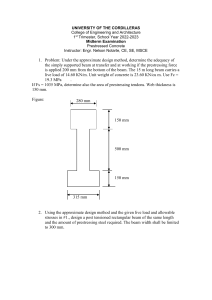

ACI 372R-00: Prestressed Concrete Structure Design & Construction

advertisement