowledge. Both concepts stress the importance of building up a dynamic perspective of how firms learn new skills by recombining their current capabilities. Both acknowledge the importance of regularities (e.g., routines, values, processes) by which members cooperate in a social community (i.e., group, organization, or network). Still, amalgamation capability focuses more on a firm’s distinctive ability to combine outside technologies, key components, specialized services, and key resources from open channels with its own resources, designs, and production so that its new product offering has better performance features, lower cost, and other improved attributes. For SMNEs, this capability pertains more broadly to the firm’s ability to exploit global resources creatively. It is also reinforced by their proficiency in bricolage – the enduring practice or experience of surviving under institutional hardship and pressure – and creating order out of whatever resources are available at the time. These firms utilize innovative methods to employ limited resources during times of uncertainty while creating conditions of stability out of chaos. These companies have mastered the art of improvisation, doing more with less, and compositionally offering or competing with a pragmatic approach that reflects their strength in understanding customer needs and cost constraints. Ambidexterity Springboard is a strategic means by which the firms capture values of ambidexterity – acquiring global resources they need and augmenting global competitiveness at new heights. Per the real option logic (Kogut & Kulatilaka, 1994), this may create option values of benefitting from both acquiring/ buying and augmentation/making. Ambidexterity is a firm’s characteristic property to simultaneously fulfill two disparate or conflicting goals that are critical to the firm’s long-range success. Luo and Rui (2009) suggest that some successful EMNEs are ambidextrous in their co-orientation, co-competence, co-opetition, and co-evolution. Co-orientation is the ability of firms to concurrently pursue short-term survival and evolving competitiveness when competing overseas. Co-competence pertains to their unique skills in utilizing transactional competence and relational competence together. Co-opetition underscores their superiority in balancing or harmonizing competition and cooperation with other business players. Finally, coevolution suggests that MNEs often perform both local compliance and local influence at the same time when dealing with institutional forces in a host country. Ambidexterity is reflective of the cultural backgrounds of MNEs from countries such as China, Journal of International Business Studies A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 142 India, and East Asia. Chinese MNEs have a long tradition in embracing harmony, cherishing trust building in business ties, and caring long-term growth in business planning. They may also be better prepared than MNEs from other countries of origin in adapting to and operating in institutionally harsh environments (e.g., weak legal system, vague property right protection, and government policy uncertainty). Their ability to thrive under hardship helps prepare them to deal successfully with the crises, make sound business decisions, compromise with business stakeholders, and sacrifice during times of extreme austerity (Boisot & Meyer, 2008; Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008; Luo & Child, 2015). Many East Asian firms, for example, have adopted the ‘‘middle way’’ as their philosophy to formulate strategies, manage organizations, and deal with external partners. ‘‘Mid-way’’ is the practice of non-extremism and a path of moderation away from the extremes of self-indulgence and selfmortification. The harmony principle from Taoism also suggests that opposite polarities are actually balanced and work together through cycles, thus creating a harmonious world. The yin–yang principle holds that opposite elements can mutually transform into each other in a process of balancing under various conditions. The spirit of this philosophy is coexistence and unity of opposites to form the whole. It thus embodies duality, paradox, unity in diversity, change, harmony, and offering a holistic and dialectical view to the world (Li, 2010). These cultural traits spur ambidexterity building both at home and abroad. Here we emphasize several advantages associated with ambidexterity beyond what prior research has already revealed such as exploitation and exploration for firms in general (e.g., Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004) as well as co-competence, coevolution, co-opetition, and co-orientation for EMNEs in particular (Luo & Rui, 2009). First, springboard allows a firm to compensate for competitive capability shortfalls via capability acquisition while capitalizing on their mass production, cost position, and other advantages via foreign market expansion. This juxtaposition enables SMNEs to balance short-term gains (market expansion by leveraging existing capabilities) and longterm competitiveness (capability catchup and upgrading). Second, institutional arbitrage harnesses both avoidance (reducing home country institutional hardship via investing in developed countries) and exploitation (utilizing their competence to survive under institutional asperity via Journal of International Business Studies investing in developing nations). Extant research tends to treat this separately (either avoidance or exploitation), which is still true for some EMNEs. But as they grow and diversify, more EMNEs seek both avoidance and exploitation under the institutional arbitrage logic. Third, a blend of imitation and innovation illustrates ambidexterity as well. It is true that many EMNEs evolve from imitation to innovation but during such transformation they perform and combine both in some creative ways. This ambidexterity, or composition of imitation, creation, and innovation, is used to develop a composition-based competitive edge and to support future innovations as the firm continues to evolve. Innovators’ products are seldom imitated in their entirety. Instead, these firms select only those aspects of the innovators’ offerings that fit their goals. In addition, the imitated technology, design, or function is often modified or improved before it becomes a part of the imitator’s offerings. SMNEs from emerging economies tend to be structurally ambidextrous – sufficiently localizing management and organization (including top management, HR, branding, R&D, distribution) of host country operations while maintaining high global integration of capability augmentation (an upward spiral concept below elucidates this). Recent studies (e.g., Wang et al., 2014) empirically confirm that corporate offices of these firms tend to delegate power to frontier subsidiaries in the springboard process. While this needs to be validated, anecdotal observations suggest that successful SMNEs are ambidextrous in concurrently and interactively performing overseas localization and home anchoritism. Adaptability Adaptability has been widely used to denote a firm’s ability to respond to a dynamic competitive environment in order to reap opportunities and neutralize threats (Grewal & Tansuhaj, 2001). Previous research has recognized the significance of strategic flexibility, resilience, or adaptability as an effective