Maximise Your Exam Success with BPP Learning Media’s

Platinum Approved Materials

LEARN

Our Study Texts are the only Texts that have been reviewed by the examiner. This ensures that our coverage of the

syllabus is appropriate for your exam. By choosing our Platinum Approved Study Text you are one step nearer to

achieving the exam success you deserve.

PRACTISE AND APPLY

Our Practice & Revision Kits are the only Kits that have been reviewed by the examiner. Use our Kits and our i-Pass

CD-ROMs to reinforce and apply your knowledge. Kits are packed with past ACCA exam questions together with

full solutions and handy tutor’s hints.

i-Pass contains approximately 300 questions, covering all important syllabus areas.

REVISE AND RETAIN

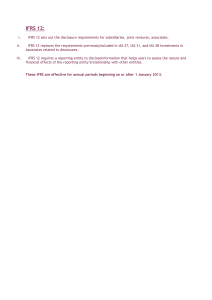

Revise using our pocket-sized Passcards and then listen to our audio Success CD to give your revision a boost.

Our Interactive Passcards product takes the Passcards, adds additional tutorials, comments and lots of testing and links

them to the Study Text. The result is a truly interactive revision experience. Revise using the on-screen Passcards and

dip into the on-screen Study Text for more detail.

BPP LEARNING MEDIA CUSTOMER SERVICES

Tel: 0845 075 1100 (UK)

Email:

learningmedia@bpp.com

Tel: +44 (0)20 8740 2211 (Overseas)

Website: www.bpp.com/learningmedia

To help maximise your chances of passing, we’ve put together

some exclusive additional ACCA resources. To access the BPP

ACCA online additional resources for this material please go to:

http://accaresources.bpp.com/student

n Create a user account if you don’t already have one.

Make sure you reply to the confirmation email.

n Log in using your registered username and password.

Select the paper you wish to access.

n Enter the code below when prompted. You will only have

to do this once for each paper you are studying.

S

T

U

D

Y

PAPER P2

CORPORATE REPORTING

(INTERNATIONAL AND

UNITED KINGDOM)

BPP Learning Media is the sole ACCA Platinum Approved Learning Partner – content

for the ACCA qualification. In this, the only Paper P2 study text to be reviewed by the

examiner:

We discuss the best strategies for studying for ACCA exams

We highlight the most important elements in the syllabus and the key skills you will need

We signpost how each chapter links to the syllabus and the study guide

We provide lots of exam focus points demonstrating what the examiner will want you to do

We emphasise key points in regular fast forward summaries

We test your knowledge of what you've studied in quick quizzes

We examine your understanding in our exam question bank

We reference all the important topics in our full index

BPP's Practice & Revision Kit, i-Pass and Interactive Passcard products also

supports this paper.

FOR EXAMS UP TO JUNE 2014

T

E

X

T

First edition 2007

Sixth edition October 2012

ISBN 9781 4453 9654 5

(Previous ISBN 9781 4453 7768 1)

e-ISBN 9781 4453 9214 1

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in

any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior

written permission of BPP Learning Media Ltd.

We are grateful to the Association of Chartered Certified

Accountants for permission to reproduce past

examination questions. The suggested solutions in the

exam answer bank have been prepared by BPP Learning

Media Ltd, unless otherwise stated.

Published by

BPP Learning Media Ltd

BPP House, Aldine Place

142-144 Uxbridge Road

London W12 8AA

www.bpp.com/learningmedia

Printed in the United Kingdom by

Polestar Wheatons

Hennock Road

Marsh Barton

Exeter

EX2 8RP

Your learning materials, published by BPP Learning

Media Ltd, are printed on paper sourced from

traceable, sustainable sources.

©

BPP Learning Media Ltd

2012

ii

Contents

Page

Introduction

Helping you to pass – the ONLY P2 Study Text reviewed by the examiner!

Studying P2

Important note for UK students

The exam paper

v

vii

vii

xxxiv

Part A Regulatory and ethical framework

1

2

3

Financial reporting framework

Professional and ethical duty of the accountant

Environmental and social reporting

3

25

55

Part B Accounting standards

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Non-current assets

Employee benefits

Income taxes

Financial instruments

Share-based payment

Provisions, contingencies and events after the reporting period

Related parties

Leases

81

125

149

175

227

241

255

263

Part C Group financial statements

12

13

14

15

16

17

Revision of basic groups

Complex groups and joint arrangements

Changes in group structures

Continuing and discontinued interests

Foreign currency transactions and entities

Group statements of cash flows

283

327

353

385

393

413

Part D Performance reporting

18

19

20

21

Performance reporting

Current developments

Reporting for specialised entities

Reporting for small and medium-sized entities

Exam question and answer bank

Mathematical tables

Index

Review form

437

495

511

529

539

627

631

Contents

iii

A note about copyright

Dear Customer

What does the little © mean and why does it matter?

Your market-leading BPP books, course materials and e-learning materials do not write and update

themselves. People write them: on their own behalf or as employees of an organisation that invests in this

activity. Copyright law protects their livelihoods. It does so by creating rights over the use of the content.

Breach of copyright is a form of theft – as well as being a criminal offence in some jurisdictions, it is

potentially a serious breach of professional ethics.

With current technology, things might seem a bit hazy but, basically, without the express permission of

BPP Learning Media:

Photocopying our materials is a breach of copyright

Scanning, ripcasting or conversion of our digital materials into different file formats, uploading

them to facebook or emailing them to your friends is a breach of copyright

You can, of course, sell your books, in the form in which you have bought them – once you have finished

with them. (Is this fair to your fellow students? We update for a reason.) Please note the e-products are

sold on a single user licence basis: we do not supply ‘unlock’ codes to people who have bought them

second-hand.

And what about outside the UK? BPP Learning Media strives to make our materials available at prices

students can afford by local printing arrangements, pricing policies and partnerships which are clearly

listed on our website. A tiny minority ignore this and indulge in criminal activity by illegally photocopying

our material or supporting organisations that do. If they act illegally and unethically in one area, can you

really trust them?

iv

Helping you to pass – the ONLY P2 Study Text reviewed

by the examiner!

BPP Learning Media – the sole Platinum

Approved Learning Partner - content

As ACCA’s sole Platinum Approved Learning Partner – content, BPP Learning Media gives you the

unique opportunity to use examiner-reviewed study materials for the 2013 and June 2014 exams. By

incorporating the examiner’s comments and suggestions regarding the depth and breadth of syllabus

coverage, the BPP Learning Media Study Text provides excellent, ACCA-approved support for your

studies.

The PER alert

Before you can qualify as an ACCA member, you do not only have to pass all your exams but also fulfil a

three year practical experience requirement (PER). To help you to recognise areas of the syllabus that

you might be able to apply in the workplace to achieve different performance objectives, we have

introduced the ‘PER alert’ feature. You will find this feature throughout the Study Text to remind you that

what you are learning to pass your ACCA exams is equally useful to the fulfilment of the PER

requirement.

Your achievement of the PER should now be recorded in your on-line My Experience record.

Tackling studying

Studying can be a daunting prospect, particularly when you have lots of other commitments. The

different features of the text, the purposes of which are explained fully on the Chapter features page, will

help you whilst studying and improve your chances of exam success.

