Anti-Bullying Measures for Neurodiverse Employees: A Case Study

advertisement

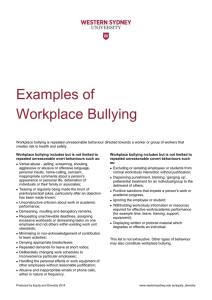

Case Taming the Raging Bully! A Case Study Critically Exploring Anti-bullying Measures to Support Neurodiverse Employees South Asian Journal of Business and Management Cases 9(1) 54–67, 2020 © 2019 Birla Institute of Management Technology Reprints and permissions: in.sagepub.com/journals-permissions-india DOI: 10.1177/2277977919881406 journals.sagepub.com/home/bmc Damian Mellifont1 Abstract Disclosure of neurodiversity in the workplace can attract unfavourable attention. The aim of this case study is to critically investigate the collective potential of specialized and generic mental health promotion guides to help prevent or treat the bullying of neurodiverse employees. Applying qualitative thematic analysis to eight of these guides originating from Australia, Canada and England, this research offers three key messages that should be of interest to policymakers and practitioners working in the Asia-Pacific region and elsewhere. First, guides as reviewed by this study collectively support antibullying themes across dimensions of policy/procedures, education, legal, leadership and monitoring/ support. Second, evidence sourced from scholarly and grey literature raise challenges that if overlooked might reduce the effectiveness of guide endorsed anti-bullying measures. Finally, this study raises the prospect that anti-bullying measures to assist mentally diverse staff might be more effective when potential synergies between these are recognized and encouraged. Keywords Attitudes, Australia, bullying, case study, neurodiversity Workplace bullying comes in many varieties (Bond, Tuckey, & Dollard, 2010). These range from covert actions, which include rumour-mongering about people with the aim of hurting their status (O’Rourke & Antioch, 2016), undertaking unfair criticisms and dismissing a person’s standpoint Disclaimer: This case is written for classroom discussion and is not intended to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation, or to represent successful or unsuccessful managerial decision-making, or endorse the views of the management. The views and opinions expressed in this case are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of South Asian Journal of Business and Management Cases. 1 Centre for Disability Research and Policy, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia. Corresponding author: Damian Mellifont, Centre for Disability Research and Policy, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia. E-mail: damian.mellifont@sydney.edu.au Mellifont 55 (Australian Human Rights Commission [AHRC], 2010), through to physical or verbal mistreatment (Bytheway, Warner, & Cotchin, 2012). Butterworth, Leach, and Kiely (2016, p. 1086) stated that bullying is ‘characterized by behaviour that harasses, offends, socially excludes or interferes with the job performance of victims.’ Other definitions highlight inappropriate behaviours, which are repeated across a time interval to achieve power advantages over others who have problems in protecting themselves (Alberta Health Services [AHS], 2014; Branch, Ramsay, & Barker, 2013; Ternan, Dollard, & LaMontagne, 2013). Hence, ‘one-off’ behaviour cannot be considered to be bullying, nor can conflicts among two individuals holding a similar level of power (Bond et al., 2010; Glambek, Skogstad, & Einarsen, 2016). Bullying can involve a multitude of minor actions that together represent methodical mistreatment (Salin, 2008). Nielsen and Knardahl (2015) describe bullying as a two-stage process with the first stage consisting of repeated bullying conduct and the second where the person feels victimized by such conduct. Devonish (2017) also recognizes perceptions of victimization as one of the broadly accepted characteristics of bullying in the workplace. Bullying tends to be seen as an interchange among a victim and an offender (Wu & Wu, 2018). Furthermore, it should be appreciated that bullying is not necessarily confined to the behaviours of a sole perpetrator. Indeed, bullying can be contagious in the sense that, ‘bullies breed new bullies’ (Paterson, 2011, p. 113). The risk being that some neurodiverse employees might find themselves the target of group bullying (i.e., ‘mobbing’) activity. Disturbingly, persons partaking in mobbing can submit to peer pressures, which are more commonly related to adolescents (Canadian Mental Health Association [CMHA], 2018). Workplace Bullying Prevalence and Consequences Bullying in the workplace represents a serious and prevalent matter (O’Rourke & Antioch, 2016). Numerous studies support this position. For example, the Lee and Brotheridge (2006, p. 365) study of 180 Canadian employees revealed, ‘we found that 72 respondents, or 40 per cent of the sample, reported that they had experienced one or more acts of bullying or aggressive behaviours at least once per week in the past 6 months.’ Moreover, a study of seven National Health Service trusts located in England found bullying to be a substantial issue (Carter et al., 2013). From the USA, a national survey conducted in 2010 reported 35 per cent of American workers directly experiencing bullying in the workplace (Boccio & Macari, 2014, p. 36 citing Workplace Bullying Institute, 2010). The Australian Workplace Barometer study described almost 7 per cent of employees experiencing bullying across a half-year timeframe (Leach, Poyser, & Butterworth, 2016, p. 1 citing Dollard et al., 2012). New Zealand research involving more than 1700 participants revealed workplace bullying experiences across the past half-year period being reported within almost 18 per cent of responses (O’Driscoll et al., 2011). Further, in noting that more than one-fifth of Finnish public-sector respondents reported having experienced task-oriented bullying on multiple occasions each month, Venettoklis and Kettunen (2016, p. 378) proceeded to suggest that public sector bullying is apparently more prevalent than that found in the private sector. This disparity is explained in terms of private sector economics encouraging managers to promptly address bullying behaviour (Venettoklis & Kettunen, 2016). Nevertheless, the broad extent of workplace bullying should be recognized. Nielsen, Matthiesen, and Einarsen (2010) and Nielsen and Knardahl (2015, p. 129) posited that globally an estimated 15 per cent of employees are objects of methodical bullying activity while 11 per cent feel that they are victims of this activity. The practical implications of workplace bullying statistics should not be understated. Bullying has significant outcomes for individuals, workplaces as well as society (Worth & Squelch, 2015). 