means by which to mitigate environmental uncertainty. Usually developed through a combination of flexible organizational structure, resource slack, and a diverse portfolio of strategic options, adaptability enables firms to manage and exploit uncertain and fast-occurring opportunities and threats while responding proactively to the national and international circumstances confronting them (Evans, 1991; Kogut & Kulatilaka, 1994). A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 143 We define adaptability as the organizational capability to quickly identify and garner opportunities, adapt to market and environmental changes, and compete and survive in tough conditions, over the course of internationalization. It thus captures agility, hardship surviving, and resilience. Not every SMNE excels in adaptation, of course. Some can rapidly adapt to institutional and market differences between host and home countries, but others cannot. These firms utilize their adaptability offensively and defensively. Offensively, they establish flexibility to create initiatives and seize fastoccurring opportunities in domestic and global markets. Defensively, they employ flexibility to safeguard against unforeseen environmental or market externalities, such as regulatory change, political and legal uncertainty, and market upheaval. Adaptability is ascribed in part to the firms’ strong know-how and ability to cope with uncertainty, complexity, and unpredictability given their long experience in dealing with instability and rapid pace of change in their home countries (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008). Firms become more agile under such variable conditions. Countries do differ in type, manifestation, and reason behind various market and institutional complexities and volatilities; thus not all firm-level experience in dealing with such complexity is transferable across nations. However, diversity of experience is a catalyst to enable strong international performance (Peng, 2012). Moreover, firmlevel routines, knowledge, and experience employed to navigate such complexity are valuable in curbing complexity and uncertainty in general, and institutional deterrence in particular, during international expansion (Gaur et al., 2014; Guillén & Garcı́a-Canal, 2009; Holburn & Zelner, 2010). Adaptability has also been linked to hastened learning, structural nimbleness, and entrepreneurial responsiveness, especially those that are privately owned. Rapid learning and absorptive capability are the defining features of many successful SMNEs (Rui & Yip, 2008) and one of the major strategic reasons motivating them to invest overseas (Deng, 2009). Madhok and Keyhani (2012) argue that EMNEs’ entrepreneurship helps overcome their liability of emergingness, stimulates foreign adaptability, and spurs their catchup through opportunity-seeking and capability transformation. Yiu et al. (2007) show that an EMNEs’ home country background in dealing with low resource munificence and high institutional complexity promotes their international adaptability, mediated further by the intensity of corporate entrepreneurial transformation in the form of innovation, new business creation, and strategic renewal. The emerging market MNEs’ hardship-surviving capability merits special attention – this capability includes their distinctive ability to operate and survive in an institutionally austere environment and to deal with demanding business stakeholders (e.g., governments) that may impose significant constraints over business activities in the host countries. Not all institutional hardships or barriers in new territories can be overcome by firms, but EMNEs (state and private) typically have accumulated experience in dealing with hardships before going global. This experience becomes extremely useful when they invest in countries with similar levels of governmental red tape, regulatory hindrance, policy uncertainty, weak legal protection, poor public services, and corruption. While this hardship increases transaction costs and uncertainty for all firms in the same host country, the firms equipped with hardship-surviving capability are more adaptable to such conditions and hence more resilient to institutional and competitive difficulties they encounter (Luo & Rui, 2009). UPWARD SPIRAL IN SPRINGBOARD PROCESS MNEs use international expansion as a springboard to acquire foreign critical capabilities to be combined with their home-based competence portfolio so as to catch up in global competition. Research by Gubbi et al. (2010) has validated this point. For MNEs to springboard internationally and improve their competitive strength, it is imperative that they not only exploit their limited competitive strengths such as cost advantage, speed advantage, and large-scale manufacturing, but to transfer newly acquired strategic assets and valuable knowledge back to their domestic market value-chain system (Luo & Tung, 2007). Critical to the success of this strategy is their ability to integrate domestic and foreign value-chain activities and transfer relevant strategic assets and knowledge on demand in time and space. This connection streamlines an MNE’s globally and vertically integrated valuechain activities and optimizes the exploitation of dual advantages of global resources they acquire and home power they possess. Practice suggests that many SMNEs are globally integrated (upstream or downstream) and are heavily dependent on the Journal of International Business Studies A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 144 home base for manufacturing, market share, and growth. These characteristics require that firms effectively leverage those skills they are adept at (e.g., mass manufacturing for international midand low-end markets) during foreign expansion, and subsequently incorporate newly acquired critical capabilities into the existing capability base. Here we introduce a concept of upward spiral as a new insight that helps us better understand the springboard process. An upward spiral concept suggests that MNEs grow through a deliberate selfimproving, positively reinforcing multi-stage process that consolidates and fortifies their essential capabilities needed in subsequent global competition. As Figure 3 shows, an early stage of internationalization from inward FDI to radical OFDI is primarily used to improve their capabilities. As they transfer more and more of these capabilities back to augment existing capability and resource portfolios (thereby bolstering their domestic capability reservoir), they can reconstitute as more capable global competitors. At the later stages, winning global competition becomes the end and consistent capability argumentation becomes the means. Through such an upward spiral or virtuous cycle, they become increasingly powerful on the global stage. This concept suggests that SMNEs, especially those from emerging economies, must first develop some basic skills and capabilities through inward internationalization (Stage 1) and build a basic Figure 3 An upward spiral model. Journal of International Business Studies knowledge base or experience that enables them to move radically in OFDI (e.g., M&As) to tap the most critical technologies, brands, and talents (Stage 2). While establishing and developing a foothold in carefully selected foreign markets or hubs, they transfer acquired key resources and knowledge