Developing exam awareness

Our Texts are completely focused on helping you pass your exam.

Our advice on Studying P2 outlines the content of the paper, the necessary skills the examiner expects

you to demonstrate and any brought forward knowledge you are expected to have.

Exam focus points are included within the chapters to highlight when and how specific topics were

examined, or how they might be examined in the future.

Using the Syllabus and Study Guide

You can find the syllabus and Study Guide on page ix to xxxiii of this Study Text.

Testing what you can do

Testing yourself helps you develop the skills you need to pass the exam and also confirms that you can

recall what you have learnt.

We include Questions – lots of them – both within chapters and in the Exam Question Bank, as well as

Quick Quizzes at the end of each chapter to test your knowledge of the chapter content.

Introduction

v

Chapter features

Each chapter contains a number of helpful features to guide you through each topic.

Topic list

Topic list

Syllabus reference

What you will be studying in this chapter and the relevant

section numbers, together the ACCA syllabus references.

Introduction

Puts the chapter content in the context of the syllabus as

a whole.

Study Guide

Links the chapter content with ACCA guidance.

Exam Guide

Highlights how examinable the chapter content is likely to

be and the ways in which it could be examined.

Knowledge brought forward from earlier studies

What you are assumed to know from previous

studies/exams.

FAST FORWARD

Summarises the content of main chapter headings,

allowing you to preview and review each section easily.

Examples

Demonstrate how to apply key knowledge and

techniques.

Key terms

Definitions of important concepts that can often earn you

easy marks in exams.

Exam focus points

When and how specific topics were examined, or how

they may be examined in the future.

Formula to learn

Formulae that are not given in the exam but which have to

be learnt.

Gives you a useful indication of syllabus areas that

closely relate to performance objectives in your Practical

Experience Requirement (PER).

vi

Introduction

Question

Gives you essential practice of techniques covered in the

chapter.

Case Study

Real world examples of theories and techniques.

Chapter Roundup

A full list of the Fast Forwards included in the chapter,

providing an easy source of review.

Quick Quiz

A quick test of your knowledge of the main topics in the

chapter.

Exam Question Bank

Found at the back of the Study Text with more

comprehensive chapter questions. Cross referenced for

easy navigation.

Studying P2

Paper P2 Corporate Reporting is a tough paper, reflecting the demands that will be made upon the

professional accountant in his or her working life. At the Fundamentals level, you will have studied the

essentials of financial statement preparation and analysis, including those of group accounts. At the

Professional level, these essentials will be assumed knowledge. You will be required to apply them,

assuming the role of a professional adviser and analyst to the management as well as the shareholders

and other stakeholders.

What is the paper about?

The P2 syllabus comprises eight main areas:

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

The professional and ethical duty of the accountant

The financial reporting framework

Reporting the financial performance of entities

Financial statements of groups of entities

Specialised entities

Implications of changes in accounting regulation on financial reporting

The appraisal of financial performance and position of entities

Current developments

There is, of course, some overlap between these areas. For example, if you are discussing current

developments (H), you might be talking about the proposed changes to accounting for business

combinations (D) and considering the implications of changes in accounting regulation (F) and perhaps

even the ethical duty of the accountant to report those changes fairly and accurately (A).

What skills must you demonstrate?

At the Fundamentals level, the questions would be more easily categorised into syllabus areas. However,

at this level you may need to demonstrate knowledge, skills and thinking from outside the syllabus area

that the question seems to be about on the surface. The examiner has stated:

Students should be capable of relating professional issues to relevant concepts and practical

situations. The evaluation of alternative accounting practices and the identification and

prioritisation of issues will be a key element of the paper. Professional and ethical judgement will

need to be exercised, together with the integration of technical knowledge when addressing

corporate reporting issues in a business context.

So the paper is not predictable. That said, clear guidance has been given. The compulsory Section A

question, worth 50 marks, will always be on group accounts. It will also deal with issues in financial

reporting and will be case study based. In Section B, questions could be on any area of the syllabus, but

we have been told that two questions will be scenario based and one question will be an essay. You have a

choice of two from three.

Increasingly, questions are discursive rather than numerical, so it is vital that you get practice at

answering this type of question.

Important note for UK students

If you are sitting the UK P2 paper you will be studying under International standards and up to 20 marks

will be for comparisons between International and UK standards.

This Text covers all the topics you need to know under International standards and we have produced a

supplement covering the additional UK issues.

Introduction

vii

Exam technique for P2

Do not be needlessly intimidated

There is no shortcut to passing this exam. It looks very difficult indeed, and many students wonder if they

will ever pass. But many do. How do they do this?

Easy marks

All the questions are demanding, but there are many easy marks to be gained. Suppose, for example, you

had a consolidated statement of cash flows with a disposal, some foreign exchange complications and an

impairment calculation. There will be easy marks available simply for the basic cash flow aspects, setting

out the proforma, setting up your workings, presenting your work neatly. If you recognise, as you should,

that the disposal needs to be taken into account, of course you will get marks for that, even if you make a

mistake in the arithmetic. If you get the foreign exchange right, so much the better, but you could pass the

question comfortably omitting this altogether. If you’re short of time, this is what you should do.

Be ruthless in ignoring the complications

Look at the question. Within reason, if there are complications – often only worth a few marks – that you

know you will not have time or knowledge to do, cross them out. It will make you feel better. Than tackle

the bits you can do. This is how people pass a seemingly impossible paper.

Answer all questions and all parts of questions

The examiner frequently comments that students don't do this, so they miss easy opportunities to gain

marks.

Be ruthless in allocating your time

At BPP, we have seen how very intelligent students do one almost perfect question, one averagely good

and one sketchy. For a fifty mark question, the first twenty marks are the easiest to get. Then you have to

push it up to what you think is thirty to get yourself a clear pass. For a twenty-five mark question, the first

eight to ten marks are the easiest to get, and then you must try to push it up to fifteen.

Do your best question either first or second, and the compulsory question either first or second. The

compulsory question, being on groups, will always have some easy marks available for consolidation

techniques.

viii

Introduction

International

Introduction

ix

x

Introduction

Introduction

xi

xii

Introduction

Introduction

xiii

xiv

Introduction

Introduction

xv

xvi

Introduction

Introduction

xvii

xviii

Introduction

Introduction

xix

xx

Introduction

United Kingdom

Introduction

xxi

xxii

Introduction

Introduction

xxiii

xxiv

Introduction

Introduction

xxv

xxvi

Introduction

Introduction

xxvii

xxviii

Introduction

Introduction

xxix

xxx

Introduction

Introduction

xxxi

xxxii

Introduction

Introduction

xxxiii

The exam paper

The paper will comprise two sections.

Section A:

Section B:

1 compulsory case study

Choice of 2 from 3 questions (25 marks each)

Number of marks

50

50

100

Section A will be a scenario-based question which will include:

The preparation of consolidated financial statements (including consolidated statements of cash flows)

with adjustments on other syllabus areas

A written part normally covering a particular accounting treatment and ethical and social issues in

financial reporting.