56 South Asian Journal of Business and Management Cases 9(1) For people who closely relate to their work roles, being bullied can be shattering (Lutgen-Sandvik, 2008). Meglich-Sespico, Faley, and Knapp (2007) warn that persistent mistreatment impacts targets’ mental health. Bytheway et al. (2012, p. 17) elaborated that ‘there is a range of psychological and physical illnesses and injuries that can be caused by exposure to bullying in the workplace, including anxiety disorders, stress, depression, and insomnia.’ Referencing a Tehrani (2004) study involving health care professionals, Bond et al. (2010) reported that victims along with others who witness bullying behaviours can show symptoms suggestive of post-traumatic stress. In addition, on-going mobbing can corrode the victim’s self-esteem and confidence (CMHA, 2018), while holding other serious implications including psychological harm, unemployment and suicidal issues (Paterson, 2011). Bullying also has broad-ranging implications for organizations and their practices. In this regard, Harrington, Rayner, and Warren (2012) advise that HR practitioners might be suspicious of victims’ bullying reports against their managers. While tending to lower the work performances of those bullied, bullying can see workplaces suffering from reduced productivity, greater absence from work and low morale (Bytheway et al., 2012; Samnani & Singh, 2014). Crucially at a social level, Paterson (2011) cautioned, when citizens learn of bullying practice within the public service, society itself is worse off. Workplace Bullying and Neurodiverse Employees Triggers for workplace bullying are not thoroughly comprehended (Dhar, 2012). More specifically, individual precursors to this behaviour have been less broadly examined than organizational factors (Francioli et al. 2016 citing Glaso, Nielsen, & Einarsen, 2009). Vickers (2015) also indicates that investigations into the bullying of persons with disability are infrequent. Nevertheless, it is important to consider what is known about neurodiversity in terms of attracting bullying behaviour in the workplace. CMHA (2018) cautioned that mentally diverse persons can often be on the receiving end of bullying, mockery and rejection. According to the AHRC (2010), mental ill health can produce misinterpretation, perplexity and occasionally alarm. Following on, Broomhall (2013, p. 2) describes a survey involving American, Australian, English and Irish respondents whereby 85 per cent of individuals who disclosed their mental ill health in the workplace perceived that this disclosure held an unfavourable influence. Citing Felson (1992), Einarsen (2000) also suggests that individuals who break with social customs involving polite exchanges may readily evoke aggression from others. Further, Beecher (2003) warns that a precarious situation can become apparent where empathy deficient staff move to single out mentally unwell employees to be bullied. Staff who have invisible conditions are as likely, or potentially more likely to be mistreated than those with visible conditions (Fevre, Robinson, Lewis, & Jones, 2013, p. 303). Howard, Johnston, Wech, and Stout (2016) suggest that organizations should comprehend and comprehensively deal with workplace bullying. An important part of this understanding is to better grasp ways in which to support neurodiverse employees who might find themselves as targets for workplace bullies. Hence, when considering the particular needs of mentally diverse staff at risk of being bullied or who are presently experiencing this unethical behaviour, it is proper that HR practitioners working in the Asia-Pacific region and elsewhere have access to resources, which might assist in their ability to handle these situations. One such possible resource is that of workplace mental health promotion guides. These guides endeavour to promote mental health among mentally diverse staff members (i.e., specialized guides) or to support the mental well-being of these persons along with others throughout the workplace (i.e., generic guides). This exploratory study thus aims to critically investigate the collective potential of these guides to help prevent or treat the bullying of neurodiverse employees. Mellifont 57 Methods This research follows the Yin (2004) three-step approach to conduct case study research. These steps are as follows: a) defining the case study; b) determining whether to conduct single or multiple cases; and c) deciding whether to commence with a theoretical standpoint. The case for this study is defined as a mental health promotion guide with the potential to help prevent or treat the bullying of staff who are experiencing mental health challenges. Applying purposeful sampling, cases (i.e., guidelines) were identified by executing the Internet search term: bully* AND ‘employees with mental illness’. These search terms were designed to produce results of sufficient volume and content so as to effectively inform the study aim. Inclusion criteria were as follows: the case is publicly accessible; the case is identified as a guide promoting the mental health of neurodiverse employees or mental well-being of all staff (including those with mental ill health), the case offers measure(s) with potential to help prevent and/or treat the bullying of neurodiverse employees; and the case is unique (i.e., not repeated in search results). Deciding not to commence with a theoretical position and applying the Braun and Clarke (2006) approach to conducting the thematic analysis, themes were inductively derived from the case studies. Within this approach, the author undertook an iterative process of reading the cases (i.e., guidelines), locating themes, specifying and defining themes, reassessing themes and recording findings in an analytical table. Analysis of guideline endorsed anti-bullying themes was not undertaken unquestioningly. Enabling this critical