to home operations or use these resources to compensate for what they are not good at in their quest to become more competitive at home and abroad (Stage 3). Orchestration is important in this stage. They fortify their home base (including home market competition) by exploiting their newly acquired global capabilities and resources and, through market experiment at home, further improve and upgrade these capabilities, making them more competent global players (Stage 4). Creative combination and innovation are important at this stage. The ultimate goal of SMNEs is to bolster their global competitiveness. To do so, they use their reinvigorated home base and bolstered capabilities to re-catapult globally with a new assortment of arrows in their quiver (Stage 5). They seek a larger economy of global scale associated with mass production and technologies that are extensively suitable, appropriable, and transferable to a wide range of foreign markets and mass consumers. Govindarajan and Ramamurti (2011) suggest that MNEs, especially those from India and China, undertake innovation at home before trickling up to rich countries (i.e., reverse innovation). A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 145 We note that the upward spiral is a continuous improvement process in which MNEs will continue their capability upgrading even after Stage 5. The upward spiral concept emphasizes the central role of home base for both capability upgrading and market competition purposes. This home base is more important for EMNEs than for AMNEs and those from newly industrialized economies (e.g., South Korea, Singapore, Israel, and Taiwan). One, EMNEs’ home base is large with huge potential. Two, they are savvy to the institutional (formal and informal) environment there, which is their competitive advantage. Three, their technologies, products, and even managerial styles suit home market consumers. Four, they have successfully established eco-business systems at home. Five, increased global connectivity helps them connect their home base with the rest of global operations via global value-chain activities. It is much easier today for companies to maintain connectivity than in the past. SMNEs are taking advantage of that. To ensure domestic operations can fully support the upward spiral path, orchestration capability is key. Orchestration facilitates the springboard evolution by helping convert globally acquired competencies into improved parent core dexterity in areas such as operations, production, marketing, and new product development. An upward spiral path is by no means linear nor can execution be expected to be seamless. The process may well encounter enormous difficulties as an upward spiral requires immense planning and cross-border orchestration of resources, knowledge, and capabilities. Many SMNEs are not particularly gifted in these areas. In some cases, a dearth of such skills compels some of them to purposely forego immediate integration in the first place, leaving newly acquired foreign companies or units to run their own operations independently for some period of time, then transferring back some critical resources that are ready for home-centered integration. In other words, the reintegration of global resources or skills domestically may occur incrementally over time. An upward spiral path is highly differentiated for each MNE and even within the MNE itself. First, they differ in market opportunity-seeking while building and upgrading their home-centric capabilities. Some emphasize foreign market development and expansion early in the process in conjunction with capability enhancement, while others do not. While capability upgrading is a common goal for SMNEs, they are not necessarily the same in adopting a home-centric approach. Some may place more emphasis on the central role of their home base for capability building, others may prefer a region-centric (e.g., Latin American MNEs) or hub-centric (e.g., Korean MNEs) approach that is less dependent on their home base. Further, they may differ in terms of their domestic base roles. Some may rely more on home market contributions than others. There are born-global companies and micro-MNEs from emerging markets that do not need to depend on the home base nor have to wait for the growth of the domestic market. Within an MNE, some foreign units may serve to provide the parent firm with technologies, brands, or foreign market intelligence, while other units may be instrumental in product and geographic diversification, brand image establishment, and reputation enhancement. Developing such a centrally coordinated yet internally differentiated system is not easy for any firm (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989). Pursuing these objectives requires a set of guiding principles, organizational infrastructure, and managerial procedures that underpins the above inflows and outflows. Implementing a successful upward spiral strategy requires vision and skills from management at the parent level, where executives seek and design ways to pursue opportunities globally and implement systems for continued renewal (Kotabe et al., 2011; Teece, 2014). Parents identify which assets and competencies are relevant and applicable to specific locations, determine when and where a transfer is needed, and reconfigure bundles of resources to provide the necessary organizational infrastructure for a successful transfer. In a globally dispersed network configuration, the parent is the central intelligence unit that not only looks for ways to exploit existing resources in the network, but also plays a major role in coordinating learning processes, exploring new opportunities, disseminating knowledge, and renewing core competences (Buckley et al., 2016). Unlike the commonly held view that EMNEs only transfer competencies to institutionally similar settings because domestically built resources are irrelevant and inapplicable in developed markets (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008), practice suggests that specific competencies, in whole or in part, could be applied even in institutionally more advanced environments when correctly identified. Beyond the identification of transfer opportunities, management needs to reconfigure and amalgamate existing competencies to improve applicability. Further, these parents can Journal of International Business Studies A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 146 adopt organizational systems, structures, incentive schemes, and ICT systems that help organize and ease the connection process between foreign and domestic operations.6 Competently identifying transferrable capabilities and connecting, transferring and executing are guided by leadership that reflects a clear vision. This is embodied in a global architecture that guides pursued flows of resources and capabilities over time, and blueprints requisite organizational transformations over time. The springboard strategy must be viewed as a long-range plan for improved competitiveness (Luo & Tung, 2007), and the upward spiral path exemplifies this strategy. Success is based on the pursuit of a bold vision enacted by transformational leaders who articulate strategic guidelines regarding how the organization will be sinuously molded and remolded with each iteration. This also includes setting distinct attainable goals, particularly for foreign units, that