Section B will normally include:

Two scenario or case study-based questions (covering a range of standards and syllabus topics, one

usually in the context of a particular industry)

A essay-style discussion question, often encompassing current developments in corporate reporting,

which may also include some short calculations.

Analysis of past papers – by sitting

June 2012

Section A

1

Consolidated statement of financial position with business combination achieved in stages and joint

operation; de-recognition of financial asset; ethics

Section B

2

3

4

Sale and leaseback, defined benefit pension plan, cash-settled share-based payment and contingent

liability in the context of a business combination

Measuring fair value, impairment of goodwill, deferred tax liabilities and the fair value option for an

accounting mismatch; shares as financial liability or equity

Changing rules on provisions (discussion and calculation)

December 2011

Section A

1

Consolidated statement of financial position with business combination achieved in stages; segment

reporting; ethics

Section B

2

3

4

xxxiv

Introduction

Internal reconstruction

Intangible assets and impairment testing rules

Revenue recognition: principles and application

June 2011

Section A

1

Groups with a foreign subsidiary, other adjustments and the remainder on ethical issues

Section B

2

3

4

Specialised industry question with IFRS 1, IFRS 3 intangible assets and restructuring plans and

provisions

Specialised industry question with reclassification of long-term debt, correction of an error, revenue

recognition, related party disclosures and classification of a employee benefit plan

Change to IFRS 9 rules for financial assets; change to expected loss model for impairment of

financial assets

December 2010

Section A

1

Consolidated statement of cash flows; ethics of changing method

Section B

2

3

4

Share-based payment; derivatives

Provisions, contingent liability, significant influence; share-based payment

Small and medium-sized entities

June 2010

Section A

1

Groups with complex group and two disposals and the remainder on ethical issues

Section B

2

3

4

A range of topics including deferred tax, impairments, a deemed disposal/discontinuation and

retirement benefits

Specialised industry with derivatives, hedge accounting, brands and the purchase of retail outlets

through companies

Flaws in lease accounting; application of Framework, sale and leaseback

December 2009

Section A

1

Consolidated statement of financial position with changes in group structure

Section B

2

3

4

Impairment: discussion and calculation

Revenue recognition; recognition of assets; joint control

Complexity in financial instruments

June 2009

Section A

1

Business combination achieved in stages; ethics

Section B

2

3

4

Financial instruments: fair value, convertible bonds, derecognition, foreign subsidiary’s debt, interest

on employee loan

Revenue recognition, assets

Employee benefits: problems of current treatments

Introduction

xxxv

December 2008

Section A

1

Group statement of cash flows with adjustments and interpretation; ethics

Section B

2

3

4

Changes to accounting for business combinations

Tangibles, intangibles and revenue recognition

Accounting standards and disclosure

June 2008

Section A

1

Groups with a foreign subsidiary, other adjustments and the remainder on ethical issues

Section B

2

3

4

Segment reporting and revenue recognition in a specialised industry

Retirement benefits and financial instruments

Transition to IFRS

December 2007

Section A

1

Piecemeal acquisition; factored receivables; environmental provision and report; ethical and social

attitudes

Section B

2

3

4

Employee benefits; provisions

Discontinued operations; deferred tax; impairment; lease

Conceptual Framework

Pilot paper

Section A

1

Statement of cash flows; criteria for consolidation; ethical behaviour

Section B

2

3

4

xxxvi

Introduction

Environmental provision; leasing; EARP; share-based payment

Deferred tax with pension scheme and financial instruments

Adoption of IFRS; proposals on business combinations

Analysis of past papers – by syllabus topic

The table below provides details of when each element of the syllabus has been examined and the

question number and section in which each element appeared. Further details can be found in the Exam

Focus Points in the relevant chapters.

Covered

in Text

chapter

Dec

2007

June

2008

Dec

2008

June

2009

Dec

2009

Q1(c)

Q1(c)

Q1(c)

Q1(c)

June

2010

Dec

2010

June

2011

Dec

2011

June

2012

Q1(b)

Q1(b)

Q1(c)

Q1(c)

3(b)

Q4

Q2(c)

Q1(a)

THE PROFESSIONAL AND ETHICAL DUTY

OF THE ACCOUNTANT

3

Professional behaviour and compliance

with accounting standards

Ethical requirements of corporate reporting

and the consequences of unethical

behaviour

Q1(c)

3

3

Social responsibility

Q1(c)

Q1(c)

Q1(c)

Q1(c)

Q3

Q1 (a)

Q2, Q3

Q1(a)

Q1(a)

Q3

Q1(a)

Q1(a),

THE FINANCIAL REPORTING FRAMEWORK

1

The contribution and limitations of financial

statements in meeting users' and capital

markets' needs

1

The applications, strengths and weaknesses

of an accounting framework

1

Q4(c)

Critical evaluation of principles and

practices

–

Revenue recognition

–

Substance over form issues

Q2(b)

Q3

Q3

REPORTING THE FINANCIAL

PERFORMANCE OF ENTITIES

18

Performance reporting

Non-current assets

4

–

Property, plant and equipment

–

Intangible assets

–

Impairment

–

Investment properties

–

Government grants

–

Borrowing costs

7

Financial instruments

11

Leases

18

Segment reporting

5

Employee benefits

6

Income taxes

Q3

Q3

Q2,Q3

Q1(a),

Q3(c)

Q1(b)

Q1(a),

Q3

3(c)

Q3

Q1(a), Q3

Q2, Q3

Q1(a)

Q2

Q1(a)

Q1(b)

Q3

Q1(a)

Q2(b)

Q1(a)

Q1(b),

Q3

Q1(a),

Q3(d)

Q1(a),

Q2

Q1,

2(a)

Q3

Q3

Q1(b),

Q3, Q4

Q1(a), Q1(a), Q2,

(b) Q3

Q3

Q4

Q1,

Q2

Q2(a)

Q2(a)

Q1(b),

Q3(b)

Q1(b)

Q1(a)

Q3(b)

Q4

Q2

Q1(a)

Q1(a)

Q2

Q1(a)

–

Provisions, contingency liabilities and

contingent assets

–

Events after the reporting period

10

Related parties

8

Share-based payment

11

Leases

Q3(d)

Q1(a),

Q2(b)

Q3

Q1(a),

Q2

Q1, 2,

3

Q3

Q1(a)

Q1(b)

Q2

Q2

Q3

Q4

Q3

Q3

Q1(a)

Q1(a)

Q3

Q2(d)

Provisions, contingencies and events after

the reporting period

9

Q1(a), Q3 Q1(a), Q3

Q4

Q3(c)

Q2, Q3

Q2

Q4

Introduction

xxxvii

Covered

in Text

chapter

Dec

2007

June

2008

Dec

2008

June

2009

Dec

2009

June

2010

Q1(b)

Q1(a)

Dec

2010

June

2011

Dec

2011

June

2012

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF GROUPS OF

ENTITIES

Q3(c)

Group accounting including statements of

cash flow

12, 13,

17

13

–

Complex groups

–

Associates

–

Joint ventures

Q1(a),

Q2

Q3

–

Group statements of cash flows

Q1(a)

Q1

Q1(a)

Q3

Q1(a)

