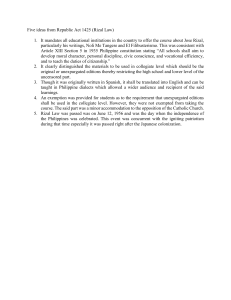

HOW A BILL BECOMES A LAW THE TRIALS OF THE RIZAL BILL The Trials of The Rizal Bill (Author: Jose B. Laurel, Jr) REPUBLIC ACT NO. 1425 “AN ACT TO INCLUDE IN THE CURRICULA OF ALL PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SCHOOLS, COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES COURSES ON THE LIFE, WORKS, AND WRITINGS OF JOSE RIZAL, PARTICULARLY HIS NOVELS NOLI ME TANGERE AND EL FILIBUSTERISMO, AUTHORIZING THE PRINTING AND DISTRIBUTION THEREOF, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES.” Approved: June 12, 1956 Published in the Official Gazette, Vol. 52, No. 6, p. 2971 in June 1956. Because of that law, “Rizal” is a required subject in most colleges in the Philippines. Let Us Now Find Out How Rizal Bill Becomes A Law APRIL 3, 1956 Senate Bill No. 438 In 1956, Senator Claro M. Recto filed a measure that became the original RIZAL Bill recognizing the need to instill heroism among the youth at the time when the country was experiencing social turmoil. The original version reads as follows: "AN ACT TO MAKE NOLI ME TANGERE AND EL FILIBUSTERISMO COMPULSORY READING MATTERS IN ALL PUBLIC AND PRIVATE COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES." APRIL 17, 1956 Senator Jose P. Laurel, as Chairman of the Committee on Education, began his sponsorship of the measure and began delivering speeches for the proposed legislation. "The objective of the measure was to disseminate the ideas and ideals of the great Filipino patriot through the reading of his work, particularly Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo" APRIL 19, 1956 House Bill No. 5561 Jacobo Gonzales "An Act to Include in the Curricula of All Public and Private Schools, Colleges and Universities courses on the Life Works and Writings of JOSE RIZAL, particularly his novels NOLI ME TANGERE and EL FILIBUSTERISMO, Authorizing the Printing and Distribution Thereof, and for Other Purposes." The time when the conflict reached the House of Representatives. The Bill is identical copy of Senate Bill No. 438. APRIL 23,1956 Debates in Senate Bill begun Senator Mariano J. Cuenco, Francisco Rodrigo and Decoroso Rosales are identified as rabid Catholics opposed the said Bill. The Catholic church claimed that the two novels contained news inimical to the tenet of their faith and includes the violation of religious freedom. "Let us not create a conflict between nationalism and religion; between the government and the church." Rodrigo said. But, Senator Recto claimed that the sole objective of the bill was to foster the better appreciation of Rizal's times and of the role he played in combating Spanish tyranny in this country. The Catholic Church Against Rizal Law and Senator Claro M. Recto • When the Catholic Church in the Philippines found out about Recto’s bill, it mobilized its forces to prevent the bill from becoming law. • Ironically, almost 70 years after the publication of Noli Me Tangere, the Church still viewed Rizal’s novels as blasphemous. • The Catholic Church of 120 years ago used the same influence in preventing the novels to be read by Filipinos. • No less than Manila Archbishop Rufino Santos penned an impassioned pastoral letter protesting the bill. It was read in all masses in the country, much to the ire of then Manila Mayor Arsenio Lacson, who allegedly walked out of the mass when he heard the pastoral letter being read. Lacson was one of the most vocal supporters of the Rizal Bill. • In his pastoral letter, Archbishop Santos argued that the compulsory reading of the original versions of Rizal’s novels would negatively affect students. • Those who opposed the Rizal Bill painted Recto as communist and anti-Catholic. • According to Abinales and Amoroso (2005), the Church feared the bill would violate freedom of conscience and religion. • A coalescence of religious groups within the church rallied to block the passage of the bill in the Senate. • Among the most active groups that opposed the Rizal Bill were the Catholic Action of the Philippines, the Knights of Columbus, the Congregation of the Mission, and the Catholic Teachers Guild. • The Catholic Church urged its faithful to write to lawmakers to make their opposition to the bill known. Catholic groups organized symposiums on why it should not become law. • In one of these symposiums, Fr. Jesus Cavanna allegedly argued the novels would misrepresent current conditions