encompass a time-phased approach for capability acquisition and re-catapulting with consolidated competencies. Innovation orientation, culture, and policies are critical as well. It is doubtful that SMNEs can build sustained global competitiveness solely through the acquisition of foreign assets in an expansive and aggressive way. Success is achieved through capability upgrading and innovation, and springboard is a stepping stone to this end. Bonaglia, Goldstein, and Mathews (2007) validated this point, demonstrating that the successful growth of SMNEs depends on a combination of accelerated internationalization and organizational innovation. ORGANIZING AND MANAGING CAPABILITIES IN SPRINGBOARD DYNAMICS Needless to say, not every springboard act can succeed. It depends on firm-specific organizing and managing capabilities. Here we explain such capabilities from a micro-perspective – organizational behavior, human resources, and cultural intelligence – important yet under-researched facets of a successful springboard implementation. EMNEs often struggle to assess, manage, and integrate culture with organizational compatibility due to their lack of cross-cultural management skills. In reality, Chinese MNEs perceive their deficit in international experience, low familiarity with business norms and practices in host countries, and inability to bridge cultural differences as more Journal of International Business Studies significant challenges to OFDI than hard criteria such as R&D capability, financing, and so on (Beebe, 2006). Particularly noteworthy is the shortage of international managerial talent among many EMNEs. Even though China is the most populous country in the world, it suffers from what Farrell and Grant (2005) have characterized as the ‘‘paradox of scarcity among plenty.’’ India, soon to overtake China as the most populous country in the world, shares the same challenge to a large extent. China has greatly expanded the number of post-secondary educational institutions to provide quality managerial training in addition to sending those with high potentials to pursue advanced education abroad. Unfortunately from China’s perspective, the stay rate of foreign-educated Chinese abroad, particularly in the US, is high (World HR Lab Survey, 2004). China seeks to attract overseas Chinese to return home upon completion of their education abroad through several initiatives and over time has been successful in attracting a growing number of haigui (or returnees) to repatriate (Tung, 2016). However, in light of the intense competition among nations around the world for the same talent pool in a knowledge-based economy, there appears to be a reverse trend, known as guihai, where returnees to China have left again. Saxenian (2002) has dubbed this phenomenon as ‘‘brain circulation’’ whereby talent can flow back and forth between one’s country of origin and another country, typically an advanced economy. To successfully manage their overseas operations, MNEs cannot rely solely on the use of expatriates for cost reasons and localization requirements. While MNEs seek to hire highly qualified local nationals to work for them in their foreign subsidiaries, surveys (Tung, 2007; Leung & Morris, 2015; Tung, 2016) reveal that host country nationals are not particularly attracted to working for foreign bosses from emerging markets. The latter are perceived as ‘‘low in expert power’’ (Leung & Morris, 2015: 1045).7 This country-of-origin effect may stem from the differences in level of economic development and, in the case of China, ideologies. Many locals cannot distinguish between Chinese state-owned and private enterprises and are sometimes reluctant to work for what they perceive to be an arm of the government (Tung, 2007). Even in the case of Japan and South Korea, both OECD countries that have embarked on FDI for some time before the current crop of EMNEs, there is a persistent resistance among many Americans to A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 147 work for foreign bosses from these countries (Tung, 2014). This generally unfavorable attitude by locals in industrialized countries toward investors from emerging markets may stem from the latter’s weak soft power. The concept of ‘‘soft power’’ or ‘‘coopting’’ was introduced by Nye (1990) and affects perception of a country’s ability to lead because of its presumed legitimacy, resulting in a generally more favorable attitude by outsiders of its culture and ideology. In general, many people from industrialized countries perceive emerging markets as weak in soft power.8 An inability to attract the best and brightest local talent to work for overseas subsidiaries of EMNEs can hinder these firms’ efforts in managing abroad and contribute to ongoing problems in post-acquisition integration. An inability to fully understand the cultural norms and practices in host countries can also render EMNEs more susceptible to legal challenges. Korean MNEs, for example, have been targets of multiple law suits filed by employees, for violation of affirmative action (both race and gender discrimination) and sexual harassment allegations (Cole & Deskins, 1988; Tung, 2014). Such highprofile cases can only frustrate an emerging market’s attempt to build up its country’s soft power. Relatedly, building a positive image for both country of origin and EMNEs from these countries is a challenge. For instance, in Africa where China MNEs and the Chinese government have made substantial investments estimated at $200 billion, twice the amount from the US, some local nationals may be resentful of the investor practices of exporting virtually everything to fuel infrastructure and extractive projects in these countries (Solomon, 2017). FUTURE RESEARCH AND SUGGESTED AGENDA One complexity to examine SMNEs lies in heterogeneity among them. We noticed this issue in our original article and introduced a typology along business ownership and international diversification, categorizing these firms into world stage aspirant, transnational agent, niche entrepreneur, and commissioned specialist (Luo & Tung, 2007: 483). This, however, is inadequate to untangle the differences among the group. SMNEs from varying countries of origin and industries differ in many ways. Even firms from the same home country diverge in terms of capabilities, motives, internationalization stage, risk-taking, global scale, target markets, entry modes, and other OFDI strategies. SMNEs from emerging countries are still different from SMNEs from advanced and newly industrialized economies concerning the home market’s importance, size, and linkages as well as the home country’s institutional complexity and its effect on transnational activities. Small firms, especially those who do not have strong financial resources or who have not been able to finance their capability shortfalls (Hennart, 2012), may not follow the springboard pathway. While large EMNEs continue to grow rapidly, many small- and medium-sized EMNEs who lack the scale and scope advantages of the larger firms struggle to establish competitive footholds in target countries. The latter can be more evolutionary in their internationalization process than the former. One can posit too that EMNEs from China and India are likely to be more ambidextrous, adaptable, and amalgamable than those from Russia and Brazil. Thus far, most research has looked at SMNEs through the lens of