assessment, a Google Scholar search for recently published journal articles (i.e., since 2013) using the search terms ‘bullying at work’ AND ‘targets’ AND ‘mental illness’ was applied. Relevant results were confined to journal articles meeting the inclusion criterion of supporting and/or challenging one or more of the mental health promotion guide’s informed themes. Grey literature meeting this inclusion criterion and sourced from the aforementioned Internet search query was also accepted as being relevant to this critical investigation. Results Internet search terms ‘bully’ and ‘employees with mental illness’ produced 58 results. Of these possibilities, eight cases (i.e., guidelines) were identified with five of these published in Canada, two in Australia and one in England. A total of five of these guides broadly support mental health for all staff members—including those with mental illness (AHRC, 2010; AHS, 2014; Canadian Cancer Society [CCS], 2012; CMHA, 2018; Great-West Life Centre for Mental Health in the Workplace, 2017), with three targeting the mental well-being of employees with mental ill health (Mood Disorders Society of Canada, 2014; Rethink, 2009; WorkCover SA, 2012). Thematic analysis results involving the cases are provided in Table 1, which includes all themes, coding rules to advance the transparency and reliability of results, along with supporting quotes. These themes consist of policy/procedures; education; legal; leadership; and monitoring/support. After applying the inclusion criterion to the 103 possibly relevant documents as identified from the Google Scholar search, eight journal articles were accepted (Butterworth et al., 2016; Fevre et al., 2013; Karatuna, 2015; Mulder, Pouwelse, Lodewijkx, Bos, & Dam, 2016; Palmer & Ross, 2014; Shallcross, Ramsay, & Barker, 2013; Vickers, 2014; Worth & Squelch, 2015). Grey literature retrieved from the Internet search and those meeting inclusion criterion, thereby critically contributing to theme discussion included three news articles, one public paper and a ‘JobWatch’ submission to the Parliament of Victoria’s Inquiry into Workforce Participation by People with Mental Illness (Beecher, 2003; Bevan, 2016; Breden, 2014; Bytheway et al., 2012; Vidot, 2014). Data (i.e., 58 South Asian Journal of Business and Management Cases 9(1) Table 1. Case Study Coding Results Theme Coding Rule Policy Policy/procedures to help prevent/address the bullying of employees (including those with mental illness). Education Legal Exemplary Quotes ‘a policy related to harassment and bullying (or include this in an OHS or equity policy)’. (AHRC, 2010, p. 24) ‘Implement anti-bullying and workplace harassment policies and have conflict resolution practices in place’. (CCS, 2012) ‘Organizations must implement policies and practices that promote and protect employee mental health and psychological safety’. (CMHA, 2018, p. 34) ‘Policies exist for psychological protection – anti-retaliation, anti-bullying, and anti-harassment’. (Mood Disorders Society of Canada, 2014, p. 37) ‘Ensure that work policies stress zero tolerance to bullying and harassment in the workplace’. (WorkCover SA, 2012, p. 9) ‘In developing a policy to prevent harassment or bullying, the focus needs to be on preventing and responding to behaviours that are offensive or potentially harmful to others’. (GreatWest Life Centre for Mental Health in the Workplace, 2017) Educate staff to help prevent/ ‘Develop greater understanding through education and address the bullying of employees training’; ‘mental health awareness training’; ‘bullying and (including those with mental harassment’; ‘diversity and disability awareness training’. illness). (AHRC, 2010, p. 25) ‘Create awareness of what bullying is, how to address bullying behaviours and how to report bullying’. (AHS, 2014, pp. 17–18) ‘Provide conflict resolution and emotional intelligence training for all managers that specifically considers employee mental health concerns’. (Great-West Life Centre for Mental Health in the Workplace, 2017) ‘Ensure that work policies stress zero tolerance to bullying and harassment in the workplace and that the consequences of that behaviour are clearly explained’. (WorkCover SA, 2012, p. 9) ‘It is the legal duty of an employer to protect the mental and Legal instruments to help physical health of employees.’ ‘That means protection from prevent/address the bullying of harassment, violence, and bullying’. (CMHA, 2018, p. 33) employees (including those with mental illness). ‘Essentially, new legal standards are not permitting conduct that would have been tolerated less than a decade ago’. (CMHA, 2018, p. 57, citing Guarding Minds@Work, 2009) ‘Legal review of the policy, if appropriate’. (Great-West Life Centre for Mental Health in the Workplace, 2017) ‘the law (Disability Discrimination Act 1995) says that people with disabilities must not be at a disadvantage in the workplace, or when looking for work’. (Rethink, 2009, p. 5) ‘there are legal risks for employers who neglect the psychological well-being of their employees’. (Mood Disorders Society of Canada, 2014, p. 32) (Table 1 continued) 59 Mellifont (Table 1 continued) Theme Coding Rule Exemplary Quotes Leadership Leaders to help prevent/address the bullying of employees (including those with mental illness). Monitoring/ Support Monitoring/support activities to help prevent/address the bullying of employees (including those with mental illness). ‘The individual needs to be able to trust that their manager, and their colleagues, will not let them down by treating them badly if they disclose or have adjustments provided’. (Rethink, 2009, p. 18) ‘setting an expectation that all employees and leadership interact in ways that are calm, mindful of one another’s contributions and opinions and which promote dialogue among team members’. (Mood Disorders Society of Canada, 2014, p. 43) ‘This document aims to help leaders create and maintain a psychologically safe workplace’. (AHS, 2014, p. 3) ‘include a statement from top management to all workers stating that bullying is inappropriate and will not be tolerated’. (CMHA, 2018, p. 34 citing Government of Western Australia, 2006) ‘Leadership development should integrate bullying and harassment prevention’. (Great-West Life Centre for Mental Health in the Workplace, 