Q1(a)

Continuing and discontinued interests

–

Discontinued operations

–

Non-current assets held for sale

Q2

Q3(a)

Q2

Changes in group structure

14

–

Mid year acquisitions

–

Disposals

–

Business combinations achieved in

stages

–

Group reorganisations

Q2

Q1(a)

Q2

Q1(a),

(b)

Q1(a),

(b)

Q 1(b)

Q1(a),

Q2

Q1(a)

Q1(a)

Q2

Foreign transactions and entities

16

–

Foreign currency transactions

–

Foreign subsidiaries

Q1(a)

Q1(b)

Q1(a)

Q1(a),

Q2

Q1(b)

Q3

Q3

Q3

Q1(a)

Q1(a),

(b)

SPECIALISED ENTITIES

20

Financial reporting in specialised, not-forprofit and public sector entities

Q2

Q3

Q3

Q2, Q3

IMPLICATIONS OF CHANGES IN

ACCOUNTING REGULATION ON

FINANCIAL REPORTING

21

The effect of changes in accounting

standards on accounting systems

12

Proposed changes to accounting standards

Q4(a)

Q2(a),

(b)

THE APPRAISAL OF FINANCIAL

PERFORMANCE AND POSITION ENTITIES

18

The creation of suitable accounting policies

18

Analysis and interpretation of financial

information and measurement of

performance

Q2(b),

Q3

Q1(b)

CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS

3, 19

Environmental and social reporting

Q1(b)

19

Convergence between national and

international reporting standards

Q4(a)

19

Comparison of national reporting

requirements

Q4(b)

Current reporting issues

1, 6, 19

xxxviii

–

Conceptual Framework

–

Fair value measurement

–

Management commentary

–

Pensions

–

Revenue recognition

Introduction

Q4

Q1(a)

Q4

Q1(a)

P

A

R

T

A

Regulatory and ethical

framework

1

2

Financial reporting

framework

Topic list

Syllabus reference

1 International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRSs)

A1

2 Corporate governance

C1

3 Conceptual framework

B2

4 Revenue recognition

A2, B1

Introduction

Welcome to the Corporate Reporting paper using International Financial

Reporting Standards (IFRS). This paper is about thinking and applying your

knowledge of the IFRS. Most of the standards and topics have been covered in

your earlier studies. However, at the Professional level, you need to think

critically about them and show an understanding of topical issues. In the exam,

you will need to put yourself in the role of an adviser to a business entity, using

your knowledge to give practical advice.

In the exam, you will often be required to consider the impact of proposed

changes to IFRS. Any such proposals are dealt with in this Study Text within

the topic to which they relate.

3

Study guide

Intellectual level

A1

Professional behaviour and compliance with accounting standards

(a)

B1

Appraise the ethical and professional issues in advising on corporate

reporting

Assess the relevance and importance of ethical and professional issues in

complying with accounting standards

Ethical requirements of corporate reporting and the consequences of

unethical behaviour

Appraise the potential ethical implications of professional and managerial

decisions in the preparation of corporate reports

The applications, strengths and weaknesses of an accounting framework

(a)

Evaluate the valuation models adopted by standard setters

C1

Performance reporting

(a)

Prepare reports relating to corporate performance for external stakeholders

B2

The applications, strength and weaknesses of an accounting framework

(a)

Evaluate the valuation models adopted by standard setters

3

(b)

Discuss the use of an accounting framework in underpinning the production

of accounting standards

3

(c)

Assess the success of such a framework in introducing rigorous and

consistent accounting standards

3

(b)

A2

(a)

3

3

3

3

Exam guide

This chapter is partly background knowledge to set the scene about the reporting framework before you

look at ethical issues. It also discusses the Management Commentary and the Conceptual Framework.

The examiner has stated that revenue recognition is important.

1 International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRSs)

One of the competences you need to fulfil Objective 10 of the Practical Experience Requirement (PER) is to

recognise and apply the external legal and professional framework and regulations to financial reporting.

You can apply the knowledge you obtain from this section of the Text to demonstrate this competence.

To date the IASB has the following standards in issue.

1.1 Current accounting standards and documents examinable at P2

The documents listed as being examinable are the latest that were issued before 30 September 2012, and

will be examinable in sittings up to June 2014. This Study Text is for exams up to and including June

2014.

[For sittings beyond June 2014, the exam year will run from 1 September to the following 31 August. The

cut off relating to examinable documents will be set 12 months prior to the start of the year. The first exam

year that will use this new cycle is the 12 months that commences 1 September 2014, in other words the

December 2014 exams onwards.]

The study guide offers more detail guidance on the depth and level at which the examinable documents

will be examined. The study guide should be read in conjunction with the examinable documents list.

4

1: Financial reporting framework Part A Regulatory and ethical framework

Title

Date issued

International Accounting Standards (IASs) / International

Financial Reporting Standards (IFRSs)

IAS 1

Presentation of financial statements

Dec 03, rev. Sept

07 and June 11

IAS 2

Inventories

Dec 03

IAS 7

Statement of cash flows

Dec 92

IAS 8

Accounting policies, changes in accounting estimates and

errors

Dec 03

IAS 10

Events after the reporting period

Dec 03

IAS 12

Income taxes

Nov 00

IAS 16

Property, plant and equipment

Dec 03

IAS 17

Leases

Dec 03

IAS 18

Revenue

Dec 93

IAS 19

Employee benefits

Nov 00, revised

2011

IAS 20

Accounting for government grants and disclosure of

government assistance

Jan 95

IAS 21

The effects of changes in foreign exchange rates

Dec 03

IAS 23

Borrowing costs

Dec 93

IAS 24

Related party disclosures

Dec 03

IAS 27

Separate financial statements

Dec 03, revised

2011

IAS 28

Investments in associates and joint ventures

Dec 03, revised

2011

IAS 32

Financial Instruments: presentation

Dec 03

IAS 33

Earnings per share

Dec 03

IAS 34

Interim financial reporting

Feb 98

IAS 36

Impairment of assets

June 98

IAS 37

Provisions, contingent liabilities and contingent assets

Sept 98

IAS 38

Intangible assets

Sept 98

IAS 39

Financial Instruments: recognition and measurement

Dec 03

IAS 40

Investment property

Dec 03

IFRS 1

First-time adoption of International Financial Reporting

Standards

June 03

IFRS 2

Share-based payment

Feb 04

IFRS 3

Business combinations

Mar 04, revised

Jan 08

IFRS 5

Non-current assets held for sale and discontinued operations

Mar 04

IFRS 7

Financial instruments: disclosures

Aug 05

IFRS 8

Operating segments

Nov 06

IFRS 9

Financial instruments

Nov 09

IFRS 10

Consolidated financial statements

May 11

Part A Regulatory and ethical framework 1: Financial reporting framework

5

Title

Date issued

IFRS 11

Joint arrangements

May 11

IFRS 12

Disclosure of interests in other entities

May 11

IFRS 13

Fair value measurement

May 11

IFRS

For Small and Medium-sized Entities

July 09

Other Statements

Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting (Chapters 1, 3 and 4)

Practice Statement: Management Commentary

EDs, Discussion Papers and Other Documents

ED

An improved conceptual framework for financial reporting. Chapter 2

ED

Financial instruments: amortised cost and impairment (including expected loss

approach)

ED

Measurement of liabilities in IAS 37

ED

Revenue from contracts with customers

ED

Leases

ED/Draft IFRS

Hedge accounting

ED

Offsetting financial assets and liabilities

ED

Improvements to IFRSs

ED

Improvements to IFRSs

ED

Investment entities

Note. The accounting of financial assets and financial liabilities is accounted for in accordance with

IFRS 9 to the extent that this standard was in issue as at 30 September 2011. For any elements

of the study guide deemed as examinable and not covered by IFRS 9, these elements should be dealt with

by studying IAS 39.