M&As, while little attention has been paid to other important investment modes such as equity participation, co-development, greenfield investments, cross-licensing, co-production, co-marketing, co-branding, and divestments. Springboard is not a one-step act. Changing patterns, processes, and rationality in such areas as entry mode, ownership level, partnerships, leadership, market development, subsidiary roles, and intra-MNE orchestration are understudied. Dynamism associated with springboard strategies thus warrants heightened attention. These issues motivate us to consider a typology or taxonomic approach that can provide more insights into the plurality and diversity of SMNEs. Scholars can unpack each quadrant or group within the matrix they study and then identify a peculiar set of strategic or organizational traits for different types and identities of such companies. Equally, a comparative approach that contrasts EMNEs with AMNEs, compares different SMNEs from different economies or industries, and even compares MNEs who heavily springboard with those who do not will be valuable to advance our understanding of these firms. Springboard is an important means to achieve strategic gains. These gains, however, mandate considerable orchestration in both design and execution. Current research lacks specificity in the orchestration process during and after the springboard act unfolds. While most SMNEs view their home base as the lynchpin of success for their Journal of International Business Studies A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 148 global operations, more attention should be paid to the integration of operationally and geographically dispersed activities within the firm and with other players in the global business ecosystem. Expected gains from amalgamation require an orchestration system to underpin, while ambidexterity and adaptability can nurture this system as it evolves. Future research should answer important questions such as how home–host links are established, how these links differ from those in established AMNEs, what effective mechanisms are employed by which SMNEs orchestrate global operations, how strategic assets they acquired are integrated into home base operations, and how upgraded capabilities are subsequently leveraged and deployed to further spur their internationalization? Established AMNEs can offer SMNEs, particularly those from emerging economies, tremendous lessons regarding crossborder orchestration given the former’s long experience in this area but the latter should be vigilant in finding their own effective, even creative, ways in connecting, recombining, and reconfiguring key resources throughout the organization. Following this logic, research should explore how SMNEs use their home base as a reservoir to absorb and assimilate global resources, a testing ground for business models and new products, and a launchpoint for their global reach of products. The upward spiral concept we introduced remains an important area for further exploration. Digital globalization reduces the minimal scale needed to go global, enabling small businesses and entrepreneurs, especially those using digital or online platforms, to leapfrog. This influences MNE behavior in many ways, and nurtures springboard strategically and organizationally. Digital platforms (e.g., global e-commerce marketplaces, social media platforms, specialized service platforms) provide these small and new players with ‘‘plug-and-play’’ infrastructure and opportunities to put themselves in front of a vast built-in global customer base. Digital globalization thus provides a springboard for these micro-MNEs or new MNEs to reach global consumers, albeit not for the purpose of acquiring strategic assets such as technologies or brands. No MNE can be radical in everything at all times. Future research should shed insights on when SMNEs are apt to be more radical or risk-taking and when they become more gradual or risk-averse in their evolution. We submit that an SMNEs’ internationalization process would be an upward spiral trajectory, being radical and accelerated in their early-stage OFDI but their overall Journal of International Business Studies internationalization over a long horizon is still evolutionary. This has created a need for future research to decipher investment-related radical moves (path departure) and operation-related incremental moves (path dependent). MNEs act in a springboard fashion but they are still learningdriven organizations, with competence such as organizational learning, absorptive capacity, and international experience being immensely important to them (Luo & Zhang, 2016). We should not forget too that SMNEs from different countries could learn from each other. They are often competitors but also collaborators in foreign markets. Questions, such as what they can learn from the success or failure of established emerging market counterparts (e.g., those from South Korea, Singapore, and Israel) and what practices developed by these counterparts in global capability catchup can be followed, are of strong implications to both theory and practice on SMNEs. Although cultural and geographic distance are supposed to be less significant for SMNEs because of advances in global connectivity and these firms’ intent in strategic asset-seeking, the challenges encountered by these firms in bridging cultural divides between home and host country nationals and the difficulty in recruiting qualified foreign talent suggest that cultural distance still matters. Future research on human resources and crosscultural management could unpack the challenges these firms encounter in host countries both in the entry execution as well as in the context of the post-M&A phase. Comparative analysis can shed light on whether such challenges are specific to certain countries or regions or whether EMNEs in general share the same concerns, and if so, why or why not. Yildiz and Fey (2016), confirming Tung’s study (1988), have shown that psychic distance perceptions and their implications can indeed be asymmetrical in cross-border M&As where investors from AMNEs to emerging markets typically encounter less resistance vis-à-vis the other way around. Alternatively, can the challenges encountered by SMNEs in this regard be a function of the stage of internationalization, i.e., their relative newness as foreign investors? How can EMNEs win the war for talent in light of brain circulation in and weak soft power of emerging economies? This research question must look beyond the current policies of host governments (e.g., that of China and India, two of the largest diasporas in the world) to appeal to the nationalistic sentiments of members of their overseas diaspora to A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 149 return home to contribute to development at home. Research can build on the work by Tung and Lazarova (2006) on the motivation of ex-host country nationals (or returnees) to return to their countries of origin and also in the context of the changing nature of careers and the push and pull factors in global mobility (Baruch, Altman & Tung, 2016). Furthermore, how can countries build up their soft power? As noted earlier, even though China currently spends an estimated $10 billion per annum to improve its image on the world stage, its ranking has edged up only very slightly. Since the soft power index is