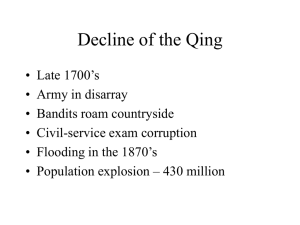

EARLY EUROPEAN INTEREST IN CHINA The first European to arrive in China was Jorge Álvares, who was a Portuguese explorer during the Age of Exploration. Álvares arrived in southern China in May of 1513. His arrival led to a wave of European merchants that travelled to China in hopes of gaining access to the many different types of goods that that country had to offer. The same was occurring in other regions of Far East Asia in the 18th century, including India and Indochina. For example, Britain famously colonized India with the economic trade of the British East India Company. As well, France had established routes to Indochina, which was partly made up of the modern nation of Vietnam. For their part, the Qing rulers wanted to limit European trading in their territory. As such, the Qing established the Canton System, which forced all foreign nations to trade only at the port of Canton. The city of Canton, which today is called Guangzhou, is a city in the south of China. The Qing restricted all foreign nations and companies to trade as this port in the hopes of limiting outside influence on Chinese society. The Canton System annoyed the European merchants, because it limited their access to other parts of the country. Regardless, the demand for Chinese goods was high in Europe, which caused the European merchants to obey the Qing restrictions. The most popular Chinese goods in Europe included tea, silk and porcelain. The demand for Chinese goods and increased trade led the European nations, especially Britain and France, to push China to end the Canton System of trade. This situation led to increasing tensions between the Qing rulers and foreign nations. At the same time, China was struggling with internal issues such as overpopulation and government corruption. As such, historians have argued that the Qing Dynasty began to lose some of its control over the nation. Regardless, the role that opium played in China came to have a significant impact on China’s trade with foreign nations and led to the First Opium War. OPIUM WARS The First Opium War was fought between the Qing Dynasty of China and Britain and took place from September 4th, 1839 until August 29th, 1842. The Qing Dynasty attempted to control outside influence in the country through the ‘Canton System’.The Qing restricted all foreign nations and companies to trade at Canton in the hopes of limiting outside influence on Chinese society. The Canton System annoyed the European merchants, because it limited their access to other parts of the country. As such, the First Opium War resulted from European frustrations against the Canton System. The First Opium War was a major victory for the British Empire in the Far East. For instance, the victory resulted in the Treaty of Nanking and gave Britain significant trading power in China. The Chinese referred to it as an ‘unequal treaty’, which is a term they gave to a series of treaties that they signed with western powers that they considered unfair or unjust. The Second Opium War was another important conflict between the Qing Dynasty of China and the British and French Empires. It that took place from October 8th, 1856 until October 24th, 1860. While the Treaty of Nanking from the First Opium War was incredibly beneficial to British interests in China, Britain wanted to gain more access to the region throughout the 1840s and 1850s. In fact, Britain demanded that opium be legalized in China, and argued for even more control over general trade within all of China. The Second Opium War ended in October of 1860 following the Convention of Peking, which saw the Qing leadership agree to terms with the British, French and Russia. In all, the Second Opium War was a humiliating loss for the Qing Dynasty and led to increased western influence in China. In fact, the major western powers of the time (Britain, France, Russia, Japan and Germany) established major spheres of influence in China that lasted throughout the end of the 19th century. As a result, the Qing loss in the Second Opium War led to increased trade by the western powers in China and resulted in growth for the overall trade of opium in China. OUTSIDE INFLUENCE IN CHINA The 19th century was a time of great change for China. At the time, the western powers were at their height in terms of the Age of Imperialism and had established large empires across the world. As such, they were also imposing their influence on China in the form of ‘spheres of influence’. In fact, the major western powers of the time (Britain, France, Russia, Japan and Germany) established major spheres of influence in China that lasted throughout the end of the 19th century. The western victories in the two Opium Wars were important factors in the expansion of these spheres of influence and the downfall of authority of the Qing government. Following its loss of the two Opium Wars, China entered a period where foreign imperial powers developed spheres of influence within its borders. Each of the following nations developed and established spheres of influence in China after the mid-1800s: France, Britain, Germany, Russia and Japan. For example, in 1860, Russia captured a large portion on Northern China and controlled it as its own ‘sphere of influence’. Japan also took advantage of China in its weakened state. For example, it worked to increase its influence in Korea, a country that China had once dominated. The two countries eventually erupted into war over control of Korea in the form of the First Sino-Japanese War, which took place from 1894 to 1895. Similar to the previous Opium Wars, the First Sino-Japanese War proved to be another crushing defeat for the Qing Dynasty and China. As a result, China was forced to give control of Korea, the island of Taiwan and the Liaodong Peninsula to Japan. As well, Japan began to establish its own sphere of influence on the eastern coast of China. For its part, the United States did not establish its own sphere of influence within China but the United States government sought to establish an ‘Open Door Policy’ in China meaning it wanted equal access to trade in China for all nations. The policy was meant to prevent foreign powers from carving up China into colonies, thus denying the United States access to lucrative trade markets.