2 Corporate governance

FAST FORWARD

Corporate governance has been important in recent years and in the current syllabus it is important in the

context of ethical behaviour.

One of the major business debates recently is about corporate governance, particularly in the UK and the

USA.

Key term

Corporate governance is the system by which companies are directed and controlled.

(Cadbury Report)

The trigger for this debate was the collapse of major international companies during the 1980s, including

Maxwell, BCCI and Polly Peck. These collapses were often unexpected, and dubious (or even fraudulent)

activities were sometimes attributed to their owners and managers. These events represented a nasty

shock for countries, such as the UK and the USA, that felt they had well-regulated markets and strong

company legislation. It became obvious, however, that part of the problem was the way in which

regulation was spread between different national authorities for these global conglomerates, so that no

one national authority had the whole picture of the affairs of such companies, nor full powers over the

whole of the business.

Individual countries began to develop better guidelines for corporate governance, and efforts have been

made to produce an international standard on corporate governance.

6

1: Financial reporting framework Part A Regulatory and ethical framework

Exam focus

point

Corporate governance is covered in other papers, so is not examinable in P2. This is for background

information only.

3 Conceptual framework

FAST FORWARD

12/07

The 1989 Framework for the Preparation and Presentation of Financial Statements was replaced in 2010

by the Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting. This is the result of a joint project with the FASB.

3.1 The search for a conceptual framework

Key term

A conceptual framework, in the field we are concerned with, is a statement of generally accepted

theoretical principles which form the frame of reference for financial reporting. These theoretical principles

provide the basis for the development of new accounting standards and the evaluation of those already in

existence.

The financial reporting process is concerned with providing information that is useful in the business and

economic decision-making process. Therefore a conceptual framework will form the theoretical basis for

determining which events should be accounted for, how they should be measured and how they should be

communicated to the user.

Although it is theoretical in nature, a conceptual framework for financial reporting has highly practical final

aims.

The danger of not having a conceptual framework is demonstrated in the way some countries' standards

have developed over recent years; standards tend to be produced in a haphazard and fire-fighting

approach. Where an agreed framework exists, the standard-setting body acts as an architect or designer,

rather than a fire-fighter, building accounting rules on the foundation of sound, agreed basic principles.

The lack of a conceptual framework also means that fundamental principles are tackled more than once in

different standards, thereby producing contradictions and inconsistencies in basic concepts, such as

those of prudence and matching. This leads to ambiguity and it affects the true and fair concept of

financial reporting.

Another problem with the lack of a conceptual framework has become apparent in the USA. The large

number of highly detailed standards produced by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) has

created a financial reporting environment governed by specific rules rather than general principles. This

would be avoided if a cohesive set of principles were in place.

A conceptual framework can also bolster standard setters against political pressure from various 'lobby

groups' and interested parties. Such pressure would only prevail if it was acceptable under the conceptual

framework.

3.2 Advantages of a conceptual framework

The advantages arising from using a conceptual framework may be summarised as follows.

(a)

(b)

The situation is avoided whereby standards are being developed on a piecemeal basis, where a

particular accounting problem is recognised as having emerged, and resources were then

channelled into standardising accounting practice in that area, without regard to whether that

particular issue was necessarily the most important issue remaining at that time without

standardisation.

As stated above, the development of certain standards (particularly national standards) have been

subject to considerable political interference from interested parties. Where there is a conflict of

interest between user groups on which policies to choose, policies deriving from a conceptual

framework will be less open to criticism that the standard-setter buckled to external pressure.

Part A Regulatory and ethical framework 1: Financial reporting framework

7

(c)

Some standards may concentrate on the statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive

income (formerly statement of comprehensive income, see Chapter 18 for the details of the change

of name) whereas some may concentrate on the valuation of net assets (statement of financial

position).

3.3 Counter-argument

A counter-argument might be as follows.

(a)

(b)

(c)

Financial statements are intended for a variety of users, and it is not certain that a single conceptual

framework can be devised which will suit all users.

Given the diversity of user requirements, there may be a need for a variety of accounting standards,

each produced for a different purpose (and with different concepts as a basis).

It is not clear that a conceptual framework makes the task of preparing and then implementing

standards any easier than without a framework.

Before we look at the IASB's attempt to produce a conceptual framework, we need to consider another

term of importance to this debate: generally accepted accounting practice; or GAAP.

3.4 Generally Accepted Accounting Practice (GAAP)

This term has sprung up in recent years and its signifies all the rules, from whatever source, which govern

accounting. In individual countries this is seen primarily as a combination of:

National corporate law

National accounting standards

Local stock exchange requirements

Although those sources are the basis for the GAAP of individual countries, the concept also includes the

effects of non-mandatory sources such as:

International financial reporting standards

Statutory requirements in other countries

In many countries, like the UK, GAAP does not have any statutory or regulatory authority or definition,

unlike other countries, such as the USA. The term is mentioned rarely in legislation, and only then in fairly

limited terms.

3.5 GAAP and a conceptual framework

A conceptual framework for financial reporting can be defined as an attempt to codify existing GAAP in

order to reappraise current accounting standards and to produce new standards.

3.6 The IASB Conceptual Framework

The IASB Framework for the Preparation and Presentation of Financial Statements was produced in 1989

and is gradually being replaced by the new Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting. This is the

result of an IASB/FASB joint project and is being carried out in phases. The first phase, comprising

Chapters 1 and 3, was published in September 2010. Chapter 2 entitled ‘The reporting entity’ has not yet

been published. The current version of the Conceptual Framework includes the remaining chapters of the

1989 Framework as Chapter 4.

The Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting is currently as follows:

Chapter 1: The objective of general purpose financial reporting

Chapter 2: The reporting entity (to be issued)

Chapter 3: Qualitative characteristics of useful financial information

Chapter 4: Remaining text of the 1989 Framework:

8

1: Financial reporting framework Part A Regulatory and ethical framework

Underlying assumption

The elements of financial statements

Recognition of the elements of financial statements

Measurement of the elements of financial statements

Concepts of capital and capital maintenance

You have studied the 1989 Framework in your earlier studies. We will now look at some of these sections

in more detail.

3.7 Introduction to the Conceptual Framework

The Introduction provides a list of the purposes of the Conceptual Framework:

(a)

To assist the Board in the development of future IFRSs and in its review of existing IFRSs.

(b)

To assist the Board in promoting harmonisation of regulations, accounting standards and

procedures relating to the presentation of financial statements by providing a basis for reducing the

number of alternative accounting treatments permitted by IFRSs.