2017) ‘Check in with staff at monthly team meetings to ensure that no bullying behaviours are displayed and that people are treating each other with respect’. (AHS, 2014, p. 18) ‘clearly state that retaliation against or victimization of workers who report workplace bullying will not be tolerated’. (CMHA, 2018, p. 35) ‘Support from Human Resources to manage problematic relationships at work, or bullying, should also be provided’. (Rethink, 2009, p. 28) Source: The author. quotes and paraphrases) as derived from these scholarly and grey literature sourced texts are referenced in the next section under the respective theme headings to which they speak. Discussion Policy and Procedures Anti-bullying policy is endorsed within specialized mental health promotion guides (Mood Disorders Society of Canada, 2014; WorkCover SA, 2012) and also among generic guides (AHRC, 2010; CCS, 2012; CMHA, 2018; Great-West Life Centre for Mental Health in the Workplace, 2017). Support for anti-bullying policy is further available from the grey literature. To this end, Bytheway et al. (2012) suggested that considering staff health implications along with potential economic costs, it is fitting for employers to develop and deliver bullying prevention and treatment policy together with complaint procedures. However, the design and implementation of such policy is no guarantee of success. Scholarly literature draws attention to challenges that hold potential to undermine the effectiveness of the 60 South Asian Journal of Business and Management Cases 9(1) anti-bullying policy of which developers should be aware. For instance, while it is posited that antibullying policies send a message that this activity will be promptly tackled (Mood Disorders Society of Canada, 2014), fair and unbiased assessments of bullying claims should not be presumed. Butterworth et al. (2016, p. 1093) make the point, ‘there is little incentive to report workplace bullying when there is no clear pathway to resolve disputes and those who report bullying risk further victimization and loss of career opportunities.’ Vickers (2014, p. 108) also comments, ‘any failure to protect the health and wellbeing of targeted employees, by bullies, or by any worker charged with protecting them, such as line- or HR-managers, is not just poor management, but corruption.’ The personal impacts following such corrupt behaviour can be considerable. When targets make formal grievances and have management undervalue these complaints or side with the bully, these persons can end up resigning (Karatuna, 2015). These kinds of procedural failures hold particular implications for diversity promotion policies, endeavouring to increase the representation of a staff with disabilities (including persons who identify as neurodiverse). In this regard, corrupted bullying reporting and assessment procedures might allow supervisors and HR managers to ‘move on’ mentally diverse individuals. Interference in bullying claim processes can originate from a variety of sources. Vickers (2014) warns that bullies can attempt to influence process results. Moreover, relief from bullying cannot be assumed to come from consultants who are charged to ‘independently’ assess allegations. According to Shallcross, Ramsay, and Barker (2013), consultants might hold a biased interest in attaining organizational results so as to attain future contracts. Following on, the reach of mobbing should not be underestimated as potential exists for this inappropriate behaviour to infiltrate the bullying investigations themselves. Workplace anti-bully policy should, therefore, endorse independent audits of unsuccessful claims as lodged by staff (including those who are neurodiverse). Importantly, these audits should be regularly conducted by professionals who do not hold comfortable contractual relationships with employers. Education Education is another area where concentrated efforts are needed to help redress the bullying of neuro­ diverse employees. This measure is again recognized across specialized and generic mental health promotion guides (AHRC, 2010; AHS, 2014; Great-West Life Centre for Mental Health in the Workplace, 2017; WorkCover SA, 2012). Support for greater neurodiversity awareness can be found in the scholarly literature. Underlying a need to confront popular misconceptions about mental disorders, Palmer and Ross (2014, p. 29) noted, ‘most historical portrayals of mental patients reinforce public perceptions of the mentally ill as needing a different order of control and treatment than is required for any other type of illness or behaviour.’ For HR practitioners, supervisors and other staff whose perceptions about mental diversity and bullying behaviours are compatible with these negative depictions, workplaces might assist in availing alternate and accurate information. Education may also target mobbing behaviour. Mulder et al. (2016, p. 216) suggested, ‘workplace mobbing interventions should not only focus on victims and perpetrators but on bystanders as well, for instance, through workshops, cultural change programmes, coaching and performance appraisal interviews.’ Anti-mobbing education can thus be said to hold broad audience reach and delivery mechanism potential. Targeted education is also required around the topic of accommodating neurodiversity in the work­place. Such accommodations are reasonable where they assist the employee and are not excessive in terms of cost, disturbance or impracticality (Rethink, 2009). Nevertheless, grey literature and scholarly literature alike recognize that even where deemed reasonable, the receipt of reasonable accommodations by neurodiverse employees can be accompanied by harassment. Beecher (2003) cautions colleagues might rapidly become Mellifont 61 weary of staff with mental ill health receiving special conditions. Moreover, mistreatment around these adjustments can include public shaming and highlighting a need for special conditions (Fevre et al., 2013 citing Foster, 2007). Also related to mental diversity accommodation requests and possible risks of bullying is the organizational concept of resilience. Resiliency is a mechanism of recovering from challenging experiences and developing individual strengths (AHS, 2014). Nonetheless, Bevan (2016, p. 15) notes, ‘if resilience interventions comprise only ‘sheep dip’ training workshops for as many employees as possible in the hope that they will be inoculated from badly designed jobs, bullying cultures, and empathy-free managers, then I think we may have a problem.’ Following on, mentally diverse employees who need reasonable accommodations should not be advised by armchair psychiatrists that they need to toughen up, be resilient and carry on as ‘normal’. When it comes to neurodiverse staff accessing reasonable accommodations to which they might desire, organizational concepts such as resilience should not be rolled out by HR practitioners or supervisors in attempts to excuse bad decisions or bullying behaviours. Education is needed to help advance understanding about neurodiversity in the workplace and subsequent reasonable adjustments that some mentally diverse employees might require. Legal Broad support for legal protection against bullying can be found within specialized and generic mental health promotion guides (CMHA, 2018; Great-West Life Centre for Mental Health in the Workplace, 2017; Mood Disorders Society of Canada, 2014; Rethink, 2009). From this perspective, it is not enough for workplaces to consider only the physical health of staff. Across a multitude of jurisdictions, an obligation exists for employers to safeguard both the physical and mental well-being of employees (Great-West Life Centre for Mental Health in the Workplace, 2017). Anti-bullying legislation is producing practical results. For instance, in Canada, case law has deemed employers accountable for exposing staff to dangerous settings that have brought about psychological damage (CMHA, 2018). Guarding Minds@ Work (2009) and CMHA (2018) see contemporary legal requirements as prohibiting behaviour that would have been allowed fewer than 10 years earlier. An important qualifier on this progress is that while certain jurisdictions are taking workplace bullies to task through the use of legislation, the implementation of this policy instrument is far from universal. Legislation positioning employers as being more accountable for employees’ physical and psychological well-being is thus depicted as ‘evolving’ (CMHA, 2018, p. 57). Support for the legal anti-bullying measure as an instrument for protecting staff (including those who identify as mentally diverse) from bullying can be found within the grey literature. Breden (2014) elaborates that in Australia, anti-bully law as introduced in 2014, enables employees to issue claims of alleged bullying via the Fair Work Commission. However, scholarly literature also recognizes that even where laws, which endeavour to protect the rights of vulnerable employees, are in place, there is no guarantee that these laws will be utilized. To this end, Worth and Squelch (2015, p. 1028) state, ‘the risk of under-utilization of the anti-bullying jurisdiction by those for whom it was designed to help has therefore been recognized.’ Future research is needed to reveal the barriers confronting a greater use of anti-bullying legislation by employees, and in particular by staff who are neurodiverse, along with the roles of policymakers and practitioners in redressing this situation. Leadership Specialized guides and guides catering to mental health promotion for staff (including neurodiverse employees) position leadership as an effective anti-bullying measure (AHS, 2014; CMHA, 2018; 62 South Asian Journal of Business and Management Cases 9(1) Great-West Life Centre for Mental Health in the Workplace, 2017; Mood Disorders Society of Canada, 2014; Rethink, 2009). Indeed, leaders have a role to play in creating and sustaining a mentally safe work environment (AHS, 2014). However, guides also warn of the potential for poor management to contribute to workplace bullying. In this regard, controlling leaders and ones who seldom provide feedback raises the prospect of workplace bullying (Great-West Life Centre for Mental Health in the Workplace, 2017). The Mayo Clinic (2008) and CMHA (2018) also recognized micromanaging as a trigger for employee burnout. Rather than improving work environments, the opposite can be said of these controlling behaviours. Importantly, while workplace leaders should avoid partaking in bullying activity, neurodiverse managers themselves are not immune from mistreatment in the workplace. In this context, Bevan (2016, p. 15) explains, ‘senior managers are far less likely to disclose any lived experience of mental illness— even in their families—for fear of this damaging their prospects for advancement or their internal and external reputations for toughness.’ Managers (and others) who identify with neurodiversity should thus be educated about their legal rights not to be bullied following their disclosure. In doing so, possible synergies between anti-bullying measures (education, legal and leadership in this instance) might be advanced. Perhaps one indicator as to how inclusive a workplace culture is in terms of embracing neurodiversity is the extent to which organizational leaders (including HR managers) are able to disclose their mental diversity without experiencing mistreatment and exclusion from future career development opportunities. Monitoring and Support Anti-bullying monitoring and support activities are endorsed among specialized and generic guides seeking to advance mental health in the workplace (AHS, 2014; CMHA, 2018; Rethink, 2009). This measure has implications across areas of employee selection and retention. Holding relevance to inclusive recruitment processes, the Great-West Life Centre for Mental Health in the Workplace (2017) guide calls for employers to be diversity conscious so as to avert exclusion, particularly around mental health issues. Where diversity is shunned in selection procedures, possibilities abound for neurodiverse candidates to experience bullying. Illustrating this point, Bevan (2016) describes an HR director whose goal was to construct a psychometric tool that could weed out non-resilient candidates for positions. Following on, biased selection panels who might equate mental diversity with poor resilience may apply such a tool to test for signs of psychiatric conditions. Consequently, neurodiverse persons might be bullied out of positions that they rightfully deserve on occasions where invasive psychometric analysis