composed of five dimensions – culture, diplomacy, education, innovation, and government – monetary investments alone may not accomplish the desired objective (McClory, 2017). Finally, given the geographic diversity of investments of SMNEs, how can they effectively manage multicultural teams (MCTs)? While there is abundant research on MCTs that involve team members who are nationals from BRICS countries (Stahl, Maznevski, Voigt & Jonsen, 2010), there is a dearth of research where the leaders of MCTs hail from an EMNE. There are both positives and negatives associated with MCTs (DiStefano & Maznevski, 2000) and the challenge for SMNEs is to harness the positives while minimizing the negatives. Future research could examine whether the dynamics in MCTs in published research apply to that in these new global players as well. The aforementioned agenda for future research is not intended to be comprehensive. Rather, it suggests that the growing presence of SMNEs and their forays into the world investment and economic community present abundant research opportunities to further understand these fascinating phenomena. The springboard view, originally developed a decade ago for EMNEs, can be extended to a greater population of multinationals that act in a springboard manner. Springboard act is a distinct form of MNE behavior, the latter being at the center of IB research over the past half a century. This article represents an ongoing attempt to better understand a greater diversity of MNE behavior in operationally interconnected yet organizationally complex and continuously evolving global competition. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors are grateful to Professor Alain Verbeke and the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. NOTES 1 The 11 journals we surveyed include 6 major IB journals (JIBS, JWB, GSJ, MIR, J. of Int’l Management, IBR) and 5 top management journals in UTD list including AMJ, ASQ, AMR, SMJ, and Org. Science. 2 Since the publication of our springboard article in 2007, the ‘‘goldilocks’’ debate took place as well (see Cuervo-Cazurra, 2012; Verbeke & Kano, 2015), which itself showcases a new interest in better understanding how EMNEs may challenge or extend existing ideas given the particularities of these countries and their firms. This debate involves whether or not EMNEs are a new phenomenon that warrants new or extended theoretical perspectives. 3 Research demonstrates that AMNEs, US and European firms included, expand abroad to source unique knowledge, for ‘‘catching up’’ with competitors (Cantwell, 1989; Kuemmerle, 1999), obtaining ‘‘technical diversity’’ (Cantwell & Janne, 1999), and springboarding to reduce their next-generation R&D costs (Chung & Yeaple, 2008). 4 The LLL framework has been criticized for missing one crucial issue: it does not explain how firms that are going abroad to learn can, at the same time, successfully compete with their teachers (see Lessard & Lucea, 2009; Ramamurti, 2009). 5 Other IB theories that can be compared with the springboard perspective if space permits include perspectives such as international new ventures (INVs), born-global firms, global latecomers and catchup, liability of emergingness, government and MNEs, as well as strategic resilience for international business. 6 For example, Cemex developed a rigorous system for managing and integrating acquisitions by relying on its strengths in standardized procedures and information technology, while Infosys designed a unique knowledge management system to serve as a boundary-spanning tool within the network promoting knowledge sharing and interaction, while also allowing private knowledge to be generated (Garud, Kumaraswamy, & Sambamurthy, 2006). Haier’s success is due not only to their expansion in developed markets and obtaining access to valuable strategic assets, but also to its home-centered capability upgrading that combines foreign technologies it acquired with its own innovation in product features and customization. 7 The resignation of two American executives, Stephen Ward and William Amelio, as Lenovo Group’s President and CEO and replacement by a Chinese CEO within a relatively short time after their much publicized acquisition of IBM PC division, highlights the Journal of International Business Studies A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 150 challenges that Chinese MNEs can encounter in retaining local talent. 8 In the 2015 ‘‘Soft power 30’’ index, China was ranked at the very bottom despite its huge spending (an estimated $10 billion per annum) to build up its soft power. In 2017, China moved up to 25th rank, respectively (McClory, 2017). For comparison, Brazil and Russia ranked 26th and 29th, respectively. India and South Africa were not ranked. REFERENCES Al-Aali, A., & Teece, D. J. 2014. International entrepreneurship and the theory of the international firm: A capability perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(1): 95–116. Bae, K., Purda, L., Welker, M., & Zhong, L. 2013. Credit rating initiation and accounting quality for emerging-market firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(3): 216–234. Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. 1989. Managing Across Borders. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Baruch, Y., Altman, Y., & Tung, R. L. 2016. Career mobility in a global era: Advances in managing expatriation and repatriation. Academy of Management Annals, 10(1): 841–889. Beebe, A. 2006. Trends and lessons learned from cross-border M&A by Chinese companies. Beijing, China: Special Report by IBM Institute for Business Value. Boisot, M., & Meyer, M. W. 2008. Which way through the open door? Reflections on the internationalization of Chinese firms. Management and Organization Review, 4(3): 349–365. Bonaglia, F., Goldstein, A., & Mathews, J. A. 2007. Accelerated internationalization by emerging markets’ multinationals: The case of the white goods sector. Journal of World Business, 42(4): 369–383. Brouthers, K. D., Nakos, G., & Dimitratos, P. 2015. SME entrepreneurial orientation, international performance and the moderating role of strategic alliance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(5): 1161–1187. Buckley, P. J., Munjal, S., Enderwick, P., & Forsans, N. 2016. The role of experiential and non-experiential knowledge in crossborder acquisitions: The case of Indian multinational enterprises. Journal of World Business, 51(5): 675–685. Cantwell, J. 1989. Technological Innovation and Multinational Corporations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Cantwell, J., & Janne, O. 1999. Technological globalization and innovative centers: The role of corporate technological leadership and locational hierarchy. Research Policy, 28(2–3): 119–144. Chaisse, J. 2017. China’s Three Prong Investment Strategy: Bilateral, Regional and Global Tracks. London, UK: Cambridge University Press. Chung, W., & Yeaple, S. 2008. International knowledge sourcing: Evidence from US firms expanding abroad. Strategic Management Journal, 29(11): 1207–1224. Cole, R. E., & Deskins, D. R. 1988. Racial factors in site location and employment patterns of Japanese auto firms in America. California Management Review, 31(1): 9–22. Cuervo-Cazurra, A. 2012. Extending theory by analyzing developing country multinational companies: Solving the Goldilocks debate. Global Strategy Journal, 2(3): 153–167. Cuervo-Cazurra, A., & Genc, M. 