(c)

To assist national standard-setting bodies in developing national standards.

(d)

To assist preparers of financial statements in applying IFRSs and in dealing with topics that have

yet to form the subject of an IFRS.

(e)

To assist auditors in forming an opinion as to whether financial statements comply with IFRSs.

(f)

To assist users of financial statements in interpreting the information contained in financial

statements prepared in compliance with IFRSs.

(g)

To provide those who are interested in the work of the IASB with information about its approach to

the formulation of IFRSs.

The Conceptual Framework is not an IFRS and so does not overrule any individual IFRS. In the (rare) case

of conflict between an IFRS and the Conceptual Framework, the IFRS will prevail.

3.8 Chapter 1: The Objective of General Purpose Financial Reporting

The Conceptual Framework states that;

‘The objective of general purpose financial reporting is to provide information about the reporting entity

that is useful to existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors in making decisions about

providing resources to the entity.’

These users need information about:

the economic resources of the entity;

the claims against the entity; and

changes in the entity’s economic resources and claims

Information about the entity’s economic resources and the claims against it helps users to assess the

entity’s liquidity and solvency and its likely needs for additional financing.

Information about a reporting entity’s financial performance (the changes in its economic resources and

claims) helps users to understand the return that the entity has produced on its economic resources.

This is an indicator of how efficiently and effectively management has used the resources of the entity and

is helpful in predicting future returns.

The Conceptual Framework makes it clear that this information should be prepared on an accruals basis.

Information about a reporting entity’s cash flows during a period also helps users assess the entity’s

ability to generate future net cash inflows and gives users a better understanding of its operations.

3.9 Chapter 3: Qualitative characteristics of useful financial information

Qualitative characteristics are attributes that make financial information useful to users.

Part A Regulatory and ethical framework 1: Financial reporting framework

9

Chapter 3 distinguishes between fundamental and enhancing qualitative characteristics, for analysis

purposes. Fundamental qualitative characteristics distinguish useful financial reporting information from

information that is not useful or misleading. Enhancing qualitative characteristics distinguish more useful

information from less useful information.

The two fundamental qualitative characteristics are:

(a)

Relevance: relevant information has predictive value or confirmatory value, or both. It is capable

of making a difference in the decisions made by users.

The relevance of information is affected by its nature and its materiality.

(b)

Faithful representation: information must be complete, neutral and free from error (replacing

'reliability').

Financial reports represent economic phenomena in words and numbers. To be useful, financial

information must not only represent relevant phenomena but must faithfully represent the

phenomena that it purports to represent.

A complete depiction includes all information necessary for a user to understand the phenomenon being

depicted, including all necessary descriptions and explanations.

A neutral depiction is without bias in the selection or presentation of financial information. This means

that information must not be manipulated in any way in order to influence the decisions of users.

Free from error means there are no errors or omissions in the description of the phenomenon and no

errors made in the process by which the financial information was produced. It does not mean that no

inaccuracies can arise, particularly where estimates have to be made.

Substance over form

This is not a separate qualitative characteristic under the Conceptual Framework. The IASB says that to

do so would be redundant because it is implied in faithful representation. Faithful representation of a

transaction is only possible if it is accounted for according to its substance and economic reality.

3.9.1 Enhancing qualitative characteristics

Comparability

Comparability is the qualitative characteristic that enables users to identify and understand similarities in,

and differences among, items. Information about a reporting entity is more useful if it can be compared

with similar information about other entities and with similar information about the same entity for another

period or another date.

Consistency, although related to comparability, is not the same. It refers to the use of the same methods

for the same items (ie consistency of treatment) either from period to period within a reporting entity or in

a single period across entities.

The disclosure of accounting policies is particularly important here. Users must be able to distinguish

between different accounting policies in order to be able to make a valid comparison of similar items in the

accounts of different entities.

Comparability is not the same as uniformity. Entities should change accounting policies if those policies

become inappropriate.

Corresponding information for preceding periods should be shown to enable comparison over time.

Verifiability

Verifiability helps assure users that information faithfully represents the economic phenomena it purports

to represent. It means that different knowledgeable and independent observers could reach consensus

that a particular depiction is a faithful representation.

10

1: Financial reporting framework Part A Regulatory and ethical framework

Timeliness

Information may become less useful if there is a delay in reporting it. There is a balance between

timeliness and the provision of reliable information.

If information is reported on a timely basis when not all aspects of the transaction are known, it may not

be complete or free from error.

Conversely, if every detail of a transaction is known, it may be too late to publish the information because it has

become irrelevant. The overriding consideration is how best to satisfy the economic decision-making needs of

the users.

Understandability

Financial reports are prepared for users who have a reasonable knowledge of business and economic

activities and who review and analyse the information diligently. Some phenomena are inherently complex

and cannot be made easy to understand. Excluding information on those phenomena might make the

information easier to understand, but without it those reports would be incomplete and therefore

misleading. Therefore matters should not be left out of financial statements simply due to their difficulty as

even well-informed and diligent users may sometimes need the aid of an adviser to understand

information about complex economic phenomena.

The cost constraint on useful financial reporting

This is a pervasive constraint, not a qualitative characteristic. When information is provided, its benefits

must exceed the costs of obtaining and presenting it. This is a subjective area and there are other

difficulties: others, not the intended users, may gain a benefit; also the cost may be paid by someone other

than the users. It is therefore difficult to apply a cost-benefit analysis, but preparers and users should be

aware of the constraint.

3.9.2 Underlying assumption

The 1989 Framework identified two underlying assumptions – accruals and going concern.

The Conceptual Framework makes it clear that financial information should be prepared on an accruals

basis but only identifies one underlying assumption – going concern.

3.10 Exposure Draft: Chapter 2: The Reporting Entity

This ED was issued in March 2010. It presents the IASB's consideration of issues in the development of a

reporting entity concept for inclusion in the Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting. There are four

sections.

3.10.1 The reporting entity concept

This deals with general issues relating to the reporting entity concept. For example, it considers whether a

precise definition of a reporting entity is necessary and whether a reporting entity must be a legal entity.

The Board's conclusion at this stage is that the conceptual framework should broadly describe rather than

precisely define a reporting entity as a circumscribed area of business activity of interest to present and

potential equity investors, lenders and other creditors who cannot directly obtain the information they

need in making decisions about providing resources to the entity and in assessing whether management

and the governing board of the entity have made efficient and effective use of the resources provided.

Examples of reporting entities include a sole trader, corporation, trust, partnership, association and group.

3.10.2 When does an entity control another entity?

Consolidated financial statements are presented when control exists. Control exists where an entity has

the power to direct the activities of another entity to generate benefits or limit losses to itself.

If control is shared, no consolidated financial statements need be presented.

Part A Regulatory and ethical framework 1: Financial reporting framework

11

3.10.3 Portion of an entity

A portion of an entity could qualify as a reporting entity if the economic activities of that portion can be

distinguished objectively from the rest of the entity and financial information about that portion of the

entity has the potential to be useful in making decisions about providing resources to that portion of the

entity.