returns a particular likelihood of them being non-neurotypical. Prospective employees with neurodiversity or suspected of being neurodiverse might, therefore, find themselves as targets for workplace bullies. A need thus exists to develop monitoring mechanisms that are sophisticated enough to identify technologically assisted forms of bullying in candidate assessment procedures. Detection and treatment of bullying behaviour are also required in efforts to help retain mentally diverse employees. Vidot (2014) explains that some of these persons can feel team problems being attributed to their conditions. Moreover, linking back to the leadership theme, Bytheway et al. (2012, p. 14) indicate that ‘organizational culture/climate surveys and grievance proceedings can provide evidence of problems caused by particular managers and management styles’. However, heeding the aforementioned Vicker’s (2014) warning about the potential for corruption, it is possible that evidence gained from staff surveys suggesting that some neurodiverse employees are being bullied might be overlooked in unprincipled efforts to protect intolerant supervisors. Hence, the point is made that the availability of workplace anti-bullying monitoring mechanisms alone is not enough. For workplaces to demonstrate in a practical way that they are genuine about identifying and addressing the mistreatment Mellifont 63 of staff (including those who are neurodiverse), a requirement also exists to objectively observe behaviour across all levels of the organization. Crucially, where bullying is detected, HR assistance should be availed (Rethink, 2009). Neurodiversity Anti-bullying Advancement from a Social Cognitive Theory Perspective Social cognitive theory (SCT) highlights the part played by cognitions in shaping the behaviour of individuals (Swearer, Wang, Berry, & Myers, 2014 citing Bandura, 1986). In line with SCT, persons are inclined to shun behaviours to which they perceive their involvement will be penalized and participate in those to which they see as being rewarded (Swearer et al., 2014 citing Bandura, 1977). This theory holds practical relevance in terms of implementing each of the neurodiversity anti-bullying themes as revealed by this investigative study. While ‘carrots’ (i.e., rewards) should be used at every opportunity to help avoid the bullying of neurodiverse employees in the first instance, when such behaviour occurs or is popularly repeated (as within toxic workplace cultures), ethical organizations should not hesitate to apply the ‘stick’ of sanctions. Taking care to ensure that once identified, workplace bullies do not themselves become bullied, penalties can take on many forms. Commencing with anti-bullying policy, grievance assessment officers need to be aware of the risks to their professional reputations should independent audits reveal that they have participated in the mobbing of neurodiverse claimants. Similarly, the staff at any level of an organization who penalize mentally diverse staff for exercising their legal rights should be made aware that such behaviour is unethical and will not be tolerated. Education about neurodiversity in the workplace should be mandatory and management should formally call upon those refusing to attend informational sessions to explain their tardiness. Neurodiverse leaders and others need to feel confident that disclosure of their mental diversity in the workplace will be respected and that people will be held accountable for any conduct to the contrary. Further, investment in independent research is needed to expose organizations who bully existing or prospective staff out of career advancement opportunities as warranted by their abilities. However, it is reasonable to suggest that organizations who fail to value neurodiversity will be unlikely to welcome such research. This article poses the following two key questions for readers to consider in relation to this previous point: (a) are you aware of any organization (s) that would likely hold a poor attitude towards the prospects of having independent research critically examine their performance in relation to neurodiversity employment? and (b) for any organization (s) identified above, what rewards and/or penalties do you think might encourage a change in this attitude? Limitations This exploratory study has notable limitations to which the author openly acknowledges. These include the anti-bullying themes being informed by a small sample of mental health promotion guides. Evidence from scholarly and grey literature was also purposefully confined to critically reviewing these themes. It is, therefore, possible that broadened database searches and inclusion criteria as undertaken in any future studies might identify themes and accompanying challenges that are not covered within the scope of this investigative research. Hence, themes, as discussed in this article along with their critical assessments, should not be considered as necessarily being comprehensive. Investment in future research is needed to test and potentially expand upon these preliminary findings. 64 South Asian Journal of Business and Management Cases 9(1) Conclusion What capacity do mental health promotion guides have to help prevent or treat the bullying of neurodiverse employees? This study reveals three key messages that should be of interest to policymakers and practitioners working in the Asia-Pacific region and elsewhere. First, specialized and generic mental health promotion guides as reviewed by this study collectively support anti-bullying themes across dimensions of policy/procedures, education, legal, leadership and monitoring/support. Second, evidence sourced from scholarly and grey literature raise challenges that if overlooked might reduce the effectiveness of guide endorsed anti-bullying measures to support mentally diverse employees on occasions where such assistance is needed. These include potential risks as follows: corrupted bullying reporting and assessment procedures undermining diversity promotion policy; ignorance around a possible need for personalized accommodations and neurodiversity more generally; underutilization of the legal policy instrument; leaders (and others) experiencing mistreatment upon disclosure of their neurodiversity; and monitoring mechanisms failing to detect neurodiversity targeted bullying behaviours throughout phases of employment selection and retainment. Finally, this study raises the prospect that anti-bullying measures to assist neurodiverse staff might be more effective when potential synergies between these are recognized and encouraged. HR practitioners, counsellors and managers might, therefore, find themselves drawing upon suites of measures in order to help prevent and treat the bullying of employees who identify as neurodiverse. Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article. Funding The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article. References Alberta Health Services (AHS). (2014). Making Alberta Health Services (AHS) a psychologically safe workplace: A toolkit for managers. Retrieved from http://events.nupge.ca/sites/default/files/documents/ptsd/hr-waspsychological-safety-toolkit.pdf Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC). (2010). Workers with mental illness: A practical guide for managers. Sydney, Australia: Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC). Retrieved from https://www.humanrights. gov.au/our-work/disability-rights/publications/2010-workers-mental-illness-practical-guide-managers Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Oxford, England: Prentice-Hall. ———. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: PrenticeHall. Beecher, G. (2003). Dealing with mental illness in the workplace. Retrieved from http://www.tved.net.au/index. cfm?SimpleDisplay=PaperDisplay.cfm&PaperDisplay=http://www.tved.net.au/PublicPapers/October_2003,_ Lawyers_Education_Channel,_Dealing_with_Mental_Illness_in_the_Workplace.html Bevan, S. (2016). Solitary journey. Occupational Health & Wellbeing, 68(8), 14–15. Boccio, D., & Macari, A. (2014). Workplace as a safe haven: How managers can mitigate risk for employee suicide. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 29(1), 32–54. Bond, S., Tuckey, M., & Dollard, M. (2010). Psychosocial safety climate, workplace bullying, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress. Organization Development Journal, 28(1), 37–56. Branch, S., Ramsay, S., & Barker, M. (2013). Workplace bullying, mobbing and general harassment: A review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(3), 280–299. Mellifont 65 Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. Breden, R. (2014). Lessons learnt from the ashes. EnableHR. Retrieved from http://news.enablehr.com.au/lessonslearnt-from-the-ashes Broomhall, T. (2013). Mental illness in the workplace. Blooming Minds. Retrieved from https:// bloomingminds. com.au/mental-illness-in-the-workplace/ Butterworth, P., Leach, L., & Kiely, K. (2016). Why it’s important for it to stop: Examining the mental health correlates of bullying and ill-treatment at work in a cohort study. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 50(11), 1085–1095. Bytheway, Z., Warner, F., & Cotchin, G. (2012). Inquiry into workforce participation by people with a mental illness. Melbourne, Australia: JobWatch. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/file_uploads/ Mental_Health_Report_FCDC_1cX3KrFw.pdf Canadian Cancer Society (CCS). (2012). Healthy minds module: Support tools. Toronto, Canada: Canadian Cancer Society (CCS). Retrieved from http://www.cancer.ca/en/prevention-and-screening/reduce-cancer-risk/helpfultools/?region=on Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA). (2018). Workplace mental health promotion: A how-to guide. Canadian Mental Health Association [CMHA] and University of Toronto. Retrieved from http://wmhp. cmhaontario.ca/ wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/WMHP-Guide-Final1.pdf Carter, M., Thompson, N., Crampton, P., Morrow, G., Burford, B., Gray, C., & Illing, J. (2013). Workplace bullying in the UK NHS: A questionnaire and interview study on prevalence, impact, and barriers to reporting. BMJ Open, 3(6), 1–12. Devonish, D. (2017). Dangers of workplace bullying: Evidence from the Caribbean. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 9(1), 69–80. Dhar, R. (2012). Why do they bully? Bullying behavior and its implication on the bullied. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 27(2), 79–99. Dollard, M., Bailey, T., McLinton, S., Richards, P., McTernan, W., Taylor, A., & Bond, S. (2012). The Australian workplace barometer: Report on psychosocial safety climate and worker health in Australia. Canberra, Australia: Safe Work Australia. Retrieved from https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1702/theaustralian-workplace-barometer-report.pdf Einarsen, S. (2000). Harassment and bullying at work: A review of the Scandinavian approach. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 5(4), 379–401. Felson, R. B. (1992). ‘Kick’em when they’re down’: Explanations of the relationships between stress and interpersonal aggression and violence. The Sociological Quarterly, 33(1), 1–16. Fevre, R., Robinson, A., Lewis, D., & Jones, T. (2013). The ill-treatment of employees with disabilities in British workplaces. Work, Employment and Society, 27(2), 288–307. Foster, D. (2007). Legal obligation or personal lottery? Employee experiences of disability and the negotiation of adjustments in the public sector workplace. Work, Employment & Society, 21(1), 67–84. Francioli, L., Hogh, A., Conway, M., Costa, G., Karasek, R., & Hansen, A. (2016). Do personal dispositions affect the relationship between psychosocial working conditions and workplace bullying? Ethics & Behavior, 26(6), 451–469. Glambek, M., Skogstad, A., & Einarsen, S. (2016). Do the bullies survive? A five-year, three-wave prospective study of indicators of expulsion in working life among perpetrators of workplace bullying. Industrial Health, 54(1), 68–73. Glaso, L., Nielsen, M., & Einarsen, S. (2009). Interpersonal problems among perpetrators and targets of workplace bullying. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(6), 1316–1333. Government of Western Australia. (2006). Bullying in the workplace. Retrieved from www.commerce.wa.gov.au/ worksafe/PDF/Codes_of_Practice/Code_violence.pdf Great-West Life Centre for Mental Health in the Workplace. (2017). Harassment and bullying prevention. Retrieved from https://www.workplacestrategiesformentalhealth.com/job-specific-strategies/harassment-and-bullyingprevention 66 South Asian Journal of Business and Management Cases 9(1) Guarding Minds@Work. (2009). The legal & regulatory case for psychological safety & health. Retrieved from http:// www.guardingmindsatwork.ca/docs/The%20Legal%20Regulatory%20Case%20for%20Psychological%20 Safety%20Health.pdf Harrington, S., Rayner, C., & Warren, S. (2012). Too hot to handle? Trust and human resource practitioners’ implementation of anti-bullying policy. Human Resource Management Journal, 22(4), 392–408. Howard, J., Johnston, A., Wech, B., & Stout, J. (2016). Aggression and bullying in the workplace: It’s the position of the perpetrator that influences employees’ reactions and sanctioning ratings. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 28(2), 79–100. Karatuna, I. (2015). Targets’ coping with workplace bullying: A qualitative study. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 10(1), 21–37. Leach, L., Poyser, C., & Butterworth, P. (2016). Workplace bullying and the association with suicidal ideation/ thoughts and behaviour: A systematic review. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 74(1), 1–8. Lee, R. T., & Brotheridge, C. M. (2006). When prey turns predatory: Workplace bullying as a predictor of counteraggression/bullying, coping, and well-being. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15(3), 352–377. Lutgen-Sandvik, P. (2008). Intensive remedial identity work: Responses to workplace bullying trauma and stigmatization. Organization, 15(1), 97–119. Mayo Clinic. (2008). Job burnout: Understand symptoms and take action. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic. org/healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/in-depth/burnout/art-20046642 Meglich-Sespico, P., Faley, R., & Knapp, D. (2007). Relief and redress for targets of workplace bullying. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 19(1), 31–43. Mood Disorders Society of Canada. (2014). Workplace mental health: How employers can create mentally healthy workplaces and support employees in their recovery from mental illness. Retrieved from http://mdsc.ca/docs/ Workplace_Mental_Health.pdf Mulder, R., Pouwelse, M., Lodewijkx, H., Bos, A., & Dam, K. (2016). Predictors of antisocial and prosocial behaviour of bystanders in workplace mobbing. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 26(3), 207–220. Nielsen, M., & Knardahl, S. (2015). Is workplace bullying related to the personality traits of victims? A two-year prospective study. Work & Stress, 29(2), 128–149. Nielsen, M., Matthiesen, S., & Einarsen, S. (2010). The impact of methodological moderators on prevalence rates of workplace bullying: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(4), 955–979. O’Driscoll, M. P., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Bentley, T., Catley, B. E., Gardner, D. H., & Trenberth, L. (2011). Workplace bullying in New Zealand: A survey of employee perceptions and attitudes. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 49(4), 390–408. O’Rourke, A., & Antioch, S. (2016). Workplace bullying laws in Australia: Placebo or panacea? Common Law World Review, 45(1), 3–26. Palmer, M., & Ross, D. (2014). Tracing the maddening effects of abuses of authority: Rationalities gone violent in mental health services and universities. Social Alternatives, 33(3), 28. Paterson, T. (2011). Disenfranchised workers: A view from within the public service. Retrieved from http://vuir. vu.edu.au/21317/1/Tanya_Jane_Paterson.pdf Rethink. (2009). We can work it out: A local authority line manager’s guide to reasonable adjustments for mental illness. Retrieved from https://torch.taw.org.uk/Corporate Information/OccupationalHealth/Shared%20 Documents/Managers%20Guide.pdf Salin, D. (2008). The prevention of workplace bullying as a question of human resource management: Measures adopted and underlying organizational factors. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 24(3), 221–231. Samnani, A., & Singh, P. (2014). Performance-enhancing compensation practices and employee productivity: The role of workplace bullying. Human Resource Management Review, 24(1), 5–16. Shallcross, L., Ramsay, S., & Barker, M. (2013). Severe workplace conflict: The experience of mobbing. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 6(3), 191–213. Mellifont 67 Swearer, S. M., Wang, C., Berry, B., & Myers, Z. R. (2014). Reducing bullying: Application of social cognitive theory. Theory into Practice, 53(4), 271–277. Tehrani, N. (2004). Bullying: A source of chronic posttraumatic stress? British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 32(3), 357–366. Ternan, W., Dollard, M., & LaMontagne, A. (2013). Depression in the workplace: An economic cost analysis of depression-related productivity loss attributable to job strain and bullying. Work & Stress, 27(4), 321–338. Venettoklis, T., & Kettunen, P. (2016). Workplace bullying in the Finnish public sector: Who, me? Review of Public Personnel Administration, 36(4), 370–395. Vickers, M. (2014). Towards reducing the harm: Workplace bullying as workplace corruption: A critical review. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 26(2), 95–113. ———. (2015). Telling tales to share multiple truths: Disability and workplace bullying: A semi-fiction case study. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 27(1), 27–45. Vidot, A. (2014). Employees with mental illness still report stigma in the workplace. Retrieved from http://www.abc. net.au/worldtoday/content/2014/s4102741.htm WorkCover SA. (2012). Managing psychological injuries: A guide for rehabilitation and return to work coordinators. Adelaide, Australia: WorkCover SA. Workplace Bullying Institute. (2010). Results of the 2010 and 2007 WBI U.S. Workplace bullying survey. Retrieved from http://www.workplacebullying.org/wbiresearch/2010-wbi-national-survey/ Worth, R., & Squelch, J. (2015). Stop the bullying: The anti-bullying provisions in the Fair Work Act and restoring the employment relationship. UNSW Law Journal, 38(3), 1015–1045. Wu, S. H., & Wu, C. C. (2018). Bullying bystander reactions: A case study in the Taiwanese workplace. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources. doi:10.1111/1744-7941.12175. Yin, R. (2004). Case study methods: Revised draft. Retrieved from http://www.cosmoscorp. com/docs/ aeradraft.pdf