2008. Transforming disadvantages into advantages: Developing-country MNEs in the least developed countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(6): 957–979. Cui, L., Meyer, K. E., & Hu, H. 2014. What drives firms’ intent to seek strategic assets by foreign direct investment? A study of emerging economy firms. Journal of World Business, 49(4): 488–501. De Beule, F., Elia, S., & Piscitello, L. 2014. Entry and access to competencies abroad: Emerging market firms versus advanced market firms. Journal of International Management, 20(2): 137–152. Deng, P. 2009. Why do Chinese firms tend to acquire strategic assets in international expansion? Journal of World Business, 44(1): 74–84. Journal of International Business Studies DiStefano, J. J., & Maznevski, M. L. 2000. Creating value with diverse teams in global management. Organizational Dynamics, 29: 45–63. Dunning, J. H. 1981. International production and the multinational enterprises. London: Allen & Unwin. Dunning, J. H. 1988. The eclectic paradigm of international production: A restatement and some possible extensions. Journal of International Business Studies, 19: 1–13. Dunning, J. H., Kim, C., & Park, D. 2008. Old wine in new bottles: A comparison of emerging market TNCs today and developed country TNCs thirty years ago. In K. P. Sauvant (Ed.), The rise of transnational corporations from emerging markets: Threat or opportunity? Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. Elango, B., & Pattnaik, C. 2007. Building capabilities for international operations through networks: A study of Indian firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4): 541–555. Evans, J. S. 1991. Strategic flexibility for high technology maneuvers: A conceptual framework. Journal of Management Studies, 28(1): 69–89. Fang, T., Tung, R. L., Nematshahi, N., & Berg, L. 2017. Parachuting internationalization: A study of four Scandinavian firms entering China. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 24: 3. (forthcoming). Farrell, D., & Grant, A. 2005. Addressing China’s looming talent shortage. London: McKinsey Global Institute. Forbes. 2016. China hits record high M&A investment in Western firms. September 10, 2016. Gaffney, N., Karst, R., & Clampit, J. 2016. Emerging market MNE cross-border acquisition equity participation: The role of economic and knowledge distance. International Business Review, 25(1): 267–275. Garud, R., Kumaraswamy, A., & Sambamurthy, V. 2006. Emergent by design: Performance and transformation at Infosys technologies. Organization Science, 17(2): 277–286. Gaur, A. S., Kumar, V., & Singh, D. 2014. Institutions, resources, and internationalization of emerging economy firms. Journal of World Business, 49(1): 12–20. Gibson, C., & Birkinshaw, J. 2004. The antecedents, consequences, and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Academy of Management Journal, 47(2): 209–226. Govindarajan, V., & Ramamurti, R. 2011. Reverse innovation, emerging markets, and global strategy. Global Strategy Journal, 1(3–4): 191–205. Grewal, R., & Tansuhaj, P. 2001. Building organizational capabilities for managing economic crisis: The role of market orientation and strategic flexibility. Journal of Marketing, 65(2): 67–80. Gubbi, S., & Elango, B. 2016. Resource deepening vs. resource extension: Impact on asset-seeking acquisition performance. Management International Review, 56(3): 353–384. Gubbi, S., Aulakh, P., Ray, S., Sarkar, M. B., & Chittoor, R. 2010. Do international acquisitions by emerging-economy firms create shareholder value? The case of Indian firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(3): 397–418. Guillén, M. F., & Garcı́a-Canal, E. 2009. The American model of the multinational firm and the ‘‘new’’ multinationals from emerging economies. Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(2): 23–35. Hennart, J. M. A. 2012. Emerging market multinationals and the theory of the multinational enterprise. Global Strategy Journal, 2(3): 168–187. A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 151 Holburn, G. L., & Zelner, B. A. 2010. Political capabilities, policy risk and international investment strategy: Evidence from the global electric power generation industry. Strategic Management Journal, 31(12): 1290–1315. Hoskisson, R. E., Wright, M., Filatotchev, I., & Peng, M. W. 2013. Emerging multinationals from mid-range economies: The influence of institutions and factor markets. Journal of Management Studies, 50(7): 1295–1321. Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. 1977. The internationalization process of the firm: A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitment. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1): 23–32. Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. 2009. The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(9): 1411–1431. Kano, L. 2017. Governance of global value chains: A relational perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, forthcoming. Kedia, B., Gaffney, N., & Clampit, J. 2012. EMNEs and knowledge seeking FDI. Management International Review, 52(2): 155–173. Kogut, B., & Kulatilaka, N. 1994. Operating flexibility, global manufacturing, and the option value of a multinational network. Management Science, 40(1): 123–139. Kogut, B., & Zander, U. 1992. Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology’. Organization Science, 3(2): 383–397. Kotabe, M., Jiang, C. X., & Murray, J. Y. 2011. Managerial ties, knowledge acquisition, realized absorptive capacity and new product market performance of emerging multinational companies: A case of China. Journal of World Business, 46(2): 166–176. Kotabe, M., & Kothari, T. 2016. Emerging market multinational companies’ evolutionary paths to building a competitive advantage from emerging markets to developed countries. Journal of World Business, 51(5): 729–743. Kothari, T., Kotabe, M., & Murphy, P. 2013. Rules of the game for emerging market multinational companies from China and India. Journal of International Management, 19(3): 276–299. Kuemmerle, W. 1999. Foreign direct investment in industrial research in the pharmaceutical and electronics industries: Results from a survey of multinational firms. Research Policy, 28(2–3): 179–193. Lessard, D., & Lucea, R. 2009. Mexican multinationals: insights from CEMEX. In R. Ramamurti & J. Singh (Eds.), Emerging multinationals in emerging markets (pp. 280–311. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Leung, K., & Morris, M. W. 2015. Values, schemas, and norms in the culture–behavior nexus: A situated dynamics framework. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(9): 1028–1050. Li, P. P. 2010. Toward a learning-based view of internationalization: The accelerated trajectories of cross-border learning for latecomers. Journal of International Management, 16(1): 43–59. Li, J., Li, Y., & Shapiro, D. 2012. Knowledge seeking and outward FDI of emerging market firms: The moderating effect of inward FDI. Global Strategy Journal, 2(4): 277–295. Luo, Y., & Child, J. 2015. A composition-based view of firm growth. Management and Organization Review, 11(3): 379–411. Luo, Y., & Rui, H. 2009. An ambidexterity perspective toward multinational enterprises from emerging economies. Academy of Management Perspective, 23(4): 49–70. Luo, Y., & Tung, R. L. 2007. International expansion of emerging market enterprises: A springboard perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4): 481–498. Luo, Y., & Zhang, H. 2016. Emerging market MNEs: Qualitative review and theoretical directions. Journal of International Management, 22(4): 333–350. Madhok, A., & Keyhani, M. 2012. Acquisitions as entrepreneurship: Asymmetries, opportunities and the internationalization of multinationals from emerging economies. Global Strategy Journal, 2(1): 26–40. Mathews, J. A. 2002. Dragon multinationals: A new model for global growth. New York: Oxford University Press. Mathews, J. A. 2006. Dragon multinationals: New players in 21st century globalization. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23(1): 5–27. McClory, J. 2017. The soft power 30: A global ranking of soft power. http://Portland-communications.com. Narula, R. 2012. Do we need different frameworks to explain infant MNEs from developing countries? Global Strategy Journal, 2(3): 188–204. Narula, R., & Verbeke, A. 2015. Making internalization theory good for practice: The essence of Alan Rugman’s contribution to international business. Journal of World Business, 50(4): 612–622. Nye, J. S. 1990. Soft power. Foreign Policy, 80: 153–171. Peng, M. W. 2012. The global strategy of emerging multinationals from China. Global Strategy Journal, 2: 97–107. Ramamurti, R. 2009. What have we learned about emerging market MNEs? In R. Ramamuti & J. Singh (Eds.), Emerging multinationals in emerging markets (pp. 399–426). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Ramamurti, R. 2012. What is really different about emerging market multinationals? Global Strategy Journal, 2: 41–47. Rugman, A. 2009. Theoretical aspects of MNEs from emerging markets. In R. Ramamuti & J. Singh (Eds.), Emerging multinationals in emerging markets (pp. 42–63). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Rui, H., & Yip, G. S. 2008. Foreign acquisitions by Chinese firms: A strategic intent perspective. Journal of World Business, 43(2): 213–226. Satta, G., Parola, F., & Persico, L. 2014. Temporal and spatial constructs in service firms’ internationalization patterns: The determinants of the accelerated growth of emerging MNEs. Journal of International Management, 20(4): 421–435. Saxenian, A. 2002. Brain circulation: How high-skill immigration makes everyone better off. The Brookings Review, 20(1): 28–31. Solomon, S. 2017. In trade with Africa, US playing catch-up. http://www.voanews.com/a/trade-africa-us-playing-catchup/ 3676351.html. Stahl, G. K., Maznevski, M. L., Voigt, A., & Jonsen, K. 2010. Unraveling the effects of cultural diversity in teams: A metaanalysis of research on multicultural work groups. Journal of International Business Studies, 41: 690–709. Sun, S. L., Peng, M. W., Ren, B., & Yan, D. 2012. A comparative ownership advantage framework for cross-border M&As: The rise of Chinese and Indian MNEs. Journal of World Business, 47: 4–16. Teece, D. J. 2014. A dynamic capabilities-based entrepreneurial theory of the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(1): 8–37. Tung, R. L. 1988. The new expatriates: Managing human resources abroad. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishers. Tung, R. L. 2007. The human resource challenge to outward foreign direct investment aspirations from emerging economies: The case of China. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(5): 868–889. Tung, R. L. 2014. Human resource management in Asia. In H. Hasegawa & C. Noronha (Eds.), Asian Business and Management (2nd ed., pp. 75–96). London: Palgrave Macmillan. Tung, R. L. 2016. New perspectives on human resource management in a global context. Journal of World Business, 51(1): 142–152. Tung, R. L., & Lazarova, M. B. 2006. Brain drain versus brain gain: An exploratory study of ex-host country nationals in Central and East Europe. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(11): 1853–1872. UNCTAD. 2016. World Investment Report 2016: Investor Nationality: Policy Challenges. Geneva: United Nations. Journal of International Business Studies A general theory of springboard MNEs Yadong Luo and Rosalie L Tung 152 UNCTAD. 2017. World Investment Report 2017: Investment and the Digital Economy. Geneva: United Nations. Verbeke, A., & Kano, L. 2015. The new internalization theory and multinational enterprises from emerging economies: A business history perspective. Business History Review, 89(3): 415–445. Wang, C., Hong, J., Kafouros, M., & Wright, M. 2012. Exploring the role of government involvement in outward FDI from emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(7): 655–676. Wang, S., Luo, Y., Lu, X., Sun, J., & Maksimov, V. 2014. Autonomy delegation to foreign subsidiaries: An enabling mechanism for emerging market multinationals. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(2): 111–130. Wells, L. T. 1983. Third world multinationals: The rise of foreign direct investment from developing countries. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. World HR Lab Survey. 2004. http://www.people.com.cn/GB/ jiaoyu/22224/2366926.html. Accessed June 2, 2004. Witt, M. A., & Lewin, A. Y. 2007. Outward foreign direct investment as escape response to home country institutional constraints. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4): 579–594. Xia, J., Ma, X., Lu, J. W., & Yiu, D. W. 2014. Outward foreign direct investment by emerging market firms: A resource dependence logic. Strategic Management Journal, 35(9): 1343–1363. Yamakawa, Y., Peng, M. W., & Deeds, D. L. 2008. What drives new ventures to internationalize from emerging to developed economies? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(1): 59–82. Yildiz, H. E., & Fey, C. F. 2016. Are the extent and effect of psychic distance perceptions symmetrical in cross-border M&As? Evidence from a two-country study. Journal of International Business Studies, 47: 830–867. Yiu, D. W., Lau, C., & Bruton, G. D. 2007. International venturing by emerging economy firms: The effects of firm capabilities, home country networks, and corporate entrepreneurship. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4): 519–540. Young, S., Huang, C. H., & McDermott, M. 1996. Internationalization and competitive catch-up processes: Case study evidence on Chinese multinational enterprises. Management International Review, 36(4): 295–314. Zhou, L., Barnes, B. R., & Lu, Y. 2010. Entrepreneurial proclivity, capability upgrading and performance advantage of newness among international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(5): 882–905. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Yadong Luo is the Emery M. Findley Distinguished Chair and Professor of Management at University of Miami. His research interests include global corporate strategy, global competition and cooperation, and business and management in emerging economies, among others. Rosalie L Tung is a chaired Professor of International Business at Simon Fraser University. She is a past President of the Academy of Management and the Academy of International Business, and an elected Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, the Academy of Management, and the Academy of International Business. She has published extensively on the subject of international management. Accepted by Alain Verbeke, Editor-in-Chief, 1 September 2017. This article has been with the authors for two revisions and was single-blind reviewed. Journal of International Business Studies View publication stats