in the church. Cavanna was the author of the book, Rizal's Unfading Glory: A Documentary History of the Conversion of Dr. José Rizal, published in 1956 after the passage of the Rizal Law. The book details Jose Rizal’s conversion to Catholicism. • Several Catholic schools around the country banded together in opposition to the Rizal Bill. It came to a point when a number of Catholic schools threatened to close down if the Rizal Bill became law. • Senator Recto responded by saying the government would simply take over the administration of these schools if they closed, and nationalize them. •“The people who would eliminate the books of Rizal from the schools would blot out from our minds the memory of the national hero. This is not a fight against Recto but a fight against Rizal,” Recto said. MAY 2, 1956 Report of Committee on Education, recommending approval without amendment. MAY 9, 1956 Debate about the amendment of original bill started • Notable Defenders: Congressmen Emilio Cortez, Mario Bengzon, Joaquin R. Roces, W. Rancap Lagumbay • Outspoken Opponents: Congressmen Ramon Durano, Jose Nuguid, Marciano Lim, Manuel Zosa, Lucas Paredes, Godofredo Ramos, Miguel Cuenco and Congresswomen Carmen D. Consing and Tecla San Andres Ziga • As the daily debates wore in Congress and throughout the country, it become more apparent that no agreement could be reached on the original version of the Bill. • However, Senator Laurel, sensing the futility of further strife on the matter, rose to propose in his own name an amendment by substitution. MAY 12, 1956 Senator Lim, proposed the exemption of students from the requirements of the bill. The amendment to the amendment state: "The Board shall promulgate rules and regulations providing for the exemption of students for reason of religious belief stated in a sworn written statement from the requirement of the provision contained in the second part of the first paragraph of this section; but not from taking the course provided for in the first part of said paragraph.“ The amendment is unanimously approved. The second reading also approved unanimously. • Congressman Arturo M. Tolentino, the brilliant House Majority Floor Leader, sponsored the amendment by substitution identical to Senator Laurel's substitute bill as amended and approved on second reading in the Upper House. • Congressman Miguel Cuenco - "measure was unconstitutional" • Congressman Bengzon - "The substitute bill represented a complete triumph of the Church Hierarchy" • No less than 51 congressman appearing as its co-authors, including the majority and minority leadership in the Chamber. May 17, 1956 Congress was to adjourn since it would due in few days, the President (Ramon Magsaysay) had declined to certify to the necessity of the immediate enactment of measure. There is need of complying with the constitutional requirement that printed copies thereof be distributed among the Congressmen at least three calendar day prior to its final approval by the House. 1. Senate Bill No. 438 was approved in third reading with 23 votes in favor. 2. House Bill No. 5561 was also approved on third reading with 27 votes in favor (6 were against, 2 abstained and 17 were absent). 3. This bill was passed by the latter Chamber without amendment. 4. Provided that the number of the Senate bill should appear in enrolled courses. On June 12, President Ramon Magsaysay signed the bill as Republic Act 1425. More than 50 years after the “Rizal Law”, Catholic Ateneo de Manila is at the forefront of Rizal studies, especially with fellow columnist and Rizalist Ambeth Ocampo teaching there. Ateneo’s main library is named after Rizal. This fulfilled the words of Rizal who through Pilosofo Tasio in Noli Me Tangere, said: "I am writing for the generations of Filipinos yet to come, a generation that will be enlightened and educated, a generation that will read my books and appreciate them without condemning me as a heretic." PRES. RAMON MAGSAYSAY - a Filipino statesman who served as the 7th President of the Philippines, from December 30, 1953 until his death in an aircraft disaster. On December 26, 1994, In the preparation for the centennial commemoration of Dr. Jose Rizal's martyrdom, President Fidel V. Ramos issued Memorandum Order No. 247, directing the Secretary of the Department of Higher Education, Culture and Sport (DECS) and the Chairman of the Commission on Higher Education (CHED) to