3.10.4 Financial statements other than consolidated financial statements

This section considers two issues:

(a)

Parent-only financial statements

(b)

Combined financial statements. These would include information about two or more commonly

controlled entities.

The IASB's preliminary conclusion is that (a) parent-only financial statements may be presented

provided they are included in the same financial report as consolidated financial statements and

(b) combined financial statements might provide useful information about commonly controlled entities

as a group.

3.11 Potential problems

The UK's Accounting Standards Board (ASB) has highlighted a number of potential objections that may be

made to the proposals.

(a)

Users. The ASB is concerned about the proposal that the objective of financial reporting should

focus only on decision-usefulness, with stewardship being subsumed within this rather than being

referred to as a specific part of the objective, or a separate objective. The ASB believes that

stewardship should be a separate objective. The ASB is also concerned that the shareholder user

perspective is being downplayed.

(b)

Qualitative characteristics: what happens to reliability? The DP proposes replacing the

qualitative characteristic of 'reliability' in the current Framework with 'faithful representation'.

The ASB believes that faithful representation is a softer notion which, when combined with a lack of

specific identification of substance over form as a principle, could lead to a number of problems.

(c)

Financial reporting or financial statements. The ASB believes the boundary between financial

statements and financial reporting has not been properly considered.

(d)

Limited in scope. The Discussion Paper is limited to private enterprises, rather than, as the ASB

believes it should be, encompassing the not-for profit sector.

(e)

Too theoretical. This may alienate preparers and auditors of accounts.

(f)

Too piecemeal. This is likely to lead to internal inconsistency.

(g)

The entity perspective is adopted without an in-depth comparison with other possible

perspectives (such as the proprietary perspective, the parent shareholder perspective and other

hybrid models).

(h)

The differentiation between fundamental and enhancing qualitative characteristics is artificial.

(i)

The qualitative characteristic of 'verifiability' is problematic.

(j)

In the proposed 'Reporting Entity' chapter, the entity perspective and the definitions of control

have been insufficiently thought through. In addition, the 'risks and rewards' model is not

adopted, thereby losing a useful concept.

3.12 Recent developments

So far the other parts of the Framework are still at the discussion stage. Below is a summary of progress

at the time of writing (October 2012):

12

1: Financial reporting framework Part A Regulatory and ethical framework

(a)

Objectives and qualitative characteristics – see above.

(b)

Elements and recognition. The Board has tentatively agreed that the focus of the definition of an

asset should be on a present economic resource rather than on future economic benefits and an

assessment of likelihood should be removed from the definition of an asset. The definition should

focus on the present rather than on past transactions or events. No definition of a liability has been

agreed.

(c)

Measurement. Various measurement bases have been discussed. They are divided into past

present and future. Past bases are:

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

Past entry price

Modified past entry amount

Past exit price

Present bases are:

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

(iv)

Current entry price

Current exit price

Current equilibrium price

Value in use

Future bases are:

(i)

(ii)

Exam focus

point

Future entry price

Future exit price

(d)

Reporting entity – see above

(e)

Purpose and status – discussions pending

(f)

Application to not for profit entities – discussions pending

(g)

Remaining issues – discussions pending

The examiner has flagged this topic as important. Keep an eye on future developments by reading Student

Accountant and www.iasplus.com/agenda/framework.htm

4 Revenue recognition

FAST FORWARD

6/08, 12/08, 6/11, 12/11

Revenue recognition is straightforward in most business transactions, but some situations are more

complicated.

4.1 Introduction

Accruals accounting is based on the matching of costs with the revenue they generate. It is crucially

important under this convention that we can establish the point at which revenue may be recognised so

that the correct treatment can be applied to the related costs. For example, the costs of producing an item

of finished goods should be carried as an asset in the statement of financial position until such time as it

is sold; they should then be written off as a charge to the trading account. Which of these two treatments

should be applied cannot be decided until it is clear at what moment the sale of the item takes place.

The decision has a direct impact on profit since under the prudence concept it would be unacceptable to

recognise the profit on sale until a sale had taken place in accordance with the criteria of revenue

recognition.

Revenue is generally recognised as earned at the point of sale, because at that point four criteria will

generally have been met.

Part A Regulatory and ethical framework 1: Financial reporting framework

13

The product or service has been provided to the buyer.

The buyer has recognised his liability to pay for the goods or services provided. The converse of

this is that the seller has recognised that ownership of goods has passed from himself to the

buyer.

The buyer has indicated his willingness to hand over cash or other assets in settlement of his

liability.

The monetary value of the goods or services has been established.

At earlier points in the business cycle there will not, in general, be firm evidence that the above criteria

will be met. Until work on a product is complete, there is a risk that some flaw in the manufacturing

process will necessitate its writing off; even when the product is complete there is no guarantee that it will

find a buyer.

At later points in the business cycle, for example when cash is received for the sale, the recognition of

revenue may occur in a period later than that in which the related costs were charged. Revenue

recognition would then depend on fortuitous circumstances, such as the cash flow of a company's

customers, and might fluctuate misleadingly from one period to another.

However, there are times when revenue is recognised at other times than at the completion of a sale.

For example, in the recognition of profit on long-term construction contracts. Under IAS 11 Construction

contracts contract revenue and contract costs associated with the construction contract should be

recognised as revenue and expenses respectively by reference to the stage of completion of the contract

activity at the year end.

(a)

(b)

Owing to the length of time taken to complete such contracts, to defer taking profit into account

until completion may result in the statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive income

reflecting, not so much a fair view of the activity of the company during the year, but rather the

results relating to contracts which have been completed by the year end.

Revenue in this case is recognised when production on, say, a section of the total contract is

complete, even though no sale can be made until the whole is complete.

4.2 IAS 18 Revenue

FAST FORWARD

IAS 18 Revenue is concerned with the recognition of revenues arising from fairly common transactions.

–

–

–

The sale of goods

The rendering of services

The use by others of enterprise assets yielding interest, royalties and dividends

Generally revenue is recognised when the entity has transferred to the buyer the significant risks and

rewards of ownership and when the revenue can be measured reliably.

IAS 18 governs the recognition of revenue in specific (common) types of transaction. Generally,

recognition should be when it is probable that future economic benefits will flow to the enterprise and

when these benefits can be measured reliably.

Income, as defined by the IASB's Framework document (see above), includes both revenues and gains.

Revenue is income arising in the ordinary course of an enterprise's activities and it may be called different

names, such as sales, fees, interest, dividends or royalties.

4.3 Scope

IAS 18 covers the revenue from specific types of transaction or events.

Sale of goods (manufactured products and items purchased for resale)

Rendering of services

Use by others of enterprise assets yielding interest, royalties and dividends

Interest, royalties and dividends are included as income because they arise from the use of an entity's

assets by other parties.

14

1: Financial reporting framework Part A Regulatory and ethical framework

Key terms

Interest is the charge for the use of cash or cash equivalents or amounts due to the entity.

Royalties are charges for the use of non-current assets of the entity, eg patents, computer software and

trademarks.

Dividends are distributions of profit to holders of equity investments, in proportion with their holdings, of

each relevant class of capital.