take steps to fully implement to the letter the intent and spirit of R.A. 1425, popularly known as Rizal Law. THE RIZAL LAW AND THE CATHOLIC HIERARCHY, IN THE MAKING OF A FILIPINO Claro Mayo Recto (Feb. 8, 1890- Oct. 2, 1960) - The main sponsor and defender of the Rizal Bill Biography Born in Tiaong, Tayabas (Quezon) Parents: Claro Recto, Sr. and Micaela Mayo Completed his primary education in his hometown and his secondary education in Batangas Moved to Manila and completed his AB degree at the Ateneo and was awarded as maxima cum laude in 1909 Finished his law degree in 1914 at UST and was admitted to the BAR that same year Wife: Aurora Reyes, 5 children Political Career - Started as representative of the third district of Batangas. Became the House Minority Floor Leader Elected as a Senator in 1931 In the Senate, he held key positions such as Minority Floor Leader, Majority Floor Leader, and Senate President Pro-Tempore In 1935, he became Associate Justice of the Supreme Court Became an instrument in the drafting of the constitution of the Philippines 1934-35, as he was selected as president of the assembly Served as a diplomat and an important figure in international relations Known as ardent nationalist and man of letters He penned beautiful poetry and prose Died on October 2, 1960 due to heart attack in Italy Recto believed that the reading of Rizal’s Novel would strengthen the Filipinism of the youth and foster patriotism. Thus, making the Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo compulsory reading in all universities and colleges. However, this measure immediately ran into determined opposition from the Catholic hierarchy claiming that this would VIOLATE FREEDOM OF CONSCIENCE AND RELIGION. The Catholic Hierarchy issued a Pastoral Letter, written by Fr. Jesus Cavanna of the Paulist Fathers detailing its objections to the bill and enjoining Catholics to oppose it. ● Francisco Rodrigo proposed for a closed-door conference to search for a solution of the dispute. ● Laurel and its supporters rejected such proposal since public hearing had been made. ● A more organized campaign against the Bill was launched under the Auspices of the Catholic Action of Manila. ● Its first activity was a symposium and open forum in which two announcements are made. The announcements were: 1. That Sentinel (the official organ of the Philippine Catholic Action) would published daily instead of weekly; and 2. That Filipino Catholics would be urged to write to their congressmen and senators asking them to “kill” the Rizal Bill. During the symposium Fr. Jesus Cavanna - Said that the novels of Rizal “belong to the past” and it would be “harmful” to read them because they presented a “false picture” of the conditions in the country at that time. Described Noli Me Tangere as “attack to the clergy” and its object was to “put to ridicule the Catholic Faith” Alleged that the novel was not really patriotic because out of 333 pages only 25 contained patriotic passages while 120 were devoted to anti-Catholic attacks. Radio Commentator Jesus Paredes - “Catholics had the right to refuse to read them so as not to endanger their salvation” Radio Commentator Narciso Pimentel, Jr. - “The bill was Recto’s revenge against Catholic voters who, together with Magsaysay, were responsible for his poor showing in the 1955 senatorial election” RIZAL BILL - Tempers flared during the continuous debates and opponents attacked each other with greater violence. Meanwhile, Bishop Manuel Yap warned the legislators who voted for the Rizal Bill be “punished” in the next election. Recto on the other hand branded him as “the modern-day Torquemada” What does Torquemada mean? Tomás de Torquemada is the first grand inquisitor in Spain, whose name has become synonymous with the Christian Inquisition’s horror, religious bigotry, and cruel fanaticism. • On May 12, the controversy ended with unanimous approval of a substitute measure authored by Sen. Laurel based on the proposals of Sen. Roseller T. Lim and Emmanuel Pelaez • Which accommodated the objections of the Catholic hierarchy, provided that the basic texts in the collegiate courses should be unexpurgated editions of the two novels • Opponents of the original Recto version jubilantly claimed a “Complete Victory” • Proponents felt that they had at least gained something. THE RIZAL BILL OF 1956, HORACIO DE LA COSTA AND THE BISHOPS RA 1425 WITHIN ITS CONTEXT