The standard specifically excludes various types of revenue arising from leases, insurance contracts,

changes in value of financial instruments or other current assets, natural increases in agricultural assets

and mineral ore extraction.

4.4 Definitions

The following definitions are given in the standard.

Key terms

Revenue is the gross inflow of economic benefits during the period arising in the course of the ordinary

activities of an enterprise when those inflows result in increases in equity, other than increases relating to

contributions from equity participants.

(IAS 18)

Fair value is the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability, in an orderly

transaction between market participants at the measurement date.

(IFRS 13)

Revenue does not include sales taxes, value added taxes or goods and service taxes which are only

collected for third parties, because these do not represent an economic benefit flowing to the entity. The

same is true for revenues collected by an agent on behalf of a principal. Revenue for the agent is only the

commission received for acting as agent.

4.5 Measurement of revenue

When a transaction takes place, the amount of revenue is usually decided by the agreement of the buyer

and seller. The revenue is actually measured, however, as the fair value of the consideration received,

which will take account of any trade discounts and volume rebates.

4.6 Identification of the transaction

Normally, each transaction can be looked at as a whole. Sometimes, however, transactions are more

complicated, and it is necessary to break a transaction down into its component parts. For example, a sale

may include the transfer of goods and the provision of future servicing, the revenue for which should be

deferred over the period the service is performed.

At the other end of the scale, seemingly separate transactions must be considered together if apart they

lose their commercial meaning. An example would be to sell an asset with an agreement to buy it back at a

later date. The second transaction cancels the first and so both must be considered together.

4.7 Sale of goods

Revenue from the sale of goods should only be recognised when all these conditions are satisfied.

(a)

The entity has transferred the significant risks and rewards of ownership of the goods to the buyer

(b)

(c)

The entity has no continuing managerial involvement to the degree usually associated with

ownership, and no longer has effective control over the goods sold

The amount of revenue can be measured reliably

(d)

It is probable that the economic benefits associated with the transaction will flow to the enterprise

(e)

The costs incurred in respect of the transaction can be measured reliably

Part A Regulatory and ethical framework 1: Financial reporting framework

15

The transfer of risks and rewards can only be decided by examining each transaction. Mainly, the transfer

occurs at the same time as either the transfer of legal title, or the passing of possession to the buyer –

this is what happens when you buy something in a shop.

If significant risks and rewards remain with the seller, then the transaction is not a sale and revenue

cannot be recognised, for example if the receipt of the revenue from a particular sale depends on the buyer

receiving revenue from his own sale of the goods.

It is possible for the seller to retain only an 'insignificant' risk of ownership and for the sale and revenue

to be recognised. The main example here is where the seller retains title only to ensure collection of what

is owed on the goods. This is a common commercial situation, and when it arises the revenue should be

recognised on the date of sale.

The probability of the enterprise receiving the revenue arising from a transaction must be assessed. It may

only become probable that the economic benefits will be received when an uncertainty is removed, for

example government permission for funds to be received from another country. Only when the uncertainty

is removed should the revenue be recognised. This is in contrast with the situation where revenue has

already been recognised but where the collectability of the cash is brought into doubt. Where recovery

has ceased to be probable, the amount should be recognised as an expense, not an adjustment of the

revenue previously recognised. These points also refer to services and interest, royalties and dividends

below.

Matching should take place, ie the revenue and expenses relating to the same transaction should be

recognised at the same time. It is usually easy to estimate expenses at the date of sale (eg warranty costs,

shipment costs, etc). Where they cannot be estimated reliably, then revenue cannot be recognised; any

consideration which has already been received is treated as a liability.

4.8 Rendering of services

When the outcome of a transaction involving the rendering of services can be estimated reliably, the

associated revenue should be recognised by reference to the stage of completion of the transaction at the

year end. The outcome of a transaction can be estimated reliably when all these conditions are satisfied.

(a)

The amount of revenue can be measured reliably

(b)

It is probable that the economic benefits associated with the transaction will flow to the enterprise

(c)

The stage of completion of the transaction at the year end can be measured reliably

(d)

The costs incurred for the transaction and the costs to complete the transaction can be measured

reliably

The parties to the transaction will normally have to agree the following before an enterprise can make

reliable estimates.

(a)

(b)

(c)

Each party's enforceable rights regarding the service to be provided and received by the parties

The consideration to be exchanged

The manner and terms of settlement

There are various methods of determining the stage of completion of a transaction, but for practical

purposes, when services are performed by an indeterminate number of acts over a period of time, revenue

should be recognised on a straight line basis over the period, unless there is evidence for the use of a

more appropriate method. If one act is of more significance than the others, then the significant act should

be carried out before revenue is recognised.

In uncertain situations, when the outcome of the transaction involving the rendering of services cannot be

estimated reliably, the standard recommends a no loss/no gain approach. Revenue is recognised only to

the extent of the expenses recognised that are recoverable.

This is particularly likely during the early stages of a transaction, but it is still probable that the enterprise

will recover the costs incurred. So the revenue recognised in such a period will be equal to the expenses

incurred, with no profit.

16

1: Financial reporting framework Part A Regulatory and ethical framework

Obviously, if the costs are not likely to be reimbursed, then they must be recognised as an expense

immediately. When the uncertainties cease to exist, revenue should be recognised as laid out in the first

paragraph of this section.

4.9 Interest, royalties and dividends

When others use the enterprise's assets yielding interest, royalties and dividends, the revenue should be

recognised on the bases set out below when:

(a)

(b)

it is probable that the economic benefits associated with the transaction will flow to the enterprise;

and

the amount of the revenue can be measured reliably.

The revenue is recognised on the following bases.

(a)

(b)

(c)

Interest is recognised on a time proportion basis that takes into account the effective yield on the

asset

Royalties are recognised on an accruals basis in accordance with the substance of the relevant

agreement

Dividends are recognised when the shareholder's right to receive payment is established

It is unlikely that you would be asked about anything as complex as this in the exam, but you should be

aware of the basic requirements of the standard. The effective yield on an asset mentioned above is the

rate of interest required to discount the stream of future cash receipts expected over the life of the asset to

equate to the initial carrying amount of the asset.

Royalties are usually recognised on the same basis that they accrue under the relevant agreement.

Sometimes the true substance of the agreement may require some other systematic and rational method

of recognition.

Once again, the points made above about probability and collectability on sale of goods also apply here.

4.10 Disclosure

The following items should be disclosed.

(a)

The accounting policies adopted for the recognition of revenue, including the methods used to

determine the stage of completion of transactions involving the rendering of services

(b)

The amount of each significant category of revenue recognised during the period including

revenue arising from:

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

(iv)

(v)

(c)

The sale of goods

The rendering of services

Interest

Royalties

Dividends

The amount of revenue arising from exchanges of goods or services included in each significant

category of revenue

Any contingent gains or losses, such as those relating to warranty costs, claims or penalties should be

treated according to IAS 37 Provisions, contingent liabilities and contingent assets (covered in your earlier

studies).

4.11 Question practice

Exam focus

point

The examiner has recently emphasised that revenue recognition is an important topic, so have a go at the

questions below.

Part A Regulatory and ethical framework 1: Financial reporting framework

17

Question

Recognition